“It seemed the choked voice of a race at last unloosed”

Emancipation Day ceremonies with the 1st South Carolina Infantry, Camp Saxton, Port Royal, South Carolina, January 1, 1863. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly.

Emancipation Day ceremonies with the 1st South Carolina Infantry, Camp Saxton, Port Royal, South Carolina, January 1, 1863. Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly.

Contrary to claims often made, when it formally took effect on January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation immediately freed thousands of enslaved persons across areas of the South then occupied by Federal forces. As Eric Foner outlined in his Pulitzer Prize-winning history, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery, one of the most important of these was in the Sea Islands along the South Carolina and Georgia coasts, territories that were still nominally in rebellion but had taken by Federal forces early in the war, to use as a staging position for further campaigns up and down the coast. And in the Sea Islands, there was probably no bigger celebration than at Port Royal, South Carolina, where a formal ceremony was held by, and for, the first black regiment in the Union Army, the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry (later re-designated the 33rd USCT). The event was so dramatic that it forms the opening scene of Stephen Ash’s history of the 1st and 2nd South Carolina, Firebrand of Liberty.

Today, on the sesquicentennial of that event, we have three first-hand accounts of that celebration — one from an African American woman, an escaped slave, employed by the regiment as a laundress; a white abolitionist woman from New England, who had come to the Sea Islands to do volunteer work with the Freedmen and -women there; and the white officer commanding the 1st South Carolina.

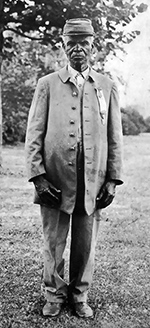

Pension Records for Louis Napoleon Nelson

One of the best-known “black Confederate soldiers” is Louis Napoleon Nelson (right, c. 1846 – 1934), due in large part to the advocacy of his grandson, Nelson Winbush. There are any number of claims made for the nature of Nelson’s service, such as these:

One of the best-known “black Confederate soldiers” is Louis Napoleon Nelson (right, c. 1846 – 1934), due in large part to the advocacy of his grandson, Nelson Winbush. There are any number of claims made for the nature of Nelson’s service, such as these:

[Winbush’s] grandfather, Louis Napolean Nelson, was a private in Co. M, 7th Tennessee Cavalry of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. Private Nelson was a slave at the start of the war. He began his military service as a cook, then a rifleman, and finally a chaplain.

Virtually nothing, however, has been offered in the way of documentation of such claims. So in the interest of injecting something tangible into future discussions of Nelson’s activities during the war, here is his 1921 Tennessee Confederate pension file (PDF).

___________

Spielberg Lays Bare the Ugly Politics of Emancipation

Smithsonian.com has a long feature by Roy Blount, Jr. on the making of Spielberg’s Lincoln, in particular the way it challenges common tropes about the 16th president. The film focuses on Lincoln’s efforts to pass the 13th Amendment in early 1865. Blount’s entire piece is worth reading, but I’m especially impressed that Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner seemingly pull no punches when it comes to the pervasive, casual bigotry of 19th century Americans and the hard-nosed, carefully-crafted political maneuvering necessary to pass such a measure in 1865:

[The film] provides no golden interracial glow. The n-word crops up often enough to help establish the crudeness, acceptedness and breadth of anti-black sentiment in those days. A couple of incidental pop-ups aside, there are three African-American characters, all of them based reliably on history. One is a White House servant and another one, in a nice twist involving Stevens, comes in almost at the end. The third is Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln’s dressmaker and confidante. Before the amendment comes to a vote, after much lobbying and palm-greasing, there’s an astringent little scene in which she asks Lincoln whether he will accept her people as equals. He doesn’t know her, or her people, he replies. But since they are presumably “bare, forked animals” like everyone else, he says, he will get used to them. Lincoln was certainly acquainted with Keckley (and presumably with King Lear, whence “bare, forked animals” comes), but in the context of the times, he may have thought of black people as unknowable. At any rate the climate of opinion in 1865, even among progressive people in the North, was not such as to make racial equality an easy sell. In fact, if the public got the notion the 13th Amendment was a step toward establishing black people as social equals, or even toward giving them the vote, the measure would have been doomed. That’s where Lincoln’s scene with Thaddeus Stevens [Tommy Lee Jones, above] comes in. _____ Stevens is the only white character in the movie who expressly holds it self-evident that every man is created equal. In debate, he vituperates with relish—You fatuous nincompoop, you unnatural noise!—at foes of the amendment. But one of those, Rep. Fernando Wood of New York, thinks he has outslicked Stevens. He has pressed him to state whether he believes the amendment’s true purpose is to establish black people as just as good as whites in all respects. You can see Stevens itching to say, “Why yes, of course,” and then to snicker at the anti-amendment forces’ unrighteous outrage. But that would be playing into their hands; borderline yea-votes would be scared off. Instead he says, well, the purpose of the amendment— And looks up into the gallery, where Mrs. Lincoln sits with Mrs. Keckley. The first lady has become a fan of the amendment, but not of literal equality, nor certainly of Stevens, whom she sees as a demented radical. The purpose of the amendment, he says again, is — equality before the law. And nowhere else. Mary is delighted; Keckley stiffens and goes outside. (She may be Mary’s confidante, but that doesn’t mean Mary is hers.) Stevens looks up and sees Mary alone. Mary smiles down at him. He smiles back, thinly. No “joyous, universal evergreen” in that exchange, but it will have to do. Stevens has evidently taken Lincoln’s point about avoiding swamps. His radical allies are appalled. One asks whether he’s lost his soul; Stevens replies, mildly, that he just wants the amendment to pass. And to the accusation that there’s nothing he won’t say toward that end, he says: Seems not.

