Notes on Digital Modeling

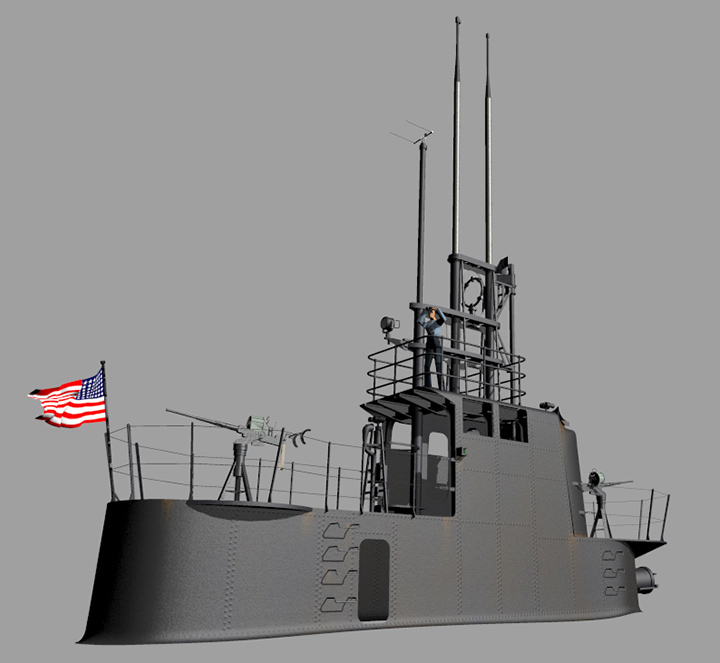

Conning tower of U.S.S. Cavalla (SS-244), as it appeared on her first war patrol in June 1944. In the 1950s Cavalla was refitted as a hunter-killer submarine (SSK), and in the process had her superstructure completely rebuilt, changing her external appearance permanently from what it was during World War II.

Conning tower of U.S.S. Cavalla (SS-244), as it appeared on her first war patrol in June 1944. In the 1950s Cavalla was refitted as a hunter-killer submarine (SSK), and in the process had her superstructure completely rebuilt, changing her external appearance permanently from what it was during World War II.

![]()

In the comments section of my recent posting with the digital model of the coastal steamship Harlan, a regular reader asked about the software I use and how I go about doing the modeling and renderings. In response to that, I’ll put down a few notes here that may give a little background to the process, at least how I fell into it. Don’t worry, this will not be a tutorial; I can’t stand to read those, either.

I should preface this by saying that the undercurrent that runs through all my history activities, of which I consider the modeling thing as one facet, is to convey whatever story or information to a wider and usually non-specialist audience– “public education” is the common term – and that influences the modeling somewhat. More on that in a bit.

The modeling software I’ve used for more than a decade is Rhinoceros, published by Robert McNeel & Associates. Rhino is not much used by hobbyists, but it works well for the sort of modeling I do, and (more important) was the first 3D package I used that I could actually figure out how to create something that turned out the way I wanted. (Like I said, I’m not good with tutorials.) Rhino is more commonly used in industry, particularly in marine engineering and naval architecture, in part because it’s optimized to interface well with various machine tools and digitizers. Many folks who create models in Rhino export them into other rendering software to create hyper-realistic images, but I usually use Rhino’s dedicated rendering application, Flamingo.

![]()

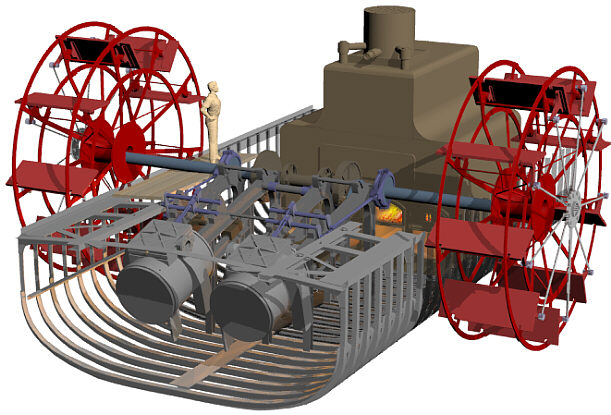

Model of the midships section of the blockade runner Denbigh, showing the engines, iron-framed paddlewheel, boiler and hull structure. Unlike most of my modeling projects, this one was based not on archival drawings, buton the aggregate data collected during three field seasons and hundreds of divers on the wreck site. Via Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

Model of the midships section of the blockade runner Denbigh, showing the engines, iron-framed paddlewheel, boiler and hull structure. Unlike most of my modeling projects, this one was based not on archival drawings, buton the aggregate data collected during three field seasons and hundreds of divers on the wreck site. Via Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

![]()

Some of my modeling has been done for specific projects or publications, a lot for fun, and some (like Harlan) for both. When I start a project, I compile all the images – photographs, scale drawings, whatever – that I can find to use as reference material. Inevitably some features on the model will be based on education guesswork, which is where experience and reference to similar subjects comes in handy. While I don’t have any detailed references on the arrangement of Harlan’s foredeck, for example, there’s lots of documentation of winches and other gear on similar vessels, so that can be reconstructed with a fair assurance that it’s representative of what was actually there.

In the case of Harlan, I had an excellent reference for the profile of the ship, showing its basic features, their position and proportions. I also had, from other sources, exact measurements of the ship – length, width, depth of hold, and so on. One critical thing I did not have (and that may not now exist), is a set of lines for the vessel, that precisely define the shape of the hull at regular intervals along its length. In the absence of that data, I used the lines of another iron-hulled vessel of that same general era, the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa, and scaled the dimensions of those lines to the known dimensions of Harlan. I reshaped the bow profile – gracefully curved on Elissa, straight and blade-like on Harlan – and made a few other small adjustments, and then used that shape for Harlan’s hull form. The result is an approximation, but probably close to what actually was there.

