South Carolina Flag Dispute: Heritage vs. Heritage

In putting together my recent post on the rancorous neighborhood dispute over a resident’s display of a Confederate Battle Flag in an historically African American neighborhood, I made a passing reference to the fact that the community itself had been founded by former USCTs. In retrospect, I “buried the lede,” as they say, and gave that aspect of the story short shrift — it likely plays a much bigger role in how that community identifies itself, and in its reaction to Ms. Caddell’s display:

Among [Brownsville’s] founding families were at least 10 soldiers stationed to guard the Summerville railroad station at the close of the Civil War. They were members of the 1st Regiment, United States Colored Troops, part of a force of freedmen and runaway slaves who made history with their service and paved the way for African Americans in the military.

At least some of the men were from North Carolina plantations. When the war ended they stayed where they were, living within hailing distance of each other along the tracks. Some of them lived on the “old back road” out of town where outrage has erupted recently over a resident flying a Confederate battle flag. Their ancestors [sic., descendants] still live there.

It’s a striking note in a controversy over heritage that has raised hackles across the Lowcountry and the state.

The community’s past is an obscure bit of the rich history in Summerville, maybe partly because for years the families kept it to themselves. They were the veterans and descendants of Union troops, living through Jim Crow and segregated times in a region that vaunted its rebel past.

The great-great-grandfather of Jordan Simmons III was among them. But growing up in Brownsville a century later, all Simmons remembers hearing about Jordan Swindel, his ancestor, is that he was a runaway slave who joined the Army. The rest, he says simply, “was not talked about.” He didn’t find out about it until he was an adult doing research on the Civil War and the troops and came across Swindel’s name.

Now he’s at work on a book about his family and the Brownsville heritage. Other 1st Regiment surnames in the community include Jacox, Berry, Campbell, Edney and Fedley.

Simmons, 64, has lived through some history of his own. He was one of the South Carolina State University students injured in the infamous 1968 Orangeburg Massacre. He too served in the U.S. Army, a 29-year veteran who fought in Vietnam with the 101st Airborne infantry and retired as a lieutenant colonel. He now lives in Virginia.

It overwhelmed him to see his great-great-grandfather’s name on the wall of honor three years ago when he visited the African-American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C. Pvt. Swindel fought in four battles in nine months in 1864, from Florida — where he was wounded — to Honey Hill, S.C. Simmons wishes he would have sought out that history when he was younger.

As I said previously, neither side in this dispute seems much interested in letting go of this game of one-upsmanship. The historical circumstances surrounding the town’s founding don’t change the core legal issues at hand, but given that the Southron Heritage folks routinely dismiss criticism of the Confederate Flag as “political correctness” or as unfairly tarnishing an honored symbol of the Confederacy with its use by hate groups, it’s interesting to see a case where the protestor’s case against the flag is so explicitly based in the very same “heritage” argument that the flag’s proponents righteously embrace. For at least some local residents, pushback against the CBF is every bit as grounded in the history of the American Civil War, and honoring one’s ancestors, as Ms. Caddell’s display of it. For them, it’s personal, and for exactly the same reasons.

I don’t know what the answer here is. What is clear, though, is that there’s an historical dimension to this case — very real and very valid, by the same “heritage” standard that the folks in (say) the South Carolina League of the South embrace for themselves — that needs much wider dissemination, and it plays a big role in how that community thinks and feels and reacts.

_____________

Image: Soldiers of the 1st USCT on parade. Library of Congress.

Do (Ever-Higher) Fences Make Good Neighbors?

Some folks may recall the case last year in South Carolina where Annie Chambers Caddell moved into a historically African American neighborhood, and put a Confederate flag on the front of her house. Her neighborhood’s origins go back to the close of the Civil War, when the area was settled by several former members of the 1st USCT, who’d been stationed there at the end of their military service. Caddell, who is white, argued she was honoring her Confederate ancestors; her neighbors, not surprisingly, see the flag as a symbol of something else entirely.

Inevitably there were protests against Caddell, and counter-protests in response (above). It got worse; someone reportedly threw a rock through Caddell’s front window. There has been inflammatory, over-the-top rhetoric on both sides. Not surprisingly, both sides have chosen to escalate the dispute.

Earlier this year, two solid 8-foot high wooden fences were built on either side of Annie Chambers Caddell’s modest brick house to shield the Southern banner from view.

Late this summer, Caddell raised a flagpole higher than the fences to display the flag. Then a similar pole with an American flag was placed across the fence in the yard of neighbor Patterson James, who is black. . . .

“I’m here to stay. I didn’t back down and because I didn’t cower the neighbors say I’m the lady who loves her flag and loves her heritage,” said the 51-year old Caddell who moved into the historically black Brownsville neighborhood in the summer of 2010. Her ancestors fought for the Confederacy.

Last October, about 70 people marched in the street and sang civil rights songs to protest the flag, while about 30 others stood in Caddell’s yard waving the Confederate flag.

Opponents of the flag earlier gathered 200 names on a protest petition and took their case to a town council meeting where Caddell tearfully testified that she’s not a racist. Local officials have said she has the right to fly the flag, while her neighbors have the right to protest. And build fences.

“Things seemed to quiet down and then the fences started,” Caddell said. “I didn’t know anything about it until they were putting down the postholes and threw it together in less than a day.”

Aaron Brown, the town councilman whose district includes Brownsville, said neighbors raised money for the fences.

“The community met and talked about the situation,” he said. “Somebody suggested that what we should do is just go ahead and put the fences up and that way somebody would have to stand directly in front of the house to see the flag and that would mediate the flag’s influence.”

Caddell isn’t bothered by the fences and said they even seem to draw more attention to her house.

“People driving by here because of the privacy fences, they tend to slow down,” she said. “If the objective was to block my house from view, they didn’t succeed very well.”

You can see where this is going; by this time next year, one side or the other will have put up a big-ass flag.

More seriously, this is just headache-inducing. The only people benefiting from this rancorous business are flagpole installers and the local lumber yard.