![]()

If Blount’s recounting of the film is accurate, then this movie may end up doing a tremendous service to the public’s understanding of that pivotal moment in American history. It may well do for the public’s understanding of Lincoln what Glory did, a generation ago, for recognition of the role African American soldiers played in that conflict. The popular image of Lincoln pure and unblemished saint-on-earth has always been a false and ultimately damaging one, as much as the “Marble Man” has been for Lee. Lincoln’s contemporaries didn’t see him that way. For all that Lincoln was branded as a radical abolitionist in the South, real abolitionists knew he was not one of them. According to Blount, Stevens called Lincoln “the capitulating compromiser, the dawdler,” and even Frederick Douglass, who overcame a deep mistrust of Lincoln and the Republicans in the winter of 1860-61 to become one of the president’s strongest allies and supporters, understood that Lincoln was a man who retained his own biases, yet constantly challenged himself to move beyond those. Lincoln was also a man who, regardless of his personal beliefs, had to work (like all presidents before and since) within the constraints of the political realities of the day. It was Lincoln’s willingness to work the political angle — to cajole, to flatter, to intimidate, to compromise when he had to — that allowed him to accomplish things that a firebrand like Stevens never could have, no matter how righteous his cause. As Blount says, “Stevens was a man of unmitigated principle. Lincoln got some great things done.”

There’s a saying that’s been thrown around quite a bit in the last few years, “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” In other words, don’t pass up an opportunity to get most of what you want, for the sake of not being able to get everything you want. That’s good advice now, and it was undoubtedly a notion Lincoln — smart lawyer and brilliant politician that he was — would have agreed with.

When the movie hits theaters in a couple of weeks, I’m sure it will be lazily denounced in some quarters as just so much Lincoln mythologizing. A few more industrious folks will likely cite scraps of dialogue from the film to “prove” that ZOMG those Yankees were racists!. They already seem to be priming themselves to denounce it as a failure if it fails to smash every box-office record, ever. In truth, though, I think they may have a lot more to worry about with this film than the prospect of it being a big-screen affirmation of the caricatured, saintly Lincoln. If the movie is anything like Blount claims it is, it will depict Lincoln and those around him as gifted, resolute but often flawed and complex mortals who struggled and bickered and fought, and eventually accomplished great things — things like the 13th Amendment that seem so obviously right now, but were anything but assured then. If the audience takes away that understanding of the events surrounding the close of the war, it will do far more good than any exercise in hagiography might.

I can’t hardly wait.

___________

UPDATE, October 29: Over at Civil War Talk, a member asks why Frederick Douglass is not depicted in the film.

It’s a great question, and I don’t know the answer. But there’s no point in having a blog if one can’t speculate a little, so here goes:

It may be in part because Douglass was not physically present during the events depicted in the main part of the film, which focuses on passage of the 13th Amendment and the Hampton Roads Conference, which took place in January and early February 1865. I believe Douglass resided in Rochester, New York during the entire period of the war, and as nearly as I can tell, Douglass and Lincoln only met face-to-face on three occasions: in August 1863, when Douglass met with the president to urge him to equalize the pay between white and black Union soldiers; at the White House a year later, when Lincoln summoned Douglass to reaffirm his (Lincoln’s) commitment to ending slavery and to ask Douglass to use his connections to get as many enslaved persons within Union lines in the event he lost the election that fall and a new administration would end the war before decisively defeating the Confederacy; and in early March 1865, when Douglass was ushered into the president’s presence briefly at an inaugural reception to congratulate him on his reelection. This last event, though close to the time frame of the Spielberg film, was not really a substantive meeting that would have particular bearing on the story of the film.

So if my understanding of the structure of the movie is correct, there’s an easy (if not especially satisfying) explanation for his absence from the screen. What will be most interesting to see is whether Douglass’ presence is nonetheless felt in the film — if his words, his writings, his agitating — show up in the script, in allusions by other characters, in the dialogue, or elsewhere. (Elizabeth Keckley’s character [right] would be the obvious opportunity to do this, film-wise, as she admired Douglass and wrote of his being brought to meet the president in March 1865.) The real Frederick Douglass didn’t attend cabinet meetings or negotiations with representatives of the Confederate government aboard River Queen, but he nonetheless exerted a profound influence behind the scenes in both the decision to enlist black troops for the Union and in the struggle to make emancipation permanent in the closing months of the war. If Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner can pull that off — making Douglass and his influence a character in the film without his actually being in the film — that will be remarkable.

So if my understanding of the structure of the movie is correct, there’s an easy (if not especially satisfying) explanation for his absence from the screen. What will be most interesting to see is whether Douglass’ presence is nonetheless felt in the film — if his words, his writings, his agitating — show up in the script, in allusions by other characters, in the dialogue, or elsewhere. (Elizabeth Keckley’s character [right] would be the obvious opportunity to do this, film-wise, as she admired Douglass and wrote of his being brought to meet the president in March 1865.) The real Frederick Douglass didn’t attend cabinet meetings or negotiations with representatives of the Confederate government aboard River Queen, but he nonetheless exerted a profound influence behind the scenes in both the decision to enlist black troops for the Union and in the struggle to make emancipation permanent in the closing months of the war. If Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner can pull that off — making Douglass and his influence a character in the film without his actually being in the film — that will be remarkable.

I can’t hardly wait.

___________

Anticipating Lincoln

On Sunday evening 60 Minutes did a story on Steven Spielberg and his upcoming film, Lincoln. Much of the interview focused on the way Spielberg’s childhood and relationship with his parents, particularly his father, has been reflected in his films. That’s pretty interesting in its own right, but I do wish more time had been spent on Lincoln.

As a filmmaker, Spielberg has never been known for complex characterizations or ambiguous moral messages. (Or realism.) This film is decidedly different in tone, something the director himself acknowledges. It’s not aimed at the summer blockbuster crowd:

Lesley Stahl: There’s not a lot of action. There’s no Spielberg special effects. Steven Spielberg: Right. Lesley Stahl: It’s a movie about process and politics. Have you ever done a movie even remotely– Steven Spielberg: Never. Like this? Lesley Stahl: Not even close. Steven Spielberg: Never. No. I knew I could do the action in my sleep at this point in my career. In my life, the action doesn’t hold any– it doesn’t attract me anymore. Narrator: With only one brief battle scene, the movie’s more like a stage play with lots of dialog as Lincoln cajoles and horse trades for votes.

