Henry Martyn Stringfellow: A Soldier’s Story

On Thursday evening I had the privilege of speaking at Stringfellow Orchards in Hitchcock, on the early life and Civil War military service of Henry Stringfellow. It’s a story that I don’t think has been told before in any detail, and it was made better by the fact that I got to tell it on Stringfellow’s front porch — literally. The site’s current owner, or steward, as he sometimes refers to himself, is Sam Collins III, who has taken a great interest Hitchcock’s history and the central place Stringfellow’s Orchard had in its early development.

Stringfellow is an interesting character, as you will see. He was born into a prominent family of Virginia clergymen, and was himself well along that career path himself when the war came. Within eighteen months of enlisting in the local artillery battery, the Hanover Artillery, Stringfellow was commissioned a lieutenant and assigned to the staff of John Bankhead Magruder’s new command in Texas. It was a move that changed the entire course of his life. After seeing action in the Battle of Galveston on New Year’s Day 1863, Stringfellow married a Texas girl, Alice Johnston, from Seguin. Henry and Alice decided to make their postwar homes in Texas, where Henry soon found himself wrapped up in horticulture. Stringfellow proved to be both a successful and unconventional grower, attracting much acclaim in the last decades of the 19th century. Stringfellow was almost as unconventional with people as he was with plants; he reportedly earned the enmity of other growers in the area by paying his African American orchard workers a dollar a day, when the local custom was to pay fifty cents. That’s not necessarily what one might expect from a man whose grand-uncle wrote one of the most widely-circulated tracts asserting the Christian righteousness of chattel bondage of the antebellum period.

But, I’m get ahead of the story. Sam will be giving a presentation on Stringfellow’s later life at the orchard on April 23. For now, here’s my profile of Henry Martyn Stringfellow.

Henry Martyn Stringfellow was born at Winchester, Virginia on January 21, 1837. Henry was the seventh child, and fifth son, of the Reverend Horace Stringfellow and his first wife, Harriett Strother Stringfellow. Horace and Harriett Stringfellow had a total of ten children prior to her death in 1847; Horace Stringfellow subsequently married a woman named Camilla Harris, with whom he had three more children. [1]

Horace Stringfellow was a prominent member of the Episcopal clergy in Virginia in the decades before the Civil War. Horace had originally trained as an attorney, but in his mid-thirties gave up the practice of law and went into the Virginia Seminary. After his ordination in 1835, he became rector of Trinity Church in Washington, D.C. In 1847 he became rector of St. Paul’s Church in Petersburg, Virginia, one of the more prominent Episcopalian dioceses in the state, and served there until 1854, when he moved to St. Martin’s Parish in Hanover County, just north of Richmond. Rev. Stringfellow remained at St. Martin’s through the war years until his retirement from the active ministry in 1866. [2]

We can make some inferences about Henry’s childhood from the historical record. He lived in a large (and ever-growing) household. The Stringfellows had a comfortable lifestyle; Rev. Stringfellow reported owning about $5,000 worth of real estate at the time of the 1850 U.S. census, and the same amount again in 1860. In 1860, on the eve of the Civil War, Rev. Stringfellow also reported assets of $20,000 in personal property. Rev. Stringfellow was a slaveholder. In 1860 he owned eleven slaves – four adults, two men and two women, ranging in age from 25 to 60, and seven children, ranging in age from six months to twelve years. In keeping with the practice at the time, their names were not recorded in the census.

We can know that, within the large, bustling household, mortality was very real. Of Rev. Stringfellow’s ten children with Harriet, four died before reaching adulthood. Harriet herself died in July 1847, just four months after the birth of her youngest daughter, Agnes. Henry was ten when his mother died. This almost continual experience with death must have had a profound effect on young Henry, and may have helped shape his own interest in the afterlife that came about after the death of his own beloved son, Leslie, decades later.

Not surprisingly, education was highly valued for members of the Stringfellow household. Henry was sent off to school at the College of William and Mary, from which he graduated in 1858 at the age of twenty-one. Perhaps intended to follow in his father’s footsteps, Henry entered the Virginia Theological Seminary at Alexandria in 1859, graduating with a degree in the spring of 1861, just as tensions over the future of slavery brought about secession and open war between the newly-organized Confederate States and the national government in Washington. [3]

Rev. Stringfellow’s views on secession and slavery are not entirely clear, but other members of the extended Stringfellow family were more outspoken. Horace Stringfellow’s uncle, the Rev. Thornton Stringfellow of Culpepper, Virginia, published a volume in 1856, arguing that chattel bondage was not only permitted by Holy Scripture, but was a positive blessing on those actually enslaved. This was, in fact, a common view among slaveholders, who found a way to rationalize the peculiar institution as reflecting God’s will, and condemning the agitation of abolitionists who would interfere with it. Robert E. Lee believed much the same thing, himself. Another distant relative, James L. Stringfellow of Culpepper County, was active in local Democratic politics and, after John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry, set about organizing militia companies that would ultimately form the core of state troops that the Commonwealth of Virginia would put into the field in the first months of the war.

