See Y’all at the Houston History Book Fair, November 10

I’ll be speaking on my new book, The Galveston-Houston Packet: Steamboats on Buffalo Bayou, at the Houston History Book Fair and Symposium on November 10. It’s free and open to the public, so y’all have no excuse not to go. There will be some great presentations there by folks like my friends Ed Cotham, author of Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston and Sabine Pass: The Confederacy’s Thermopylae, and Jim Schmidt, author of the just-published Galveston and the Civil War: An Island City in the Maelstrom. It’s been a tremendous privilege to know these two men, and an honor to be included with them in this event.

The Galveston-Houston Packet is not a Civil War book per se, but the central (and longest) chapter in it deals with the Texas Marine Department, a unique organization within the Confederacy that used chartered civilian river steamers to create a logistical support and makeshift naval force, run by civilians, but all under the command of the Confederate army. It was a strange arrangement but, as at the Battle of Galveston on New Years Day 1863, it worked better than anyone should have expected it to.

More generally, the book tells the story of one of the vital early transportation routes that shaped the development of Texas. Most people imagine the settlement of the American West as signaled by the dust of the wagon train, or the whistle of a locomotive, but during the middle decades of the 19th century, though, the growth of Texas and points west centered around the 70-mile water route between Galveston and Houston. This single, vital link stood between the agricultural riches of the interior and the mercantile enterprises of the coast, with a round of operations that was as sophisticated and efficient as that of any large transport network today. At the same time, the packets on the overnight Houston-Galveston run earned a reputation as colorful as their Mississippi counterparts, complete with impromptu steamboat races, makeshift naval gunboats during the Civil War, professional gamblers and horrific accidents. The 143-page book includes endnotes, bibliography, rare photos, two original maps, and an index. It’s now available for pre-order at Amazon or Barnes & Noble at a great pre-publication price!

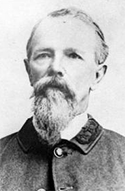

A few of the images included:

Stonewall Jackson Killed by His Own Troops (Again)

![]()

It’s been a little over a year since the Lexington, Virginia City Council voted to bar all but the U.S., Virginia and municipal flags from city-owned light poles in the town. The decision was met with protests then, but there have been relatively few developments since. There was a lawsuit, of course, that was tossed out by the judge in June, and if there have been any other major developments on the legal side of the dispute, I’m not aware of them.

So to keep stirring the pot, now local SCV Camp Commander Brandon Dorsey points to the closure and layoffs as a local tourist attraction the Theater at Lime Kiln. This, Dorsey, claims, is “thanks to Lexington City Council,” and somehow vaguely the result of political correctness. Dorsey doesn’t actually explain the connection, though, which is not really surprising, given that the attached news item about the closure makes no such inference. Indeed, the article makes it clear that the theater has been in dire straits financially for the better part of a decade:

![]()

When the theater launched the fund drive earlier this year, Russell said Lime Kiln “has been on life support for the past several seasons.” He said the theater has managed with a staff of three doing the work of 10, but that there were no more expenses that could be cut, while the theater’s facility continued to deteriorate and consume what little cash reserves exist. The theater has asked Lexington and Rockbridge County to make $200,000 in multiyear pledges by Dec. 31, in order to make needed repairs and build a new permanent rain structure. It also is seeking a $93,000 rural development loan from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. When it asked for that help earlier this year, Lime Kiln said it needed a total of $300,000 by the end of the year to do all the work it needed to do in order to present a 10-performance season in 2013. It hopes to grow to 15 performances in 2014 and to become self-supporting. The theater closed for a while in 2005, and now says its signature production, “Stonewall Country,” seriously overstretched its ability to operate, because of its high cost.

My emphasis. For the record, 2005 is SIX YEARS before the Lexington City Council took action on the flag ordinance.

What we have here is, pretty obviously, a case where a long-standing business that’s been teetering on the precipice for years eventually succumbs to hard economic times and competition for visitors’ entertainment dollars. Although the theater’s signature production, “Stonewall Country” (above), focuses on the life of Stonewall Jackson, there’s nothing in the news story that suggests that show, in particular, was struggling due to lack of attendance or a general antipathy toward Confederate subjects.

Dorsey offers no evidence supporting his suggestion that Lexington Mayor Mimi Elrod and her PC minions are the root cause of this event, or why, exactly, they would want the closure of a cultural venue that brings visitors and their dollars to town. And of course the ordinance passed had no bearing on the theater or any other business in Lexington. Dorsey’s claim doesn’t even make sense, frankly. But while we’re busy making unsubstantiated accusations, I’ll toss in one of my own, that at least has some logic to it.