![]()

Spielberg and his team made a pretty fascinating decision, to focus the film on the last months of Lincoln’s life and his efforts to pass the 13th Amendment, that abolished slavery throughout the United States. The Union military victory was clearly in sight at that point, and Lincoln was trying to make permanent the de facto emancipation brought about by the Emancipation Proclamation and the advance of Federal armies across the South. As we’ve noted before, Lincoln’s commitment to ending chattel bondage permanently by embedding it in the Constitution is evidenced by the fact that he signed the original text of the amendment as passed by both houses of Congress, even though the president has no formal role in approving or endorsing constitutional amendments. The Emancipation Proclamation gets lots of attention, but is also too often misrepresented as the be-all and end-all of emancipation, when it was (as any serious historian will tell you) a temporary, limited, wartime measure, a single, important milestone on the path to real, permanent emancipation. (A path, by the way, that begins with Spoons Butler’s 1861 “contraband” policy at Fort Monroe.) The Emancipation Proclamation is not Lincoln’s legacy; the 13th Amendment rightly is.

Then there’s this, which is an interesting approach, although not one I’m sure I agree with:

![]()

Narrator: Although Spielberg took great pains to be historically accurate, he made what some will see as a curious exception in this scene. Steven Spielberg: Some of the Democrats that were voting against the [13th] Amendment, we changed their actual names. So if you go through the names that we call out on the vote, you’re not going to find a lot of those names that conform to history. And that was in deference to the families.

![]()

All of this effort and nuance will likely be wasted on the True Southron™ crowd, who are already carping about the film’s likely omission of black Confederates and predicting its dismal failure at the box office. I suspect most of them will refuse to watch the movie, though that will hardly stop them from complaining about its content, real or imagined. While history buffs will be arguing about details — whether this character actually said that, or whether such-and-such scene really happened or is a composite of several actual events — the Southrons will be more vaguely angered that the film exists at all, and that it depicts Lincoln as genuinely committed to ending slavery, willing to push the boundaries of his office and the political landscape to as much as he dared to accomplish that goal. That notion is an anathema to the Southrons, because it puts Lincoln, whatever else his faults, squarely on the right side of the great moral issue facing Americans in the 19th century. Instead they will rehash Lincoln’s casual bigotry against African Americans (true, although almost universal among white Americans in that day), and his willingness to consider voluntary recolonization of freedmen to Africa — an idea that long predated Lincoln’s public life and long survived him, as well. These are, after all, the people who can say with a straight face that Lincoln was “a bigger racist than I ever knew,” and more deserving of moral condemnation than their own ancestors who actually owned slaves. As I wrote several months back,

![]()

Confederate apologists often point to these ugly examples and say, “Lincoln believed so-and-so, ” or “Lincoln said such-and-such.” They do this reflexively, as a means of deflecting criticism of slavery in the the South. Such mentions of Lincoln are often narrowly true, but they miss the larger, and much more important, truth. . , which is that Lincoln himself changed and grew over time. The president who told “darkey” jokes also had Frederick Douglass as a visitor to the White House in 1863, the first African American to enter that building not as a servant or laborer, but as a guest. The president who’d said he would be willing not to free a single slave if it would preserve the Union also asked Douglass, in the summer of 1864, to use his contacts to get as many slaves into Union lines as he could before that fall’s presidential election, which Lincoln fully expected to lose. The chief executive who had toyed with the idea of re-colonizing former slaves back to Africa publicly suggested, just days before his death, that suffrage should be extended to at least some freedmen, specifically those who’d served in the Union army.

![]()

Lincoln Derangement Syndrome is very real, and Spielberg’s film is certain to push some folks over the edge. So don’t expect much effort from the Confederate Heritage™ crowd to take the movie on its own terms, or to acknowledge anything positive about the 16th president — just a lot of vague complaining about “PC Hollywood” or the “Lincoln myth,” and so on, without much reference to the specific content of the film itself.

For the rest of us, though, it’s looking like this is going to be a film that delves into a part of Lincoln’s life that’s never been brought to the big screen before. I sure it will give historians and bloggers much both to praise and criticize in the coming weeks. My hope is that, like Glory, Lincoln will be a film that, while containing inevitable small historical inaccuracies, will nonetheless tell a greater true story, will loom large in the general public’s understanding of the conflict and inspire a renewed interest in it.

I can’t hardly wait.

_____________

Parthena and George, Atheline and Dan

I talk about slavery and slaveholding a lot on this blog, for reasons that I hope should be obvious — because it was the issue central to secession and the war, because it formed the basis of capital and wealth in the slaveholding states, and because the standard Confederate “heritage” narrative routinely either diligently ignores the issue altogether, or depicts it as a benign or even positive condition for those held in bondage. And of course, the war culminated in the emancipation of roughly four million persons and made them citizens. I understand that it makes people uncomfortable; it does me, too, because it’s a hard subject. But it should be uncomfortable, and I don’t think one can talk seriously about the conflict without these issues coming up — a lot.

So today, on the official release date of The Galveston-Houston Packet: Steamboats on Buffalo Bayou, it seems like a good time to address the issue of slavery and slaveholding as it pertains to a man named John H. Sterrett (c. 1815-1879), who’s a central character in the book. Sterrett was a steamboat pilot and master who came to Texas from the Ohio River in the winter of 1838-39, and in the ensuing four decades became by far the best-known personage on the route between Galveston and Houston. In 1858 it was estimated that he’d made the 70-mile run between the two cities about 4,000 times — an accomplishment that is entirely plausible.[1] During the Civil War he served as Superintendent of Transports for the Texas Marine Department, a quasi-military organization that provided logistical and naval support for the Confederate army in Texas. After the war he played an active role in re-establishing the steamboat trade between the cities, and inaugurated the use of steam tugs by the Houston Direct Navigation Company, a transition that would allow the company to survive well into the 20th century. Sterrett retired from the boats in 1875, two years before the company abandoned passenger service on the route, and the same year dredging began on what would eventually become the Houston Ship Channel.[2] Sterrett’s story is, in a very real sense, the story of the steamboat trade on Buffalo Bayou.