![]()

Hull form of the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa (foreground), and as adapted for the model of Harlan (background).

Hull form of the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa (foreground), and as adapted for the model of Harlan (background).

![]()

Other modelers may use different techniques, but some sort of “fudging” or guesswork is often necessary with 3D modeling. To produce a flat painting or drawing of a vessel or other object doesn’t necessarily require precision when it comes to complex shapes, but a digital model exists in three-dimensional space, so the modeler has to have something there. I’ve known lots of folks who’d say, “you don’t have the lines for that ship, so anything you put there is by definition incorrect, so you shouldn’t do it.” I understand that point, but I disagree with it, because I believe that the instructional value of an imperfect reconstruction, based on best evidence currently available, greatly outweighs the instructional value of a blank page. YMMV.

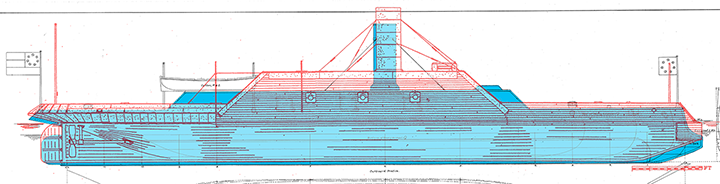

But getting back to using existing drawings, there’s a surprising amount of material available from different sources. Modern reconstructions are really dicey, though, because each draftsman ends up making assumptions and speculations that end up on the page, that may or may not be correct. To cite one example, I have reconstructed drawings done of the Confederate ironclad Arkansas by W. E. Geoghagan, a maritime history specialist working with Howard I. Chapelle at the Smithsonian Institution in the 1950s and ‘60s, and by David Meagher, a more recent researcher who’s compiled an impressive listing of reconstructed Civil War ironclads. Both men do fantastic work, but when you compare the two reconstructions, one over the other (Geoghagen in blue shading,, Meagher in red outline), it’s almost like they’re drawing two completely different ships:

![]()

Which one I think is more accurate, and why, is a subject for another time. But suffice to say that (1) any reconstructed reference drawing embodies its own speculative elements added by the draftsman, and (2) you can make yourself crazy trying to figure out which set of contradictory sources to use or, more likely, how to combine them to create something in-between.

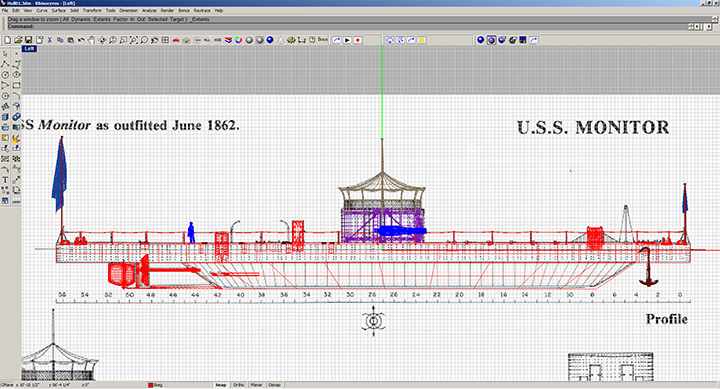

Anyway, good drawings from whatever source are central to my modeling process. Rhino and other modeling packages allow the user to drop images into the background of the workspace, so if you take time at the beginning to carefully align and scale those drawings, they serve as a template that you can draw directly over. This both accelerates the speed of the work and improves accuracy, insofar as the reference material itself is accurate.

![]()

Rhino workspace view of the model of U.S.S. Monitor. Note the upper left, lower left and lower right panes each have scale drawings of the ship, by Alan B. Chesley, for reference in modeling the ship.

Rhino workspace view of the model of U.S.S. Monitor. Note the upper left, lower left and lower right panes each have scale drawings of the ship, by Alan B. Chesley, for reference in modeling the ship.

Closeup of the lower right workspace pane, showing the use of Chesley’s profile as a reference. Different layers on the model are shown in different colors.

Closeup of the lower right workspace pane, showing the use of Chesley’s profile as a reference. Different layers on the model are shown in different colors.

![]()

