The NYT Visits the Museum of the Confederacy

On of my readers, PH, passes along this recent review in the New York Times of the Museum of the Confederacy, and its ongoing effort to chart a new course, away from its founding as a shrine to the Lost Cause, to a more comprehensive, balanced view of the conflict, its origins and its legacy. (Kevin has blogged on it as well.) Edward Rothstein makes a second visit to the MoC, and notes the shifting tenor of the institution’s public exhibitions and programs.

The Museum of the Confederacy embodies the conflict in its very origins; its artifacts were accumulated in the midst of grief. The museum’s first solicitation for donations, in 1892, four years before its opening, is telling: “The glory, the hardships, the heroism of the war were a noble heritage for our children. To keep green such memories and to commemorate such virtues, it is our purpose to gather together and preserve in the Executive Mansion of the Confederacy the sacred relics of those glorious days. We appeal to our sisters throughout the South to help us secure these invaluable mementoes before it’s too late.”

That heritage casts a long shadow over the institution. When I visited in 2008, slavery still seemed an inconsequential part of Southern history. And Southern suffering loomed large.

But changes have been taking place. Several tendentious text panels (in one, Lincoln was portrayed as having manipulated the South into starting the war) have been removed. And gradually, under the presidency of S. Waite Rawls III, the museum, while keeping its name, has been expanding its ambitions, trying to turn its specialization into a strength instead of a burden.

Nonetheless, Rothstein comes away feeling that, while the worst examples of the MoC’s old historical narrative are gone, there’s nothing yet that has taken their place:

The delicacy is strange. There is so much in the exhibition [“The War Comes Home”] that is illuminating about the war. And it isn’t that the Virginia Historical Society is embracing the Lost Cause. Far from it. But the institution is trying to take a path that will least offend those who do. Or is it suggesting with its questions that it would be callous to continue with finger pointing? After all, isn’t one man’s traitor another’s patriot?

The problem, though, is that the Civil War then becomes merely a tragic clash of two sides, each convinced of its virtue and fidelity to national ideals. That is not an embrace of the Lost Cause, but it leaves us a war with no higher cause at all.

Rothstein should be patient, I think. Museums are not shrines; they exist for education and research, and unquestioning hagiography is best left to others. The MoC in particular, with its unsurpassed collection of Civil War artifacts, documents, and images, is far too valuable a resource to give itself over to a fixed story of parochial, navel-gazing victimhood. Like every institution of its type, the Museum of the Confederacy is, and should be, always a work in progress.

______________

Image: “Museum of the Confederacy CEO Waite Rawls announced on Thursday [April 14, 2011] the museum’s plans for interior exhibits. Part of the plan includes bringing the uniform won by Gen. Robert E. Lee, of the Army of Northern Virginia, at the Appomattox surrender in April of 1865 (pictured at left). Also included will be the sword Lee brought to the surrender.” Via Lynchburg, Virginia News & Advance.

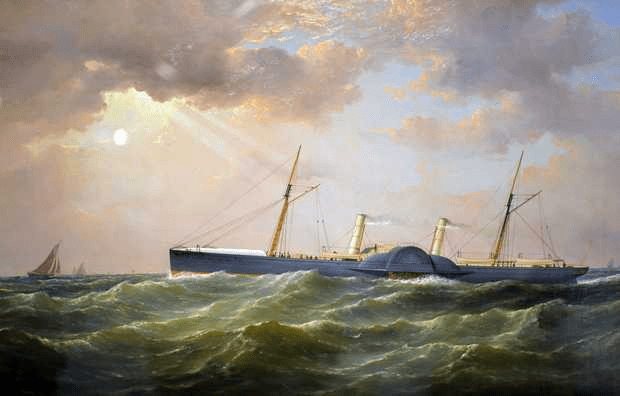

Talkin’ Blockade Runners

I gave a talk Thursday evening at the Brazoria County Historical Museum in Angleton. I hadn’t presented on that subject in a long time, but it seemed to go reasonably well. The audience was small but engaged, with a good many questions during and after the presentation. I always think of that as a good sign. I focused primarily on the vessels I know best, Denbigh and Will o’ the Wisp. The third large steam runner wrecked near here, Acadia, is the subject of an exhibit at the museum, which houses many of the artifacts recovered from the site in the late 1960s/early 1970s.

