Builder’s Drawing of Wren and Lark

One item from the Merseyside Maritime Museum exhibition, Ships built in Liverpool for the American Civil War:

Original caption: Curve book, Laird’s Shipyard, Birkenhead showing keel drawings for the blockade runners Lark and Wren, both built by Lairds for the Confederacy. Laird’s built a number of ships for Fraser, Trenhom and the Confederate government, including Lark, Wren, Albatross and Penguin. The Lark and the Wren both left the Mersey in December 1865 1864 and worked in the Gulf of Mexico, running the blockade to ports in Florida and Galveston carrying supplies of clothing, shoes and small arms. On 25 May 1865 the Lark was the last steam blockade runner to enter and leave a Confederate port. (Reference: SAS/25G/1/7)

______

This cross-section is very similar to an earlier Laird-built paddle steamer, Denbigh. Around the outer edge of the hull are notations of plate thicknesses, and the column at right tallies up weights. The spacing of the frames at 21 inches is a bit more than the standard 18 inches, suggesting a willingness to trade structural strength for a saving of weight. We read recently about Wren‘s eventful arrival here in early February 1865; Lark‘s story will be told in due time.

The drawing above, rendered in three dimensions, would be something like this:

__________

Acting Ensign Paul Borner, U.S. Navy

Recently I was able to acquire an original, Civil War-era CDV of a young man named Paul Borner (right). I am not generally a collector of items like this, but there were special circumstances in this case.

Recently I was able to acquire an original, Civil War-era CDV of a young man named Paul Borner (right). I am not generally a collector of items like this, but there were special circumstances in this case.

Borner was a junior naval officer, first an Acting Master’s Mate and then an Acting Ensign, on several U.S. Navy ships on blockade duty during the war. In May 1864, twenty-eight-year-old Borner was put in charge of a boarding party on the captured schooner Sting Ray. What happened next is described in Chapter 3 of the blockade-running book:

A lack of available ships prevented the U.S. Navy from maintaining an around-the-clock watch off the Brazos until the latter part of 1863, but attempts to get in and out of Velasco continued right through the end of the war. One of the more remarkable incidents there occurred in May 1864, when USS Kineo stopped and seized the schooner Sting Ray, nominally of British registry, some miles off the mouth of the river. Kineo’s commander, Lieutenant Commander John Watters, was suspicious of the schooner’s paperwork, which claimed she was sailing from Havana to Matamoros. Not wanting to delay Kineo’s return to the river mouth, Watters put a boarding party on board the schooner, under the command of Acting Ensign Paul Borner, with instructions to follow Kineo back to her station. (more…)

“The Hashish of the West”

John Bull (center) goes shopping for cotton in an 1861 cartoon from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. The proprietor of “Davis & Co.” urges Bull to “break the door open” (i.e., lift the blockade). John Bull declines, saying, “I’ll wait till yer open the door yourself, or that man with the club [the U.S. Navy] opens it for you.” Meanwhile, India (right) is eager to make the sale.

Over at The Atlantic, Sven Beckert has an essay up, based on his book, Empire of Cotton: A Global History. It’s a good read, and well worth your time. Coming as it does on the heels of Edward Baptist’s The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism and Jürgen Osterhammel’s The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century, 2014 seems to be the year when broader studies of cotton, slavery, and their role in the new global economy rose to the forefront.

Southern planters understood that their cotton kingdom rested not only on plentiful land and labor, but also upon their political ability to preserve the institution of slavery and to project it into the new cotton lands of the American West. Continued territorial expansion of slavery was vital to secure both its economic, and even more so its political viability, threatened as never before by an alarmingly sectional Republican Party. Slave owners understood the challenge to their power over human chattel represented by the new party’s project of strengthening the claims of power between the national state and its citizens—an equally necessary condition for its free labor and free soil ideology.

Yet from a global perspective, the outbreak of war between the Confederacy and the Union in April 1861 was a struggle not only over American territorial integrity and the future of its “peculiar institution,” but also over global capitalism’s dependence on slave labor across the world. The Civil War in the United States was an acid test for the entire industrial order: Could it adapt to the even temporary loss of its providential partner—the expansive, slave-powered antebellum United States—before social chaos and economic collapse brought their empire to ruins?

The day of reckoning arrived on April 12, 1861. On that spring day, Confederate troops fired on the federal garrison at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. It was a quintessentially local event, a small crack in the world’s core production and trade system, but the resulting crisis illuminated brilliantly the underlying foundations of the global cotton industry and with it of capitalism.

The outbreak of the Civil War severed in one stroke the global relationships that had underpinned the worldwide web of cotton production and global capitalism since the 1780s. In an effort to force British diplomatic recognition, the Confederate government banned all cotton exports. By the time the Confederacy realized this policy was doomed, a northern blockade effectively kept most cotton from leaving the South. Though smuggling persisted, and most smugglers’ runs succeeded, the blockade’s deterrent effects removed most cotton-carrying ships from the southern trade. Consequently, exports to Europe fell from 3.8 million bales in 1860 to virtually nothing in 1862. The effects of the resulting “cotton famine,” as it came to be known, quickly rippled outward, reshaping industry—and the larger society—in places ranging from Manchester to Alexandria. With only slight hyperbole, the Chamber of Commerce in the Saxon cotton manufacturing city of Chemnitz reported in 1865 that “never in the history of trade have there been such grand and consequential movements as in the past four years.”