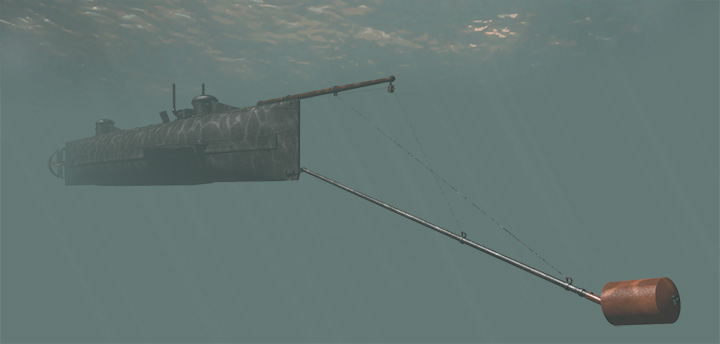

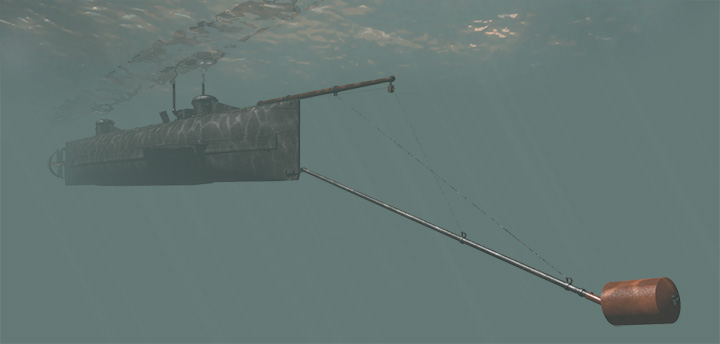

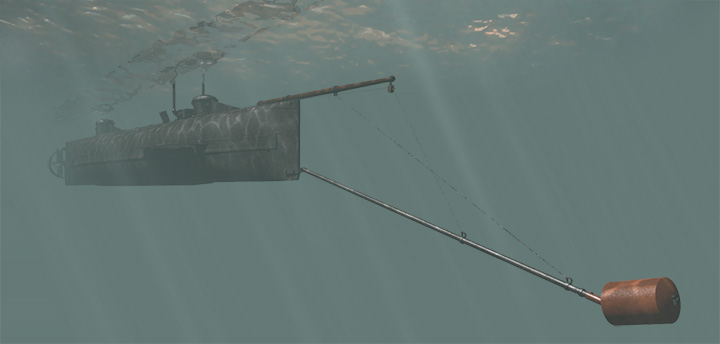

The software allows the user to group elements of the model together in “layers” that can be turned on or off, as needed. For clarity, the user assigns these different colors. Lots of models get very complex, very quickly, so it’s useful to be able to turn off layers that you’re not working on at a given moment. This is also useful for showing different aspects of the completed model. The Hunley model, for example, includes the spar torpedo in two different position, hoisted clear of the water and lowered in its deployed position; you just have to be careful to turn the two layers on and off alternately, to depict the boat in the appropriate configuration.

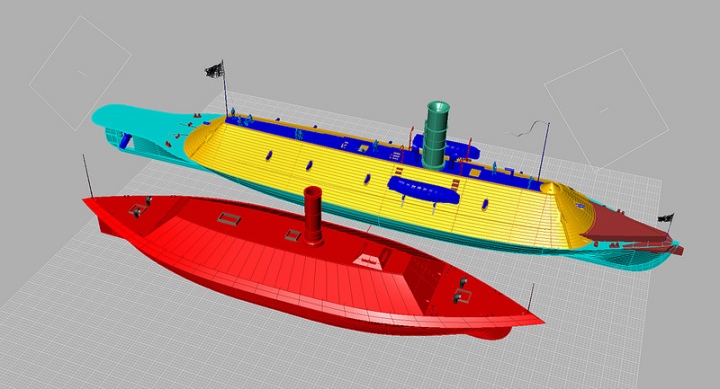

![]()

Workspace view of C.S.S. Virginia (above) and C.S.S. Richmond (below), showing on Virginia the different layers of the model, grouped by color.

Workspace view of C.S.S. Virginia (above) and C.S.S. Richmond (below), showing on Virginia the different layers of the model, grouped by color.

![]()

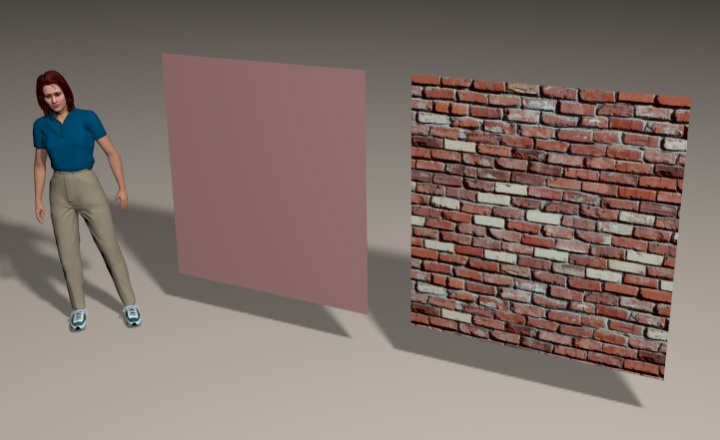

I also use a lot of ancillary software that are critical. I occasionally use Poser for figures (human or animal), and Photoshop constantly for developing textures and well as “post-production” work on the rendered model. Texture are images files (usually JPGs) that are projected onto the model to give it color and, um, texture. Applying a good texture – in this case, a photo of a brick wall — will make a simple plane into a substantial piece of masonry:

![]()

Two simple planes, the one on the right textured as a brick wall.

Two simple planes, the one on the right textured as a brick wall.

![]()

Finally, some images get a lot of “post” work after rendering, usually in Photoshop, to add elements that either the rendering software can’t do, or I don’t know how to do. For example, here’s a sequence with the Hunley model that takes it from an aseptic, obviously-a-model environment, and builds around it something that hopefully presents a more realistic depiction of how the boat might have appeared in real life:

1. Background color.

1. Background color.

2. Added light from surface.

2. Added light from surface.

3. Added light shafts for image background.

3. Added light shafts for image background.

4. Added rendered model of boat and spar torpedo.

4. Added rendered model of boat and spar torpedo.

5. Added reflection of boat on underside of water surface.

5. Added reflection of boat on underside of water surface.

6. Added light shafts in foreground, and the image is done.

6. Added light shafts in foreground, and the image is done.

![]()

Digital modeling has some advantages over building a physical model. Repetitive details (e.g., cannons or rail stanchions) can be exactly duplicated, over and over again, almost instantly. And if changes are needed, those can be accomplished much more readily with a digital model than a physical one. One reason I wanted to do Harlan is because she was of the same design as U.S.S. Hatteras, that I modeled some months ago; the Harlan digital model is currently being revised into a new and (I believe) more accurate rendering of Hatteras.