A last-minute addition to the program was Flem Rogers, a specialist in Civil War era weapons, who brought with him several arms loaned for the evening by private collectors. All were produced in the UK and imported through the blockade. It was a great way to close the evening, with some hands-on lessons that really brought home the practical issues involved in arming Confederate forces.

I’d like to extend my thanks to Michael Bailey and Herb Boykin, of the museum, who did so much to make my visit there a pleasant and successful one. The museum has a fantastic collection — and, I will point out, a very well-organized collection storage facility, often a problematic-but-hidden aspect of local history museums — and I hope to get back down there to do some follow-up research soon.

____________

Image: ‘PS Banshee‘ by Samuel Walters, Accession number 1968.5.2, National Museums, Liverpool. This ship, the second of two Banshees that ran the blockade, made a famous daylight dash through the Federal blockade into Galveston on the morning of February 24, 1865.

U.S.S. Monitor Turret Revealed

Via Michael Lynch at Past in the Present, there are about three weeks left to see the 120-ton turret of the Union ironclad Monitor, currently undergoing restoration at the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News.The turret, recovered from the sea floor off Cape Hatteras in 2002, has been kept in a flooded tank of fresh water almost the entire time since then, allowing the salts that have penetrated the iron to gradually leach out. After a thorough cleaning, the turret will be flooded again, to to continue desalinization, a lengthy process that may take up to 15 more years. Even with the tank drained, it’s slow, painstaking work:

[Gary] Paden is an objects handler working in the USS Monitor Center at The Mariners’ Museum. He was gently nudging, hour after painstaking hour, a wrought-iron stanchion from the 9-foot-tall revolving gun turret that once sat atop the Civil War ironclad.

The stanchions rimmed the roof of the Monitor and held up a canvas awning to shelter the crew from the broiling sun. The stanchions needed to be removed so they could be separately treated for conservation.

Last week Paden strived to remove one of those stanchions from its bracket using a hydraulic jack. “I spent seven hours on it yesterday,” Paden said. “So far it’s been the most difficult one.”

Several other workers came in closer to watch, including Dave Krop, manager of the Monitor conservation project.

Paden said most of the tools used in restoring the various components of the Monitor brought up from the ocean’s floor were improvised. The hydraulic jack is an auto body tool used to fix dents.

He pressed the jack into the point where the stanchion met the bracket. A moment later, the stanchion fell from its 149-year-old position.

“Wow,” Krop said. “You got it off. Pretty awesome! That’s pretty awesome!”

Several handlers nearby paused from their snail’s-pace labors to savor the moment, beaming in Paden’s direction.

A few years ago I visited Mariners while doing research on another vessel and, after talking to one of the conservators there about my own project, was offered the chance to take a brief tour of the lab where they were working on Monitor artifacts. (That says less about me than it does about how much they wanted to show off the work they were doing there, and rightly so.) I wasn’t allowed to take pictures, but they showed me a first a life-sized color photograph of an encrusted dial from the engine room — a steam gauge, I think — and then, with a well-practiced flourish, pulled back a cloth covering the same artifact, now almost pristine, looking as new as the day the ship sailed over 140 years before. Folks like Gary Paden and Dave Krop don’t get a lot of attention, because their work is all behind-the-scenes, but it’s important to recognize what they do, that benefits every history buff and museum-goer.

Moment of nerd: the dents made to the exterior of Monitor‘s turret by the guns of C.S.S. Virginia are still visible, 149 years later, on the interior of the upside-down turret. Additional damage to the deck edge is visible at lower right.

More video via the New York Times here. The tank containing Monitor‘s turret will be drained during the week during the rest of August. I hope some of y’all can make the trip. I’m certain you won’t be disappointed. For the rest of us, there’s always the webcam.

Added: Three additional images showing the interior of the turret, all from Miller’s book (top to bottom): Contemporary illustration from Harper’s Weekly; original drawing from Ericsson’s plan; and a modern cutaway illustration by the great Alan B. Chesley.

