What Does Hannibal Alexander Tell Us About Black Confederate PoWs?

One of the things that’s often offered as evidence of African Americans serving as Confederate soldiers is the fact that some of these men were captured and held in Northern prison camps. Why would these men be held if they were not soldiers? goes the thinking, and there are PoW records that show them as soldiers. It’s a compelling rhetorical argument, but reality is oftentimes more complex than that. From the Confederate Veteran, January 1901:

Hannibal Alexander was a slave belonging to Parker Alexander. He went with his young master, Sidney Alexander, to the war, and did his duty faithfully. “Ham” died recently in Monroe County, Miss. He and his wife Delia by industry made a good living and accumulated a competence, ever having the confidence and friendship of the white people about their lifetime home. Writes W. A. Campbell, of Columbus :

In the army he was cook. He was in the siege of Fort Donelson. He was captured there, and went to Camp Douglass [sic.] as a Confederate prisoner. He answered roll call all the time as a white soldier. Being a bright [i.e., light-skinned] mulatto, he was brought to Vicksburg and exchanged with the others, and again went with his young master into service.

The Federal sergeant that called the roll was somewhat suspicious as to “Ham” (as he was called by the boys) being a slave, but he was told that living in Mississippi he was sunburned and that made him dark.

Hannibal was a very intelligent negro [sic.], and knew if he left his master he could go free, but he elected to stay with him among the white men he had been raised with, and preferred to suffer with them.

I knew Hannibal for more than forty years as slave and freeman, and he was ever polite and friendly to all his former owners. In the old days I went on many a hunting and fishing expedition with Sidney, with “Ham” to wait on us.

His old master with whom he went in the army is yet alive, but in poor health.

There are a number of examples of mixed-race men “passing” to enter Confederate military service, only to be discharged when found out; Alexander’s is a case of “passing” to remain with his master inside the confines of Camp Douglas.

There are a number of examples of mixed-race men “passing” to enter Confederate military service, only to be discharged when found out; Alexander’s is a case of “passing” to remain with his master inside the confines of Camp Douglas.

There’s a lot to digest in Hannibal Alexander’s story. The Confederate Veteran story is framed, typically, as that of a slave’s lifelong fidelity to his master, and willingness to suffer the (very real) hardships of a Federal prison camp to do so. (This short piece is part of a section called, “Faithful Negroes Who Were Slaves.”) But it’s important to recognize that this story makes it clear that in remaining in the camp, Alexander consciously chose to represent himself as a white soldier, rather than his actual status as an enslaved cook. The article also argues that his decision to remain was one of personal loyalty to his master, not to the regiment or the Confederacy. As others have often pointed out, it’s not sufficient just to say a man “served” when talking about slaves and the Confederate army; it’s important to make a distinction about who or what he was in service to.

And of course, we have nothing at all from Alexander himself to explain his decision.

Alexander’s story is revealing because a number of “black Confederate solders” have been so identified on the basis of documents just like Alexander’s compiled service record (CSR, right) that record their presence in Union prison camps. Based on his assumed identity, Alexander’s card identifies him as a private in the 20th Mississippi Infantry, a rank he never actually held. Significantly, too, there are only two items in Alexander’s CSR folder, both relating to his parole, and originating from Camp Douglas (“roll dated Headquarters Camp Douglas, Chicago, Ill.”). There’s no Confederate record for him, dating from before or after Camp Douglas, because he wasn’t considered a soldier. By comparison, the CSR for the master he served, Sidney Alexander, contains nine separate cards detailing his career as a private in Co. B of that regiment.

Hannibal Alexander’s case is an intriguing one for a number of reasons. How valuable would it be to have Alexander’s own, unvarnished account of these events, rather than as told through the eyes of his former master’s old friend? It would be useful to know how many African American cooks and servants found themselves, like Hannibal Alexander, swept up by the Union army and made the decision to remain in the camp, passing themselves off as enlisted soldiers to do so. It’s also a good object lesson in how there might be a CSR in the National Archives for a man who was never actually recognized as a soldier by the Confederacy.

Oh, one other thing — the Confederate Veteran piece says that Sidney Alexander returned to military service, but his CSR notes that in March 1863, six months after his parole from Camp Douglas, Sidney received a discharge after hiring a substitute. Rich man’s war, poor man’s fight, y’all.

___________

Image: Camp Douglas, Chicago, c. 1863. Chicago Historical Society.

Soldiers All

Recently I’ve gotten the sense that, among those who are pushing broad, generalized assertions about the involvement of African Americans in the Confederate war effort, there’s been a notable tendency to back off the specific claim that they were recognized as soldiers at the time, opting instead for much more vague terms like “black Southern loyalist” that, having no clear objective standard to begin with, can also neither be directly refuted. Such language is warm and fuzzy, but has the great advantage that it can be applied to almost anyone, based on almost anything. It also tells us as much about the speaker as it does about the subject.

Nonetheless, one of the more prominent advocates on the subject of BCS continues to twist herself in rhetorical knots to demonstrate retroactively that African American cooks, body servants, teamsters and so forth should actually be considered Confederate soldiers, regardless of how they were viewed at the time. She recently proposed definitions of “Black Confederate” and “Black Confederate Soldier:”

A “Black Confederate” is an African-American who is acknowledged as serving with the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

A “Black Confederate Soldier” is (1) an enlisted African-American in the Confederate States Army, (2) an African-American acknowledged by Confederate Officer(s) as engaged in military service, and/or (3) an African-American approved by the Confederate Board of Pension Examiners to receive a Confederate Pension for military service during the American Civil War (1861-1865).

There are multiple problems with these definitions. The first is that there’s no practical difference between “acknowledged as serving with the Confederate States Army” (Definition 1) and “acknowledged by Confederate Officer(s) as engaged in military service” (Definition 2). A Venn diagram of these would be an almost perfect circle. In this suggested scheme, “Black Confederate” and “Black Confederate Soldier” are entirely equivalent. Anyone should be able to see that, even without knowing anything more about the subject.

Second, she defines a soldier as anyone acknowledged “as having engaged in military service,” which falls back on the never-defined, all-encompassing word “service.” This is a common technique — see the discussion thread here — which sounds simple enough, but conflates a whole range of activities that, at the time, fell into clearly-defined realms.

