Yankees in the Attic

Not my attic, as it happens, but my wife’s. It’s hardly a surprise, but it’s good to be able to confirm specific names and dates, rather than some vague understanding passed down by oral history. It appears that her great-grandfather’s two older brothers, James Bradley Ridge and George B. Ridge, both fought for the Union during the Civil War. Bradley, aged about 17, enlisted in Co. K of the 5th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry on July 21, 1861, and served with the regiment until discharged on July 5, 1865. His older brother George, age about 19, enlisted in the same company in January 1862, and served through the end of the war. He was promoted to Corporal in June 1865, and mustered out of the regiment on July 19, 1865 at Alexandria, Virginia.

The 5th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry was originally composed of companies formed in response to that state’s governor’s call for volunteers in April 1861. These units were disbanded after Lincoln’s call for 75,000 troops in May 1861, and reorganized themselves as the First Regiment, Colt’s Revolving Rifles, with famed gun maker Samuel Colt as their prospective colonel. The new regiment was quartered on the grounds of the Colt Patent Fire Arms Company at Hartford, but when Colt determined that the regiment should enlist as regulars, the new recruits refused. So the First Regiment of Colt’s Revolving Rifles was disbanded (again) and immediately reformed (again) as the 5th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry. And they never did get their Colt Revolving Rifles.

As part of the Army of the Potomac, the 5th Connecticut took part in Pope’s campaign in northern Virginia, and were heavily engaged at the Battle of Cedar Mountain on August 9, 1862. On that day Pope’s army ran smack into that of Stonewall Jackson. After initially pushing back the Confederate line, a swift counterattack by A.P. Hill’s troops turned the course of the action late in the day. The 5th Connecticut, in the thick of the fighting near a local landmark known as “the cabin” (below), lost 48 men killed or mortally wounded, 67 wounded and 64 captured, or 179 of the 380 men present — 47.1% casualties. The regimental history notes ruefully that these losses were “as large as all the rest of its battle service put together,” and among the highest of any Connecticut regiment during the entire war.

“Charge of Union troops of the left flank of the army commanded by Genl. Stonewall Jackson at Cedar Mountain,” by Edwin Forbes. Library of Congress.

The regiment was present at Second Manassas (Bull Run), and the following year in the Chancellorsville and Gettysburg campaigns. After Gettysburg, the regiment was transferred to the Army of the Cumberland, where in 1864 it participated in Sherman’s Atlanta campaign. According to its regimental history, the 5th Connecticut led the column of Sherman’s army that marched into Atlanta on September 2, 1864, after that city’s surrender:

September 2d. We all move forward toward the city of Atlanta, leaving our tents standing. Our regiment has the advance, and the Fifth Regiment Connecticut Veteran Volunteers have the honor of being the first Union regiment to march through the streets of the city of Atlanta. We have certainly earned the honor, for we have made a long and tedious campaign, having been 112 days and nights continually under fire, sleeping many nights in the trenches, fighting at every opportunity, always holding the ground and routing those opposed to us, and finishing the campaign with great honor to ourselves, to the State and to the General Government.

General Sherman says that we will rest in the city for thirty days, and I believe him.

Federal troops occupy former Confederate defensive works at Atlanta. A diarist in the 5th Connecticut recorded on September 10, 1864, “have visited the lines of fortification built by ourselves and the rebels around this city, and also looked around the city. Terrible destruction by shot and shell everywhere.” Library of Congress.

The 5th Connecticut went on to participate in Sherman’s “March to the Sea,” and in fighting up through the Carolinas in 1865. Bradley Ridge was reported missing after the Battle of Averasboro in North Carolina in March 1865, but eventually returned to the regiment. (I have not yet received his CSR, so don’t know the specifics, or if he was captured by Confederate forces.)

That particular line of my wife’s family has a long tradition of military service — her grandfather was gassed with the AEF during World War I, her dad served in the wars in Korea and Vietnam, her brother flew on medical evacuation missions during Desert Storm, and so on. Now that list goes a little farther back, still.

_______

Juneteenth, History and Tradition

[This post originally appeared here on June 19, 2010.]

“Emancipation” by Thomas Nast. Ohio State University.

Juneteenth has come again, and (quite rightly) the Galveston County Daily News, the paper that first published General Granger’s order that forms the basis for the holiday, has again called for the day to be recognized as a national holiday:

Those who are lobbying for a national holiday are not asking for a paid day off. They are asking for a commemorative day, like Flag Day on June 14 or Patriot Day on Sept. 11. All that would take is a presidential proclamation. Both the U.S. House and Senate have endorsed the idea.