_________

Top color photo: “Dave Krop, who manages the Monitor conservation project, works inside the inverted turret at the Mariner’s Museum. Visitors can watch the work from viewing platforms or online.” Credit: Steve Earley, the Virginian-Pilot. Archival photo: Library of Congress. Bottom photo: Diorama of interior of Monitor‘s turret in action by Sheperd Paine, from U.S.S. Monitor: The Ship that Launched a Modern Navy by Lt. Edward M. Miller, USN.

Soldiers All

Recently I’ve gotten the sense that, among those who are pushing broad, generalized assertions about the involvement of African Americans in the Confederate war effort, there’s been a notable tendency to back off the specific claim that they were recognized as soldiers at the time, opting instead for much more vague terms like “black Southern loyalist” that, having no clear objective standard to begin with, can also neither be directly refuted. Such language is warm and fuzzy, but has the great advantage that it can be applied to almost anyone, based on almost anything. It also tells us as much about the speaker as it does about the subject.

Nonetheless, one of the more prominent advocates on the subject of BCS continues to twist herself in rhetorical knots to demonstrate retroactively that African American cooks, body servants, teamsters and so forth should actually be considered Confederate soldiers, regardless of how they were viewed at the time. She recently proposed definitions of “Black Confederate” and “Black Confederate Soldier:”

A “Black Confederate” is an African-American who is acknowledged as serving with the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

A “Black Confederate Soldier” is (1) an enlisted African-American in the Confederate States Army, (2) an African-American acknowledged by Confederate Officer(s) as engaged in military service, and/or (3) an African-American approved by the Confederate Board of Pension Examiners to receive a Confederate Pension for military service during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

There are multiple problems with these definitions. The first is that there’s no practical difference between “acknowledged as serving with the Confederate States Army” (Definition 1) and “acknowledged by Confederate Officer(s) as engaged in military service” (Definition 2). A Venn diagram of these would be an almost perfect circle. In this suggested scheme, “Black Confederate” and “Black Confederate Soldier” are entirely equivalent. Anyone should be able to see that, even without knowing anything more about the subject.

Second, she defines a soldier as anyone acknowledged “as having engaged in military service,” which falls back on the never-defined, all-encompassing word “service.” This is a common technique — see the discussion thread here — which sounds simple enough, but conflates a whole range of activities that, at the time, fell into clearly-defined realms.

Third, she’s still hopelessly muddled on the subject of pensions — who awarded them, and what they were awarded for, and what classes of pensions were awarded. Some states awarded pensions explicitly for former slaves/servants (e.g., Mississippi), while others did not. There was no single, central body called the “Confederate Board of Pension Examiners;” pension programs were set up by individual states, each with their own rules and procedures. Individual applications were usually reviewed and endorsed by local boards, which introduces all sorts of unknown variables in procedure and documentation. In at least some cases, the state verified applicants’ service records with the War Department — these materials were later transferred to the National Archives — and even this verification process appears to have resulted in at least one error of mis-identification. The famous Holt Collier, who probably comes as close as anyone to having actually been a Confederate combatant in practice, received three pension awards from Mississippi in his old age — first as a personal body servant, then as a soldier, then again as a servant. In short, pension records tell us very little about the applicants’ status forty, fifty, sixty years before. (The basic primer to understanding the process for awarding Confederate pensions — and their limitations — remains James G. Hollandsworth, Jr.’s manuscript, “Looking for Bob: Black Confederate Pensioners After the Civil War,” in the Journal of Mississippi History.)