Gary Adams claims that the SCV/Virginia Flagger boycott of Lexington has cost local merchants $633,271 in lost revenue already. Where that number comes from, I have no idea — citing the source of material he posts is not a big priority for him — and I’m dubious that it’s even a real number than can be attributed to the boycott.

But just for the moment, let’s assume this is a real number, and the boycott has cost local visitor-oriented businesses well over half a million dollars. It’s not hard to see that under those circumstances the boycott, cheered on by folks like Dorsey, Billy Bearden and Susan Hathaway, may have played a very direct role the demise of the Theater at Lime Kiln. I remain dubious that the boycott has had much real effect at all, but if it has, as its backers claim, then their fingerprints are all over the pink slips handed out to theater employees last week.

Once again, Stonewall Jackson has been killed by his own troops. Well done, asshats.

______________

Abraham Lincoln, Ron Maxwell Killer

I haven’t seen Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, and probably won’t until it comes around on cable. But it has been interesting to witness the reaction to it in certain quarters, particularly True Southrons™ who’ve got their butternut panties in a wad over the depiction of Confederates as vampires. I’m not really sure why they’re surprised at this, given that it was a major plot element in Seth Grahame-Smith’s best-selling 2010 novel upon which the movie is based. Even H. K. Edgerton is getting in on the act. That seems to be a lot more entertaining than the movie probably is, trains and trestles and pyrotechnics notwithstanding.

I haven’t seen Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, and probably won’t until it comes around on cable. But it has been interesting to witness the reaction to it in certain quarters, particularly True Southrons™ who’ve got their butternut panties in a wad over the depiction of Confederates as vampires. I’m not really sure why they’re surprised at this, given that it was a major plot element in Seth Grahame-Smith’s best-selling 2010 novel upon which the movie is based. Even H. K. Edgerton is getting in on the act. That seems to be a lot more entertaining than the movie probably is, trains and trestles and pyrotechnics notwithstanding.

AL:VH isn’t setting any box office records, to be sure. But what’s interesting is how well it’s done compared to other, more serious CW pieces, notably Gettysburg (1993) and Gods and Generals (2003). In its first three weeks, AL:VH has taken in far more at the box office ($34M) than either of those epics did in their entire theatrical runs, after adjusting for inflation. Indeed, AL:VH looks to be on track to outsell both those films, combined, before it ends its theatrical run in the U.S. It’s three-quarters of the way there already:

AL:VH isn’t any great threat to Americans’ understanding of history, nor is it a harbinger of “cultural genocide” or whatever folks are whinging about. It’s a wild-ass fantasy, and is no more libelous of the Confederacy than Gotham City is of New York. Still, it’s too bad the cash follows movies like this, rather than efforts that at least attempt to tell a real story.

______________

Coming to a Newsstand Near You

The new issue of the Civil War Monitor is now online, and should be appearing on newsstands and in mailboxes in short order. It’s a great issue this time (again — they keep doing that), with a focus on events in the sesquicentennial year of 1862. Feature articles in this issue include:

Lee: Initial Stride to Greatness

In his first campaign as Confederate army commander, Robert E. Lee established his reputation as a bold leader—and changed the course of the war in the East. By Jeffry D. Wert A Capital in Crisis

Twelve summer days in 1862 marked the darkest time of the Civil War for Washington, D.C. By Stephen W. Sears Faces of 1862

The war’s second year forever changed the lives of countless Americans—soldiers and civilians—on both sides of the conflict. By Ronald S. Coddington Fighting for South Mountain

On the eve of Antietam, Union soldiers won a decisive victory—then fought again to have it remembered. By Brian Matthew Jordan

Northern Divide

The elections of 1862 seemed to offer a severe rebuke to Abraham Lincoln and his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The president and his allies, however, read the results much differently. By Louis P. Masur

I particularly like the article by author (and blogger) Ron Coddington, who’s made a sort of scholarship all his own by starting with period CDVs of Civil War soldiers and using those as a jumping-off place for biographical essays that explore the Civil War experience at the micro level. It’s what Barbara Tuchman once described as “history by the ounce,” and it makes for great reading. Toss in some quick book reviews by Brooks Simpson and a fun article on counterfeiting Confederate currency by Ben Tarnoff, and there’s a lot of good stuff in there.

