NatGeo’s Secret Weapon of the Confederacy

Update: I didn’t see the show myself, but I hear (from some highly-discerning folks) that it was pretty good.Anybody here catch it? Let me know in the comments.

_____________________________

On Thursday evening the National Geographic Channel will air “Secret Weapon of the Confederacy,” exploring the short, eventful life of the submersible H. L. Hunley. From the website:

It was the first submarine ever to sink an enemy ship, but after only one successful mission the H.L. Hunley vanished with its crew and lay hidden for more than a century. The circumstances surrounding the disappearance of the Confederacy’s secret weapon have remained an enduring mystery since the Civil War era, but now NGC has uncovered what may have brought it down.

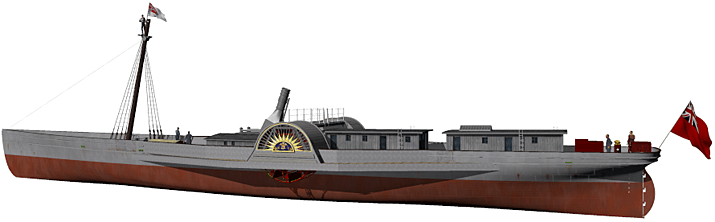

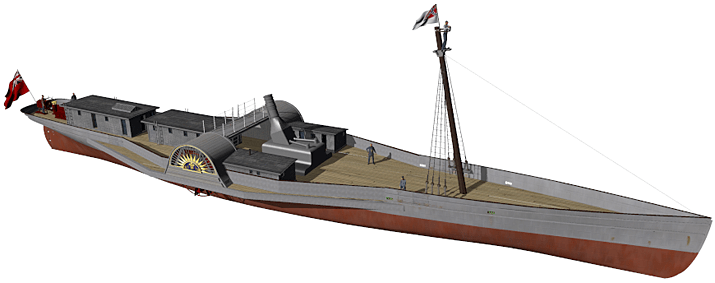

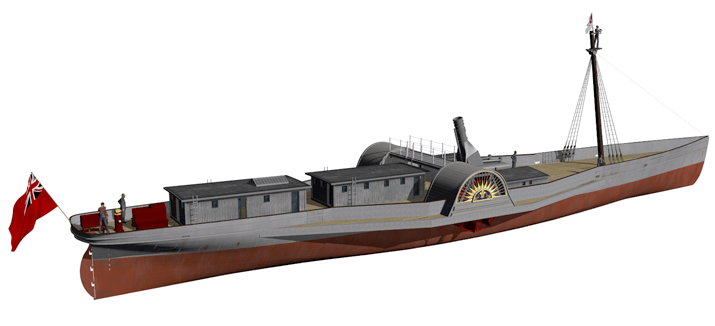

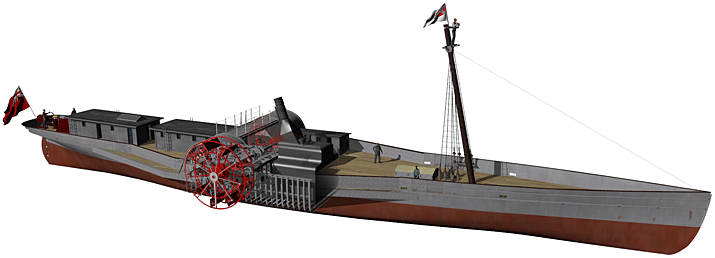

Hunley has always been a favorite of mine. Some old renderings of my model of the boat, based on plans by Michael Crisafulli, after the jump:

Blue and Grey, Red and Blue

So I’m reading this new (to me) blog, Lancaster at War, where Vince has taken a 19th century stereo pair and converted them into one image that can be viewed with those red/blue glasses you can get more-or-less anywhere. At his suggestion, I tried it out using these instructions and this Civil War stereoview. This is the result; it seems to work best if you lean back from the screen a bit.

Then there’s Captain Semmes of infamous Confederate raider Alabama. More background to this image here.

Only Cartophiles Need Apply

One of the traits often ascribed to Robert E. Lee was his uncanny ability to read terrain. He had, according to some, an almost preternatural ability to see on the other side of the hill, to know intuitively how best to position his forces for maximum effect on ground he’d never traversed before. His engineer’s eye for terrain didn’t always serve him well, but it did more reliably than most officers’.

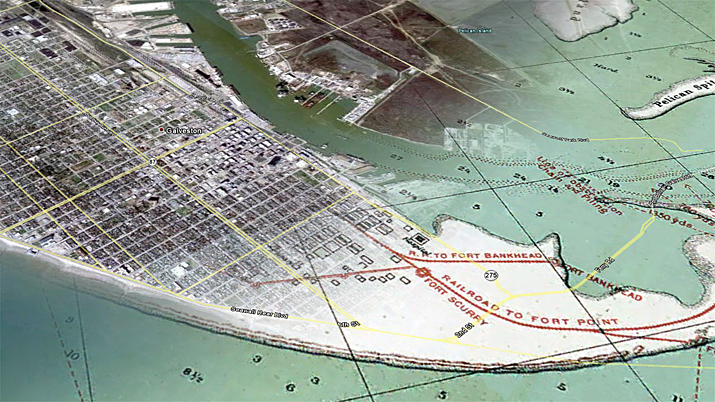

I thought about that when I discovered this index of (mostly) Civil War era maps from the U.S. War Department, Office of the Chief of Engineers records at the National Archives. It’s a very large collection, and most files can be either previewed in small scale (“access image”) size or downloaded, in TIFF format, at full resolution. To make use of the latter, you’ll need some good graphics software and a fast Internet connection; this chart, which seems to be the basis for the plan of Galveston in the OR Atlas, is a whopping 106MB at full resolution.

