Spielberg’s Lincoln: Reading the Movie

![]()

I finally got to see Spielberg’s Lincoln, and it very much lives up to the hype — as improbable as that sounds. I plan on going back to see it again once more in the theater; there are undoubtedly a lot of small touches and bits of dialogue that I missed the first time through. I might write a little about my own thoughts on the film, once they’ve simmered a while, but there’s been so much already written about it by smart and perceptive folks that I’d like to point to a few other reviews and comments on the film that I found worthwhile.

Over at Past in the Present, Michael Lynch marvels at Lincoln brought to life in Daniel Day-Lewis’ performance:

![]()

It’s not just that Day-Lewis disappears into the role. It’s that his Lincoln is so complete. We’ve had excellent movie Lincolns before, but I don’t think anyone has captured so many aspects of his personality in one performance. You get the gregarious raconteur as well as the melancholy brooder, the profound thinker as well as the unpolished product of the frontier, the pragmatic political operator as well as the man of principle. He amuses the War Department staff with off-color jokes in one scene, then ruminates on Euclid and the Constitution in another. It’s the closest you’re going to get to the real thing this side of a time machine, a distillation of all the recollections and anecdotes from Herndon, Welles, and the other contemporaries into one remarkable character study.

![]()

This actually sneaked up on me. I was sitting there thinking how awkward and ungainly he looks sitting a horse, and realized — but that’s how Lincoln’s contemporaries actually described him. Then I noticed the flat-footed gait, the gangly posture, all true to the character. Above all, he comes across on the screen as tired, bone-weary, but nonetheless focused and determined. Quite remarkable.

A good bit of attention has been given to the absence of Frederick Douglass in the film, particularly by historian Kate Masur in her review in the New York Times. I’ve mentioned before elsewhere that Douglass and Lincoln did not meet face-to-face during the January/February 1865 timeframe of the film, and that Douglass was never part of Lincoln’s inner circle of advisors at any point. But Hari Jones, Curator of the African American Civil War Museum, goes further, arguing (via Jimmy Price) that working Douglass into the script regardless would serve mainly to please modern sensibilities, while doing considerable violence to the historical record:

![]()

As for Masur’s criticism of the film, she admits that it is not historically based. Her criticism is simply a question of interpretive choice, which actually means the historical fiction she prefers for the sake of inclusiveness “even at the margins,” and Douglass is her recommended Negro “at the margins.” Douglass was an advisor to Lincoln many such scholars argue. Yet, to be fair to Masur, she only said he attended the inaugural ball in March 1865. Though many scholars assert that Douglass was the leader of the African American community during the war, he was not. Douglass was the editor of a journal read by more European Americans than African Americans. The young African Americans who fought in the Civil War were more likely to read the journal edited by Robert Hamilton, the Anglo-African, than they were to read the Douglass’ Monthly. Masur’s interpretive choice would have placed Douglass in the movie because she does not know who else to put in the frame. I would love to know the professor’s opinion on the movie Glory, a grossly historically inaccurate film. My guess is that she probably compliments the director’s interpretive choice because Douglass was included in that film. He attended a fictitious party at the fictitious Shaw mansion in Boston and was engaged in a fictitious inner circle conversation with Robert Gould Shaw about fighting to free the Negroes. Such fiction is justified because it reveals “a world of black political debate, of civic engagement and of monumental effort for the liberation of body and spirit,” suggesting, of course, that we must make up such stories. Masur’s criticism of Spielberg’s Lincoln demonstrates a propensity common among many contemporary scholars who seek to provide a view of history (an interpretive choice) that is in fact tokenism. Simply stated if they do not know the Negro who really did something related to the subject matter, they put the most famous Negro of the time, their super Negro, in the story simply to have a Negro in the inner circle. Among contemporary scholars, Frederick Douglass is the affirmative action Negro of the Civil War. I wonder if he would be fond of that dubiously esteemed position.

![]()

Kevin was glad to see the ugly political debate behind the 13th Amendment, which presents a view of mid-19th century white Northerners that historians know, but the general public often does not:

![]()

What I loved most about the movie was the debate on the House floor. I’ve said before that one of the most difficult things to teach is the pervasiveness of racism throughout the country at this time. This comes through clearly in the movie as politicians argue passionately about the consequences of emancipation for white Americans. Blacks will compete for jobs, marry white women, and perhaps one day even vote. While the movie effectively captures the importance of ending slavery the discerning viewer will also be left with the challenges that the nation still faces. For some it may even serve as a reminder of the level of violence witnessed in the north as tens of thousands of southern blacks made their way to cities at the turn of the century in pursuit of a better life.