Why is a national celebration for an event that occurred in Galveston and originally affected only those in a single state such a good idea?

Because Juneteenth has become a symbol of the end of slavery. No matter how much we may regret the tragedy of slavery and wish it weren’t a part of this nation’s story, it is. Denying the truth about the past is always unwise.

For those who don’t know, Juneteenth started in Galveston. On Jan. 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. But the order was meaningless until it could be enforced. It wasn’t until June 19, 1865 — after the Confederacy had been defeated and Union troops landed in Galveston — that the slaves in Texas were told they were free.

People all across the country get this story. That’s why Juneteenth celebrations have been growing all across the country. The celebration started in Galveston. But its significance has come to be understood far, far beyond the island, and far beyond Texas.

This is exactly right. Juneteenth is not just of relevance to African Americans or Texans, but for all who ascribe to the values of liberty and civic participation in this country. A victory for civil rights for any group is a victory for us all, and there is none bigger in this nation’s history than that transformation represented by Juneteenth.

But as widespread as Juneteenth celebrations have become — I was pleased and surprised, some years ago, to see Juneteenth celebration flyers pasted up in Minnesota — there’s an awful lot of confusion and misinformation about the specific events here, in Galveston, in June 1865 that gave birth to the holiday. The best published account of the period appears in Edward T. Cotham’s Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, from which much of what follows is abstracted.

The United States Customs House, Galveston.

On June 5, Captain B. F. Sands entered Galveston harbor with the Union naval vessels Cornubia and Preston. Sands went ashore with a detachment and raised the United States flag over the federal customs house for about half an hour. Sands made a few comments to the largely silent crowd, saying that he saw this event as the closing chapter of the rebellion, and assuring the local citizens that he had only worn a sidearm that day as a gesture of respect for the mayor of the city.

Site of General Granger’s headquarters, southwest corner of 22nd Street and Strand.

A large number of Federal troops came ashore over the next two weeks, including detachments of the 76th Illinois Infantry. Union General Gordon Granger, newly-appointed as military governor for Texas, arrived on June 18, and established his headquarters in Osterman Building (now gone) on the southwest corner of 22nd and Strand. The provost marshal, which acted largely as a military police force, set up in the Customs House. The next day, June 19, a Monday, Granger issued five general orders, establishing his authority over the rest of Texas and laying out the initial priorities of his administration. General Orders Nos. 1 and 2 asserted Granger’s authority over all Federal forces in Texas, and named the key department heads in his administration of the state for various responsibilities. General Order No. 4 voided all actions of the Texas government during the rebellion, and asserted Federal control over all public assets within the state. General Order No. 5 established the Army’s Quartermaster Department as sole authorized buyer for cotton, until such time as Treasury agents could arrive and take over those responsibilities.

It is General Order No. 3, however, that is remembered today. It was short and direct:

Headquarters, District of Texas

Galveston, Texas, June 19, 1865General Orders, No. 3

The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there ro elsewhere.

By order of

Major-General Granger

F. W. Emery, Maj. & A. . G.

What’s less clear is how this order was disseminated. It’s likely that printed copies were put up in public places. It was published on June 21 in the Galveston Daily News, but otherwise it is not known if it was ever given a formal, public and ceremonial reading. Although the symbolic significance of General Order No. 3 cannot be overstated, its main legal purpose was to reaffirm what was well-established and widely known throughout the South, that with the occupation of Federal forces came the emancipation of all slaves within the region now coming under Union control.

The James Moreau Brown residence, now known as Ashton Villa, at 24th & Broadway in Galveston. This site is well-established in local tradition as the site of the original Juneteenth proclamation, although direct evidence is lacking.

Local tradition has long held that General Granger took over James Moreau Brown’s home on Broadway, Ashton Villa, as a residence for himself and his staff. To my knowledge, there is no direct evidence for this. Along with this comes the tradition that the Ashton Villa was also the site where the Emancipation Proclamation was formally read out to the citizenry of Galveston. This belief has prevailed for many years, and is annually reinforced with events commemorating Juneteenth both at the site, and also citing the site. In years past, community groups have even staged “reenactments” of the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation from the second-floor balcony, something which must surely strain the limits of reasonable historical conjecture. As far as I know, the property’s operators, the Galveston Historical Foundation, have never taken an official stand on the interpretation that Juneteenth had its actual origins on the site. Although I myself have serious doubts about Ashton Villa having having any direct role in the original Juneteenth, I also appreciate that, as with the band playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee” as Titanic sank beneath the waves, arguing against this particular cherished belief is undoubtedly a losing battle.

