In Search of the Black Confederate Unicorn

Many of you will have heard of the proposal by two State Representatives in South Carolina to put up a monument at the State House in Columbia honoring African-American Confederate war veterans. They have apparently been surprised to discover that serious historians who’ve actually examined the primary source records are telling them that there essentially were none, at least the way the bill’s sponsors seem to think there were. I suppose that’s what happens when you get your understanding of history from Facebook.

I don’t have much else to say about this, except to point to this short comment by Josh Marshall over at Talking Points Memo, wherein one finds this gem of a line:

The specifics of this story challenge my ability to pry apart pure bad faith… from its second cousin, willful self-delusion.

I think I’m going to have a lot of opportunity to quote that line in the future.

Y’all have a great 2018, now!

______

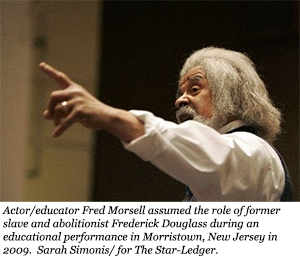

Frederick Douglass’ Black Confederate

A few weeks ago Harvard historian John Stauffer published an essay in The Root entitled, “Yes, There Were Black Confederates. Here’s Why.” Stauffer’s essay was largely an expansion of a talk he gave in 2011, which itself reflected little more research than Googling around the web for well-worn anecdotes. Stauffer’s Root piece was mostly panned by historians who have closely studied the “black Confederate” theme, particularly by my blogging colleagues Kevin Levin and Brooks Simpson. Both continued that discussion through follow-up posts. I wrote about it as well, pointing out that Stauffer identified one of Frederick Douglass’ sources in 1861 as an African American man who claimed to have seen “one regiment [at Manassas] of 700 black men from Georgia, 1000 [men] from South Carolina, and about 1000 [men with him from] Virginia, destined for Manassas when he ran away.” Unfortunately Stauffer appears not to have followed up on the source of that quote, which actually appeared in the Boston Daily Journal and Evening Transcript newspapers in February 1862, roughly six months after Douglass wrote about them in his newsletter.

A few weeks ago Harvard historian John Stauffer published an essay in The Root entitled, “Yes, There Were Black Confederates. Here’s Why.” Stauffer’s essay was largely an expansion of a talk he gave in 2011, which itself reflected little more research than Googling around the web for well-worn anecdotes. Stauffer’s Root piece was mostly panned by historians who have closely studied the “black Confederate” theme, particularly by my blogging colleagues Kevin Levin and Brooks Simpson. Both continued that discussion through follow-up posts. I wrote about it as well, pointing out that Stauffer identified one of Frederick Douglass’ sources in 1861 as an African American man who claimed to have seen “one regiment [at Manassas] of 700 black men from Georgia, 1000 [men] from South Carolina, and about 1000 [men with him from] Virginia, destined for Manassas when he ran away.” Unfortunately Stauffer appears not to have followed up on the source of that quote, which actually appeared in the Boston Daily Journal and Evening Transcript newspapers in February 1862, roughly six months after Douglass wrote about them in his newsletter.

Douglass was making the rounds as a speaker that winter, and the man Stauffer cited as Douglass’ source had appeared with him at an Emancipation League at the Tremont Temple on February 5, 1862. That address must have given Douglass great satisfaction, as just fourteen months previously Douglass and other abolitionists had been forcibly ejected from that same venue on orders of Boston’s mayor.

But, as so often happens with historical research, nailing down the answer to one question raises several others. In this case, who was the “fugitive black man from a rebel corps”[1] who gave the account of thousands of African American troops, organized into whole regiments, at Manassas? My colleague Dan Weinfeld, author of The Jackson County War: Reconstruction and Resistance in Post-Civil War Florida, decided to take on that question. He began by tracking down other accounts of Douglass’ speeches from this period as reproduced in Douglass’ Monthly newsletter. Sure enough, the March 1862 issue included not only the text of Douglass’ addresses, but also summaries of the remainder of the program. On February 12, one week after his speech in Boston, Douglass presented his program at Cooper Union (emphasis added):

At 8 o’clock, the [body] of the hall was nearly filled with an intelligent and respectable looking audience – The exercises commenced with a patriotic song by the Hutchinsons, which was received with great applause. The Rev. H. H. Garnett opened the meeting stating that the black man, a fugitive from Virginia, who was announced to speak would not appear, as a communication had been received yesterday from the South intimating that, for prudential reasons, it would not be proper for that person to appear, as his presence might affect the interests and safety of others in the South, both white persons and colored. He also stated that another fugitive slave, who was at the battle of Bull Run, proposed when the meeting was announced to be present, but for a similar reason he was absent; he had unwillingly fought on the side of Rebellion, but now he was, fortunately where he could raise his voice on the side of Union and universal liberty. The question which now seemed to be prominent in the nation was simply whether the services of black men shall be received in this war, and a speedy victory be accomplished. If the day should ever come when the flag of our country shall be the symbol of universal liberty, the black man should be able to look up to that glorious flag, and say that it was his flag, and his country’s flag; and if the services of the black men were wanted it would be found that they would rush into the ranks, and in a very short time sweep all the rebel party from the face of the country.[2]

