Pension Records for Louis Napoleon Nelson

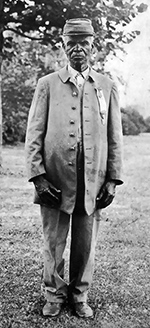

One of the best-known “black Confederate soldiers” is Louis Napoleon Nelson (right, c. 1846 – 1934), due in large part to the advocacy of his grandson, Nelson Winbush. There are any number of claims made for the nature of Nelson’s service, such as these:

One of the best-known “black Confederate soldiers” is Louis Napoleon Nelson (right, c. 1846 – 1934), due in large part to the advocacy of his grandson, Nelson Winbush. There are any number of claims made for the nature of Nelson’s service, such as these:

[Winbush’s] grandfather, Louis Napolean Nelson, was a private in Co. M, 7th Tennessee Cavalry of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. Private Nelson was a slave at the start of the war. He began his military service as a cook, then a rifleman, and finally a chaplain.

Virtually nothing, however, has been offered in the way of documentation of such claims. So in the interest of injecting something tangible into future discussions of Nelson’s activities during the war, here is his 1921 Tennessee Confederate pension file (PDF).

___________

The application clearly states in several places that Nelson’s service was limited to being a “servant and cook.” The fact that this is identified as a “colored man’s pension application” for an “ex=servant” is also relevant, or it would be if proponents of the black Confederate myth were interested in real evidence.

I’ve handled hundreds of the originals,they were encouraged to erase or mark out anything but cook,servant some obliged and went along some didn’t,to say these men were a myth is an insult to all of my veteran brothers,there’s many who did not go along with using these two categories….who do you think was giving out pensions? It’s not hard to figure out why this was

Unfortunately, Nelson’s pension application — a sworn and witnessed legal declaration, I should point out — is the only thing we have that approximates a primary source for his service during the war. The fact that eleventy-four thousand websites talk about Nelson’s service as a soldier, and virtually none of them mention or reproduce this application, simply underscores how far some people are willing to go in ignoring the historical record when it conflicts with their preferred narrative.

Yes, it’s hard to see how someone could accurately draw the conclusion that Nelson was either a “rifleman” or a chaplain from the pension records provided here. And, in truth, why would one have expected him to have served as anything but a cook, given the prevailing racial attitudes, particularly in the Southern army?

I like the line on the second image: “Give the names of the regimental and company officers under whom your *master* [my emphasis] served. Hmm. I wonder if *all* members of the SCV and UDC could name *their* ancestors’ “masters.”?

Take care,

Bob

Judy and Bob Huddleston 10643 Sperry Street Northglenn, CO 80234-3612 Huddleston.r@comcast.net

“The rule is perfect: in all matters of opinion our adversaries are insane.” —Mark Twain

Great work Andy.

An excellent example of actual research. The document speaks volumes.

That pretty much sums it up doesn’t it? How do they get rifleman and chaplain out of that? Not to mention the fact that the application form itself is an extremely strong indicator of what the slaves did during the war with the wording in the form itself.

As far as I know, all the rest is based on Nelson Winbush’s recollections of his grandfather, who died in 1934, when Nelson was about 5 years old. So it’s an account related by a very old man, to a very young child, as that child now recollects it almost 80 years later. There’s lots of room for vagueness and inaccuracy there, and none of it (AFAIK) can be independently documented.

That’s why I posted the pension record. Much of what is claimed about individual “black Confederates” is lore or oral tradition that is either unsupported, or directly contradicted, by the contemporary historical record. Given the celebrity of Louis Napoleon Nelson as a “black Confederate,” that actual historical documentation, endorsed by Nelson himself, must also be part of the historical discussion.

“As far as I know, all the rest is based on Nelson Winbush’s recollections of his grandfather, who died in 1934, when Nelson was about 5 years old. So it’s an account related by a very old man, to a very young child…”

If the account is true he would have told others beside a 5 year old.

Mr. Winbush lives in Kissimmee, Fl. His phone number is available on the net (whitepages.com). Why don’t you call and ask him about the story and its origins?