Assuming that either the Emancipation Proclamation (or alternately, Granger’s brief General Order No. 3) was formally, ceremonially read out to the populace, where did it happen? Charles Waldo Hayes, writing several years after the war, says General Order No. 3 was “issued from [Granger’s] headquarters,” but that sounds like a figurative description rather than a literal one. My bet would not be Ashton Villa, but one of two other sites downtown already mentioned: the Osterman Building, where Granger’s headquarters was located and where the official business of the Federal occupation was done initially, or at the United States Customs House, which was the symbol of Federal property both in Galveston and the state as a whole, and (more important still) was the headquarters of Granger’s provost marshal, Lieutenant Colonel Rankin G. Laughlin of the 94th Illinois Infantry. It’s easy to imagine Lt. Col. Laughlin dragging a crate out onto the sidewalk in front of the Customs House and barking out a brief, and somewhat perfunctory, read-through of all five of the general’s orders in quick succession. No flags, no bands, and probably not much of a crowd to witness the event. My personal suspicion is that, were we to travel back to June 1865 and witness the origin of this most remarkable and uniquely-American holiday, we’d find ourselves very disappointed in how the actual events played out at the time.

Maybe the Ashton Villa tradition is preferable, after all.

Living Talismans of a Mythic Past

A recent news item out of Tarrant, Alabama highlights a man named Tyus Denney, honored as a “Real Son” of the Confederacy, meaning that his father was actually a Confederate veteran. (The UDC has a similar designation for “Real Daughters,” and the Sons of Union Veterans also has a “Real Sons” recognition.) Such people are interesting to me because they demonstrate how close the Civil War actually is to us in terms of the human life span. As the comedian Louis C.K. said on Leno a while back, in reference to the times that’s passed since emancipation, “that’s two 70-year-old ladies livin’ and dyin’, back-to-back.” His arithmetic is off, but the point remains: it wasn’t really all that long ago.

“My daddy was 80 when I come in this world,” said Denney at his home in Tarrant, where he keeps 10 beehives in the backyard to harvest honey. “I was 13 years old when he died. He never did talk about the Civil War. He never said nothing about it.”

But his father, Thomas Jefferson Denney, is heavily documented as having fought in the Civil War, as part of Company H in the 31st Alabama Infantry regiment. He was captured by Union forces on June 15, 1864 near Marietta, Ga., and held prisoner at Rock Island Barracks, Illinois, where he signed an oath of allegiance to the United States upon his release on June 18, 1865.

That makes Tyus Denney one of the last living “real sons” of Confederate veterans, according to the Sons of Confederate Veterans, an organization made up mostly of descendants several generations further removed from their Confederate ancestors. Denney’s sister, Vivian Smith, 88, of Cullman, is one of the last living “real daughters” of Confederate veterans. . . .

In 1986, the Sons of Confederate Veterans made Denney a lifetime member, not required to pay dues. He sometimes goes to Civil War reenactments.

“I just watch,” he said. “I don’t know nothing about the war.”

I mean no disrespect to Mr. Denney, but his example highlights a fundamental conceit of heritage groups (of all stripes), that linear descent from people who lived through historic events imparts a particular wisdom or understanding of those events in people living today. It doesn’t, but it does seem to make people believe they speak with authority on all sorts of things they haven’t the foggiest clue about. I once saw a comment on a message board, seething with righteous indignation, to the effect that neither Robert or Mary Custis Lee ever owned or oversaw slaves; the commenter asserted as his authority the fact that he held a life membership in the SCV.

Unlike that fool, Tyus Denney at least has the candor and self-awareness to acknowledge what he knows and what he doesn’t.

Some Civil War soldiers wrote letters and diaries that have survived down to the present; most did not. Some Civil War soldiers wrote memoirs decades later about their experiences in the war; most did not. Many veterans passed on stories about the war to their children and grandchildren, that have filtered down (with changes unknown) through the generations to the present. All of these things can, in one way or another, shape our understanding if these mens’ experiences as individuals. But even in the best case, they tell us very little about events outside that man’s observation, they way he wanted others to understand them.

But more generally, the mere fact of being kin to a Civil War soldier doesn’t impart any particular wisdom or insight into that conflict. It’s an accident of birth, and conveys no special knowledge or understanding of the past. What intrinsic commodity, exactly, do men like Mr. Denney convey to modern Americans by virtue of their (and their fathers’) longevity? What do we know or understand or believe about the war that we would not, were they not here? How does simple ancestry weigh on the scale against academic study of the conflict when it comes to insight and knowledge? Does direct descent from a Confederate veteran, whom one never knew, impart a fuller understanding of the period that collateral descent from the same man would?

