Notes on Digital Modeling

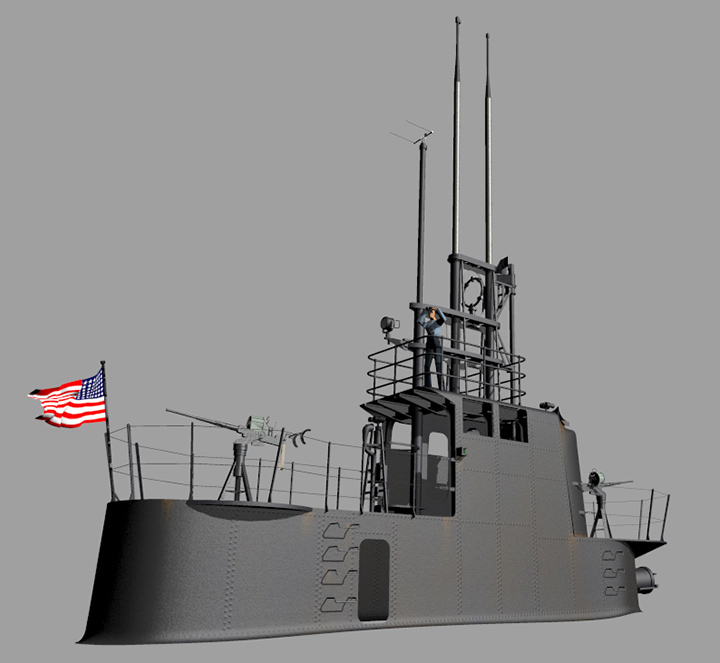

Conning tower of U.S.S. Cavalla (SS-244), as it appeared on her first war patrol in June 1944. In the 1950s Cavalla was refitted as a hunter-killer submarine (SSK), and in the process had her superstructure completely rebuilt, changing her external appearance permanently from what it was during World War II.

Conning tower of U.S.S. Cavalla (SS-244), as it appeared on her first war patrol in June 1944. In the 1950s Cavalla was refitted as a hunter-killer submarine (SSK), and in the process had her superstructure completely rebuilt, changing her external appearance permanently from what it was during World War II.

![]()

In the comments section of my recent posting with the digital model of the coastal steamship Harlan, a regular reader asked about the software I use and how I go about doing the modeling and renderings. In response to that, I’ll put down a few notes here that may give a little background to the process, at least how I fell into it. Don’t worry, this will not be a tutorial; I can’t stand to read those, either.

I should preface this by saying that the undercurrent that runs through all my history activities, of which I consider the modeling thing as one facet, is to convey whatever story or information to a wider and usually non-specialist audience– “public education” is the common term – and that influences the modeling somewhat. More on that in a bit.

The modeling software I’ve used for more than a decade is Rhinoceros, published by Robert McNeel & Associates. Rhino is not much used by hobbyists, but it works well for the sort of modeling I do, and (more important) was the first 3D package I used that I could actually figure out how to create something that turned out the way I wanted. (Like I said, I’m not good with tutorials.) Rhino is more commonly used in industry, particularly in marine engineering and naval architecture, in part because it’s optimized to interface well with various machine tools and digitizers. Many folks who create models in Rhino export them into other rendering software to create hyper-realistic images, but I usually use Rhino’s dedicated rendering application, Flamingo.

![]()

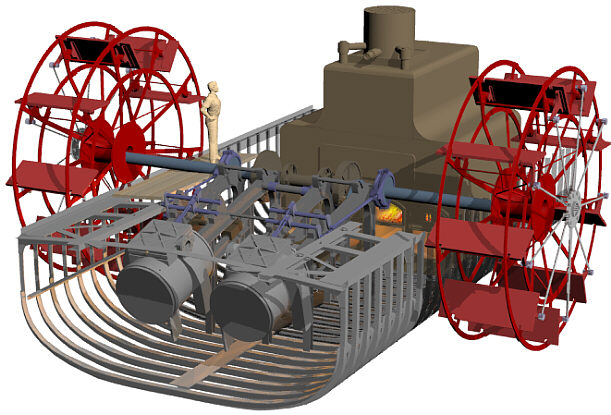

Model of the midships section of the blockade runner Denbigh, showing the engines, iron-framed paddlewheel, boiler and hull structure. Unlike most of my modeling projects, this one was based not on archival drawings, buton the aggregate data collected during three field seasons and hundreds of divers on the wreck site. Via Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

Model of the midships section of the blockade runner Denbigh, showing the engines, iron-framed paddlewheel, boiler and hull structure. Unlike most of my modeling projects, this one was based not on archival drawings, buton the aggregate data collected during three field seasons and hundreds of divers on the wreck site. Via Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

![]()

Some of my modeling has been done for specific projects or publications, a lot for fun, and some (like Harlan) for both. When I start a project, I compile all the images – photographs, scale drawings, whatever – that I can find to use as reference material. Inevitably some features on the model will be based on education guesswork, which is where experience and reference to similar subjects comes in handy. While I don’t have any detailed references on the arrangement of Harlan’s foredeck, for example, there’s lots of documentation of winches and other gear on similar vessels, so that can be reconstructed with a fair assurance that it’s representative of what was actually there.

In the case of Harlan, I had an excellent reference for the profile of the ship, showing its basic features, their position and proportions. I also had, from other sources, exact measurements of the ship – length, width, depth of hold, and so on. One critical thing I did not have (and that may not now exist), is a set of lines for the vessel, that precisely define the shape of the hull at regular intervals along its length. In the absence of that data, I used the lines of another iron-hulled vessel of that same general era, the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa, and scaled the dimensions of those lines to the known dimensions of Harlan. I reshaped the bow profile – gracefully curved on Elissa, straight and blade-like on Harlan – and made a few other small adjustments, and then used that shape for Harlan’s hull form. The result is an approximation, but probably close to what actually was there.