A mad scramble to secure cotton for European industry ensued. The effort was all the more desperate as no one could predict when the war would end and when, if ever, cotton production would revive in the American South. “What are we to do,” asked the editors of the Liverpool Mercury in January 1861, if “this most precarious source of supply should suddenly fail us?” Once it did fail, this question was foremost on the minds of policy makers, merchants, manufacturers, workers, and peasants around the globe.

In the end, secession not only didn’t result in the coronation of King Cotton, but in fact spurred Europe to look to other sources of the staple. Go read Beckert’s whole piece.

____________

The Blockade and San Luis Pass

At the west end of Galveston Island lies San Luis Pass, a half-mile-wide channel between West Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. Deep-draft vessels could not get safely over the bar across its entrance, but it was a popular spot for smaller, mostly sailing vessels running in and out of West Bay. And consequently, it was a headache for the U.S. Navy, that never seemed to have enough ships to watch every part of the coast continuously.

I was coming back from Quintana this afternoon and snapped this image (top) from the bridge that now spans San Luis Pass. It’s a beautiful day here, but windy, and the water is rough. About a half mile away, you can see an almost continuous, horizontal white line of surf, with green water inside and blue water outside — those are the breakers on the bar that forced Pickering to release his prize and prisoners.

___________

An Unlikely Blockade Runner

The subject came up yesterday on another forum about the CW history of a particular vessel, the sidewheel riverboat William Bagaley (or Bagley, as it’s often given in contemporary records). It’s an interesting story.

William Bagaley was built at Belle Vernon, Pennsylvania in 1854. She was 170 feet long, 32 feet 9 inches wide (not including the sidewheels and deck overhang), and had a depth of hold of 7 feet. Her measured tonnage was 396 30/95 tons. She was initially registered at Pittsburgh on November 28, 1854.[1]

Abstract register of the steamboat William Bagaley, 1855.

The boat was re-enrolled about year later at New Orleans, on December 7, 1855. Her owner at that time was listed as Ralph Bagley (Bagaley?) of Pittsburg, and her master was John C. Sinnott. At some point in the following years it appears that Bagley may have sold his interest in the boat, because April 1861 the boat is advertised as being part of the Cox, Brainard & Co. line of steamers running between New Orleans and the Alabama River, as high up as Montgomery. Dick Sinnott is listed as master at that time; it’s not clear how he is related to John C. Sinnott, although they appear to be different individuals.[2]

April 1861 advertisement for the steamboat William Bagaley, running from New Orleans to Mobile, Selma and Montgomery. From Huber.

Sometime in mid-1862 or later, William Bagaley was taken into Confederate service, probably for use as a tender or supply vessel supporting the military outposts around Mobile Bay. On at least one occasion, in early March 1863, the steamer was used as a flag-of-truce vessel for communicating with the Union blockading fleet off the entrance to the bay.[3]

That spring and summer, Confederate officials in Mobile began hiring vessels to run the blockade to Cuba. Most of these, like Bagaley, were shallow-draft riverboats. The Confederate government would split the profits of the venture with the boats’ owners, and reimbrse them half the value of the vessel if she were lost. On the night of July 17/18, 1863, William Bagaley ran the blockade out of Mobile Bay, passing under the guns of Fort Morgan and keeping along the Swash Channel to the east of the entrance. Her cargo consisted of 700 bales of cotton, 3,200 barrel staves, and 125 barrels of turpentine.[4] She was under the command of Captain Charles Frisk, with 29 other crewmen on board. Running with her was the steamer James Battle, both headed for Havana. The two ships were spotted by the blockaders U.S.S. Aroostook and U.S.S. Kennebec. The division commander, Captain Jonathan P. Gillis also slipped his cable and gave chase in Ossipee. The Union vessels quickly overhauled James Battle, and Gillis ordered the commander of another blockader that had arrived on the scene, W. M. Walker of U.S.S. De Soto, to put a prize crew aboard and send the steamer on to New Orleans for adjudication. Gillis, in Ossipee, continued on after William Bagaley.[5]

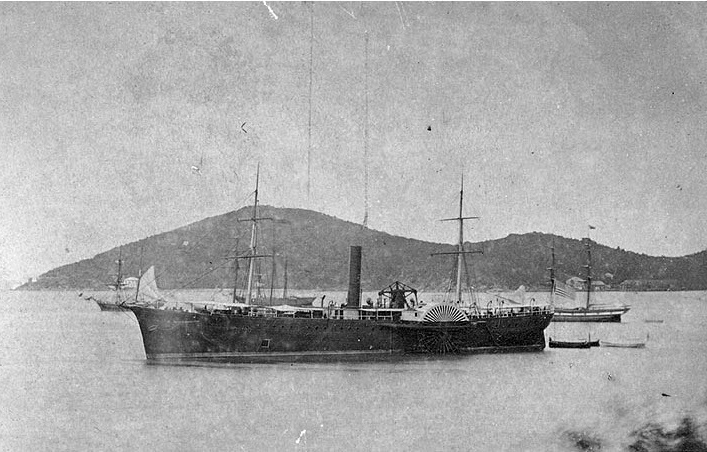

U.S.S. Ossipee in a postwar image, c. 1900. Library of Congress.