Or are men like Mr. Denny only talismans, valued as living links to a past that is as much imagined as it is recorded?

____________

Image: Parole document of 15-year-old Private Thomas Denny, 31st Alabama Infantry, Rock Island Barracks, June 18, 1865. Via Footnote.

“Ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave.”

It would be a shame to let April slip by without a mention of Texas State Senate Resolution No. 526, which designates this month as Texas Confederate History and Heritage Month. The resolution uses a lot of boilerplate language (including an obligatory mention of “politically correct revisionists”), and also makes the assertion that “ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave.” This is a common argument among Confederate apologists, part of a larger effort to minimize or eliminate the institution of slavery as a factor in secession and the coming of the war, and thus make it possible to maintain the notion that Southern soldiers, like the Confederacy itself, were driven by the purest and noblest values to defend home and hearth. Slavery played no role it the coming of the war, they say; how could it, when less than two percent (four percent, five percent) actually owned slaves? In fact, they’d say, their ancestors had nothing at all to do with slavery.

But it’s wrong.

It’s true that in an extremely narrow sense, only a very small proportion of Confederate soldiers owned slaves in their own right. That, of course, is to be expected; soldiering is a young man’s game, and most young men, then and now, have little in the way of personal wealth. As a crude analogy, how many PFCs and corporals in Iraq and Afghanistan today own their own homes? Not many.

But even if it is narrowly true, it’s a deeply misleading statistic, cited religiously to distract from the much more relevant number, the proportion of soldiers who came from slaveholding households. The majority of the young men who marched off to war in the spring of 1861 were fully vested in the “peculiar institution.” Joseph T. Glatthaar, in his magnificent study of the force that eventually became the Army of Northern Virginia, lays out the evidence.

Even more revealing was their attachment to slavery. Among the enlistees in 1861, slightly more than one in ten owned slaves personally. This compared favorably to the Confederacy as a whole, in which one in every twenty white persons owned slaves. Yet more than one in every four volunteers that first year lived with parents who were slaveholders. Combining those soldiers who owned slaves with those soldiers who lived with slaveholding family members, the proportion rose to 36 percent. That contrasted starkly with the 24.9 percent, or one in every four households, that owned slaves in the South, based on the 1860 census. Thus, volunteers in 1861 were 42 percent more likely to own slaves themselves or to live with family members who owned slaves than the general population.

The attachment to slavery, though, was even more powerful. One in every ten volunteers in 1861 did not own slaves themselves but lived in households headed by non family members who did. This figure, combined with the 36 percent who owned or whose family members owned slaves, indicated that almost one of every two 1861 recruits lived with slaveholders. Nor did the direct exposure stop there. Untold numbers of enlistees rented land from, sold crops to, or worked for slaveholders. In the final tabulation, the vast majority of the volunteers of 1861 had a direct connection to slavery. For slaveholder and nonslaveholder alike, slavery lay at the heart of the Confederate nation. The fact that their paper notes frequently depicted scenes of slaves demonstrated the institution’s central role and symbolic value to the Confederacy.

More than half the officers in 1861 owned slaves, and none of them lived with family members who were slaveholders. Their substantial median combined wealth ($5,600) and average combined wealth ($8,979) mirrored that high proportion of slave ownership. By comparison, only one in twelve enlisted men owned slaves, but when those who lived with family slave owners were included, the ratio exceeded one in three. That was 40 percent above the tally for all households in the Old South. With the inclusion of those who resided in nonfamily slaveholding households, the direct exposure to bondage among enlisted personnel was four of every nine. Enlisted men owned less wealth, with combined levels of $1,125 for the median and $7,079 for the average, but those numbers indicated a fairly comfortable standard of living. Proportionately, far more officers were likely to be professionals in civil life, and their age difference, about four years older than enlisted men, reflected their greater accumulated wealth.

The prevalence of slaveholding was so pervasive among Southerners who heeded the call to arms in 1861 that it became something of a joke; Glatthaar tells of an Irish-born private in a Georgia regiment who quipped to his messmates that “he bought a negro, he says, to have something to fight for.”

While Joe Glatthaar undoubtedly had a small regiment of graduate assistants to help with cross-indexing Confederate muster rolls and the 1860 U.S. Census, there are some basic tools now available online that will allow anyone to at least get a general sense of the validity of his numbers. The Historical Census Browser from the University of Virginia Library allows users to compile, sort and visualize data from U.S. Censuses from 1790 to 1960. For Glatthaar’s purposes and ours, the 1860 census, taken a few months before the outbreak of the war, is crucial. It records basic data about the free population, including names, sex, approximate age, occupation and value of real and personal property of each person in a household. A second, separate schedule records the name of each slaveholder and lists the slave he or she owns. Each slave is listed by sex and age; names were not recorded. The data in the UofV online system can be broken down either by state or counties within a state, and make it possible to compare one data element (e.g., households) with another (slaveholders) and calculate the proportions between them.