Third, she’s still hopelessly muddled on the subject of pensions — who awarded them, and what they were awarded for, and what classes of pensions were awarded. Some states awarded pensions explicitly for former slaves/servants (e.g., Mississippi), while others did not. There was no single, central body called the “Confederate Board of Pension Examiners;” pension programs were set up by individual states, each with their own rules and procedures. Individual applications were usually reviewed and endorsed by local boards, which introduces all sorts of unknown variables in procedure and documentation. In at least some cases, the state verified applicants’ service records with the War Department — these materials were later transferred to the National Archives — and even this verification process appears to have resulted in at least one error of mis-identification. The famous Holt Collier, who probably comes as close as anyone to having actually been a Confederate combatant in practice, received three pension awards from Mississippi in his old age — first as a personal body servant, then as a soldier, then again as a servant. In short, pension records tell us very little about the applicants’ status forty, fifty, sixty years before. (The basic primer to understanding the process for awarding Confederate pensions — and their limitations — remains James G. Hollandsworth, Jr.’s manuscript, “Looking for Bob: Black Confederate Pensioners After the Civil War,” in the Journal of Mississippi History.)

This particular researcher has a long track record of glossing over distinctions between slaves and free African Americans, personal servants, cooks, and enlisted soldiers under arms. In the interest of reconciliation and reunion, she consistently rejects the hard realities of race, law and society in the mid-19th century, and insists that all Confederates, writ broad, saw themselves as standing on an equal footing. In an effort to draw an equivalency between African American men employed as cook in the Confederate army with those in the Union, she latches onto a single, three-word notation in the record of one Private Lott Allen of the 21st USCT :

On the left, Lot Allen enlisted with the Union Army 21st United States Colored Troops (USCT) Company A as an “on order cook.” [sic., “in duty cook”] On the right, William Dove enlisted with the Confederate States Army North Carolina 5th Cavalry Company D as a “cook.” Both men contribute to United States Military history; and their soldier service records are each recorded in the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

Her statement about Private Allen is factually incorrect; as his compiled service record from NARA (14MB PDF) makes clear, Lott Allen enlisted as a U.S. soldier and, being 42 years old, was immediately assigned to work as a cook because he couldn’t keep up as an infantryman. His disability discharge from June 1865 says so explicitly: “Since his enlistment to the present date he has been Company Cook and is too old a man to perform the duty of a soldier.” The regimental surgeon, John M. Hawks, goes on to explain that Allen is unable to perform the duties of a soldier because of “old age; its consequent disability and infirmities. He has never been able to drill, or to march with the company, or do any military or fatigue duty; and he is too careless and slovenly for a cook.” Private Lott Allen didn’t enlist as a cook; he enlisted as a soldier, couldn’t cut it, and (it seems) wasn’t very good as a cook, either.

Posting elsewhere, the researcher takes her assumption about Private Allen and spins it off into a grand, sweeping claim encompassing thousands or tens of thousands of others:

The question is: Were there cooks, teamsters, laborers in the Union Army United States Colored Troops? The answer is yes. As an example in the image of this post, Private Allen Lot [sic.], a soldier with the Union Army 21st United States Colored Troops, served as an “On [sic.] Duty Cook.” See Private Allen Lot’s Union Soldier Service Record (NARA Catalog ID 300398).

Therefore, with this preponderance of the evidence, African-Americans on Confederate Soldier Service Records (muster rolls) who are listed as cooks, teamsters, laborers, etc. should likewise be called soldiers. The sun rises and it shines on us all.

She takes a single notation that this man was assigned as a cook and then extrapolates that to argue that all “who are listed as cooks, teamsters, laborers, etc. should likewise be called soldiers.” She makes what is formally known as a “converse accident,” but is a simple and obvious logical fallacy: she reasons that this soldier was a cook; therefore all cooks were soldiers. (And teamsters, and laborers. . . .)

It’s hard to know whether this researcher bothered to look at all of Allen’s CSR or just didn’t understand it, but it really doesn’t matter. Either way she misrepresents Allen’s actual situation, and then uses that flawed example to make a sweeping rhetorical argument applied to tens of thousands of men in an entirely different army.

This is, sadly, typical of most of the “research” that goes into BCS advocacy; it’s a mile wide and a half-inch deep. It’s pulling out a word here, a line there, and announcing it as “proof” with little consideration of the full record, even when, as in this case, it’s readily available. It’s about adding names to a list, with little or no real understanding of the larger story, or the historical context of the claim being made. It’s just unbelievably superficial.

There’s no question that tens of thousands of African Americans went into the field with the Confederate army as cooks, personal servants, teamsters, laborers, and so on. Some were free; most were slaves. Some undoubtedly went willingly, but far more went with with some degree of coercion (legal, economic, physical) guiding their steps. Some saw combat, even though very, very few were officially in a combat role. There is a tremendous, untapped resource there for serious research. But they were not formally considered soldiers at the time, by either the Confederate or Union army. Robert E. Lee didn’t recognize these men as soldiers; he thought such pretensions made a fine joke. Howell Cobb didn’t recognize these men as soldiers. Kirby Smith didn’t see these men as soldiers. So why do some people today, like this researcher, devote so much effort to retroactively designate them so? Why is “proving” that point so much more important than telling their actual stories as individuals? Sure, this researcher finds Lott Allen and William Dove useful for making an analogy, but does she offer any additional information about them? (Hint: if you’ve read this far, you already know more about Lott Allen than you’re ever likely to find on the researcher’s site.)

I regret feeling obligated to make this post at all, and have no doubt it will be framed as a personal attack on this particular researcher’s character. It’s not; I’ve repeatedly said before, and still believe, that she is sincere and well-intentioned in her efforts. But it’s also clear that she doesn’t understand the materials she’s working with, and has no sense of her own limitations in that regard. But she is viewed as a among BCS advocates as a leading researcher on the subject, and maintains an extensive website dedicated to it. If she is to be respected and valued as a researcher, she needs to be subject to the same fact-checking on her research and methodology that the rest of us are; she doesn’t get a pass because she’s not professionally trained, or because she’s well-intentioned.

There’s a saying, much quoted by True Southrons™, that “history is written by the winners.” This reflects their sincere belief that their own preferred historical narrative is somehow suppressed by professional historians and censored in academic curricula. That’s wrong; history is history, regardless of who writes it. But the work they do needs to stand up to scrutiny, and most of it just doesn’t.

_______________

“When we arm the slaves, we abandon slavery.”

In the winter of 1864-65, as the war ground down to its dénouement, the proposal to enlist slaves as Confederate soldiers became an increasingly heated matter of public discussion. While proposals to do so had popped up from time to time throughout the war, it wasn’t until the last winter of the conflict that they attracted serious attention by public officials, and the the ensuing debate was rancorous. Robert E. Lee himself reluctantly concluded that the enlistment of slaves as soldiers was an essential move, and endorsed a plan that would reward men who enlisted under it with their freedom. The Confederate Congress finally approved a plan for the enlistment of slaves — though without emancipation in return for their service — in the middle of March 1865, less than three weeks before the evacuation of Richmond. Too little, too late.

Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown (right, 1821-94) was one of several high-ranking public officials who went on record to oppose any such measure, while it was still being debated in Richmond. In an address to both houses of the Georgia Assembly on February 15, 1865, Brown vehemently rejected both the notion that slaves could be made soldiers, and that the institution of slavery could survive the the resulting upheaval of social and racial order. Brown’s address was printed in the Athens, Georgia, Southern Watchman on March 1, 1865 (requires DjVu plug-in):

Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown (right, 1821-94) was one of several high-ranking public officials who went on record to oppose any such measure, while it was still being debated in Richmond. In an address to both houses of the Georgia Assembly on February 15, 1865, Brown vehemently rejected both the notion that slaves could be made soldiers, and that the institution of slavery could survive the the resulting upheaval of social and racial order. Brown’s address was printed in the Athens, Georgia, Southern Watchman on March 1, 1865 (requires DjVu plug-in):

Arming the Slaves

The [Jefferson Davis] administration, by its unfortunate policy, having wasted our strength and reduced our armies, and being unable to get free men into the field as conscripts, and unwilling to accept them in organizations with officers of their own choice, will, it is believed, soon resort to the policy of filling them up by the conscription of slaves.

I am satisfied that we may profitably use slave labor, so far as it can be spared from agriculture, to do menial service in connection with the army, and thereby enable more free white men to take up arms; but I am quite sure that any attempt to arm slaves will be a great error. If we expect to continue the war successfully, we are obliged to have the labor of most of them in the production of provisions.

But if this difficulty were surmounted, we cannot rely on them as soldiers, They are now quietly serving us at home, because they do not wish to go into the army, and they fear, if they leave us, the enemy will put them there. If we compel them to take up arms, their whole feeling and conduct will change, and they will leave us by the thousands. A single proclamation by President Lincoln – that all who will desert us after they are forced into service, and go over to him, shall have their freedom, be taken out of the army, and be permitted to go into the country in his possession, and receive wages for their labor – would disband them by brigades. Whatever may be our opinion of their normal condition or their true interest, we can not expect them if they remain with us, to perform deeds of heroic valor when they are fighting to continue the enslavement of their wives and children. It is not reasonable for us to demand it of them, and we have little cause to expect the blessing of Heaven upon our effort if we compel them to perform such a task.

If we are right, and Providence designed them for slavery, He did not intend that they should be a military people. Whenever we establish the fact that they are a military race, we destroy our whole theory that they are unfit to be free.

But it is said we should give them their freedom in case of their fidelity to our cause in the field; in other words, that we should give up slavery, as well as our personal liberty and State sovereignty, for independence, and should set all our slaves free if they will aid us to achieve it. If we are ready to give up slavery, I am satisfied we can make it the consideration for a better trade than to give it for the uncertain aid which they might afford us in the military field. When we arm the slaves, we abandon slavery. We can never again govern them as slaves, and make the institution profitable to ourselves or to them, after tens of thousands of them have been taught the use of arms, and spent years in the indolent indulgences of camp life.

Brown’s argument that “whenever we establish the fact that they are a military race, we destroy our whole theory that they are unfit to be free,” mirrors the position of his fellow Georgian, Howell Cobb, who had famously written the previous month to the Confederate Secretary of War, James Seddon. “If slaves make good soldiers,” Cobb warned, “our whole theory of slavery is wrong — but they won’t make soldiers.”

Brown then went on to reject the “monstrous doctrine” that the Confederate government had the authority to conscript slaves and emancipate them in return for their service, because to do so violated the fundamental right to property of the slaveholders. Such an act would constitute a “taking” of property that violated the most basic principles of the both national and state constitutions:

It can never be admitted by the State that the Confederate Government has any power directly or indirectly to abolish slavery. The provision in the Constitution which by implication authorizes the Confederate Government to take private property for public use only, authorizes the use of the property during the existence of the emergency which justified the taking., To illustrate: In time of war it may be necessary for the Government to take from a citizen a business house to hold commissary stores., This it may do (if a suitable one cannot be had by contract) on payment to the owner a just compensation for the use of the house. But the taking cannot change the title of the land, and vest it in the government. Whenever the emergency has passed, the Government can no longer legally hold the house, but is bound to return it to the owner. So the Government may impress slaves to do the labor of servants, as to fortify a city, if it cannot obtain them by contract, and it is bound to pay the owner just hire for the time it uses them. But the impressment can vest no title to the slaves in the Government for a longer period than the emergency requires the labor. It has not a shadow of right to impress and pay for a slave and set him free. The moment if ceases to need the labor the use reverts to the owner who has the title. If we admit the right of the Government to impress and pay for slaves to free them, we concede its power to abolish slavery, and change our domestic institutions at its pleasure, and to tax us to raise money for that purpose. I am not aware of the advocacy of such a monstrous doctrine in the old Congress by any one of the radical class of abolitionists. It certainly never found an advocate in any Southern statesman.

No slave can ever be liberated by the Confederate government without the consent of the States. No such consent can ever be given by this State without a previous alteration in her Constitution. And no such alteration can be made without the consent of her people.

It’s useful to remember the context of Brown’s address. Brown was intimately tied into the Confederate government at all levels; having held office since 1857, he was the longest-serving governor in the Confederacy. He spoke to the General Assembly in Macon, because the state government had evacuated its usual seat of Milledgeville in advance of Sherman’s army. While Sherman bypassed Macon, he’d left Milledgevillein ruins, cut a sixty-mile-wide swathe through Georgia to Savannah, and even now was marching north into South Carolina. And yet, even in the death throes of the Confederacy, Brown simply could not fathom the enlistment of African American slaves as Confederate soldiers.

Real Confederates didn’t know about black Confederates.

__________

“My humanity revolted at taking the poor devils away from their homes.”

Over at the Encyclopedia Virginia Blog, Brendan Wolfe posts a letter written by Colonel William Steptoe Christian (right, 1830-1910) of the 55th Virginia Infantry during the Gettysburg campaign. Christian’s letter, written from camp, describes the campaign through the Maryland and Pennsylvania countryside so far, and the Confederate army’s efforts at foraging on the march. He also mentions the seizure of African Americans from the free soil of Pennsylvania:

Over at the Encyclopedia Virginia Blog, Brendan Wolfe posts a letter written by Colonel William Steptoe Christian (right, 1830-1910) of the 55th Virginia Infantry during the Gettysburg campaign. Christian’s letter, written from camp, describes the campaign through the Maryland and Pennsylvania countryside so far, and the Confederate army’s efforts at foraging on the march. He also mentions the seizure of African Americans from the free soil of Pennsylvania:

No houses were searched and robbed, like our houses were done, by the Yankees. Pigs, chickens, geese, etc., are finding their way into our camp; it can’t be prevented, and I can’t think it ought to be. We must show them something of war. I have sent out to-day to get a good horse; I have no scruples about that, as they have taken mine. We took a lot of negroes [sic.] yesterday. I was offered my choice, but as I could not get them back home I would not take them. In fact, my humanity revolted at taking the poor devils away from their homes.