Of course you would find it objectionable that I’ve posted, complete and unedited, a sworn legal document attesting to Louis Napoleon Nelson’s wartime activities, signed by Nelson (who made his mark), and attested by sworn statements from two men who were with him at the time, his former master, Private E. R. Oldham, and First Sergeant T. A. Walker of the same company.

As for calling Mr. Winbush, I’m not interested in cold-calling anyone. (I tried that once with Brag Bowling, and he never called me back as he’d promised.) I don’t doubt Mr. Winbush’s sincerity at all, but at the end of the day it’s up to him to make his own case for the claims he makes, just as it is for all the rest of us.

Object? Not at all.

For 90% of these cases the only paper trail is an article in a newspaper (late 1800s/early 1900s) or a pension application from the 1920s/30s.

It’s the other 10% you don’t want to talk about.

Bummer has a hard time believing that Forrest would have any ex-slave riding with his men. This “old guy” doesn’t know a lot, but understands the “Grand Wizard” implicitly. No way, no how, not ever! Body servant, cook, driver, but never armed and on the line with his southern brethren.

Bummer

Maybe he lead church services among the other cooks and black laborers. That would not be outside the accepted roles for a black male in the CSA military. Over time that gets re-interpreted as “chaplain.”

FWIW, one of my ancestors was a Confederate chaplain. He held the rank of Captain which was a courtesy rank. Anyone want to claim that Mr. Nelson was made a Captain in the Confederate Army?

“Maybe he lead church services among the other cooks and black laborers.”

That’s entirely plausible. Perhaps even attended by white soldiers occasionally. Most accounts say he was an “unofficial” chaplain, which could mean almost literally anything.

One can argue the matter of combat service round or flat, but I believe it is important to note the criteria applied to Black Confederates by the Union Army. To wit: “In the fullest sense, any man in the military service who receives pay, whether sworn in or not, is a soldier because he is subject to military law. Under this general head, laborers, teamsters, sutlers and chaplains, are soldiers.”

August Kautz,

General, USA

CUSTOMS OF SERVICE FOR NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICERS AND SOLDIERS, 1864

Thanks for commenting. I’m familiar with the Kautz passage, although he was (obviously) not referring to the legal status of enslaved persons connected to the Confederate Army — or to the Confederate Army at all, for that matter. The line you quote is often cited in making the argument for men like Nelson to be formally considered as soldiers, but what’s never quoted with it is Kautz’ very next sentence:

Kautz then immediately cites long-standing U.S. Army regulations restricting enlistment to “free white male” persons, with a footnote that special provision had been made for the enlistment of African Americans during the present conflict, but “not for the regular service.” This “free white male” language is repeated verbatim in official C.S. Army regulations through the 1864 editions.

Nelson’s own signed, sworn statement identifies him as having worked in none of Kautz’ categories, nor is there evidence that he was paid (as Kautz requires) by the government, nor had any recognized status, either enlisted or as a civilian employee. Nelson’s own sworn statement identifies him as a personal servant and cook to an individual soldier enlisted in the 7th Tenessee Cavalry. Period, full stop. Everything else is oral tradition.

I think we should trust Louis Nelson and the men who were there with him at the time on this.

Andy, can you please elaborate on the “free white male” language in the CSA Army regulations. That would make an interesting post!

Sure. The language appears — unchanged as far as I see — in CS Army regulations from 1861 though 1864. (I haven’t found an 1865 issue of the regulations, but my guess is that a formal re-issue didn’t happen then; the CS War Department had other things going on right then.) Numerous copies of these can be found at OpenLibrary.org. This is from the 1862 edition:

It goes on from there to describe the procedures for ascertaining parental consent for minors, the oath of enlistment, and so on. The reference to “master” in No. 1400 is to cover prospective recruits who are legally apprenticed. Most of this is taken verbatim from contemporary U.S. Army regulations — see this 1861 example for comparison.