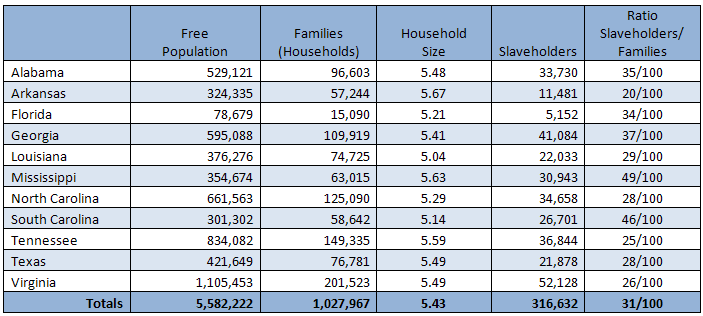

In the vast majority of cases, each household (termed a “family” in the 1860 document, even when the group consisted of unrelated people living in the same residence) that owned slaves had only one slaveholder listed, the head of the household. It is thus possible to compare the number of slaveholders in a given state to the numbers of families/households, and get a rough estimation of the proportion of free households that owned at least one slave. The numbers varies considerably, ranging from (roughly) 1 in 5 in Arkansas to nearly 1 in 2 in Mississippi and South Carolina. In the eleven states that formed the Confederacy, there were in aggregate just over 1 million free households, which between them represented 316,632 slaveholders—meaning that somewhere between one-quarter and one-third of households in the Confederate States counted among its assets at least one human being.

The UofV system also makes it possible to generate maps that show graphically the proportion of slaveholding households in a given county. This is particularly useful in revealing political divisions or disputes within a state, although it takes some practice with the online query system to generate maps properly. Here are county maps for all eleven Confederate states, with the estimated proportion of slaveholding families indicated in green — a darker color indicates a higher density: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, All States.

Observers will note that the incidence of slaveholding was highest in agricultural lowlands, where rivers provided both transportation for bulk commodities and periodic floods that replenished the soil, and lowest in mountainous regions like Appalachia. The map of Virginia, in particular, goes a long way to explaining the breakup of that state during the war.

Obviously this calculation is not perfect. There are a couple of burbles in the data where populations are very low, for example Mississippi, where the census recorded two very sparsely-populated counties having more slaveholders than families (possible, but unlikely), or on the Texas frontier, where the data maps the finding that almost every family probably included a slaveholder. But in spite of its imperfections, it nonetheless presents a picture that more accurately describes the presence of slaveholding in the everyday lives – indeed, under the same roof – of citizens of the Confederate States than the much smaller number of slave owners does.

Aaron Perry, whose seven slaves are enumerated above in an excerpt from the 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedule, illustrates the point. Perry, a Texas State Representative who raised hogs and corn in Limestone County (east of present-day Waco) had two sons, William and Mark (or Marcus), living with him at the farm at the time of the census. The elder Perry owned $3,000 worth of land, and nearly four times that in personal property, most of which must have been represented in those seven slaves. When the war came, both sons joined the Eighth Texas Cavalry, the famed Terry’s Rangers. Because neither of the sons – aged 21 and 17 respectively at the time of the census – held formal, legal title to a bondsman, Confederate apologists would claim that they are among the “ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers [that] never owned a slave,” and, by implication, therefore had no interest or motivation to protect the “peculiar institution.” Nonetheless, it was slave labor that made their father’s farm (and their inheritance) a going concern. It was slave labor that, in one way or another, provided the food they ate, the shelter over their heads, the money in their pockets, the clothes they wore, and formed the basis of wealth they would inherit someday. And when they went to war, it was slave labor that made it possible for them to bring with them the mounts and sidearms that Texas cavalrymen were expected to provide for themselves. While the Perry boys left no record of their personal thoughts or motivations upon enlisting, the notion that these two young men must have had no interest, no personal stake, in the preservation of slavery as an institution is simply asinine on its face.