Since submitting the final edits I realized that, although I mention slavery several times in the book — slave labor was a routinely used on steamboats in Texas and the deep South, and it comes up again and again in contemporary documents — I never really addressed it in connection with Sterrett. This post corrects that.

John Sterrett was a slaveholder. Period, full stop.

I have been unable to find documentation of Sterrett’s slaveholding up through the slave schedules of the 1850 U.S. Census, but it’s likely he was one prior to that time. The earliest documentation I’ve found to date is from the fall of 1851, when Sterrett sailed from Galveston to New Orleans aboard the steamer Mexico, Captain Henry Place. Upon arrival at New Orleans, Sterrett completed a required “Manifest of Slaves,” which described the enslaved persons he was traveling with, and attesting to their legal transport coastwise between states. In this case, the enslaved person was a nine-year-old child, a girl named Parthena, who was recorded as being four-feet-three, and “yellow” in complexion. It is not clear whether Parthena was accompanying Sterrett as a servant, or ended up in one of New Orleans’ large slave markets.[3]

The next piece of evidence is another manifest, again from Galveston to New Orleans, dated March 1856 aboard the steamship Louisiana, Captain John F. Lawless. In this case, the chattel were two men, George and Frank, their ages given as 32 and 34 respectively. Sterrett was not listed on the manifest as their owner, but as their shipper. Sterrett may have been traveling to New Orleans on other business — he frequently took personal charge of new steamboats brought out to Texas for the Buffalo Bayou route — and agreed to oversee the transportation of these two men either to their owner in New Orleans or to the slave market there. [4]

The third manifest dates from late November 1858, and covers Sterrett’s voyage from New Orleans to Galveston with the new steamboat Diana. This boat, a 239-ton sidewheel steamboat built at Brownsville, Pennsylvania, would become one of the premier boats on the Buffalo Bayou route in the brief period remaining before the war. (A much larger postwar boat of the same name would become better known still.) This time, Sterrett brought with him two enslaved men — Mickly and Dan, ages 32 and 28, and a woman Atheline, aged about 40. These three were all listed as property of Captain Sterrett.[5]

The third manifest dates from late November 1858, and covers Sterrett’s voyage from New Orleans to Galveston with the new steamboat Diana. This boat, a 239-ton sidewheel steamboat built at Brownsville, Pennsylvania, would become one of the premier boats on the Buffalo Bayou route in the brief period remaining before the war. (A much larger postwar boat of the same name would become better known still.) This time, Sterrett brought with him two enslaved men — Mickly and Dan, ages 32 and 28, and a woman Atheline, aged about 40. These three were all listed as property of Captain Sterrett.[5]

The final snapshot we have of Sterrett’s slaveholding comes from the slave schedule of the 1860 U.S. Census. At that time, Sterrett and his wife, Susan, had six children, ranging in age from 1 to 14. The lived on the corner of San Jacinto and McKinney Streets, in what is now the heart of downtown Houston.[6] A contemporary newspaper account described his new residence as “quite an addition to the appearance of that neighborhood.”[7] At that time, on the eve of the war, Sterrett owned six slaves. As usual, no names are listed in the slave schedule, only sex, age and complexion. There was a ten-year-old girl in the group, but the rest — two women and three men — were between the ages of 20 and 40. It seems likely that two of the enslaved persons listed — a woman, age 40 and listed as “mulatto,” and a man, age 34, correspond to Mickly and Atheline, who had been carried to Texas two years before on Sterrett’s new boat, Diana.

That’s all the documentary record says (so far) about Sterrett’s slaveholding, but we can make some informed guesses about them and their roles. Sterrett does not seem to have invested heavily in land, or to have engaged in large-scale agriculture. The enslaved persons belonging to Sterrett were probably mostly household servants, although it’s almost certain that some of them, the men particularly, were put to work aboard Sterrett’s Buffalo Bayou steamboats at one time or another. Use of slave labor aboard riverboats in Texas appears to have been very common in the antebellum years, and the casualty lists of almost every steamboat disaster of the period includes at least one enslaved person. When the steamboat Farmer blew up in the early morning hours of March 22, 1853, killing at least 36 people, newspaper accounts indicated the boat had a crew of 27. Eight of these were identified by name and position (pilot, clerk, engineer, etc.). Of the remaining nineteen — almost all of whom must have been firemen, deckhands or cabin stewards — at least eleven were enslaved persons belonging to third parties apparently not connected to the boat’s officers or owners. Several years after the disaster, the prevailing rate for slaves to work as deckhands on the Houston-Galveston run was $480 per year—paid to their owner, of course. (Two other Farmer crewmen are listed as “German” and were probably recent immigrants from Europe.)[8] When Bayou City blew up her boilers on Buffalo Bayou on September 28, 1860, among the ten or more dead were two African American men among the crew who were property of that boat’s master, James Forrest.[9]

Although Sterrett clearly bought and sold a number of slaves, there’s nothing in the record suggesting that was a business venture of his. He was not a slave trader, nor did he speculate in the trade, as some prominent men in the South did. Sterrett seems to have been fairly typical for a man of his means in that time and place.

I’ve written before about one of my own ancestors who was a slaveholder – on about the same scale as Sterrett, it turns out – which is a fact I had suspected, but was left to find out on my own, fairly recently. That troubles me, because that’s so fundamentally antithetical to my own views and beliefs. It’s something that I just don’t like to think an ancestor of mine embraced.