![]()

Kevin also questioned a scene at the very beginning of the film, dialogue between Lincoln and two Union soldiers, one black and one white, that seemed forced and contrived — “ridiculous.” Bjorn Skaptason counters, arguing that the scene, although fictional, is both historically plausible and sets up the larger conflict of the film’s storyline:

![]()

I have seen the film just once, like you. I might have taken more away from that opening scene, though. I think the battle scene is clearly the U.S.C.T. soldier describing his experience as part of the 2nd Kansas (Colored) in the battle of Jenkins Ferry, Arkansas. Ken is right that there was a hand-to-hand fight there for a couple of guns during a driving rainstorm in a muddy, plowed field. The Second Kansas took no prisoners in that engagement. The soldier then goes on to describe a reasonable transfer scenario wherein he joined the 116th USCT in Kentucky, and now he is standing in front of the commander-in-chief at a wharf in Washington, D.C. Further, the infantryman is in company with a cavalryman who identifies himself as part of a Connecticut Volunteer regiment (the 5th?). That individual is much more aggressive in challenging Lincoln on the failures of his administration. The infantryman is visibly annoyed by this. There is rich subtext here for historians. The infantryman is a Kansas freedman, escaped from bondage in Missouri, and fighting to destroy slavery. He is thrilled to meet the Great Emancipator. The cavalryman is probably a free born New Englander, obviously well-educated, and committed to a mission of equality that Lincoln is distinctly failing at. He will not let Lincoln get away with empty promises and half measures. The unspoken conflict between these two soldiers, played out in annoyed sideways glances, foreshadows the conflict of the movie – a conflict between overthrowing slavery on one hand and establishing equal rights on the other. They aren’t the same thing, they weren’t perceived as such at that time, and the movie sets up that nuanced view of the situation in the first scene.

![]()

Finally, it’s worth everyone’s time to read Harold Holzer’s column over at The Daily Beast, “What’s True and False in ‘Lincoln’ Movie.” Holzer, who served as an historical consultant for the film, was concerned about getting grief for historical errors in the picture. That changed last week, he said, when the director gave the Dedication Day Address at the National Soldier’s Cemetery in Gettysburg:

![]()

For a few weeks, I haven’t known quite how I would respond. But yesterday at Gettysburg, Steven Spielberg provided the eloquent answer. “It’s a betrayal of the job of the historian,” he asserted, to explore the unknown. But it is the job of the filmmaker to use creative “imagination” to recover what is lost to memory. Unavoidably, even at its very best, “this resurrection is a fantasy … a dream.” As Spielberg neatly put it, “one of the jobs of art is to go to the impossible places that history must avoid.” There is no doubt that Spielberg has traveled toward an understanding of Abraham Lincoln more boldly than any other filmmaker before him. Besides, those soldiers who recite the Gettysburg Address may simply represent the commitment of white and black troops to fight together for its promise of “a new birth of freedom.” Mary Lincoln’s presence in the House chamber may be meant to suggest how intertwined the family’s private and public life have become. The image of “Old Tippecanoe” Harrison in Lincoln’s office may be an omen for his own imminent death in office. In pursuit of broad collective memory, perhaps it’s not important to sweat the small stuff. From time to time, even “Honest Abe” himself exaggerated or dissembled in pursuit of a great cause. Just check out the shady roads he took to achieve black freedom as “imagined” so dazzlingly in the movie. . . . Sometimes real history is as dramatic as great fiction. And when they converge at the highest levels, the combination is unbeatable.

![]()

If you haven’t yet, go see this movie. You won’t be disappointed.

______________Image: Lincoln (Daniel Day-Lewis) and his cabinet are briefed on the plans for the bombardment of Fort Fisher by Secretary of War Stanton (standing left, played by Bruce McGill).