You don’t have to talk to a Confederate apologist long before you’ll be told that only a tiny fraction of butternuts owned slaves. (This is usually followed immediately by an assertion that the speaker’s own Confederate ancestors never owned slaves, either.) The number ascribed to Confederate soldiers as a whole varies—two percent, five percent—but the message is always the same, that those men 150 years had nothing to do with the peculiar institution, they had no stake in it, and that it certainly played no role whatever in their personal motivations or in the Confederacy’s goals in the war. But such a blanket disassociation between Confederate soldiers and the “peculiar institution” is simply not true in any meaningful way. Slave labor was as much a part of life in the antebellum South as heat in the summer and hog-killing time in the late fall. Southerners who didn’t own slaves could not but avoid coming in regular, frequent contact with the institution. They hired out others’ slaves for temporary work. They did business with slaveholders, bought from or sold to them. They utilized the products of others’ slaves’ labor. They traveled roads and lived behind levees built by slaves. Southerners across the Confederacy, from Texas to Florida to Virginia, civilian and soldier alike, were awash in the institution of slavery. They were up to their necks in it. They swam in it, and no amount of willful denial can change that.

Coming up: Did non-slaveholding Southerners have a stake in fighting to defend the “peculiar institution?”

_____________________

Images: Top, list of seven slaves belonging to Texas State Representative Aaron Perry of Limestone County, Texas, from the 1860 U.S. Census slave schedules, via Ancestry. Below, central image on the face of a Confederate States of America $100 note,issued at Richmond in 1862, featuring African Americans working in the field, via The Daily Omnivore Blog.

This post is adapted from one originally appearing in The Atlantic online in August 2010.

Ancestry Continues to Impress

I’ve been using Ancestry.com for a year or so now. While it’s been a tremendous help in tracing my own family lineage, it’s become invaluable in tracking some of the people I’ve discussed here on the blog. Even if I never looked up another family member again, I’d still consider it worthwhile. It’s not cheap, but for the blogging I do, access to online resources like Ancestry, Footnote and GenealogyBank are simply part of the price of admission.

But they continue to impress with new additions. Who would’ve though of this:

The Military Headstone Archive: a one-of-a-kind new collection

Ancestry.com has undertaken an ambitious project to chronicle military headstones, starting with 33 Civil War cemeteries. This interactive collection lets you search gravesites, attach headstone images to your tree and find GPS coordinates for your soldier ancestor’s final resting place. You’ll also get rich context about some of the Civil War’s most important battlefield cemeteries.

In practice, the system is a little dodgy. As a test, I looked up several headstone photos on Flickr, more-or-less- at random, and tried to find them in the new database. I couldn’t locate the first few, but did find that of David Mowery listed as below, at Shiloh:

. . . and this one for William E. Miller at Gettysburg:

One more tool in the collection, and a welcome one.

______________

Brief Updates

Things have been busy of late here, and postings limited. So here are a few quick updates.

If you haven’t heard, Kevin’s blog, Civil War Memory, was selected for digital archiving by the Library of Congress as part of their efforts to document the Civil War Sesquicentennial. How cool is that?

A week ago Friday, long after normal business hours, I e-mailed the Texas State Library in Austin to request a Confederate pension file. The official turnaround time is 4-6 weeks, but this Friday (five business days) I got an e-mail that the copies were already in the mail. Props to the library staff in Austin.

I’ve added two new blogs to the roll at right, Civil War Medicine (and Writing) and Notre Dame and the Civil War. Both are written by Jim Schmidt, a Civil War historian who’s published several very well-received works, including Notre Dame and the Civil War: Marching Onward to Victory, Lincoln’s Labels: America’s Best Known Brands and the Civil War, and the edited volume, Years of Change and Suffering: Modern Perspectives on Civil War Medicine. Welcome to the blogroll, Jim. It’s because of people like Jim that my Amazon purchases ran to thirteen damn pages last year.

Finally, just up the road a ways, a Reconstruction-era Freedman’s settlement has been formally added to the National Register of Historic Places.

______________

Image: Sketch of a “double-ender” Union gunboat by A. R. Waud. Library of Congress.

Richard Quarls and the Dead Man’s Pension

Kevin recently highlighted a story done by a local news station in Florida on Richard Quarls, in honor of Black History Month. Quarls is one of the better-known “black Confederate soldiers,” and in 2003 had a Confederate headstone placed over his grave by the local SCV and UDC groups.

Kevin recently highlighted a story done by a local news station in Florida on Richard Quarls, in honor of Black History Month. Quarls is one of the better-known “black Confederate soldiers,” and in 2003 had a Confederate headstone placed over his grave by the local SCV and UDC groups.