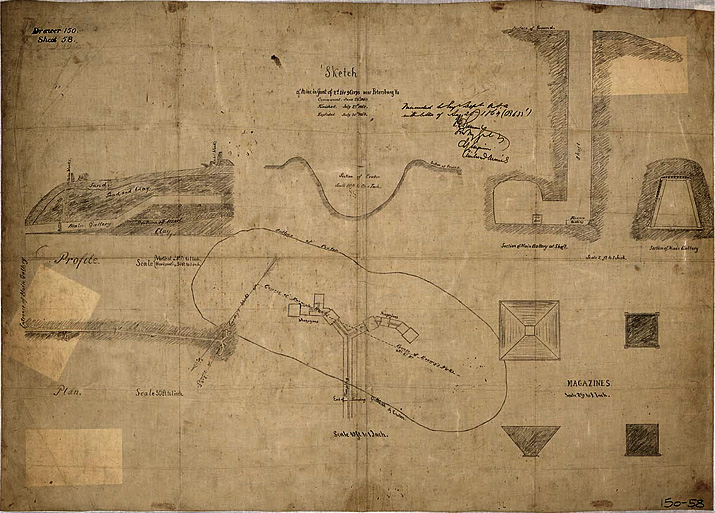

There’s also an index to plans of (mostly) Civil War era fortifications and military installations from the same records group. This set, interestingly, includes a detailed diagram of the tunneling done for the famous mine during the siege of Petersburg:

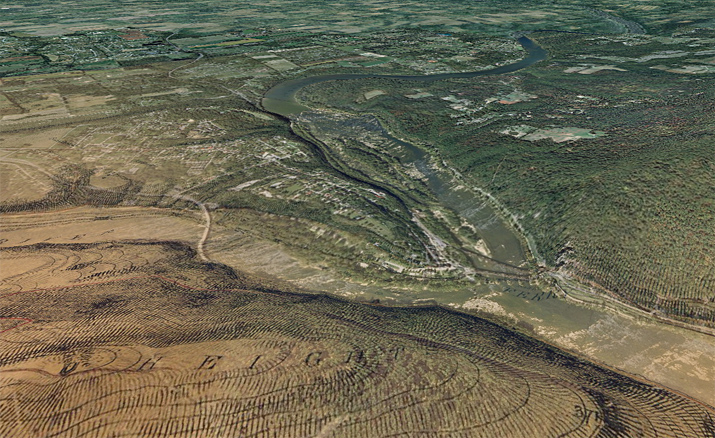

On a somewhat related note, I’ve begun working with ArcGIS Explorer, a freeware version of the professional ArcGIS mapping software. I never bothered much with ArcGIS because the desktop version simply wasn’t within my budget, but ArcGIS Explorer is free, with either online (Mac and PC) or desktop (PC only) versions. Furthermore, the full version, with all the bells and whistles, is now available for home use at an annual subscription rate of $100 per year, which puts it well within the range of all sorts of folks who had been priced out of the market before.

Folks who’ve followed this blog know how useful I’ve found Google Earth to be, particularly when it comes to overlaying historic maps and diagrams on their modern locations. It’s a bit of a headache to do, though, requiring lots of trial-and-error to scale, rotate and place the map overlay correctly. ArcGIS makes that process quite a bit simpler, provided you’re working with an historic map that shows precise points that can be identified on a modern map or aerial image. (It’s also essential that the historic map be an actual, surveyed map; there’s no point in trying to overlay a quick sketch map over a modern chart and expect things to line up.) ArcGIS Explorer allows only the minimum of three points to allign and scale an overlay, but (as I understand) the full version allows the user to plot additional reference points, which should make the alignment that much more precise.

But enough blathering on. If anyone out there knows of any ArcGIS tips or tricks, pass ’em along. In the meantime, here’s some cartographic eye candy, comparing an 1863 U.S. Coastal Survey chart of Charleston Harbor with modern, aerial images. First, Charleston itself:

“The work of soldiers amounts to very little.”

Just two days before Arthur Fremantle toured the batteries defending the eastern end of Galveston Island, the Confederate military engineer in charge of designing and building the defenses wrote out his report for the month of April 1863, outlining the work accomplished to date, and some of the challenges still to be overcome. Colonel Valery Sulakowski (1827-1873, right) was a Pole by birth, and a former officer in the Austrian army. After emigrating to the United States in the late 1840s, he worked as a civil engineer in New Orleans. He’d met General Magruder early in the war, in Virginia, and after the island was recaptured from Federal forces on New Years Day 1863, set about expanding the island’s defenses. Sulakowski had the reputation of a strict disciplinarian but, along with another immigrant engineering officer, Julius Kellersberger, is credited with quickly expanding the fortifications at Galveston and making the island a much more defensible post than it had been during the first eighteen months of the war.

Just two days before Arthur Fremantle toured the batteries defending the eastern end of Galveston Island, the Confederate military engineer in charge of designing and building the defenses wrote out his report for the month of April 1863, outlining the work accomplished to date, and some of the challenges still to be overcome. Colonel Valery Sulakowski (1827-1873, right) was a Pole by birth, and a former officer in the Austrian army. After emigrating to the United States in the late 1840s, he worked as a civil engineer in New Orleans. He’d met General Magruder early in the war, in Virginia, and after the island was recaptured from Federal forces on New Years Day 1863, set about expanding the island’s defenses. Sulakowski had the reputation of a strict disciplinarian but, along with another immigrant engineering officer, Julius Kellersberger, is credited with quickly expanding the fortifications at Galveston and making the island a much more defensible post than it had been during the first eighteen months of the war.

Sulakowski’s report, being essentially simultaneous with Fremantle’s observations, also give a better sense of what the British officer saw but declined to record in detail due to the sensitive military nature of the information. From the Official Records, 21:1063-64:

ENGINEER’S OFFICE, Galveston, April 30, 1863.