Closer to home, Rev. Horace Stringfellow’s own sons found themselvesembroiled in the conflict. The eldest surviving son, Horace Stringfellow, Jr., was rector of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Indianapolis, was widely suspected of having southern sympathies, particularly after having argued better conditions for Confederate prisoners held at nearby Camp Morton. St. Paul’s in Indianapolis became known by local wags as the Church of the Holy Copperheads, Holy Rebellion, or St. Butternut, and Stringfellow was forced to step down as rector in June 1862. [4]

Charles Simeon Stringfellow, just a year older than Henry, was commissioned into the Confederate army as an Assistant Adjutant General, and ended the war with the rank of major. Another brother, James Wade Stringfellow, served as an officer in a Louisiana regiment and was wounded at the Battle of Shiloh in 1862.

Henry Martyn Stringfellow, age 24, enlisted in his home county unit, the Hanover Artillery, on May 21, 1861. At the time of his enlistment he was described as being five feet ten inches tall, with gray eyes and dark hair. Like most recruits at this time, he enlisted for a period of one year. The Hanover Artillery, which was eventually rolled into the 31st Battalion of Virginia Light Artillery, saw relatively little action during its first year of existence. It was, however, actively engaged in July 1, 1862 at the Battle of Malvern Hill, during the Seven Days Battles. Malvern Hill was a defeat for the Confederate, who lost about 5,600 men, killed, wounded and captured, versus about 3,000 for the Federals. Confederate casualties were particularly high as a result of repeated frontal assaults, late in the day, on dug-in Union troops by the division under the command of Major General John Bankhead Magruder. [5]

There is one very unusual element in Stringfellow’s military career in this period. According to his obituary published in Confederate Veteran magazine in 1912, Stringfellow had particular skill as a draftsman, and in the winter of 1861-62 helped prepare the drawings used in the construction of the Confederate casemate ironclad Virginia, or as it’s more commonly known, Merrimack. [6] The ship was completed in early March 1862, and on March 8 attacked the Federal squadron at Hampton Roads, Virginia. She destroyed two wooden warships, Cumberland and Congress, with only minor damage to herself. The next evening the new Union ironclad Monitor arrived. The two ships fought to a draw the following day, but the Union scored a strategic victory because Virginia never challenged the U.S. fleet there again, and was eventually blown up by her own crew. The battle between Virginia and Monitor is one of the most famous in naval history, and marks the beginning of a new era in naval technology, that of armored ships and shell-firing guns. I haven’t been able to verify Stringfellow’s involvement in that story, but it would be interesting to think that he played a small role in bring it about.

In the fall of 1862, the Union navy captured Galveston, essentially without firing a shot. The Confederate commander who had failed to effectively defend Galveston was sacked, and Major General Magruder was appointed to replace him.

General Magruder brought with him several officers to serve as staff, to assist in reorganizing his new command. One of these men was Henry Stringfellow, whose assignment was formally requested by Magruder on October 16, 1862, with the rank of Lieutenant of Artillery. Unfortunately, we don’t know why Magruder wanted Stringfellow on his staff. Magruder was a Virginian, and likely knew (or at least knew of) members of the extended Stringfellow family. By military specialty, Magruder was an artillerist, and retained a special affinity for that branch of service, even when commanding larger units of combined arms. Other than these factors, though, we simply don’t know why Magruder chose Stringfellow to accompany him to Texas.

Stringfellow’s new orders were issued on October 18, 1862 – he was on his way to Texas. [7]

General Magruder’s first order of business after arriving in Texas was to recapture Galveston before it could be fully occupied by Union troops, and used as a staging place for a larger invasion of Texas. Magruder and his staff spent several weeks developing a plan by which Union forces on the island would be attacked simultaneously by infantry on shore, and by Confederate gunboats in the harbor. It was an audacious plan, with lots of moving parts that all had to work in unison if the thing was going to work.

