Return Forrest to Elmwood Cemetery

This old post from the summer of 2015 seems relevant this morning.

Last week Memphis Mayor A. C. Wharton called for the remains of Nathan Bedford Forrest, his wife, and the monument that stands above them, to be returned to the city’s Elmwood Cemetery. This move is not unexpected, as monument and the park surrounding it — renamed Health Sciences Park in 2013 — have been contentious in the city of Memphis for a long time now.

This call for Forrest’s return to Elmwood comes, of course, in the wake of several states taking action to remove or end official display of Confederate iconography, from flags to specialty license plates to statues. While I think we, as southerners, need to catch our breath and think a little more deliberately when it comes to monuments of long-standing, there is actually a strong and affirmative case — a pro-Forrest case, if you will — when it comes to the site in Memphis. I’ve communicated with several people who have been interested in Forrest for a long time, and know his story well. They point out that he and his wife, Mary Ann Montgomery Forrest, were originally interred at Elmwood, and it was not until the early 20th century, three decades after the general’s death, that their remains were moved to a central park downtown. It’s a case, in many respects, like that of Robert E. Lee at Washington College, now Washington and Lee University, where a later generation decided they knew better than the general himself what he wanted.

At Elmwood, he and Mary Ann would lie again among twelve hundred other Confederate soldiers. (Perhaps it’s not mere coincidence that the statue’s bronze gaze has been fixed on Elmwood all these years.) Besides which, a transfer of Forrest’s remains and re-interment a mile away at Elmwood would give the heritage folks the opportunity for a procession and pageantry the likes of which haven’t been seen since the burial of the H. L. Hunley crew at Charleston in 2004. Lord knows, to so many of Forrest’s fans practicing history consists mainly of dressing up and solemnly parading with Confederate flags. It’s a win for all concerned — for the Forrests, who apparently preferred being at Elmwood; for the city of Memphis that, rightly or wrongly, wants to be done with what used to be known as Forrest Park; and for the heritage crowd that, with a little nudging, can undoubtedly be convinced that a move is actually the right and proper thing to do. A recent Tennessee law would seem to prohibit moving Forrest and the monument, but with everyone on board with it, I’m sure enabling legislation in Nashville is a forgone conclusion.

Confederate graves at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis. Forrest should be here, too.

The specific circumstances of the Forrest case make that call easy; the case for moving, or removing, other Confederate monuments is more difficult, and requires more deliberation. Speaking for myself, I’m ambivalent about it. While I adamantly support the authority of local governments to make these decisions, I’m not sure that a reflexive decision to remove them is always the best way of addressing the problems we all face together. Monuments are not “history,” as some folks seem to believe, but they are are historic artifacts in their own right, and like a regimental flag or a dress or a letter, they can tell us a great deal about the people who created them, and the efforts they went to to craft and tell a particular story. In 2015 it would be hard to find someone who would unequivocally embrace the message of the “faithful slaves” monument in South Carolina, but it can’t be beat as documentation of the way some white South Carolinians saw the conflict thirty years after its end, and wanted others to, as well. (Maybe York County could put a sign next to it with an arrow saying, “no, they really believed this sh1t!”)

I’ve written before about the Dick Dowling monument in Houston (right). It honors Dowling for his command of Confederate artillerymen at the Battle of Sabine Pass in 1863, but from its dedication in 1905, it was a rallying point for Houston’s Irish community, many of whom came after the war. (It was sponsored, in large part, by the Ancient Order of Hibernians.) Certainly today, as I learned firsthand, the emphasis at the annual ceremony there is much more Irish in character than Confederate. It means a great deal to those folks, many of whose Irish ancestors’ arrival in this country postdates the Civil War by decades. They have no personal connection to the war or to the Confederacy, yet the Dowling monument nonetheless serves as a common bond among them irrespective of the uniform worn by the marble figure at the top. It really would be a shame to lose that.

I’ve written before about the Dick Dowling monument in Houston (right). It honors Dowling for his command of Confederate artillerymen at the Battle of Sabine Pass in 1863, but from its dedication in 1905, it was a rallying point for Houston’s Irish community, many of whom came after the war. (It was sponsored, in large part, by the Ancient Order of Hibernians.) Certainly today, as I learned firsthand, the emphasis at the annual ceremony there is much more Irish in character than Confederate. It means a great deal to those folks, many of whose Irish ancestors’ arrival in this country postdates the Civil War by decades. They have no personal connection to the war or to the Confederacy, yet the Dowling monument nonetheless serves as a common bond among them irrespective of the uniform worn by the marble figure at the top. It really would be a shame to lose that.