![]()

The updated Hatteras model.

![]()

Even so, digital models still lack the real beauty and style of a well-done physical model. It’s an aesthetic consideration, but it makes all the difference in the world. So now, go look at some real steamboat models by a real artisan, Rex Stewart.

___________

Is a Wirz Execution Photo Misidentified?

A repost on the 153rd anniversary of the event.

____________

Henry Wirz (1823-1865) remains one of the most controversial figures of the American Civil War. Reviled in the North for his role as commandant of the notorious Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia, Wirz was tried in the summer of 1865 in Washington, D.C. and condemned to death. He was hanged on November 10, 1865, on a scaffold set up in the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison (below), on what is now the site of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wirz continues to have many supporters, who argue that he did the best he could to care for the Federal soldiers imprisoned at Andersonville, with the very limited resources he had at his disposal. The Confederacy, they argue, had not sufficient means to care for its own population, much less enemy prisoners, and point to hard conditions in Northern prisons, where lack of resources was far less a problem, in response. They also point out that one of the key witnesses in the prosecution’s case against Wirz was apparently an imposter, who could not have witnessed the things he testified to under oath. Nearly a century and a half after his death, efforts are still being made to exonerate Wirz and restore his reputation.

This post isn’t about any of that.

Wirz’ execution was the subject of a famous sequence of four photographs, now part of the collection of the Library of Congress, taken by Alexander Gardner. The sequence of the photos, as indicated by both their captions and catalog numbers, is usually given as follows:

- Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold, LC-B817- 7752

- Adjusting the rope for the execution of Wirz, LC-B8171-7753

- Soldier springing the trap; men in trees and Capitol dome beyond, LC-B8171-7754

- Hooded body of Captain Wirz hanging from the scaffold, LC-B8171-7755

The four images were taken from three different locations (below). The first two appear to have been taken from the roof of the prison kitchen (Point A), looking diagonally across the yard where the scaffold is set up. For the image of Wirz’ body hanging from the beam, Gardner moved the camera to the left, and to a higher position to get a clearer view of the body in the trap (Point B). Gardner may have also wanted to frame his shot to capture the dome of the U.S. Capitol in the background. For the shot labeled “springing the trap,” the camera is again at a lower position, similar to the height of Point A, but still further to Gardner’s left (Point C), again with the dome of the Capitol in the background. Gardner’s framing of these last shots is not subtle.

Plan of the Old Capitol Prison, showing the approximate positions of Gardner’s camera during the Wirz execution sequence. The plan is undated (from here), but shows the facility during its use as a prison during and immediately after the Civil War, 1861-67.

After looking closely at these images, though, I believe that these last two are transposed chronologically; the third image, labeled “springing the trap,” is properly the last image in sequence, and shows Wirz’ body being lowered from gallows into the space below the scaffold. The evidence – and somewhat graphic images of the hanging – after the jump:

Is a Wirz Execution Photo Misidentified?

This post originally appeared on June 8, 2011.

_____________

Henry Wirz (1823-1865) remains one of the most controversial figures of the American Civil War. Reviled in the North for his role as commandant of the notorious Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia, Wirz was tried in the summer of 1865 in Washington, D.C. and condemned to death. He was hanged on November 10, 1865, on a scaffold set up in the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison (below), on what is now the site of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wirz continues to have many supporters, who argue that he did the best he could to care for the Federal soldiers imprisoned at Andersonville, with the very limited resources he had at his disposal. The Confederacy, they argue, had not sufficient means to care for its own population, much less enemy prisoners, and point to hard conditions in Northern prisons, where lack of resources was far less a problem, in response. They also point out that one of the key witnesses in the prosecution’s case against Wirz was apparently an imposter, who could not have witnessed the things he testified to under oath. Nearly a century and a half after his death, efforts are still being made to exonerate Wirz and restore his reputation.

This post isn’t about any of that.

Wirz’ execution was the subject of a famous sequence of four photographs, now part of the collection of the Library of Congress, taken by Alexander Gardner. The sequence of the photos, as indicated by both their captions and catalog numbers, is usually given as follows:

- Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold, LC-B817- 7752

- Adjusting the rope for the execution of Wirz, LC-B8171-7753

- Soldier springing the trap; men in trees and Capitol dome beyond, LC-B8171-7754

- Hooded body of Captain Wirz hanging from the scaffold, LC-B8171-7755

The four images were taken from three different locations (below). The first two appear to have been taken from the roof of the prison kitchen (Point A), looking diagonally across the yard where the scaffold is set up. For the image of Wirz’ body hanging from the beam, Gardner moved the camera to the left, and to a higher position to get a clearer view of the body in the trap (Point B). Gardner may have also wanted to frame his shot to capture the dome of the U.S. Capitol in the background. For the shot labeled “springing the trap,” the camera is again at a lower position, similar to the height of Point A, but still further to Gardner’s left (Point C), again with the dome of the Capitol in the background. Gardner’s framing of these last shots is not subtle.

Plan of the Old Capitol Prison, showing the approximate positions of Gardner’s camera during the Wirz execution sequence. The plan is undated (from here), but shows the facility during its use as a prison during and immediately after the Civil War, 1861-67.

After looking closely at these images, though, I believe that these last two are transposed chronologically; the third image, labeled “springing the trap,” is properly the last image in sequence, and shows Wirz’ body being lowered from gallows into the space below the scaffold. The evidence – and somewhat graphic images of the hanging – after the jump:

A Blue Norther (Revisited)

Galveston beachfront on the morning of January 3, 2014, with much more beach exposed than is usual, due to high, steady northerly winds.

