“Ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave.”

It would be a shame to let April slip by without a mention of Texas State Senate Resolution No. 526, which designates this month as Texas Confederate History and Heritage Month. The resolution uses a lot of boilerplate language (including an obligatory mention of “politically correct revisionists”), and also makes the assertion that “ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave.” This is a common argument among Confederate apologists, part of a larger effort to minimize or eliminate the institution of slavery as a factor in secession and the coming of the war, and thus make it possible to maintain the notion that Southern soldiers, like the Confederacy itself, were driven by the purest and noblest values to defend home and hearth. Slavery played no role it the coming of the war, they say; how could it, when less than two percent (four percent, five percent) actually owned slaves? In fact, they’d say, their ancestors had nothing at all to do with slavery.

But it’s wrong.

It’s true that in an extremely narrow sense, only a very small proportion of Confederate soldiers owned slaves in their own right. That, of course, is to be expected; soldiering is a young man’s game, and most young men, then and now, have little in the way of personal wealth. As a crude analogy, how many PFCs and corporals in Iraq and Afghanistan today own their own homes? Not many.

But even if it is narrowly true, it’s a deeply misleading statistic, cited religiously to distract from the much more relevant number, the proportion of soldiers who came from slaveholding households. The majority of the young men who marched off to war in the spring of 1861 were fully vested in the “peculiar institution.” Joseph T. Glatthaar, in his magnificent study of the force that eventually became the Army of Northern Virginia, lays out the evidence.

Even more revealing was their attachment to slavery. Among the enlistees in 1861, slightly more than one in ten owned slaves personally. This compared favorably to the Confederacy as a whole, in which one in every twenty white persons owned slaves. Yet more than one in every four volunteers that first year lived with parents who were slaveholders. Combining those soldiers who owned slaves with those soldiers who lived with slaveholding family members, the proportion rose to 36 percent. That contrasted starkly with the 24.9 percent, or one in every four households, that owned slaves in the South, based on the 1860 census. Thus, volunteers in 1861 were 42 percent more likely to own slaves themselves or to live with family members who owned slaves than the general population.

The attachment to slavery, though, was even more powerful. One in every ten volunteers in 1861 did not own slaves themselves but lived in households headed by non family members who did. This figure, combined with the 36 percent who owned or whose family members owned slaves, indicated that almost one of every two 1861 recruits lived with slaveholders. Nor did the direct exposure stop there. Untold numbers of enlistees rented land from, sold crops to, or worked for slaveholders. In the final tabulation, the vast majority of the volunteers of 1861 had a direct connection to slavery. For slaveholder and nonslaveholder alike, slavery lay at the heart of the Confederate nation. The fact that their paper notes frequently depicted scenes of slaves demonstrated the institution’s central role and symbolic value to the Confederacy.

More than half the officers in 1861 owned slaves, and none of them lived with family members who were slaveholders. Their substantial median combined wealth ($5,600) and average combined wealth ($8,979) mirrored that high proportion of slave ownership. By comparison, only one in twelve enlisted men owned slaves, but when those who lived with family slave owners were included, the ratio exceeded one in three. That was 40 percent above the tally for all households in the Old South. With the inclusion of those who resided in nonfamily slaveholding households, the direct exposure to bondage among enlisted personnel was four of every nine. Enlisted men owned less wealth, with combined levels of $1,125 for the median and $7,079 for the average, but those numbers indicated a fairly comfortable standard of living. Proportionately, far more officers were likely to be professionals in civil life, and their age difference, about four years older than enlisted men, reflected their greater accumulated wealth.

The prevalence of slaveholding was so pervasive among Southerners who heeded the call to arms in 1861 that it became something of a joke; Glatthaar tells of an Irish-born private in a Georgia regiment who quipped to his messmates that “he bought a negro, he says, to have something to fight for.”

While Joe Glatthaar undoubtedly had a small regiment of graduate assistants to help with cross-indexing Confederate muster rolls and the 1860 U.S. Census, there are some basic tools now available online that will allow anyone to at least get a general sense of the validity of his numbers. The Historical Census Browser from the University of Virginia Library allows users to compile, sort and visualize data from U.S. Censuses from 1790 to 1960. For Glatthaar’s purposes and ours, the 1860 census, taken a few months before the outbreak of the war, is crucial. It records basic data about the free population, including names, sex, approximate age, occupation and value of real and personal property of each person in a household. A second, separate schedule records the name of each slaveholder and lists the slave he or she owns. Each slave is listed by sex and age; names were not recorded. The data in the UofV online system can be broken down either by state or counties within a state, and make it possible to compare one data element (e.g., households) with another (slaveholders) and calculate the proportions between them.

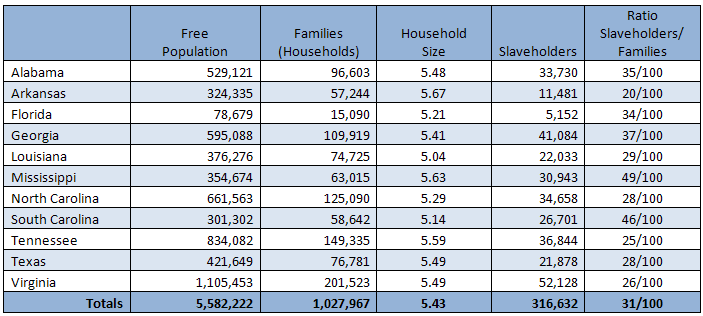

In the vast majority of cases, each household (termed a “family” in the 1860 document, even when the group consisted of unrelated people living in the same residence) that owned slaves had only one slaveholder listed, the head of the household. It is thus possible to compare the number of slaveholders in a given state to the numbers of families/households, and get a rough estimation of the proportion of free households that owned at least one slave. The numbers varies considerably, ranging from (roughly) 1 in 5 in Arkansas to nearly 1 in 2 in Mississippi and South Carolina. In the eleven states that formed the Confederacy, there were in aggregate just over 1 million free households, which between them represented 316,632 slaveholders—meaning that somewhere between one-quarter and one-third of households in the Confederate States counted among its assets at least one human being.