Although the man who “had unwillingly fought on the side of Rebellion” is not identified, evidence strongly suggests it was John Parker, the escaped slave who had served a Confederate artillery battery at Manassas. Just a few pages after the passage above, the Douglass Monthly reprints Parker’s “A Contraband’s Story” that had appeared earlier in the Reading [Pennsylvania] Journal. As Kate Masur noted in a New York Times Disunion essay in 2011, Parker had arrived in New York at the end of January 1862, where he was interviewed again about the Battle of Bull Run and Confederate losses there.[3]

Notice in the Rochester, New York Union & Advertiser, February 12, 1862, announcing Douglass’ speech that night at Cooper Union, promising an appearance by “a rebel negro, in his regimentals, a deserter from Dixie.”[4]

Additional material published at the time strongly indicates that the man announced to appear with Douglass was, in fact, John Parker. He was speaking in the same area at the same time as Douglass. For example, on February 19, one week after the Cooper Union event, Parker was the featured speaker at a Presbyterian church across the Hudson River in Newark, New Jersey. “Parker was hired by his master to the rebels at the breaking out of the rebellion,” according to the Newark Daily Advertiser, and “has worked at Winchester, Richmond, and Manassas, and is in possession of facts and incidents which the public are invited to listen to.”[5]

Parker told his story to many people, including giving an extended interview to the New York Evening Post. Parker’s account of Manassas is vivid but badly muddled; when asked how many black persons there were “in the [Confederate] army there, he asserts that there were “one whole regiment of free colored persons, and two regiments slaves among the white regiments, one company to each.” A few paragraphs later, though, he claims that the number of black Confederate regiments at Manassas had since increased to “twelve regiments of negroes in the vicinity of Bull Run and Manassas Junction” (emphasis original). These twelve regiments, Parker again states, “are distributed one company in a regiment,” a claim that makes no sense at all.[6] A normal infantry regiment of the time consisted of ten companies of about a thousand men in aggregate; Parker’s description is profoundly unclear in terms of organization and numbers of men.

The rest of Parker’s account of First Manassas equally questionable. In his New York Evening Post interview he claimed to be “sartin” (certain) that there were 3,600 Confederate dead, and 4,000 Federals. His estimates were off by an order of magnitude; the actual numbers were around 387 and 460, respectively. He gave the number of Confederate wounded as about 5,400, which is several times the actual number.

Of course, Parker was not a trained soldier, and none of the press accounts during his speaking engagement explicitly characterize him as such. Throughout his interview with the Evening Post, Parker made it clear that while he served a Confederate gun in action, neither his sympathies nor those of his fellows lay with the Confederate cause. In his earlier interview with the Reading Journal, reproduced in the Douglass Monthly in March, Parker asserted that “we would have run over to their side but our officers would have shot us if we had made the attempt.” He claimed that “our masters tried all they could to make us fight. They promised to give us our freedom and money besides, but none of us believed them, we only fought because we had to.” To the New York Evening Post, he claimed that a slave from Alabama had been assigned by his master to serve as a sharpshooter, and in that capacity killed three Federal pickets. When he himself was killed soon after, it “was a source of general congratulation among the negroes [sic.], as they do not intend to shoot the white soldiers.”[7]

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly, May 10, 1862, showing Confederate slaves being forced to serve a cannon at gunpoint. John Parker claimed he and other slaves were put in a similar position at the Battle of First Manassas, saying that “we would have run over to [the Federals’] side but our officers would have shot us if we had made the attempt.”

Parker said that he and the other slaves manning the guns adjusted the elevating screws to fire over the heads of Union troops during the battle at Manassas. Recounting a prayer of thanksgiving given after the Confederate victory, one full of “southern braggadocio and bombast,” Parker said that “the colored people did not believe him, nor that the Lord was on that side.” Parker predicted that many slaves would continue to serve the Confederate cause, for fear that “the Lord was on the side of the South, and that they had got to be slaves always.” As for himself, Parker said, he would turn his artillery piece on Confederate forces and “could do it with pleasure,” though he dreaded the prospect of ever being in another battle again.[8]

Was Parker exaggerating his experiences for an audience that was eager to believe the worst about the Confederates? It’s certainly possible. Did Douglass, who appeared with Parker on stage and published his story in the Douglass Monthly, have doubts about the man’s account? We cannot know. But whether he was telling exaggerated stories about First Manassas or not, the best evidence of Parker’s feeling toward the Confederacy lay in the fact that he began his speaking tour soon after learning that his wife and two youngest children – a son, eight, and a daughter, six — had successfully escaped to Union lines and were now on free soil, where they were safe from any retaliation that might occur as a result of his speaking. Two older sons, seventeen and fourteen, remained in the South, the elder as an officer’s servant and the younger, sold off to another owner six months before the war. (Parker gives his owner’s name as “Colonel Thomas Griggs,” who was likely William T. Griggs [1828-83], who was a Lieutenant Colonel in the Virginia Militia but served during the war as an enlisted soldier in the Fifteenth Virginia Cavalry.) At the time of his interview Parker had been informed that his wife and two younger children had arrived in New York but had not been able to link up with them; when they were reunited, he said, he hoped they would all continue on to Canada because he was still “not quite sure of his safety here.”[9]

