Notes on Digital Modeling

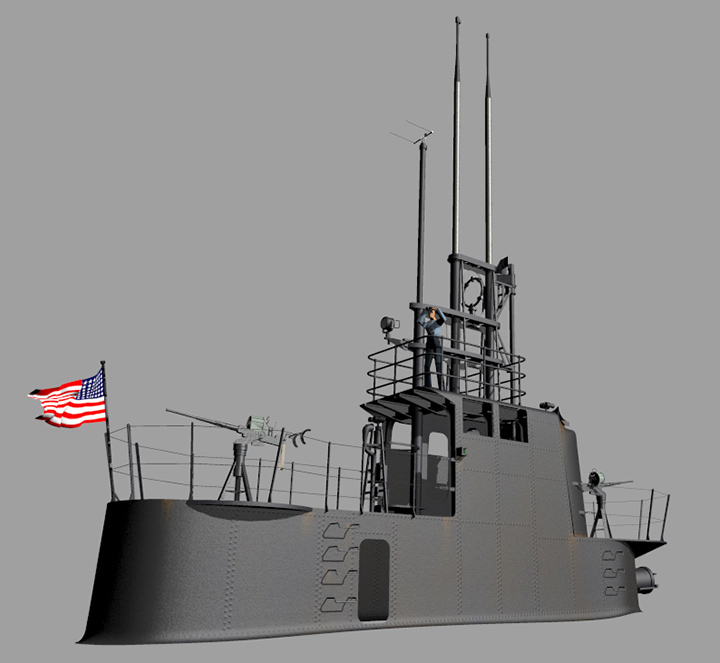

Conning tower of U.S.S. Cavalla (SS-244), as it appeared on her first war patrol in June 1944. In the 1950s Cavalla was refitted as a hunter-killer submarine (SSK), and in the process had her superstructure completely rebuilt, changing her external appearance permanently from what it was during World War II.

Conning tower of U.S.S. Cavalla (SS-244), as it appeared on her first war patrol in June 1944. In the 1950s Cavalla was refitted as a hunter-killer submarine (SSK), and in the process had her superstructure completely rebuilt, changing her external appearance permanently from what it was during World War II.

![]()

In the comments section of my recent posting with the digital model of the coastal steamship Harlan, a regular reader asked about the software I use and how I go about doing the modeling and renderings. In response to that, I’ll put down a few notes here that may give a little background to the process, at least how I fell into it. Don’t worry, this will not be a tutorial; I can’t stand to read those, either.

I should preface this by saying that the undercurrent that runs through all my history activities, of which I consider the modeling thing as one facet, is to convey whatever story or information to a wider and usually non-specialist audience– “public education” is the common term – and that influences the modeling somewhat. More on that in a bit.

The modeling software I’ve used for more than a decade is Rhinoceros, published by Robert McNeel & Associates. Rhino is not much used by hobbyists, but it works well for the sort of modeling I do, and (more important) was the first 3D package I used that I could actually figure out how to create something that turned out the way I wanted. (Like I said, I’m not good with tutorials.) Rhino is more commonly used in industry, particularly in marine engineering and naval architecture, in part because it’s optimized to interface well with various machine tools and digitizers. Many folks who create models in Rhino export them into other rendering software to create hyper-realistic images, but I usually use Rhino’s dedicated rendering application, Flamingo.

![]()

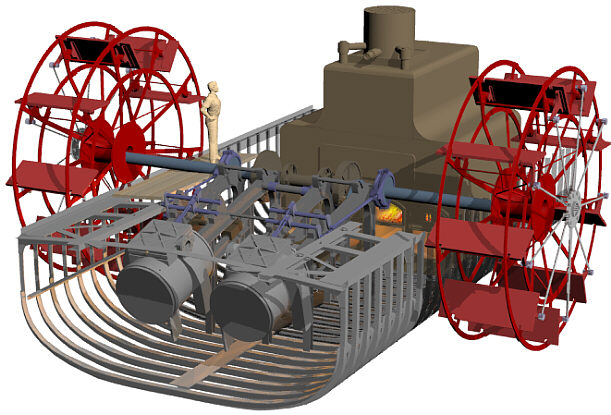

Model of the midships section of the blockade runner Denbigh, showing the engines, iron-framed paddlewheel, boiler and hull structure. Unlike most of my modeling projects, this one was based not on archival drawings, buton the aggregate data collected during three field seasons and hundreds of divers on the wreck site. Via Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

Model of the midships section of the blockade runner Denbigh, showing the engines, iron-framed paddlewheel, boiler and hull structure. Unlike most of my modeling projects, this one was based not on archival drawings, buton the aggregate data collected during three field seasons and hundreds of divers on the wreck site. Via Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

![]()

Some of my modeling has been done for specific projects or publications, a lot for fun, and some (like Harlan) for both. When I start a project, I compile all the images – photographs, scale drawings, whatever – that I can find to use as reference material. Inevitably some features on the model will be based on education guesswork, which is where experience and reference to similar subjects comes in handy. While I don’t have any detailed references on the arrangement of Harlan’s foredeck, for example, there’s lots of documentation of winches and other gear on similar vessels, so that can be reconstructed with a fair assurance that it’s representative of what was actually there.

In the case of Harlan, I had an excellent reference for the profile of the ship, showing its basic features, their position and proportions. I also had, from other sources, exact measurements of the ship – length, width, depth of hold, and so on. One critical thing I did not have (and that may not now exist), is a set of lines for the vessel, that precisely define the shape of the hull at regular intervals along its length. In the absence of that data, I used the lines of another iron-hulled vessel of that same general era, the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa, and scaled the dimensions of those lines to the known dimensions of Harlan. I reshaped the bow profile – gracefully curved on Elissa, straight and blade-like on Harlan – and made a few other small adjustments, and then used that shape for Harlan’s hull form. The result is an approximation, but probably close to what actually was there.

![]()

Hull form of the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa (foreground), and as adapted for the model of Harlan (background).

Hull form of the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa (foreground), and as adapted for the model of Harlan (background).

![]()

Other modelers may use different techniques, but some sort of “fudging” or guesswork is often necessary with 3D modeling. To produce a flat painting or drawing of a vessel or other object doesn’t necessarily require precision when it comes to complex shapes, but a digital model exists in three-dimensional space, so the modeler has to have something there. I’ve known lots of folks who’d say, “you don’t have the lines for that ship, so anything you put there is by definition incorrect, so you shouldn’t do it.” I understand that point, but I disagree with it, because I believe that the instructional value of an imperfect reconstruction, based on best evidence currently available, greatly outweighs the instructional value of a blank page. YMMV.