(It should be noted here that Kennebec, Aroostook and Ossipee were part of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, under the overall command of David G. Farragut, while De Soto was part of the East Gulf Blockading Squadron, under Theodorus Bailey. This divided command structure probably helped precipitate what happened next.)

By sunset that evening, Gillis could clearly make out the steamer up ahead. By 11 p.m. Ossipee was close enough to test the range with her 30-pounder rifle, at which the steamer immediately stopped her engines and hove to, waiting to be boarded. At that point they were about 176 nautical miles south-southeast of the entrance to Mobile Bay, more than a third of the distance to Havana. As Gillis was preparing to send a prize crew aboard, U.S.S De Soto churned up out of the darkness, stopped between Ossipee and her prize, and Walker began transferring his own prize crew. Gillis, who believed he had just made a solo capture – and thus making Ossipee and her crew eligible for the full award of prize money, was clearly incensed. He wrote in his report that he “doubted whether [De Soto] saw her, but had followed in our track, knowing we were in pursuit [and] seized clandestinely the opportunity in the darkness to throw on board a prize master and receive [the] steamer’s papers.” Gillis clearly saw Walker as poaching a share of a prize that was rightfully his. Gillis had Captain Frisk write out a statement that he had been chased by Ossipee since noon that day, that he had stopped in response to Ossipee’s gun, and “surrendered to the U.S.S. Ossipee.” Walker, for his part, formally reported to Gillis his taking possession of the prize, closing with the notation that “at the time of taking possession of the William Bagley the U. S. steamers Ossippee [sic.] and Kennebec were in sight.”[6]

U.S.S. De Soto at anchor in Puerto Rico, 1868. Naval Historical Center.

Walker’s notation about Ossipee and Kennebec being “in sight” at the time of capture is tremendously important, because U.S. Navy prize rules specified that all ships in sight or within signaling distance of a capture were entitled to a share of the proceeds, whether they had actively played a role in the capture or not. Not only did Walker dash in between Ossipee and Bagaley to claim the prize first, his mention of Kennebec being “in sight” at the time would effectively split the prize money three ways, reducing Gillis’ and Ossipee’s share by about two-thirds. Walker almost certainly believed that his own squadron commander, Rear Admiral Bailey, would defend Walker’s actions, particularly since a capture by one of the East Gulf Squadron’s ships would put prize money in Bailey’s own pocket.

Map showing the approximate location to the capture of the steamer William Bagaley.

Like James Battle, William Bagaley was sent in to New Orleans for adjudication at the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana. Bagaley arrived at New Orleans first, on July 23.[7] The court heard the case and condemned the steamer and its cargo on August 17, 1864, ordering them to be sold at public auction by the U.S. marshal, with De Soto and Ossipee listed as the official captors. A monition order was published in the local press giving ten days’ advance notice of the sale in the event there was a challenge, but none was forthcoming and the sale went ahead as scheduled.

Almost immediately after the auction, though – in fact, before the marshal could deposit the proceeds with the district court – a challenge to the sale was filed by a man from Indiana named Joshua Bragdon (1806-1875). Bragdon claimed to be a former resident of Mobile and a partner in the firm of Cox, Brainard & Co., that had owned the steamboat before the war. Bragdon claimed that, as a Union man, he had left Mobile and returned to his old home in Indiana at the outbreak of the war, while his partners remained in the South. More than a year after he went north, he said, the Confederacy had unlawfully seized his share in the boat, of which he claimed to hold a one-sixth interest. Bragdon insisted that he had never supported the rebellion and played no active role in it, and asked the court to award him one-sixth of the proceeds from the auction of both the steamer and her cargo, as being property that was rightfully his.

The district court in New Orleans rejected Bragdon’s claim and eventually the case made its way to the Supreme Court (The William Bagaley, 72 U.S. 5 Wall. 377). Remarkably, at this point Bragdon’s former partners also filed a motion with the Supreme Court, asking they be awarded the other five-sixths of the value of the ship and her cargo. They explained that while they had been Confederate citizens, they had subsequently been pardoned by President Johnson and were now ready to recover their lost investment, too.