During this planning period, Stringfellow’s primary duties as a staff ordnance officer would be to locate, inspect and collect all the artillery in the region that could be used in the attack on Galveston. In addition to the guns themselves, he would be responsible for their carriages, limbers, ammunition wagons and ammunition, mules of horses to haul the guns, tack and harness, and so on. It would have been a daunting task, one that required thoroughness and careful attention to detail. In all, Magruder and Stringfellow managed to round up twenty-one guns to be used in the land assault — six pieces of siege artillery, fourteen field pieces and a gun mounted on a flat rail car, protected by bales of cotton.

Magruder launched his attack on the Federals at Galveston in the pre-dawn darkness of New Years Day, 1863. Magruder himself fired the first artillery piece, on 20th Street near the Hendley Building on the Strand, saying theatrically, “I have done my best as a private; I will go and attend to that of a general.” Confederate guns opened up all along the Galveston waterfront, firing on Federal ships in the harbor. As a staff officer, Lieutenant Stringfellow was not assigned to any particular battery, but was supposed to move between them, passing along instructions and relaying situation reports to Magruder.

At some point in the action – and we don’t know exactly where or when – an officer in charge of a nearby gun was struck, and Stringfellow took over. In his full report of the action, written several weeks later, Magruder mentioned this action by Stringfellow and other staff officers:

Lieutenants Stringfellow, Jones, and Hill, of the artillery, behaved with remarkable gallantry during the engagement, each of them volunteering to take charge of guns and personally directing the fire after the officers originally in charge of them had been wounded. [8]

In the end, the Confederates succeeded in retaking Galveston, but it had been a very near-run thing. Magruder, having made and won a huge gamble with his convoluted plan to recapture Galveston, was determined that it would remain in Confederate hands. He set about constructing a string of shore batteries along the Gulf front of the city, connected by rail and a miles-long series of trenches and earthworks. Slave laborers were impressed into service to do most of this work. During this period, Lieutenant Stringfellow would have been busily occupied in moving guns and all their attendant gear to various places along the coast, where defenses were being built up.

By the summer of 1863, however, Stringfellow’s service record indicates that he was spending considerable time in San Antonio, which was the military headquarters from the Confederate Western Subdistrict of Texas. San Antonio served as a supply and military depot for Confederate forces scattered around the western Texas frontier, much as it had for the U.S. Army in the years before the war. For the remainder of the war, it seems, Stringfellow divided his time mostly between Houston and San Antonio, serving as ordnance officer and military storekeeper at each place.

In November 1863, while stationed in San Antonio, Lieutenant Stringfellow wrote a letter to General Magruder, asking that he be promoted to Captain. Stringfellow pointed out that his service since coming to Texas had been exemplary, and that he had passed the examination for proportion to Captain. The officers who had come with him to Texas a year before had all received promotions, except Stringfellow. [9]

Stringfellow ultimately was promoted to Captain of Artillery, although I have not been able to confirm a date for that.

Lieutenant Stringfellow may have been anxious to secure a promotion – along the “the pay & emoluments thereof,” as he said in his letter to Magruder – because he was going to need the additional $30 per month in salary. [10] A few weeks after urging Margruder for promotion, Stringfellow married Alice Johnston of Seguin, Texas. He was twenty-six; she was eighteen. Alice was the daughter of Joseph R. Johnston, a wealthy physician from Sequin. How Henry and Alice came to meet is not known.

Over the next eighteen months, Stringfellow’s military life was probably relatively uneventful. And with Alice, it was probably happy, as well. He divided his time between the military depots at Houston and San Antonio, continuing to serve as a staff ordnance officer. It’s unclear whether Alice remained in Seguin with her family, or took up lodging in San Antonio or Houston.

The life of a Confederate staff officer like Henry Stringfellow in Texas, while it required long hours and many miles of travel over rutted roads, dusty in the summer and muddy in the winter, was not one of particular hardship. Most of Texas remained securely in Confederate hands through the conflict, and there were few foraging armies moving across the countryside, decimating livestock and crops. Compared to much of the rest of the Confederacy, basic foodstuff were relatively plentiful – although expensive — and there were few enemies anywhere nearby. Even fine consumer goods could be acquired in Houston, if one was willing to pay the exorbitant costs associated with luxuries run in through the Union blockade.