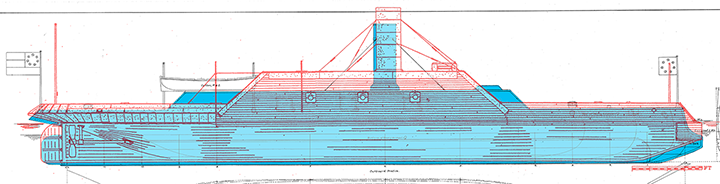

But getting back to using existing drawings, there’s a surprising amount of material available from different sources. Modern reconstructions are really dicey, though, because each draftsman ends up making assumptions and speculations that end up on the page, that may or may not be correct. To cite one example, I have reconstructed drawings done of the Confederate ironclad Arkansas by W. E. Geoghagan, a maritime history specialist working with Howard I. Chapelle at the Smithsonian Institution in the 1950s and ‘60s, and by David Meagher, a more recent researcher who’s compiled an impressive listing of reconstructed Civil War ironclads. Both men do fantastic work, but when you compare the two reconstructions, one over the other (Geoghagen in blue shading,, Meagher in red outline), it’s almost like they’re drawing two completely different ships:

![]()

Which one I think is more accurate, and why, is a subject for another time. But suffice to say that (1) any reconstructed reference drawing embodies its own speculative elements added by the draftsman, and (2) you can make yourself crazy trying to figure out which set of contradictory sources to use or, more likely, how to combine them to create something in-between.

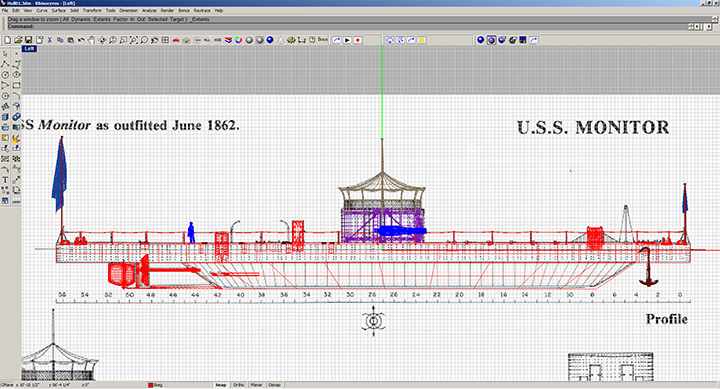

Anyway, good drawings from whatever source are central to my modeling process. Rhino and other modeling packages allow the user to drop images into the background of the workspace, so if you take time at the beginning to carefully align and scale those drawings, they serve as a template that you can draw directly over. This both accelerates the speed of the work and improves accuracy, insofar as the reference material itself is accurate.

![]()

Rhino workspace view of the model of U.S.S. Monitor. Note the upper left, lower left and lower right panes each have scale drawings of the ship, by Alan B. Chesley, for reference in modeling the ship.

Rhino workspace view of the model of U.S.S. Monitor. Note the upper left, lower left and lower right panes each have scale drawings of the ship, by Alan B. Chesley, for reference in modeling the ship.

Closeup of the lower right workspace pane, showing the use of Chesley’s profile as a reference. Different layers on the model are shown in different colors.

Closeup of the lower right workspace pane, showing the use of Chesley’s profile as a reference. Different layers on the model are shown in different colors.

![]()

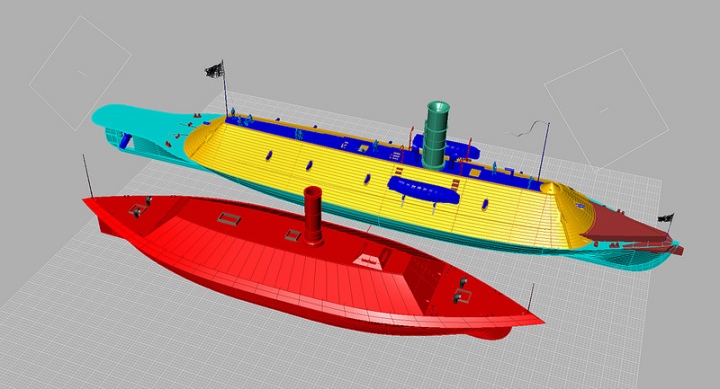

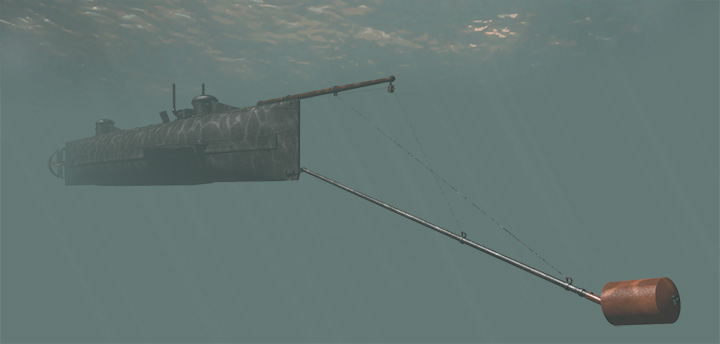

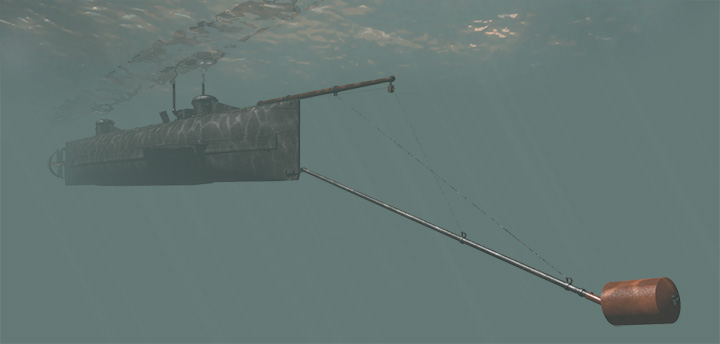

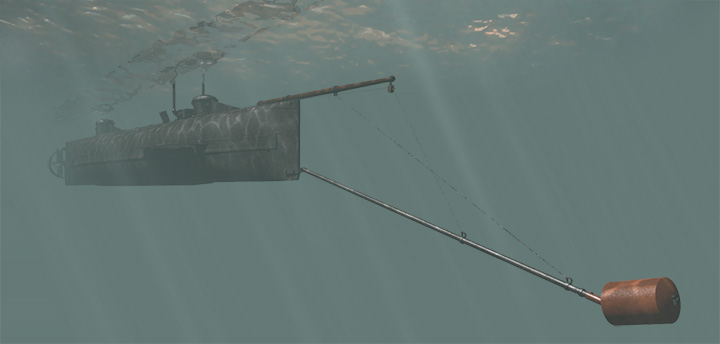

The software allows the user to group elements of the model together in “layers” that can be turned on or off, as needed. For clarity, the user assigns these different colors. Lots of models get very complex, very quickly, so it’s useful to be able to turn off layers that you’re not working on at a given moment. This is also useful for showing different aspects of the completed model. The Hunley model, for example, includes the spar torpedo in two different position, hoisted clear of the water and lowered in its deployed position; you just have to be careful to turn the two layers on and off alternately, to depict the boat in the appropriate configuration.