I don’t know what the answer here is. Caddell has a right to display her flag; her neighbors have a right to make their objection to it clear. But neither benefits from continually upping the ante, nor does it help to bring in outside groups and activists to use this case to fight a larger proxy battle for historical memory, as recently happened in Lexington. That only serves to harden the resolve of all concerned, by raising the purported stakes beyond what they actually are. I hope Caddell and her neighbors eventually come to some sort of resolution in this business. But that doesn’t seem likely anytime soon, so long as all parties insist on following the tired script of action and reaction, and insist on having others fight their rhetorical battles instead of talking to each other like responsible grown-ups.

_________

Image (Original Caption): Brownsville Community resident Tim Hudson (right) tells H.K. Edgerton of Ridgeville he looks “ridiculous” in his Confederate uniform as he stands with outside the home of Annie Chambers Caddell Saturday, October 16, 2010. Brownsville community members marched past Caddell’s home to protest her flying of the confederate flag outside her home in the predominantly black neighborhood. Hudson was not a marcher in the protest group. Photo by Alan Hawes, postandcourier.com.

Texas Drought Exposes African American Burial Site

Over at Interpreting Slave Life, Nicole Moore highlights a recent news item from north Texas, where a previously-unknown African American burial ground has been exposed by the drought in Navarro County, near Corsicana:

Forensics experts told Bailey the remains appear to belong to an African-American man, about 40 years old, who was likely a freed slave.

“We believe it was a person who worked on a plantation in that river bottom [sic.],” [Navarro County Sheriff’s Deputy Frank] Bailey said.

The reservoir is one of Tarrant County’s [i.e., Fort Worth’s] water sources.

Cemeteries were noted and moved before it was filled in the 1980s, but this small cemetery was not marked, and the graves did not have tombstones.

Boaters first found the remains in 2009 along the shoreline. But lake levels rose again within days, quickly reclaiming the site.

So, for three years, archaeologists and historians have waited for the reservoir to reveal them again.

The site was uncovered by the receding waters of the Richland Chambers Reservoir. It’s not actually a river bottom, but formed by the flow of Richland and Chambers Creeks. The Navarro County Times is also covering the story, as is the Corsicana Daily Sun.

There weren’t a lot of what what’s commonly thought of as plantations in that area in the mid-19th century. Navarro County had a total of 251 slaveholders in 1860, owning in aggregate 1,890 slaves. Seventeen slaveholders owned twenty or more slaves — one of the common standards for what designated a planter as opposed to a mere farmer — and only one of who owned more than a hundred.[1]

The largest slaveholder in Navarro County was Anderson Ingram (c. 1799 – c. 1875), who with three brothers purchased thousands of acres of land along the Trinity River, which forms the county’s eastern boundary.[2] In 1859, Ingram was actively farming 900 acres, on which his slaves cultivated 6,500 bushels of corn and 382 bales of cotton.[3]

Far more common were relatively small farming operations like that of Aaron Perry in neighboring Limestone County, who raised hogs and corn, much of the latter likely used for fattening the former before killing time in the fall.

I haven’t been able to locate Anderson Ingram’s property on plot maps from the General Land Office dated to 1858 and 1872, but if it was in the eastern part of the county, it was in the same general part of the county as the reservoir. In any event, the exact location of the site is held in confidence by local authorities to prevent its disturbance by both looters and the curious. There are likely more burials nearby, which may help present a more complete picture of north central Texas on the eve of secession.

[1] University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center. “Historical Census Browser.” Retrieved September 06, 2011, from the: http://fisher.lib.virginia.edu/collections/stats/histcensus/index.html.

[2] Christopher Long, “Ingram, Anderson,” Handbook of Texas Online (http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/fin07), accessed September 06, 2011. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

[3] Ralph A. Wooster, “Notes on Texas’ Largest Slaveholders, 1860,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly 65 (July 1961).

Image: The Richland Chambers Reservoir, Navarro County, as imaged in ArcGIS Explorer. In this view, which incorporates bathymetry data, the original courses of Richland and Chambers Creeks can be seen faintly. The city of Corsicana appears at upper left. Full-size image here.

Mustering Black Confederates

A new page added to the blog, indexing by category my previous postings on black Confederate soldiers.

____________

Image: Ransom Gwynn (seated) with white Confederate veterans at what was billed as the “Last Confederate Reunion” at Montgomery, Alabama in September 1944. Rev. Gwynn attended at least two Confederate reunions (1937 and 1944) on the claim that he had been a “body guard” to his former master, but historical records indicate Gwynn was likely not more than 11 years old, and perhaps as young as 8 or 9, when the war ended. Alabama Department of Archives and History.

“The work of soldiers amounts to very little.”

Just two days before Arthur Fremantle toured the batteries defending the eastern end of Galveston Island, the Confederate military engineer in charge of designing and building the defenses wrote out his report for the month of April 1863, outlining the work accomplished to date, and some of the challenges still to be overcome. Colonel Valery Sulakowski (1827-1873, right) was a Pole by birth, and a former officer in the Austrian army. After emigrating to the United States in the late 1840s, he worked as a civil engineer in New Orleans. He’d met General Magruder early in the war, in Virginia, and after the island was recaptured from Federal forces on New Years Day 1863, set about expanding the island’s defenses. Sulakowski had the reputation of a strict disciplinarian but, along with another immigrant engineering officer, Julius Kellersberger, is credited with quickly expanding the fortifications at Galveston and making the island a much more defensible post than it had been during the first eighteen months of the war.

Just two days before Arthur Fremantle toured the batteries defending the eastern end of Galveston Island, the Confederate military engineer in charge of designing and building the defenses wrote out his report for the month of April 1863, outlining the work accomplished to date, and some of the challenges still to be overcome. Colonel Valery Sulakowski (1827-1873, right) was a Pole by birth, and a former officer in the Austrian army. After emigrating to the United States in the late 1840s, he worked as a civil engineer in New Orleans. He’d met General Magruder early in the war, in Virginia, and after the island was recaptured from Federal forces on New Years Day 1863, set about expanding the island’s defenses. Sulakowski had the reputation of a strict disciplinarian but, along with another immigrant engineering officer, Julius Kellersberger, is credited with quickly expanding the fortifications at Galveston and making the island a much more defensible post than it had been during the first eighteen months of the war.