The UofV system also makes it possible to generate maps that show graphically the proportion of slaveholding households in a given county. This is particularly useful in revealing political divisions or disputes within a state, although it takes some practice with the online query system to generate maps properly. Here are county maps for all eleven Confederate states, with the estimated proportion of slaveholding families indicated in green — a darker color indicates a higher density: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, All States.

Observers will note that the incidence of slaveholding was highest in agricultural lowlands, where rivers provided both transportation for bulk commodities and periodic floods that replenished the soil, and lowest in mountainous regions like Appalachia. The map of Virginia, in particular, goes a long way to explaining the breakup of that state during the war.

Obviously this calculation is not perfect. There are a couple of burbles in the data where populations are very low, for example Mississippi, where the census recorded two very sparsely-populated counties having more slaveholders than families (possible, but unlikely), or on the Texas frontier, where the data maps the finding that almost every family probably included a slaveholder. But in spite of its imperfections, it nonetheless presents a picture that more accurately describes the presence of slaveholding in the everyday lives – indeed, under the same roof – of citizens of the Confederate States than the much smaller number of slave owners does.

Aaron Perry, whose seven slaves are enumerated above in an excerpt from the 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedule, illustrates the point. Perry, a Texas State Representative who raised hogs and corn in Limestone County (east of present-day Waco) had two sons, William and Mark (or Marcus), living with him at the farm at the time of the census. The elder Perry owned $3,000 worth of land, and nearly four times that in personal property, most of which must have been represented in those seven slaves. When the war came, both sons joined the Eighth Texas Cavalry, the famed Terry’s Rangers. Because neither of the sons – aged 21 and 17 respectively at the time of the census – held formal, legal title to a bondsman, Confederate apologists would claim that they are among the “ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers [that] never owned a slave,” and, by implication, therefore had no interest or motivation to protect the “peculiar institution.” Nonetheless, it was slave labor that made their father’s farm (and their inheritance) a going concern. It was slave labor that, in one way or another, provided the food they ate, the shelter over their heads, the money in their pockets, the clothes they wore, and formed the basis of wealth they would inherit someday. And when they went to war, it was slave labor that made it possible for them to bring with them the mounts and sidearms that Texas cavalrymen were expected to provide for themselves. While the Perry boys left no record of their personal thoughts or motivations upon enlisting, the notion that these two young men must have had no interest, no personal stake, in the preservation of slavery as an institution is simply asinine on its face.

You don’t have to talk to a Confederate apologist long before you’ll be told that only a tiny fraction of butternuts owned slaves. (This is usually followed immediately by an assertion that the speaker’s own Confederate ancestors never owned slaves, either.) The number ascribed to Confederate soldiers as a whole varies—two percent, five percent—but the message is always the same, that those men 150 years had nothing to do with the peculiar institution, they had no stake in it, and that it certainly played no role whatever in their personal motivations or in the Confederacy’s goals in the war. But such a blanket disassociation between Confederate soldiers and the “peculiar institution” is simply not true in any meaningful way. Slave labor was as much a part of life in the antebellum South as heat in the summer and hog-killing time in the late fall. Southerners who didn’t own slaves could not but avoid coming in regular, frequent contact with the institution. They hired out others’ slaves for temporary work. They did business with slaveholders, bought from or sold to them. They utilized the products of others’ slaves’ labor. They traveled roads and lived behind levees built by slaves. Southerners across the Confederacy, from Texas to Florida to Virginia, civilian and soldier alike, were awash in the institution of slavery. They were up to their necks in it. They swam in it, and no amount of willful denial can change that.

Coming up: Did non-slaveholding Southerners have a stake in fighting to defend the “peculiar institution?”

_____________________

Images: Top, list of seven slaves belonging to Texas State Representative Aaron Perry of Limestone County, Texas, from the 1860 U.S. Census slave schedules, via Ancestry. Below, central image on the face of a Confederate States of America $100 note,issued at Richmond in 1862, featuring African Americans working in the field, via The Daily Omnivore Blog.

This post is adapted from one originally appearing in The Atlantic online in August 2010.

Not Surprising

Over at Civil War Emancipation, Donald R. Shaffer highlights a table by David C. Hanson of Virginia Western Community College, that compares slaveholding states’ date of secession with their populations of slaves and slaveholders as recorded in the 1860 U.S. Census. Shaffer notes that “David C. Hanson makes a definite connection between the concentration of slaves and slaveholders in a particular southern states and when it seceded from the Union in 1860-61, and whether it seceded at all. Certainly, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence connecting slavery and Civil War causation, but this table also makes a compelling statistical case.”

No shit. It turns out that for the eleven states that actually seceded, the proportion of free persons owning slaves was an excellent predictor of the order in which they seceded, beginning with South Carolina. I plugged the numbers into Excel and found that the percentage of slaves as part of the state’s overall population was equally reliable as a predictor. Assigning each state a number corresponding to its order of secession (South Carolina = 1, Mississippi = 2, etc.), the correlation coefficient for both the percentage of slaveholders among the free population, and for the proportion of slave among the overall population, was in both cases beyond -0.9. In short, each percentage is a nearly perfect predictor of where each state falls in the order of secession. The states with the largest proportions of slaves and slave-holders seceded earliest.

_____________

64 comments