Spielberg Lays Bare the Ugly Politics of Emancipation

Smithsonian.com has a long feature by Roy Blount, Jr. on the making of Spielberg’s Lincoln, in particular the way it challenges common tropes about the 16th president. The film focuses on Lincoln’s efforts to pass the 13th Amendment in early 1865. Blount’s entire piece is worth reading, but I’m especially impressed that Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner seemingly pull no punches when it comes to the pervasive, casual bigotry of 19th century Americans and the hard-nosed, carefully-crafted political maneuvering necessary to pass such a measure in 1865:

[The film] provides no golden interracial glow. The n-word crops up often enough to help establish the crudeness, acceptedness and breadth of anti-black sentiment in those days. A couple of incidental pop-ups aside, there are three African-American characters, all of them based reliably on history. One is a White House servant and another one, in a nice twist involving Stevens, comes in almost at the end. The third is Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln’s dressmaker and confidante. Before the amendment comes to a vote, after much lobbying and palm-greasing, there’s an astringent little scene in which she asks Lincoln whether he will accept her people as equals. He doesn’t know her, or her people, he replies. But since they are presumably “bare, forked animals” like everyone else, he says, he will get used to them. Lincoln was certainly acquainted with Keckley (and presumably with King Lear, whence “bare, forked animals” comes), but in the context of the times, he may have thought of black people as unknowable. At any rate the climate of opinion in 1865, even among progressive people in the North, was not such as to make racial equality an easy sell. In fact, if the public got the notion the 13th Amendment was a step toward establishing black people as social equals, or even toward giving them the vote, the measure would have been doomed. That’s where Lincoln’s scene with Thaddeus Stevens [Tommy Lee Jones, above] comes in. _____ Stevens is the only white character in the movie who expressly holds it self-evident that every man is created equal. In debate, he vituperates with relish—You fatuous nincompoop, you unnatural noise!—at foes of the amendment. But one of those, Rep. Fernando Wood of New York, thinks he has outslicked Stevens. He has pressed him to state whether he believes the amendment’s true purpose is to establish black people as just as good as whites in all respects. You can see Stevens itching to say, “Why yes, of course,” and then to snicker at the anti-amendment forces’ unrighteous outrage. But that would be playing into their hands; borderline yea-votes would be scared off. Instead he says, well, the purpose of the amendment— And looks up into the gallery, where Mrs. Lincoln sits with Mrs. Keckley. The first lady has become a fan of the amendment, but not of literal equality, nor certainly of Stevens, whom she sees as a demented radical. The purpose of the amendment, he says again, is — equality before the law. And nowhere else. Mary is delighted; Keckley stiffens and goes outside. (She may be Mary’s confidante, but that doesn’t mean Mary is hers.) Stevens looks up and sees Mary alone. Mary smiles down at him. He smiles back, thinly. No “joyous, universal evergreen” in that exchange, but it will have to do. Stevens has evidently taken Lincoln’s point about avoiding swamps. His radical allies are appalled. One asks whether he’s lost his soul; Stevens replies, mildly, that he just wants the amendment to pass. And to the accusation that there’s nothing he won’t say toward that end, he says: Seems not.

![]()

If Blount’s recounting of the film is accurate, then this movie may end up doing a tremendous service to the public’s understanding of that pivotal moment in American history. It may well do for the public’s understanding of Lincoln what Glory did, a generation ago, for recognition of the role African American soldiers played in that conflict. The popular image of Lincoln pure and unblemished saint-on-earth has always been a false and ultimately damaging one, as much as the “Marble Man” has been for Lee. Lincoln’s contemporaries didn’t see him that way. For all that Lincoln was branded as a radical abolitionist in the South, real abolitionists knew he was not one of them. According to Blount, Stevens called Lincoln “the capitulating compromiser, the dawdler,” and even Frederick Douglass, who overcame a deep mistrust of Lincoln and the Republicans in the winter of 1860-61 to become one of the president’s strongest allies and supporters, understood that Lincoln was a man who retained his own biases, yet constantly challenged himself to move beyond those. Lincoln was also a man who, regardless of his personal beliefs, had to work (like all presidents before and since) within the constraints of the political realities of the day. It was Lincoln’s willingness to work the political angle — to cajole, to flatter, to intimidate, to compromise when he had to — that allowed him to accomplish things that a firebrand like Stevens never could have, no matter how righteous his cause. As Blount says, “Stevens was a man of unmitigated principle. Lincoln got some great things done.”