In an opinion authored by Associate Justice Nathan Clifford (right, 1803-81), the court rejected both Bragdon’s and his former partners’ claims. The court held that Bragdon had effectively walked away from his property in Mobile and made no effort to remove or recover it for more than a year before it was seized by the Confederacy, effectively abandoning it. Bragdon claimed to have been loyal to the United States throughout the war, but Clifford wrote that with that loyalty came an obligation to break with his Confederate business partners and recover whatever interest he had in the boat. Ships, Clifford wrote, have a peculiar national identity that other forms of tangible property don’t, because they are formally registered, fly a national flag, and carry official government papers licensing their activities. By abandoning his vessel in what amounted to a foreign port during wartime, Bragdon had effectively handing over his interest in the vessel to the enemy government:

In an opinion authored by Associate Justice Nathan Clifford (right, 1803-81), the court rejected both Bragdon’s and his former partners’ claims. The court held that Bragdon had effectively walked away from his property in Mobile and made no effort to remove or recover it for more than a year before it was seized by the Confederacy, effectively abandoning it. Bragdon claimed to have been loyal to the United States throughout the war, but Clifford wrote that with that loyalty came an obligation to break with his Confederate business partners and recover whatever interest he had in the boat. Ships, Clifford wrote, have a peculiar national identity that other forms of tangible property don’t, because they are formally registered, fly a national flag, and carry official government papers licensing their activities. By abandoning his vessel in what amounted to a foreign port during wartime, Bragdon had effectively handing over his interest in the vessel to the enemy government:

For his part, Joshua Bragdon spent his remaining years in New Albany, Indiana, where he invested in a rolling mill. The 1870 U.S. Census identifies him as a manufacturer of T-rail — a high-demand item in the railroad-building boom of the postwar years — with a combined worth in real and personal property of $100,000. Bragdon died in 1875.

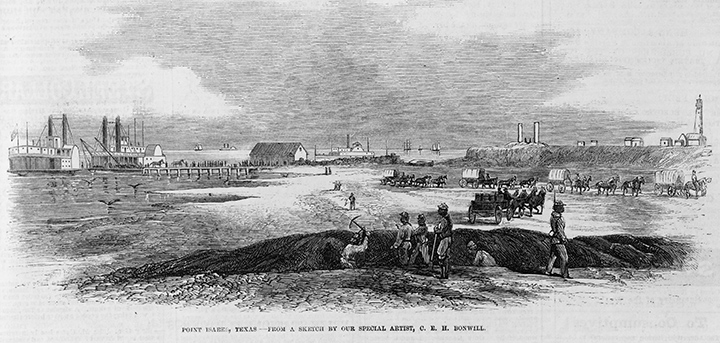

Federal troops at Point Isabel, Texas, as shown in a Febraruary 1864 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. At left are two riverboats, similar to William Bagaley, serving as Union army transports. Library of Congress.

By the time Justice Clifford wrote his opinion in 1866, though, the steamer William Bagaley was only a memory. The ship had been purchased at auction by the U.S. Quartermaster Department and outfitted as a transport for Nathaniel Banks’ expedition to the Texas coast. Bagaley was one of fourteen transports that sailed from the Southwest Pass of the Mississippi on October 26, 1863, bound for the anchorage at Brazos Santiago, near the mouth of the Rip Grande. A little over three weeks later, after offloading at Brazos Santiago, Bagaley was wrecked on the bar at Aransas Pass, near Corpus Christi, on November 18, 1863.[9]

Map from the OR Altlas showing the wreck location of Bagaley at Aransas Pass, Texas.

I don’t know if the wreck of William Bagaley has ever been located or identified, but if it survives it presumably lies in Texas state waters and, on that account, should be considered a protected archaeological landmark under the Texas Antiquities Code.

____________

[1] Works Progress Administration, Ship Registers and Enrollments of New Orleans, Louisiana, Vol. V: 1851-1860 (Louisiana State University, 1942), 272; Frederick Way, Jr., Way’s Packet Directory, 1848-1983 (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University, 1983), 487.

[2] Works Progress Administration, 272; Leonard V. Huber, Advertisements of Lower Mississippi River Steamboats, 1812-1920 (West Barrington, Rhode Island: Steamship Historical Society of America, 1959), 68.

[3] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies (hereafter cited as ORN), Volume 19, 656-57.

[4] The William Bagaley, 72 U.S. 5 Wall. 377 (1866, hereafter cited as Bagaley Case), (http://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/72/377/case.html).

[5] Stephen R. Wise, Lifeline of the Confederacy: Blockade Running During the Civil War (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1988), 171-72; ORN 17:504-07.

[6] ORN 17:507.

[7] New Orleans Times-Picayune, July 24, 1863, p. 2.

[8] Bagaley Case.

[9] Charles Dana Gibson and E. Kay Gibson, Assault and Logistics, Union Army Coastal and River Operations, 1861-1866 (Camden, Maine: Ensign Press, 1995), 336; ibid., 339; Charles Dana Gibson and E. Kay Gibson, Dictionary of Transports and Combatant Vessels, Steam and Sail, Employed by the Union Army, 1861-1868 (Camden, Maine: Ensign Press, 1995), 338.