They were so scared that I turned them all loose. I dined yesterday with two old maids. They treated me very well, and seemed greatly in favor of peace. I have had a great deal of fun since I have been here.

Christian’s letter is fascinating, both for what it says and what it doesn’t. Undoubtedly Colonel Christian’s perspective was shared by many Confederates, both officers and enlisted men. While he objected to searching and ransacking private residences, he had no qualms about the seizure of livestock for forage and even a personal mount for himself. And while he declined to take captured African Americans for himself personally, both on practical (“I could not get them back home”) and humanitarian grounds (“they were so scared that I turned them all loose”), he never questions whether he had the right to do so, not indeed if it was right to do so. Those larger questions simply aren’t part of his recorded consideration of the question, and one is left to imagine that, had his circumstances been different, might he have decided differently, as well.

Others in Lee’s army were not so scrupulous when it came to the well-being of their captives, many of whom had never been slaves at all, but were born free. In his essay, “Race and Retaliation: The Capture of African Americans During the Gettysburg Campaign,” David G. Smith uses original, primary sources like Christian’s letter to conclude that the total number of African Americans captured by Lee’s army and taken south during the Gettysburg campaign may have been more than a thousand.

_______________

In Which I Almost Agreed with Brag Bowling

My expectations for Brag Bowling’s contributions to the Washington Post‘s A House Divided group blog are, shall we say, not high. But is it too much ask that he not contradict himself in consecutive sentences? Apparently it is.

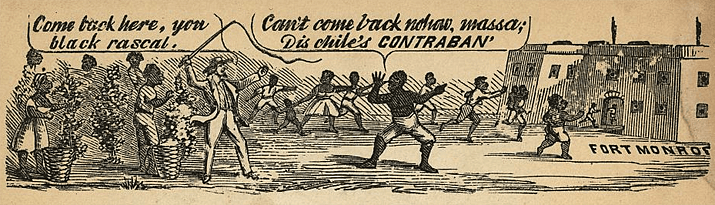

In answering the question, “how novel was Gen. Butler’s decision to treat escaped slaves as contraband and did he do it for humane or military reasons?”, Bowling launches into predictable tropes about Butler, identifying him as a “political general” in the first clause, and referencing the nickname “Beast” Butler, in the second sentence. Nothing surprising about that, if you’ve read his earlier contributions to the blog, a couple of which I’ve discussed here and here.

The whiplash-inducing contradiction in this new piece comes in the middle of the third paragraph, to wit:

Butler used the novel legal approach of viewing them as “property” and calling them “contraband of war”. This enabled Butler to ignore both the Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 which would have required that they be returned to their owners.

Did you catch that? Bowling first criticizes Butler as being wrong for recognizing slaves as property, and then wrong again for not returning them to their owners.

More to the point, Bowling seems to forget that Butler’s “novel legal approach of viewing them as ‘property’ ” conforms entirely to their status both under U.S. and Confederate law. Indeed, it was the explicit claim by Southerners of their property rights in the form of slaves that both drove their decision to secede from the Union, and subsequently provided Butler with the rationale to designate those same slaves as “contraband of war” when they were put to work building fortifications. It takes some real chutzpah to deny that slaves are property, then demand their return to you as their owner.

It’s true enough that Ben Butler was never a great battlefield tactician. But his contributions, which Bowling dismisses as being in the political arena, and (presumably) therefore irrelevant to his assessment, were substantial nonetheless. Bowling makes passing reference to Butler’s “ruthless occupation” of New Orleans, but omits that the “political general’s” quarantine and general cleanup of that city almost certainly saved hundreds, if not thousands of lives that would have been lost to that perennial scourge of the Crescent City, yellow fever. He omits Butler’s commitment to African American troops in the Federal army, and his willingness to test them in battle when other, better-known commanders like Sherman, were unwilling to give them a chance. And of course he omits Butler’s postwar career in Congress, when he wrote the first draft of the Civil Rights Act of 1871, a key measure that helped to reign in the abuses of the Ku Klux Klan in the South in the years after the war.

Bowling forgets to acknowledge those things, but you can be certain he remembered to mention the chamber pot with Butler’s picture in the bottom. One has to focus on the important stuff, I guess.

Oh, and that part where I almost agreed with Bowling? It was when I read this:

Northern abolitionists considered contrabands synonymous with emancipation even before Lincoln’s final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863. General Butler’s treatment of the contrabands, while mired in legal, political and cultural issues, was closely linked to the role of emancipation. When freedom did come to the slaves still in Confederate territory, the Union lines were flooded with the newly freed causing the U. S. government to implement new policies to provide them shelter, food, clothing and even some health care – all in part – because of Butler’s decisions at the beginning of the Civil War.

Then I looked again and realized I’d scrolled too far, and was reading the end of Frank Williams’ answer to the same question. My bad.

____________

Image: “Contraband, Fortress Monroe,” Library of Congress

Hari Jones Drops the Hammer on National Observance of Juneteenth

Hari Jones, Curator of the African American Civil War Museum, drops the hammer on the movement to make Juneteenth a national holiday, and the organization behind it, the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation (NJoF). He argues that the narrative used to justify the propose holiday does little to credit African Americans with taking up their own struggle, and instead presents them as passive players in emancipation, waiting on the beneficence of the Union army to do it for them. Further, he presses, the standard Juneteenth narrative carries forward a long-standing, intentional effort to suppress the story of how African Americans, in ways large and small, worked to emancipate themselves, particularly by taking up arms for the Union. He wraps up a stem-winder:

Certainly, informed and knowledgeable people should not celebrate the suppression of their own history. Juneteenth day is a de facto celebration of such suppression. Americans, especially Americans of African descent, should not celebrate when the enslaved were freed by someone else, because that’s not the accurate story. They should celebrate when the enslaved freed themselves, by saving the Union. Such freedmen were heroes, not spectators, and their story is currently being suppressed by the advocates of the Juneteenth national holiday. The Emancipation Proclamation did not free the slaves; it made it legal for this disenfranchised, enslaved population to free themselves, while maintaining the supremacy of the Constitution, and preserving the Union. They became the heroes of the Republic. It is as Lincoln said: without the military help of the black freedman, the war against the South could not have been won.

