Discovering the Civil War at the Houston Museum of Natural Science

The Discovering the Civil War exhibition at its previous venue, the Henry Ford Museum. Via here.

On Saturday the fam and I took the afternoon to visit the exhibition, Discovering the Civil War, currently at the Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS). The exhibit runs through April 29, and is produced by the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration and the Foundation for the National Archives. It’s hard to do a compelling museum exhibition based almost entirely on documents and images; people want to see stuff, and that’s understandable. This particular exhibit succeeds pretty well, I think, in part because the documents they’ve included are genuinely compelling, and do a very good job of telling the story. The exhibition includes, for example, facsimiles of the 1861 Corwin Amendment, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the original text of the 13th Amendment ending slavery in the United States, bearing the signatures of Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, Vice President and President of the Senate Hannibal Hamlin, and President Lincoln. (The original holograph copy of the Emancipation Proclamation will be on exhibit on February 16-21.)

One of the common complaints among Southron Heritage™ folks is that the limitations of the Emancipation Proclamation “isn’t taught in school” or “you never hear about that” or some such. So I almost laughed out loud when, not a minute after stepping into the first section of the exhibit, an HMNS guide stepped up to explain to us and others some of the featured documents in the show, and drawing very careful distinctions between the limited, wartime scope of the EP, and the permanent, legislative accomplishment of the 13th Amendment.

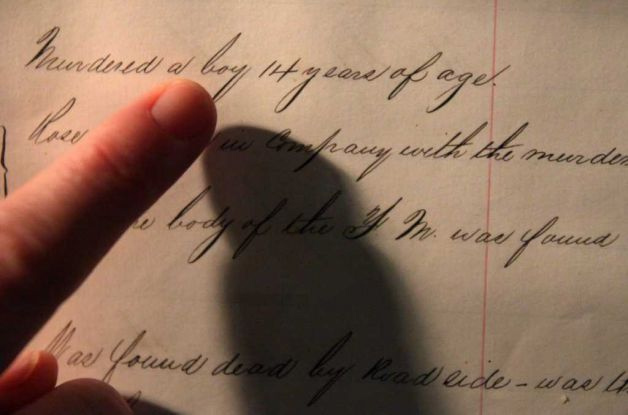

A curator at the Houston Museum of Natural Science points to entries in the Freedmen’s Bureau “Texas Record of Criminal Offences” from 1868. Photo: Mayra Beltran / © 2011 Houston Chronicle

The exhibit doesn’t only cover the war years; it goes back into the decades-long tensions over slavery and other sectional issues that led to the war, and devotes considerable space to the postwar period, including the creation of veterans’ groups like the GAR and UCV, reunions, monuments, and so on. It was in the area on the Reconstruction period that I came across a particularly chilling artifact, a big ledger in which the officers of the Freedmens’ Bureau in East Texas recorded assaults and murders of African Americans, attacks believed to be part of the terror campaign led by the Ku Klux Klan and allied groups to limit the new citizens’ participation in the electoral process and to intimidate anyone who challenged the pre-war power structure. The pages on display opened to 1868, the year such depredation came to a climax, in anticipation of that year’s general election. The the neatly-penned columns of names of the victims, alleged perpetrators, and nature of the crime — almost all listed simply as “homicide” — were deeply unsettling.

There is some hands-on material, including a section where visitors are asked to view an illustration from a wartime patent application, and then guess what the object is. The HMNS has also set up a kids’ discovery room, about halfway through, where young visitors can try on period costumes and work puzzles involved Civil War-era cryptography.

The museum has also appended a display at the end of the NARA exhibit, focusing on Texas during the war, with lots of arms and other artifacts from local units. These are, I believe, materials from the John L. Nau III, Civil War Collection. The recent recovery of artifacts from the wreck of the U.S.S. Westfield is discussed, as well.

Finally, there’s an extensive series of public presentations being given on different aspects of the conflict, including one on the recovery of the U.S.S. Westfield artifacts on March 27, and one by myself on March 27, “Patriots for Profit – The Blockade Runners of the Confederacy.” Hope to see y’all there.

_______________

“Having finished life’s duties, they rest.”

About a year ago, I put up a post about Thomas Tobe, a free African American man from South Carolina who was conscripted to work at General Hospital No. 1 in Columbia, South Carolina during the summer of 1864. Tobe later received a state pension based on service he claimed with Company G of the 7th South Carolina Cavalry, Holcombe’s Legion. This latter claim is problematic, as there are no contemporary records verifying his attachment to that unit. Critical details are missing from the pension application, such as Tobe’s attested rank, and the men who swore as witnesses to his service were from different regiments. Tobe may well have been attached to that unit, perhaps as a cook, a personal servant or in a similar capacity, but there’s no direct evidence that he served as a trooper.