Sulakowski’s report, being essentially simultaneous with Fremantle’s observations, also give a better sense of what the British officer saw but declined to record in detail due to the sensitive military nature of the information. From the Official Records, 21:1063-64:

ENGINEER’S OFFICE, Galveston, April 30, 1863.

Capt. EDMUND P. TURNER,

Assistant Adjutant-General, BrownsvilleCAPTAIN:

I have the honor to make the following report for the month of April, 1863:

Fort Point–casemated battery.–The wood, iron, and earth work was completed during this month; five iron casemate carriages constructed; the guns mounted; cisterns placed, and hot-shot furnace constructed. It has to be sodded all over, the bank being high and composed of sand. Two 10-inch mortars will be placed on the top behind breastworks.

Fort Magruder–heavy open battery.–The front embankment, traverses, platforms, and magazines were completed during this month; two 10-inch columbiads mounted. The Harriet Lane guns are not mounted, for want of suitable carriages, which are under construction. Bomb-proofs and embankment in the rear commenced and the front embankment sodded inside, top and slope. With the present force it will require nearly the whole of this month to complete it.

Fort Bankhead.–Guns were mounted and the railroad constructed during this month.

South Battery.–For want of labor the reconstruction of this battery was commenced within the last few days of the month; also the construction of the railroad leading to it.

Intrenchment of the town is barely commenced, for want of labor.

Obstructions in the main channel.–Since the destruction of the rafts by storm, before they could be fastened to the abutments, this plan of obstruction had to be abandoned for the want of material to repair the damage done. The present system of obstructing consists of groups of piles braced and bolted and three cable chains fastened to them, the groups of piles in the deepest part of the channel to be anchored besides. This was the first plan of obstructing the channel on my arrival here; but being informed by old sailors and residents that piles could not be driven on account of the quicksand, and not having the necessary machinery then to examine the bottom, it was rejected. Having constructed a machine for this purpose, it is certain that piles can be driven and are actually already driven half across. This obstruction will be completed and the chains stretched from abutment to abutment by the 10th of May. Sketch, letter A, represents the work.

Obstructions at the head of Pelican Island.–Two-thirds done. It will require the whole of May to complete this obstruction and erect the casemated sunken battery of two guns, as proposed in my last report. These works are greatly retarded by the difficulty of procuring the material.

Pelican Spit ought to be fortified, as submitted in my last report, with a casemated work. For its defense two 32-pounders and one 24-pounder can be spared. This work is of great importance, but it had to be postponed until the intrenchments around the town shall be fairly advanced.

The force of negroes [sic.] on the island consists of 481 effective men. Of these 40 are at the saw-mills, 100 cutting and carrying sod (as all the works are of sand, consequently the sodding must be done all over the works), 40 carrying timber and iron, which leaves 301 on the works, including [harbor] obstructions. The whole force of negroes consists, as above, of 481 effective, 42 cooks, 78 sick; total, 601.

In order to complete the defenses of Galveston it will require the labor of 1,000 negroes during three weeks, or eight weeks with the present force. The work of soldiers amounts to very little, as the officers seem to have no control whatever over their men. The number of soldiers at work is about 100 men, whose work amount to 10 negroes’ work.

Brazos River.–After having examined the locality I have laid out the necessary works, and Lieutenant Cross, of the Engineers, is ordered to take charge of the construction. Inclosed letter B is a copy of instructions given to Lieutenant Cross. Sketch, letter C, shows the location of the proposed works at the mouth of Brazos River.

Western Sub-District.–Major Lea, in charge of the Western Sub-District, sent in his first communication, copy of which, marked D, is inclosed. I respectfully recommend Major Lea’s suggestions with regard to procuring labor to the attention of the major-general commanding. I have ordered a close examination of the wreck of the Westfield, which resulted in finding one 8-inch gun already, and I hope that more will be found. Cash account inclosed is marked letter E; liabilities incurred and not paid is marked letter F.(*)

I have the honor to remain, respectfully, your obedient servant,

V. SULAKOWSKI.

My emphasis. “Major Lea,” mentioned in the last paragraph, is Albert Miller Lea, a Confederate engineer and staff officer who, after the Battle of Galveston four months before, had famously found his son, a U.S. naval officer aboard the Harriet Lane, mortally wounded aboard that ship.

Sulakowski’s report also mentions the importance of sodding the built-up earthworks, as the sand of which they were constructed would otherwise blow down in drifts. That technique was also used in the fortifications around Charleston, as in this detail (above) of a painting of Fort Moultrie by Conrad Wise Chapman. At the center of the image, African American laborers gather sand to be used in repairing the fort.

_____________

Image: Detail of “Fort Moultrie” by Conrad Wise Chapman. Museum of the Confederacy.

Slave Labor in the Defense of Galveston

Last week I had a post concerning (somewhat tangentially) the use of impressed African Americans as laborers on the defensive works at Galveston. It’s a subject that deserves much more close attention than I’ve had time to get into here, but I thought I’d pass along a few contemporary citations that address the prevalence of such laborers here, and the ongoing friction between the military, which needed every able-bodied hand it could get by any means, and slaveholders who were reluctant to turn their property over to the Confederacy for military labor.

Impressed slaves building fortifications at James Island, South Carolina. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Famous “Negro Cooks Regiment” Found — In My Own Backyard!

More crackerjack analysis from the leading online researcher of “black Confederates”:

Captain P.P. Brotherson’s Confederate Officers record states eleven (11) blacks served with the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery in the “Negro Cooks Regiment.” This annotation can be viewed on footnote.com. See the third line on the left. Also, the record is cataloged in the National Archives Catalog ID 586957 and microfilm number M331 under “Confederate General and Staff Officers, and Nonregimental Enlisted Men.”

Could this be one of the types of regiments many Confederate historians have documented as part of Confederate History?