Capt. EDMUND P. TURNER,

Assistant Adjutant-General, BrownsvilleCAPTAIN:

I have the honor to make the following report for the month of April, 1863:

Fort Point–casemated battery.–The wood, iron, and earth work was completed during this month; five iron casemate carriages constructed; the guns mounted; cisterns placed, and hot-shot furnace constructed. It has to be sodded all over, the bank being high and composed of sand. Two 10-inch mortars will be placed on the top behind breastworks.

Fort Magruder–heavy open battery.–The front embankment, traverses, platforms, and magazines were completed during this month; two 10-inch columbiads mounted. The Harriet Lane guns are not mounted, for want of suitable carriages, which are under construction. Bomb-proofs and embankment in the rear commenced and the front embankment sodded inside, top and slope. With the present force it will require nearly the whole of this month to complete it.

Fort Bankhead.–Guns were mounted and the railroad constructed during this month.

South Battery.–For want of labor the reconstruction of this battery was commenced within the last few days of the month; also the construction of the railroad leading to it.

Intrenchment of the town is barely commenced, for want of labor.

Obstructions in the main channel.–Since the destruction of the rafts by storm, before they could be fastened to the abutments, this plan of obstruction had to be abandoned for the want of material to repair the damage done. The present system of obstructing consists of groups of piles braced and bolted and three cable chains fastened to them, the groups of piles in the deepest part of the channel to be anchored besides. This was the first plan of obstructing the channel on my arrival here; but being informed by old sailors and residents that piles could not be driven on account of the quicksand, and not having the necessary machinery then to examine the bottom, it was rejected. Having constructed a machine for this purpose, it is certain that piles can be driven and are actually already driven half across. This obstruction will be completed and the chains stretched from abutment to abutment by the 10th of May. Sketch, letter A, represents the work.

Obstructions at the head of Pelican Island.–Two-thirds done. It will require the whole of May to complete this obstruction and erect the casemated sunken battery of two guns, as proposed in my last report. These works are greatly retarded by the difficulty of procuring the material.

Pelican Spit ought to be fortified, as submitted in my last report, with a casemated work. For its defense two 32-pounders and one 24-pounder can be spared. This work is of great importance, but it had to be postponed until the intrenchments around the town shall be fairly advanced.

The force of negroes [sic.] on the island consists of 481 effective men. Of these 40 are at the saw-mills, 100 cutting and carrying sod (as all the works are of sand, consequently the sodding must be done all over the works), 40 carrying timber and iron, which leaves 301 on the works, including [harbor] obstructions. The whole force of negroes consists, as above, of 481 effective, 42 cooks, 78 sick; total, 601.

In order to complete the defenses of Galveston it will require the labor of 1,000 negroes during three weeks, or eight weeks with the present force. The work of soldiers amounts to very little, as the officers seem to have no control whatever over their men. The number of soldiers at work is about 100 men, whose work amount to 10 negroes’ work.

Brazos River.–After having examined the locality I have laid out the necessary works, and Lieutenant Cross, of the Engineers, is ordered to take charge of the construction. Inclosed letter B is a copy of instructions given to Lieutenant Cross. Sketch, letter C, shows the location of the proposed works at the mouth of Brazos River.

Western Sub-District.–Major Lea, in charge of the Western Sub-District, sent in his first communication, copy of which, marked D, is inclosed. I respectfully recommend Major Lea’s suggestions with regard to procuring labor to the attention of the major-general commanding. I have ordered a close examination of the wreck of the Westfield, which resulted in finding one 8-inch gun already, and I hope that more will be found. Cash account inclosed is marked letter E; liabilities incurred and not paid is marked letter F.(*)

I have the honor to remain, respectfully, your obedient servant,

V. SULAKOWSKI.

My emphasis. “Major Lea,” mentioned in the last paragraph, is Albert Miller Lea, a Confederate engineer and staff officer who, after the Battle of Galveston four months before, had famously found his son, a U.S. naval officer aboard the Harriet Lane, mortally wounded aboard that ship.

Sulakowski’s report also mentions the importance of sodding the built-up earthworks, as the sand of which they were constructed would otherwise blow down in drifts. That technique was also used in the fortifications around Charleston, as in this detail (above) of a painting of Fort Moultrie by Conrad Wise Chapman. At the center of the image, African American laborers gather sand to be used in repairing the fort.

_____________

Image: Detail of “Fort Moultrie” by Conrad Wise Chapman. Museum of the Confederacy.

U.S.S. Monitor Turret Revealed

Via Michael Lynch at Past in the Present, there are about three weeks left to see the 120-ton turret of the Union ironclad Monitor, currently undergoing restoration at the Mariner’s Museum in Newport News.The turret, recovered from the sea floor off Cape Hatteras in 2002, has been kept in a flooded tank of fresh water almost the entire time since then, allowing the salts that have penetrated the iron to gradually leach out. After a thorough cleaning, the turret will be flooded again, to to continue desalinization, a lengthy process that may take up to 15 more years. Even with the tank drained, it’s slow, painstaking work:

[Gary] Paden is an objects handler working in the USS Monitor Center at The Mariners’ Museum. He was gently nudging, hour after painstaking hour, a wrought-iron stanchion from the 9-foot-tall revolving gun turret that once sat atop the Civil War ironclad.

The stanchions rimmed the roof of the Monitor and held up a canvas awning to shelter the crew from the broiling sun. The stanchions needed to be removed so they could be separately treated for conservation.

Last week Paden strived to remove one of those stanchions from its bracket using a hydraulic jack. “I spent seven hours on it yesterday,” Paden said. “So far it’s been the most difficult one.”

Several other workers came in closer to watch, including Dave Krop, manager of the Monitor conservation project.