I think I’ve said before that the CWM is not your father’s Civil War magazine. But a subscription would make a nice Father’s Day gift, ya know?

_____________

Focus on U.S.S. Fort Jackson

My friend Ed Cotham e-mailed me recently with this photo of U.S.S. Fort Jackson, one of the ships making up a part of the blockade fleet off Galveston in the final months of the war. Fort Jackson had a long and active service history, capturing several blockade runners off the East Coast and taking part in the bombardment of Fort Fisher at the end of 1864. When she took up station off Galveston in the early part of 1865, she served as the flotilla’s flagship, under Captain Benjamin F. Sands (1811-1883, right). It was Sands who formally took the surrender of Galveston in June 1865.

My friend Ed Cotham e-mailed me recently with this photo of U.S.S. Fort Jackson, one of the ships making up a part of the blockade fleet off Galveston in the final months of the war. Fort Jackson had a long and active service history, capturing several blockade runners off the East Coast and taking part in the bombardment of Fort Fisher at the end of 1864. When she took up station off Galveston in the early part of 1865, she served as the flotilla’s flagship, under Captain Benjamin F. Sands (1811-1883, right). It was Sands who formally took the surrender of Galveston in June 1865.

When I first saw the image, I thought I’d not seen it before, and told Ed so. Soon after I realized that we’d used a much smaller version of this image on the Denbigh Project website, as it was a lookout aboard Fort Jackson that first sighted the stranded blockade runner at dawn on May 23, 1865, and Sands who ordered the gunboats Cornubia and Princess Royal to open fire. Simultaneously, Sands ordered boats from the blockaders Seminole and Kennebec to board and destroy Denbigh.

A very large proportion of both the U.S. and Confederate navies were vessels that were never built for military service, merchant ships that were either bought while still on the stocks, or pressed into service to meet the rapidly-expanding need for warships. Fort Jackson was one of these. She was built for Cornelius Vanderbilt’s service between New York and Panama, but was purchased by the Navy upon completion in the summer of 1863.

Fort Jackson was a big ship, 250 feet long and 1,850 tons burthen. She normally drew 18 feet of water, which would have made operations close inshore in the Gulf of Mexico difficult. (In fact, when Sands went into the harbor at Galveston to formally take possession of the city, he had to transfer to U.S.S. Cornubia, a smaller ship with a 9-foot draft.) Her two sidewheels were powered by a vertical beam engine, consisting of a single cylinder 80 inches in diameter, with a 12-foot stroke. Fort Jackson was armed with a 100-pounder rifle, two 30-pounder rifles, and eight 9-inch smoothbores.

Anyway, looking at the image there seemed to be a lot of good detail, so I downloaded the full-resolution version from the Library of Congress, and thought it would be fun to see what’s visible. Here we go. . . .

“Not a harbour over 8 feet.”

Over at the Big Map Blog, they have an 1862 map showing the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coasts. (The original is in the Library of Congress, here.) The map, published in New York, is intended to show the vulnerability of the Confederate coastline, and the difficulty the South would have in establishing an overseas trade essential to its survival. This was at a time when formal diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy, particularly by France and the United Kingdom, seemed a real possibility, and a potentially-decisive factor in the outcome of the war. The map was, according to its creator, Edmund Blunt,

![]()

prepared to show at a glance the difference in extent of the Coasts of the U. States occupied by the loyal men and rebels; its circulation it is believed will have the effect of counteracting the exertions of Traitors at home as well as abroad.

Blunt continued, “persons having correspondents in Europe would do well to send copies of this sketch to them for Circulation.” Heh.

There are a lot of reasons to appreciate this map as an informative tool, not least of which is that it conveys fairly complex information with extreme economy of line and text. (Edward Tufte‘s great-grandfather probably loved it.) There’s not an unnecessary figure or word on it, Blunt’s propagandizing notwithstanding. Union-occupied parts of the coast are shown with a bold line, while Confederate-held areas are drawn with a lighter line. Each potentially significant port or inlet is marked with the maximum depth of water over the bar at its entrance, a critical factor that restricted the size of ships that might effectively use that port. I like the map because it becomes immediately clear how geography shaped Union naval strategy on the one hand, and Confederate blockade-running on the other — why, for example, Mobile and (later) Galveston became important blockade-running ports in the Gulf of Mexico, while other ports did not.