Here’s the document in question:

Note that the critical phrase “Negro Cooks Regiment,” as quoted by the researcher, does not appear in the document, which is a routine statement of rations drawn for conscripted laborers. The actual text reads, “Provision for Eleven Negroes Employed in the Quarter Masters department Cooks Regt Heavy Artillery at Galveston Texas for ten days commencing on the 11th day of May 1864 & Ending on the 20th of May 1864.” There’s a similar document in the same collection, covering the period May 21 to 31, as well.

“Cook’s Regiment” is an alternate name for the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery. Like many Civil War regiments, it was widely known and referred to by the name of its commanding officer, Colonel Joseph Jarvis Cook (right). The regiment, formed from a pre-war militia unit, served at Galveston through most of the war, manning the artillery batteries around the island. The African Americans referred to in the document, attached to the regiment’s quartermaster, were likely used in maintaining the trenchwork and fortifications occupied by the regiment, or moving supplies and munitions between them. After the war, the former members of the regiment reorganized themselves as a sort of unofficial militia unit again, which eventually morphed into a social club. The Galveston Artillery Club exists right down to the present day. (Highly recommended for lunch, if you can score an invite.)

“Cook’s Regiment” is an alternate name for the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery. Like many Civil War regiments, it was widely known and referred to by the name of its commanding officer, Colonel Joseph Jarvis Cook (right). The regiment, formed from a pre-war militia unit, served at Galveston through most of the war, manning the artillery batteries around the island. The African Americans referred to in the document, attached to the regiment’s quartermaster, were likely used in maintaining the trenchwork and fortifications occupied by the regiment, or moving supplies and munitions between them. After the war, the former members of the regiment reorganized themselves as a sort of unofficial militia unit again, which eventually morphed into a social club. The Galveston Artillery Club exists right down to the present day. (Highly recommended for lunch, if you can score an invite.)

I wouldn’t expect most people, even Civil War buffs, to know what “Cook’s Regiment” was off the top of their heads, but it’s quite clear from the original document that it’s an artillery unit, as opposed to a regiment of cooks. The key phrasing quoted, “Negro Cooks Regiment,” is an outright fabrication. And 30 seconds with a search engine would’ve clarified the situation immediately.

Or maybe doing minimal due diligence like that is just a trick used by politically-correct, revisionist “pundits” like myself.

Forget interpretation. Forget analysis. Forget trying to understand the document within the context of the time and place it was written; these people don’t even seem capable of reading the documents they cite. This particular researcher has a track record of misreading documents, and drawing conclusions based on that misreading. A few weeks ago she claimed that the record of one African American, attached to a cavalry regiment, carried the notation, “has no home,” and went on to argue this showed special commitment to the Confederate cause: “with no home, [he] was not phycially [sic.] bound to the south. However, he stayed and served the Confederate States Army.” The actual notation, repeated again and again on cards throughout his CSR, was “has no horse.”

On another occasion, she quoted from a book on Camp Douglas, supposedly to show that a black servant held there had not been released as a former slave, but was held as a prisoner because the Federal authorities had determined that he was a bona fide soldier. This, she argued, was evidence that enslaved personal servants were deemed Confederate soldiers by the Union military. Unfortunately, the very next lines of the book she was quoting from verify that the prison camp did, after months of dragging their heels, determine the man was a slave, and released him on exactly those grounds by order of the Secretary of War.

And now, an entire regiment of “Negro cooks,” right here in my own home town. How did I miss that one? 😉

__________

Image: Order for the evacuation of Galveston, October 1862, signed by Col. Joseph Jarvis Cook, commanding Confederate troops on the island. Rosenberg Library, Galveston.

More on the “Negro Regiment” at Manassas

Update, December 2021: Reader Andersonh1 notes (see comments below) that “Quartermaster Pryor” appears to have been Col. John P. Pryor.

_________

We recently looked at what may be the origin of Frederick Douglass’ famous reference to black Confederate soldiers at Manassas, a report credited to a captured Confederate officer, one “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor,” supposedly of the 19th Mississippi, who is alleged to have ridden into Union lines by mistake, and happily provided all sorts of dubious information to his captors, including a description of “a regiment of negro [sic.] troops in the rebel forces, but [Pryor] says it is difficult to get them in proper discipline in battle array.” This account, with slight variation in the wording, was reprinted in newspapers across the North, and even incorporated — with substantial embellishment — into accounts of the battle in British papers such as the Guardian and the Illustrated London News.

In fact, the Confederate “Negro regiment” at Manassas seems to been the subject of much curiosity and speculation, and so turns up in multiple accounts of the battle, mostly in Northern papers. These accounts seem to go unmentioned by the advocates of BCS, which is curious given that these items make clear reference to such a unit. Or perhaps it’s not so curious, given that the descriptions of that unit and its activities are not always laudatory — not to the actions of the unit on the field, not to the trust placed in them by Confederate officers, nor to the loyalty of the men themselves. From the New York Times, August 17, 1861:

To-day a negro [sic.] arrived in our lines, and was brought to Gen. MANSFIELD’s office. He is one of the celebrated negro regiment. He fought at Bull Run, and made his escape with a servant of BEAUREGARD, after the battle, and succeeded in reaching Point of Rocks after great privation. He states that a regiment of one thousand slaves were brought from the Cotton States, and the perfection of their drill led to the organization of two regiments of negroes from Southeastern Virginia. Before the battle they were compelled to drill three hours a day, and for several hours beside were put to work in the entrenchments. At night they were penned up in the rear, and a strict guard placed over them. The Virginia negroes were nearly all anxious to escape, and would do so when the opportunity occurred. Those from the Cotton States, however, were fearful of doing so, having been made to believe that their lives would be in danger among our troops.

And this, from the Hartford, Connecticut Daily Courant, July 27, 1862:

Mr. James Plaskett has received a very interesting letter from his son, who was in the fight of Sunday, as a member of the 14th regiment New York militia. We make a few extracts. He says. . . :

One of the most inhuman occurrences which we were compelled to witness that day, was the destruction of a building erected by us for a temporary hospital. The building was about a mile from the batteries, and was filled with the wounded and dying, and they were also lying all around outside of the building. The rebels pointed their guns, and threw bomb-shells into the building, which blew it up and killed all who were in or around the building. A negro regiment came on the field after the fight was over, and killed those who showed signs of life.