There’s a saying that’s been thrown around quite a bit in the last few years, “don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.” In other words, don’t pass up an opportunity to get most of what you want, for the sake of not being able to get everything you want. That’s good advice now, and it was undoubtedly a notion Lincoln — smart lawyer and brilliant politician that he was — would have agreed with.

When the movie hits theaters in a couple of weeks, I’m sure it will be lazily denounced in some quarters as just so much Lincoln mythologizing. A few more industrious folks will likely cite scraps of dialogue from the film to “prove” that ZOMG those Yankees were racists!. They already seem to be priming themselves to denounce it as a failure if it fails to smash every box-office record, ever. In truth, though, I think they may have a lot more to worry about with this film than the prospect of it being a big-screen affirmation of the caricatured, saintly Lincoln. If the movie is anything like Blount claims it is, it will depict Lincoln and those around him as gifted, resolute but often flawed and complex mortals who struggled and bickered and fought, and eventually accomplished great things — things like the 13th Amendment that seem so obviously right now, but were anything but assured then. If the audience takes away that understanding of the events surrounding the close of the war, it will do far more good than any exercise in hagiography might.

I can’t hardly wait.

___________

UPDATE, October 29: Over at Civil War Talk, a member asks why Frederick Douglass is not depicted in the film.

It’s a great question, and I don’t know the answer. But there’s no point in having a blog if one can’t speculate a little, so here goes:

It may be in part because Douglass was not physically present during the events depicted in the main part of the film, which focuses on passage of the 13th Amendment and the Hampton Roads Conference, which took place in January and early February 1865. I believe Douglass resided in Rochester, New York during the entire period of the war, and as nearly as I can tell, Douglass and Lincoln only met face-to-face on three occasions: in August 1863, when Douglass met with the president to urge him to equalize the pay between white and black Union soldiers; at the White House a year later, when Lincoln summoned Douglass to reaffirm his (Lincoln’s) commitment to ending slavery and to ask Douglass to use his connections to get as many enslaved persons within Union lines in the event he lost the election that fall and a new administration would end the war before decisively defeating the Confederacy; and in early March 1865, when Douglass was ushered into the president’s presence briefly at an inaugural reception to congratulate him on his reelection. This last event, though close to the time frame of the Spielberg film, was not really a substantive meeting that would have particular bearing on the story of the film.

So if my understanding of the structure of the movie is correct, there’s an easy (if not especially satisfying) explanation for his absence from the screen. What will be most interesting to see is whether Douglass’ presence is nonetheless felt in the film — if his words, his writings, his agitating — show up in the script, in allusions by other characters, in the dialogue, or elsewhere. (Elizabeth Keckley’s character [right] would be the obvious opportunity to do this, film-wise, as she admired Douglass and wrote of his being brought to meet the president in March 1865.) The real Frederick Douglass didn’t attend cabinet meetings or negotiations with representatives of the Confederate government aboard River Queen, but he nonetheless exerted a profound influence behind the scenes in both the decision to enlist black troops for the Union and in the struggle to make emancipation permanent in the closing months of the war. If Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner can pull that off — making Douglass and his influence a character in the film without his actually being in the film — that will be remarkable.

So if my understanding of the structure of the movie is correct, there’s an easy (if not especially satisfying) explanation for his absence from the screen. What will be most interesting to see is whether Douglass’ presence is nonetheless felt in the film — if his words, his writings, his agitating — show up in the script, in allusions by other characters, in the dialogue, or elsewhere. (Elizabeth Keckley’s character [right] would be the obvious opportunity to do this, film-wise, as she admired Douglass and wrote of his being brought to meet the president in March 1865.) The real Frederick Douglass didn’t attend cabinet meetings or negotiations with representatives of the Confederate government aboard River Queen, but he nonetheless exerted a profound influence behind the scenes in both the decision to enlist black troops for the Union and in the struggle to make emancipation permanent in the closing months of the war. If Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner can pull that off — making Douglass and his influence a character in the film without his actually being in the film — that will be remarkable.

I can’t hardly wait.

___________

Anticipating Lincoln

On Sunday evening 60 Minutes did a story on Steven Spielberg and his upcoming film, Lincoln. Much of the interview focused on the way Spielberg’s childhood and relationship with his parents, particularly his father, has been reflected in his films. That’s pretty interesting in its own right, but I do wish more time had been spent on Lincoln.