Galveston beachfront on the morning of January 3, 2014, with much more beach exposed than is usual, due to high, steady northerly winds.

The same weather front that’s walloped the eastern United States over the last 48 hours has had its effect here on the supposedly-balmy Texas coast as well. The air temperature Thursday morning was in the mid-40s, but a sustain, 28 mph blast of wind from the north pushed the wind chill down to around freezing. The wind slacked a little during the day, but never let up completely. Sure enough, by overnight (January 2-3), the water in the upper part of the bay at Morgan’s Point had been blown down more than a foot (red Xs) from its predicted height (blue line) based on usual tidal cycles:

![]()

![]()

Under the circumstances, now seems like a good time to revisit a post I did about a year ago, on this somewhat unpleasant phenomenon.

![]()

Update, January 7: At around 8 a.m. on Monday, January 6 (“-16 hours”), the water level at Morgan’s Point was two feet below its normal level:

Cra. Zy.

In the winter of 1843-44, an Englishwoman by the name of Matilda Charlotte Houstoun (pronounced “Haweston”) visited Galveston twice with her husband, a British cavalry officer. The Houstouns were making a tour of the Gulf of Mexico, with Captain Houstoun trying to drum up interest in an invention of his for preserving beef. During their second visit, the Houstouns made a trip to Houston and back the 111-ton steamer Dayton, Captain D. S. Kelsey. On the trip back, the little steamer was delayed for two nights at Morgan’s Point, at the head of Galveston Bay, because a “norther” had blown so much water from the bay that it was impossible for the boat to get over nearby Clopper’s Bar, until the water rose again. The passengers went ashore and occupied their time in various ways; Captain Houstoun managed to shoot a possum, which was a novel creature to him. It was an object of brief curiosity until other passengers, more familiar with the fauna of Texas, appropriated it for the cook with the assurance that the animal was “first rate eating.”

![]()

Morgan’s Point and Clopper’s Bar, as shown on an 1856 U.S. Coast Survey chart of Galveston Bay. The soundings are in feet; any unusual reduction in the water level in the bay would make the bar impassible.

Morgan’s Point and Clopper’s Bar, as shown on an 1856 U.S. Coast Survey chart of Galveston Bay. The soundings are in feet; any unusual reduction in the water level in the bay would make the bar impassible.

![]()

“Northers” were new phenomena to the Houstouns, too, and in her travelogue Matilda Charlotte Houstoun gave a fine description of one:

They most frequently occur after a few days of damp dull weather, and generally about once a fortnight. Their approach is known by a dark bank rising on the horizon, and gradually overspreading the heavens. The storm bursts forth with wonderful suddenness and tremendous violence and generally lasts forty-eight hours; the wind after that period veers round to the east and southward, and the storm gradually abates. During the continuance of a norther, the cold is intense, and the wind so penetrating, it is almost impossible to keep oneself warm.

![]()

We had a norther here last week, a weather front that blasted through the area on the night of Wednesday/Thursday, part of the same front that caused hideous and deadly dust storms on the South Plains in Lubbock earlier. Down here, over 500 miles away, it left an orange dusting on cars and houses. Driving down to Angleton in Brazoria County along the Gulf on Thursday afternoon, my vehicle was continually buffeted by 25- to 30 mph winds, and an occasional higher gust, at a right angle to the road, pushing the car to the left, toward oncoming lanes of traffic. Not real fun.

But the most interesting aspect of this is one experienced by the Houstouns and others aboard Dayton almost 170 years ago, the effect of this strong, steady wind on local water levels. Historical accounts of bad weather will often include phrases like “blew the water out of the bay,” or something similar, and that’s not much of an exaggeration. Late Thursday evening, almost 24 hours after the front went through, I collected some graphics of meteorological and hydrologic data from Houston/Galveston Bay PORTS, a reporting system built and maintained by NOAA to provide real-time updates of conditions for those in the maritime industry. The graphics are small and a little difficult to read, but they provide direct, measured documentation of the sort of event described by so many mariners and travelers over the years. The data presented here are drawn from three different locations: Morgan’s Point, where Mrs. Houstoun and Dayton were stranded for two days; Pier 21 at Galveston, at the site of what was then known as Central Wharf, the steamboat’s destination; and Galveston Bay Entrance, a buoy along the channel through which marine traffic enters and leaves all the ports in the region — Galveston, Texas City, Houston, Baytown, and so on:

![]()

![]()

Let’s look at the data in some detail:

![]()

Wind speed at Morgan’s Point. This little chart shows the wind direction and speed for the period beginning about 4:30 a.m. on Thursday. The red dots show the sustained wind speed (scale on the y axis), while the blue arrows show its direction. For most of the period, right up until about 6 p.m., the wind blew steadily and consistently from the NNW at between 15 and 25 knots (17.3 to 28.8 mph), with gusts above that.

Wind speed at Morgan’s Point. This little chart shows the wind direction and speed for the period beginning about 4:30 a.m. on Thursday. The red dots show the sustained wind speed (scale on the y axis), while the blue arrows show its direction. For most of the period, right up until about 6 p.m., the wind blew steadily and consistently from the NNW at between 15 and 25 knots (17.3 to 28.8 mph), with gusts above that.

![]()

This chart shows the water levels at Morgan’s Point, from about 4:30 a.m. Thursday until late that evening. The narrow blue line represents the predicted height of the water at the tide gauge; it wavers a little bit based on the natural flow of the tide, which has a small normal range at that point. The red X marks are the actual, observed height of the water, which drops steadily with the wind over a period of about twelve hours, before leveling off and holding steady at more than two-and-a-half feet below the point known as “mean lower low water” (MLLW), the low-water standard that is used for navigational purposes. Note that the wind also wiped out almost any of the normal rise in the water level expected due to tidal action.