That’s worth celebrating. That’s worth telling. The story of how Americans of African descent helped save the Union, and freed themselves. Let’s celebrate the truth, a glorious history, a story of a glorious march to Liberty.

One gets the idea that Jones’ beef with the NJoF and its director, Dr. Ronald Myers, is about something more personal than mere historical narrative.

Jones makes a powerful argument, with solid points. But I think he misses something crucial, which is that in Texas, where Juneteenth originated, it’s been a regular celebration since 1866. It is not a modern holiday, established retroactively to commemorate an event in the long past; the celebration of Juneteenth is as old as emancipation itself. It was created and carried on by the freedmen and -women themselves:

Some of the early emancipation festivities were relegated by city authorities to a town’s outskirts; in time, however, black groups collected funds to purchase tracts of land for their celebrations, including Juneteenth. A common name for these sites was Emancipation Park. In Houston, for instance, a deed for a ten-acre site was signed in 1872, and in Austin the Travis County Emancipation Celebration Association acquired land for its Emancipation Park in the early 1900s; the Juneteenth event was later moved to Rosewood Park. In Limestone County the Nineteenth of June Association acquired thirty acres, which has since been reduced to twenty acres by the rising of Lake Mexia.

Particular celebrations of Juneteenth have had unique beginnings or aspects. In the state capital Juneteenth was first celebrated in 1867 under the direction of the Freedmen’s Bureau and became part of the calendar of public events by 1872. Juneteenth in Limestone County has gathered “thousands” to be with families and friends. At one time 30,000 blacks gathered at Booker T. Washington Park, known more popularly as Comanche Crossing, for the event. One of the most important parts of the Limestone celebration is the recollection of family history, both under slavery and since. Another of the state’s memorable celebrations of Juneteenth occurred in Brenham, where large, racially mixed crowds witness the annual promenade through town. In Beeville, black, white, and brown residents have also joined together to commemorate the day with barbecue, picnics, and other festivities.

It’s one thing to argue with another historian or community leader about the the historical narrative represented by a public celebration (think Columbus Day), but it’s entirely another to — in effect — dismiss the understanding of the day as originally celebrated by the people who actually lived those events, and experienced them at first hand.

What do you think?

_____________

h/t Kevin. Image: Juneteenth celebration in Austin, June 19, 1900. PICA 05476, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Juneteenth, History and Tradition

[This post originally appeared here on June 19, 2010.]

“Emancipation” by Thomas Nast. Ohio State University.

Juneteenth has come again, and (quite rightly) the Galveston County Daily News, the paper that first published General Granger’s order that forms the basis for the holiday, has again called for the day to be recognized as a national holiday:

Those who are lobbying for a national holiday are not asking for a paid day off. They are asking for a commemorative day, like Flag Day on June 14 or Patriot Day on Sept. 11. All that would take is a presidential proclamation. Both the U.S. House and Senate have endorsed the idea.

Why is a national celebration for an event that occurred in Galveston and originally affected only those in a single state such a good idea?

Because Juneteenth has become a symbol of the end of slavery. No matter how much we may regret the tragedy of slavery and wish it weren’t a part of this nation’s story, it is. Denying the truth about the past is always unwise.

For those who don’t know, Juneteenth started in Galveston. On Jan. 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. But the order was meaningless until it could be enforced. It wasn’t until June 19, 1865 — after the Confederacy had been defeated and Union troops landed in Galveston — that the slaves in Texas were told they were free.

People all across the country get this story. That’s why Juneteenth celebrations have been growing all across the country. The celebration started in Galveston. But its significance has come to be understood far, far beyond the island, and far beyond Texas.

This is exactly right. Juneteenth is not just of relevance to African Americans or Texans, but for all who ascribe to the values of liberty and civic participation in this country. A victory for civil rights for any group is a victory for us all, and there is none bigger in this nation’s history than that transformation represented by Juneteenth.

But as widespread as Juneteenth celebrations have become — I was pleased and surprised, some years ago, to see Juneteenth celebration flyers pasted up in Minnesota — there’s an awful lot of confusion and misinformation about the specific events here, in Galveston, in June 1865 that gave birth to the holiday. The best published account of the period appears in Edward T. Cotham’s Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, from which much of what follows is abstracted.

The United States Customs House, Galveston.

On June 5, Captain B. F. Sands entered Galveston harbor with the Union naval vessels Cornubia and Preston. Sands went ashore with a detachment and raised the United States flag over the federal customs house for about half an hour. Sands made a few comments to the largely silent crowd, saying that he saw this event as the closing chapter of the rebellion, and assuring the local citizens that he had only worn a sidearm that day as a gesture of respect for the mayor of the city.

Site of General Granger’s headquarters, southwest corner of 22nd Street and Strand.

A large number of Federal troops came ashore over the next two weeks, including detachments of the 76th Illinois Infantry. Union General Gordon Granger, newly-appointed as military governor for Texas, arrived on June 18, and established his headquarters in Osterman Building (now gone) on the southwest corner of 22nd and Strand. The provost marshal, which acted largely as a military police force, set up in the Customs House. The next day, June 19, a Monday, Granger issued five general orders, establishing his authority over the rest of Texas and laying out the initial priorities of his administration. General Orders Nos. 1 and 2 asserted Granger’s authority over all Federal forces in Texas, and named the key department heads in his administration of the state for various responsibilities. General Order No. 4 voided all actions of the Texas government during the rebellion, and asserted Federal control over all public assets within the state. General Order No. 5 established the Army’s Quartermaster Department as sole authorized buyer for cotton, until such time as Treasury agents could arrive and take over those responsibilities.

It is General Order No. 3, however, that is remembered today. It was short and direct:

Headquarters, District of Texas

Galveston, Texas, June 19, 1865General Orders, No. 3

The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there ro elsewhere.

By order of

Major-General Granger

F. W. Emery, Maj. & A. . G.

What’s less clear is how this order was disseminated. It’s likely that printed copies were put up in public places. It was published on June 21 in the Galveston Daily News, but otherwise it is not known if it was ever given a formal, public and ceremonial reading. Although the symbolic significance of General Order No. 3 cannot be overstated, its main legal purpose was to reaffirm what was well-established and widely known throughout the South, that with the occupation of Federal forces came the emancipation of all slaves within the region now coming under Union control.

The James Moreau Brown residence, now known as Ashton Villa, at 24th & Broadway in Galveston. This site is well-established in local tradition as the site of the original Juneteenth proclamation, although direct evidence is lacking.

