Old Pete, “Slave Raids” and the Gettysburg Campaign

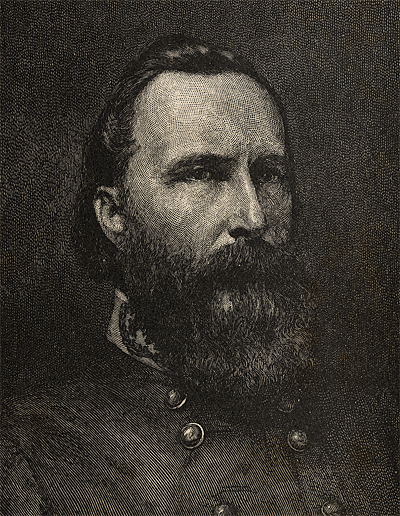

One hundred forty-seven years ago today, Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet, writing through his adjutant, ordered General George Pickett to bring up his corps from the rear to reinforce the main body of the Army of Northern Virginia. The lead elements of the armies of Robert E. Lee and George Meade had come together outside a small Pennsylvania market town called Gettysburg. The clash there would become the most famous battle of the American Civil War, and would be popularly regarded as a critical turning point not just of that conflict, but in American history. More about Longstreet’s order shortly.

I was thinking about that when I recently read an essay by David G. Smith, “Race and Retaliation: The Capture of African Americans During the Gettysburg Campaign,” part of Virginia’s Civil War, edited by Peter Wallenstein and Bertram Wyatt-Brown. All but the last page and a few citations is available online through Google Books. It’s not a pleasant read.

During the Gettysburg Campaign, soldiers in the the Army of Northern Virginia systematically rounded up free Blacks and escaped slaves as they marched north into Maryland and Pennsylvania. Men, women and children were all swept up and brought along with the army as it moved north, and carried back into Virginia during the army’s retreat after the battle. While specific numbers cannot be known, Smith argues that the total may have been over a thousand African Americans. Once back in Confederate-held territory, they were returned to their former owners, sold at auction or imprisoned.

That part of the story is well-known. What makes Smith’s essay important is the way he provides additional, critical background to this horrible event, and reveals both its extent across the corps and divisions of Lee’s army, as well as the acquiescence to it, up and down the chain of command. The seizures were not, as is sometimes suggested, the result of individual soldiers or rouge troops acting on their own initiative, in defiance of their orders. The perpetrators were not, to use a more recent cliché, “a few bad apples.” The seizure of free Blacks and escaped slaves by the Army of Northern Virginia was widespread, systematic, and countenanced by officers up to the highest levels of command. This event, and others on a much smaller scale, were so much part of the army’s operation that Smith argues they can legitimately be considered a part of the army’s operational objective. Smith is blunt in his terminology for these activities; he calls them “slave raids.”

These ugly episodes did not spring up spontaneously; it was a violent and entirely predictable result of multiple factors that had been building for months or years. For a long time, there was growing resentment in Virginia over escaped slaves seeking refuge in Pennsylvania, where there was considerable sympathy for the abolitionist cause, and stops on the Underground Railroad. These tensions increased substantially after the outbreak of the war, as Virginia slaves learned that they could expect to be safe as soon as they reached Union territory, where they would be considered contraband. White Southerners’ resentment of this situation redoubled again in the fall of 1862, with the news that the Lincoln administration would issue the Emancipation Proclamation. This further encouraged slaves to flee to the North, and made it clear to slaveholders — had it not been clear before — that defeat would put an end to the “peculiar institution,” and upend the economy and culture that went with it.

A November 1862 Harper’s Weekly (New York) illustration showing Confederate officers driving slaves further south, to put them out of reach of the Federal armies in advance of the Emancipation Proclamation. The accompanying article told of two white men who escaped to Union lines and

upon being questioned closely, they admitted that they had just come from the James River; and finally owned up that they had been running off “niggers” having just taken a large gang, belonging to themselves and neighbors, southward in chains, to avoid losing them under the emancipation proclamation. I understand, from various sources, that the owners of this species of property, throughout this section of the State, are moving it off toward Richmond as fast as it can be spared from the plantation; and the slaveholders boast that there will not be a negro left in all this part of the State by the 1st of January next.