Sterrett’s case feels the same. I’ve “known” Sterrett for almost 20 years, as well or better than many of my own relatives from that period, because (unlike them) the old steamboat captain left a long paper trail. He was praised frequently in the newspapers for four decades – a pretty sure sign he was well-liked by the traveling public. One paper in 1851 referred to him as “that prince of Steamboat Captains.” Another noted that he had a running gag he played habitually with the clerk of whatever boat he was on, theatrically ordering the man below decks to check the cargo again, so Sterrett could entertain the female cabin passengers himself. When he died, one obituary noted, he was relatively poor because, despite his gruff exterior, he was generous to a fault when it came to providing assistance to others. “No man,” another said, “had a kinder or warmer heart.”[10]

Pretty decent guy, seems like. But also a slaveholder. This stuff is hard.

Nearly fifty years ago Barbara Tuchman gave a talk at a professional conference called “The Historian’s Opportunity,” in which she argued that being perfectly objective and unbiased was neither desirable – “his work would be unreadable – like eating sawdust” – nor even really possible. “There are some people in history one simply dislikes.”[11] My situation with Sterrett is just the opposite; I’ve come to like him over the years, and it’s troubling to have to shade that image with a detailed and specific knowledge of his close and long-standing involvement with chattel bondage.

No heroes, only history.

[1] Galveston Civilian and Gazette, May 4, 1858, 1.

[2] Galveston Daily News, November 26, 1875, 4.

[3] John H. Sterrett, Slave Manifests of Coastwise Vessels Filed at New Orleans, Mexico, 1807-1860. Steamer Mexico, Galveston, Texas to New Orleans, Louisiana, November 4, 1851. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Microfilm Serial: M1895.

[4] John H. Sterrett, Slave Manifests of Coastwise Vessels Filed at New Orleans, Louisiana, 1807-1860. Steamer Mexico, Galveston, Texas to New Orleans, Louisiana, March 13, 1856. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Microfilm Serial: M1895.

[5] John H. Sterrett, Slave Manifests of Coastwise Vessels Filed at New Orleans, Louisiana, 1807-1860. Steamer Diana, New Orleans, Louisiana to Galveston, Texas, November 25, 1858. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Microfilm Serial: M1895.

[6] U.S. Census of 1860; Ward 4, Houston, Harris County, Texas, 151.

[7] Houston Republic, January 30, 1858

[8] Clipping from an unknown periodical, April, 23, 1853, Galveston and Texas History Center, Rosenberg Library, Galveston; Louis C. Hunter, Steamboats on the Western Rivers (New York: Dover, 1993), 448–50; Kenneth M. Stampp, The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the AnteBellum South (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972), 414–15. One of the slaves killed in the Farmer accident belonged to Capt. Delesdernier, himself an old Buffalo Bayou pilot.

[9] C. Bradford Mitchell, ed., Merchant Steam Vessels of the United States, 1790–1868 (The Lytle-Holdcamper List) (Staten Island, New York: Steamship Historical Society of America, 1975), 18; Frederick Way, Jr., Way’s Packet Directory, 1848–1983 (Athens: Ohio UniversityPress, 1984), 40; Galveston Civilian and Gazette Weekly, September 25, 1860, 3; Colorado Citizen, September 29, 1860, 2; Galveston Civilian and Gazette Weekly, October 2, 1860, 3.

[10] Austin South-Western American, July 30, 1851, 2; Galveston Daily News, June 19, 1927; Galveston Daily News, June 19, 1879; clipping from an unidentified Houston newspaper, June 19, 1879, author’s collection.

[11] Barbara W. Tuchman, “The Historian’s Opportunity.” In Practicing History: Selected Essays by Barbara W. Tuchman (New York: Ballantine, 1982), 59-60.

___________

Images: Top, firemen on a Mississippi steamboat, Every Saturday Magazine, 1871. Right, advertising broadside for Sterrett’s steamer Diana, c. 1859.

They Can’t Help Themselves, Can They?

Has anyone else noticed that the official blog of the Flagging movement, Southern Flaggers in Action, has at least temporarily abandoned its stated mission of “forwarding the colors” or honoring Confederate veterans or whatever, and is now a platform for straight-up race trolling the presidential election, ominously asking, “Are Whites Being Threatened If Obama Loses The Election?“:

![]()

There are several others mentioned in the article, most of the same literary caliber, all threatening general mayhem should Romney win the election. If some of these gentle folk make good their boasts it would give Comrade Obama a wonderful pretext to declare martial law and start the government crackdown on all those terrorist home schoolers, ex-veterans and Christians–you know–all those potential terrorists who cling to their Bibles and guns. He’d like nothing better and his core support just might be in the process of being programmed to do what he wants. They are what the Communists refer to as “useful idiots.” Who in his right mind can’t see the threat here? Do what we want and re-elect Obama–or else! These people have been progrrammed [sic.] into thinking that if Obama loses they will have to give up their “free” Obama cell phones, all the other freebies they’ve been promised, their food stamps and all the rest, all of which they obtain at the expense of us folks who are still willing to work for a living. No wonder the economy is terrible, when those of us who still work are forced to foot the bill for those who won’t. . . . In the event that such an occurrence does take place and Obama’s supporters decide to take to the streets to vent their racism (because that’s all it really is for most of them) then I think that those among the populace that share a determination to defend themselves and their property by exercising their Second Amendment rights will be pretty much left alone while the rioters go after easier victims. The only variable in that equation is–should he lose–will Obama then declare martial law and come for everyone’s guns so the rioters won’t have any opposition??

![]()

Nat Turner and Denmark Vesey may be dead and buried, but they still ride in the fever dreams of some people.

______________

Did Jefferson Davis’ Son Serve in the U.S. Navy?

Slave quarters on Jefferson Davis’ plantation, Library of Congress.

Did Jeff Davis’ son by an enslaved woman serve in the U.S. Navy on the Mississippi?

Over at Civil War Talk we had a discussion over this item that appeared, almost word-for-word, in numerous Northern newspapers beginning in February 1864:

The London Star of January 15th says a letter from a gentleman occupying a high position in the United States, contains the following story: This reminds me says the writer, that Jeff. Davis’ son, by his slave girl Catherine, was in the Federal service on board of one of our gunboats, in the Mississippi, for several months—a likely mulatto. Among the letters of Jeff, taken at his house by our Illinois troops, there was a batch of quarrelsome epistles between Jeff. and Mrs Davis, touching his flame Catherine. Mrs. Davis upbraided her husband bitterly. I have this story from one of the highest officers in the squadron, who had the negro Jeff. on board his gunboat, and who himself read the letters and suppressed them.