I think we need to be done, done, with governmental sanction of the Confederacy, and particularly public-property displays that look suspiciously like pronouncements of Confederate sovereignty. The time for that ended approximately 150 years ago. But wholesale scrubbing of the landscape doesn’t really help, either, if the goal is to have a more honest discussion about race and the history of this country. I’m all for having that discussion, but experience tells me that it probably won’t happen. It’s much easier to score points by railing against easy and inanimate targets.

_________

Forrest monument image via PorterBriggs.com. Elmwood Cemetery image via ElmwoodCemetery.org.

“I will pay more than any other person for No. 1 Negroes”

A follow-up to my post yesterday on Charleston, and what seemed to me at the time to be a purely gratuitous inclusion of Nathan Bedford Forrest in the section on slave traders.

A follow-up to my post yesterday on Charleston, and what seemed to me at the time to be a purely gratuitous inclusion of Nathan Bedford Forrest in the section on slave traders.

It turns out that, as a colleague suggested yesterday, that Forrest did indeed make use of the slave market in Charleston to provide the “stock” he would later sell in Memphis and New Orleans. And he was not making an isolated purchase here or there; he was buying on a large scale. Charleston Courier, March 1, 1860, p. 2:

So there it is — even in South Carolina, where there were substantially more enslaved persons in 1860 than free, Nathan Bedford Forrest was a big wheel in the domestic slave trade. If Forrest had lived in South Carolina himself, the 500 slaves he sought to purchase there would have made him one of the largest slaveholders in that state. The inclusion of Forrest in the museum exhibit certainly makes sense now, but it’s unfortunate that Forrest’s role in the Charleston slave market isn’t explained clearly.

______

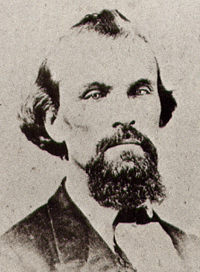

Prewar image of Forrest via Mississippi Confederates blog.

“My remains shall rest with those of brave men”

My blogging colleague Rob Baker recently passed along a link to this transcript of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s will:

FIRST I commit my body after death to my family and friends with the request that it may be entered among the Confederate dead in the Elmwood Cemetery near the City of Memphis, it being my desire that my remains shall rest with those of the brave men, men who were my comrades in war and shared with me the danger and peril of battle fields fighting in a cause we believed it our duty to uphold and maintain.

Return Nathan Bedford and Mary Ann Forrest to Elmwood. It’s the right thing to do.

___________

Return Forrest to Elmwood Cemetery

Last week Memphis Mayor A. C. Wharton called for the remains of Nathan Bedford Forrest, his wife, and the monument that stands above them, to be returned to the city’s Elmwood Cemetery. This move is not unexpected, as monument and the park surrounding it — renamed Health Sciences Park in 2013 — have been contentious in the city of Memphis for a long time now.

Last week Memphis Mayor A. C. Wharton called for the remains of Nathan Bedford Forrest, his wife, and the monument that stands above them, to be returned to the city’s Elmwood Cemetery. This move is not unexpected, as monument and the park surrounding it — renamed Health Sciences Park in 2013 — have been contentious in the city of Memphis for a long time now.

This call for Forrest’s return to Elmwood comes, of course, in the wake of several states taking action to remove or end official display of Confederate iconography, from flags to specialty license plates to statues. While I think we, as southerners, need to catch our breath and think a little more deliberately when it comes to monuments of long-standing, there is actually a strong and affirmative case — a pro-Forrest case, if you will — when it comes to the site in Memphis. I’ve communicated with several people who have been interested in Forrest for a long time, and know his story well. They point out that he and his wife, Mary Ann Montgomery Forrest, were originally interred at Elmwood, and it was not until the early 20th century, three decades after the general’s death, that their remains were moved to a central park downtown. It’s a case, in many respects, like that of Robert E. Lee at Washington College, now Washington and Lee University, where a later generation decided they knew better than the general himself what he wanted.