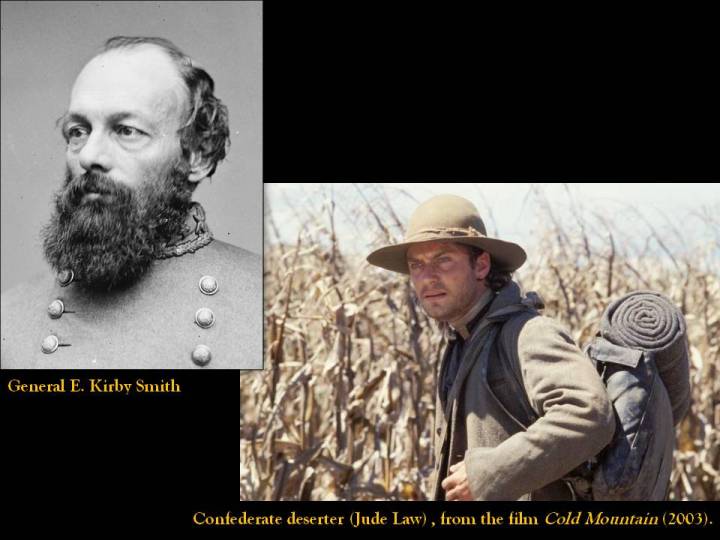

In the spring of 1865, however, the Trans-Mississippi Department – that part of the Confederacy west of the Mississippi River – began rapidly to unravel. Discouraged by Sherman’s advance across Georgia in late 1864, and north into the Carolinas in early 1865, and worried about their families left at home, Confederate troops in Texas began walking away from their units in large numbers. The problem increased substantially in April and May, when it became known that Confederate armies in the east had surrendered, and the Confederate capital at Richmond had fallen to union forces. Gangs of soldiers broke into military storehouses, looting them of provisions, hardware, and anything else they might use or sell for cash money. Senior officers tried to convince their men to remain in the ranks, but ultimately they were forced to bow to the inevitable. On June 2, 1865 – two months to the day after the evacuation of Richmond – General Magruder and the commander of the Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department, E. Kirby Smith, went out in a boat to one of the Union warships stationed on blockade duty off Galveston, and surrendered all Confederate forces west of the Mississippi. The war was over.

With the collapse of the Confederacy, and insufficient Federal troops yet in the state to maintain some sort of order, there was a great deal of chaos. Some senior Confederate officers, including Kirby Smith and Magruder, crossed the border into Mexico, to await further developments and to see if they could return without risking prosecution for their wartime activities. More junior officers, like Stringfellow, probably just laid low, pending further development. In this situation, Stringfellow was fortunate in having Alice’s family for support in the weeks following the collapse.

On the second Wednesday in August 1865, Captain Henry Martyn Stringfellow presented himself at the U.S. Provost Marshal’s office in Houston, and formally turned himself in as a prisoner of war. The Provost Marshal, Captain Michael McCaffrey of the 48th Ohio Vol. Infantry, filled out a pre-printed parole document with Stringfellow’s particulars, and had Henry sign it. [11] Thus ended Henry Martyn Stringfellow’s military career during the Civil War.

Henry and Alice settled in Galveston after the war, where he apparently lost much of what money he had on some ill-advised business ventures. The in the spring of 1866, sitting on the wharves fishing, Stringfellow struck up a conversation with an old man who explained how he’d grown wine grapes before the war, over on the Bolivar Peninsula. Stringfellow was fascinated, and began buying books on horticulture. Soon he and Alice established an orchard on the west side of town, and his career as grower was begun.

Henry Martyn Stringfellow is an interesting character in many ways. The son of a prominent Virginia family, seeming born to a life in the pulpit, the evident path of his life shifted dramatically when he came to Texas as a newly-commissioned Confederate officer. He earned high praise from his commanding officer for his conduct at the Battle of Galveston, but his military career was otherwise not especially noteworthy. He did his job as a staff officer, one that didn’t bring much in the way of glory or fame. And when the war ended, he and Alice made the best of their way, together. In so many ways, he’s typical of soldiers North and South — young men whose lives were interrupted by an all-consuming war, who volunteered to do their part as they saw it, and when it was over, embarked on entirely new lives that they probably had never imagined.

One final note about Henry Stringfellow. Sam originally asked me to do this talk a few months ago, and I readily agreed because it seemed like an interesting story, which it is. But only recently I realized that a relative of mine, my great-grand uncle Joseph Courtenay Ralston (1840-1924), undoubtedly knew Stringfellow personally. Ralston served during the latter part of the war as a staff officer and aide-de-camp to his own uncle, John George Walker, who commanded the Confederate District of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona, with his headquarters in Houston. Stringfellow, as a staff ordnance officer, must have been in and out of Walker’s headquarters regularly; I’m sure his path and Joseph Ralston’s must have crossed many times.