![]()

Hull form of the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa (foreground), and as adapted for the model of Harlan (background).

Hull form of the 1877 Iron Barque Elissa (foreground), and as adapted for the model of Harlan (background).

![]()

Other modelers may use different techniques, but some sort of “fudging” or guesswork is often necessary with 3D modeling. To produce a flat painting or drawing of a vessel or other object doesn’t necessarily require precision when it comes to complex shapes, but a digital model exists in three-dimensional space, so the modeler has to have something there. I’ve known lots of folks who’d say, “you don’t have the lines for that ship, so anything you put there is by definition incorrect, so you shouldn’t do it.” I understand that point, but I disagree with it, because I believe that the instructional value of an imperfect reconstruction, based on best evidence currently available, greatly outweighs the instructional value of a blank page. YMMV.

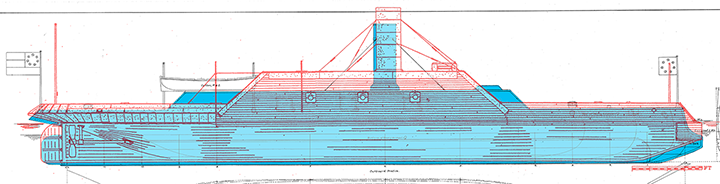

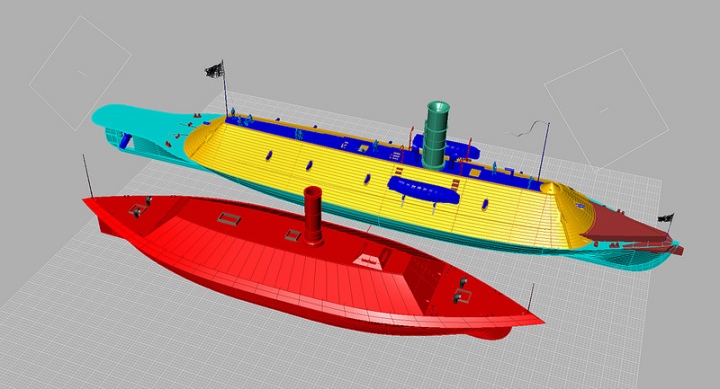

But getting back to using existing drawings, there’s a surprising amount of material available from different sources. Modern reconstructions are really dicey, though, because each draftsman ends up making assumptions and speculations that end up on the page, that may or may not be correct. To cite one example, I have reconstructed drawings done of the Confederate ironclad Arkansas by W. E. Geoghagan, a maritime history specialist working with Howard I. Chapelle at the Smithsonian Institution in the 1950s and ‘60s, and by David Meagher, a more recent researcher who’s compiled an impressive listing of reconstructed Civil War ironclads. Both men do fantastic work, but when you compare the two reconstructions, one over the other (Geoghagen in blue shading,, Meagher in red outline), it’s almost like they’re drawing two completely different ships:

![]()

Which one I think is more accurate, and why, is a subject for another time. But suffice to say that (1) any reconstructed reference drawing embodies its own speculative elements added by the draftsman, and (2) you can make yourself crazy trying to figure out which set of contradictory sources to use or, more likely, how to combine them to create something in-between.

Anyway, good drawings from whatever source are central to my modeling process. Rhino and other modeling packages allow the user to drop images into the background of the workspace, so if you take time at the beginning to carefully align and scale those drawings, they serve as a template that you can draw directly over. This both accelerates the speed of the work and improves accuracy, insofar as the reference material itself is accurate.

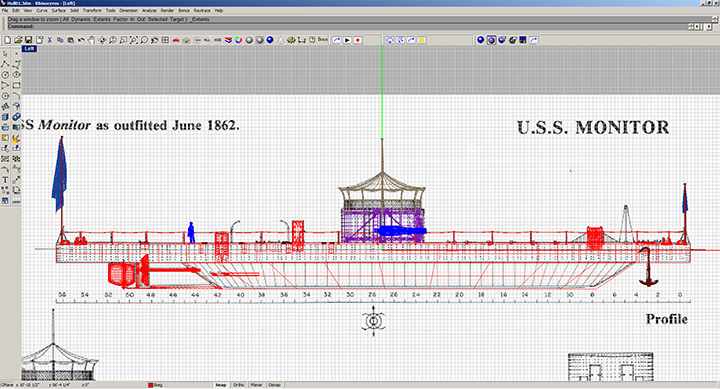

![]()

Rhino workspace view of the model of U.S.S. Monitor. Note the upper left, lower left and lower right panes each have scale drawings of the ship, by Alan B. Chesley, for reference in modeling the ship.

Rhino workspace view of the model of U.S.S. Monitor. Note the upper left, lower left and lower right panes each have scale drawings of the ship, by Alan B. Chesley, for reference in modeling the ship.

Closeup of the lower right workspace pane, showing the use of Chesley’s profile as a reference. Different layers on the model are shown in different colors.

Closeup of the lower right workspace pane, showing the use of Chesley’s profile as a reference. Different layers on the model are shown in different colors.