This particular researcher has a long track record of glossing over distinctions between slaves and free African Americans, personal servants, cooks, and enlisted soldiers under arms. In the interest of reconciliation and reunion, she consistently rejects the hard realities of race, law and society in the mid-19th century, and insists that all Confederates, writ broad, saw themselves as standing on an equal footing. In an effort to draw an equivalency between African American men employed as cook in the Confederate army with those in the Union, she latches onto a single, three-word notation in the record of one Private Lott Allen of the 21st USCT :

On the left, Lot Allen enlisted with the Union Army 21st United States Colored Troops (USCT) Company A as an “on order cook.” [sic., “in duty cook”] On the right, William Dove enlisted with the Confederate States Army North Carolina 5th Cavalry Company D as a “cook.” Both men contribute to United States Military history; and their soldier service records are each recorded in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

Her statement about Private Allen is factually incorrect; as his compiled service record from NARA (14MB PDF) makes clear, Lott Allen enlisted as a U.S. soldier and, being 42 years old, was immediately assigned to work as a cook because he couldn’t keep up as an infantryman. His disability discharge from June 1865 says so explicitly: “Since his enlistment to the present date he has been Company Cook and is too old a man to perform the duty of a soldier.” The regimental surgeon, John M. Hawks, goes on to explain that Allen is unable to perform the duties of a soldier because of “old age; its consequent disability and infirmities. He has never been able to drill, or to march with the company, or do any military or fatigue duty; and he is too careless and slovenly for a cook.” Private Lott Allen didn’t enlist as a cook; he enlisted as a soldier, couldn’t cut it, and (it seems) wasn’t very good as a cook, either.

Posting elsewhere, the researcher takes her assumption about Private Allen and spins it off into a grand, sweeping claim encompassing thousands or tens of thousands of others:

The question is: Were there cooks, teamsters, laborers in the Union Army United States Colored Troops? The answer is yes. As an example in the image of this post, Private Allen Lot [sic.], a soldier with the Union Army 21st United States Colored Troops, served as an “On [sic.] Duty Cook.” See Private Allen Lot’s Union Soldier Service Record (NARA Catalog ID 300398).

Therefore, with this preponderance of the evidence, African-Americans on Confederate Soldier Service Records (muster rolls) who are listed as cooks, teamsters, laborers, etc. should likewise be called soldiers. The sun rises and it shines on us all.

She takes a single notation that this man was assigned as a cook and then extrapolates that to argue that all “who are listed as cooks, teamsters, laborers, etc. should likewise be called soldiers.” She makes what is formally known as a “converse accident,” but is a simple and obvious logical fallacy: she reasons that this soldier was a cook; therefore all cooks were soldiers. (And teamsters, and laborers. . . .)

It’s hard to know whether this researcher bothered to look at all of Allen’s CSR or just didn’t understand it, but it really doesn’t matter. Either way she misrepresents Allen’s actual situation, and then uses that flawed example to make a sweeping rhetorical argument applied to tens of thousands of men in an entirely different army.

This is, sadly, typical of most of the “research” that goes into BCS advocacy; it’s a mile wide and a half-inch deep. It’s pulling out a word here, a line there, and announcing it as “proof” with little consideration of the full record, even when, as in this case, it’s readily available. It’s about adding names to a list, with little or no real understanding of the larger story, or the historical context of the claim being made. It’s just unbelievably superficial.

There’s no question that tens of thousands of African Americans went into the field with the Confederate army as cooks, personal servants, teamsters, laborers, and so on. Some were free; most were slaves. Some undoubtedly went willingly, but far more went with with some degree of coercion (legal, economic, physical) guiding their steps. Some saw combat, even though very, very few were officially in a combat role. There is a tremendous, untapped resource there for serious research. But they were not formally considered soldiers at the time, by either the Confederate or Union army. Robert E. Lee didn’t recognize these men as soldiers; he thought such pretensions made a fine joke. Howell Cobb didn’t recognize these men as soldiers. Kirby Smith didn’t see these men as soldiers. So why do some people today, like this researcher, devote so much effort to retroactively designate them so? Why is “proving” that point so much more important than telling their actual stories as individuals? Sure, this researcher finds Lott Allen and William Dove useful for making an analogy, but does she offer any additional information about them? (Hint: if you’ve read this far, you already know more about Lott Allen than you’re ever likely to find on the researcher’s site.)