Paden said most of the tools used in restoring the various components of the Monitor brought up from the ocean’s floor were improvised. The hydraulic jack is an auto body tool used to fix dents.

He pressed the jack into the point where the stanchion met the bracket. A moment later, the stanchion fell from its 149-year-old position.

“Wow,” Krop said. “You got it off. Pretty awesome! That’s pretty awesome!”

Several handlers nearby paused from their snail’s-pace labors to savor the moment, beaming in Paden’s direction.

A few years ago I visited Mariners while doing research on another vessel and, after talking to one of the conservators there about my own project, was offered the chance to take a brief tour of the lab where they were working on Monitor artifacts. (That says less about me than it does about how much they wanted to show off the work they were doing there, and rightly so.) I wasn’t allowed to take pictures, but they showed me a first a life-sized color photograph of an encrusted dial from the engine room — a steam gauge, I think — and then, with a well-practiced flourish, pulled back a cloth covering the same artifact, now almost pristine, looking as new as the day the ship sailed over 140 years before. Folks like Gary Paden and Dave Krop don’t get a lot of attention, because their work is all behind-the-scenes, but it’s important to recognize what they do, that benefits every history buff and museum-goer.

Moment of nerd: the dents made to the exterior of Monitor‘s turret by the guns of C.S.S. Virginia are still visible, 149 years later, on the interior of the upside-down turret. Additional damage to the deck edge is visible at lower right.

More video via the New York Times here. The tank containing Monitor‘s turret will be drained during the week during the rest of August. I hope some of y’all can make the trip. I’m certain you won’t be disappointed. For the rest of us, there’s always the webcam.

Added: Three additional images showing the interior of the turret, all from Miller’s book (top to bottom): Contemporary illustration from Harper’s Weekly; original drawing from Ericsson’s plan; and a modern cutaway illustration by the great Alan B. Chesley.

_________

Top color photo: “Dave Krop, who manages the Monitor conservation project, works inside the inverted turret at the Mariner’s Museum. Visitors can watch the work from viewing platforms or online.” Credit: Steve Earley, the Virginian-Pilot. Archival photo: Library of Congress. Bottom photo: Diorama of interior of Monitor‘s turret in action by Sheperd Paine, from U.S.S. Monitor: The Ship that Launched a Modern Navy by Lt. Edward M. Miller, USN.

Aye Candy

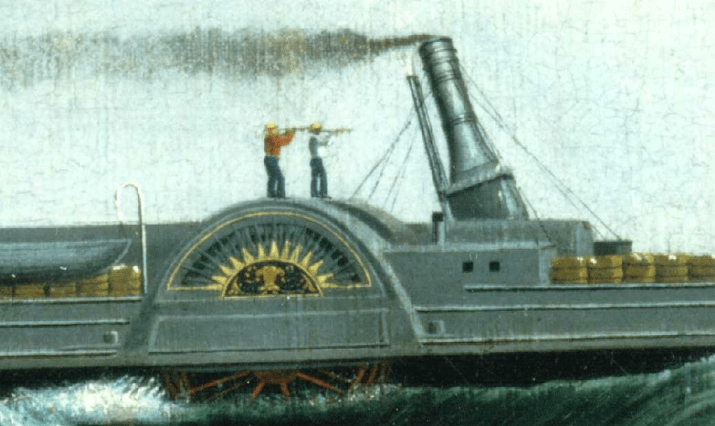

Got some additional work done this weekend on the Denbigh model, which continues to shape up nicely. This time I focused on the side houses, placed outboard on the sponsons, just ahead of the paddleboxes. Here are the sidehouses as shown in the 1864 painting of the ship:

If they’re depicted correctly in the painting — and there’s no way to know for sure, as all of that wooden structure burned when the ship was destroyed by a Federal boarding party in May 1865 — then these little cabins must have been tiny, cramped spaces. The artist, Thomas Cantwell Healy (1820 – 1899), appears to have depicted the human figures in the painting a bit too small compared to the overall scale of the steamer, and if they were the size depicted. No plans of Denbigh are known to exist, but plans of another paddle steamer, Will o’ the Wisp, show the small sidehouses to be used as a storeroom (starboard) and a lamp room (port), with a water closet on each side, immediately forward of the paddlewheel, where waste could be flushed directly into the sea below. On Will o’ the Wisp there was a small galley in one of the sidehouses abaft the wheel. Denibgh didn’t have that second set of sidehouses, but the stardboard-side house does appear to have a chimney, so perhaps that structure was fitted as the galley.

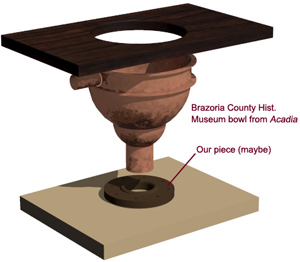

In 2002 we recovered, from the space outboard of the hull, just forward of the wheel, a heavy, iron ring or flange (right), that coincidentally (or maybe not) seems to be just about the correct size to match the outflow pipe from a copper toilet bowl recovered from the wreck of Acadia in the 1970s by an amateur salvor, Dr. Wendell Pierce, now part of the collection at the Brazoria County Historical Museum in Angleton, Texas. Kinda neat.

In 2002 we recovered, from the space outboard of the hull, just forward of the wheel, a heavy, iron ring or flange (right), that coincidentally (or maybe not) seems to be just about the correct size to match the outflow pipe from a copper toilet bowl recovered from the wreck of Acadia in the 1970s by an amateur salvor, Dr. Wendell Pierce, now part of the collection at the Brazoria County Historical Museum in Angleton, Texas. Kinda neat.