![]()

The software allows the user to group elements of the model together in “layers” that can be turned on or off, as needed. For clarity, the user assigns these different colors. Lots of models get very complex, very quickly, so it’s useful to be able to turn off layers that you’re not working on at a given moment. This is also useful for showing different aspects of the completed model. The Hunley model, for example, includes the spar torpedo in two different position, hoisted clear of the water and lowered in its deployed position; you just have to be careful to turn the two layers on and off alternately, to depict the boat in the appropriate configuration.

![]()

Workspace view of C.S.S. Virginia (above) and C.S.S. Richmond (below), showing on Virginia the different layers of the model, grouped by color.

Workspace view of C.S.S. Virginia (above) and C.S.S. Richmond (below), showing on Virginia the different layers of the model, grouped by color.

![]()

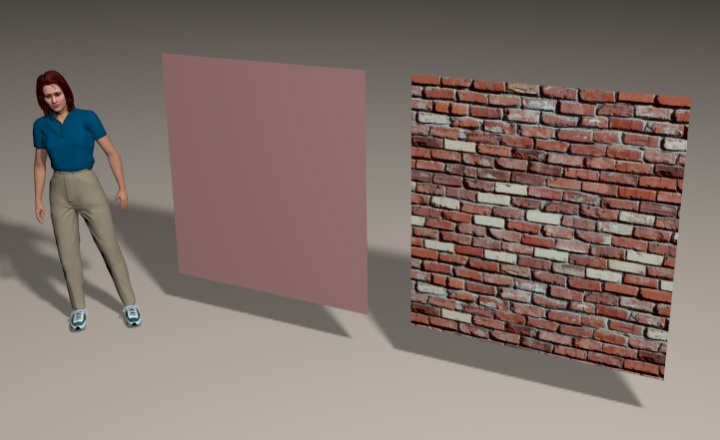

I also use a lot of ancillary software that are critical. I occasionally use Poser for figures (human or animal), and Photoshop constantly for developing textures and well as “post-production” work on the rendered model. Texture are images files (usually JPGs) that are projected onto the model to give it color and, um, texture. Applying a good texture – in this case, a photo of a brick wall — will make a simple plane into a substantial piece of masonry:

![]()

Two simple planes, the one on the right textured as a brick wall.

Two simple planes, the one on the right textured as a brick wall.

![]()

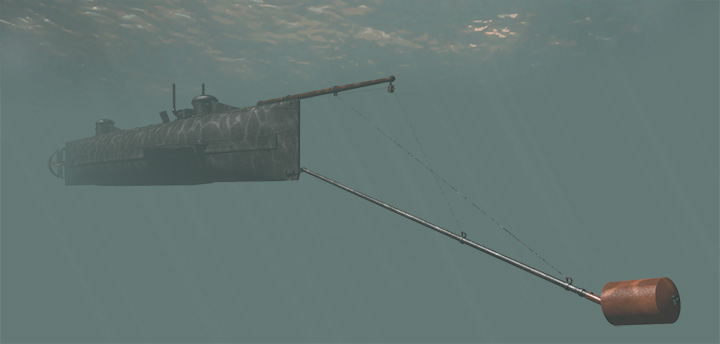

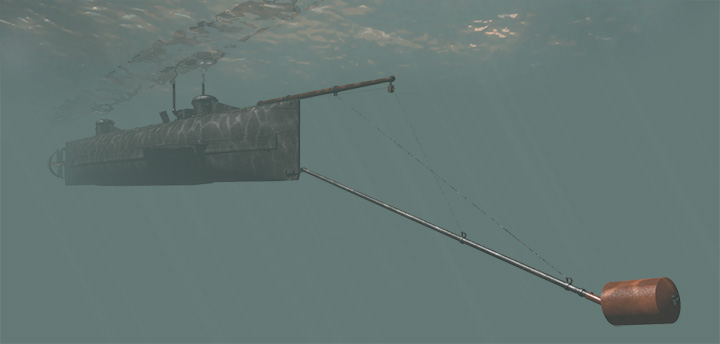

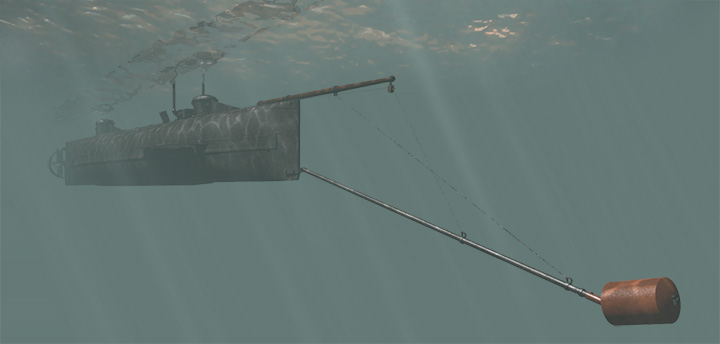

Finally, some images get a lot of “post” work after rendering, usually in Photoshop, to add elements that either the rendering software can’t do, or I don’t know how to do. For example, here’s a sequence with the Hunley model that takes it from an aseptic, obviously-a-model environment, and builds around it something that hopefully presents a more realistic depiction of how the boat might have appeared in real life:

1. Background color.

1. Background color.

2. Added light from surface.

2. Added light from surface.

3. Added light shafts for image background.

3. Added light shafts for image background.

4. Added rendered model of boat and spar torpedo.

4. Added rendered model of boat and spar torpedo.

5. Added reflection of boat on underside of water surface.

5. Added reflection of boat on underside of water surface.

6. Added light shafts in foreground, and the image is done.

6. Added light shafts in foreground, and the image is done.

![]()

Digital modeling has some advantages over building a physical model. Repetitive details (e.g., cannons or rail stanchions) can be exactly duplicated, over and over again, almost instantly. And if changes are needed, those can be accomplished much more readily with a digital model than a physical one. One reason I wanted to do Harlan is because she was of the same design as U.S.S. Hatteras, that I modeled some months ago; the Harlan digital model is currently being revised into a new and (I believe) more accurate rendering of Hatteras.