Against this backdrop, the organization of Federal units of Black soldiers, comprised of both escaped slaves and free men, was taken as an outrage. It struck a raw nerve, never far off in the Southern psyche: fear of a slave insurrection. The prospect of African American men in blue uniforms was taken as an extreme provocation, so much so that it was proposed in the Confederate congress — and endorsed by General Beauregard, the hero of Fort Sumter — that all Federals captured, black or white, should be summarily executed. This proposal was never adopted, but the Confederate congress did eventually pass, in May 1863, a proclamation instructing President Jefferson Davis to exercise “full and ample retaliation” against the North for arming black soldiers.

Finally, there was simple revenge. The Union army’s shelling of Fredericksburg several months before had been a particular sore point, that festered for months as the Confederate army went into winter quarters nearby. One officer, determined to fix the destruction there in his mind’s eye, made a special visit to that town one last time before setting out on the road north into Maryland and Pennsylvania.

So when Lee’s army finally marched north in June 1863, it was fully infused with the intent to exact “full and ample retaliation” on Union territory as it passed. Lee issued orders against the indiscriminate destruction of civilian property, but made no mention of seizing African Americans, whether free or former slaves. In his essay, Smith points out that diaries, letters and even official reports from every division in Lee’s army mention Confederates rounding up African Americans and holding them with the army. The practice was tolerated — if not actively encouraged — by officers at all levels of the army. Even Lieutenant General Longstreet, the most senior of Lee’s corps commanders and effectively the second-in-command of the Army of Northern Virginia, acknowledged the practice and accommodated it. In sending orders to General Pickett, whose corps was bringing up the rear of the army, Longstreet, writing through his adjutant, G. M. Sorrel, sent word on July 1 — the day the two armies first engaged each other — to move his troops toward Gettysburg. In closing he added, “the captured contrabands had better be brought along with you for further disposition.”

“Further disposition” here refers to imprisonment, auction, enslavement, and (often) severe punishment at the hands of a former-and-once-again master.

Those thirteen words closing words of Longstreet’s order are damning, in that they show full well that the seizure and abduction of African Americans was, if not official policy, widely tolerated and made allowance for, even at the highest levels of the Confederate command structure. Longstreet was second-in-command; while his order does not prove Lee knew and approved of this practice, it’s hard to imagine he was unaware of it, and there’s no evidence that he publicly objected to it, or made any effort to curtail it. My intent here is not to condemn Longstreet specifically — the de facto policy neither originated nor was actively encouraged by him — but to demonstrate that the forcible abduction of free African Americans and escaped slaves was known and tolerated, from the lowest private to the most senior generals.

There are many questions, many aspects, of the Civil War that are legitimate sources of controversy and dispute. There are questions that serious historians will argue about as long as anyone remembers this conflict, saying that this politician’s actions were justified by that event, or that general made the right decision because he didn’t know those troops were on the other side of the river. The abduction of free Blacks and escaped slaves from Maryland and Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg campaign is not one of those events. It cannot be justified, or rationalized, or denied. It can only be ignored.

But it shouldn’t be.

Andy,

Ted Alexander wrote an excellent essay on this subject in North and South magazine some years ago.

Thanks, I’ll look for that.

Somebody with the same initials as me wrote a fine piece on this for CWTI back in 2001 😉 It’s in the issue that has George Meade on the cover.

As to the Longstreet quote, via Sorrell, is there any other documentation that supports the idea he was referring to “contrabands” in the same context as the Federal Army did regarding escaped slaves? Contraband could also be taken to mean anything they had taken from within the Northern states which they felt would deprive their “enemy” of material with which to wage war or support the war effort, especially livestock to feed the army. It seems odd to me that the southerners would use the same word as opposed to saying “negroes” perhaps. The newer application (at that time) of the word “contrabands” might not fit here as easily as assumed. I understand the impulse to think of it in the same context, but it could be a leap of faith.

John, that’s a great question, one I’ll try and look into. The Longstreet/Sorrell quote appears in this context in a number of highly-regarded secondary works, but it’s always useful to look back and re-affirm conventional understandings.