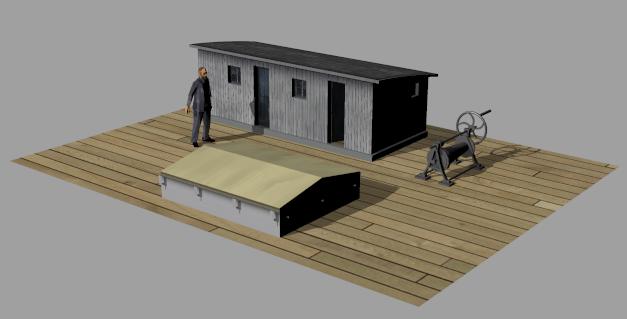

More images of the updated model:

One of the sidehouses, shown with a generic cargo hatch and windlass.

And finally, a test illustration showing the midships hull structure and machinery, superimposed on the new model. Full size image here.

___________

Image: Detail of 1864 painting of paddle steamer Denbigh by Thomas Cantwell Healy. Private collection.

1865 Galveston in Google Earth

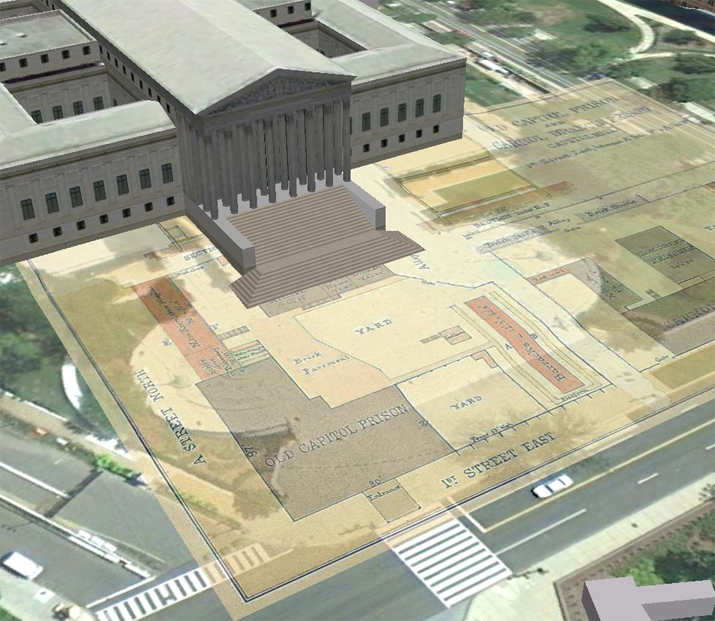

Google Earth is a pretty amazing tool, whose functionality is often limited only by the imagination of the user. One feature that I enjoy and use frequently, is to add an “image overlay,” which essentially allows the user to take maps and diagrams from other sources from other sources and lay them out on the modern, aerial views stored in Google. It takes practice, particularly in scaling the original image to match plot in Google Earth, but usually worth the effort. In doing the research on my post on the Henry Wirz execution photos, for example, I overlaid a diagram of the Old Capitol Prison to see how it fits on the site. While it’s usually state that the current Supreme Court building occupies that site, in fact most of the Old Capitol Prison stood in what is now the plaza in front of the Supreme Court, and the gallows were located about halfway between the front steps and of the present-day court and the curb:

Is this information useful to anyone? Probably not, unless you happen to be a history-cartography-techo-dweeb, in which case it’s priceless.

Anyway, for those interested, here are the Google Earth files for Galveston in 1865, from Plate XXXVIII of the Atlas for the Official Records (2MB), and for the Old Capitol Prison (215K). Google Earth is required.

Are there any other good Civil War-related Google Earth applications I should know about?

______________

Is a Wirz Execution Photo Misidentified?

Henry Wirz (1823-1865) remains one of the most controversial figures of the American Civil War. Reviled in the North for his role as commandant of the notorious Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, Georgia, Wirz was tried in the summer of 1865 in Washington, D.C. and condemned to death. He was hanged on November 10, 1865, on a scaffold set up in the courtyard of the Old Capitol Prison (below), on what is now the site of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Wirz continues to have many supporters, who argue that he did the best he could to care for the Federal soldiers imprisoned at Andersonville, with the very limited resources he had at his disposal. The Confederacy, they argue, had not sufficient means to care for its own population, much less enemy prisoners, and point to hard conditions in Northern prisons, where lack of resources was far less a problem, in response. They also point out that one of the key witnesses in the prosecution’s case against Wirz was apparently an imposter, who could not have witnessed the things he testified to under oath. Nearly a century and a half after his death, efforts are still being made to exonerate Wirz and restore his reputation.

This post isn’t about any of that.

Wirz’ execution was the subject of a famous sequence of four photographs, now part of the collection of the Library of Congress, taken by Alexander Gardner. The sequence of the photos, as indicated by both their captions and catalog numbers, is usually given as follows:

- Reading the death warrant to Wirz on the scaffold, LC-B817- 7752

- Adjusting the rope for the execution of Wirz, LC-B8171-7753

- Soldier springing the trap; men in trees and Capitol dome beyond, LC-B8171-7754