![]()

Workspace view of C.S.S. Virginia (above) and C.S.S. Richmond (below), showing on Virginia the different layers of the model, grouped by color.

Workspace view of C.S.S. Virginia (above) and C.S.S. Richmond (below), showing on Virginia the different layers of the model, grouped by color.

![]()

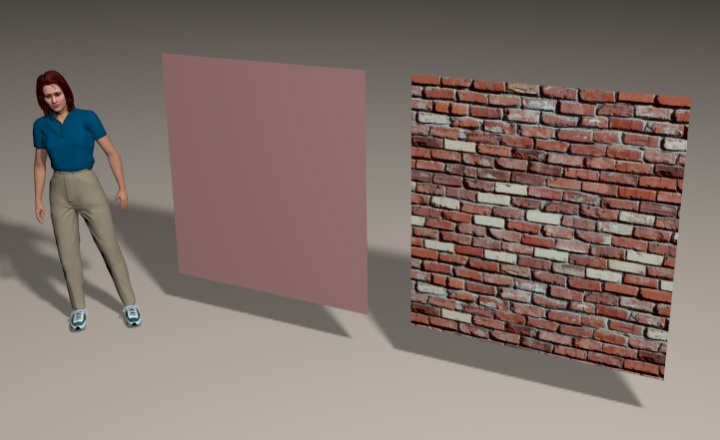

I also use a lot of ancillary software that are critical. I occasionally use Poser for figures (human or animal), and Photoshop constantly for developing textures and well as “post-production” work on the rendered model. Texture are images files (usually JPGs) that are projected onto the model to give it color and, um, texture. Applying a good texture – in this case, a photo of a brick wall — will make a simple plane into a substantial piece of masonry:

![]()

Two simple planes, the one on the right textured as a brick wall.

Two simple planes, the one on the right textured as a brick wall.

![]()

Finally, some images get a lot of “post” work after rendering, usually in Photoshop, to add elements that either the rendering software can’t do, or I don’t know how to do. For example, here’s a sequence with the Hunley model that takes it from an aseptic, obviously-a-model environment, and builds around it something that hopefully presents a more realistic depiction of how the boat might have appeared in real life:

1. Background color.

1. Background color.

2. Added light from surface.

2. Added light from surface.

3. Added light shafts for image background.

3. Added light shafts for image background.

4. Added rendered model of boat and spar torpedo.

4. Added rendered model of boat and spar torpedo.

5. Added reflection of boat on underside of water surface.

5. Added reflection of boat on underside of water surface.

6. Added light shafts in foreground, and the image is done.

6. Added light shafts in foreground, and the image is done.

![]()

Digital modeling has some advantages over building a physical model. Repetitive details (e.g., cannons or rail stanchions) can be exactly duplicated, over and over again, almost instantly. And if changes are needed, those can be accomplished much more readily with a digital model than a physical one. One reason I wanted to do Harlan is because she was of the same design as U.S.S. Hatteras, that I modeled some months ago; the Harlan digital model is currently being revised into a new and (I believe) more accurate rendering of Hatteras.

![]()

The updated Hatteras model.

![]()

Even so, digital models still lack the real beauty and style of a well-done physical model. It’s an aesthetic consideration, but it makes all the difference in the world. So now, go look at some real steamboat models by a real artisan, Rex Stewart.

___________

Is a Wirz Execution Photo Misidentified?

A repost on the 153rd anniversary of the event.

____________

Henry Wirz (1823-1865) remains one of the most controversial figures of the American Civil War. Reviled in the North for his role as commandant of the notorious Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia, Wirz was tried in the summer of 1865 in Washington, D.C. and condemned to death. He was hanged on November 10, 1865, on a scaffold set up in the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison (below), on what is now the site of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wirz continues to have many supporters, who argue that he did the best he could to care for the Federal soldiers imprisoned at Andersonville, with the very limited resources he had at his disposal. The Confederacy, they argue, had not sufficient means to care for its own population, much less enemy prisoners, and point to hard conditions in Northern prisons, where lack of resources was far less a problem, in response. They also point out that one of the key witnesses in the prosecution’s case against Wirz was apparently an imposter, who could not have witnessed the things he testified to under oath. Nearly a century and a half after his death, efforts are still being made to exonerate Wirz and restore his reputation.

This post isn’t about any of that.

Wirz’ execution was the subject of a famous sequence of four photographs, now part of the collection of the Library of Congress, taken by Alexander Gardner. The sequence of the photos, as indicated by both their captions and catalog numbers, is usually given as follows:

- Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold, LC-B817- 7752

- Adjusting the rope for the execution of Wirz, LC-B8171-7753

- Soldier springing the trap; men in trees and Capitol dome beyond, LC-B8171-7754

- Hooded body of Captain Wirz hanging from the scaffold, LC-B8171-7755

The four images were taken from three different locations (below). The first two appear to have been taken from the roof of the prison kitchen (Point A), looking diagonally across the yard where the scaffold is set up. For the image of Wirz’ body hanging from the beam, Gardner moved the camera to the left, and to a higher position to get a clearer view of the body in the trap (Point B). Gardner may have also wanted to frame his shot to capture the dome of the U.S. Capitol in the background. For the shot labeled “springing the trap,” the camera is again at a lower position, similar to the height of Point A, but still further to Gardner’s left (Point C), again with the dome of the Capitol in the background. Gardner’s framing of these last shots is not subtle.

Plan of the Old Capitol Prison, showing the approximate positions of Gardner’s camera during the Wirz execution sequence. The plan is undated (from here), but shows the facility during its use as a prison during and immediately after the Civil War, 1861-67.