At the time of the post, I understood that Thomas and his wife Elizabeth were buried in the cemetery at Fairview Baptist Church, near Newberry, South Carolina. Recently I received confirmation of this from Kevin Dietrich, a member of the area SCV camp. Dietrich was out visiting cemeteries recently, looking for graves of persons from the Civil War era, and made a note of Tobe’s gravesite, not knowing anything else about him, just based on the dates on the stone. A Google search on Tobe’s name led Dietrich to this blog and my post on Thomas Tobe. Mr. Dietrich has generously consented to having his recent photos of the site posted here. The marble stone Thomas and Elizabeth share carries the inscription, “having finished life’s duties, they rest.”

__________

Hey, I Know that Guy. . . .

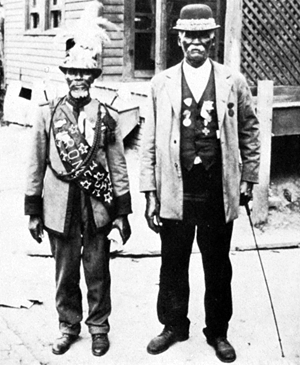

While looking for something else, I came across this photo of Steve Perry, a.k.a. “Uncle Steve Eberhart,” and another, unidentified man at a Confederate reunion in Houston, Texas. The image is undated, but I believe it to be from the time of the big United Confederate Veterans reunion at Houston in October 1920. Although Perry appeared as “Uncle Steve Eberhart” at reunion activities for more than 20 years, his costume here closely matches that worn in photographs of him like this one, appearing in a 1922 history of Rome and Floyd County, Georgia. In that book, Perry is quoted as saying about the 1920 Houston reunion,

While looking for something else, I came across this photo of Steve Perry, a.k.a. “Uncle Steve Eberhart,” and another, unidentified man at a Confederate reunion in Houston, Texas. The image is undated, but I believe it to be from the time of the big United Confederate Veterans reunion at Houston in October 1920. Although Perry appeared as “Uncle Steve Eberhart” at reunion activities for more than 20 years, his costume here closely matches that worn in photographs of him like this one, appearing in a 1922 history of Rome and Floyd County, Georgia. In that book, Perry is quoted as saying about the 1920 Houston reunion,

I want to thank the good white people of Rome for sending me to Texas to the Old Soldiers’ Reunion. I am thankful. I shall ever remain in my place, and be obedient to all the white people. I pray that the angels may guard the homes of all Rome, and the light of God shine upon them. I will now give you a rest until the reunion next year, if the Lord lets me live to see it. Your humble servant. Steve Eberhart.

As I’ve said before, such framing is painful to modern ears, but it reflects the difficult line African Americans had to tread not so many generations ago. It makes clear how these men, even as they swapped old tales and enjoyed themselves with the white veterans, were also expected to reinforce specific, stereotyped roles of African Americans in the Jim Crow South — obsequious, grateful, and non-threatening to the status quo antebellum. It’s a difficult, multi-layered dynamic that defies simple tropes of egalitarian patriotism.

_______________

Image credited to Houston Metropolitan Research Center, Houston Public Library.

Research a Mile Wide, and an Inch Deep

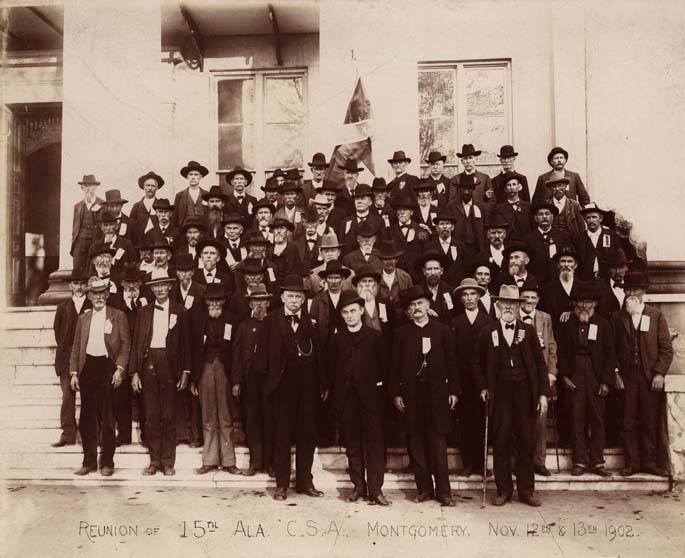

The deeply shallow “research” to prove the existence of black Confederates continues apace. This image, from the Alabama Department of Archives and History, is of men from the 15th Alabama Infantry attending a statewide Confederate veterans reunion in Montgomery, in November 1902. The 15th Alabama, many will recall, is the regiment that made repeated attempts to dislodge the Union flank on Little Round Top on the second day at Gettysburg, facing the famous 20th Maine Infantry. I believe the former commander of the 15th Alabama, William C. Oates, is the first man at left in the front row in the image, directly above the C in “C.S.A.”