As Glenn Brasher points out in his 2012 volume, The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom, Parker’s speaking tour and that of another former slave, William Davis, gave a boost to both the cause of emancipation and for the enlistment of black soldiers in the U.S. military. (Davis also spoke at Cooper Union, on January 15, 1862, four weeks before Douglass. But Davis had come from Fortress Monroe, and did not claim to have present at First Manassas, or to have served the Confederates in any military capacity.) Thousands of people had heard Parker, Davis, or Douglass speak on the subject, and many thousands more read about it in the New York and Boston area papers. “Allegations that Southerners were coercing African Americans into combat continued to be a regular feature in the speeches and editorials of emancipationsists,” Brasher writes. “In pushing for both emancipation and the recruitment of black troops, the abolitionist newspaper Principia maintained that the Confederates ‘have been fighting in close companionship with negroes, from the beginning!’ Southern blacks, the paper claimed, ‘are regularly drilled for the service. And the proportion of negro soldiers in increasing.’”[10]

Douglass himself went on to promote Parker’s story in print, in the March 1862 issue of his newsletter, a few weeks after having made the lecture circuit in New York and Boston. Parker’s arrival in New York was fortuitous for Douglass and other abolitionists, and who pointed to Parker’s account as evidence of claims they had been making for months. Parker’s claims of vast numbers of black troops in Confederate ranks isn’t corroborated by contemporary sources, but whether they reflected a misunderstanding on his part, or an intentional exaggeration for an appreciative northern audience, matters little. The widespread belief in their existence in the first months of 1862 helped drive the national narrative that began with the appearance of the first “contrabands” at Fortress Monroe in 1861, the First Confiscation Act in August of that same year, and through the preliminary announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, that opened the door to enlistment of African American men in the Union army the following year. By August of 1863, Douglass would be making his case for equal pay for black soldiers to Secretary of War Stanton and to President Lincoln in person, within the walls of the White House itself.

Many thanks to Dan Weinfeld, who did the hard work of tracking down the source material for this post.

__________

[1] Boston Evening Transcript, February 6, 1862, 1.

[2] Douglass Monthly, March 1862, 623.

[3] Kate Masur, “Slavery and Freedom at Bull Run,” New York Times Disunion blog, July 27, 2011.

[4] Rochester, New York Union & Advertiser, February 12, 1862, 1.

[5] Newark Daily Advertiser, February 19, 1862, 2.

[6] New York Evening Post, January 24, 1862, 2.

[7] Douglass Monthly, March 1862, 625; New York Evening Post, January 24, 1862, 2.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Glenn David Brasher, The Peninsula Campaign and the Necessity of Emancipation: African Americans and the Fight for Freedom (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2012), 78.; New York Times, January 16, 1862; Brasher, 78.

Louis Napoleon Nelson in The Confederate Veteran

A colleague doing genealogical research passed along this item regarding Louis Napoleon Nelson from the March 1932 issue of The Confederate Veteran magazine (p. 110). As was the case with his pension record, this is an item that seems to be consistently overlooked or ignored on the numerous websites — 3,000-plus hits on the Google machine — that discuss his activities in 1861-65. Which is odd, considering that the source, Confederate Veteran, was (and is) the official publication of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, a group that has gone to great lengths in recent years to promote Nelson’s story, or at least a particular version of it.

On the 6th of February, after an illness of several weeks, Gen. E. R. Oldham, Commander of the 3rd Brigade, Tennessee Division, U.C.V., died at his home in Henning, at the age of eighty-seven years. Burial was at Maplewood Cemetery in Ripley, with Confederate veterans of the county as pallbearers.

At the grave, four comrades, one of them being GEN. C. A. DeSaussure, Commander in Chief, U.C.V., in Confederate uniforms, held the four corners of the Confederate flag, forming a canopy over the casket as it was lowered.

At the close of the funeral services, Lewis Nelson, an old negro of ante-bellum days, who served his master throughout the war, gave in his own words his estimates of “Mars Ed.”

As the funeral cortege left the home, the old plantation bell, which had been rung for over a hundred years, decorated with a Confederate flag, was tolled eighty-seven times.

So consider this another addition to the public record.

____________

A Little Knowledge. . . .

Over at Mid-South Flaggers, the admin there has been doing a little independent research on Confederate pensions from Washington County, Mississippi, and is disturbed by what he’s found — or rather, what he’s not found:

![]()

He’s right; the word “slave” does not appear on the documents he’s looking at. Instead, they’re referred to as “servants,” and there are thirteen of them listed on the page he posted to illustrate his findings:

![]()

![]()

True, an example servant’s pension application he posted requires applicants to identify “the name of the party whom you served,” and the military unit “in which your owner served,” but it doesn’t use the word slave, and that’s what matters, right?

Yes, Mid-South Flagger, you’ve been lied to. Just not by who you think.

______________

The (Very) Posthumous Enlistment of “Private” Clark Lee

Kevin and Brooks have been all over the Georgia Civil War Commission, and particularly of its handling of the case of Clark Lee, “Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier.” I won’t rehash all of that, but there are a few points to add.

Kevin and Brooks have been all over the Georgia Civil War Commission, and particularly of its handling of the case of Clark Lee, “Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier.” I won’t rehash all of that, but there are a few points to add.

First, kudos to Eric Jacobson, who noticed that the modern painting of Lee used by the commission on its marker (right) is almost laughably tailored to affirm Lee’s status as a soldier, including the military coat with trim and brass buttons, rifle, cartridge box belt, military-issue “CS” belt buckle, and revolver, all backed by a Confederate Battle Flag — even though the Army of the Tennessee didn’t adopt that flag until the appointment of General Joseph E. Johnston, well after the Battle of Chickamauga.

It’s probably also worth noting that the man in the painting looks a lot older than 15, the age the Georgia Civil War Commission says Lee was at the time of the battle.