After looking closely at these images, though, I believe that these last two are transposed chronologically; the third image, labeled “springing the trap,” is properly the last image in sequence, and shows Wirz’ body being lowered from gallows into the space below the scaffold. The evidence – and somewhat graphic images of the hanging – after the jump:

Is a Wirz Execution Photo Misidentified?

This post originally appeared on June 8, 2011.

_____________

Henry Wirz (1823-1865) remains one of the most controversial figures of the American Civil War. Reviled in the North for his role as commandant of the notorious Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia, Wirz was tried in the summer of 1865 in Washington, D.C. and condemned to death. He was hanged on November 10, 1865, on a scaffold set up in the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison (below), on what is now the site of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wirz continues to have many supporters, who argue that he did the best he could to care for the Federal soldiers imprisoned at Andersonville, with the very limited resources he had at his disposal. The Confederacy, they argue, had not sufficient means to care for its own population, much less enemy prisoners, and point to hard conditions in Northern prisons, where lack of resources was far less a problem, in response. They also point out that one of the key witnesses in the prosecution’s case against Wirz was apparently an imposter, who could not have witnessed the things he testified to under oath. Nearly a century and a half after his death, efforts are still being made to exonerate Wirz and restore his reputation.

This post isn’t about any of that.

Wirz’ execution was the subject of a famous sequence of four photographs, now part of the collection of the Library of Congress, taken by Alexander Gardner. The sequence of the photos, as indicated by both their captions and catalog numbers, is usually given as follows:

- Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold, LC-B817- 7752

- Adjusting the rope for the execution of Wirz, LC-B8171-7753

- Soldier springing the trap; men in trees and Capitol dome beyond, LC-B8171-7754

- Hooded body of Captain Wirz hanging from the scaffold, LC-B8171-7755

The four images were taken from three different locations (below). The first two appear to have been taken from the roof of the prison kitchen (Point A), looking diagonally across the yard where the scaffold is set up. For the image of Wirz’ body hanging from the beam, Gardner moved the camera to the left, and to a higher position to get a clearer view of the body in the trap (Point B). Gardner may have also wanted to frame his shot to capture the dome of the U.S. Capitol in the background. For the shot labeled “springing the trap,” the camera is again at a lower position, similar to the height of Point A, but still further to Gardner’s left (Point C), again with the dome of the Capitol in the background. Gardner’s framing of these last shots is not subtle.

Plan of the Old Capitol Prison, showing the approximate positions of Gardner’s camera during the Wirz execution sequence. The plan is undated (from here), but shows the facility during its use as a prison during and immediately after the Civil War, 1861-67.

After looking closely at these images, though, I believe that these last two are transposed chronologically; the third image, labeled “springing the trap,” is properly the last image in sequence, and shows Wirz’ body being lowered from gallows into the space below the scaffold. The evidence – and somewhat graphic images of the hanging – after the jump:

Real Confederates Didn’t Know About Black Confederates

Kevin reminds us that today, January 8, is the sesquicentennial of Howell Cobb’s famous letter to the Secretary of War, James Seddon, rejecting the notion of enlisting slaves as Confederate soldiers. Under the circumstances, it’s worth revisiting this old post of mine from October 2010.

__________________________

Lots of folks are familiar with Howell Cobb’s famous line, offered in response to the Confederacy’s efforts to enlist African American slaves as soldiers in the closing days of the war: “if slaves make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” It was part of a letter sent to Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon, in January 1865:

The proposition to make soldiers of our slaves is the most pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began. It is to me a source of deep mortification and regret to see the name of that good and great man and soldier, General R. E. Lee, given as authority for such a policy. My first hour of despondency will be the one in which that policy shall be adopted. You cannot make soldiers of slaves, nor slaves of soldiers. The moment you resort to negro [sic.] soldiers your white soldiers will be lost to you; and one secret of the favor With which the proposition is received in portions of the Army is the hope that when negroes go into the Army they will be permitted to retire. It is simply a proposition to fight the balance of the war with negro troops. You can’t keep white and black troops together, and you can’t trust negroes by themselves. It is difficult to get negroes enough for the purpose indicated in the President’s message, much less enough for an Army. Use all the negroes you can get, for all the purposes for which you need them, but don’t arm them. The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong — but they won’t make soldiers. As a class they are wanting in every qualification of a soldier. Better by far to yield to the demands of England and France and abolish slavery and thereby purchase their aid, than resort to this policy, which leads as certainly to ruin and subjugation as it is adopted; you want more soldiers, and hence the proposition to take negroes into the Army. Before resorting to it, at least try every reasonable mode of getting white soldiers. I do not entertain a doubt that you can, by the volunteering policy, get more men into the service than you can arm. I have more fears about arms than about men, For Heaven’s sake, try it before you fill with gloom and despondency the hearts of many of our truest and most devoted men, by resort to the suicidal policy of arming our slaves.

No great surprise here; earnest and vituperative opposition to the enlistment of slaves in Confederate service was widespread, even as the concussion of Federal artillery rattled the panes in the windows of the capitol in Richmond. What’s passing strange, as Molly Ivins used to say, is that Howell Cobb is a central figure in one of the canonical sources in Black Confederate “scholarship,” the description of the capture of Frederick, Maryland in 1862, published by Dr. Lewis H. Steiner of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. In his account of the capture and occupation of the town, Steiner makes mention of

Over 3,000 Negroes must be included in this number [of Confederate troops]. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the Negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie-knives, dirks, etc. . . and were manifestly an integral portion of the Southern Confederate Army.

This passage is often repeated without critique or analysis, and offered as eyewitness evidence of the widespread use of African American soldiers by the Confederate Army. Indeed, Steiner’s figure is sometimes extrapolation to derrive an estimate of black soldiers in the whole of the Confederate Army, to number in the tens of thousands. But, as history blogger Aporetic points out, Steiner’s observation is included in a larger work that mocks the Confederates generally, is full of obvious exaggerations and caricatures, and is clearly written — like Frederick Douglass’ well-known evocation of Black Confederates “with bullets in their pockets” — to rally support in the North to the Union cause. It is propaganda. Most important, Steiner’s account of Black Confederates under arms is entirely unsupported by other eyewitnesses to this event, North or South. Aporetic goes on to point out the apparent incongruity of Steiner’s description of this horde being led by none other than Howell Cobb:

A drunken, bloated blackguard on horseback, for instance, with the badge of a Major General on his collar, understood to be one Howell Cobb, formerly Secretary of the United States Treasury, on passing the house of a prominent sympathizer with the rebellion, removed his hat in answer to the waving of handkerchiefs, and reining his horse up, called on “his boys” to give three cheers. “Three more, my boys!” and “three more!” Then, looking at the silent crowd of Union men on the pavement, he shook his fist at them, saying, “Oh, you d—d long-faced Yankees! Ladies, take down their names and I will attend to them personally when I return.” In view of the fact that this was addressed to a crowd of unarmed citizens, in the presence of a large body of armed soldiery flushed with success, the prudence — to say nothing of the bravery — of these remarks, may be judged of by any man of common sense.