The image has become a point of discussion online recently, particularly in reference to the dark-skinned man in the second-to-last row, third from the end on the right. The discussion seems to center around whether the man is African American, of mixed race, or perhaps is a white man with very dark, tanned skin. Whether he’s actually African American or not is critical, because the beginning and end of the question is whether or not a black man attended a Confederate reunion. That fact, in and of itself, is apparently supposed to tell us all we need to know about African Americans and the Confederacy.

Of course, it doesn’t.

Warning: The following includes historical quotes that use offensive language and themes.

Nathan Bedford Forrest Joins the Klan

Nathan Bedford Forrest is always a popular subject in Confederate heritage, but that’s never been more true than it is today. He’s frequently featured in the secular trinity of Confederate heroes, alongside Lee and Jackson. And like those two – and only those two – Forrest has achieved the modern apotheosis of Confederate fame, having his own page of t-shirts at Dixie Outfitters.

Nathan Bedford Forrest is always a popular subject in Confederate heritage, but that’s never been more true than it is today. He’s frequently featured in the secular trinity of Confederate heroes, alongside Lee and Jackson. And like those two – and only those two – Forrest has achieved the modern apotheosis of Confederate fame, having his own page of t-shirts at Dixie Outfitters.

But Forrest’s defenders often hold the line at one claim, that he was a prominent figure in the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan. Even as they struggle to rationalize the Klan of that period as a necessary counter against the supposed excesses of the Union League and other northern influences, they usually deny any involvement of Forrest in the Klan’s organizing or activities, except for the odd claim that Forrest, despite having no authority or connection to the group, successfully ordered them to stand down in 1869.

So did Forrest really join the Ku Klux Klan? Yes, he did. Was he really Grand Wizard of the group? Yes, he was. How do we know this? Because the old klansmen who were there tell us so.

Steve Perry and “Uncle Steve Eberhart”

Steve Perry, a.k.a. “Uncle Steve Eberhart,” c. 1934.

As many readers will know, African Americans were a fairly common sight at Confederate soldiers’ reunions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Today, some view photographs from these reunions as evidence that the black men shown were considered full and equal soldiers by the white veterans. While there was undoubtedly plenty of reminiscing and genuine bonhomie between the white and black men at such events, a closer look at contemporary descriptions from the time reveals that there were crucial differences in the way each group was viewed and treated that subtly but firmly reinforced the long-established racial order in the South. Simply put, even after the passage of forty, fifty or sixty years, former slaves and body servants were still expected to keep their place and defer to the attitudes that prevailed in the Jim Crow South.

Warning: The following includes extensive historical quotes that use offensive language and themes.

General Stephen D. Lee Disses Black Confederates

One area that the advocates of black Confederate soldiers (BCS) are mostly silent on is the stated attitudes and opinions of actual Confederate leaders who lived and fought through the war of 1861-65. Those views comprise a hard, bitter lump of historical reality that must surely cause indigestion for BCS advocates, given that the “Confed cred” of those men is unassailable. We’ve seen, for example, how both Howell Cobb and his fellow Georgian, Governor Joseph Brown, viewed the prospect of arming slaves with revulsion, and saw it as a betrayal of everything the Confederacy stood for. We’ve seen how Kirby Smith asserted that the Confederacy should “go to the grave before we enlist the negro [sic.].” And we’ve seen how, according to John Brown Gordon, even the venerable Robert E. Lee himself liked to humor his colleagues with an anecdote mocking the pretensions of an African American cook to being a soldier. It’s ugly, unpleasant stuff, but it’s right there, and ignoring it won’t make it go away.

Stephen Dill Lee (right, 1833-1908) was a Confederate general — the youngest of the South’s lieutenant generals, in fact — who after the war went on to a varied career as an author, a legislator, and educator. He was very active in Confederate veterans’ organizations, and succeeded Gordon as Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans. In many ways, S. D. Lee was the public face of Confederate veterans, both in the North and the South. S. D. Lee is remembered today particularly for his charge to the Sons of Confederate veterans, given as part of a speech in New Orleans in 1906. Lee’s charge has been used ever since as the guiding principle of the organization, and features prominently in SCV publications, both in print and online. (Read it here, at the bottom of the page.) Indeed, the quasi-academic arm of the SCV, the Stephen Dill Lee Institute, is named in his honor.