The sight upon the battlefield, in view of the carnage, was a sad one to me; legs, arms and heads off.

And this, from the Madison, Wisconsin Daily Patriot, August 1, 1861:

A Minnesota boy, at Manassas, was rushed upon by four colored soldiers — full-blooded Africans; three were shot by Zouaves, the fourth attempted to pin him to the ground with his bayonet, which he parried, which gave a slight wound upon his thigh, and run into the ground its whole length, and, before he could extricate it, the boy shot him through the body, which was so ear that the blaze of the gun set his clothes on fire.

On the other hand, the New Orleans Commercial Bulletin eventually decided that all the talk of a “Negro regiment” at Manassas was a big misunderstanding (September 24, 1861, p. 2, col. 3):

The famous Black Horse Cavalry of the Potomac have been formed into a regiment, with Chas. W. Field for Colonel. Hencetofore the organization consisted of but one company. The “Black Horse” have become a terror to the Kangaroos, and their fame has even reached the other side of the water. One of the London papers speaks of them as a negro regiment armed by the Confederate States.

There’s a lot to digest in those passages, both spoken and unspoken. Thoughts?

______________

Frederick Douglass and the “Negro Regiment” at First Manassas

From the Douglass Monthly, September 1861:

It is now pretty well established, that there are at the present moment many colored men in the Confederate army doing duty not only as cooks, servants and laborers, but as real soldiers, having muskets on their shoulders, and bullets in their pockets, ready to shoot down loyal troops, and do all that soldiers may to destroy the Federal Government and build up that of the traitors and rebels. There were such soldiers at Manassas, and they are probably there still. There is a Negro in the army as well as in the fence, and our Government is likely to find it out before the war comes to an end. That the Negroes are numerous in the rebel army, and do for that army its heaviest work, is beyond question. They have been the chief laborers upon those temporary defences in which the rebels have been able to mow down our men. Negroes helped to build the batteries at Charleston. They relieve their gentlemanly and military masters from the stiffening drudgery of the camp, and devote them to the nimble and dexterous use of arms. Rising above vulgar prejudice, the slaveholding rebel accepts the aid of the black man as readily as that of any other. If a bad cause can do this, why should a good cause be less wisely conducted? We insist upon it, that one black regiment in such a war as this is, without being any more brave and orderly, would be worth to the Government more than two of any other; and that, while the Government continues to refuse the aid of colored men, thus alienating them from the national cause, and giving the rebels the advantage of them, it will not deserve better fortunes than it has thus far experienced.–Men in earnest don’t fight with one hand, when they might fight with two, and a man drowning would not refuse to be saved even by a colored hand.

This quote, and most specifically the first part of it in bold above, is often waved triumphantly as an incontrovertible bit of evidence that the Confederacy did enlist African Americans as bona fide soldiers, “having muskets on their shoulders, and bullets in their pockets.” Those who advocate for the existence of large numbers of BCS seem to view Douglass’ quote as a sort of rhetorical trump card, as though the assertion of someone so genuinely revered could not possibly be questioned. If Frederick Douglass said so, the thinking seems to be, then even the most biased, politically-correct historian has to accept that.

The truth, of course, is that Frederick Douglass’ claims are subject to same scrutiny as anyone else’s. It’s worth remembering that Douglass was neither a reporter nor an historian; he was, by his own happy admission, an agitator, and is his September 1861 essay excerpted above he was again making the case for the enlistment of African American soldiers in the Union army. If there were reports that the Confederate army had used black troops at First Manassas — a battle that by September was well understood as an embarrassing setback for Union forces — then that made all the more compelling case for the Lincoln administration to respond in kind.

But why did Douglass believe that there were, or at least plausibly might be, such units in the Confederate army? He lived in upstate New York, in Rochester; he was nowhere near the battle and saw nothing of it at first hand. He might have spoken to someone who claimed first-hand knowledge of the event, but there’s no evidence that that’s the source of the claim. Indeed, the opening clause of the passage — “it is now pretty well established” — acknowledges that Douglass was not writing about something he knew to a certainty, but rather a conclusion based on what were likely numerous reports, rumors and press items.

Earlier this week Donald R. Shaffer looked at the evidence of black Confederate soldiers taking part in First Manassas, and argued that Douglass may have been basing his claim on an exchange in the Congressional Globe that took place soon after the battle, in which the involvement of African Americans in the Confederate army in a variety of capacities is discussed. Shaffer concludes, “it is apparent from the debate above that some servants and other African Americans attached to both armies were armed. This did not make them soldiers officially, but it does make murkier the line dividing soldiers and civilians attached to the armies in the Civil War.”

Dr. Shaffer, author of After the Glory: The Struggles of Black Civil War Veterans and Voices of Emancipation: Understanding Slavery, the Civil War, and Reconstruction through the U.S. Pension Bureau Files, makes a solid argument. Douglass closely followed the political debates of the day, and may well have followed the discussion in the Congressional Globe. But I would respectfully submit that it’s even more likely that he believed there were black Confederate troops at Manassas because he read it in the newspaper. From the New York Tribune, July 22, 1861, p. 5 col. 4:

A Mississippi soldier was taken prisoner by Hasbrouck of the Wisconsin Regiment. He turned out to be Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor, cousin to Roger A. Pryor. He was captured on his horse, as he by accident rode into our lines. He discovered himself by remarking to Hasbrouck, “we are getting badly cut to pieces.” What regiment do you belong to?” asked Hasbrouck. “The 19th Mississippi,” was the answer. “Then you are my prisoner,” said Hasbrouck.

From the statement of this prisoner it appears that our artillery had created great havoc among the rebels, of whom there are 30,000 to 40,000 in the field under command of Gen. Beauregard, while they have a reserve of 75,000 at the Junction.