- Hooded body of Captain Wirz hanging from the scaffold, LC-B8171-7755

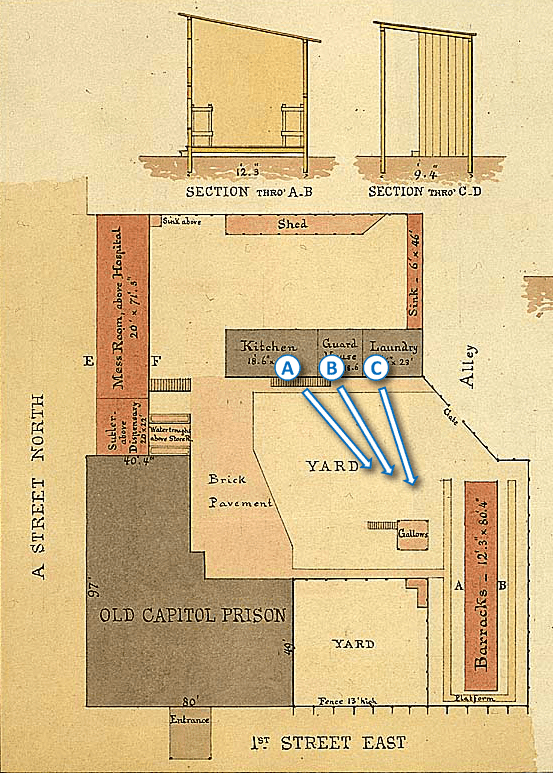

The four images were taken from three different locations (below). The first two appear to have been taken from the roof of the prison kitchen (Point A), looking diagonally across the yard where the scaffold is set up. For the image of Wirz’ body hanging from the beam, Gardner moved the camera to the left, and to a higher position to get a clearer view of the body in the trap (Point B). Gardner may have also wanted to frame his shot to capture the dome of the U.S. Capitol in the background. For the shot labeled “springing the trap,” the camera is again at a lower position, similar to the height of Point A, but still further to Gardner’s left (Point C), again with the dome of the Capitol in the background. Gardner’s framing of these last shots is not subtle.

Plan of the Old Capitol Prison, showing the approximate positions of Gardner’s camera during the Wirz execution sequence. The plan is undated (from here), but shows the facility during its use as a prison during and immediately after the Civil War, 1861-67.

After looking closely at these images, though, I believe that these last two are transposed chronologically; the third image, labeled “springing the trap,” is properly the last image in sequence, and shows Wirz’ body being lowered from gallows into the space below the scaffold. The evidence – and somewhat graphic images of the hanging – after the jump:

First Sergeant Henry, Is that You?

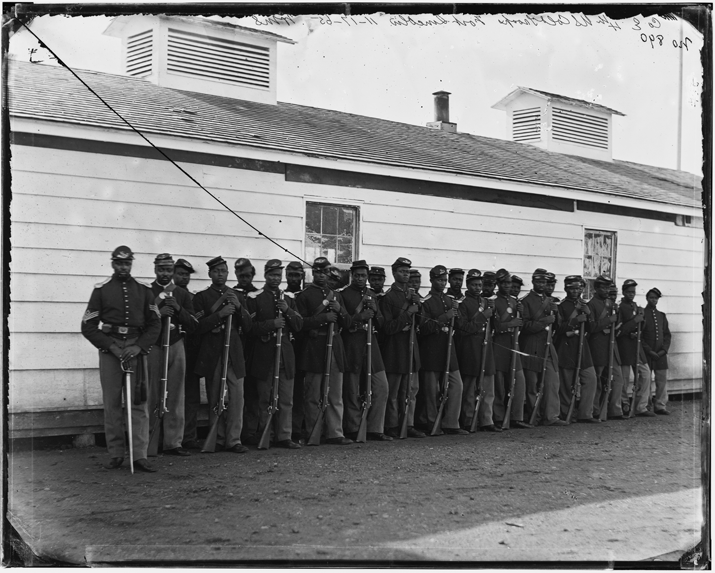

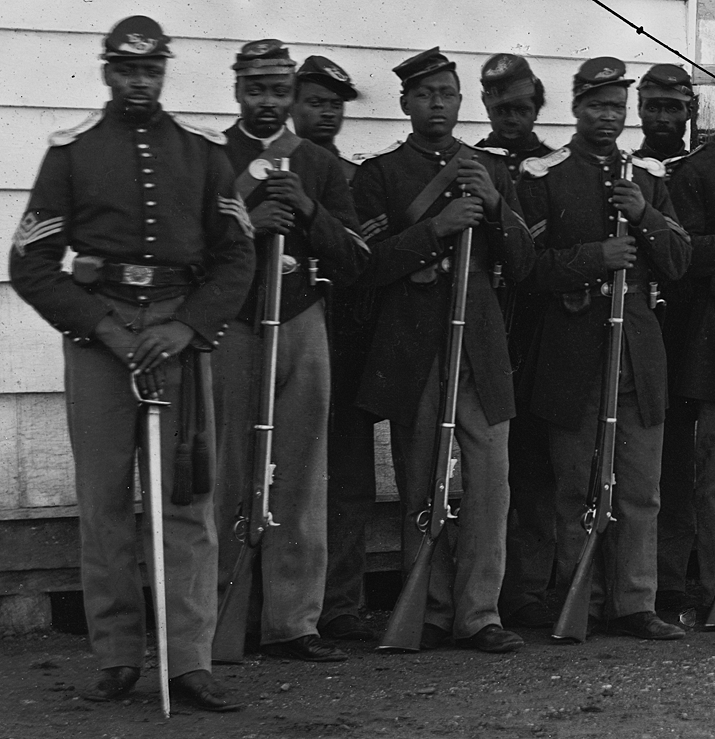

You’ve seen this picture a hundred times.

It appears in almost every book and article about African Americans serving in the Union Army, and on blogs dedicated to the subject. I’ve even used it here, myself. It’s an image of Company E, 4th U.S. Colored Infantry. I’d always guessed that this image was taken early in the 4th’s history, perhaps during its training phase; the uniforms and equipment (including polished shoulder scales) seemed too pristine, too precisely-placed (below). These are, I decided, garrisoned soldiers, not men who’ve been spending their time recently on the march or living in the field.