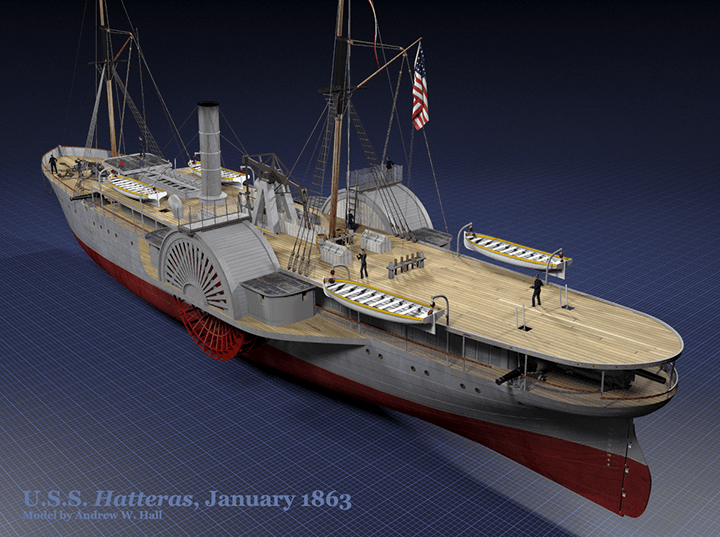

Aye Candy: U.S.S. Hatteras, Version 2.0

Updated renders of a digital model of U.S.S. Hatteras, a Union warship sunk in battle with the Confederate raider C.S.S. Alabama on January 11, 1863. This model replaces an earlier version that, while similar in general configuration, I now believe to be wrong in several respects. This model, which is about 75% new, is based on a detailed drawing of Hatteras‘ sister ship, the Morgan Line steamer Harlan (see that set), in the Bayou Bend Collection. Thanks to my colleague Ed Cotham for locating the Harlan image and sharing it with me. As always, full-resolution images available on Flickr.

![]()

________________

Wreck of U.S. Coast Survey Ship Identified

In 1852, W.A.K. Martin painted this picture of the Robert J. Walker. The painting, now at the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News, Va., is scheduled for restoration. (Credit: The Mariners’ Museum)

In 1852, W.A.K. Martin painted this picture of the Robert J. Walker. The painting, now at the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News, Va., is scheduled for restoration. (Credit: The Mariners’ Museum)

On Tuesday, the folks at NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program announced the identification of the wreck of the U.S. Coast Survey steamship Robert J. Walker, that was sunk in a collision with a sailing ship in June 1860 off the Jersey shore. From the announcement:

![]()

![]()

You can read a detailed, contemporary news account of the disaster, from the June 23, 1860 issue of the New York Commercial Advertiser here.

Videos from the wreck site are online here. The visibility is pretty lousy, but the exposed part of the wreck is similar in many ways to that of U.S.S. Hatteras, that was the focus os a NOAA-led expedition last year. Some of the preservation on the Walker site is remarkable. There are even remnants of what are believed to be wool blankets, that have been preserved by being covered in mud, in an anaerobic environment, until recently. (Hurricane Sandy may have played a role in exposing these materials.)

In her career as a survey vessel, Robert J. Walker probably served off Galveston, as she spent considerable time operating in the Gulf of Mexico. As it happens, her commanding officer during much of that period was Benjamin Franklin Sands (right, 1811-1883), whose first-hand knowledge of the hydrography of the Texas coast would prove useful some years later, when he commanded the Union squadron on blockade duty off Galveston during the closing days of the Civil War. It was Captain Sands who formally accepted Galveston’s surrender in June 1865, an event that effectively ended the Union blockade of Southern ports. You can download a high-res copy of one of Sands’ charts, compiled during his tenure aboard Robert J. Walker, here.

In her career as a survey vessel, Robert J. Walker probably served off Galveston, as she spent considerable time operating in the Gulf of Mexico. As it happens, her commanding officer during much of that period was Benjamin Franklin Sands (right, 1811-1883), whose first-hand knowledge of the hydrography of the Texas coast would prove useful some years later, when he commanded the Union squadron on blockade duty off Galveston during the closing days of the Civil War. It was Captain Sands who formally accepted Galveston’s surrender in June 1865, an event that effectively ended the Union blockade of Southern ports. You can download a high-res copy of one of Sands’ charts, compiled during his tenure aboard Robert J. Walker, here.

Congrats to NOAA’s Maritime Heritage Program and all its partners in this endeavor.

_____________

Aye Candy: The Confederate Ironclad That Almost Was

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8524/8587301585_4855a4e2ec_b.jpg)

This model of the Confederate casemate ironclad Wilmington is based on reconstruction plans drawn in the 1960s by W. E. Geoghagen, a maritime specialist at the Smithsonian Institution. Geoghagen’s drawings, in turn, are based on surviving plans prepared by the Confederate Navy’s Chief Constructor, John L. Porter (1813-1893). Full-size images are available on Flickr.

Wilmington was the last of three ironclads built at her namesake city during the Civil War. Neither of the first two had accomplished much during its service. The first, North Carolina, was structurally unsound and, like many of her type, was woefully underpowered. North Carolina was used in the brackish Cape Fear River as a floating battery until she sank at her moorings in September 1864, her bottom eaten through by teredo. The second ironclad, Raleigh, had been completed in the spring of 1864 and sortied to attack the Union blockading fleet off Fort Fisher. Raleigh managed to drive off several blockaders but upon her return upriver grounded on a sandbar and broke her keel, effectively making her a total loss.

