What Does Hannibal Alexander Tell Us About Black Confederate PoWs?

One of the things that’s often offered as evidence of African Americans serving as Confederate soldiers is the fact that some of these men were captured and held in Northern prison camps. Why would these men be held if they were not soldiers? goes the thinking, and there are PoW records that show them as soldiers. It’s a compelling rhetorical argument, but reality is oftentimes more complex than that. From the Confederate Veteran, January 1901:

Hannibal Alexander was a slave belonging to Parker Alexander. He went with his young master, Sidney Alexander, to the war, and did his duty faithfully. “Ham” died recently in Monroe County, Miss. He and his wife Delia by industry made a good living and accumulated a competence, ever having the confidence and friendship of the white people about their lifetime home. Writes W. A. Campbell, of Columbus :

In the army he was cook. He was in the siege of Fort Donelson. He was captured there, and went to Camp Douglass [sic.] as a Confederate prisoner. He answered roll call all the time as a white soldier. Being a bright [i.e., light-skinned] mulatto, he was brought to Vicksburg and exchanged with the others, and again went with his young master into service.

The Federal sergeant that called the roll was somewhat suspicious as to “Ham” (as he was called by the boys) being a slave, but he was told that living in Mississippi he was sunburned and that made him dark.

Hannibal was a very intelligent negro [sic.], and knew if he left his master he could go free, but he elected to stay with him among the white men he had been raised with, and preferred to suffer with them.

I knew Hannibal for more than forty years as slave and freeman, and he was ever polite and friendly to all his former owners. In the old days I went on many a hunting and fishing expedition with Sidney, with “Ham” to wait on us.

His old master with whom he went in the army is yet alive, but in poor health.

There are a number of examples of mixed-race men “passing” to enter Confederate military service, only to be discharged when found out; Alexander’s is a case of “passing” to remain with his master inside the confines of Camp Douglas.

There are a number of examples of mixed-race men “passing” to enter Confederate military service, only to be discharged when found out; Alexander’s is a case of “passing” to remain with his master inside the confines of Camp Douglas.

There’s a lot to digest in Hannibal Alexander’s story. The Confederate Veteran story is framed, typically, as that of a slave’s lifelong fidelity to his master, and willingness to suffer the (very real) hardships of a Federal prison camp to do so. (This short piece is part of a section called, “Faithful Negroes Who Were Slaves.”) But it’s important to recognize that this story makes it clear that in remaining in the camp, Alexander consciously chose to represent himself as a white soldier, rather than his actual status as an enslaved cook. The article also argues that his decision to remain was one of personal loyalty to his master, not to the regiment or the Confederacy. As others have often pointed out, it’s not sufficient just to say a man “served” when talking about slaves and the Confederate army; it’s important to make a distinction about who or what he was in service to.

And of course, we have nothing at all from Alexander himself to explain his decision.

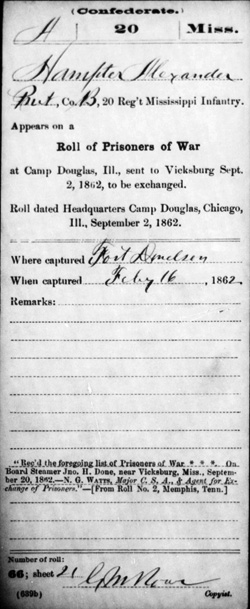

Alexander’s story is revealing because a number of “black Confederate solders” have been so identified on the basis of documents just like Alexander’s compiled service record (CSR, right) that record their presence in Union prison camps. Based on his assumed identity, Alexander’s card identifies him as a private in the 20th Mississippi Infantry, a rank he never actually held. Significantly, too, there are only two items in Alexander’s CSR folder, both relating to his parole, and originating from Camp Douglas (“roll dated Headquarters Camp Douglas, Chicago, Ill.”). There’s no Confederate record for him, dating from before or after Camp Douglas, because he wasn’t considered a soldier. By comparison, the CSR for the master he served, Sidney Alexander, contains nine separate cards detailing his career as a private in Co. B of that regiment.

Hannibal Alexander’s case is an intriguing one for a number of reasons. How valuable would it be to have Alexander’s own, unvarnished account of these events, rather than as told through the eyes of his former master’s old friend? It would be useful to know how many African American cooks and servants found themselves, like Hannibal Alexander, swept up by the Union army and made the decision to remain in the camp, passing themselves off as enlisted soldiers to do so. It’s also a good object lesson in how there might be a CSR in the National Archives for a man who was never actually recognized as a soldier by the Confederacy.

Oh, one other thing — the Confederate Veteran piece says that Sidney Alexander returned to military service, but his CSR notes that in March 1863, six months after his parole from Camp Douglas, Sidney received a discharge after hiring a substitute. Rich man’s war, poor man’s fight, y’all.

___________

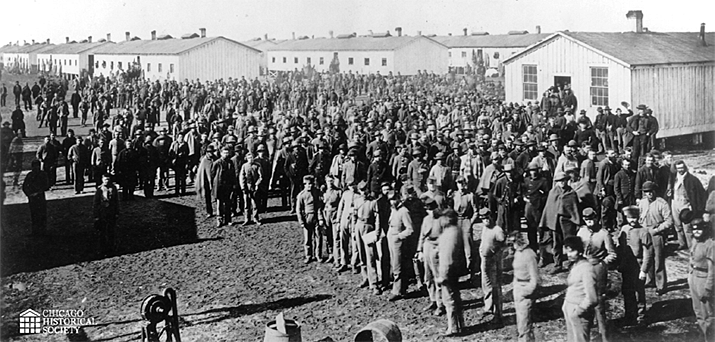

Image: Camp Douglas, Chicago, c. 1863. Chicago Historical Society.

30 comments