![]()

What about at the south end of Galveston Bay? Here’s the project vs. actual recorded water levels at Pier 21, along the Galveston wharf front:

![]()

Here, closer to the Galveston Bay entrance, tidal action has more effect, but the water level remains more than two feet lower than predicted.

Here, closer to the Galveston Bay entrance, tidal action has more effect, but the water level remains more than two feet lower than predicted.

![]()

This chart, plotting data from a buoy at the entrance to the bay, reveals an almost identical profile to that from Pier 21. Here, again, eighteen hours after the passage of the front, the water remains more than two feet below its predicted level based on tides alone.

![]()

These three charts show (top to bottom) wind speed and direction, air temperature and water levels at the entrance to Galveston Bay, for a 72-hour period ending about 10:30 p.m. on Thursday. Comparing these, it’s easy to see when the front passes in the early morning hours of Thursday, prompting dramatic changes in the wind, air temperature and water levels.

These three charts show (top to bottom) wind speed and direction, air temperature and water levels at the entrance to Galveston Bay, for a 72-hour period ending about 10:30 p.m. on Thursday. Comparing these, it’s easy to see when the front passes in the early morning hours of Thursday, prompting dramatic changes in the wind, air temperature and water levels.

![]()

Finally, one last chart, showing the sub-surface currents at the entrance to Galveston Bay, at 14, 21 and 27 feet (4.3, 6.4 and 8.2 meters) below the surface. You can see the normal tide effect for the first 48 hours on this chart, as the current shifts between a flood tide (above the dashed line, water going into the bay), and an ebb tide (below the dashed line) as it flows out again. Although the wind only acts on the surface of the water directly, the momentum it generates there is carried through into much deeper water, dramatically altering flow of water so much that even at a depth of 27 feet, the normal tidal action is so completely erased that it results in a net ebb of the tide, a full eighteen hours of water emptying from Galveston Bay into the Gulf of Mexico.

Finally, one last chart, showing the sub-surface currents at the entrance to Galveston Bay, at 14, 21 and 27 feet (4.3, 6.4 and 8.2 meters) below the surface. You can see the normal tide effect for the first 48 hours on this chart, as the current shifts between a flood tide (above the dashed line, water going into the bay), and an ebb tide (below the dashed line) as it flows out again. Although the wind only acts on the surface of the water directly, the momentum it generates there is carried through into much deeper water, dramatically altering flow of water so much that even at a depth of 27 feet, the normal tidal action is so completely erased that it results in a net ebb of the tide, a full eighteen hours of water emptying from Galveston Bay into the Gulf of Mexico.

![]()

How much water got “blown out of the bay” on this occasion? Some (very) rough estimates are possible. (Check my math, y’all.) If we take the difference between the predicted and observed water levels at the head of the bay (Morgan’s Point, -2.57 feet) and entrance to the bay (Galveston Bay Entrance, -2.08 feet), we can average between them a value of -2.33 feet. If we take that figure as representative of the water level of the bay as a whole (and that’s a big “if,” admittedly), then we can convert that vertical dimension into the volume of water it represents.

Galveston Bay encompasses about 600 square statute miles. One square mile is 27.88 million square feet; 600 square miles is 16.73 billion square feet. Multiply that by a depth of 2.33 feet, and you get a total volume of water of 38.98 billion cubic feet (1.1 billion cubic meters) of water.

That’s a lot of water; it would fill a cube-shaped aquarium 3,390 feet (1,033 meters), over a half-mile long, on each side. The water would weigh something on the order of 1.24 billion short tons, or 1.13 billion metric tonnes.

![]()

A 3,390-foot cube of seawater, approximating the volume of water blown out of Galveston Bay during the norther on December 20, 2012. Shown to scale are (top) a large, full-rigged sailing ship similar to Cutty Sark, (right) the statue of Liberty, and (left) the Petronas Towers in Malaysia, among the world’s tallest structures.

A 3,390-foot cube of seawater, approximating the volume of water blown out of Galveston Bay during the norther on December 20, 2012. Shown to scale are (top) a large, full-rigged sailing ship similar to Cutty Sark, (right) the statue of Liberty, and (left) the Petronas Towers in Malaysia, among the world’s tallest structures.

![]()

So much for the numbers. What does this mean in practical terms for navigation on Galveston Bay? Today, weather conditions like these still pose a problem, particularly the wind, which poses significant challenges for large vessels transiting the Houston Ship Channel. I suspect the problem is worse for down-bound vessels than up-bound, as the former are running with the wind and current, and are thus much more difficult to maneuver.

In the mid-19th century, the challenges of foul weather on the bay were substantially worse. The riverboats that ran between Galveston and Buffalo Bayou, Cedar Bayou, or the mouth of the Trinity River were very vulnerable, with their high superstructures and chimneys to catch the wind from any angle. (The little sternwheeler C. K. Hall, carrying a load of bricks out of Cedar Bayou, was sunk in just such a situation in 1871.) But the bigger problem then, before major dredging operations had established a deep and stable channel, was the depth of water over obstacles like Clopper’s Bar and Red Fish Bar, a nine-mile-long oyster reef curving in a gentle, east-west arc stretching completely across Galveston Bay, almost exactly halfway between Clopper’s Bar and Galveston Island. Red Fish Bar could, on occasion, cause significant damage to vessels, and at least one steamboat, Ellen P. Frankland, would be wrecked on the obstruction in the 1840s. Both Clopper’s Bar and Red Fish Bar could be crossed regularly by vessels drawing less than four feet, but this depth of water varied with the tide and weather.