It sounds exactly like the sort of scurrilous accusation that Northern readers would want to hear about Jeff Davis, like the story the following year about his being captured by Federal troops while wearing a dress. It has the ring of tabloid-y trash, and it’s easy to dismiss on that account.

However, there’s another, longer story from the Bedford, Indiana Independent of July 13, 1864 (p. 2, cols. 3 and 4) that, while differing in several details, largely supports the claim in the London Star, and provides substantial corroborative detail:

Jeff. Davis and His Mulatto Children — Abolitionists are constantly accused in copperhead papers of trying to bring about an amalgamation of whites and blacks; but those papers are very careful to conceal from their readers, as far as possible, such facts as those related in the following extract of a letter from an officer in the Army to a Senator in Washington: “While at Vicksburg, I resided opposite a house belonging to a negro [sic.] man who once belonged to Joe Davis, a brother of Jeff. Learning this, I happened one day to think that he perhaps would know something about the true story told in the London Times, that there was a son of Jeff. Davis, the mother of whom was a slave woman, in our navy. The next time I met the man I asked him if he had ever known Maria, who had belonged to Jeff. Davis, and was the mother of some of his children? He replied that he had not known Maria, but that he knew his Massa Joe Davis’ Eliza, who was the mother of some of Massa Jeff’s children. I then inquired if she had a son in the navy? He replied that she had — he knew him — they called him Purser Davis. He said that Eliza was down the river some thirty miles, at work on a plantation. The next day, as I was walking down the street, I met the man, who was driving his mule team, and he stopped to tell me that Eliza had returned. A few moments afterwards he came back, and pointing to one of two women who came walking along, he said she was the one of whom we had been talking. When she came up, I stopped her, and inquired whether she had not a son who would like to go North. She replied yes and added that she would like to go too. I told her that I only wanted a lad. She said that her son had gone up the Red River on board the gunboat Carondelet, but when he returned she would be pleased to have him go. ‘Well,’ said I, ‘some say that Jeff. Davis is your son’s father — do you suppose it’s so?’ ‘Suppose,’ she cried with offended pride, ‘I’s no right to suppose what I knows — am certain so. Massa Jeff. was the father of five of my children, but they are all dead but that boy, and then I had two that he wasn’t the father of. There’s no suppose about it.’ Perhaps if the boy gets back safe on the Carondelet, you may see him in Boston some of these days.”

Here’s where it gets interesting. The correspondent recorded the young Carondelet sailor’s name he was told as “Purser Davis.” There was, in fact, not a Purser Davis, but a Percy Davis in the crew of U.S.S. Carondelet at that very moment. According the NPS Soldiers and Sailors System, a fourteen-year-old named Percy Davis was enrolled for a term of one year as a First Class Boy on the ship at Palmyra, Mississippi on November 16, 1863 — almost exactly two months before the original news item appeared in London. He remained on board Carondelet at least through the muster dated January 1, 1865. Davis is described as being mulatto in complexion, and five-foot-one. Percy Davis gave his birthplace as Warren County, Mississippi — the county of Vicksburg, and where both Jefferson Davis and Joseph E. Davis were major slaveholders, with 113 and 365 slaves respectively at the time of the 1860 U.S. Census.

Does this prove the original story is true? No, but it does add considerable additional detail, some of which is corroborated. The first news item is vague, without any specifics, but the second is detailed and at least partly verifiable. There’s enough here that the claim of Davis’ natural son having served aboard a Union gunboat cannot, in my view, be dismissed out-of-hand as Civil War tabloid trash. The possibility of its truth merits further digging.

_____________

“. . . how many may be of use without putting guns in their hands.”

While doing some research on another topic recently I came across a reference to this item from the Richmond, Virginia Examiner of January 13, 1864. In the third winter of the war, things were looking dim for the Confederacy — though not nearly as dim as they would eventually be — and there were already suggestions that African Americans be enlisted as soldiers in the Confederate army. In this piece, an anonymous “officer of distinction” in Confederate service rejects that idea, and instead argues that more extensive use of black laborers would “restore to duty in the field forty thousand white men.”

While doing some research on another topic recently I came across a reference to this item from the Richmond, Virginia Examiner of January 13, 1864. In the third winter of the war, things were looking dim for the Confederacy — though not nearly as dim as they would eventually be — and there were already suggestions that African Americans be enlisted as soldiers in the Confederate army. In this piece, an anonymous “officer of distinction” in Confederate service rejects that idea, and instead argues that more extensive use of black laborers would “restore to duty in the field forty thousand white men.”

EMPLOYMENT OF NEGROES IN THE ARMY. — An officer of distinction in the Confederate army writes as follows: The subject of placing negroes [sic.] in the army is attracting some attention. The following memoranda shows approximately how many may be of use without putting guns in their hands. Premising that we have in the field one hundred brigades, allow for each as: Engineer laborers……………………….50……….5,000

Butchers……………………………………….5………….500

Blacksmiths………………………………….2………….200

Wheelwrights……………………………….2………….200

Teamsters……………………………………50………5,000

Cooks………………………………………….40………4,000

Hospital nurses and cooks & c………40………4,000

Shoemakers…………………………………20………2,000 Total…………………………………………………….20,700 [sic., 20,900] To which may be added for the various mechanical departments under the control of the Government, as labourers, & c………………………………………….10,000 And as labourers on fixed fortifications…….20,000 Making a total of……………………………………..50,700 [50,900] The employment of this number would restore to duty in the field forty thousand white men.

There are three things that are worth noting about this piece.