The Black Confederate crowd doesn’t usually include this second passage describing the same event, or explain Cobb’s apparent profound amnesia when it comes to the employment of African Americans in Confederate ranks. How is it, one wonders, that the same Howell Cobb who supposedly led thousands of black Confederate soldiers into Frederick in 1862 found the very notion of enlisting African Americans into the Confederate military a “most pernicious idea” just twenty-seven months later? How is it that the general who called on his black troops to give three cheers, then “three more, my boys!” came to believe that “the day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution?” How is it that the commander of successful black soldiers felt that “as a class they are wanting in every qualification of a soldier?” But set aside Dr. Steiner’s propogandist account for the moment; it’s unreliable and unsupported by other sources. Events at Frederick aside, how is that Howell Cobb, in January 1865, was unaware of the thousands, or tens of thousands, of African Americans soldiers supposedly serving in Confederate ranks across the South?  Howell Cobb’s Confederate bona fides are unimpeachable, and throughout the war he was irrevocably tied in to both political and military affairs. In his career he was, in turn, a five-term U.S. Representative from Gerogia, Speaker of the U.S. House Representatives, Governor of Georgia, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Speaker of the Provisional Confederate Congress, and Major General in the Confederate Army. He was a leader of the secession movement, and was elected president of the Montgomery convention that drafted a constitution for the new Confederacy. For a brief period in 1861, between the establishment of the Confederate States and the election of Jefferson Davis as its president, Speaker Cobb served as the new nation’s effective head of state. In his military career, Cobb held commands in the Army of Northern Virginia and the District of Georgia and Florida. He scouted and recommended a site for a prisoner-of-war camp that eventually became known as Andersonville; his Georgia Reserve Corps fought against Sherman in his infamous “March to the Sea.” Cobb commanded Confederate forces in a doomed defense of Columbus, Georgia in the last major land battle of the war, on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865, the day after Abraham Lincoln died in Washington, D.C. Perhaps more than any other man, Howell Cobb’s career followed the fortunes of Confederacy — civil, political and military — from beginning to end. And yet, after almost four years of war and almost three years of commanding large formations of Confederate troops in the field, in January 1865 Howell Cobb seemingly remained unaware of the thousands, or tens of thousands, of African Americans now claimed to have been serving in Southern ranks throughout the war. It is passing strange, is it not?

Howell Cobb’s Confederate bona fides are unimpeachable, and throughout the war he was irrevocably tied in to both political and military affairs. In his career he was, in turn, a five-term U.S. Representative from Gerogia, Speaker of the U.S. House Representatives, Governor of Georgia, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Speaker of the Provisional Confederate Congress, and Major General in the Confederate Army. He was a leader of the secession movement, and was elected president of the Montgomery convention that drafted a constitution for the new Confederacy. For a brief period in 1861, between the establishment of the Confederate States and the election of Jefferson Davis as its president, Speaker Cobb served as the new nation’s effective head of state. In his military career, Cobb held commands in the Army of Northern Virginia and the District of Georgia and Florida. He scouted and recommended a site for a prisoner-of-war camp that eventually became known as Andersonville; his Georgia Reserve Corps fought against Sherman in his infamous “March to the Sea.” Cobb commanded Confederate forces in a doomed defense of Columbus, Georgia in the last major land battle of the war, on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865, the day after Abraham Lincoln died in Washington, D.C. Perhaps more than any other man, Howell Cobb’s career followed the fortunes of Confederacy — civil, political and military — from beginning to end. And yet, after almost four years of war and almost three years of commanding large formations of Confederate troops in the field, in January 1865 Howell Cobb seemingly remained unaware of the thousands, or tens of thousands, of African Americans now claimed to have been serving in Southern ranks throughout the war. It is passing strange, is it not?

Of Submarines and Censorship

![]()

One of the common criticisms of the Lincoln administration during the Civil War is its efforts against members of the press and publishers who, in its view, were actively working to undermine the Union war effort. It helps to keep in mind, though, that pursuit and intimidation of the press by government or military authorities was nothing new in the 1860s, nor was was it confined to the perfidious Yankees. The conflict between the press, and those in authority, goes back as far as notions of the press being an independent of government, and of government needing support of the public — thus the incentive to try and exert control over the press. Those in authority will always seek to influence how they’re projected in the media, and sometimes this takes the form of raw intimidation.

I was reminded of this in re-reading Tom Chaffin’s 2008 book, The H. L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy. Chaffin picks up this thread in mid-October 1863, after the submarine sank for the second time in training, on this occasion taking her entire crew (including her namesake, Horace L. Hunley) to the bottom of the Cooper River, in front of scores of onlookers both afloat and on shore:

![]()

Whether it’s 1863 or 2013, a free press is always the bane of those in power. Always.

____________

Image: The Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley, by Conrad Wise Chapman. Via the Museum of the Confederacy.

Civil War Monitor for Fall 2013

“Without the fraternal bonds of soldiering or political and financial incentives, northern and southern women found little reason to commiserate. They might join with their counterparts across the Mason-Dixon line in the name of issues such as temperance, but remembering the war remained a whole other issue.” — Caroline E. Janney

“Without the fraternal bonds of soldiering or political and financial incentives, northern and southern women found little reason to commiserate. They might join with their counterparts across the Mason-Dixon line in the name of issues such as temperance, but remembering the war remained a whole other issue.” — Caroline E. Janney

The Fall 2013 issue of the Civil War Monitor made its online debut today, and it’s a good one. This issue includes:

![]()

- “Destination: Chickamauga,” by Sam Elliott and David A. Powell, a traveler’s guide to the must-see spots around that Georgia battlefield and in surrounding communities.

- “Napoleon Perkins Loses His Leg,” by Megan Kate Nelson, chronicling one soldier’s experience of being maimed on the battlefield.