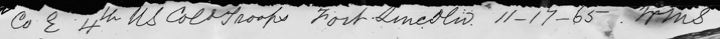

My reasoning was right, but my conclusion about the date was wrong. The image was not made during the 4th USCT’s working-up period. On the upper edge of the full image, available from the Library of Congress, the notation is scratched on the glass plate negative reads, “Co E 4th US Col’d Troops Fort Lincoln 11-17-65. WMS [William Morris Smith, the photographer].”:

It’s a postwar image, taken seven months after Appomattox. So they are garrisoned troops, well rested, in fresh uniforms and accoutrements. But they’re probably also all combat veterans, of hard-fought actions at Petersburg, Chaffin’s Farm/New Market Heights, and Fort Fisher. These men are not green recruits; they’re veterans, men who’ve seen some of the hardest fighting in the east in the last year of the conflict.

I had always guessed this image was a detachment of Co. E; in fact, it may be all of the enlisted men in Company E as it was at the end of the war.

We were discussing this image the other day at Coates’ blog, and I wondered if it was possible to identify any of the men in the image. There are twenty-seven men visible in the image; at least six of them are non-commissioned officers. It may be impossible to identify the others, but there should have been only a single First Sergeant on the company roster in November 1865; can he be identified?

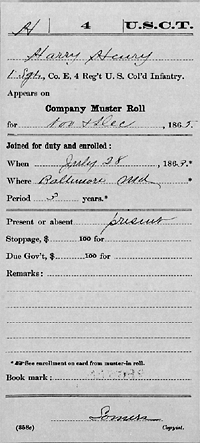

It’s actually a straightforward, two-step process. First, the NPS Soldiers & Sailors System database allows users to search by regiment, and pull up names of officers and enlisted men assigned to it. Helpfully, the database includes each soldier’s initial and final rank, so it’s a simple matter to identify a few likely candidates. Second, cross-check those men’s compiled service records via Footnote, to confirm each individual’s duty assignment and dates in rank. Using this method, it was quickly determined that in November 1865, the First Sergeant of Co. E, 4th USCT was First Sergeant Harry Henry. You can read his service record here, via Footnote (5.2MB PDF).

Locating a likely match in the NPS oldiers & Sailors System.

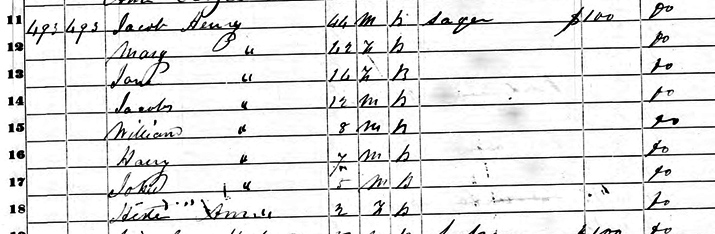

Harry Henry was born about 1842 on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. He was likely born free; he first appears in the 1850 U.S. Census, living with his father Jacob, a sawyer, and his wife, Mary, in or near Cambridge in Dorchester County. Harry was the third of at least six siblings; the others were Jane, born c. 1834; Jacob (Jr.), born c. 1838; William, born c. 1842; John, born c. 1845, and Ann, born c. 1848. At the time of the census, neither Jacob nor Mary could read or write, but Jacob held title to land valued at $100.

The Jacob and Mary Henry family in the 1850 U.S. Census.

By the time of the 1860 U.S. Census, most of the older children were no longer part of the household, but Harry, age 19, was still living with his parents and, like his father, earning his living as a sawyer. Ann, now aged 13, lived with them as well. As with the earlier census, none of the adults — now including Harry — were recorded as being able to read or write.

Harry Henry enlisted in Company E of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry at Baltimore on July 28, 1863, a few weeks after recruitment for the USCTs began. He enlisted for a term of three years. At the time he gave his age as 21 years, his height as five-foot-seven, with a “black” complexion, black eyes and curly hair. His occupation was listed as “farmer.” It appears that on that same day Harry’s older brothers, Jacob and William, enlisted in the same company. Jacob would be wounded at New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, but eventually return to duty. Jacob was apparently a crack shot, as he spent much of his enlistment on detached service, away from the regiment, with a sharpshooters’ unit. Both Jacob and William would survive the war and, with Harry, muster out of the 4th USCT as a Sergeant and Corporal respectively, in May 1866.

Henry was appointed Corporal at the time of his enlistment, but his service record carries few notations that give additional details of his service for his first year in the army. There are no notices of pay stoppage for lost gear, for example (a common entry for enlisted troops), nor notation of illness or injury. Beginning in July 1864, his pay records carry the notation, “free on or before April 19, 1861,” reflecting the army’s agreement to pay black soldiers the same as white, and to award the difference in back pay to those men who had been free before the outbreak of the war.

Sgt. Maj. Christian Fleetwood saves the 4th USCT’s colors at New Market Heights, September 29, 1864. Harry Henry’s brother Jacob was wounded in that action, and Co. E’s First Sergeant, Isaac Harroll, was killed. Image: “Field of Honor “by Joseph Umble, © County of Henrico, Virginia. Via The Sable Arm blog.

Company E’s original First Sergeant, Isaac Harroll, was killed at Chaffin’s Farm/New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, the same day Jacob Henry was wounded. Four other men of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, including Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood, would earn Medals of Honor in that action.The 4th took terrific casualties that day — 97 dead, 137 wounded and 14 missing.

Company E’s original First Sergeant, Isaac Harroll, was killed at Chaffin’s Farm/New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, the same day Jacob Henry was wounded. Four other men of the 4th U.S. Colored Infantry, including Sergeant Major Christian Fleetwood, would earn Medals of Honor in that action.The 4th took terrific casualties that day — 97 dead, 137 wounded and 14 missing.

Corporal Harry Henry was promoted to take Harroll’s place as First Sergeant of the company two weeks after the action, on October 14. He would remain First Sergeant of Company E for the remainder of the regiment’s time in service, including in November 1865 (right) when the famous photo was taken. There are few further notations describing his service through the end of the war; he mustered out with the regiment on May 4, 1866 in Washington, D.C.