![]()

The updated Hatteras model.

![]()

Even so, digital models still lack the real beauty and style of a well-done physical model. It’s an aesthetic consideration, but it makes all the difference in the world. So now, go look at some real steamboat models by a real artisan, Rex Stewart.

___________

Lee, Pickett, and Mosby

Over the last couple of days, this post has received an unusual number of hits. I suspect this is due to Fort Pickett being in the news as it’s renamed as Fort Barfoot, and folks are doing web searches for George Pickett.

In any event, this seems like a good excuse to revisit this post from 2019.

Dead Confederates, A Civil War Era Blog

In 1870, not long before Robert E. Lee’s death, John Singleton Mosby visited him while both happened to be in Richmond. Mosby recalled accompanying George Pickett when the latter wanted to call on Lee, but didn’t want to do so alone:

_____________

I met General Lee a few times after the war, but the days of strife were never mentioned. I remember the last words he spoke to me about two months before his death at a reception that was given to him in Alexandria. When I bade him good-by, he said: “Colonel, I hope we shall have no more wars.”

In March 1870, I was walking across the bridge that connected the Ballard and Exchange Hotels in Richmond and, to my surprise, I met General Lee and his daughter. The general was pale and haggard, and did not look like the Apollo I had known in the army…

View original post 280 more words

“He has always voted with the Democrats.”

I’ve discussed in previous posts how, when one digs a little into the stories of old African American men who attended Confederate reunions, there’s often a subtext that tells as much about the how the men were perceived at the time of the reunion as it does about their role during the war. What does this item, from the Columbia, South Carolina State newspaper from April 26, 1910, tell readers about Mr. Harper’s wartime status? What distinctions does the paper draw (or imply) between Mr. Harper and the “old soldiers?” What does it say, that this is a news item in 1910? More important, what does it suggest about how he was viewed by white Confederate veterans in 1910?

Lawsuit Filed Over Arlington Confederate Monument

West face of the Confederate Monument at Arlington National Cemetery, photographed in September 2011 by Wikimedia user Tim1965. Reproduced here under Creative Commons license.

Some of you will recall that last year the Department of Defense published a report by the Congressionally-established Naming Commission that recommended changing the names of old Confederates from military installations (e.g., Fort Hood in Texas, and Fort Bragg in North Carolina), and removing Confederate iconography in various places. Another recommendation of the Naming Commission was to remove the Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery, sometimes referred to as the Reconciliation Monument. I’ve written about that monument before, and its supposed proof of the existence of Black Confederate soldiers. (Spoiler: it’s not.) The Naming Commission’s recommendation was that “the statue atop of the monument should be removed. All bronze elements on the monument should be deconstructed, and removed, preferably leaving the granite base and foundation in place to minimize risk of inadvertent disturbance of graves” (pp. 15-16).

Now comes a coalition of Confederate Heritage™ groups and individuals, led by a group from Florida called Defend Arlington, seeking to block any removal of alteration to the monument. You can read Defend Arlington’s initial filing here.

While I’m not an attorney, I’ve followed a number of these cases over the last few years, and there really doesn’t seem to be much new here, nor any compelling arguments made. The plaintiffs include some familiar names, and I honestly chuckled a little at the ways in which they claim they will be injured if the monument is removed. For some of them it seems quite a stretch.

Confederate activist H.K. Edgerton at an event in Pensacola, Florida in 2020. Photo by John Blackie via Pensacola News Journal.

Plaintiff Harold K. Edgerton is an individual residing in North Carolina. Plaintiff Edgerton is a Confederate Southern American of African ancestry. As an active and vocal defender of Southern culture and history and the honor of the Confederate soldier both black and white, Plaintiff Edgerton is often invited to speak on these issues in front of the Memorial, including the upcoming June 4 memorial service at ANC [Arlington National Cemetery]. He identifies with the African-American images on the Memorial and believes that its removal erases his black family’s participation in the Confederate struggle for independence from America’s most prominent military history museum.

I’m not aware that Edgerton has ever spoken at Arlington National Cemetery, so maybe the phrasing that he “is often invited to speak” there was chosen deliberately.

Edgerton and the attorney who drafted this filing – more about him anon – perhaps also should not have chosen to describe Edgerton as a “Confederate Southern American,” given that Edgerton’s patron and mentor, the odious Kirk Lyons, got sanctioned by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia to the tune of $10,000 for filing a discrimination action on behalf of some “Southern Confederate American” employees of DuPont, that the court found to be “not only incredible but, frankly, disingenuous. . . [and] also frivolous, unreasonable, and without foundation.”

But back to the plaintiffs.

Plaintiff Richard A. Moomaw is an individual residing in Virginia. Plaintiff Moomaw has ancestors buried in Section 16 of the ANC. Plaintiff Moomaw travels to Arlington with his family to honor those familial descendants that honorably served in our military. The Memorial represents the reunification of the North and South and the commemoration of all fallen military. Removal of the Reconciliation Memorial, as it is commonly known by, attributes a stigma of dishonor and disgrace to those soldiers, including Plaintiff’s descendants causing grave harm.