The map also serves as a reminder of just how sparsely-populated and inaccessible some parts of the South were in the 1860s. Almost the entire coast of Louisiana is written off, “not a Harbour over 8 feet.” The southern tip of Florida (the Everglades) from the Keys westward, is noted as being “swampy or uninhabited.” Almost all of Florida’s Atlantic coast, from St. Augustine south to the Keys, is similarly dismissed as being unimportant militarily, or for maritime purposes. Sorry, Josephine.

So what are your favorite CW maps, and why?

_______________

Why Movies Are More Gooder Than Reality

My favorite scene in the 1993 film Gettysburg is this one, where Hood rides to General Longstreet, his corps commander, to protest the order to make a frontal assault on Little Round Top. It’s brief, direct, and poignant; the way the dialogue is framed, even someone who knows nothing about Gettysburg understands immediately that the attack is doomed to fail. It perfectly encapsulates the conflict between the generals; too bad that encounter never happened.

At least, it didn’t happen the way it’s depicted in the movie, which is widely heralded in some quarters as being particularly faithful to the historical record. There’s no question that Hood protested his orders to make a frontal assault on the Federal position, and reluctantly complied with his orders, but the details of how that exchange came about are considerably different, as reported by three officers who were there.

Here is Evander M. Law’s (1836-1920, right) account of the event, from his article, “‘Round Top’ and the Confederate Right at Gettysburg,” published in the December 1886 issue of The Century Magazine. At the time, Law commanded the Alabama Brigade in Hood’s Division, and succeeded to command of the division when Hood was wounded early in the action:

Here is Evander M. Law’s (1836-1920, right) account of the event, from his article, “‘Round Top’ and the Confederate Right at Gettysburg,” published in the December 1886 issue of The Century Magazine. At the time, Law commanded the Alabama Brigade in Hood’s Division, and succeeded to command of the division when Hood was wounded early in the action:

I found General Hood on the ridge where his line had been formed, communicated to him the information I had obtained, and pointed out the ease with which a movement by the right flank might be made. He coincided fully in my views, but said that his orders were positive to attack in front, as soon as the left of the corps should get into position. I therefore entered a formal protest against a direct attack. . . .

General Hood called up Captain Hamilton, of his staff, and requested me to repeat the protest to him, and the grounds on which it was made. He then directed Captain Hamilton to find General Longstreet as quickly as possible and deliver the protest, and to say to him that he (Hood) indorsed it fully. Hamilton rode off at once, but in about ten minutes returned, accompanied by a staff-officer of General Longstreet, who said to General Hood, in my hearing, ” General Longstreet orders that you begin the attack at once.” Hood turned to me and merely said, ” You hear the order ? ” I at once moved my brigade to the assault. I do not know whether the protest ever reached General Lee. From the brief interval that elapsed between the time it was sent to General Longstreet and the receipt of the order to begin the attack, I am inclined to think it did not. General Longstreet has since said that he repeatedly advised against a front attack and suggested a movement by our right flank. He may have thought, after the rejection of this advice by General Lee, that it was useless to press the matter further.

Just here the battle of Gettysburg was lost to the Confederate arms.

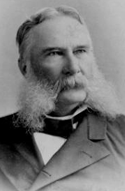

In his own account, James Longstreet (1821-1904) acknowledges Hood’s appeals not to go forward with the attack as planned, but also suggests that even when the matter was decided, Hood dragged his feet in executing it:

In his own account, James Longstreet (1821-1904) acknowledges Hood’s appeals not to go forward with the attack as planned, but also suggests that even when the matter was decided, Hood dragged his feet in executing it:

Hood’s division was in two lines, Law’s and Robertson’s brigades in front, G. T. Anderson’s and Benning’s in the second line. The batteries were with the divisions, four to the division. One of G. T. Anderson’s regiments was put on picket down the Emmitsburg road. General Hood appealed again and again for the move to the right, but, to give more confidence to his attack, he was reminded that the move to the right had been carefully considered by our chief and rejected in favor of his present orders. . . .

Prompt to the order the combat opened, followed by artillery of the other corps, and our artillerists measured up to the better metal of the enemy by vigilant work. Hood’s lines were not yet ready. After a little practice by the artillery, he was properly adjusted and ordered to bear down upon the enemy’s left, but he was not prompt, and the order was repeated before he would strike down.