Construction on the new ironclad began soon after Raleigh’s loss, in the late spring of 1864. In designing the vessel, Porter sought to remedy two serious flaws exposed by Raleigh’s brief sortie against the Union fleet: first, that she lacked sufficient speed to close the range and force a fight, and second, that she drew too much water to safely operate in the Cape Fear estuary.

Porter’s design is almost unique among Confederate ironclads, with a long length-to-beam ration of more than 6.5-to-1, perhaps in imitation of the long, fast blockade runners that operated between Wilmington, Bermuda and Nassau. The new ship, dubbed by locals as the future C.S.S. Wilmington, was unusual above deck, too. While almost all Confederate ironclads built or planned for construction in the Confederacy during the war followed the pattern set in 1862 by the famous C.S.S. Virginia (ex-U.S.S. Merrimack), by using a single, large armored casemate to house the ship’s battery, the vessel being built at Wilmington would have two small, low, casemates, each with a single, heavy gun working on a pivot on the inside. Each miniature casemate was fitted with seven ports, 45 degrees apart, giving the guns a wide (if narrowly segmented) field of fire. While the Confederacy lacked the resources to construct a revolving turret like those fitted on the Union Navy’s monitors, Porter’s design was a serious attempt to replicate the monitors’ greatest tactical advantages: all-around fire by a few, very heavy guns, and presenting the enemy’s gunners with a very small target. She is somewhat unusual for Confederate ironclads in that she was not built to be fitted with a ram.

Unfortunately, Wilmington never saw action, and was never formally commissioned. (Nor was the vessel ever officially named Wilmington; that’s what the locals called her.) She was still on the stocks, nearing completion, when the city of Wilmington was evacuated. This vessel, representing perhaps the most advanced design of ironclad built in the Confederacy during the war, was put to the torch to keep her from falling into the hands of Union troops.

Because Wilmington was never completed, we cannot know exactly how she would have appeared in service. Bob Holcombe, in his masters thesis “The Evolution of Confederate Ironclad Design” (East Carolina University 1993), notes that 150 tons of one-inch plate taken from the decrepit old North Carolina might have been intended for Wilmington’s open deck. In recreating the ship, I’ve left the deck unarmored, but I did put plating over the timbered knuckle that extends outboard on either side of the ship. This model represents a “what if” depiction of the ship as she might have looked if she’d been completed and fully commissioned, sometime in the summer of 1865. I don’t think this ship (or several of them) would’ve changed the overall equation at Wilmington and Fort Fisher, but it’s intriguing to imagine how she would have performed in action. With the right engines (probably a practical impossibility in that time and place) she might have been a real menace to the blockaders as a hit-and-run raider.

Special thanks to Kazimierz Zygadlo for his assistance in compiling material on this remarkable warship-that-almost-was.

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8527/8587301749_8f582fa25a_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8531/8588402400_5988740d2c_b.jpg) Alongside the Union river monitor U.S.S. Onondaga, for comparison.

Alongside the Union river monitor U.S.S. Onondaga, for comparison.

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8227/8587302463_82a66cae63_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8105/8587302829_850ca88059_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8505/8588403410_51cb1d9769_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8531/8588403814_02fd6edeef_b.jpg)

________________

![]()

Third Assistant Engineer William Francis Law, U. S. Navy

The other day, when I was poking around the web for images to go with my post on the H. L. Hunley spar, I came across this image (right) of a U.S. Navy engineer officer. My immediate reaction was, that’s a kid dressed up in somebody’s uniform. But it’s not; the notation on the back of the CDV reads, “Uncle Will Law as a Naval Officer Civil War.” Uncle Will was Third Assistant Engineer William Francis Law, appointed in November 1861. Law died on September 24, 1863 of unstated causes.

The other day, when I was poking around the web for images to go with my post on the H. L. Hunley spar, I came across this image (right) of a U.S. Navy engineer officer. My immediate reaction was, that’s a kid dressed up in somebody’s uniform. But it’s not; the notation on the back of the CDV reads, “Uncle Will Law as a Naval Officer Civil War.” Uncle Will was Third Assistant Engineer William Francis Law, appointed in November 1861. Law died on September 24, 1863 of unstated causes.

I’ve been able to find very little about Law in readily-available sources. The second image in the auction lot is a photograph of U.S.S. New Ironsides, that served off Charleston; written on the back of that card, in the same hand, is the note “Uncle Will Law’s ship Civil War.” According to Porter’s Naval History of the Civil War, Law was serving aboard U.S.S. Pinola at the capture of New Orleans in April 1862, and was still part of her complement the following January 1, as part of Farragut’s West Gulf Blockading Squadron. It seems he turns up exactly once in the ORN, a one-sentence mention in a routine report from Commander James Alden to Farragut on September 14, 1862: “Mr. Law succeeded in repairing the Pinola by making a new stem to her Kingston valve.”