I don’t think this is gonna fly. Even if you stipulate that removal of the monument “attributes a stigma of dishonor and disgrace to those soldiers,” it’s pretty hard to argue that that opprobrium extends mysteriously down through the generations to someone in 2023 who never met his Confederate ancestor, or likely any other actual Confederate. (Private Samuel Moomaw of Ashby’s Seventh Virginia Cavalry, died in 1863.)

Plaintiff Edwin L. Kennedy, Jr. is an individual residing in Alabama. Plaintiff Kennedy has ancestors buried in unknown graves across the South and believes that the Memorial commemorates and marks the graves of his ancestors, in a manner similar to the Tomb of the Unknown Solder [sic.]. Removal of the Memorial will cause him grave harm.

You will never convince me that that last line isn’t a deliberate pun.

Anyway, Mr. Kennedy’s feelings are hurt, which somehow translates to “grave harm.” I will note that his home in New Market, Alabama is nearly 600 miles away from the monument at Arlington, and there’s no indication in the filing that Mr. Kennedy has ever visited the national cemetery there. This reminds me a bit of the situation with Hiram Patterson of Dallas, who was talked into being plaintiff in a lawsuit over the Robert E. Lee monument in Dallas, who never read the claim before it was filed, had never heard of the attorney filing the case before the day it was filed, and admitted to being uncertain of what the legal claim being made in his name was.

Plaintiff Teresa E. Roane is an individual residing in Virginia. Plaintiff Roane is a past Archivist for the Museum of the Confederacy and has given speeches in front of the Memorial. Plaintiff Roane has been invited to speak at the Memorial on June 4, 2023. Removal will negatively impact Plaintiff Roane’s economic opportunities associated with historic and civil war tour guide opportunities.

As with Edgerton, I’m not sure Ms. Roane has made any formal address at the monument, but perhaps so. This is the only plaintiff’s description I see that specifies the sorts of injuries that are usually at the heart of a civil lawsuit, in this case making it more difficult for her to work guiding tours there. Maybe those presentations as a tour guide are the “speeches in front of the Memorial” described in the filing.

The plaintiffs are represented by attorneys from the Washington D.C. offices of Lewis Brisbois Bisgaard & Smith, one component of a very large, nationwide firm. The lead attorney seems to be Paul Kisslinger, a partner in the D.C. office, and until recently was the Assistant Chief Litigation Counsel for the Enforcement Division of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Kisslinger is obviously a very skilled and experienced attorney, but I really feel like this case is a dog, and pretty far afield from his specialty practice area.

While I’m not an attorney, I’ve followed a number of these cases over the last decade, and this one really seems like a new verse to a tired, old tune. (The plaintiffs go to a lot of trouble in the filing to assert that they’re striving hard for diversity, mentioning not less than FOUR TIMES that the monument’s sculptor, Moses Ezekiel, was Jewish.) More often than not, it seems to me, these cases get dismissed before ever going to trial, usually because the plaintiffs lack standing – that is, they are in a position that they will suffer real, concrete, and measurable harm without intervention by the courts. I’m just not seeing that here, and only one of the plaintiffs, Teresa Roane, even hints at it. But her argument – that she will suffer economic damage through harm to her Civil War tour business – seems pretty weak, given that the Confederate burials themselves will not be moved, and the granite base of the monument would remain in place under the recommendations of the Naming Commission.

So we’ll see what happens. I’ve been wrong before in predicting how the courts would go, so I’m not going to bet major money on this one. But I will be surprised if the plaintiffs prevail.

Stay tuned, y’all.

Frederick Douglass on Decoration Day, 1871

On Decoration Day, 1871, Frederick Douglass gave the following address at the monument to the Unknown Dead of the Civil War at Arlington National Cemetery. It is a short speech, but one of the best of its type I’ve ever encountered. I’ve posted it before, but it think it’s something worth re-reading and contemplating every Memorial Day.

The Unknown Loyal Dead

Arlington National Cemetery, Virginia, on Decoration Day, May 30, 1871Friends and Fellow Citizens:

Tarry here for a moment. My words shall be few and simple. The solemn rites of this hour and place call for no lengthened speech. There is, in the very air of this resting-ground of the unknown dead a silent, subtle and all-pervading eloquence, far more touching, impressive, and thrilling than living lips have ever uttered. Into the measureless depths of every loyal soul it is now whispering lessons of all that is precious, priceless, holiest, and most enduring in human existence.

Dark and sad will be the hour to this nation when it forgets to pay grateful homage to its greatest benefactors. The offering we bring to-day is due alike to the patriot soldiers dead and their noble comrades who still live; for, whether living or dead, whether in time or eternity, the loyal soldiers who imperiled all for country and freedom are one and inseparable.

Those unknown heroes whose whitened bones have been piously gathered here, and whose green graves we now strew with sweet and beautiful flowers, choice emblems alike of pure hearts and brave spirits, reached, in their glorious career that last highest point of nobleness beyond which human power cannot go. They died for their country.

No loftier tribute can be paid to the most illustrious of all the benefactors of mankind than we pay to these unrecognized soldiers when we write above their graves this shining epitaph.

When the dark and vengeful spirit of slavery, always ambitious, preferring to rule in hell than to serve in heaven, fired the Southern heart and stirred all the malign elements of discord, when our great Republic, the hope of freedom and self-government throughout the world, had reached the point of supreme peril, when the Union of these states was torn and rent asunder at the center, and the armies of a gigantic rebellion came forth with broad blades and bloody hands to destroy the very foundations of American society, the unknown braves who flung themselves into the yawning chasm, where cannon roared and bullets whistled, fought and fell. They died for their country.

We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.