In his usual gallant style he led his troops through the rocky fastnesses against the strong lines of his earnest adversary, and encountered battle that called for all of his power and skill. The enemy was tenacious of his strong ground ; his skilfully-handled batteries swept through the passes between the rocks ; the more deadly fire of infantry concentrated as our men bore upon the angle of the enemy’s line and stemmed the fiercest onset, until it became necessary to shorten their work by a desperate charge. This pressing struggle and the cross-fire of our batteries broke in the salient angle, but the thickening fire, as the angle was pressed back, hurt Hood’s left and held him in steady fight. His right brigade was drawn towards Round Top by the heavy fire pouring from that quarter, Benning’s brigade was pressed to the thickening line at the angle, and G. T. Anderson’s was put in support of the battle growing against Hood’s right.

There’s no mention in either Law’s or Longstreet’s accounts of the two men arguing the matter face-to-face.

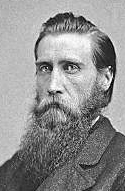

Division commander John Bell Hood (1831-79), in his posthumously-published memoir, gave this version of events, recounted in a letter he’d written to Longstreet a decade after the conflict:

Division commander John Bell Hood (1831-79), in his posthumously-published memoir, gave this version of events, recounted in a letter he’d written to Longstreet a decade after the conflict:

A third time I despatched one of my staff [to Longstreet] to explain fully in regard to the situation, and suggest that you had better come and look for yourself. I selected, in this instance, my adjutant-general, Colonel Harry Sellers, whom you know to be not only an officer of great courage, but also of marked ability. Colonel Sellers returned with the same message, ‘General Lee’s orders are to attack up the Emmetsburg road.’ Almost simultaneously. Colonel Fairfax, of your staff, rode up and repeated the above orders.

After this urgent protest against entering the battle at Gettysburg, according to instructions — which protest is the first and only one I ever made during my entire military career — I ordered my line to advance and make the assault.

As my troops were moving forward, you [Longstreet] rode up in person; a brief conversation passed between us, during which I again expressed the fears above mentioned, and regret at not being allowed to attack in flank around Round Top. You answered to this effect, ‘ We must obey the orders of General Lee.’ I then rode forward with my line under a heavy fire. In about twenty minutes, after reaching the peach orchard, I was severely wounded in the arm, and borne from the field.

Hood’s account is the earliest of the three, and closest to the scene in the film. But while it does recount a face-to-face meeting between him and Longstreet, it differs from the movie encounter in two critical aspects. First, Hood makes it clear that it was Longstreet who came to him, not the other way around. More important, when they did meet, the issue had already been decided, and Hood’s Division was already advancing. At this point, the decision to commit his troops to a frontal assault was final — “I again expressed the fears above mentioned, and regret at not being allowed to attack in flank around Round Top.” Like Law, Hood says his formal protest was made through staff officers earlier, not directly to Longstreet himself, and there’s no suggestion that when they did met, their exchange was anywhere near as heated as depicted in the movie.

So what really happened? All three accounts are pretty consistent, given the passage of years, and none has Hood riding over to his corps commander to make his plea in person. (Indeed, to have absented himself from his division to do so during a battle, in fact, might have been seen as dereliction; generals are surrounded by staff officers and couriers for just that purpose.) If the two discussed it at all in person, as Hood describes, it was after the matter had already been settled and his division’s regiments were on the move.

Kevin has mentioned before how another important Civil War film, Glory, both highlighted and badly over-simplified the “pay crisis” that enveloped the 54th Massachusetts and other early black regiments. Virtually all films of that sort have to simplify events, compress timelines and (sometimes) create composite characters to advance the story at a regular pace, and help the audience follow the plot. It’s just a fact of story-telling on film.

I don’t especially fault Ron Maxwell, who both directed Gettysburg and wrote the screenplay, for handling this part of the story, in this way. It neatly, and dramatically, encapsulates the real-life conflict between Old Pete and Sam Hood in a way that more-historically-accurate shots of staff officers galloping back and forth across the Pennsylvania countryside could never achieve. It’s more effective storytelling, and it accurately reflects the positions of the principals. But even when, as in this case, it speaks to a larger truth, one should never confuse it with the truth.

And I still love that scene.