As it turns out, several weeks ago the SCV and other heritage folks installed and dedicated a new headstone for Lee, explicitly (and posthumously) giving him the military rank of Private. The stone also states that Lee “fought at” Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain, the Atlanta Campaign, and a host of other engagements by the Army of Tennessee. These are very specific claims, so it’s worth asking what the specific evidence for them is.

![]()

E. Raymond Evans (center, with umbrella), author of The Life and Times of Clark Lee: Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier, speaking at an SCV memorial service for Clark Lee in April 2013. From here.

![]()

As is so often the case, there doesn’t appear to be any contemporary (1861-65) record of Lee’s service. There is no compiled service record (CSR) for him at the National Archives. Presumably the historical marker, the headstone, and a recent privately-published work on Clark Lee are all based on his 1921 application for a pension from the State of Tennessee, where he had moved in the years after the war. You can read Lee’s complete pension application here (29MB PDF). I cannot find a word in it that mentions or describes Clark Lee’s service under arms, or in combat. There is a general description of Lee’s wartime activities, but it’s quite different from what the Georgia Civil War Commission wants the rest of us to understand about him. I’ve put it below the jump because of some of the unpleasant themes expressed.

Norris White, Black Confederate “Brothers” and the “Flipside” to Glory

A while back, Kevin highlighted a news item on Norris White, Jr., a graduate student at Stephen F. Austin State University who was making the rounds last year, doing presentations and generally talking up the subject of African American soldiers in the Confederate army. Norris White seems to be serious and well-intentioned, and (thankfully) he’s no stream-of-consciousness performance artist like Edgerton. But being sincere is not the same thing as being right. For all his insistence that he’s using primary sources, White’s interviews seem to be little more than reiterating black Confederate rhetoric that the SCV has been asserting for years. While he insists on the importance of primary source materials — “100 percent irrefutable evidence — letters, diaries, pension applications, photographs, newspaper accounts, county commission records and other evidence” — there’s little indication that he’s looked carefully at the materials, or understands them in the larger context of the war and the decades that followed. It’s very shallow stuff he’s doing, hand-waving at a pile of reunion photographs, pension records and loose anecdotes and saying, “see? Black Confederates!” Anyone can do that, and plenty of people do.

It says a lot about the depth of his research that in interviews, White has repeatedly singled out two Texas Historical Commission markers as evidence of his much larger claims about “Black Texans who served in the Confederate Army.” These markers, one to Randolph Vesey (Wise County) and the the other to Primus Kelly (Grimes County), are worth closer examination for what they say, and what they don’t. I obtained copies of the historical marker files for both markers, that you can dowload here (Vesey) and here (Kelly). Both men, as was usual at the time the markers were set up, were explicitly and effusively lauded for their loyalty and sacrifice not to the Confederacy but as (in the case of Kelly), “a faithful Negro slave,” right there in the very first line of the marker.

The files are thin — the THC was less diligent about documentation in past decades than they are now — but neither file contains any contemporary documentation of its subject at all. Both amount to a recording of local oral tradition, which is vivid not though always reliable. Both accounts make it explicitly clear that the two men went to war as personal servants, Vesey to General William Lewis Cabell, and Kelly to the West brothers, troopers in the Eighth Texas Cavalry. But it’s very thin stuff to spin into a claim that “the number of black Texans who participated in the Confederate Army in the War Between the States may have been as high as 50,000,” which would be a figure substantially higher than the entire male slave population of Texas between ages 15 and 50 in 1860, which was a bit under 44,000. Claims like that on White’s part seriously undermine his credibility.

Vesey’s and Kelly’s stories, as reflected in the marker files, are well worth reading, and telling. In Vesey’s case, his wartime experiences with General Cabell probably paled in comparison with his being captured by Indians a few years later and being held prisoner for three months, until his release was secured by one of the legendary characters of the Texas frontier during that time, Britt Johnson.

Primus Kelly’s marker file, though, is much more interesting from the perspective of the advocacy for black Confederates, because included in the file is a 1990 article by Jeff Carroll on Vesey from Confederate Veteran magazine, the official publication of the SCV. The magazine article is a reprint of an article that first appeared in the Midlothian, Texas Mirror on May 31, 1990. Kevin has often suggested that the Confederate Heritage™ groups’ push to find black Confederates in the 1990s was, in part, a reaction to the success of the film Glory (1989), and its depiction of both African American Union soldiers. In light of that, it’s significant that Carroll’s article was originally published just six weeks after Denzel Washington won an Oscar for his role as Private Trip in that film, and moreover, was explicitly framed by its author as the “flipside” to that work:

![]()

There’s no indication that Carroll referenced any materials on Kelly other than the text of the marker itself, but he embellishes that text with all sorts of assertions that are completely unsupported. Take, for example, this passage from the marker:

![]()

![]()

In Carroll’s retelling, this becomes:

![]()

![]()

There’s a world of difference between “West sent Kelly” and “Primus refused to stay at home,” but it’s entirely typical of the way advocates like Carroll depict African American men’s involvement with the Confederate army; it’s always shown as voluntary choice, motivated by noble intent, never out of legal obligation or against their wishes.

The is no evidence in the historical marker files of Kelly’s relationship with the West sons, much less the suggestion that they were “constant companions.” Carroll begins his essay by making the generalized claim that “custom often dictated that the sons of a slave owner received as their own property and slaves of their own age when they’ were children. They were daily and inseparable companions who shared the experience of growing up and became surrogate brothers,” and then paints that assertion right across Primus Kelly. He characterizes Kelly’s relationship with the Wests as that of “brothers” three more times in five short paragraphs, based (as far as I can tell) on no evidence whatsoever. We’ve seen claims like these made falsely before.