He describes an officer most prominent in the fight, and distinguished from the rest by his white horse, as Jeff. Davis. He confirms previous reports of a regiment of negro [sic.] troops in the rebel forces, but says it is difficult to get them in proper discipline in battle array.

This account, with minor changes to the wording, appeared in newspapers all across the North, and even in Canada, in the days immediately following the battle. It was published in Batltimore, New York, Massachusetts, Albany and — yes — Rochester. A quick search of digitized newspapers suggests how far, and how often, the report of a back Confederate regiment in the field, seemingly confirmed by a captured Confederate officer, made it into print:

- St. John, New Brunswick Morning Freeman, July 25, 1861, p. 4, col. 3 (Google News)

- Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser, July 22, 1861, p. 1 (Google News)

- Baltimore Sun, July 22, 1861, p. 2 (Google News)

- Lewiston, Maine Daily Evening Journal, p. 2, col. 2 (Google News)

- Springfield, Massachusetts Daily Republican, July 22, 1861, p. 4, col. 3 (GenealogyBank)

- Lowell Massachusetts Daily Citizen and News, July 22, 1861, p. 2 (GenealogyBank)

- Albany Evening Journal, July 22, 1861, p. 1. col. 6 (GenealogyBank)

- Jamestown, New York Journal, July 26, 1861, p. 2, col. 4 (GenealogyBank)

- Mineral Point, Wisconsin Tribune, July 26, 1861, p. 1, col 4 (NewspaperArchive)

- New York Daily Tribune, July 22, 1861, p. 5, col. 4 (Library of Congress)

- Moore’s Rural New Yorker, July 27, 1861, p. 6, col. 3 (Rochester Area Historic Newspapers)

As noted, these eleven citations are not an exhaustive list of papers that published this account in 1861; these are only examples that, 150 years later, survive in digitized, searchable form. The actual number of papers, large and small, across the country that repeated these short paragraphs may have counted in the dozens. Summaries based on Pryor’s account went even farther, with the British papers picking up and embellishing the claim. The Guardian was almost certainly rehashing Pryor’s account when it reported on August 7 that “Jefferson Davis was conspicuous on the field, on a white horse, in command of the centre of the army. A negro regiment fought on the same side.” The Illustrated London News went farther, claiming not only that such a unit went into action, but that “Northern troops found themselves opposed to a regiment of coloured men who fought with no want of zeal against them.”

I have no idea who “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor” was; the 19th Mississippi had two Pryors, neither of which appear to be the man mentioned in the story. But who he was is less important here than assessing the reliability of his claims. I asked Harry Smeltzer of Bull Runnings for a quick assessment of Pryor’s report, as printed in the papers. Harry agreed, so long as I would indemnify him against getting dragged into the black Confederate discussion. (Done.) The Confederate numbers quoted are way off, he said, but then “numbers were wildly overstated by both sides, each being convinced they were outnumbered.” He continued:

OK – lots of [redacted barnyard term] in there, of course. The Federals did not move again on Manassas.

No 19th Mississippi at the battle: 2nd, 11th 13th, 17th, 18th. Last two were with Jones at McLean’s Ford. 2nd & 11th were with Bee and 13th with Early, so those three could have been where the 2nd Wisc was at some point. Pryor would have to have been very lost to wander from Jones to 2nd Wisc. Best bet to me is the 2nd or 11th. . . .

[Jeff Davis] arrived shortly after the fighting had stopped, during the retreat. . . .

Whoever “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor” may have been, his claims about the battle and the Confederate army are a mess. Even allowing for the fog of war and the reality that no one, even the generals themselves, has a full and accurate picture of the fight in real time, Pryor’s claims are dubious and unreliable. It’s impossible to know, at this remove, what Pryor said on the battlefield, but what he’s quoted as saying in the newspaper is pretty worthless.

We’ll likely never know what caused Douglass to make his claim that the Confederacy had put African American soldiers on the field at Manassas. He may have heard about the battle from someone present, though Douglass’ passage doesn’t suggest that. He may well have followed the debate in the Congressional Globe, but at the same time he almost certainly was aware of the claims of “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor,” printed in at least two papers likely to have crossed his cluttered desk in Rochester, Horace Greeley’s New York Daily Tribune and one of the local sheets, Moore’s Rural New Yorker. The presence of black men in Confederate uniform was an oft-repeated rumor that the time, and Douglass very likely saw “Brigadier Quartermaster Pryor’s” dubious account as further confirmation. Even an esteemed author like Frederick Douglass can only be a reliable as the material he has to work with.

_________________

Image: Issue of Douglass’ Monthly newspaper, via Division of Rare & Manuscript Collections, Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University.

Were Cooks Enlisted in the Confederate Army?

In a recent post, I took to task a well-known researcher on the subject of black Confederate soldiers, for her misrepresenting the case of a private in the 21st U.S. Colored Infantry, who upon enlistment was taken out of the ranks and assigned to work as a company cook. Although his subsequent disability discharge paperwork makes clear that the 42-year-old private’s reassignment as a cook was because “he has never been able to drill, or to march with the company, or do any military or fatigue duty,” the researcher stated, incorrectly, that he had enlisted specifically as a cook, and she then went on to argue that, because that man was a soldier in the Union army, all cooks in the Confederate army were soldiers, too.

In a recent post, I took to task a well-known researcher on the subject of black Confederate soldiers, for her misrepresenting the case of a private in the 21st U.S. Colored Infantry, who upon enlistment was taken out of the ranks and assigned to work as a company cook. Although his subsequent disability discharge paperwork makes clear that the 42-year-old private’s reassignment as a cook was because “he has never been able to drill, or to march with the company, or do any military or fatigue duty,” the researcher stated, incorrectly, that he had enlisted specifically as a cook, and she then went on to argue that, because that man was a soldier in the Union army, all cooks in the Confederate army were soldiers, too.

In making her case, the researcher compared the USCT soldier to William H. Dove, an African American man who appears on the rolls of the 5th North Carolina Cavalry. In the comments that followed, one of my regular readers made a blunt point: “But if they were enlisted they were soldiers. William Dove, Cook, Co. E, 5th NC Cavalry was a soldier.”