I regret feeling obligated to make this post at all, and have no doubt it will be framed as a personal attack on this particular researcher’s character. It’s not; I’ve repeatedly said before, and still believe, that she is sincere and well-intentioned in her efforts. But it’s also clear that she doesn’t understand the materials she’s working with, and has no sense of her own limitations in that regard. But she is viewed as a among BCS advocates as a leading researcher on the subject, and maintains an extensive website dedicated to it. If she is to be respected and valued as a researcher, she needs to be subject to the same fact-checking on her research and methodology that the rest of us are; she doesn’t get a pass because she’s not professionally trained, or because she’s well-intentioned.

There’s a saying, much quoted by True Southrons™, that “history is written by the winners.” This reflects their sincere belief that their own preferred historical narrative is somehow suppressed by professional historians and censored in academic curricula. That’s wrong; history is history, regardless of who writes it. But the work they do needs to stand up to scrutiny, and most of it just doesn’t.

_______________

Too Many Historians, Too Little Time

Blog reader dmf alerted me this morning to today’s Diane Rehm Show on NPR, that devoted an hour to the subject of The Civil War: America’s 2nd Revolution, with particular emphasis on the coming of the war and the way it’s perceived today. I don’t usually have a chance to listen to Rehm’s show, but the panel today was A-List: Adam Goodheart, author of 1861: The Civil War Awakening; David Blight, author of Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, the upcoming American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era, and a popular undergrad lecture series available online; Thavolia Glymph, author of Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household; and Chandra Manning, author of What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War.

Blog reader dmf alerted me this morning to today’s Diane Rehm Show on NPR, that devoted an hour to the subject of The Civil War: America’s 2nd Revolution, with particular emphasis on the coming of the war and the way it’s perceived today. I don’t usually have a chance to listen to Rehm’s show, but the panel today was A-List: Adam Goodheart, author of 1861: The Civil War Awakening; David Blight, author of Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, the upcoming American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era, and a popular undergrad lecture series available online; Thavolia Glymph, author of Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household; and Chandra Manning, author of What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War.

They covered a lot of ground, and easily could have gone on for another hour. I’ll have more to say when the episode’s transcript is posted, but for now you can listen online.

Update: Transcript here.

____________

On the Road

There are lots of good things about living where I do, but one you won’t find in the Chamber of Commerce brochures is that there are four wrecks of Civil War steam blockade runners right along this stretch of the Upper Texas Coast. Two of them, Acadia and Denbigh, have been positively identified; a third, Will o’ the Wisp (above), has been tentatively identified, and a fourth, Caroline (or Carolina) may have been located. Good, good stuff.

I’ve had the opportunity to dive on a couple of these sites, and from 1997-2003 was one of the lead investigators on Denbigh, the only one of the four to be formally excavated as an archaeology project. Denbigh was a remarkable ship, built in the same Birkenhead yard as the Confederate raider Alabama — which has its own connection to Galveston, thankyouverymuch — the second-most-successful runner of the war, having completed a total of eleven round voyages between Havana and Mobile, and Havana and Galveston, before being lost on the inbound passage of her twelfth trip into the Confederacy in May 1865.

But I digress. I’ve accepted an invitation to speak on Civil War blockade runners on the Texas coast on Thursday, October 20 at the Brazoria County Historical Museum in Angleton as part of Texas Archaeology Month. It’s been a long time since I talked about blockade runners, so it will be nice to return to that subject. More details closer to the date.

More blockade runner aye candy here.

_____________

Frankly, my dear. . . .

The scene, driving into school Friday:

[Kid digs around for loose change in the console]

Me: What are you looking for?

Kid: I need 75 cents for popcorn.

Me: Popcorn?

Kid: Yeah, Ms. _____ lets us get popcorn, we’re watching a movie in her history class.

Me: What movie?

Kid: Gone with the Wind. It’s awful, and we all get popcorn ’cause it’s sooooo booooring.

Turns out they’d spent the entire week, since Monday, watching Gone with the Wind in class. The good news, I suppose, is that (according to the Kid) none of it registers with the the other middle school students. They’re not following the plot, they can’t keep the characters straight, and the dialogue is mostly incomprehensible. They’re distracted that one of the leading male characters “has a girl’s name.” The clothing looks ridiculous. They have only the vaguest sense of the course of the war, which is the mostly-off-screen event that drives the entire plot of the picture. Interaction between characters like the one pictured above just don’t register. Gone with the Wind, it seems, is a waste in the classroom when presented in this way; it might as well be a Bollywood musical, with all the dialogue and lyrics in Hindi, for all the effect it’s having. The only thing it’s teaching this class is to remember to bring their three quarters every day for popcorn. (Kevin, teaching at the high school level, has used segments from GwtW, but that’s an entirely different approach to classroom use of the film.)