![]()

![]()

It’s also highly unlikely that Primus Kelly would have been an “inseparable companion” to any of the West brothers, given the difference in their ages. According to the 1870 U.S. Census (above), Primus Kelly was born about 1847, making him much younger than Robert (age 22 upon enlistment in 1861, giving him a birthdate of c. 1839), John (age 27 upon enlistment in 1861, birthdate c. 1834), or Richard (age 32 upon discharge in January 1863, birthdate c. 1831). Primus Kelly was about eight years younger than the youngest of the Wests, and in fact was barely into his teens when he accompanied the Wests off to war. He was not a childhood companion of any of these men, and the three brothers were living at Lynchburg in Harris County — almost 100 miles away from their father in Grimes County — at the time of the 1860 census.

Carroll’s description of the Wests is somewhat misleading, as well. According to the marker, Richard was reportedly wounded twice in battle and escorted all the way back to Texas by Kelly. Carroll repeats this claim, without question. But if this happened, neither wound is recorded in his compiled service record at NARA. What is recorded is that Richard was given a medical discharge for chronic illness not related to combat injuries in January 1863, nine months after enlisting. It seems very unlikely that during those nine months, Richard West would have been twice wounded so severely that he required an extended convalescence back home in Texas, and made the round journey twice, without there being a record of it in his file.

The three brothers did not enlist together, as Carroll suggests; Robert and John, ages 22 and 27 respectively, enlisted in September 1861, when the regiment was first being organized, while their older brother Richard, age 31 or 32, didn’t join the regiment until May of 1862. Carroll cites Chickamauga (September 1863) and Knoxville (November/December 1863) as fights in which Terry’s Rangers participated, but only Robert might have been present, as he was taken prisoner sometime during the latter part of 1863. Richard was medically discharged, and John was dead. Robert died in April 1905, his obituary appearing in the Confederate Veteran magazine in July of that year.

Kelly is said to have followed the Wests into action, “firing his own musket and cap and ball pistol.” There are many such anecdotes from the war, and they may well be true in Kelly’s case. There is a report in the OR (Series I, Vol. XVI, Part 1, p. 805) by a Union officer from the Battle of Murfreesboro, July 1862, that “The forces attacking my camp were the First [sic., Eighth] Regiment Texas Rangers, Colonel Wharton, and a battalion of the First Georgia Rangers. . . . There were also quite a number of negroes [sic.] attached to the Texas and Georgia troops, who were armed and equipped, and took part in the several engagements with my forces during the day.” But if this is one of the events that Kelly participated in, it underscores the argument that those men were camp servants following their troopers into action, rather than troopers in their own right.

Did Carroll set out to fictionalize Primus Kelly’s story? I don’t know, but to all intents and purposes that was the result. The end product is as much happy fantasy as fact. And even then, it wouldn’t matter so much were it not that other authors have gone on to cite Carroll, including Kelly Barrow’s Black Confederate. In fact, the article is a mess, in which even knowable, factual information is misrepresented. Under the circumstances, I actually think there is one other thing that this article could appropriately borrow from Glory, and it comes right at the very, very end of the movie:

![]()

This story is based upon actual events and persons.

However, some of the characters and incidents portrayed

and the names herein are fictitious, and any similarity

to the name, character, history of any person,

living or dead, or any actual event is entirely

coincidental and unintentional.

![]()

![]()

Like so much else that’s been written about black Confederates in the last 23 years, Jeff Carroll’s article takes a kernel of fact, churns it in a bucket with inaccurate or flat-out-false information and untethered speculation, to create a warm-and-fuzzy story that reassures the Confederate Heritage™ crowd that it was all good, and there’s nothing particularly troubling or complex about any of it — because, you know, they were like brothers. The thing that’s notable about it is that (1) it’s undoubtedly one of the earliest of its type, (2) it’s offered explicitly as a corrective to the narrative presented in Glory, and (3) it so fully expresses the modern talking points that define the push to relabel men who used to be called (as in Kelly’s case) “a faithful Negro slave,” into something far more palatable for modern audiences.

I understand why people want to believe this happy nonsense; it takes a raw, ugly edge off a time and place they have chosen to embrace tightly. What I don’t understand is how someone like Norris White would fall for it. Unlike most of the folks who peddle this stuff, White presumably has the academic background and the research skills to dig into the weeds of this stuff, and understand what the sources actually say. (A good place to start is acknowledging that an historical marker by the side of the highway is not a primary source.) He has the skills and resources to say something new, but instead repeats the same half-truths that have been circulating for decades.

Please, Mr. White, tell Randolph Vesey’s story, and Primus Kelly’s. But tell them fully and completely. Any damn fool can read off the text of a roadside marker and pretend that’s research. You’re better than that, Mr. White, so show us.

____________

Update:

Pension Records for Louis Napoleon Nelson

One of the best-known “black Confederate soldiers” is Louis Napoleon Nelson (right, c. 1846 – 1934), due in large part to the advocacy of his grandson, Nelson Winbush. There are any number of claims made for the nature of Nelson’s service, such as these:

One of the best-known “black Confederate soldiers” is Louis Napoleon Nelson (right, c. 1846 – 1934), due in large part to the advocacy of his grandson, Nelson Winbush. There are any number of claims made for the nature of Nelson’s service, such as these:

[Winbush’s] grandfather, Louis Napolean Nelson, was a private in Co. M, 7th Tennessee Cavalry of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. Private Nelson was a slave at the start of the war. He began his military service as a cook, then a rifleman, and finally a chaplain.