About Law’s civilian life, I’ve been able to find even less. He is almost certainly the William F. Law, age 17, who was the eldest child of Benedict and Anna C. Law of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, just west of Harrisburg, at the time of the 1860 U.S. Census. He graduated from the Carlisle Boy’s High School in 1858 and, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer of June 28, 1861, graduated from the Polytechnic College of Pennsylvania with a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering, specializing in road building. Polytechnic was one of only a handful of universities in the United States at that time that offered engineering degrees, and Law’s academic background may have set him a little apart from his fellow engineers. Seagoing engineers in that day, both in the Navy and in the merchant service, were more commonly men with practical experience on shore in machine shops, foundries or similar trades.

I haven’t been able to confirm Law’s service aboard U.S.S. New Ironsides, as indicated on the back of the auction house photo; his name does not appear on these lists of ship’s officers transcribed from the National Archives. If he did serve aboard that ship in the summer of 1863, he saw a tremendous amount of action off Charleston.

One final note — in his undated portrait, taken at the Bogardus studio on Broadway in New York, Third Assistant Law looks to be wearing a gold-braided hat borrowed from a much more senior engineering officer. Maybe the sword, too. Gotta look good for the folks back in Carlisle, I suppose.

______________

“The blockade at last.”

On July 2, 1861, the U.S. Steamer South Carolina appeared off the bar at Galveston, the first Federal warship to be positioned on the Texas coast since the state declared its secession several months before. South Carolina‘s commander, Captain James Alden, Jr. (right, 1810-77), later summarized the event in three brief sentences in a dispatch to the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles (ORN 16 576):

On July 2, 1861, the U.S. Steamer South Carolina appeared off the bar at Galveston, the first Federal warship to be positioned on the Texas coast since the state declared its secession several months before. South Carolina‘s commander, Captain James Alden, Jr. (right, 1810-77), later summarized the event in three brief sentences in a dispatch to the Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Welles (ORN 16 576):

I have the honor to report that I arrived here on the 2d instant, and immediately hoisted a signal for a pilot for the purpose of communicating with the shore. In a short time a pilot boat came off, bearing a flag of truce and a document, a copy of which is herewith sent. In reply to it I enclosed a copy of your declaration of blockade, with a single remark that I was sent here to enforce it, which I should do to the best of my ability.

Fortunately we have a fuller picture of the events of that day. The war was a new, untested thing — the shocking casualties of First Manassas were still almost three weeks off — and both sides were still feeling each other out. From the Galveston Civilian and Gazette Weekly, July 9, 1861:

The Blockade at Last.

Yesterday forenoon the lookout on Hendley’s buildings ran up the red flag, signalizing war vessels, with the token for one sail and one steamer beneath, bringing groups of curious observers to the observatories with which Galveston is so well provided. In due time the dark hull of a large steam propeller loomed up above the waters, followed by a “low, black” but by no means “rakish looking schooner,” and approached the anchorage outside the bar.

By order of Capt. Moore, of the Confederate States Army, Capt. Thomas Chubb, with the pilot boar Royal Yacht, with our fellow citizen John S. Sydnor, proceeded to board the steamer, which proved to be the South Carolina, formerly in the New York and Savannah trade, but now converted into a war vessel.

The Royal Yacht, in answer to the pilot signal of the steamer, hoisted a flag; but the steamer evidently intended to force them to board the schooner; but this was not the intention. Capt. Chubb, on seeing the jack was down, put about for the city, being at the same time out of range, when the steamer hoisted a white flag. The Yacht then sent a boar alongside, bearing Col. Sydnor and Capt. Chubb. They were received with due ceremony and marked politeness. Col. Sydnor having delivered Capt. Moore’s letter, Capt., Alden gave him written notice of the blockade. A conversation of about an hour ensured, during which Capt. Alden was assured of the entire unity of our people in reference to resisting the oppression of the North. Capt. Alden expressed great regret that matters had reached such a pass, but said he was here to do his duty to his government, and that the intention was to enforce obedience to it. He gave no assurances as to the means which would be adopted to carry out his intentions as far as we are concerned.

The hatchways being closed and guns all covered, it was impossible to form any exact conclusions as to the strength of the steamer. She has six large guns, evidently 42 pounders, one large swivel near her bow, and at her stern two brass 6-pounders, all ready mounted for use as flying artillery. But a few men appeared on deck, and the only clue furnished as to her complement was in her clothing hanging up today. Capt. Chubb thinks there are about 150 on board.

Capt. Alden expressed the belief that his Government would soon be able to bring the Southern States into subjection, and, on being told that all classes of our people would suffer extermination first, seemed much surprised. He seemed disposed to converse freely in relation to our troubles, and received the plain talk and patriotic response on our two citizens on good humor. He said he was able to enforce the demands of his Government, and, if necessary, shell us out. He was assured that, whenever it came to that, we would give him a warm reception.

There was one feature in this affair worthy of note. Col. Sydnor is a native of the South, while Capt. Chubb was raised in the same town (Charleston, Mass.) with Capt. Alden. He was thus able to hear from his lips the unmistakable evidences that all our citizens of Southern, Northern, as well as foreign origin, are determined to fight to the last sooner than submit to the detestable rule of Lincoln.