Stephen Dill Lee (right, 1833-1908) was a Confederate general — the youngest of the South’s lieutenant generals, in fact — who after the war went on to a varied career as an author, a legislator, and educator. He was very active in Confederate veterans’ organizations, and succeeded Gordon as Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans. In many ways, S. D. Lee was the public face of Confederate veterans, both in the North and the South. S. D. Lee is remembered today particularly for his charge to the Sons of Confederate veterans, given as part of a speech in New Orleans in 1906. Lee’s charge has been used ever since as the guiding principle of the organization, and features prominently in SCV publications, both in print and online. (Read it here, at the bottom of the page.) Indeed, the quasi-academic arm of the SCV, the Stephen Dill Lee Institute, is named in his honor.

The SCV has, of course, spent a great deal of time and effort in recent years pushing the BCS meme. While lots of folks endorse or promote the idea that there were large numbers of African Americans formally enlisted and armed in the Confederate ranks, the SCV is (through its state divisions and local camps) by far the largest single proponent of the idea. Much of this is simply based on careless research or misunderstood documents, but it also results in cases of over-reach that should be genuinely embarrassing to the group, including retroactive assignment of name and rank to men who never claimed such, or the creation of an entire faux cemetery of black Confederates, without a single actual interment there.

So it comes with considerable irony to learn that around the same time the SCV was founded, S. D. Lee was telling reporters at a Confederate reunion what he thought of as a funny anecdote, complete with cartoonish African American “dialect,” that relies on ugly racial stereotypes about African Americans’ courage under fire and instinct for self-preservation for its “humor.” From the Idaho Statesman, January 25, 1896 (warning: offensive language and themes follow):

Looking In From the Outside, Black Confederates Edition

Leslie Madsen-Brooks, an assistant professor of history at Boise State University, has put up an essay on the online discussion over BCS. It’s interesting to see an outsider’s view of this business. For those who’ve followed the discussion for a while, it covers a lot of familiar territory, and a lot of familiar names. For folks who are new to the subject, it gives a pretty good lay of the land, and a useful introduction to the characters involved.

Leslie Madsen-Brooks, an assistant professor of history at Boise State University, has put up an essay on the online discussion over BCS. It’s interesting to see an outsider’s view of this business. For those who’ve followed the discussion for a while, it covers a lot of familiar territory, and a lot of familiar names. For folks who are new to the subject, it gives a pretty good lay of the land, and a useful introduction to the characters involved.

And boy howdy, are there some characters. 😉

h/t Kevin Levin and Brooks “Perfesser” Simpson

_______________

Image: Unidentified young soldier in Confederate uniform and Hardee hat with holstered revolver and artillery saber, Library of Congress.

Someone Is Wrong in the Newspaper!

A friend recently pointed me to a guest column in the local paper that I’d missed, challenging the idea of a sesquicentennial celebration of Juneteenth here in 2015. The writer, Robert Hart, peppers his column with “facts” that “Juneteenth proponents should know,” which are mostly wrong. You can read it here. While Hart suggests time would be better spent interviewing African Americans about segregation, which pretty much everyone agrees was a Bad Thing, I suspect he’s mainly interested in deflecting attention off onto something other than the central role of slavery in the Confederacy. His column has almost nothing to do with Juneteenth, offering instead a list of standard Southron Heritage™ talking points about various bad acts perpetrated by the Yankees.

A friend recently pointed me to a guest column in the local paper that I’d missed, challenging the idea of a sesquicentennial celebration of Juneteenth here in 2015. The writer, Robert Hart, peppers his column with “facts” that “Juneteenth proponents should know,” which are mostly wrong. You can read it here. While Hart suggests time would be better spent interviewing African Americans about segregation, which pretty much everyone agrees was a Bad Thing, I suspect he’s mainly interested in deflecting attention off onto something other than the central role of slavery in the Confederacy. His column has almost nothing to do with Juneteenth, offering instead a list of standard Southron Heritage™ talking points about various bad acts perpetrated by the Yankees.

Anyway, the Galveston County Daily News was kind enough to run a guest column of mine today, countering Hart. It’s not great writing on my part, as I found it harder that in oughter be to keep it under 500 words:

Robert Hart recently published a guest column in the GCDN (“Juneteenth proponents should know facts,” Oct. 5), on celebrating the sesquicentennial of Juneteenth in 2015. Mr. Hart’s column, unfortunately, includes a great deal of information that serves only to deflect attention from the subject. Whether or not Ulysses Grant personally owned slaves has nothing to do with the legitimacy of Juneteenth as a day of celebration.