- “Ironclads in Action,” one of the earliest examples of combat photography (taken 150 years ago Sunday!), by Bob Zeller of the Center for Civil War Photography.

- “Henry Lord Page King,” a profile of a Confederate staff officer killed at the Battle of Fredericksburg, by Stephen Berry.

- “Sherman’s Mississippi Raid” by Clay Mountcastle, an account of Kerosene Billy’s operations early 1864 that convinced him of the feasibility of what would later become known as the “March to the Sea.”

- “Why I Fight” by Matt Dellinger, with photos by Jonathan Kozowyk, profiling a dedicated Zouave reenactor.

- “An Act of War,” a collection of Jonathan Kozowyk’s portraits of Civil War reenactors.

- “The Puritan and the Cavalier” by Jeffery D. Wert, exploring the unlikely friendship between Stonewall Jackson and J. E. B. Stuart.

- “Hell Hath No Fury,” by Caroline E. Janney, documenting the role that women played in keeping wartime passions alive in the decades after the war, even as the veterans themselves settled into reconcilliation.

- “Memoirs: The Ultimate Confederate Primary Sources,” an appreciation of postwar autobiographies by Robert K. Krick.

![]()

Good stuff, all of it. The Fall 2013 issue of the Civil War Monitor should be appearing on newsstands and in subscribers’ mailboxes soon. Considering a subscription? Click here.

______________

Aye Candy: U.S.S. Hatteras, Version 2.0

Updated renders of a digital model of U.S.S. Hatteras, a Union warship sunk in battle with the Confederate raider C.S.S. Alabama on January 11, 1863. This model replaces an earlier version that, while similar in general configuration, I now believe to be wrong in several respects. This model, which is about 75% new, is based on a detailed drawing of Hatteras‘ sister ship, the Morgan Line steamer Harlan (see that set), in the Bayou Bend Collection. Thanks to my colleague Ed Cotham for locating the Harlan image and sharing it with me. As always, full-resolution images available on Flickr.

![]()

________________

Petersburg Photo Update

Recently we had a discussion about this LoC photo, taken in the “Petersburg vicinity” at the close of the war. Tuesday evening I received this update from Ben Uzel, President of the Colonial Heights Historical Society, opposite the Appomattox River from Petersburg. I’m reposting his comment here, with permission:

Here’s the Harper’s Weekly image of Petersburg mentioned, via SonoftheSouth.net:

_______

“The value of this communication destroyed can not be expressed in words or money”

UPDATE, August 21: A reader identifies both the location and elements of this image.

A discussion came up elsewhere of this image, of a burned-out bridge and locomotive in Virginia. The Library of Congress caption is “Petersburg, Virginia (vicinity). Ruins of locomotive and railroad bridge across the Appomattox River.” It would be nice to identify the exact location, though. The LoC’s caption identifying it as being in the Petersburg “vicinity” is of limited use.

Looking at period maps, I can only tell of one railroad bridge across the Appomattox, that of the Weldon & Petersburg Railroad, and that was actually at Petersburg:

![]()

![]()

Although a few maps, like this one from the OR Atlas, suggest there might have been two, connected:

![]()

There are several references to the Navy Department being anxious to destroy this bridge in the ORN, such as this June 1862 letter from Assistant Secretery of the Navy Gustavus Fox to Flag Officer Goldsborough:

G.V. FOX Flag-Officer GOLDSBOROUGH.

![]()

Gotta love that line, “provided it is done before McClellan fights.” Heh. No rush, dood.

Hindsight about McClellan’s aggressiveness notwithstanding, Fox’s letter is really interesting, because in it he not only urges destruction of the bridge, but commits the government to up to $50,000 in extra expenditures in order to accomplish it — I think that’s pretty rare.

Fox wanted John Rodgers to do the job, but Rodgers though it was simply not plausible as a naval exercise, and suggested instead it might be better to recruit saboteurs to do the job:

![]()

Off City Point, June 22, 1862. SIR: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of the 21st instant in regard to burning the railroad bridge at Petersburg, Va. The subject had already engaged my attention, and I met the following difficulties: The gunboats can not send a boat on shore without danger of an ambush. Every movement is carefully watched by armed men. We are not able to communicate with the inhabitants except with danger to them and to us. I have concluded that in Norfolk or at Fortress Monroe, where free intercourse can be had with Union men, citizens of Virginia, must be sought the agents for this work. The Appomattox, scarcely wider than a canal, has its channel obstructed by vessels and lighters sunk in the bottom of the river. It runs through banks which absolutely command any rowboats upon its waters. We can not approach by steamers, and rowboats would be destroyed. When I last heard from Petersburg, about a month ago, by two deserters, there were some 6,000 or 7,000 troops there under General Huger. If I see any opportunity of carrying out the subject of your letter, I shall zealously do so. Very respectfully, your obedient servant, JOHN RODGERS,

Commander. Flag-Officer LOUIS GOLDSBOROUGH,

Commanding North Atlantic Blockading Squadron.

![]()

Goldsborough, caught between a Navy Department that wanted it done, like, yesterday, and a respected and capable subordinate who said, in effect, “this is a terrible idea,” cast about for an alternative:

![]()

Flag-Officer.

![]()

![]()

The “submarine propeller” he refers to is the submersible Alligator (above), which has an interesting history of its own, but was unsuccessful in an attempt to destroy the bridge at Petersburg. Goldsborough subsequently followed Rodgers’ advice and recruited saboteurs to do the job:

![]()

Norfolk, Va., June 29, 1862. SIR: As the expedition up the Appomattox has not resulted favorably to the object it had in view, I have this day engaged two reliable persons, whose names I will give you hereafter, to proceed from this to the proper place and do the work. The men, I have every assurance, are entirely and thoroughly reliable. In the event of complete success each is to receive $25,000, and in case one of them should be taken and put to death for the destruction committed his brother in California is to receive $12,500, his sister in Richmond $6,250, and his stepsister, also in Richmond, $6,250. I have made confidential notes of the names, etc., of the parties, all of which will be duly forwarded when necessary. Commander Rodgers, as you will perceive by copies of communications from him which I forward by the mail of to-day, has, on finding the submarine propeller of no use to him, and for other reasons, sent it to Fort Monroe. Had I not better send it to Washington for safe keeping? At best it can only operate successfully in clear and tolerably deep water. All the experiments required by the Chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks can be much better conducted at Washington than here, particularly at this very critical conjuncture of our affairs hereabouts. Very respectfully, your most obedient servant, L.M. GOLDSBOROUGH,

Flag-Officer. Hon. GIDEON WELLES,

Secretary of the Navy, Washington City.