As a filmmaker, Spielberg has never been known for complex characterizations or ambiguous moral messages. (Or realism.) This film is decidedly different in tone, something the director himself acknowledges. It’s not aimed at the summer blockbuster crowd:

Lesley Stahl: There’s not a lot of action. There’s no Spielberg special effects. Steven Spielberg: Right. Lesley Stahl: It’s a movie about process and politics. Have you ever done a movie even remotely– Steven Spielberg: Never. Like this? Lesley Stahl: Not even close. Steven Spielberg: Never. No. I knew I could do the action in my sleep at this point in my career. In my life, the action doesn’t hold any– it doesn’t attract me anymore. Narrator: With only one brief battle scene, the movie’s more like a stage play with lots of dialog as Lincoln cajoles and horse trades for votes.

![]()

Spielberg and his team made a pretty fascinating decision, to focus the film on the last months of Lincoln’s life and his efforts to pass the 13th Amendment, that abolished slavery throughout the United States. The Union military victory was clearly in sight at that point, and Lincoln was trying to make permanent the de facto emancipation brought about by the Emancipation Proclamation and the advance of Federal armies across the South. As we’ve noted before, Lincoln’s commitment to ending chattel bondage permanently by embedding it in the Constitution is evidenced by the fact that he signed the original text of the amendment as passed by both houses of Congress, even though the president has no formal role in approving or endorsing constitutional amendments. The Emancipation Proclamation gets lots of attention, but is also too often misrepresented as the be-all and end-all of emancipation, when it was (as any serious historian will tell you) a temporary, limited, wartime measure, a single, important milestone on the path to real, permanent emancipation. (A path, by the way, that begins with Spoons Butler’s 1861 “contraband” policy at Fort Monroe.) The Emancipation Proclamation is not Lincoln’s legacy; the 13th Amendment rightly is.

Then there’s this, which is an interesting approach, although not one I’m sure I agree with:

![]()

Narrator: Although Spielberg took great pains to be historically accurate, he made what some will see as a curious exception in this scene. Steven Spielberg: Some of the Democrats that were voting against the [13th] Amendment, we changed their actual names. So if you go through the names that we call out on the vote, you’re not going to find a lot of those names that conform to history. And that was in deference to the families.

![]()

All of this effort and nuance will likely be wasted on the True Southron™ crowd, who are already carping about the film’s likely omission of black Confederates and predicting its dismal failure at the box office. I suspect most of them will refuse to watch the movie, though that will hardly stop them from complaining about its content, real or imagined. While history buffs will be arguing about details — whether this character actually said that, or whether such-and-such scene really happened or is a composite of several actual events — the Southrons will be more vaguely angered that the film exists at all, and that it depicts Lincoln as genuinely committed to ending slavery, willing to push the boundaries of his office and the political landscape to as much as he dared to accomplish that goal. That notion is an anathema to the Southrons, because it puts Lincoln, whatever else his faults, squarely on the right side of the great moral issue facing Americans in the 19th century. Instead they will rehash Lincoln’s casual bigotry against African Americans (true, although almost universal among white Americans in that day), and his willingness to consider voluntary recolonization of freedmen to Africa — an idea that long predated Lincoln’s public life and long survived him, as well. These are, after all, the people who can say with a straight face that Lincoln was “a bigger racist than I ever knew,” and more deserving of moral condemnation than their own ancestors who actually owned slaves. As I wrote several months back,

![]()

Confederate apologists often point to these ugly examples and say, “Lincoln believed so-and-so, ” or “Lincoln said such-and-such.” They do this reflexively, as a means of deflecting criticism of slavery in the the South. Such mentions of Lincoln are often narrowly true, but they miss the larger, and much more important, truth. . , which is that Lincoln himself changed and grew over time. The president who told “darkey” jokes also had Frederick Douglass as a visitor to the White House in 1863, the first African American to enter that building not as a servant or laborer, but as a guest. The president who’d said he would be willing not to free a single slave if it would preserve the Union also asked Douglass, in the summer of 1864, to use his contacts to get as many slaves into Union lines as he could before that fall’s presidential election, which Lincoln fully expected to lose. The chief executive who had toyed with the idea of re-colonizing former slaves back to Africa publicly suggested, just days before his death, that suffrage should be extended to at least some freedmen, specifically those who’d served in the Union army.