In watching the video it occurred to me that, as presented, there are two narratives being told in the segment about Richard Quarls. One, as told by his great-granddaughter, Mary Crockett, is that of a slave who accompanied his master’s son to war. Ms. Crockett’s account, passed through her family, is clear about his status and role in the war, recounting that “when the master’s son got shot, and fell, [Quarls] picked up the gun, started firing the gun, and defending him while he laid on the ground.” The son is identified here as H. Middleton Quarles, who was killed in fighting at Maryland Gap, Maryland on September 13, 1862. It may have been in that action that Richard Quarls picked up Private Quarles’ rifle. There’s no reason to doubt Ms. Crockett’s account of her great-grandfather’s experience although, as always, family reminiscences are invariably subject to the vagaries of oral traditions passed from one generation to the next.

The second narrative is that overlaid by the SCV, which “discovered” Quarls’ military service and sponsored the headstone and memorial service. This second narrative is largely reflected in the dialogue of the news report, which is sprinkled with dramatic-sounding but vague phrases that blur the distinction between soldier and servant, slave and free. We are cautioned that “historians disagree about their numbers and how they served,” but also assured that “he may have been a servant and rifleman.” It’s suggested that he may have fought in thirty-three battles, and the viewer is told that at the end of the war Quarls was “honorably discharged.” It’s an impressive story to a general audience, but the historian immediately notices that there are very, very few specific facts presented that can be cross-checked against primary sources.

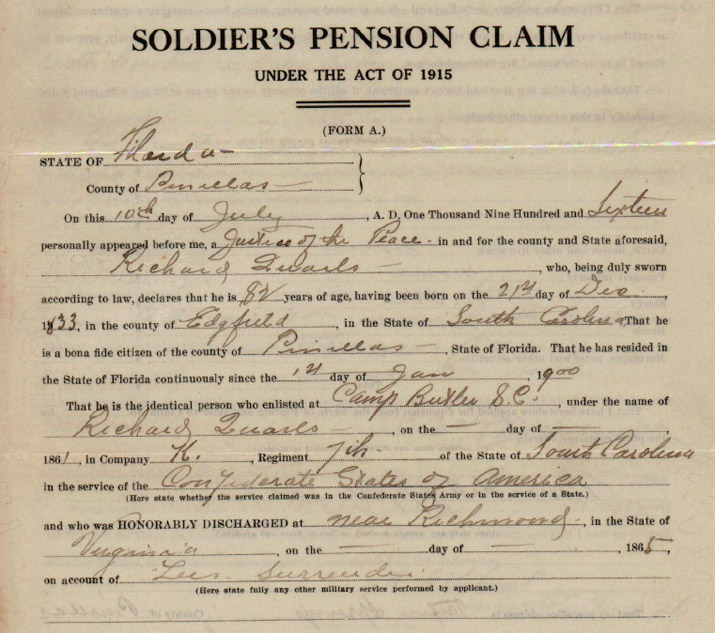

As noted in the video clip, the key element in identifying Quarls’ supposed service as a soldier is his pension record from the State of Florida (10MB PDF). The pitfalls of working with Confederate pension records have been discussed in detail elsewhere, and generally speaking, are less than fully-reliable in determining an individual’s status in 1861-65. They are particularly problematic on the case of Richard Quarls, and actually raise more questions about his wartime service than they answer.

Quarls applied for a pension in Pinellas County, Florida on July 10, 1916. On the first page of the application, he claims that he enlisted in Company K, 7th South Carolina Infantry, at Camp Butler, South Carolina, sometime in 1861. He gives his name upon enlistment as Richard Quarls. He claims to have been discharged in 1865 “near Richmond” Virginia, in 1865, on account of “Lee’s surrender.” The inference is that Quarls served almost the entire war with the 7th South Carolina Infantry. Quarl’s service claims were attested to by two witnesses, T. B. and O. W. Lanier. Both testified to have known Quarls during the war, affirmed his membership in the unit, and that they witnessed his full service as described in the application. These basic elements of his record during the war, claimed on the initial application, appear to have been accepted without question by the SCV, and form the wartime history of Richard Quarls that is now repeated as historic fact, his story being picked up by even non-Civil War authors, including Ann Coulter. (Coulter says Quarls’ grave was unmarked before the installation of the SCV’s stone, which is not true.) In fact, those self-same pension records cast serious doubt on much of what is “known” about Richard Quarls’ service during the Civil War.