At Elmwood, he and Mary Ann would lie again among twelve hundred other Confederate soldiers. (Perhaps it’s not mere coincidence that the statue’s bronze gaze has been fixed on Elmwood all these years.) Besides which, a transfer of Forrest’s remains and re-interment a mile away at Elmwood would give the heritage folks the opportunity for a procession and pageantry the likes of which haven’t been seen since the burial of the H. L. Hunley crew at Charleston in 2004. Lord knows, to so many of Forrest’s fans practicing history consists mainly of dressing up and solemnly parading with Confederate flags. It’s a win for all concerned — for the Forrests, who apparently preferred being at Elmwood; for the city of Memphis that, rightly or wrongly, wants to be done with what used to be known as Forrest Park; and for the heritage crowd that, with a little nudging, can undoubtedly be convinced that a move is actually the right and proper thing to do. A recent Tennessee law would seem to prohibit moving Forrest and the monument, but with everyone on board with it, I’m sure enabling legislation in Nashville is a forgone conclusion.

Confederate graves at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis. Forrest should be here, too.

Confederate graves at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis. Forrest should be here, too.  The specific circumstances of the Forrest case make that call easy; the case for moving, or removing, other Confederate monuments is more difficult, and requires more deliberation. Speaking for myself, I’m ambivalent about it. While I adamantly support the authority of local governments to make these decisions, I’m not sure that a reflexive decision to remove them is always the best way of addressing the problems we all face together. Monuments are not “history,” as some folks seem to believe, but they are are historic artifacts in their own right, and like a regimental flag or a dress or a letter, they can tell us a great deal about the people who created them, and the efforts they went to to craft and tell a particular story. In 2015 it would be hard to find someone who would unequivocally embrace the message of the “faithful slaves” monument in South Carolina, but it can’t be beat as documentation of the way some white South Carolinians saw the conflict thirty years after its end, and wanted others to, as well. (Maybe York County could put a sign next to it with an arrow saying, “no, they really believed this sh1t!”)

The specific circumstances of the Forrest case make that call easy; the case for moving, or removing, other Confederate monuments is more difficult, and requires more deliberation. Speaking for myself, I’m ambivalent about it. While I adamantly support the authority of local governments to make these decisions, I’m not sure that a reflexive decision to remove them is always the best way of addressing the problems we all face together. Monuments are not “history,” as some folks seem to believe, but they are are historic artifacts in their own right, and like a regimental flag or a dress or a letter, they can tell us a great deal about the people who created them, and the efforts they went to to craft and tell a particular story. In 2015 it would be hard to find someone who would unequivocally embrace the message of the “faithful slaves” monument in South Carolina, but it can’t be beat as documentation of the way some white South Carolinians saw the conflict thirty years after its end, and wanted others to, as well. (Maybe York County could put a sign next to it with an arrow saying, “no, they really believed this sh1t!”)

I’ve written before about the Dick Dowling monument in Houston (right). It honors Dowling for his command of Confederate artillerymen at the Battle of Sabine Pass in 1863, but from its dedication in 1905, it was a rallying point for Houston’s Irish community, many of whom came after the war. (It was sponsored, in large part, by the Ancient Order of Hibernians.) Certainly today, as I learned firsthand, the emphasis at the annual ceremony there is much more Irish in character than Confederate. It means a great deal to those folks, many of whose Irish ancestors’ arrival in this country postdates the Civil War by decades. They have no personal connection to the war or to the Confederacy, yet the Dowling monument nonetheless serves as a common bond among them irrespective of the uniform worn by the marble figure at the top. It really would be a shame to lose that.

I’ve written before about the Dick Dowling monument in Houston (right). It honors Dowling for his command of Confederate artillerymen at the Battle of Sabine Pass in 1863, but from its dedication in 1905, it was a rallying point for Houston’s Irish community, many of whom came after the war. (It was sponsored, in large part, by the Ancient Order of Hibernians.) Certainly today, as I learned firsthand, the emphasis at the annual ceremony there is much more Irish in character than Confederate. It means a great deal to those folks, many of whose Irish ancestors’ arrival in this country postdates the Civil War by decades. They have no personal connection to the war or to the Confederacy, yet the Dowling monument nonetheless serves as a common bond among them irrespective of the uniform worn by the marble figure at the top. It really would be a shame to lose that.

I think we need to be done, done, with governmental sanction of the Confederacy, and particularly public-property displays that look suspiciously like pronouncements of Confederate sovereignty. The time for that ended approximately 150 years ago. But wholesale scrubbing of the landscape doesn’t really help, either, if the goal is to have a more honest discussion about race and the history of this country. I’m all for having that discussion, but experience tells me that it probably won’t happen. It’s much easier to score points by railing against easy and inanimate targets.

_________

Forrest monument image via PorterBriggs.com. Elmwood Cemetery image via ElmwoodCemetery.org.