The following is the reply of Capt. Alden to Capt. Moore’s note:

U.S. Steamer South Carolina

Off Galveston, July 2, 1861Capt. John O. Moore, C.S.A., & c.:

In answer to your communication of this date, I take the liberty of enclosing a declaration of blockade, which I am sent here to enforce, and amRespectfully your obedient servant,

James Alden, Com’r U.S. Steamer South Carolina____________

Declaration of Blockade

To all whom it may concern:

I, William Mervine, flag officer, commanding the United States naval forces comprising the Gulf squadron, give notice that, by virtue of the authority and power in me vested, and in pursuance of the proclamation of His Excellency the President of the United States, promulgated under date of April 19 and 27, 1861, respectively, that an effective blockade of the port of Galveston, Texas has been established, and will be rigidly enforced and maintained against all vessels (public armed vessels of foreign powers alone excepted) which attempt to enter or depart from said port.

Signed, William Mervine,

Flag Officer U.S. Flag Ship Mississippi, June 9, 1861.

I certify that the above is a true copy, James Alden, Com’r U.S. Navy.Neutral vessels will be allowed fifteen days to depart, from this date, viz., June [sic.] 2, 1861.

James Alden, Com’g.

The Hendley Buildings on Strand Street, Galveston, in the 1870s and in 2011. As one of the tallest commercial buildings in town at the time of the Civil War, the Hendley Buildings (or Hendley’s Row) were a natural lookout point for observers watching both the Gulf of Mexico and Galveston Bay. A red flag flown from this building on July 2, 1861 announced the much-anticipated arrival of the Federal blockade. Upper image: Rosenberg Library.

U.S.S. South Carolina, as drawn in 1948 by Eric Heyl. Via U.S. Naval Historical Center. South Carolina was built as a civilian packet steamer to operate on the Atlantic seaboard between Savannah, Charleston, Norfolk and Boston. She was iron-hulled, 217 feet long, 1,165 tons burthen. She served in the Gulf Blockading Squadron in 1861 and 1862, and spent the balance of the war with the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Sold out of the Navy after the end of hostilities, she became the civilian steamer Juanita in 1886. Her hull survived until 1902 when, as a barge, she foundered in a blizzard.

Additional details of the meeting between Alden, Chubb and Sydnor appeared in the New York Herald Tribune of July 31 quoting another Galveston paper:

In the course of the conversation, Capt. Alden expressed a desire to receive friendly visits from our citizens, and stated that he should especially be glad to have a visit from Gen. Houston. Col. Sydnor informed him, in reply, that though Gen. Houston had been a devoted Union man to the last, yet that now he had declared that he could no longer support the Stars and Stripes, but would fight to the last for the flag of the Confederate States. Capt. A. expressed his surprise and regret at this, and that his Government has no friends in Texas. But he said, nevertheless, he desired a friendly intercourse with our city, and hoped he might be hospitably received should he make us a visit.

Col. S. replied that he could not promise what kind of reception our authorities would give him. Capt. Alden inquired if there was not plenty of fish along our shore; he had heard there was, and he desired to catch some. He was informed that they were abundant along the beach, but that it might not be altogether prudent for his men to approach to near. Much of the conversation was in a jocular vein.

For all the strained humor about Alden’s interest in catching “fish,” both sides were in deadly earnest. Alden and South Carolina‘s crew wasted no time, celebrating the Fourth of July by capturing six small schooners, Shark, Venus, Ann Ryan, McCanfield, Louisa, and Dart. After providing his unwilling guests a large dinner in honor of the date, he sent them into Galveston under a flag of truce on Venus, McCanfield and Louisa, after judging those vessels worthless as prizes. The others Alden retained in hopes of fitting them with armament and using them for work in shallow water, close inshore.

For all the strained humor about Alden’s interest in catching “fish,” both sides were in deadly earnest. Alden and South Carolina‘s crew wasted no time, celebrating the Fourth of July by capturing six small schooners, Shark, Venus, Ann Ryan, McCanfield, Louisa, and Dart. After providing his unwilling guests a large dinner in honor of the date, he sent them into Galveston under a flag of truce on Venus, McCanfield and Louisa, after judging those vessels worthless as prizes. The others Alden retained in hopes of fitting them with armament and using them for work in shallow water, close inshore.

One of the freed passengers, curiously enough, was John A. Wharton (right, 1828-65), who would later command the 8th Texas Cavalry, Terry’s Rangers, and eventually rise to the rank of Major General in the Trans-Mississippi Department. According to the Herald Tribune, Wharton was allowed to keep his personal valise, but the military goods he was coming back to Texas with — two boxes of arms purchased for Brazoria County, ten gross of military buttons, cloth for military uniforms “and a six-shooter” — were all seized by Alden’s men as contraband.

But these initial moves were still just a prelude; a few weeks later, Captain Alden and South Carolina would open the war for real along the Texas coast.

______________

3 comments