Also relevant to the discussion of “black Confederates” is this line from No. 1008, “no enlisted man in the service of the Confederate States shall be employed as a servant by any officer of the army.” That’s relevant because almost all the men now claimed as “black Confederates” are identified in contemporary records explicitly as personal servants.

So the regulations are quite clear — African Americans (up to March 1865) could not be formally enlisted into the Confederate army, and no man who was formally enlisted could be used as a personal servant. These regulations draw a bright, shining line between those who were considered enlisted soldiers and those who were not.

Advocates for the “black Confederate” meme often dismiss these foundational documents, pointing out that there are always exceptions, that the men in question were “unofficial” soldiers, and so on. I get that; I’ve been in and around large organizations enough to know that all sorts of things are done in practice that go against this or that regulation or rule. But saying someone was an “unofficial” whatever can mean almost literally anything, and acknowledging that exceptions to the regulations undoubtedly happened is not actually evidence that they did in any specific case. Usually what we’re left with, as in Louis Nelson’s case, a handful of historical documents (signed by Nelson himself) that tell one story, and oral tradition (usually passed through multiple generations) that tells a different, more extravagant one. The point is not to say that the latter is necessarily false, but rather to point out that there is no independent corroboration to support it, and it should be understood for what it is.

AH-

“Nelson’s own sworn statement identifies him as a personal servant and cook to an individual soldier enlisted in the 7th Tenessee Cavalry. Period, full stop.”

A private maintained his own personal servant and cook for the entirety of the war? Noooo…..

Sounds like he cooked for the company too-

“…E R Oldham further made oath to the following facts touching the applicant’s service in the Confederate Army:

The applicant Louis Nelson was a cook for E R Oldham in Co. M, 7th Tennessee Cavary & was with said company as a servant & cook at the close of the war.”

Aha, now, this I can address. Go look at the 1860 census for district 1, Lauderdale county, TN. The Oldhams were one of the wealthiest slave-owning families in their neighborhood. Their sons may have been privates, but they weren’t privates in anything resembling a modern army; they were volunteers, part of a group of close neighbors, all wealthy landowners’ sons, who got up their own company and chose their own officers. The memoir of CSO Rice, 2nd lieutenant of co. M, (and incidentally next-door neighbor of the Oldhams) says most of them brought servants.

If you love the South, shouldn’t you be interested in its real history?

clearly you skipped section 1399B that allowed persons of color to join, especially black male slaves who wished to defend states rights!!!

seriously, thanks. very interesting…

Interesting. My relative, CSO Rice, was in company M of the 7th Tenn Cav and wrote extensively about it for the Brownsville papers. He mentions two other men’s black servants by name, George, who was killed while riding alongside the men and laughing at the gunfire (the point of the anecdote seems to have been how brave George was) and Auterick, who ran away after a beating and revealed the campsite to the Union soldiers, resulting in an unexpected midnight awakening by a hail of fire. No one was hurt and Auterick returned to his previous service, although he was teased about revealing the campsite. Crazy. The white men seem to have felt it was only fair for him to try to get them killed, no hard feelings.

CSO Rice gives a list of the men who were “in at the end” at Gainsville. E.R. and Sidney Oldham are on it. Nelson is not.

The fact that the pension records state explicitly that Nelson’s wife cannot receive a pension because Nelson was a servant, not a soldier, would seem to put an end to the discussion. I also love the part where ER Oldham writes asking them to please consider his servant’s pension because his conduct is so nice. Real affectionate, that is, when he was wealthy and these pensions were only offered to those in penury. You would think if Oldham were really grateful for his service, he wouldn’t make him go on the dole.

It’s interesting that you can see in the pension records exactly the moment at which the truth was swapped for the myth. It’s that dear old Southern lady, ER Oldham’s wife. The moment her husband is dead and can’t argue, she writes to Washington claiming Nelson was a brave soldier. And using his made-up title “General” socially, as if he were a real general in the real Confederate army, when in actuality he was only a private. That sort of stolen valor would get you arrested today, but it was par for the course for these ex-Confederates.