Confederate Veterans on Forrest: “Unworthy of a Southern gentleman”

I was looking around recently for some background to the famous Pole-Bearers address given by Nathan Bedford Forrest in July 1875 at Memphis. In his speech to the Freedmen’s group, Forrest emphasized the importance of African Americans building their community, participating in elections, and both races moving forward in peace. Just prior to making his remarks, Forrest was presented a bouquet of flowers by an African American girl, and responded by giving the girl a kiss on the cheek. This single event is sometimes cited as proof that the former slave dealer and Klan leader “wasn’t a racist” or some similar nonsense, as if that modern term had much import in mid-19th century America.

I was looking around recently for some background to the famous Pole-Bearers address given by Nathan Bedford Forrest in July 1875 at Memphis. In his speech to the Freedmen’s group, Forrest emphasized the importance of African Americans building their community, participating in elections, and both races moving forward in peace. Just prior to making his remarks, Forrest was presented a bouquet of flowers by an African American girl, and responded by giving the girl a kiss on the cheek. This single event is sometimes cited as proof that the former slave dealer and Klan leader “wasn’t a racist” or some similar nonsense, as if that modern term had much import in mid-19th century America.

I’ll have more to say about the Pole Bearers speech another time, but if you ever wondered how Forrest’s actions that day were perceived by at least some of his former comrades in gray, now we know. They weren’t happy about it, and went to considerable efforts to say so – publicly. From the Augusta, Georgia Chronicle, July 31, 1875, p. 4:

![]()

Geez. Sounds like they were mad, huh?

________

Nathan Bedford Forrest Joins the Klan

Nathan Bedford Forrest is always a popular subject in Confederate heritage, but that’s never been more true than it is today. He’s frequently featured in the secular trinity of Confederate heroes, alongside Lee and Jackson. And like those two – and only those two – Forrest has achieved the modern apotheosis of Confederate fame, having his own page of t-shirts at Dixie Outfitters.

Nathan Bedford Forrest is always a popular subject in Confederate heritage, but that’s never been more true than it is today. He’s frequently featured in the secular trinity of Confederate heroes, alongside Lee and Jackson. And like those two – and only those two – Forrest has achieved the modern apotheosis of Confederate fame, having his own page of t-shirts at Dixie Outfitters.

But Forrest’s defenders often hold the line at one claim, that he was a prominent figure in the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan. Even as they struggle to rationalize the Klan of that period as a necessary counter against the supposed excesses of the Union League and other northern influences, they usually deny any involvement of Forrest in the Klan’s organizing or activities, except for the odd claim that Forrest, despite having no authority or connection to the group, successfully ordered them to stand down in 1869.

So did Forrest really join the Ku Klux Klan? Yes, he did. Was he really Grand Wizard of the group? Yes, he was. How do we know this? Because the old klansmen who were there tell us so.

Hey, Mississippi SCV: This is How It’s Done

There didn’t seem to be much else to be said about the Mississippi SCV’s Nathan Bedford Forrest commemorative license plate proposal, but Robert Moore suggested Wednesday that a better choice would be to put a generic Confederate soldier on it. This seems appropriate for several reasons, among others that there are a helluva lot more SCV members (and well as Mississippians generally) related to rank-and-file soldiers than there are descendants of cavalry generals. Such a plate might also serve as a point to generate constructive conversations with the public, including:

“Who was that man in the uniform?”

“What made-up the Confederate soldier, who, in turn, became the Confederate veteran?”

“How was the individual man part of the Confederate story?”

“Was he willing, unwilling?”

“Was he enthusiastic for ‘the cause’… for ‘a cause’?”

And so on. One of Robert’s commenters suggested the plates feature some of Don Troiani’s uniform studies. It’s a capital idea.

The SCV could issue five plates, one for each year of the war, each celebrating a “common man” (or woman) from the conflict. An early-war infantryman for 2011 (below). A civilian woman from Vicksburg in 2013. A former slave in the USCT for 2015. (Well, maybe that last one wouldn’t go over so well with the SCV. But it would sure work for a state-sponsored plate.) There are lots of other possibilities.

It’s colorful, it carries a bit of history, and it certainly comes closer to reflecting the Civil War experience of typical Mississippians better than one bearing the picture of a millionaire slave trader from Memphis. Granted, it doesn’t have quite the in-your-face impact of a big-ass flag out on the interstate, but sometimes less is more, ya know?

_________________________

Image: Soldier of the 17th Mississippi Infantry, Company I, Pettus Rifles by Don Troiani.

12 comments