There’s no question that Gone with the Wind is one of the classic films of all time. And it should be remembered in that context. But it’s portrayal of the Antebellum South and its depiction of slavery is atrocious, Hattie McDaniel’s Oscar notwithstanding. It’s not a history lesson.

I feel like I know Ms. _____ reasonably well, and I’m surprised, to say the least. No idea what’s going on here, or why GwtW would be the film of choice, even if one does choose to coast the rest of the year. (State-mandated standardized testing, which seems to be the tail that wags the dog, wrapped up last week.) There are much better, more historically accurate films out there, although they may not be do-able for the classroom. Glory, for example, is rated R; although the violence in it is probably not more gruesome than what’s seen on prime-time broadcast teevee, an R-rated film is a non-starter in the classroom. Gettysburg came out just four years later, and it’s only PG.

What’s done is done for this year, but I think I’ll drop a note to Ms. _____. I really hate to be one of those parents who’s always getting up in the teacher’s face, and the plain truth of the matter is that we’ve rarely had reason to complain. But there’s got to be something better than this.

__________________

On the Block

On Saturday, a group in St. Louis, Missouri re-enacted an antebellum slave auction on the steps of the city’s old courthouse. There are more photos here, and a news story about the planned event from KSDK Channel 5. From Channel 5:

Angela deSilva takes her history seriously — as an adjunct professor of American Studies and as a Civil War era re-enactor of American slave history, based on a knowledge that began with stories from her grandmother.

“I can remember being very, very young and listening to her talk about her grandmother who had been a slave,” says deSilva. “And I remember asking her what a slave was.”

A frequent slave re-enactor at the Daniel Boone Home, deSilva is bringing her history lesson to the steps of the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis Saturday, staging a mock slave auction with the help of dozens of historical re-enactors from across the region. DeSilva says it the 150th anniversary of the Civil War this year that prompted her to recreate such a dark scene in St. Louis history.

“You need to remember that there was another aspect to this. That a whole race of people was freed as a result there of,” she says of America’s deadliest war.

The National Parks Service oversees the Old Courthouse and as far as anyone there knows this will be the first event of its kind since the real thing back in the 1860’s. And organizers are aware it will be disturbing for some.

“It’s not that it’s glorifying it,” says deSilva defending the idea. “Not at all. I have relatives that could have been sold on those very steps.”

“When you talk about the Holocaust everyone says, ‘don’t forget us, never let them forget.’ But sometimes in slavery we want to bury it. I personally, I can’t do it. I cannot do it. I guess because the slaves in my past have names.”

This is a bold effort that pushes back — hard — against so much of what’s being done in the way of reenactments as part of the Civil War Sesquicentennial, such as the SCV-sponsored reenactment of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis next week. The “auction” held today in St. Louis is itself a deeply controversial event, even among African American groups, and that’s to be expected. It recalls a demeaning and ugly part of our shared history, and it’s something that a great many people would simply like to relegate to books and museum exhibits. St. Louis is a particularly important place to recognize this aspect of antebellum history, as it was one of the main centers of the domestic slave trade, with dealers buying and selling wholesale, in enormous quantities (left, advertisements in the Daily Missouri Republican, December 18, 1853).

This is a bold effort that pushes back — hard — against so much of what’s being done in the way of reenactments as part of the Civil War Sesquicentennial, such as the SCV-sponsored reenactment of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis next week. The “auction” held today in St. Louis is itself a deeply controversial event, even among African American groups, and that’s to be expected. It recalls a demeaning and ugly part of our shared history, and it’s something that a great many people would simply like to relegate to books and museum exhibits. St. Louis is a particularly important place to recognize this aspect of antebellum history, as it was one of the main centers of the domestic slave trade, with dealers buying and selling wholesale, in enormous quantities (left, advertisements in the Daily Missouri Republican, December 18, 1853).