First, the writer is explicitly opposed to the idea of African Americans serving under arms. He makes no distinction between enslaved persons and free men of color — neither, in his view, is appropriate for service in the ranks as soldiers. Indeed, the writer’s stated intent is to show how these men may be used “without putting guns in their hands.”

Second, the author makes no mention whatever of personal servants to white soldiers, who even then must have numbered in the thousands. This is relevant, because this group includes a majority of individuals hailed as “black Confederates” today. This suggests that this “officer of distinction” in Confederate army did not view those servants as being part of the national government’s greater military effort, which indeed they are not — personal servants are personal servants, period, full stop.

Third, the citation to this news item was found in some handwritten notes from decades ago, taken from a thesis written decades before that. But the notes, and likely the thesis from which they’re taken, record it as a summary of “Negroes in employed in the Army (by the 100 brigades then in the field).” But that’s wrong; this is not a report of current status, but a prospective look at what might be done in the future. (The note-taker almost certainly did not have access to the original newspaper.) This underscores how easy it is to misconstrue an original source, which original error gets repeated by those who follow. It would be interesting to know if other secondary works report these numbers as an actual accounting, rather than a projection based on a proposed policy.

Above all, the author gives no recognition of the modern assertion that there were large numbers of African American men in the ranks, considered soldiers under arms. I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating: real Confederates didn’t know about black Confederates.

____________

Update: In the comments, Rob Baker makes a very important point — this newspaper item comes just days after Patrick Cleburne’s now-famous proposal that the Confederacy embrace emancipation and enlist large numbers of black troops. While no public acknowledgement was made of Cleburne’s proposal at the time, it seems possible that rumors of it were circulating in Richmond. Could this short piece, penned by an anonymous “officer of distinction,” be part of the Confederate government’s effort to quash the idea?

____________

What They Saw at Fort Pillow

![]()

While doing research on something else, I came across a couple of accounts of the aftermath of the Confederate assault on Fort Pillow, written by naval officers of U.S.S Silver Cloud (above), the Union “tinclad” gunboat that was the first on the scene. I don’t recall encountering these descriptions before, and they really do strike a nerve with their raw descriptions of what these men witnessed, at first hand.

These accounts are particularly important because historians are always looking for “proximity” in historical accounts of major events. The description of an event by someone who was physically present is to be more valued than one by someone who simply heard about it from another person. The narrative committed to paper immediately is, generally, more to be valued than one written months or years after the events described, when memories have started to fade or become shaded by others’ differing recollections. Hopefully, too, the historian can find those things in a description of the event by someone who doesn’t have any particular axe to grind, who’s writing for his own purposes without the intention that his account will be widely and publicly known. These are all factors — somewhat subjective, to be sure — that the historian considers when deciding what historical accounts to rely on when trying to reconstruct historical events, and to understand how one or another document fits within the context of all the rest.

Which brings us back to the eyewitness accounts of Acting Master William Ferguson, commanding officer of U.S.S. Silver Cloud, and Acting Master’s Mate Robert S. Critchell of that same vessel.

Ferguson’s report was written April 14, 1864, the day after he was at the site. It was addressed to Major General Stephen A. Hurlbut, commanding officer of the Union’s XVI Corps of the Army of the Tennessee, then headquartered at Memphis. It appears in the Army OR, vol. 57, and the Navy OR, vol. 26.

U.S. STEAMER SILVER CLOUD,

Off Memphis, Tenn., April 14, 1864. SIR: In compliance with your request that I would forward to you a written statement of what I witnessed and learned concerning the treatment of our troops by the rebels at the capture of Fort Pillow by their forces under General Forrest, I have the honor to submit the following report: Our garrison at Fort Pillow, consisting of some 350 colored troops and 200 of the Thirteenth Tennessee Cavalry, refusing to surrender, the place was carried by assault about 3 p.m. of 12th instant. I arrived off the fort at 6 a.m. on the morning of the 13th instant. Parties of rebel cavalry were picketing on the hills around the fort, and shelling those away I made a landing and took on-board some 20 of our troops (some of them badly wounded), who had concealed themselves along the bank and came out when they saw my vessel. While doing so I was fired upon by rebel sharpshooters posted on the hills, and 1 wounded man limping down to the vessel was shot. About 8 a.m. the enemy sent in a flag of truce with a proposal from General Forrest that he would put me in possession of the fort and the country around until 5 p.m. for the purpose of burying our dead and removing our wounded, whom he had no means of attending to. I agreed to the terms proposed, and hailing the steamer Platte Valley, which vessel I had convoyed up from Memphis, I brought her alongside and had the wounded brought down from the fort and battle-field and placed on board of her. Details of rebel soldiers assisted us in this duty, and some soldiers and citizens on board the Platte Valley volunteered for the same purpose. We found about 70 wounded men in the fort and around it, and buried, I should think, 150 bodies. All the buildings around the fort and the tents and huts in the fort had been burned by the rebels, and among the embers the charred remains of numbers of our soldiers who had suffered a terrible death in the flames could be seen. All the wounded who had strength enough to speak agreed that after the fort was taken an indiscriminate slaughter of our troops was carried on by the enemy with a furious and vindictive savageness which was never equaled by the most merciless of the Indian tribes. Around on every side horrible testimony to the truth of this statement could be seen. Bodies with gaping wounds, some bayoneted through the eyes, some with skulls beaten through, others with hideous wounds as if their bowels had been ripped open with bowie-knives, plainly told that but little quarter was shown to our troops. Strewn from the fort to the river bank, in the ravines and hollows, behind logs and under the brush where they had crept for protection from the assassins who pursued them, we found bodies bayoneted, beaten, and shot to death, showing how cold-blooded and persistent was the slaughter of our unfortunate troops. Of course, when a work is carried by assault there will always be more or less bloodshed, even when all resistance has ceased; but here there were unmistakable evidences of a massacre carried on long after any resistance could have been offered, with a cold-blooded barbarity and perseverance which nothing can palliate. As near as I can learn, there were about 500 men in the fort when it was stormed. I received about 100 men, including the wounded and those I took on board before the flag of truce was sent in. The rebels, I learned, had few prisoners; so that at least 300 of our troops must have been killed in this affair. I have the honor to forward a list(*) of the wounded officers and men received from the enemy under flag of truce. I am, general, your obedient servant, W. FERGUSON,

Acting Master, U.S. Navy, Comdg. U.S. Steamer Silver Cloud.