I am no minister of malice. I would not strike the fallen. I would not repel the repentant; but may my “right hand forget her cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth,” if I forget the difference between the parties to hat terrible, protracted, and bloody conflict.

If we ought to forget a war which has filled our land with widows and orphans; which has made stumps of men of the very flower of our youth; which has sent them on the journey of life armless, legless, maimed and mutilated; which has piled up a debt heavier than a mountain of gold, swept uncounted thousands of men into bloody graves and planted agony at a million hearthstones — I say, if this war is to be forgotten, I ask, in the name of all things sacred, what shall men remember?

The essence and significance of our devotions here to-day are not to be found in the fact that the men whose remains fill these graves were brave in battle. If we met simply to show our sense of bravery, we should find enough on both sides to kindle admiration. In the raging storm of fire and blood, in the fierce torrent of shot and shell, of sword and bayonet, whether on foot or on horse, unflinching courage marked the rebel not less than the loyal soldier.

But we are not here to applaud manly courage, save as it has been displayed in a noble cause. We must never forget that victory to the rebellion meant death to the republic. We must never forget that the loyal soldiers who rest beneath this sod flung themselves between the nation and the nation’s destroyers. If today we have a country not boiling in an agony of blood, like France, if now we have a united country, no longer cursed by the hell-black system of human bondage, if the American name is no longer a by-word and a hissing to a mocking earth, if the star-spangled banner floats only over free American citizens in every quarter of the land, and our country has before it a long and glorious career of justice, liberty, and civilization, we are indebted to the unselfish devotion of the noble army who rest in these honored graves all around us.

______________

Image: Graves of nine unknown Federal soldiers in Pontotoc County, Mississippi. Photo by Flickr user NatalieMaynor, used under Creative Commons license. Text of Douglass speech from Philip S. Foner and Yuval Taylor, Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings.

Decoration Day at Arlington, 1871

As many readers will know, the practice of setting aside a specific day to honor fallen soldiers sprung up spontaneously across the country, North and South, in the years following the Civil War. One of the earliest — perhaps the earliest — of these events was the ceremony held on May 1, 1865 in newly-occupied Charleston, South Carolina, by that community’s African American population, honoring the Union prisoners buried at the site of the city’s old fairgrounds and racecourse, as described in David Blight’s Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory.

Over the years, “Decoration Day” events gradually coalesced around late May, particularly after 1868, when General John A. Logan, commander-in-chief of the Grand Army of the Republic, called for a day of remembrance on May 30 of that year. It was a date chosen specifically not to coincide with the anniversary of any major action of the war, to be an occasion in its own right. While Memorial Day is now observed nationwide, parallel observances throughout the South honor the Confederate dead, and still hold official or semi-official recognition by the former states of the Confederacy.

Recently while researching the life of a particular Union soldier, I came across a story from a black newspaper, the New Orleans Semi-Weekly Louisianan dated June 15, 1871. It describes an event that occurred at the then-newly-established Arlington National Cemetery. Like the U.S. Colored Troops who’d been denied a place in the grand victory parade in Washington in May 1865, the black veterans discovered that segregation and exclusion within the military continued even after death:

DECORATION DAY AND HYPOCRISY.

The custom of decorating the graves of soldiers who fell in the late war, seems to be doing more harm to the living than it does to honor the dead. In every Southern State there are not only separate localities where the respective defendants of Unionism and Secession lie buried, but there are different days of observance, a rivalry in the ostentatious parade for floral wealth and variety, and a competition in extravagant eulogy, more calculated to inflame the passions than to soften and purify the affections, which ought to be the result of all funeral rights.

Besides this bad effect among the whites there comes a still more evil influence from the dastardly discriminations made by the professedly union [sic.] people themselves.

Read this extract from the Washington Chronicle:

AT THE COLORED CEMETERY

While services were in progress at the tomb of the “Unknown” Comrade Charles Guthridge, John S. Brent, and Beverly Tucker, of Thomas R. Hawkins Post, No. 14 G.A.R., followed by Greene’s Brass Band, Colonel Perry Carson’s Pioneer Corps of the 17th District, Butler Zouaves, under the command of Charles B. Fisher, and a large number of colored persons proceeded to the cemetery on the colored soldiers to the north of the mansion, and on arriving there they found no stand erected, no orator or speaker selected, not a single flag placed on high, not even a paper flag at the head boards of these loyal but ignored dead, not even a drop of water to quench the thirst of the humble patriots after their toilsome march from the beautifully decorated grand stand above to this barren neglected spot below. At 2 ½ o’clock P.M., no flowers or other articles coming for decorative purposes, messengers were dispatched to the officers of the day for them; they in time returned with a half dozen (perhaps more) rosettes, and a basket of flower leaves. Deep was the indignation and disappointment of the people. A volley of musketry was fired over the graves by Col. Fisher’s company. An indignation meeting was improvised, Col. Fisher acting president. A short but eloquent address was made by George Hatton, who was followed by F. G. Barbadoes, who concluded his remarks by offering the followign resolutions, which were unanimously adopted:

Resolved, that the colored citizens of the District of Columbia hereby respectfully request the proper authorities to remove the remains of all loyal soldiers now interred at the north end of the Arlington cemetery, among paupers and rebels, to the main body of the grounds at the earliest possible moment.

Resolved, that the following named gentlemen are hereby created a committee to proffer our request and to take such further action in the matter as may be deemed necessary to a successful accomplishment of our wishes: Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston, Rev. Dr. Anderson, William J. Wilson, Col. Charles B. Fisher, William Wormley, Perry Carson, Dr. A. T. Augusta, F. G. Barbadoes.