I’m really undecided about reenactments in general as a means of teaching history and, more than a conventional battle reenactment, this event in particular is fraught with opportunity for misinterpretation and misunderstanding. I just don’t know how well it works. But if it keeps the conversation going about the underlying issues of the war, how we interpret the conflict, and the myriad of perspectives involved, then that’s all to the good.

Update: Kevin has a long and thoughtful post on this event here; Bob Pollock has photos and comments here. And Abbi Telander has more reflections on it here:

This is part of our shared heritage. Whether or not your descendants [sic.] were involved does not negate the fact that we all share this history as Americans. We share the agonies of the enslaved as well as the fight of the abolitionist and the responsibility of the owners. We have a responsibility to our past to understand it and a responsibility to our future to do better. Our nation, forged under the debate over the rights of man, went to war in an attempt to determine whether we could be one country with this shared past. Our nation has been fighting ever since over who was right and who was wrong, who deserves the glory and who deserves the blame, who deserves the benefits of citizenship, and who needs to be remembered in the annals of history.

I dare anyone who stood in the cold this morning and watched as the story of buying and selling other people unfolded to say that our sins need to be forgotten. I dare anyone present to forget this day. As my baby kicked inside me, innocent and pure, I promised her that I would someday tell her what she couldn’t see today, and that she would know why it was important that she know, and why I cried when those little girls stood up to be sold.

_____________________________

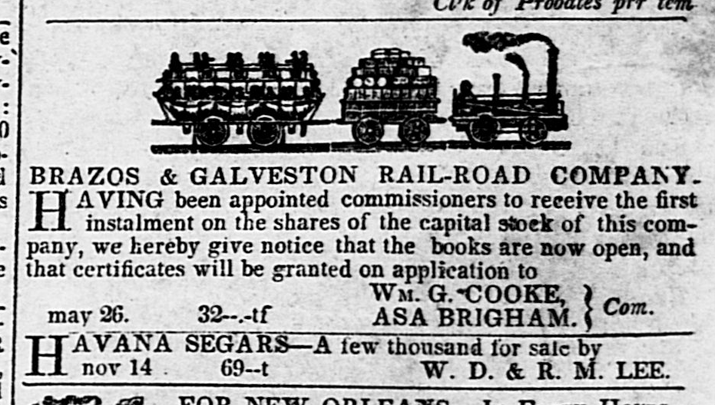

“Havana segars — a few thousand for sale”

The Portal to Texas History now has copies of the Houston Telegraph and Texas Register available online, with full word-search capabilities. The Telegraph was the first newspaper to gain real prominence in the Texas Republic, and this addition offers researchers a great window into that period, previously available only through microfilm. The online collection for this particular paper covers the period from 1835 to 1846.

The extension of traditional archival materials into publicly-accessible, digital format is tremendously exciting, and makes research possible for many folks who otherwise face obstacles that make conventional research a challenge of both timing and logistics. In my case, looking up something in the Telegraph meant devoting a Saturday to microfilm at the Metropolitan Research Center at the Houston Public Library — often rewarding, but nonetheless a headache. The appearance of easily-accessed, online sources from both non-profits like Portal to Texas History and Open Library commercial vendors like Footnote and NewspaperArchive.com really are changing the face of research.

Great stuff.

____________________________

Image: Advertisements from the Telegraph and Texas Register, January 16, 1839.

The Grand Review in Harrisburg

Commenter David Cassatt points out that this coming weekend in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania is the Grand Review, a celebration of the service of USCT during the Civil War. The program of scheduled activities is lengthy (PDF), with something for everyone. The Grand Review commemorates the November 1865 event of the same name organized by the women of Harrisburg to honor the United States Colored Troops from 25 states who were not permitted to participate in the Grand Review of the Armies, a military procession and celebration held May 23-24, 1865 in Washington, D.C., following the end of the Civil War.

This looks like a great event. Sorry for the short notice. Additional information here.

2 comments