![]()

I’m not sure what, if anything, became of this mission, or how the bridge in the photograph came to be destroyed.

______

The other thing that’s interesting is that in his memo of June 20, Fox mentions a second bridge, on the same north-south route, over Swift Creek, north of Petersburg, on the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad:

![]()

![]()

Given that LoC captions — usually based on notations that come with the image when they’re transferred to them — are oftentimes imprecise, I believe this image of the burned bridge and locomotive may not be on the Appomattox River at all, but may be of the remains of the bridge at Swift Creek. (The LoC has a bunch of images of Federal gunboats captioned as being on the Appomattox, while I feel sure they’re actually on the James.)

Rodgers complained about the hazards of navigating the Appomattox River to Petersburg, but the waterway shown here, even given the seasonal rise and fall of creeks and rivers, isn’t enough to run an aluminum john boat. The course of the river shown in the image — turning sharply left in the background — seems to be a better fit for the Swift Creek crossing than for Petersburg. Note also that the banks are low here, contra Rodgers’ description of the Appomattox River around Petersburg.

Thoughts?

___________

The White Lies of Paula Deen

You’re all familiar with the dust-up over Paula Deen’s comments on race (admitted and alleged), and there’s no point rehashing that mess again here. But I would like to throw a little historical light on something she last year, referring to her g-g-g-grandfather, John A. Batts of Lee County, Georgia:

He had lost his son, he had lost his war, he didn’t know how to deal with life with no one to help operate his plantation. . . . Between the death of his son, and losing all the workers, he went out I’m sure into the barn and he shot himself because he couldn’t deal with those kinds of changes, and they were terrific changes. . . . I feel like the South is almost less prejudiced because black folks played such an integral part in our lives. They were like our family.Note that Deen can’t quite bring herself to use the word “slave” — they’re “workers.”

Now, a lot of white Southerners buy into this line. They insist that their ancestors had nothing to do with slavery, or if they did, their slaves “were like our family” and they were uniformly kind and benevolent masters. It’s a comforting rationalization, usually based on exactly nothing more than several generations’ worth of family lore. But as we saw with the case of Andrew Chandler and Silas Chandler, the beloved stories held dear by the descendants of slaveholders are often very different from those descended from those who were enslaved.

What’s surprising about Deen’s case is that she seems to have made up this tale about her ancestor on her own, and quite recently. Because until a year or so ago, when Georgia College Professor Bob Wilson laid it out for her, Deen had no idea her ancestor had “workers.”

![]()

![]()

She also said, “If I could go back and talk to [John Batts], I would do everything in my power to convince him not to participate in the heinous act of slavery.”

But that was way back in 2012, and since then she’s convinced herself that Batts’ bondsmen and -women “were like our family.”

Believe me, I understand how disturbing it is to learn from a slave schedule that your g-g-g-grandfather was a slaveholder. But there’s nothing to be done about that. Deal.

There’s a whole lot more to John Batts’ story, though, and it doesn’t mesh very well with her image of a simple farmer, caught up in the turbulent time that ripped apart his “family” and deprived him of his “workers.”

John A. Batts was born in 1814 in Miller County, Georgia. He and his wife, Mary, relocated to Lee County sometime in the late 1830s, and John began to establish himself as a planter. By the late 1840s, Batts was representing Lee County on a regional committee to develop plans to build a railroad line through that part of the state to the Georgia Central Line at Macon.[1]

Batt’s service on the railroad committee may have been his entre into the political arena. From the mid-1850s, Batts ran for or served in a variety of elected offices. In 1856 he was a Democratic nominee to serve as a justice of the Georgia Inferior Court, which position may be where his title of “Judge Batts” was earned.[2] He served a term in the Georgia House of Representatives beginning in November 1857.[3] In August 1860, Batts was a Democratic delegate from Lee County to the state Democratic convention at Milledgeville, in support of the nomination of John C. Breckinrdige and Joseph Lane in the presidential election that year.[4] In the fall of 1860 Batts was elected to a seat in the State Senate. Batts was a member of the Georgia Senate when that state seceded from the Union, but was not a member of Georgia’s secession convention.[5]