Ferguson’s report is valuable because it is detailed, proximate in time to the event, and was written specifically for reference within the military chain of command. It seems likely that Ferguson’s description is the first written description of the aftermath of the engagement within the Federal’s command structure. Certainly it was written before news of Fort Pillow became widely known across the country, and the event became a rallying cry for retribution and revenge. Ferguson’s account was, I believe, ultimately included in the evidence published by the subsequent congressional investigation of the incident, but he had no way of anticipating that when he sat down to write out his report just 24 hours after witnessing such horrors.

The second account is that of Acting Master’s Mate Robert S. Critchell (right), a 20-year-old junior officer aboard the gunboat. Critchell’s letter, addressed to U.S. Rep. Henry T. Blow of Missouri, was written a week after Ferguson’s report, after the enormity of events at the fort had begun to take hold. If Ferguson’s report reflected the shock of what he’d seen, Critchell’s gives voice to a growing anger about it. Critchell’s revulsion comes through in this letter, along with his disdain for the explanations of the brutality offered by the Confederate officers he’d met, that they’d simply lost control of their men, which the Union naval officer calls “a flimsy excuse.” Crittchell admits to being “personally interested in the retaliation which our government may deal out to the rebels,” but also stands by the accuracy of his description, offering to swear out an affidavit attesting to it.

The second account is that of Acting Master’s Mate Robert S. Critchell (right), a 20-year-old junior officer aboard the gunboat. Critchell’s letter, addressed to U.S. Rep. Henry T. Blow of Missouri, was written a week after Ferguson’s report, after the enormity of events at the fort had begun to take hold. If Ferguson’s report reflected the shock of what he’d seen, Critchell’s gives voice to a growing anger about it. Critchell’s revulsion comes through in this letter, along with his disdain for the explanations of the brutality offered by the Confederate officers he’d met, that they’d simply lost control of their men, which the Union naval officer calls “a flimsy excuse.” Crittchell admits to being “personally interested in the retaliation which our government may deal out to the rebels,” but also stands by the accuracy of his description, offering to swear out an affidavit attesting to it.

UNITED STATES STEAMER “SILVER CLOUD.” Mississippi River, April 22nd, 1864. SIR :-Since you did me the favor of recommending my appointment last year, I have been on duty aboard this boat. I now write you with reference to the Fort Pillow massacre, because some of our crew are colored and I feel personally interested in the retaliation which our government may deal out to the rebels, when the fact of the merciless butchery is fully established. Our boat arrived at the fort about 7½ A. M. on Wednesday, the 13th, the day after the rebels captured the fort. After shelling them, whenever we could see them, for two hours, a flag of truce from the rebel General Chalmers, was received by us, and Captain Ferguson of this boat, made an arrangement with General Chalmers for the paroling of our wounded and the burial of our dead; the arrangement to last until 5 P. M. We then landed at the fort, and I was sent out with a burial party to bury our dead. I found many of the dead lying close along by the water’s edge, where they had evidently sought safety; they could not offer any resistance from the places where they were, in holes and cavities along the banks; most of them had two wounds. I saw several colored soldiers of the Sixth United States Artillery, with their eyes punched out with bayonets; many of them were shot twice and bayonetted also. All those along the bank of the river were colored. The number of the colored near the river was about seventy. Going up into the fort, I saw there bodies partially consumed by fire. Whether burned before or after death I cannot say, anyway, there were several companies of rebels in the fort while these bodies were burning, and they could have pulled them out of the fire had they chosen to do so. One of the wounded negroes told me that “he hadn’t done a thing,” and when the rebels drove our men out of the fort, they (our men) threw away their guns and cried out that they surrendered, but they kept on shooting them down until they had shot all but a few. This is what they all say. I had some conversation with rebel officers and they claim that our men would not surrender and in some few cases they “could not control their men,” who seemed determined to shoot down every negro soldier, whether he surrendered or not. This is a flimsy excuse, for after our colored troops had been driven from the fort, and they were surrounded by the rebels on all sides, it is apparent that they would do what all say they did,throw down their arms and beg for mercy. I buried very few white men, the whole number buried by my party and the party from the gunboat “New Era” was about one hundred. I can make affidavit to the above if necessary. Hoping that the above may be of some service and that a desire to be of service will be considered sufficient excuse for writing to you, I remain very respectfully your obedient servant, ROBERT S. CRITCHELL, Acting Master’s Mate, U. S. N.

![]()

Critchell’s note about the explanation offered by Confederate officers, who argued that the black soldiers “would not surrender and in some few cases [the Confederate officers] ‘could not control their men,’ who seemed determined to shoot down every negro soldier, whether he surrendered or not,” is worth noting. That was the excuse offered at the time, and it remains so almost 150 years later, for those Fort Pillow apologists who acknowledge that unnecessary bloodshed took place at all. Critchell observed at the time that “this is a flimsy excuse,” and so it remains today.

Critchell’s letter also seems to endorse retaliation-in-kind, “because some of our crew are colored and I feel personally interested in the retaliation which our government may deal out to the rebels, when the fact of the merciless butchery is fully established.” This urge is, unfortunately, entirely understandable, and we’ve seen that within weeks the atrocity at Fort Pillow was being used as a rallying cry to spur Union soldiers on to commit their own acts of wanton violence. Vengrance begets retaliation begets vengeance begets retaliation. It never ends, and it’s always rationalized by pointing to the other side having done it before.

It never ends, but it often does have identifiable beginnings. Bill Ferguson and Bob Critchell saw one of those beginnings first-hand.

_____________

Critchell letter and images from Robert S. Critchell, Recollections of a Fire Insurance Man (Chicago: McClurg & Co., 1909).

7 comments