Happy Appomattox Day, y’all.

__________

[1] “Horace Stringfellow Rev,” Family Tree “Dianna Lynn Stringfellow Wild,” Ancestry.com (http://trees.ancestry.com/tree/11636774/person/1884888676), accessed March 21, 2015.

[2] “Parish History Notes 25: The Rev. Horace Stringfellow,” The Fork Church website (http://www.theforkchurch.org/About_Us/History/The_Rev_Horace_Stringfellow/), accessed March 21, 2015; John Herbert Claiborne, Seventy-five Years in old Virginia (Petersburg: Neale Publishing Company, 1904), 76.

[3] “Captain Henry Martin Stringfellow.” The Confederate Veteran, October 1862, 484.

[4] Sheryl D. Vanderstel, “The Episcopalians in Nineteenth Century Indiana.” (http//www.connerprairie.org/historyonline/episcopalians.html), accessed March 21, 2015.

[5] Stringfellow, H. Martyn, Nelson’s Battalion of Confederate Artillery. Compiled Service Record, U.S. National Archives.

[6] The Confederate Veteran, 484.

[7] Stringfellow, H. M. General and Staff Officers, Corps, Division and Brigade Staffs. Compiled Service Record, U.S. National Archives (hereafter “Stringfellow Officer CSR”).

[8] Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. XV (S21), 218.

[9] Stringfellow Officer CSR.

[10] Stringfellow Officer CSR.

[11] Stringfellow Officer CSR.

________

Quite a post, Andy. You’ll have to forgive me for commenting prior to reading it in full (which I need to do later, and after which I may add further), but I wanted to interject that Horace Stringfellow was actually rector of my church, from 1835-1840. I’m in the process of writing bio sketches for all of our rectors, so when I came across the post, I was quite interested. Regarding the opinion of slavery, I think there may have been a fine line in the general belief that slavery was justified. We look back upon it one way, while in the context of the time, I think it should be more carefully reconsidered (surprise, surprise, considering how I look on Southern Unionism in the same way). Focusing on the Episcopal apology regarding slavery (made in the 1990s), I think they may have “thrown out the baby with the bath water”. There are some within the Episcopal Church, in Virginia, who, by their actions, suggest a thinking that might best be considered within the context of the time as more forward thinking. Bishop Meade, for example… though he did not consider slavery a sin… and was highly supportive of publishing works to encourage the Bible as a tool of education with slaves… shows actions through his association with the American Colonization Society, that indicates a moral belief that something needed to be changed. If you read the ACS tracts from this area of Virginia, well… they’re quite fascinating. I plan on featuring them in an upcoming post.

Thanks for this. You will undoubtedly uncover more about Horace Stringfellow than I did, and I look forward to learning more.

By the way, hat tip on bringing Thornton on my radar. On another note, where did you come across the image of Horace?

I

swiped it fromfound it on Ancestry. I looks like it’s from an art or museum catalog, but I have no idea which.Excellent post, Andy. An interesting read about a man who lived through a time of great change. Nicely done.

Thanks.

What did this guy do for Davis Rice Atchison? Is it the same Stringfellow how helped Atchison kill and terrorize in Kansas to spread slavery? Do you know about David Rice Atchison speech, bragging about killing to spread slavery?

Read the post and you can answer your own question.

Hi. I just found this excellent post while doing some research on Horace Stringfellow. It helped me fill in some dates left out of Lizzie Stringfellow Watkins rather vague memoir about her father Horace, and family, which was published in 1930. My primary interest in Horace is actually his father’s ( Robert II Stringfellow) “Retreat Farm” on the Rapidan River at Raccoon Ford. Horace’s daughter Lizzie S. Watkins has some great anecdotes about life at Retreat farm, pre-war. (Rev. Thornton Stringfellow’s estate “Bel Air” was 4 miles down the river, near Tobacco Stick Ford). Both estates are no longer standing, although a new house was built over the foundation of Thornton’s home. Thornton and family also owned the Summerduck estate, still standing, near Morton’s Ford. All the Stringfellow’s had large families, and according to Lizzie “13 brothers & cousins” had enlisted in the Confederate Service. It gets confusing because several shared the same or similar names. Thanks for the excellent post ! Brad Forbush (www.13thmass.org)

Brad, I’m glad you found this material useful. The Stringfellows were everywhere, and it’s only unfortunate that they were not more imaginative in naming. Would’ve saved folks these days a lot of confusion.

They really were everywhere. A fictionalized version of one of them even ended up on the PBS series “Mercy Street.“

This waas great to read