__________

Evilizing General Sherman

Many people have made the point that, for all their alleged disdain for “revisionist” history, those who hold to a “Southern” view of the war are themselves embracing an explicitly revisionist historical narrative. It’s a narrative that was carefully crafted in the decades following the Civil War to exonerate the Confederate cause, depict Southern leaders in the most flattering and noble way possible, and to undermine or denigrate the Union effort to highlight the contrast. This effort, which lies at the core of the Lost Cause, probably reached its zenith in the second decade of the 20th century. But with a few concessions to modern sensibilities — e.g., “faithful slaves” have now become “black Confederate soldiers” — the narrative remains largely as it was a century ago, and is held dear by many. But great longevity doesn’t make a revisionist narrative any less revisionist.

Now comes the Spring 2012 issue of the Civil War Monitor, and Thom Bassett’s cover story, “Birth of a Demon.” Bassett explains how, through several postwar tours of the South, Sherman was received and honored by both public officials and the citizenry of cities who, present-day conventional wisdom holds, should have held a burning hatred for the man. In New Orleans he was an honored guest at Mardi Gras festivities in 1879, where he was named to the royal court as “Duke of Louisiana.” He was accompanied to the theater there by his old opponent, John Bell Hood, who gave a long speech praising the former Union general. On that same trip Sherman spent three days in Atlanta, where he reported receiving “everywhere nothing but kind and courteous treatment from the highest to the lowest.” Here is what the Atlanta Weekly Constitution said of his visit, on February 4, 1879:

Now comes the Spring 2012 issue of the Civil War Monitor, and Thom Bassett’s cover story, “Birth of a Demon.” Bassett explains how, through several postwar tours of the South, Sherman was received and honored by both public officials and the citizenry of cities who, present-day conventional wisdom holds, should have held a burning hatred for the man. In New Orleans he was an honored guest at Mardi Gras festivities in 1879, where he was named to the royal court as “Duke of Louisiana.” He was accompanied to the theater there by his old opponent, John Bell Hood, who gave a long speech praising the former Union general. On that same trip Sherman spent three days in Atlanta, where he reported receiving “everywhere nothing but kind and courteous treatment from the highest to the lowest.” Here is what the Atlanta Weekly Constitution said of his visit, on February 4, 1879:

Yesterday General Sherman returned to the scene of this destruction and disaster, and looked upon the answer that our people have made to his torch. A proud city, prosperous almost beyond compare, throbbing with vigor and strength, and rapturous with the thrill of growth and expansion, stands before him. A people brave enough to bury their hatreds in the ruins his hands have made, and wise enough to turn their passion towards recuperation rather than revenge. . . .

It would be a stretch to say that Sherman was popular across the South, but it was clear that he was not considered the reviled monster he later was to become in some quarters.

So what changed? In 1881 Jefferson Davis published his defense of secession, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, and used it to excoriate Sherman to a degree that no other senior Confederate had, including men who’d actually faced him across the lines, like Hood. Bassett:

[Davis] called Sherman’s decision to remove Atlanta’s civilian population after the city’s surrender unparalleled in modern warfare. “Since Alva’s atrocious cruelties to the noncombatant populations of the Low Countries in the Sixteenth Century, the history of war records no instance of such barbarous cruelty as that which this order was designed to perpetrate.” . . . Davis made perfectly clear whom he considered responsible for these depredations, thundering that Sherman had issued an “inhuman order” and that the “cowardly dishonesty of its executioners was in perfect harmony with the temper and spirit of the order.”

Davis’ accusations struck a chord with Southerners, who by this time had come to see the former Confederate president as the living embodiment of the Confederate cause. Sherman provided a useful focus for the lingering resentments of former Confederates, and Davis’ book proved to be the essential catalyst. Sherman came to be reviled not so much because Southerners viewed him that way of their own experience, but because Jeff Davis told them they should.

Sherman and Davis would continue to spar over Davis’ accusations for the rest of their lives — Davis died in 1889, Sherman in 1891 — but the preferred Confederate narrative was set. Despite fifteen postwar years of enjoying relatively good relations with Southerners and an ongoing affinity for the South, Sherman was successfully cast as something inhuman, a monster, responsible for depredations nearly unmatched in human history to that point. Many today still believe that; more, in fact, than seem to have believed it in the years immediately following the war itself.

Whatever one happens to think of Uncle Billy, Bassett’s article really is a must-read as a practical example of the way historical narratives are shaped, refined, and sometimes abused. Civil War Monitor Editor-in-Chief Terry Johnston and his team have been working hard to challenge conventional ways of looking at the conflict, and Thom Bassett’s piece is an excellent example of how they’re doing just that.

It really is not your father’s Civil War magazine.

__________

5 comments