Jubilo! on the Appeal of Black Confederates to African Americans

A new blog came online a few weeks back, that I want to highlight because of some very smart writing by a blogger going by the handle lunchcountersitin. Jubilo! The Century of Emancipation deals with much more than the Civil War, but as the central event in American history during the nineteenth century, that conflict gets particular attention. Here’s what strikes me as an insightful read on the phenomenon of modern-day African Americans embracing Southron Heritage™ groups’ designation of their ancestors as Confederate soldiers, willingly fighting for the Confederate cause:

We’ve seen this before: black families filled with honor at the recognition given to their enslaved ancestors, for the reason that those ancestors somehow fought for what was a pro-slavery regime. The sense of conflict inherent in that is hardly mentioned. I got to thinking: how is it that so many black families ignore these details of their ancestors’ lives, status, and circumstances? Why is it that they are not addressing a key part of the story? After a little bit of thought, the answer was obvious. Black folks are like everyone else: they want to feel that their ancestors were heroes.

Simply put, there is no honor or glory in acknowledging that a long deceased relative was near a battlefield solely to do menial work as act of submission and service to a slave master. People would much rather believe that their ancestors were called to fight – which would be a recognition of their manhood, of their worthiness to do battle, and of their willingness to make the ultimate sacrifice.

But here’s the rub: if these slaves were in fact recognized for their manhood and worthiness – then why were they slaves in the first place? The reality is, black men were seen as degraded, to use a common term of the era, and subservient. Loyalty, not the capacity for courage, was most valued in a slave. After all, a bondsman who was intrepid enough to flee for his freedom – and perhaps fight for the Union – was of no use to a slavemaster on the battlefield.

But people of today want to see their ancestors through their own eyes, and they want to see those ancestors as brave and courageous. This focus on “bravery not slavery” dovetails perfectly with the “heritage not hate” narrative of groups like the Sons of Confederates Veterans. By maintaining an unspoken rule to avoid the unspeakable – the horrors of slavery and the contradiction of a slave fighting for a slave nation – both sides get to honor their ancestors without pondering the issues this “service” raises.

Obviously this is generalizing, and as such can’t really be ascribed to this or that specific descendant. People were complicated in 1865, and they’re complicated in 2011. But on a human level, it makes a lot of sense that this is at least part of the equation.

What Did You Think Would Happen, Colonel Perry?

On January 28, 1861, seventy members of the Texas House of Representatives voted to endorse a convention to determine whether Texas should follow South Carolina, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia and Louisiana out of the Union. Only nine representatives voted “nay.” Though the vote was nominally just to authorize the convention, the outcome of such a meeting was a forgone conclusion, and the House vote was, to all intents and purposes, a vote on secession itself.

The Texas Senate passed the resolution that same day, by a vote of 25 to 5. Governor Sam Houston, who opposed secession and would soon be removed from office as a result, signed off on the resolution on February 4, with an appended notation cautioning the convention “against the assumption of any powers on the part of said convention, beyond the reference of the question of a longer connection of Texas with the Union to the people.” It was a moot gesture; the Secession Convention had been called to order in the Capitol the same day the Legislature voted to approve it, and had adopted an ordinance of secession on February 1. The following day the convention adopted its Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union. Texas’ secession was already a fait accompli.

My great-great-great-grandfather, Aaron Perry, was one of the men in the House of Representatives who voted in favor of the resolution to authorize a secession convention. He was born in North Carolina around 1804, lived for a time in Alabama, and moved to Texas in 1846. He farmed in Limestone County, near present-day Waco. In the 1850 U.S. Census non-population schedules, Perry is shown as farming 625 acres, most of which was left uncleared for raising hogs. In the previous season he’d produced 1,500 bushels of corn as well, most of which I suspect went to hog feed before killing time in the fall. By the time of the 1860 census, the value of his land holdings (which may have been expanded in the preceding decade) had grown to $3,000, and the value of his personal property had grown to $11,150. Much of this latter number represented the value of seven slaves he held.

He was known as “Colonel” Perry, although I don’t know what military service of his such a title would be based on. He was active in politics, serving as a delegate from Limestone County to the Texas Democratic Convention in 1857. Later that year he began serving the first of two terms (1857-61) in the Texas House of Representatives. By the time his second term ended, Texas had seceded from the Union, Sumter had fallen, and the Battle of Manassas had been fought. Aaron Perry disappears from the historical record at that point, so far as I’ve been able to determine; I don’t know how or when he died. Two of his sons, William and Marcus, went on to serve in the Confederate cavalry. Both survived the war.

There are lots of Confederate soldiers in my family tree. But “Old Colonel Perry,” as he was recalled in the family, is the only direct ancestor I know of who was a civil official, a legislator, who took an affirmative step toward secession. He voted “yay.” I wonder what he thought the ultimate outcome of that would be.

__________________

Image: Texas State Capitol, Austin, in the 1870s. Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library.

3 comments