Virtually nothing, however, has been offered in the way of documentation of such claims. So in the interest of injecting something tangible into future discussions of Nelson’s activities during the war, here is his 1921 Tennessee Confederate pension file (PDF).

___________

How — and Why — Real Confederates Endorsed Slave Pensions

In another forum recently, there was a lively discussion going on about the historical basis for present-day claims about black Confederates. One of the topics, naturally, was the pensions that some states awarded to African American men who had served as body servants, cooks, and in other roles as personal attendants to white soldiers. One person asked why it was that the former states of the Confederacy were so late in authorizing pensions for these men, or (in some cases) did not authorize them at all. It’s a good question, that I’m sure defies a single, simple answer.

But in the process of looking for something else, I came across this editorial in the October 1913 issue of the Confederate Veteran, calling on the states to provide pensions for a “a particular class of old slaves.” I’m putting it after the jump, because it’s peppered with racial slurs and stereotypes that are hurtful to modern ears, but were wholly unremarkable for that time, place and publication. So let me apologize in advance for the language, and hope that my readers will appreciate the necessity of repeating it here, in full and in proper context, in order to be crystal clear about the author’s meaning and intent. There are times when polite paraphrasing just doesn’t do the job.

As you read this editorial, keep in mind that the Confederate Veteran, by its own masthead, officially represented (1) the United Confederate Veterans, (2) the United Daughters of the Confederacy, (3) the Sons of Veterans (i.e., the SCV), and other groups. The magazine was mostly written by Confederate veterans and their families, to be read by Confederate veterans and their families. While the editorial may not reflect formal UCV/UDC/SCV policy, its appearance in the magazine does indicate that its perspective is one that would be shared by the magazine’s readership, and its call for action would reach a willing and receptive audience.

In short, if you want to know how real Confederate veterans viewed the purpose and necessity of pensions for former slaves, start here:

![]()

What Does Hannibal Alexander Tell Us About Black Confederate PoWs?

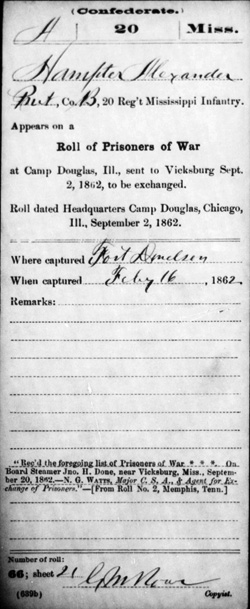

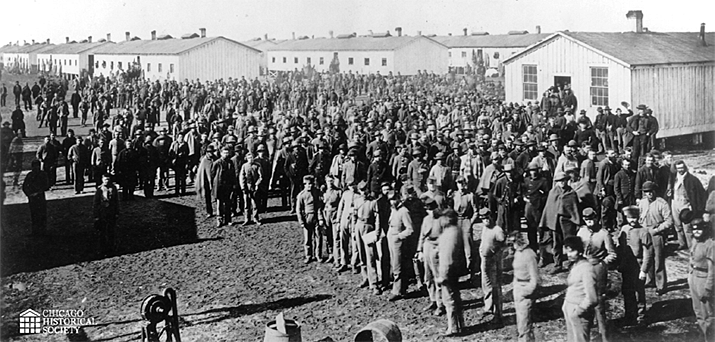

One of the things that’s often offered as evidence of African Americans serving as Confederate soldiers is the fact that some of these men were captured and held in Northern prison camps. Why would these men be held if they were not soldiers? goes the thinking, and there are PoW records that show them as soldiers. It’s a compelling rhetorical argument, but reality is oftentimes more complex than that. From the Confederate Veteran, January 1901:

Hannibal Alexander was a slave belonging to Parker Alexander. He went with his young master, Sidney Alexander, to the war, and did his duty faithfully. “Ham” died recently in Monroe County, Miss. He and his wife Delia by industry made a good living and accumulated a competence, ever having the confidence and friendship of the white people about their lifetime home. Writes W. A. Campbell, of Columbus :

In the army he was cook. He was in the siege of Fort Donelson. He was captured there, and went to Camp Douglass [sic.] as a Confederate prisoner. He answered roll call all the time as a white soldier. Being a bright [i.e., light-skinned] mulatto, he was brought to Vicksburg and exchanged with the others, and again went with his young master into service.

The Federal sergeant that called the roll was somewhat suspicious as to “Ham” (as he was called by the boys) being a slave, but he was told that living in Mississippi he was sunburned and that made him dark.

Hannibal was a very intelligent negro [sic.], and knew if he left his master he could go free, but he elected to stay with him among the white men he had been raised with, and preferred to suffer with them.

I knew Hannibal for more than forty years as slave and freeman, and he was ever polite and friendly to all his former owners. In the old days I went on many a hunting and fishing expedition with Sidney, with “Ham” to wait on us.

His old master with whom he went in the army is yet alive, but in poor health.

There are a number of examples of mixed-race men “passing” to enter Confederate military service, only to be discharged when found out; Alexander’s is a case of “passing” to remain with his master inside the confines of Camp Douglas.