![]()

Lincoln Derangement Syndrome is very real, and Spielberg’s film is certain to push some folks over the edge. So don’t expect much effort from the Confederate Heritage™ crowd to take the movie on its own terms, or to acknowledge anything positive about the 16th president — just a lot of vague complaining about “PC Hollywood” or the “Lincoln myth,” and so on, without much reference to the specific content of the film itself.

For the rest of us, though, it’s looking like this is going to be a film that delves into a part of Lincoln’s life that’s never been brought to the big screen before. I sure it will give historians and bloggers much both to praise and criticize in the coming weeks. My hope is that, like Glory, Lincoln will be a film that, while containing inevitable small historical inaccuracies, will nonetheless tell a greater true story, will loom large in the general public’s understanding of the conflict and inspire a renewed interest in it.

I can’t hardly wait.

_____________

Was Lincoln a Flip-Flopper?

Tuesday morning NPR had an interesting segment on David Hebert Donald’s Lincoln, the first in a new series of interviews that discuss presidents from the past in the context of the 2012 presidential campaign. Participating in the discussion were three other prominent Lincoln biographers, Eric Foner (right), Doris Kearns Goodwin, and Andy Ferguson. As you might guess, with those panelists the discussion was less about Donald’s work than it was about those three making the key points they wanted to make — which is just fine with me. You can listen to the piece here, or read the transcript here.

Tuesday morning NPR had an interesting segment on David Hebert Donald’s Lincoln, the first in a new series of interviews that discuss presidents from the past in the context of the 2012 presidential campaign. Participating in the discussion were three other prominent Lincoln biographers, Eric Foner (right), Doris Kearns Goodwin, and Andy Ferguson. As you might guess, with those panelists the discussion was less about Donald’s work than it was about those three making the key points they wanted to make — which is just fine with me. You can listen to the piece here, or read the transcript here.

I particularly liked this exchange between the interviewer, Steve Inskeep, and Eric Foner, whose book on Lincoln and the question of slavery, The Fiery Trial, won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize in History:

INSKEEP: If it were up to you, each of you, if you were presidential speechwriters, how would you want candidates to think of Lincoln, deploy Lincoln when they’re talking about him today? FONER: You know, I would love to see a candidate – I don’t care which party we’re talking about – forthrightly say: I have changed my mind about this. That’s what Lincoln did during the Civil War. He changed his mind over and over again. He didn’t change his core beliefs. Lincoln was a flip-flopper, if you want to use the terminology of modern politics. But we don’t seem to allow our politicians to do that anymore. INSKEEP: Andrew Ferguson, you’re smiling. FERGUSON: It’s partly because politicians won’t let their speechwriters talk that way. I don’t think that Dr. Foner should wait for a phone call from any political campaign because… FONER: I’m not holding my breath.

I get what Foner’s saying, but he does his own scholarship a serious disservice by labeling Lincoln “a flip-flopper.” Lincoln knew his own mind, and was from early adulthood (if not earlier) opposed to slavery, personally. That never changed. But neither was it a priority for him as a public official, either. He was not, regardless of how he was depicted by the fire-eaters in the run-up to the 1860 election, a secret abolitionist bent on overturning the institution where it already existed. He himself held attitudes and spoke in terms that would be deeply offensive today. He told an occasional “darkey” joke. He explained once that, in his view, whites and African Americans could not peaceably live together. He considered any number of schemes in considering the “Negro problem,” including voluntary recolonization to Africa. (Colonization was an idea, one should note, that long pre-dated Lincoln and long survived him, as well.)

Confederate apologists often point to these ugly examples and say, “Lincoln believed so-and-so, ” or “Lincoln said such-and-such.” They do this reflexively, as a means of deflecting criticism of slavery in the the South. Such mentions of Lincoln are often narrowly true, but they miss the larger, and much more important, truth that lies at the core of Foner’s (and many others’) work, which is that Lincoln himself changed and grew over time. The president who told “darkey” jokes also had Frederick Douglass as a visitor to the White House in 1863, the first African American to enter that building not as a servant or laborer, but as a guest. The president who’d said he would be willing not to free a single slave if it would preserve the Union also asked Douglass, in the summer of 1864, to use his contacts to get as many slaves into Union lines as he could before that fall’s presidential election, which Lincoln fully expected to lose. The chief executive who had toyed with the idea of re-colonizing former slaves back to Africa publicly suggested, just days before his death, that suffrage should be extended to at least some freedmen, specifically those who’d served in the Union army.