Worse, many of the “facts” Hart includes in his column are demonstrably false. Hart says that Grant “owned slaves in Missouri and freed them only when he had to.” In fact, Grant is known to have owned a single slave during his lifetime, a man named William Jones, possibly received from his father-in-law, probably in 1858. Grant formally manumitted (freed) Jones in March 1859.[1]

Hart claims that Robert E. Lee “freed his slaves 10 years before the war.” Not true. As biographer Elizabeth Brown Pryor discovered in going through the general’s papers, Lee personally owned slaves at least as late as 1852, considered buying more shortly before the war began, and used slaves as personal servants throughout the war itself. More important, from late 1857 onward he was acting as executor of his father-in-law’s estate at Arlington House, where he ruled with a far stricter hand than the Custises ever had. There’s credible evidence that he personally supervised the whipping of runaway Arlington slaves in 1859.[2] Lee did not formally manumit these slaves until the end of 1862.[3]

Hart continues, saying that “the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t free a single slave when it was issued.” Again, not true. As Eric Foner points out in his recent, Pulitzer Prize-winning book on Lincoln and emancipation, the order freed tens of thousands of slaves immediately in Union-occupied areas, and firmly established permanent emancipation as official war policy.[4] The Emancipation Proclamation made the Union Army a rolling, blue tide of emancipation. More than any battlefield victory, the Emancipation Proclamation doomed the Confederacy.

Hart argues that slavery in the United States ended with the passage of the 13thAmendment, but meaningful emancipation occurred over decades, and slaves themselves often made it happen. Some “stole themselves” from their masters. Tens of thousands of former slaves took up arms to free their kindred as part of the Union Army’s famed U.S. Colored Troops. Many more were emancipated (like those in Texas) when the Federal army arrived to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation.

Emancipation and the end of slavery are worth celebrating – not just for African Americans, but for all Americans who value liberty and freedom. Every date on the calendar is the anniversary of some small piece of that story, but some dates carry more significance than others. For both practical and symbolic reasons, June 19 is the best choice for Galveston, for Texas, and for the nation.

[1] Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822‐1865 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 71-72.

[2] Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters (London: Penguin, 2007), 270-73.

[3] Emory M. Thomas, Robert E. Lee: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1995), 273.

[4] Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2010), 243.

Of course, h/t to Bob Pollock, who continues to do the bloggy knowledge on Grant.

___________

“Durante vita”

A number of bloggers put up posts in anticipation of tonight’s History Detectives episode on the famous tintype image of Andrew Chandler and Silas Chandler. I was struck by two things watching the episode. First, this quote from Chandler Battaile, great-great-grandson of Andrew Chandler, on discovering that much of what he’d always understood to be true is contradicted by contemporary evidence:

I think it’s interesting to understand the place of stories in family histories. Obviously, the story that we’ve shared is one that is very comfortable, and comforting to believe. But without documentary evidence, it is a story. Our families’ histories have been, and will always be, deeply intertwined and evolving with the times.

That strikes me as a remarkably self-aware statement. I’ve found in my own family’s history cases where cherished family stories don’t stand up well to close examination in bright sunlight. But I think in the end, one is better for going through that process.

The second thing is the mention by Mary Francis Berry, that Mississippi law did not allow the manumission of slaves at the time of the Civil War. This is significant, because part of the Chandler oral tradition is that Silas had been freed at (or soon before) the beginning of the war, and went off with Andrew into the 44th Mississippi Infantry as a free man. While I wasn’t familiar with the Mississippi law, it’s not in the least surprising that this provision would be so. In my own state, it wasn’t just a law, it was actually written into the 1861 Texas Constitution, adopted immediately after the state’s secession. Under Article VIII, Slaves:

Sec. 1. The Legislature shall have no power to pass laws for the emancipation of slaves.

Sec. 2. No citizen, or other person residing in this State shall have power by deed, or will, to take effect in this State, or out of it, in any manner whatsoever, directly or indirectly, to emancipate his slave or slaves.

Or as Professor Berry put it, referring to Mississippi, the “law made slaves, slaves for life: durante vita.”

Antebellum Texas was not a welcoming or easy place for free African Americans; it’s not surprising that in the decade 1850-1860, while the slave population of Texas more than tripled (58,161 to 182,566), the number of free blacks in the state actually declined, from 397 to 355 — not even enough to fill a typical middle school auditorium.

_______________

Image: Andrew Chandler (l.) and Silas Chandler, c. 1861, via the Toledo Blade.

3 comments