Famous “Negro Cooks Regiment” Found — In My Own Backyard!

More crackerjack analysis from the leading online researcher of “black Confederates”:

Captain P.P. Brotherson’s Confederate Officers record states eleven (11) blacks served with the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery in the “Negro Cooks Regiment.” This annotation can be viewed on footnote.com. See the third line on the left. Also, the record is cataloged in the National Archives Catalog ID 586957 and microfilm number M331 under “Confederate General and Staff Officers, and Nonregimental Enlisted Men.”

Could this be one of the types of regiments many Confederate historians have documented as part of Confederate History?

Here’s the document in question:

Note that the critical phrase “Negro Cooks Regiment,” as quoted by the researcher, does not appear in the document, which is a routine statement of rations drawn for conscripted laborers. The actual text reads, “Provision for Eleven Negroes Employed in the Quarter Masters department Cooks Regt Heavy Artillery at Galveston Texas for ten days commencing on the 11th day of May 1864 & Ending on the 20th of May 1864.” There’s a similar document in the same collection, covering the period May 21 to 31, as well.

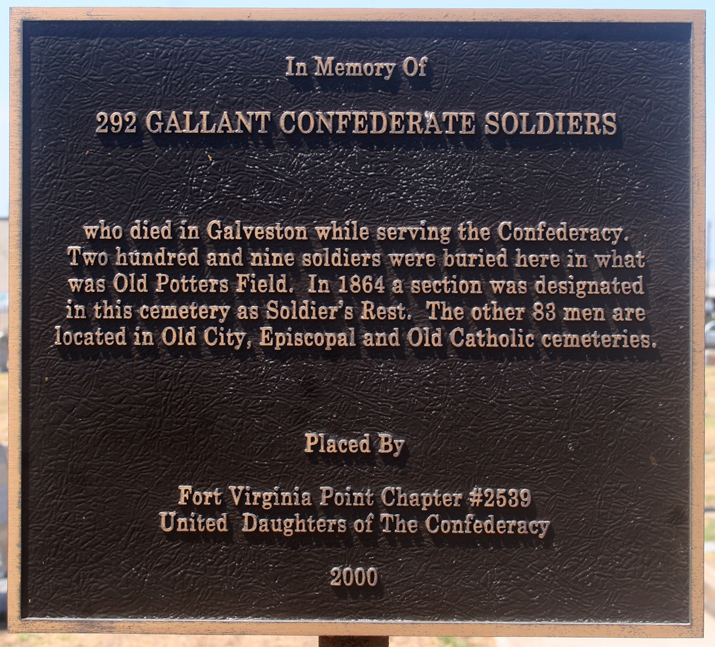

“Cook’s Regiment” is an alternate name for the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery. Like many Civil War regiments, it was widely known and referred to by the name of its commanding officer, Colonel Joseph Jarvis Cook (right). The regiment, formed from a pre-war militia unit, served at Galveston through most of the war, manning the artillery batteries around the island. The African Americans referred to in the document, attached to the regiment’s quartermaster, were likely used in maintaining the trenchwork and fortifications occupied by the regiment, or moving supplies and munitions between them. After the war, the former members of the regiment reorganized themselves as a sort of unofficial militia unit again, which eventually morphed into a social club. The Galveston Artillery Club exists right down to the present day. (Highly recommended for lunch, if you can score an invite.)

“Cook’s Regiment” is an alternate name for the 1st Texas Heavy Artillery. Like many Civil War regiments, it was widely known and referred to by the name of its commanding officer, Colonel Joseph Jarvis Cook (right). The regiment, formed from a pre-war militia unit, served at Galveston through most of the war, manning the artillery batteries around the island. The African Americans referred to in the document, attached to the regiment’s quartermaster, were likely used in maintaining the trenchwork and fortifications occupied by the regiment, or moving supplies and munitions between them. After the war, the former members of the regiment reorganized themselves as a sort of unofficial militia unit again, which eventually morphed into a social club. The Galveston Artillery Club exists right down to the present day. (Highly recommended for lunch, if you can score an invite.)

I wouldn’t expect most people, even Civil War buffs, to know what “Cook’s Regiment” was off the top of their heads, but it’s quite clear from the original document that it’s an artillery unit, as opposed to a regiment of cooks. The key phrasing quoted, “Negro Cooks Regiment,” is an outright fabrication. And 30 seconds with a search engine would’ve clarified the situation immediately.

Or maybe doing minimal due diligence like that is just a trick used by politically-correct, revisionist “pundits” like myself.

Forget interpretation. Forget analysis. Forget trying to understand the document within the context of the time and place it was written; these people don’t even seem capable of reading the documents they cite. This particular researcher has a track record of misreading documents, and drawing conclusions based on that misreading. A few weeks ago she claimed that the record of one African American, attached to a cavalry regiment, carried the notation, “has no home,” and went on to argue this showed special commitment to the Confederate cause: “with no home, [he] was not phycially [sic.] bound to the south. However, he stayed and served the Confederate States Army.” The actual notation, repeated again and again on cards throughout his CSR, was “has no horse.”

On another occasion, she quoted from a book on Camp Douglas, supposedly to show that a black servant held there had not been released as a former slave, but was held as a prisoner because the Federal authorities had determined that he was a bona fide soldier. This, she argued, was evidence that enslaved personal servants were deemed Confederate soldiers by the Union military. Unfortunately, the very next lines of the book she was quoting from verify that the prison camp did, after months of dragging their heels, determine the man was a slave, and released him on exactly those grounds by order of the Secretary of War.

And now, an entire regiment of “Negro cooks,” right here in my own home town. How did I miss that one? 😉

__________

Image: Order for the evacuation of Galveston, October 1862, signed by Col. Joseph Jarvis Cook, commanding Confederate troops on the island. Rosenberg Library, Galveston.

GALVESTON, Wednesday, Feb. 17.

GALVESTON, Wednesday, Feb. 17.

4 comments