I personally don’t have a lot of use for political flip-floppers, whose deeply-held convictions change according to the latest Rasmussen polls. But neither do I have a lot of use for those who are unwilling to learn, to grow, and to change their minds when the circumstances warrant. That latter group are the ideologues, and while they may shape the debate over public policy, they end up accomplishing very little themselves. Successful leaders are those who are able to distinguish between what they would prefer and what they can accomplish, and push hard for the latter. Idealism has its role, but pragmatism gets the job done. The perfect, the saying goes, must not be the enemy of the good.

Presidents don’t have the luxury of being all-or-nothing ideologues: not in 2012, or in 1862. They are expected to lead, but can only lead where the country — or at least a large part of the country — is willing to follow. Wholesale emancipation — regardless of how much Lincoln might or might not have wanted it at the time — was never a possibility in 1861. It was not a priority for Lincoln, nor was it a priority for the rest of the country. But by the third year of the conflict, it was an established war aim for the Union. Lincoln understood, as well, that his Emancipation Proclamation was a wartime expedient, a stop-gap measure that would not likely hold up once the conflict ended, so he backed the 13th Amendment, passed by the House of Representatives and Senate weeks before his own death.

Flip-floppers chose the positions they do because they believe those position will make them popular. And they do, for a time, before the public catches on to the fact that they’re being played. There are many words that might describe Lincoln during his presidency, but “widely popular” isn’t generally one of them. He might not have won the presidency in the first place had not some Southern states, including my own, kept him off the ballot altogether in 1860; he only took 55% of the popular vote in 1864, when an ultimate Union victory was clearly visible on the horizon. Lincoln probably would have been a far more popular and successful politician in his own day if he had paid more attention to public opinion, and chosen more popular positions. He would have had a much easier time of it, but American history would look very, very different. And not in a good way.

________________

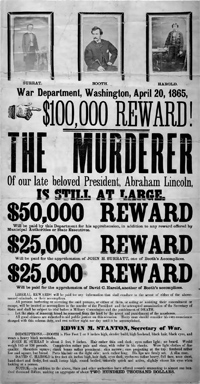

“. . . the madman Booth”

April 15 is the anniversary of the death of Abraham Lincoln. There may be no other event in American history that’s inspired more what-ifs than the question, “what if Lincoln had served a full second term?”

April 15 is the anniversary of the death of Abraham Lincoln. There may be no other event in American history that’s inspired more what-ifs than the question, “what if Lincoln had served a full second term?”

Earlier today I read a post elsewhere that made a passing reference to “the madman Booth.” This, I think, lets him off too easy, as though he were a mere lunatic no one could have stopped, no on could have prevented, and no one could have predicted.

This is wrong.

Booth was not a madman, a random nutter, acting at the behest of voices in his head. His motivations and self-justifications were firmly grounded in the tumultuous events of the time, rather than a fantasy that existed only in his own mind. While the actor was undoubtedly unhinged and irrational on some levels, he didn’t meet the criminal justice system’s definition of insane, then or now. He plotted in considerable detail. He successfully organized a crew — misfits and hangers-on though they were — and held them together for an extended period. He pulled together complex plans for kidnapping and then murder that, while impractical in retrospect, were nonetheless specific and detailed. He convinced two other men to attempt murder as well, though one lost his nerve at the last moment. He had an extended network of sympathizers and supporters who, if not actively involved in the assassination plot, certainly knew of his grumbling and scheming and did nothing to impede him. One wonders, when they first heard that Lincoln had been shot, how many people immediately thought of John Wilkes Booth?

Above all, he genuinely believed that his actions were directly supporting the Confederate war effort, or (after Appomattox) exacting its revenge, and expected his name to go down in history as a great Southern hero. Sadly for our country, South and North alike, some people still see him that way.

What are your thoughts on Booth, his conspirators, and the Lincoln assassination?

_____________

A New President, and an Ambivalent Abolitionist

The fire-eaters across the South saw the election of Abraham Lincoln as the beginning of the end of slavery in the United States. Although the Republicans were careful not to challenge the institution where it already existed, for many in the South, the new administration was seen as a harbinger all the slaveholding class’ worst fears — economic turmoil, political upheaval and collapse of a carefully-crafted legal and social structure centered on race. The fire-eaters worked themselves up into a fury, convincing themselves and many of their contemporaries that Lincoln himself was a radical abolitionist, bent on nothing less than the complete and utter eradication of slavery and establishing full social and racial equality between blacks and whites.