![]()

Red Fish Bar, as shown on an 1856 chart of Galveston Bay. Soundings are given in feet.

Red Fish Bar, as shown on an 1856 chart of Galveston Bay. Soundings are given in feet.

![]()

I doubt that most of us in this area paid too much attention to the weather Thursday, apart from the inconvenience of the sudden drop in temperature and the wind. But it’s good to keep in mind how dramatically similar events sometimes affected the day-to-day lives of people in the past, and how fortunate we are to be sometimes that much more removed from them.

_____________

Aye Candy: U.S.S. Hatteras, Version 2.0

Updated renders of a digital model of U.S.S. Hatteras, a Union warship sunk in battle with the Confederate raider C.S.S. Alabama on January 11, 1863. This model replaces an earlier version that, while similar in general configuration, I now believe to be wrong in several respects. This model, which is about 75% new, is based on a detailed drawing of Hatteras‘ sister ship, the Morgan Line steamer Harlan (see that set), in the Bayou Bend Collection. Thanks to my colleague Ed Cotham for locating the Harlan image and sharing it with me. As always, full-resolution images available on Flickr.

![]()

________________

Aye Candy: Morgan Line Steamship Harlan, 1866

New renders of the Morgan Line steamship Harlan (seen previously here), that ran a coastwise route between New Orleans, Galveston and Indianola, Texas in the late 1860s and 1870s. New renders of the Morgan Line steamship Harlan, that ran a coastwise route between New Orleans, Galveston and Indianola, Texas in the late 1860s and 1870s. When she began the route in mid-1866, Harlan ran with three other steamships (Harris, Hewes and Morgan) on a 12-day cycle: New Orleans to Galveston (2 nights); after a brief stop at Galveston, on to Indianola (1 night); overnight at Indianola (1 night) then back to Galveston (1 night); a brief stop again at Galveston and back to New Orleans (2 nights). Fives nights at New Orleans, and then cycle repeats. A published schedule for the line (Galveston Daily News, June 13, 1866) gives the following for one of Harlan‘s voyages:

![]()

Harlan would depart New Orleans again on June 17. By running four ships on a schedule like this, there was a steamer departing each port every three or four days. Recall that at this time, there was no rail connection between Texas and the rest of the United States — that came later. The trip between Galveston and New Orleans is a long car ride now, but 150 years ago, a two-night trip aboard a coastal steamer like Harlan was both the fastest and most comfortable way to make the journey.

Harlan was the last of seven ships built to the same design by Harlan & Hollingsworth for the Morgan Line between 1861 and 1866. The first of these ships, St. Mary’s, was purchased new and converted into the Union warship U.S.S. Hatteras. In 1880, Harlan transported former President Grant and his party from Clinton, on Buffalo Bayou near Houston, to New Orleans.

Full-size images available on Flickr.

__________

More on the Petersburg Photo

![]()

Ben Uzel, President of the Colonial Heights Historical Society who identified the location of the Petersburg photo the other day, follows up:

The second attachment is a photo showing what the site looks like today. The southern river channel was filled in and is now covered by the Norfolk Southern track and a parking lot. Hope this adds to the interpretation.

The second attachment is a photo showing what the site looks like today. The southern river channel was filled in and is now covered by the Norfolk Southern track and a parking lot. Hope this adds to the interpretation.

![]()

It does indeed. Thanks!

______________

Stuck at Hanover Junction

Passengers at Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania, one of several images in the Library of Congress collection. I believe these pictures were taken on November 18 or 19, 1863, and may depict passengers stuck at Hanover Junction, unable to continue on to their intended destination at the dedication of the new National Cemetery at Gettysburg. See an enlargement here.

UPDATE: Scott Mingus got there first.

![]()

We talked the other day about the logistical difficulties of rail travel through wartime Richmond, Virginia, which was served by fine railroads, none of which connected to any another. As I mentioned in the piece, that was a common situation in the 1860s, across the country. As Bob Huddleston mentioned in the comments on that post, it was exactly that sort of situation in Baltimore that required the 6th Massachusetts to march through the center of that city, exposing them to mob violence in April 1861.

There’s another example of how disjointed rail travel could be in those days.Hanover Junction, Pennsylvania was a stop on the Northern Central Railway, that ran north from Baltimore, Maryland, into the middle of the Keystone State. It was the connection point with the Hanover Branch Railroad (also known as the Hanover and Gettysburg), that ran the 25 miles or so west to Gettysburg. From a history of that little railroad:

This original trackage of the Hanover Branch Railroad became one of real historical interest. It carried the parties of President Abraham Lincoln and Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin from Hanover Junction to Gettysburg on November 18, 1869, where on November 19, President Lincoln delivered his now famous “Gettysburg Address” at the dedication of the National Cemetery. The Northern Central trains carried President Lincoln from Baltimore and Governor Curtin from Harrisburg, the two groups meeting at Hanover Junction and proceeding together on the Hanover Branch to Gettysburg.