Local tradition has long held that General Granger took over James Moreau Brown’s home on Broadway, Ashton Villa, as a residence for himself and his staff. To my knowledge, there is no direct evidence for this. Along with this comes the tradition that the Ashton Villa was also the site where the Emancipation Proclamation was formally read out to the citizenry of Galveston. This belief has prevailed for many years, and is annually reinforced with events commemorating Juneteenth both at the site, and also citing the site. In years past, community groups have even staged “reenactments” of the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation from the second-floor balcony, something which must surely strain the limits of reasonable historical conjecture. As far as I know, the property’s operators, the Galveston Historical Foundation, have never taken an official stand on the interpretation that Juneteenth had its actual origins on the site. Although I myself have serious doubts about Ashton Villa having having any direct role in the original Juneteenth, I also appreciate that, as with the band playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee” as Titanic sank beneath the waves, arguing against this particular cherished belief is undoubtedly a losing battle.

Assuming that either the Emancipation Proclamation (or alternately, Granger’s brief General Order No. 3) was formally, ceremonially read out to the populace, where did it happen? Charles Waldo Hayes, writing several years after the war, says General Order No. 3 was “issued from [Granger’s] headquarters,” but that sounds like a figurative description rather than a literal one. My bet would not be Ashton Villa, but one of two other sites downtown already mentioned: the Osterman Building, where Granger’s headquarters was located and where the official business of the Federal occupation was done initially, or at the United States Customs House, which was the symbol of Federal property both in Galveston and the state as a whole, and (more important still) was the headquarters of Granger’s provost marshal, Lieutenant Colonel Rankin G. Laughlin of the 94th Illinois Infantry. It’s easy to imagine Lt. Col. Laughlin dragging a crate out onto the sidewalk in front of the Customs House and barking out a brief, and somewhat perfunctory, read-through of all five of the general’s orders in quick succession. No flags, no bands, and probably not much of a crowd to witness the event. My personal suspicion is that, were we to travel back to June 1865 and witness the origin of this most remarkable and uniquely-American holiday, we’d find ourselves very disappointed in how the actual events played out at the time.

Maybe the Ashton Villa tradition is preferable, after all.

“Further legislation on that subject at this time is not advisable.”

Over at Civil War Memory, Kevin highlights a resolution passed by the North Carolina Legislature on February 3, 1865, “against the arming of slaves by the Confederate government, in any emergency that can possibly arise.” The timing of this is significant; not only was the Confederate Congress in Richmond actively debating the subject, but Sherman had just begun his march northward through the Carolinas, crossing the Georgia border into South Carolina two days before. Even with increasingly gloomy reports from Virginia on one side, and Sherman’s army — now rested and resupplied after taking Savannah just before Christmas — starting a new campaign from their south, the North Carolina Legislature could not envision “any emergency that can possibly arise” that would justify the arming of slaves.

Although the question of enlisting slaves had popped up from time to time in the local press, it appears that the Texas Legislature never considered the issue in a meaningful way, or adopted a formal and definitive resolution as did North Carolina. Part of the problem was timing; the Texas Legislature was not in session during the last months of the war, when the question of arming slaves came to a head. The last Texas Confederate Lege, the 10th, met in regular session in November and December 1863, with special called sessions in May 1864 and again in October/November 1864. The closest they got to the question was a motion referred to committee for consideration, for a resolution to urge Texas’ representatives and senators in Richmond to expand Confederate national laws for increased impressment of slaves as labor. The committee declined, reporting back to the Speaker of the House that “in their opinion the impressment law of the Confederate States now in force makes sufficient provisions for the impressment of Negroes, and that further legislation on that subject at this time is not advisable.”

Governor Pendelton Murrah (right) did, however, make a passing reference to slave labor in connection with eliminating the various exemptions from service that white men were claiming to remain in civilian jobs at home. In an address to both houses of the Lege at the beginning of the 10th Legislature, he argued (p. 21, 10.4MB PDF) that

Governor Pendelton Murrah (right) did, however, make a passing reference to slave labor in connection with eliminating the various exemptions from service that white men were claiming to remain in civilian jobs at home. In an address to both houses of the Lege at the beginning of the 10th Legislature, he argued (p. 21, 10.4MB PDF) that

The swarms of men engaged in profitable business on their own accounts, who are exempted from, or avoid military service upon one pretext or another — the thousands occupied in driving teams and cattle for the government and government contractors must be placed in their respective companies, and replaced with Negroes. The able-bodied soldiers and employees about the posts and towns must take the field and their places be supplied by the old, the very young, and the infirm.

It doesn’t appear that the prospect of enlisting slaves in Texas was ever a serious enough question to generate substantive discussion or debate in Austin. It was a proposition, it seems, not even worthy of formal consideration.

______________

Image: Texas State Capitol, Austin, in the 1870s. Lawrence T. Jones III Texas Photographs, Southern Methodist University, Central University Libraries, DeGolyer Library.

USCT Burials Marked in Wilmington

A couple of my readers have pointed me to news stories on Thursday’s dedication of a new historical marker outside the Wilmington, North Carolina National Cemetery. It’s believed that around 500 officers and enlisted men from USCT regiments who died during the Wilmington campaign are buried there, many in unmarked graves. The 4thU.S. Colored Infantry, profiled in the previous post, served in the campaign and it is thought that some of its members are interred at the site.

In a ceremony organized by the city’s Commission on African-American History, Mayor Saffo presented a special certificate of appreciation to Fred Johnson, a local Civil War re-enactor who had researched the story of the black soldiers buried in Wilmington.

Johnson and retired Lt. Col. James C. Braye had organized a lobbying campaign to have the marker erected by the N.C. Department of Cultural Resources.

“Oh, what a morning!” shouted Johnson, wearing the uniform of a Civil War-era artillery sergeant.

He thanked Chris Fonvielle, a historian with the University of North Carolina Wilmington who serves on the state committee that approves new highway markers. Fonvielle had been a strong advocate for the project, Johnson said.

Spectators included both re-enactors of U.S. Colored Troops in Union blue and members of Cape Fear Chapter No. 3 of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, many of whom dressed in black as hoop-skirted Civil War widows.

The re-enactors gave a loud “Huzzah!” as Saffo handed the certificate to Johnson.

Thanks for the heads-up on the story, folks.

_____________

First Sergeant Henry, Is that You?