Actual abolitionists knew better, and were largely ambivalent about Lincoln’s candidacy in 1860. Some supported it, reluctantly, as the best practical alternative, while others held a convention that summer to nominate their own presidential candidate as a show of protest. Frederick Douglass eventually came to embrace Lincoln as an ally, but even after the election, Douglass still considered the Republicans a sort of least-bad option, and expressed concern that the Republicans’ tolerance of slavery where it already existed would undermine, and possibly destroy, the movement to eliminate slavery everywhere in the country:

Actual abolitionists knew better, and were largely ambivalent about Lincoln’s candidacy in 1860. Some supported it, reluctantly, as the best practical alternative, while others held a convention that summer to nominate their own presidential candidate as a show of protest. Frederick Douglass eventually came to embrace Lincoln as an ally, but even after the election, Douglass still considered the Republicans a sort of least-bad option, and expressed concern that the Republicans’ tolerance of slavery where it already existed would undermine, and possibly destroy, the movement to eliminate slavery everywhere in the country:

Nevertheless, this very victory threatens and may be the death of the modern Abolition movement, and finally bring back the country to the same, or a worse state, than Benj. Lundy and Wm. Lloyd Garrison found it thirty years ago. The Republican party does not propose to abolish slavery anywhere, and is decidedly opposed to Abolition agitation. It is not even, by the confession of its President elect, in favor of the repeal of that thrice-accursed and flagrantly unconstitutional Fugitive Slave Bill of 1850. It is plain to see, that once in power, the policy of the party will be only to seem a little less yielding to the demands of slavery than the Democratic or Fusion party, and thus render ineffective and pointless the whole Abolition movement of the North. The safety of our movement will be found only by a return to all the agencies and appliances, such as writing, publishing, organizing, lecturing, holding meetings, with the earnest aim not to prevent the extension of slavery, but to abolish the system altogether.

It was as true one hundred fifty years ago as it is today; we have an unfortunate tendency to reduce those movements and political figures we oppose to simplistic caricatures, and to assume that all those actors share similar motivations and goals. They don’t, and sometimes they don’t even fully trust each other.

___________

Update: Though Douglass worried about the victory of Lincoln and the Republicans, he welcomed South Carolina’s secession, bringing with it as it did a constitutional crisis that, in his view, must ultimately decide the matter of slavery. As historian David Blight points out in a new editorial in the New York Times, “Cup of Wrath and Fire,” Douglass “heaped scorn on the Palmetto State’s rash act, but he also relished it as an opportunity. He all but thanked the secessionists for ‘preferring to be a large piece of nothing, to being any longer a small piece of something.'”

The “Insolence of Epaulets”

A telling anecdote about George McClellan, from Goodwin’s Team of Rivals:

On Wednesday night, November 13, [1861] Lincoln went with [Secretary of State] Seward and [Lincoln’s secretary John] Hay to McClellan’s house. Told that the general was at a wedding, the three waited in the parlor for an hour. When McClellan arrived home, the porter told him the president was waiting, but McClellan passed by the parlor room and climbed the stairs to his private quarters. After another half hour, Lincoln again sent word that he was waiting, only to be informed that the general had gone to sleep. Young John Hay was enraged. “I wish here to record what I consider a portent of evil to come,” he wrote in his diary, recounting what he considered an inexcusable “insolence of epaulets,” the first indicator “of the threatened supremacy of the military authorities.” To Hay’s surprise, Lincoln “seemed not to have noticed it specially, saying it was better at this time not to be making points of etiquette & personal dignity.” He would hold McClellan’s horse, he once said, if a victory could be achieved.

McClellan got away with this, of course, because Rolling Stone wouldn’t begin publication for another 106 years. McClellan’s snub, brazen and explicit as it was, occurred in front of a just a few witnesses, none of whom made it public at the time, so the president had the option of ignoring it.

One wonders, though, if he later wished he hadn’t.

Update, July 1: Dimitri Rotov isn’t sure this incident actually happened, as it comes from only a single source, highly partisan to Lincoln. Fair enough.

H/t Smeather’s Tavern.

9 comments