The fact that he said “contrabands” instead of “contraband” suggests he was talking about a group of people, i.e., blacks, IMO. It could simply be a typo, but there is too much evidence of what was going on for this to absolve the entire army.

[…] Have Received Provocation Enough’ — an expansion of my earlier piece on the seizure of slaves during the Gettysburg […]

[…] ELSEWHERE: “The seizure of free Blacks and escaped slaves by the Army of Northern Virginia was widespread… […]

Mr. Hall…..can we expect a blog posting tomorrow or the next day on the forced enlistment of servants into the USCT in the Dept. of the South? Please try and feign the same outrage in this post please and perhaps utilize “Glen Beck’s Chalkboard” to explain the difference. BTW bad old South Carolina is doing this on Folly Beach this Friday evening at 1800hrs.

http://follycurrent.com/2011/07/11/the-fallen-nineteen-of-folly-beach-civil-war-historical-marker-unveiled/

Thanks for commenting, K.P. I don’t have anything currently in the pipeline on the forced enlistment of USCTs, but who knows? I do think that story is somewhat better known than the seizure of African Americans (both runaway slaves and those born free) during the Gettysburg Campaign, and objectively less odious. A forcibly conscripted soldier is still not a slave.

If you’re looking for equivalency with the forced conscription of contrabands in the USCT, I’d argue that a better analogy is the conscription of both slaves and free African Americans into non-combatant roles supporting Confederate armies in the field. The CS was not remotely shy about doing that, and there were actually calls for free blacks to be rounded up for service first, so as to minimize the pushback from slaveholders who objected to the seizure of their labor force.

Thanks also for the link to the Folly Beach marker unveiling.

Someone could write a valuable book comparing and contrasting both of these operations if no one has already. Are you aware of such a work? I am looking forward to going over to Folly tomorrow.

I don’t know of a single work that contrasts those two things directly.

If you take pictures at Folly, maybe you can post them somehwere?

Lack of labor was a constant source of irritation and complaint in the Confederacy. Especially in coastal cities like my Charleston where lack of manpower was made up by extensive fortifications and heavy guns. Genl Beauregard had an ongoing feud with Gov. Bonham over lack of labor on fortifications and the official record is full of their letters back and forth. I can’t speak for you but I have read enough of your posts here and elsewhere to think that you recognize that whether you take a man and force him against his will to dig fortifications, harvest crops, or enlist in the army at the point of a bayonet that it means that man doesn’t own his labor or service and that he is a slave. Maybe you see it differently…….and if so that’s what blogs are for!

We will have to disagree on that. In the context of mid-19th century America, slavery was a specific thing, clearly defined by law and society — it’s not just about being forced to labor against one’s will. Conscripted soldiers, and even free African Americans conscripted into military labor, retained some most legal rights and a defined term of service that slaves simply did not have access to, ever. Slavery is a very specific thing, even when the living and working conditions of the slave are objectively better than those of free men and women.

It’s very common these days, especially in political rhetoric, to use slavery in the 1860s as an analogy to modern situations where people are compelled (directly or indirectly) to do things they don’t want to. That, to me, reflects a very, very poor understanding of the “peculiar institution” as it actually existed in the first half of the 19th century.

We don’t have to agree and I respect your opinion. I guess that I just see a difference between a man being conscripted into the army by law and expeditions into the interior to “round up” soldiers. I will be glad to forward you video and pictures from Folly Beach. You have my email so if you will send me a message containing yours I will send to you.

Thanks, I’d appreciate that.

The Confederate officers should have tried for treason and war crimes and hung after the war. Like Sherman said”They started it”

First the elected Confederate politicians. Then maybe the senior soldiers. I don’t think the average CSA second lieutenant necessarily needed to be hanged. The average Governor, General or senator did.

Two brief comments: 1) The North invaded the South. 2) As always, the victors write (rewrite) history.

Forget Ft. Sumter or are you just ignoring the facts completely?

I give him credit for being succinct.

… to clear up confusion on “contraband”, check the references in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Contraband_(American_Civil_War) , key quotation being “persons of color, commonly known as contrabands” in September 1861