![]()

Simple enough, but there’s more to the goings-on at Hanover Junction during the Gettysburg dedication than that. It’s one of those stories that gets forgotten in the celebration, unless it happened to you. From the Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Patriot, November 26, 1863:

![]()

The Gettysburg Celebration. Dedication of the Great National Cemetery.In company with many others, we took the train for Gettysburg, via Hanover Junction, on Wednesday morning, to swell the ranks of the thronging thousands who, prompted by curiosity and patriotism or drawn by the tender ties of love for the dead, were gathering there to witness and participate in the the grand and solemn consecration of the burying place of the nation’s dead. . . .The train n which we rode was filled to its utmost capacity, many being forced to stand on the platform throughout the journey. The passengers were from all parts of the country, and almost every loyal State was represented in each car. The accommodation of the roads — the Northern Central and the Hanover and Gettysburg — were by no means sufficient for the occasion, and all persons going to or from the scene of interest were put to great inconvenience in consequence. Some were unable to get beyond Hanover Junction on Thursday. We saw a party of over fifty persons, who had journeyed over six hundred miles for the express purpose of attending the dedication, which party lay at the Junction from nine o’clock in the morning until ten at night, unable to get a step farther. Not a train was run over the Hanover road during that time, and this the pilgrims, after coming six hundred miles to see the battlefield, were defeated in their enterprise on the last twenty-five miles. It is a matter of wonder that, with such timely notice, this road failed to make proper arrangements, and suffered the spirit of mismanagement to paralyze its workings.

![]()

There are additional photos at the Library of Congress, apparently taken at the same time, of Hanover Junction. Some are attributed to Matthew Brady, and some assigned a date of 1863, but nothing more specific:

See an enlargement here.

See an enlargement here.

See an enlargement here.

See an enlargement here.

![]()

The LoC catalog listing provides no additional information on the date or subject of these images, but there are clues. The lack of vegetation on the trees suggests the images were made either early or late in the year. The clothing of the civilians is uniformly heavy, and mostly formal — these are not locals hanging around the depot to see who gets off the train. The soldiers all seem to be using canes, suggesting the effect of wounds. To me, these factors all suggest a date in late 1863. More specifically, I believe all three images are of parties traveling to or from the dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg on November 18 or 19, 1863 — maybe Governor Curtin’s party, or perhaps the delegation that had come 600 miles to witness the festivities, only to find themselves stuck in Hanover Junction. Either of those would be obvious subjects for a photographer. I don’t know if Brady traveled from Washington to Gettysburg, but Alexander Gardner was there. He had broken with Brady and had his own studio in Washington by the fall of 1863, and Gardner likely would have followed the same route by rail from Washington to Gettysburg, changing at Hanover Junction. Could these be Gardner photos from that event, misattributed (as much of his work was) to Brady? Or did Brady, coming up from Washington, also found himself stuck at Hanover Junction on the day of the dedication, and occupied his time shooting images of his fellow stranded passengers?

The 1863 station at Hanover Junction, by the way, still stands, apparently little changed from its appearance 150 years ago (via Google Maps):

Deep Gulf Shipwreck Project Wraps

Several pieces of the ship’s compass were found in the aft part of the vessel [during a site survey in 2012]. The compass card inside the gimbaled mount, shown here, is in an area where the ship’s binnacle would have been located. The two red dots at the bottom of the picture are laser lights that come from the ROV Little Hercules. ROVs often mount two parallel lasers to take measurements and these laser lights are 10 centimeters [2.54 inches] apart. Image courtesy NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program.

Several pieces of the ship’s compass were found in the aft part of the vessel [during a site survey in 2012]. The compass card inside the gimbaled mount, shown here, is in an area where the ship’s binnacle would have been located. The two red dots at the bottom of the picture are laser lights that come from the ROV Little Hercules. ROVs often mount two parallel lasers to take measurements and these laser lights are 10 centimeters [2.54 inches] apart. Image courtesy NOAA Okeanos Explorer Program.

![]()

Work on the Monterrey Wreck site wrapped earlier today, and the crew of E/V Nautilus is heading for the barn:

![]()

Coolness. Now the really revealing-but-un-glamorous work begins, with months of work in the lab to conserve, document and identify the artifacts recovered.

To get an idea of the depth at which this team was operating, check out a scale diagram of E/V Nautilus, the sled Argus and ROV Hercules after the jump.

Aye Candy: C.S.S. Richmond

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8528/8649710513_85afa8c710_b.jpg)

C.S.S. Richmond was one of the earliest Confederate ironclads, having been laid down at the Gosport Navy Yard at Norfolk, Virginia, in March 1862, immediately after the completion of the famous C.S.S. Virginia (ex-Merrimack). Richmond was designed by John Lucas Porter, who would go on to serve as the Chief Naval Constructor for the Confederacy, but completed under supervision of Chief Carpenter James Meads. Richmond embodied many of the basic design elements that be used, again and again, in other casemate ironclads built across the South in the following three years.

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8394/8649779153_94ebe92eae_b.jpg)

Richmond (red) along side C.S.S. Virginia, for scale.

When Union forces were on the verge of taking the Gosport Navy Yard, Richmond was hurriedly launched and towed up the James River, where she was completed at Richmond. Finally commissioned in July 1862, the ironclad served as a core element of the Confederate capital’s James River Squadron for the remainder of the war. Richmond, along with the other ironclads in the James, was destroyed to prevent her capture with the fall of her namesake city at the beginning of April 1865.

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8523/8649709571_a88a04298c_b.jpg)

This model is based on plans of the ironclad by David Meagher, published in John M. Coski’s book, Capital Navy: The Men, Ships and Operations of the James River Squadron, with modifications based on a profile of the ship by CWT user rebelatsea, particularly regarding the position of the ship’s funnel and pilot house. Hull lines are adapted from William E. Geoghagen’s plans for a later Porter design for an ironclad at Wilmington, that seems to have had an identical midship cross-section.

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8262/8649709355_a8269f760c_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8106/8649709825_def971ea71_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8522/8649710061_c8628c8415_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8385/8649710347_f243898f9a_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8528/8650809818_b75b3b888b_b.jpg)

As before, full-resolution images are available on Flickr. And here are two videos from the MoC featuring model builder Ozzie Raines, discussing the challenges of recreating this ship:

![]()

![]()

___________

leave a comment