That’s an entirely reasonable position to take. It’s simple, it’s logical, and it’s easily applied as a standard. But it also raises the question: were the cooks who accompanied and served the Confederate army actually enlisted?

[Before proceeding, let me clarify that in this post, I’m discussing men who worked full-time as unit cooks, not individual soldiers who took turns acting as “cook” for their messes.]

There are several ways to approach this question. A reasonable place to start would be the actual regulations for the Confederate States Army. Several editions of the regs were published from 1861 through 1864; I haven’t found an 1865 edition. But the wording in different editions of the regulations is so similar that I’ll take the mid-war edition of the Regulations for the Army of the Confederate States (“the only correct edition”), published in 1863, as representative. It also happens to be the edition in effect at the time William Dove joined the 5th North Carolina as a cook in December 1863.

While the Regulations go into considerable detail on the provision of cooks in military hospitals (see here and here and here), when it comes to field formations it’s almost completely silent. Article XLVI on the Confederate recruiting service, makes no mention of enlisting cooks in eighteen pages. Elsewhere the regulations are unclear, if not contradictory. They state, for example, that “as soldiers are expected to preserve, distribute, and cook their own subsistence, the hire of citizens for any of these duties is not allowed, except in extreme cases,” but elsewhere provide that each company would be allowed four cooks (as well as four washer-women) for distribution of rations, and that cooks of units embarked on military transports were exempted from one of the two required inspection formations daily. There were other arrangements, as well; in the closing days of the war, for example, Nathan Bedford Forrest issued general orders reorganizing and consolidating his command, instructing that “there will be allowed a negro cook to every mess of ten” troopers, a proportion more than double that allowed under army regulations for infantry units. There’s little clarity to be found in existing army policy and procedure. While the Regulations acknowledge the presence of, and make explicit allowance for, cooks in the Army, there’s no indication that the Richmond intended those men to be formally enlisted.

But regulations are one thing; practice is often another. Anyone who’s been part of a large organization knows that there’s often a wide divergence between policy — what’s supposed to be done — and what actually is done in the day-to-day operations of the group. Is there a way to get a rough estimate of how common it was for the Confederate Army to formally enlist cooks? Yes, there is.

The Data. The National Park Service developed its Civil War Soldiers & Sailors System (CWSSS), an online database, to include essential facts about servicemen who served on both sides during the war. It contains about 6.3 million names, which are themselves drawn from compiled service records (CSRs) held at the National Archives. CSRs are not regimental muster rolls, but are abstracted from them; long before they were transferred to NARA, file clerks at the War Department meticulously copied each man’s name, on each roll, to a long card along with other information about him drawn from the rolls. These, along with other paperwork — hospitalization records, receipts, requisitions, discharge papers and the like, were combined and filed in small folders, one for each man. (These are the documents, microfilmed and digitized, that are now available via commercial services like Footnote.) Because any given man might have his name listed differently on several documents, and because the clerks doing the work had no practical way to sort them out, there many duplications of names, alternate spellings, and so on. The end result of all this is that, while the CSRs and NPS database derived from them are not “clean” data — due in large part to the duplication of names — the CWSSS is a relatively comprehensive database.

It’s true that many contemporary records were lost, particularly Confederate unit records from the last months of the war, and so are not reflected in either the CSRs at the National Archives or the CWSSS. But while this poses a problem for researchers looking for a specific individual, it’s less a concern for the simple analysis offered here, which focuses on extant records only, to see how often cooks are reflected in the muster rolls of Confederate units. The fields available in the CWSSS include “Soldier’s Rank_In” and “Soldier’s Rank_Out,” which allow the researcher to quickly scroll through the names listed for each regiment, to identify men with the listing of “Cook” in either field.

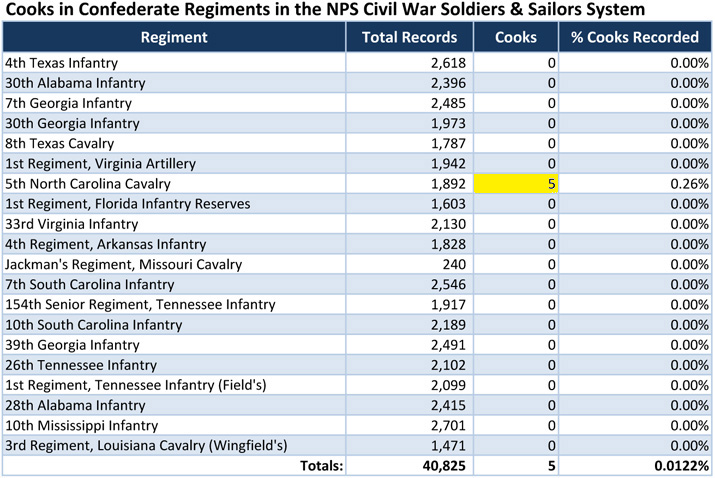

Methods. I selected twenty Confederate regiments to look for men who appear in the CWSSS as “Cook,” either as their initial or final rank. Several regiments were ones that my own relatives had served in; others were suggested by readers of this blog. I tossed in a couple of other regiments on a whim, including the parent regiment of the famous companies of the (supposedly integrated) Richmond Howitzers, just for fun. I also included William Dove’s 5th North Carolina Cavalry, which was the only unit I knew going into the project that had at least one entry for a cook — the number of cooks in the other nineteen regiments were unknown to me at the time I began going through the lists.

Results. There are five entries for cooks, in 40,825 names total — one one-hundredth of one percent, as opposed to a figure between 3% and 5%, based on the organization outlined by army regs, at four cooks per company, or 40-45 cooks per infantry regiment at full strength. It’s possible I missed a few cooks in skimming through the regiments listed here, but even a dozen more men would barely move the needle. But if this sampling is broadly indicative of the Confederate army as a whole — and I don’t know why it wouldn’t be — then the larger situation is clear, that cooks were almost never carried on the rolls as enlisted men. Certainly there are other examples than the five men in the 5th North Carolina Cavalry, but even if there are scores more, they much represent a very tiny fraction of the thousands of men who served as army cooks at one time or another during the war.