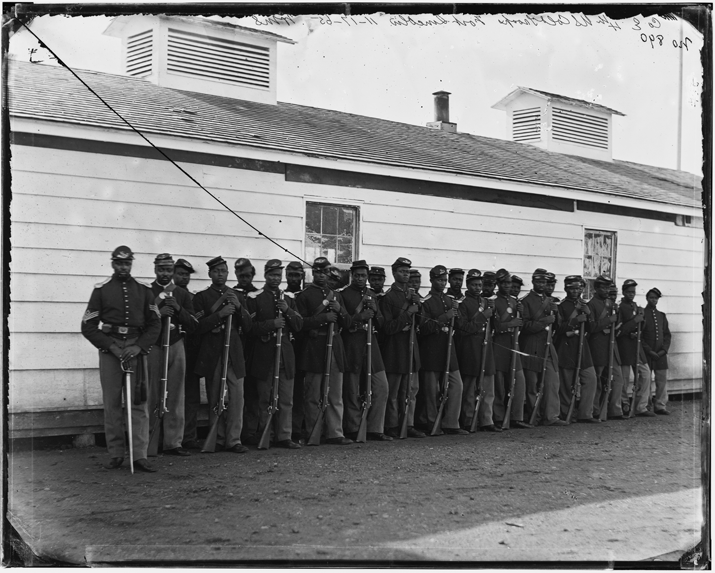

You’ve seen this picture a hundred times.

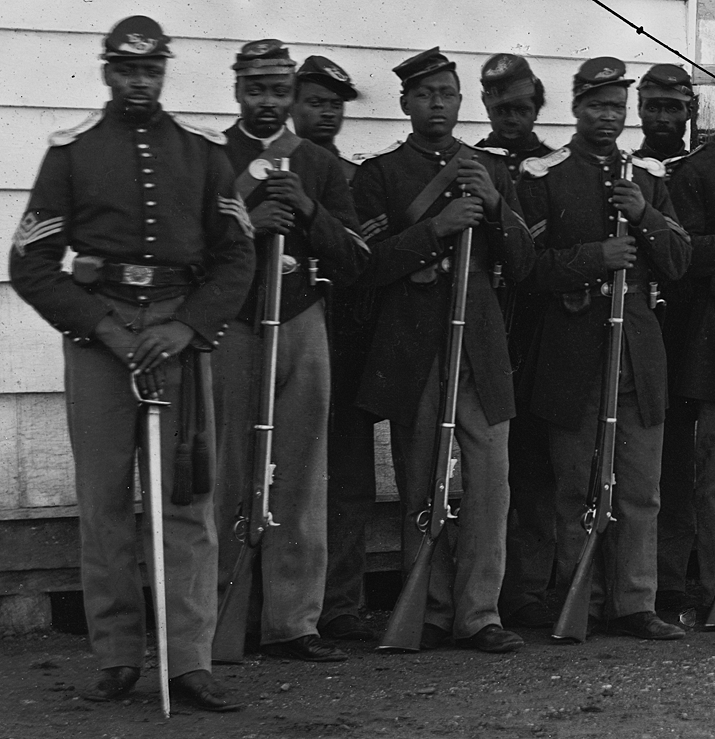

It appears in almost every book and article about African Americans serving in the Union Army, and on blogs dedicated to the subject. I’ve even used it here, myself. It’s an image of Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry. I’d always guessed that this image was taken early in the 4th’s history, perhaps during its training phase; the uniforms and equipment (including polished shoulder scales) seemed too pristine, too precisely-placed (below). These are, I decided, garrisoned soldiers, not men who’ve been spending their time recently on the march or living in the field.

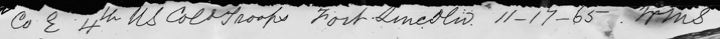

My reasoning was right, but my conclusion about the date was wrong. The image was not made during the 4th USCT’s working-up period. On the upper edge of the full image, available from the Library of Congress, the notation is scratched on the glass plate negative reads, “Co E 4th US Col’d Troops Fort Lincoln 11-17-65. WMS [William Morris Smith, the photographer].”:

It’s a postwar image, taken seven months after Appomattox. So they are garrisoned troops, well rested, in fresh uniforms and accoutrements. But they’re probably also all combat veterans, of hard-fought actions at Petersburg, Chaffin’s Farm/New Market Heights, and Fort Fisher. These men are not green recruits; they’re veterans, men who’ve seen some of the hardest fighting in the east in the last year of the conflict.

I had always guessed this image was a detachment of Co. E; in fact, it may be all of the enlisted men in Company E as it was at the end of the war.

We were discussing this image the other day at Coates’ blog, and I wondered if it was possible to identify any of the men in the image. There are twenty-seven men visible in the image; at least six of them are non-commissioned officers. It may be impossible to identify the others, but there should have been only a single First Sergeant on the company roster in November 1865; can he be identified?

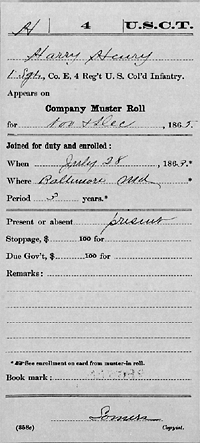

It’s actually a straightforward, two-step process. First, the NPS Soldiers & Sailors System database allows users to search by regiment, and pull up names of officers and enlisted men assigned to it. Helpfully, the database includes each soldier’s initial and final rank, so it’s a simple matter to identify a few likely candidates. Second, cross-check those men’s compiled service records via Footnote, to confirm each individual’s duty assignment and dates in rank. Using this method, it was quickly determined that in November 1865, the First Sergeant of Co. E, 4th USCT was First Sergeant Harry Henry. You can read his service record here, via Footnote (5.2MB PDF).

Locating a likely match in the NPS oldiers & Sailors System.

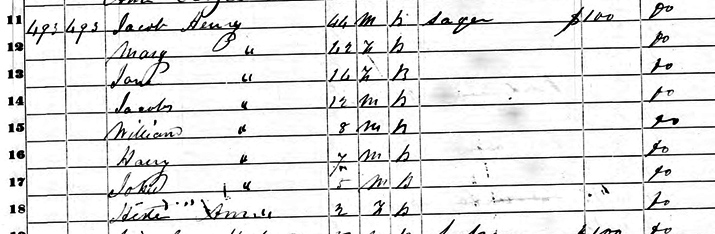

Harry Henry was born about 1842 on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. He was likely born free; he first appears in the 1850 U.S. Census, living with his father Jacob, a sawyer, and his wife, Mary, in or near Cambridge in Dorchester County. Harry was the third of at least six siblings; the others were Jane, born c. 1834; Jacob (Jr.), born c. 1838; William, born c. 1842; John, born c. 1845, and Ann, born c. 1848. At the time of the census, neither Jacob nor Mary could read or write, but Jacob held title to land valued at $100.

The Jacob and Mary Henry family in the 1850 U.S. Census.