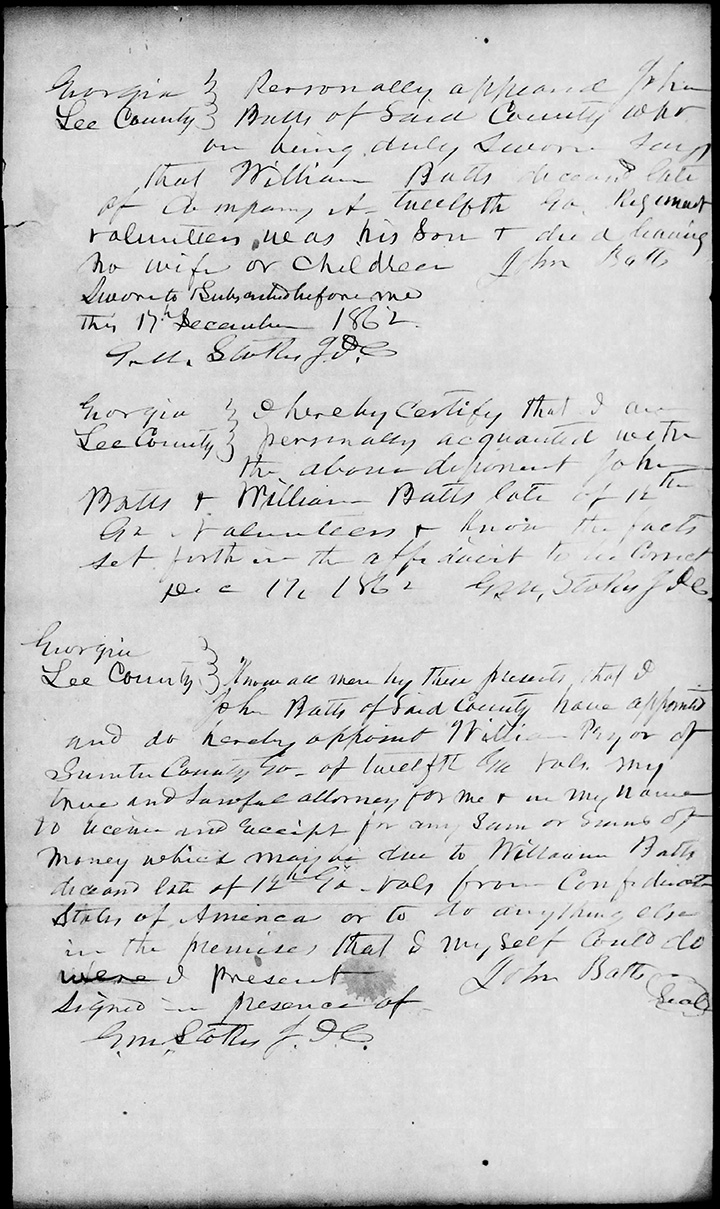

With the coming of the war, John and Mary Batts’ eldest son, William, enlisted as a Private in Co. A of the 12th Georgia Infantry. After William was killed in action at the Battle of Cedar Run on August 9, 1862, Judge Batts was obliged to swear an affidavit that his dead son left no wife or heirs, in order to claim $111.30 in bounty and back pay owed to the soldier.[6]

![]()

Judge Batts’ affidavit and power-of-attorney, filed to collect monies owed his deceased son, William.

In August 1865 John Batts applied for a formal pardon from the administration of President Andrew Johnson. Among the seventeen classes of persons ineligible for the general pardon were former Confederate citizens worth $20,000 or more. Batts applied, his application stating that “thus tho [Batts] doubts [that] he is worth twenty thousand dollars, yet he may be worth those sum [sic.] or more.” The affidavit goes on, asserting

![]()

![]()

John Batts had no trouble referring to his alleged “family” as his slaves; why does Paula Deen?

John Batts was not ruined financially by the war. Although he undoubtedly went through hard economic times like everyone else in the region, he had gone into the war period as a wealthy man, and remained so afterward. By the time of the U.S. Census of 1870, after a decade of war and Radical Reconstruction, John Batts still was able to list assets amounting to $18,000, $13,000 of that in land. He owned 2,250 acres, making him one of the largest landholders in Lee County. In the 20 years since the 1850 census, his real property holdings had more than doubled (up from 1,000 acres), and the amount of improved land tripled, from 350 acres in 1850 to 1,100 in 1870. In that latter year Batts’ holdings produced 1,500 bushels of corn, 300 bushels of oats, 141 bales of cotton, 300 pounds of wool and 500 bushels of sweet potatoes, with smaller amounts of other products, with an aggregate value of around $16,000.[8]

Beyond the hard numbers collected by the census enumerator, we also have a good narrative description of Batts’ plantation. That same summer, the Weekly Sumter Republican ran a letter describing the place:

![]()

![]()

At this point, it seems, many of the day-to-day operations of the farm were being handled by John Batts’ second son, Joseph, then aged about 25. (Joseph would go on to inherit the bulk of his father’s land holdings.) Nonetheless, John Batts appears to have remained active and engaged in his community during his last years, including participation in the Smithville Grange, a sort of farmer’s promotional group. [10]

But then, early one Sunday morning in the spring of 1878, Judge Batts put a pistol to his right temple and pulled the trigger. According to his surviving family members, he’d been suffering from depression “for months past,” and had tried several times to kill himself by ingesting morphine. According to one account, the old judge had “had many family troubles, which had partially dethroned his reason.” He was 63 years old.[11]

![]()

Batts’ death came thirteen years after the end of the war, thirteen years after emancipation, and seven years after the end of Reconstruction. The Redeemers, hard-line white conservative Democrats, again controlled the Georgia State Assembly and had purged its Republican, African American members. Batt’s farm – plantation, as it was still referred to – was bigger than it ever had been, and noted for its success.

Whatever torments haunted Judge Batts’ thoughts when he went out to the barn that morning in May 1878, we cannot know. I don’t know, you don’t know, and Paula Deen doesn’t know, either. It’s a personal tragedy that, at this distance, is probably impenetrable. William’s death at Cedar Run, all those years before, may well have played into John Batts’ deep and ultimately fatal depression. But beyond that, it’s speculation, without any real evidence at all. Paula Deen’s rationalization that Judge Batts’ suicide must have had something to do, fundamentally, with emancipation robbing him of his “family” is a perversion, a twisting of the story to make Batts – and by extension, herself — a victim of the end of slavery in the South. It’s selfish, and it’s shameful.

Even Judge Batts deserves better.

[1] Southern Recorder, May 25, 1847, 3.

[2] Albany, Georgia Patriot, April 3, 1856, 2.

[3] Journal of the House of Representatives of the State of Georgia (Milledgeville: Stare of Georgia, 1861).

[4] Federal Union, August 14, 1860. 3.

[5] Albany, Georgia Patriot, September 22, 1859, 2; Journal of the Senate of the State of Georgia (Milledgeville: Stare of Georgia, 1857), 5.

[6] Batts, William. Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Georgia, 12th Georgia Infantry, 1861-65 (NARA M266), National Archives.

[7] Batts, John. Case Files of Applications from Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons (“Amnesty Papers”), 1865-67 (NARA M1003), National Archives. “Genl Gilmore” is probably a reference to Major General Quincy Adams Gillmore, Commanding Officer of the U.S. Army’s Department of the South (South Carolina, Georgia and Florida) in the first half of 1865.

[8] 1870 U.S. Census for Lee County, Georgia; Schedule 1, Inhabitants, 12; 1870 U.S. Census for Lee County, Georgia; Schedule 3, Productions of Agriculture, 4-5; 1850 U.S. Census for Lee County, Georgia, Schedule 3, Productions of Agriculture, 147-49. At the time of the 1870 census, there were 19 landowners in Lee County, Georgia with farms amounting to 1,000 acres or more; Batts’ was more than twice that size. University of Virginia, Historical Census Browser. Retrieved July 4, 2013, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center: http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/index.html.

[9] Weekly Sumter Republican, July 15, 1870, 3. The writer’s impression of the overall efficiency of Batt’s farm seems to be correct, as the 1870 census suggests it had above-average production. While Batts’ 1,100 acres of improved cropland made up about 1.34% of Lee County’s total, his $16,000 in product made up about 1.58% of the county’s total agricultural production.

[10] Sun and Columbus Daily Enquirer, August 20, 1874, 3; Macon Telegraph and Messenger, August 18, 1874, 1

[11] August Weekly Sumter Republican, May 24, 1878, 3; Georgia Weekly Telegraph, May 28, 1878, 8; Columbus Daily Enquirer-Sun, May 23, 1878, 3.

___________

leave a comment