So why, in this sample of 20 regiments, are there only a handful of examples clustered in the 5th North Carolina Cavalry? The answer may lie in those five men’s CSRs — four of the five were carried on the rolls of Company E of that regiment, and were placed there by Captain Thomas W. Harris. (The fifth man, like Hannibal Alexander, has a CSR that reflects only his parole from a Federal prison camp; his presence with the 5th North Carolina is not recorded.) Why did Captain Harris, in particular, formally enter these men on his company’s rolls when the other officers of the regiment did not? It’s apparent that these men were not themselves cavalry troopers; each one’s CSR carries the notation, like William Dove’s, “has no horse.” Did he he misunderstand the regulations, or common practice, or was there a specific reason? Whatever the answer, Harris’ decision to enter these men on the roster of Company E clearly stands in stark contrast to common practice; it’s very much a one-off situation.

There’s no question that Confederate cooks, body servants and others considered non-combatant did sometimes find their way into action. Richard Quarls, for example, is reputed to have picked up his master’s rifle when the man was hit, and defended him until he could be removed from the field. There are many such anecdotes, but it’s useful to keep in mind why such incidents were recorded in the first place — because they were out of the ordinary, and beyond the expected scope of those mens’ stations.

But against this there are at least as many accounts from Confederate soldiers of African American cooks and servants that gently mock them for supposed dumb indifference to enemy fire, or for their alleged comical cowardice. Val Giles, describing how his company of the 4th Texas Infantry was pinned down at the foot of Little Round Top after the previous day’s assault, noted that “Uncle” John Price brought up the company’s rations under fire, and promptly lay down behind a boulder and went to sleep, even as Yankee Minié balls splatted against the rocks, “making lead prints half as big as a saucer.” The Rev. J. N. Crain, told of an incident in an 1898 issue of the Confederate Veteran, about an outdoor religious service held after the Battle of Chickamauga:

In the early part of the service a battery belonging to “out friends the enemy” sent a shell, which exploded some two or three hundred yards below our position. A negro [sic.] cook, who had his belongings just outside of the place occupied by the congregation, put them over his shoulder with the significant remark: “this nigger is gwine to git out o’ here.” That caused a ripple of laughter in the congregation, but all sat still. During the long prayer of our service another shell came much nearer. When the prayer was finished and the chaplain’s eyes were opened he saw that the congregation, with the exception of five or six, had followed the cook.

African American cooks and servants were often remembered in this way, as a sort of comic relief, and even so august a personage as Robert E. Lee joined in humor at the expense of the servants’ dignity. John Brown Gordon, a corps commander in the Army of Northern Virginia and later the first Commander of the United Confederate Veterans, wrote in his memoir that

General Lee used to tell with decided relish of the old negro [sic.] (a cook of one of his officers) who called to see him at his headquarters. He was shown into the general’s presence, and, pulling off his hat, he said, “General Lee, I been wanting to see you a long time. I ‘m a soldier.”

“Ah? To what army do you belong—to the Union army or to the Southern army ?”

“Oh, general, I belong to your army.”

“Well, have you been shot ?”

“No, sir; I ain’t been shot yet.”

“How is that? Nearly all of our men get shot.”

“Why, general, I ain’t been shot ’cause I stays back whar de generals stay.”

This anecdote reinforces Gordon’s (and Lee’s) dismissal of the idea that the service of black men like the cook should be considered soldiers; what made the story amusing to both generals is that the man’s claim to status as a soldier was, to their thinking, preposterous on its face, and (according to Gordon) thought by Lee himself to be worthy of telling and re-telling.

These men were also sometimes the direct target of ribald and occasionally dangerous pranks by bored soldiers, in ways that fellow soldiers likely would not be. Clement Saussy, a private in Wheaton’s Light Battery (Chatham Artillery), told of one such incident in a 1906 issue of the Confederate Veteran:

Of course we had to have some amusement as the time passed, and I decided to have some fun with a negro [sic.] named Joe, who was cook for the “Jeff Davis Mess.” He was ignorant and superstitious. I told him the Yankees were going to shell our camp. He lived in a small hut near the mess house, and every night held a solo prayer meeting. While on picket duty at the ordnance stores I had obtained the powder from an eight-inch shell, and then had removed the fuse. The powder I took to camp and made a bomb out of an old canteen, placed it behind Joe’s house, and lighted the fuse. A number of the boys stood by with bricks, so that when the bomb exploded they were to pelt the house. The fuse burned too slow, and one of the boys said: “Saussy, go look at the fuse.” I crept up. peeped in, and said : “It’s burning all right.” “Blow it,” my companion said, and, without thinking, I blew it and it blew me, for off it went, about two pounds of powder close to my face, blinding my sight for the instant and burning my eyebrows and eyelashes. I fell over, but this was not all. The boys began the brickbat bombardment, and I received my full share of the bricks. Joe was badly scared and ran from the hut. I was temporarily put out of service, but it was fun all the same.

Saussy doesn’t say whether Joe also found being scared and pelted with brickbats “fun all the same.”

These are not respectful accounts; these are not the way one speaks of, or remembers, a peer. Anecdotes like these make clear that, while they might occasionally be praised for noteworthy actions, more commonly army cooks were mocked and derided, the butt of jokes and pranks at their expense. (One should note that their treatment in the Union army was probably little better.)

While it does appear that at least a handful of African American men were carried on the rolls of Confederate regiments, it’s equally clear that the practice was not only not common, but exceedingly rare compared to their actual numbers. Formal regulation, personnel records from the National Archives, and anecdotal evidence all make clear that, while Confederate cooks were an indispensable part of the army, and part of soldiers’ daily lives, they were almost never formally enlisted or carried on military rolls. As a general rule with (it seems) very few exceptions, cooks in the Confederate were not enlisted, and though part of the army, were legally, socially and operationally fundamentally different from the privates, corporals and lieutenants they served.

____________

Image: “Dick, sketched on the 6th of May, on return to camp,” by Edwin Forbes. A Union Army cook from 1863. Library of Congress.

18 comments