There are a number of examples of mixed-race men “passing” to enter Confederate military service, only to be discharged when found out; Alexander’s is a case of “passing” to remain with his master inside the confines of Camp Douglas.

There’s a lot to digest in Hannibal Alexander’s story. The Confederate Veteran story is framed, typically, as that of a slave’s lifelong fidelity to his master, and willingness to suffer the (very real) hardships of a Federal prison camp to do so. (This short piece is part of a section called, “Faithful Negroes Who Were Slaves.”) But it’s important to recognize that this story makes it clear that in remaining in the camp, Alexander consciously chose to represent himself as a white soldier, rather than his actual status as an enslaved cook. The article also argues that his decision to remain was one of personal loyalty to his master, not to the regiment or the Confederacy. As others have often pointed out, it’s not sufficient just to say a man “served” when talking about slaves and the Confederate army; it’s important to make a distinction about who or what he was in service to.

And of course, we have nothing at all from Alexander himself to explain his decision.

Alexander’s story is revealing because a number of “black Confederate solders” have been so identified on the basis of documents just like Alexander’s compiled service record (CSR, right) that record their presence in Union prison camps. Based on his assumed identity, Alexander’s card identifies him as a private in the 20th Mississippi Infantry, a rank he never actually held. Significantly, too, there are only two items in Alexander’s CSR folder, both relating to his parole, and originating from Camp Douglas (“roll dated Headquarters Camp Douglas, Chicago, Ill.”). There’s no Confederate record for him, dating from before or after Camp Douglas, because he wasn’t considered a soldier. By comparison, the CSR for the master he served, Sidney Alexander, contains nine separate cards detailing his career as a private in Co. B of that regiment.

Hannibal Alexander’s case is an intriguing one for a number of reasons. How valuable would it be to have Alexander’s own, unvarnished account of these events, rather than as told through the eyes of his former master’s old friend? It would be useful to know how many African American cooks and servants found themselves, like Hannibal Alexander, swept up by the Union army and made the decision to remain in the camp, passing themselves off as enlisted soldiers to do so. It’s also a good object lesson in how there might be a CSR in the National Archives for a man who was never actually recognized as a soldier by the Confederacy.

Oh, one other thing — the Confederate Veteran piece says that Sidney Alexander returned to military service, but his CSR notes that in March 1863, six months after his parole from Camp Douglas, Sidney received a discharge after hiring a substitute. Rich man’s war, poor man’s fight, y’all.

___________

Image: Camp Douglas, Chicago, c. 1863. Chicago Historical Society.

Soldiers All

Recently I’ve gotten the sense that, among those who are pushing broad, generalized assertions about the involvement of African Americans in the Confederate war effort, there’s been a notable tendency to back off the specific claim that they were recognized as soldiers at the time, opting instead for much more vague terms like “black Southern loyalist” that, having no clear objective standard to begin with, can also neither be directly refuted. Such language is warm and fuzzy, but has the great advantage that it can be applied to almost anyone, based on almost anything. It also tells us as much about the speaker as it does about the subject.

Nonetheless, one of the more prominent advocates on the subject of BCS continues to twist herself in rhetorical knots to demonstrate retroactively that African American cooks, body servants, teamsters and so forth should actually be considered Confederate soldiers, regardless of how they were viewed at the time. She recently proposed definitions of “Black Confederate” and “Black Confederate Soldier:”

A “Black Confederate” is an African-American who is acknowledged as serving with the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

A “Black Confederate Soldier” is (1) an enlisted African-American in the Confederate States Army, (2) an African-American acknowledged by Confederate Officer(s) as engaged in military service, and/or (3) an African-American approved by the Confederate Board of Pension Examiners to receive a Confederate Pension for military service during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

There are multiple problems with these definitions. The first is that there’s no practical difference between “acknowledged as serving with the Confederate States Army” (Definition 1) and “acknowledged by Confederate Officer(s) as engaged in military service” (Definition 2). A Venn diagram of these would be an almost perfect circle. In this suggested scheme, “Black Confederate” and “Black Confederate Soldier” are entirely equivalent. Anyone should be able to see that, even without knowing anything more about the subject.

Second, she defines a soldier as anyone acknowledged “as having engaged in military service,” which falls back on the never-defined, all-encompassing word “service.” This is a common technique — see the discussion thread here — which sounds simple enough, but conflates a whole range of activities that, at the time, fell into clearly-defined realms.

Third, she’s still hopelessly muddled on the subject of pensions — who awarded them, and what they were awarded for, and what classes of pensions were awarded. Some states awarded pensions explicitly for former slaves/servants (e.g., Mississippi), while others did not. There was no single, central body called the “Confederate Board of Pension Examiners;” pension programs were set up by individual states, each with their own rules and procedures. Individual applications were usually reviewed and endorsed by local boards, which introduces all sorts of unknown variables in procedure and documentation. In at least some cases, the state verified applicants’ service records with the War Department — these materials were later transferred to the National Archives — and even this verification process appears to have resulted in at least one error of mis-identification. The famous Holt Collier, who probably comes as close as anyone to having actually been a Confederate combatant in practice, received three pension awards from Mississippi in his old age — first as a personal body servant, then as a soldier, then again as a servant. In short, pension records tell us very little about the applicants’ status forty, fifty, sixty years before. (The basic primer to understanding the process for awarding Confederate pensions — and their limitations — remains James G. Hollandsworth, Jr.’s manuscript, “Looking for Bob: Black Confederate Pensioners After the Civil War,” in the Journal of Mississippi History.)