If any event in the whole history of our connection with the late war embodied more features of disgraceful neglect, or exhibited more clearly the necessity of protecting ourselves from insult, than this behavior at Arlington heights, we at least acknowledge ignorance of it.

We say again that no good, but only harm can result from keeping up the recollection of the bitter strife and bloodshed between North and South, and worse still, in furnishing occasion to white Unionists of proving their hypocrisy towards the negro in the very presence of our dead.

The black soldiers’ graves were never moved; rather, the boundaries of Arlington were gradually expanded to encompass them, in what is now known as Section 27. Most of the graves, originally marked with simple wooden boards, were subsequently marked with proper headstones, though many are listed as “unknown.” In addition to the black Union soldiers interred there, roughly 3,800 civilians, mostly freedmen, lie there as well, many under stones with the simple, but profoundly important, designation of “citizen.” The remains of Confederate prisoners buried there were removed in the early 1900s to a new plot on the western edge of the cemetery complex, where the Confederate Monument would be dedicated in 1914.

Unfortunately, the more things change, the more. . . well, you know. In part because that segment of the cemetery began as a burial ground for blacks, prisoners and others of lesser status, the records for Section 27 are fragmentary. Further, Section 27 has — whether by design or happenstance — suffered an alarming amount of negligence and lack of attention over the years. The Army has promised, and continues to promise, that these problems will be corrected.

As Americans, North and South, we should all expect nothing less.

____________________________________

Images of Section 27, Arlington National Cemetery, © Scott Holter, all rights reserved. Used with permission. Thanks to Coatesian commenter KewHall (no relation) for the research tip.

Three Veterans

Note: This is the first of three posts that I republish every Memorial Day weekend. Last week I was traveling, and so was unable to post them over several days as I usually do.

_______

This Memorial Day weekend, I’d like to highlight three Civil War veterans interred here in Galveston. I don’t have a familial or personal connection to any of them, but I think of them as neighbors of mine, of a sort.

Charles DeWitt Anderson (1827-1901) served as a Colonel in the Confederate army, and in the summer of 1864 was charged with the defense of Fort Gaines, on the eastern side of the entrance to Mobile Bay. After Admiral Farragut forced the entrance to Mobile Bay on August 4, Anderson found himself entirely cut off, besieged and under artillery fire from the land side of Dauphin Island and unable to have any effect on the Federal fleet, which had moved farther up Mobile Bay, out of range of Fort Gaines’ guns. Faced with demoralized Confederate troops inside the fort, Anderson surrendered on August 8. Given a choice of surrendering to the U.S. Army or Navy, Anderson turned over his sword to Farragut. One of Farragut’s last acts before he died in 1870 was to request that Anderson’s sword be returned to him. It came back to Anderson with the inscription, “Returned to Colonel C. D. Anderson by Admiral Farragut for his Gallant Defence of Fort Gaines, April 8, 1864.”

What fewer people know about Anderson is that he and his younger brother arrived in Texas as orphans, their parents having died on the ship en route to the Republic of Texas in 1839. They were adopted right there on the wharf by an Episcopal minster. In 1846, Anderson was the first cadet admitted to West Point from the newly-established State of Texas; his application letter was endorsed by U.S. Senator Sam Houston. Although Anderson did not graduate from the Point, he eventually received a direct commission into the Fourth U.S. Artillery in 1856, and served until resigning his commission in 1861. Anderson served longer as a U.S. Army officer than as a Confederate one; you can view a detail of an 1859 map drawn by Anderson of the area around Fort Randall, Dakota Territory, here.

In his postwar years he worked as an engineer on a variety of public works projects, and at the time of his death was serving as the keeper of the Fort Point Lighthouse here. William Thiesen, the Atlantic Area Historian for the U.S. Coast Guard, recently wrote about Anderson’s experience at Fort Point during the 1900 Storm, the deadliest natural disaster in U.S. history. Recall that, at the time, Anderson was in his seventies:

True to his mission, Anderson kept the light burning during the storm even though most ships by then were either adrift, out of control or washing ashore at points along the Texas coast. However, late that evening, floodwaters surged and carried off equipment on the lighthouse’s lower deck, including the lifeboat and storage tanks for fresh water and kerosene fuel. With seawater rising into the keeper’s quarters it seemed as if Fort Point Lighthouse was adrift on a stormy sea. With the wind speeds nearing 200 miles per hour, the lighthouse’s heavy slate roof began to peel away. Eventually, some of the flying stone tiles shattered the lantern room windows and the inrushing wind snuffed out the light for good.

Anderson had tried his best to maintain the light, but the flying glass had lacerated his face and driven him below. By late that evening, the quarters’ first floor had flooded, the wind had permanently extinguished the light, Keeper Anderson suffered from facial wounds and the storm surge had trapped the elderly couple on the second floor. With all hope lost, Anderson and wife Lucy made their way to the second floor parlor room, sat down and waited in silence for the floodwaters to take them away.

But the end never came. On Sunday morning, the Andersons emerged arm-in-arm onto the lighthouse gallery to see the human toll of the hurricane. The scene they witnessed beggars description. In a silent watery funeral procession, the ebbing tide carried away countless bodies from Galveston Bay to the Gulf of Mexico. Anderson likely saw as much carnage, if not more, than at any time during his Civil War career. But, unlike the war, the storm did not favor one victim over another; instead, it took the lives of women and children as well as men.