By the time of the 1860 U.S. Census, most of the older children were no longer part of the household, but Harry, age 19, was still living with his parents and, like his father, earning his living as a sawyer. Ann, now aged 13, lived with them as well. As with the earlier census, none of the adults — now including Harry — were recorded as being able to read or write.

Harry Henry enlisted in Company E of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry at Baltimore on July 28, 1863, a few weeks after recruitment for the USCTs began. He enlisted for a term of three years. At the time he gave his age as 21 years, his height as five-foot-seven, with a “black” complexion, black eyes and curly hair. His occupation was listed as “farmer.” It appears that on that same day Harry’s older brothers, Jacob and William, enlisted in the same company. Jacob would be wounded at New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, but eventually return to duty. Jacob was apparently a crack shot, as he spent much of his enlistment on detached service, away from the regiment, with a sharpshooters’ unit. Both Jacob and William would survive the war and, with Harry, muster out of the 4th USCT as a Sergeant and Corporal respectively, in May 1866.

Henry was appointed Corporal at the time of his enlistment, but his service record carries few notations that give additional details of his service for his first year in the army. There are no notices of pay stoppage for lost gear, for example (a common entry for enlisted troops), nor notation of illness or injury. Beginning in July 1864, his pay records carry the notation, “free on or before April 19, 1861,” reflecting the army’s agreement to pay black soldiers the same as white, and to award the difference in back pay to those men who had been free before the outbreak of the war.

Sgt. Maj. Christian Fleetwood saves the 4th USCT’s colors at New Market Heights, September 29, 1864. Harry Henry’s brother Jacob was wounded in that action, and Co. E’s First Sergeant, Isaac Harroll, was killed. Image: “Field of Honor “by Joseph Umble, © County of Henrico, Virginia. Via The Sable Arm blog.

Company E’s original First Sergeant, Isaac Harroll, was killed at Chaffin’s Farm/New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, the same day Jacob Henry was wounded. Four other men of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, including Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood, would earn Medals of Honor in that action.The 4th took terrific casualties that day — 97 dead, 137 wounded and 14 missing.

Company E’s original First Sergeant, Isaac Harroll, was killed at Chaffin’s Farm/New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, the same day Jacob Henry was wounded. Four other men of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, including Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood, would earn Medals of Honor in that action.The 4th took terrific casualties that day — 97 dead, 137 wounded and 14 missing.

Corporal Harry Henry was promoted to take Harroll’s place as First Sergeant of the company two weeks after the action, on October 14. He would remain First Sergeant of Company E for the remainder of the regiment’s time in service, including in November 1865 (right) when the famous photo was taken. There are few further notations describing his service through the end of the war; he mustered out with the regiment on May 4, 1866 in Washington, D.C.

I’ve found few solid leads on Harry Henry’s life after the war. There was a Harry Henry of about the right age living in Snow Hill, Maryland — about 40 miles from where the sawyer’s son Harry Henry had grown up — at the time of the 1900 U.S. Census. That later Harry Henry was married to a Sally M. Henry, age 51, with the notation that they’d been married for 35 years. It’s not certain, though, that these two Harry Henrys were in fact the same man. After 1900, the trail grows cold, and I really don’t know with certainty what became of Harry Henry after his discharge in 1866.

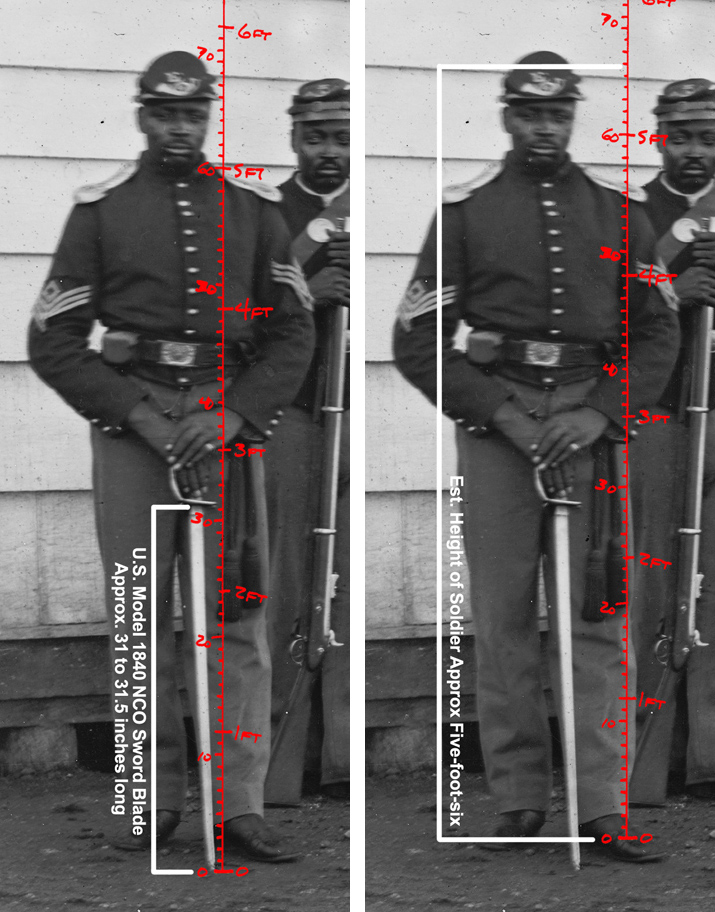

So that’s the circumstantial case for the man in the photo being Harry Henry. Does the photo itself yield any clues? Yes, it does.

Looking at the overall image, the First Sergeant at first appears substantially taller than the other soldiers. But that could be a trick of perspective; he’s also closer to the camera than any of the others. Fortunately, he holds in his hands a tool we can use to estimate his height, what appears to be a U.S. M1840 Non-commissioned officer’s sword. The M1840 had a blade variously described as being between 31 and 31.5 inches long; because he’s holding it close to the vertical, we can use that blade as a rough scale to determine the First Sergeant’s height.

At left, a six-foot scale has been aligned and adjusted to match the blade on the sword. (The left side of the scale is marked in inches, the right in feet.) At right, that same scale has been moved to align with the approximate location of the bottom of the man’s heel. The scale suggests the man’s overall height at around five-foot-six, very close to Henry’s recorded height of five-foot-seven. While this estimate is only approximate — neither the bottom of the man’s foot not the top of his head are visible — it’s very consistent with the man in the image being Harry Henry.

Can we definitively prove that the First Sergeant in the famous photo is Harry Henry? No. But both the documentary record and careful analysis of the photo suggest strongly that it is.

If anyone out there has additional information on Harry Henry, either his service with the 4th USCT or his life afterwards, I’d love to know it.

______________

30 comments