This particular researcher has a long track record of glossing over distinctions between slaves and free African Americans, personal servants, cooks, and enlisted soldiers under arms. In the interest of reconciliation and reunion, she consistently rejects the hard realities of race, law and society in the mid-19th century, and insists that all Confederates, writ broad, saw themselves as standing on an equal footing. In an effort to draw an equivalency between African American men employed as cook in the Confederate army with those in the Union, she latches onto a single, three-word notation in the record of one Private Lott Allen of the 21st USCT :

On the left, Lot Allen enlisted with the Union Army 21st United States Colored Troops (USCT) Company A as an “on order cook.” [sic., “in duty cook”] On the right, William Dove enlisted with the Confederate States Army North Carolina 5th Cavalry Company D as a “cook.” Both men contribute to United States Military history; and their soldier service records are each recorded in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

Her statement about Private Allen is factually incorrect; as his compiled service record from NARA (14MB PDF) makes clear, Lott Allen enlisted as a U.S. soldier and, being 42 years old, was immediately assigned to work as a cook because he couldn’t keep up as an infantryman. His disability discharge from June 1865 says so explicitly: “Since his enlistment to the present date he has been Company Cook and is too old a man to perform the duty of a soldier.” The regimental surgeon, John M. Hawks, goes on to explain that Allen is unable to perform the duties of a soldier because of “old age; its consequent disability and infirmities. He has never been able to drill, or to march with the company, or do any military or fatigue duty; and he is too careless and slovenly for a cook.” Private Lott Allen didn’t enlist as a cook; he enlisted as a soldier, couldn’t cut it, and (it seems) wasn’t very good as a cook, either.

Posting elsewhere, the researcher takes her assumption about Private Allen and spins it off into a grand, sweeping claim encompassing thousands or tens of thousands of others:

The question is: Were there cooks, teamsters, laborers in the Union Army United States Colored Troops? The answer is yes. As an example in the image of this post, Private Allen Lot [sic.], a soldier with the Union Army 21st United States Colored Troops, served as an “On [sic.] Duty Cook.” See Private Allen Lot’s Union Soldier Service Record (NARA Catalog ID 300398).

Therefore, with this preponderance of the evidence, African-Americans on Confederate Soldier Service Records (muster rolls) who are listed as cooks, teamsters, laborers, etc. should likewise be called soldiers. The sun rises and it shines on us all.

She takes a single notation that this man was assigned as a cook and then extrapolates that to argue that all “who are listed as cooks, teamsters, laborers, etc. should likewise be called soldiers.” She makes what is formally known as a “converse accident,” but is a simple and obvious logical fallacy: she reasons that this soldier was a cook; therefore all cooks were soldiers. (And teamsters, and laborers. . . .)

It’s hard to know whether this researcher bothered to look at all of Allen’s CSR or just didn’t understand it, but it really doesn’t matter. Either way she misrepresents Allen’s actual situation, and then uses that flawed example to make a sweeping rhetorical argument applied to tens of thousands of men in an entirely different army.

This is, sadly, typical of most of the “research” that goes into BCS advocacy; it’s a mile wide and a half-inch deep. It’s pulling out a word here, a line there, and announcing it as “proof” with little consideration of the full record, even when, as in this case, it’s readily available. It’s about adding names to a list, with little or no real understanding of the larger story, or the historical context of the claim being made. It’s just unbelievably superficial.

There’s no question that tens of thousands of African Americans went into the field with the Confederate army as cooks, personal servants, teamsters, laborers, and so on. Some were free; most were slaves. Some undoubtedly went willingly, but far more went with with some degree of coercion (legal, economic, physical) guiding their steps. Some saw combat, even though very, very few were officially in a combat role. There is a tremendous, untapped resource there for serious research. But they were not formally considered soldiers at the time, by either the Confederate or Union army. Robert E. Lee didn’t recognize these men as soldiers; he thought such pretensions made a fine joke. Howell Cobb didn’t recognize these men as soldiers. Kirby Smith didn’t see these men as soldiers. So why do some people today, like this researcher, devote so much effort to retroactively designate them so? Why is “proving” that point so much more important than telling their actual stories as individuals? Sure, this researcher finds Lott Allen and William Dove useful for making an analogy, but does she offer any additional information about them? (Hint: if you’ve read this far, you already know more about Lott Allen than you’re ever likely to find on the researcher’s site.)

I regret feeling obligated to make this post at all, and have no doubt it will be framed as a personal attack on this particular researcher’s character. It’s not; I’ve repeatedly said before, and still believe, that she is sincere and well-intentioned in her efforts. But it’s also clear that she doesn’t understand the materials she’s working with, and has no sense of her own limitations in that regard. But she is viewed as a among BCS advocates as a leading researcher on the subject, and maintains an extensive website dedicated to it. If she is to be respected and valued as a researcher, she needs to be subject to the same fact-checking on her research and methodology that the rest of us are; she doesn’t get a pass because she’s not professionally trained, or because she’s well-intentioned.

There’s a saying, much quoted by True Southrons™, that “history is written by the winners.” This reflects their sincere belief that their own preferred historical narrative is somehow suppressed by professional historians and censored in academic curricula. That’s wrong; history is history, regardless of who writes it. But the work they do needs to stand up to scrutiny, and most of it just doesn’t.

_______________

17 comments