____

George Frank Robie (1844-91) was a Sergeant in Company D of the Seventh New Hampshire Volunteer Infantry, who won the Medal of Honor “for gallantry on skirmish line” during fighting around Richmond, Virginia in September 1864.

Robie originally enrolled in the Eighth Massachusetts Militia, a three-month unit, the day after the surrender of Fort Sumter in 1861. His service record gives his age at enlistment as 18, but other sources suggest he was a year younger. After being discharged, he enlisted in the Seventh New Hampshire in September 1861 as a Sergeant. He re-enlisted in the regiment in February 1864, and was appointed First Lieutenant in October. Although Robie was recommended for a medal during the war, his Medal of Honor, like many, was not actually awarded until June 1883 by resolution of Congress.

He moved to Galveston after the war, working as a clerk in a railroad office, but suffered from rheumatism that had first afflicted him during his service in Virginia. Robie returned to New England, and in 1884 was awarded a pension for disability. Robie subsequently returned to Galveston, dying here in 1891. To my knowledge, Robie is the only Civil War Medal of Honor winner interred in Galveston County. The Fitts Museum in Candia, New Hampshire, where Robie was born, holds Robie’s sword in its collection.

____

Josiah Haynes Armstrong (1842-98) was a Sergeant in the Third U.S. Colored Infantry. He was born free in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, enlisted as a Corporal on June 26, 1863 at Philadelphia, and soon thereafter was promoted to Sergeant. The Third U.S.C.I. spent the latter part of the war in the Jacksonville, Florida, area, although Armstrong became ill and was transferred to a military hospital in St. Augustine. Some time later, his company commander, who had heard that Armstrong was convalescent and working at the hospital as a cook, wrote to request that he be sent back to the regiment, as he would “be obliged to make another Sergt in [Armstrong’s] place, which, as he is an excellent non-com officer, I am loathe to do.”

After his discharge, Armstrong remained in Florida, where he became a member of the clergy in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. He also served in the Florida State House of Representatives, representing Columbia County, in 1871, 1872, and 1875. He moved to Galveston in 1880, where he was pastor of Reedy A.M.E. Chapel here. Armstrong also served as Grand Master of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Texas, the African American branch of American freemasonry, from 1890 to 1892. He was ordained a Bishop in the A.M.E. Church in 1896, two years before his death at age 56.

_____

Anderson photo courtesy Col. Anderson’s great-grandson, Dale Anderson, and Bruce S. Allardice.

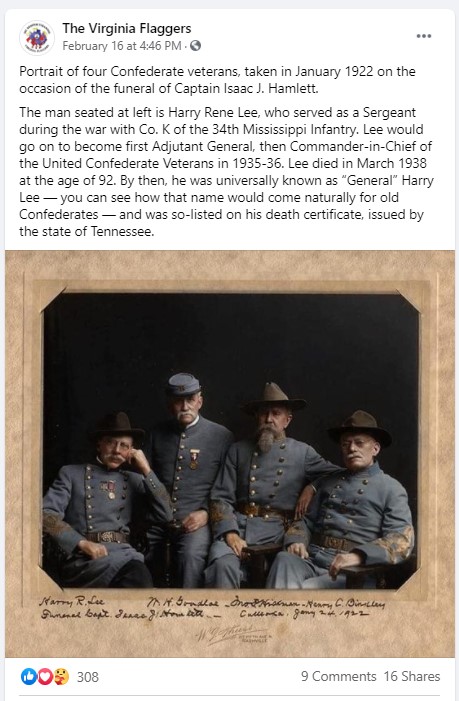

The Copy-and-Paste Confederacy

The Virginia Flaggers may not be my biggest fans, but they clearly think my efforts are good enough to plagiarize this old 2013 post of mine. Virtually every word in their Facebook posting is one I wrote eight years ago, verbatim. The only important thing they omitted was the name of the artist who colorized the original black-and-white image, Mads Madsen, and that’s actually a bigger offense.

The Flaggers claim to stand for “Honor, Dignity, Respect, and Heritage,” but those things apparently don’t prevent them from taking others’ work and passing it off as their own. The Confederate Heritage™ movement has always done this, of course, so I shouldn’t be surprised.

_____

Well. . .Bye.

Update, March 1: It turns out that Bill Dorris’ estate is worth far less than one might expect, given his bequest of $5 million to his dog, who didn’t even live with him. Like, maybe ONE TENTH of that.

What a BS artist that guy was. Thanks to KEW for bringing this to my attention.

_____

Charles William “Bill” Dorris (above), the Nashville attorney and developer who owned the land on Interstate 65 where that hideous fiberglass statue of Nathan Bedford Forrest stands, carked late last year. Dorris insisted he wasn’t racist, of course, but in 2015 he told Nashville Public Radio that the institution of slavery has been badly maligned, as it was a form of “social security” for African Americans. Dorris remained a self-indulgent asshole to the end, leaving $5 million in his will to his 8-year-old border collie, who didn’t even live with him. The dog will continue living with its long-time caretaker, Martha Burton, who I hope at least gets to benefit materially from every dime in that dog’s trust.

The rest of Dorris’ large estate is currently in probate court, that will decide the fate of the Interstate 65 property and the Forrest statue. The statue itself was created by Dorris’ friend, the unrepentant white nationalist and segregationist Jack Kershaw, who died and went to Hell in 2010.

_______

Photo by Shelley Mays of the Nashville Tennessean.

“There stands Jackson. . . wait, where’d he go?”

Stonewall Jackson no longer glowers across the parade ground at the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington.

H/t Kevin. Photo by Steve Helber, Martinsville Journal.

_____

leave a comment