I’ve found few solid leads on Harry Henry’s life after the war. There was a Harry Henry of about the right age living in Snow Hill, Maryland — about 40 miles from where the sawyer’s son Harry Henry had grown up — at the time of the 1900 U.S. Census. That later Harry Henry was married to a Sally M. Henry, age 51, with the notation that they’d been married for 35 years. It’s not certain, though, that these two Harry Henrys were in fact the same man. After 1900, the trail grows cold, and I really don’t know with certainty what became of Harry Henry after his discharge in 1866.

So that’s the circumstantial case for the man in the photo being Harry Henry. Does the photo itself yield any clues? Yes, it does.

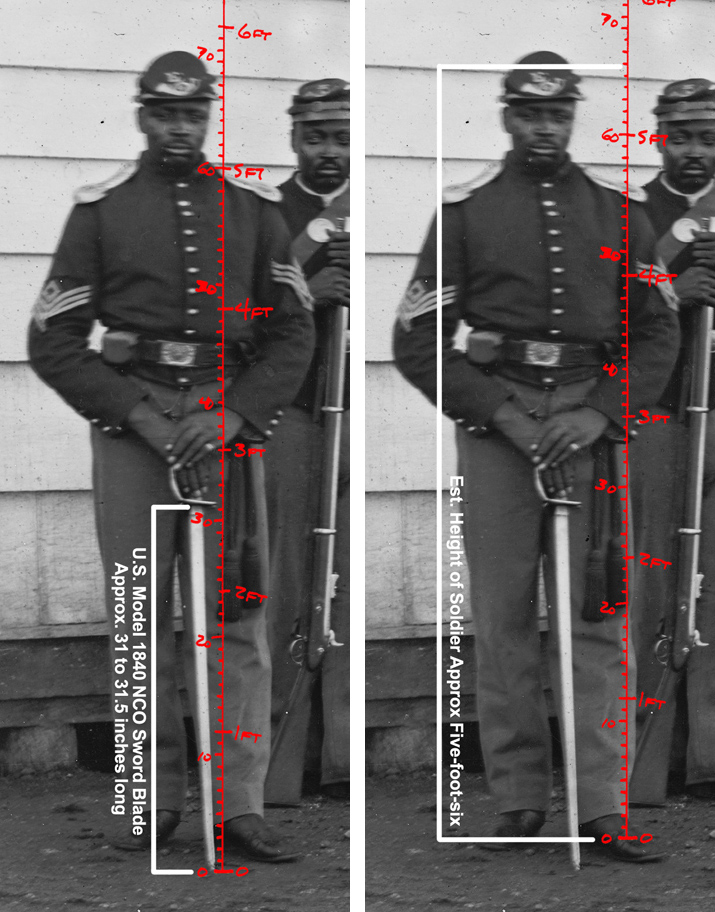

Looking at the overall image, the First Sergeant at first appears substantially taller than the other soldiers. But that could be a trick of perspective; he’s also closer to the camera than any of the others. Fortunately, he holds in his hands a tool we can use to estimate his height, what appears to be a U.S. M1840 Non-commissioned officer’s sword. The M1840 had a blade variously described as being between 31 and 31.5 inches long; because he’s holding it close to the vertical, we can use that blade as a rough scale to determine the First Sergeant’s height.

At left, a six-foot scale has been aligned and adjusted to match the blade on the sword. (The left side of the scale is marked in inches, the right in feet.) At right, that same scale has been moved to align with the approximate location of the bottom of the man’s heel. The scale suggests the man’s overall height at around five-foot-six, very close to Henry’s recorded height of five-foot-seven. While this estimate is only approximate — neither the bottom of the man’s foot not the top of his head are visible — it’s very consistent with the man in the image being Harry Henry.

Can we definitively prove that the First Sergeant in the famous photo is Harry Henry? No. But both the documentary record and careful analysis of the photo suggest strongly that it is.

If anyone out there has additional information on Harry Henry, either his service with the 4th USCT or his life afterwards, I’d love to know it.

______________

For the Ferroequinologists

Over at the Civil War Picket, Phil Gast mentions a proposal that would (sort of) reunite the Texas and the General, engines made famous in the “Great Locomotive Chase” in 1862. From the linked news item:

In celebration of the 150th anniversary of the Civil War, [Marietta, Georgia Mayor Steve] Tumlin said he’d like to display The Texas across the tracks from the historic Kennesaw House, in a parking lot managed by the Downtown Marietta Development Authority, or nearby.

Tumlin is asking the council to pass a resolution to make inquiries with the state, city of Atlanta and Cobb Legislative Delegation about a possible relocation of The Texas to Marietta, whether permanent or temporary. . . .

The General is now housed in The Southern Museum in Kennesaw.

Camille Russell Love, director of cultural affairs for the city of Atlanta, said The Texas is owned by Atlanta. It was moved to Atlanta’s Grant Park in 1911 and moved into the Cyclorama building in 1927, when that building was under construction.

Love, who is in charge of the Cyclorama, said no one has contacted her about moving the steam engine.

“My first question would be how could they get it out? Someone would have to dismantle the building,” she said.

Yeah, there are a few minor details to work through.

The proposed Texas locomotive display area (red shading) in Marietta, between the Kennesaw House museum and the dumpsters behind the Krystal Burger drive-thru. At upper right on the corner (black sign) is the Gone with the Wind Movie Museum. Why, fiddle-de-dee!

It would be six different kinds of awesome to have those two locomotives together, but it’s pretty silly to move one, now miles away from the other, to a site slightly fewer miles away from the other. And the notion of putting a 155-year-old locomotive out in the weather — even under cover — should be a non-starter. It’s a big, heavy artifact, to be sure, but it’s still an artifact, and not replaceable. The pair need to be displayed together; if you’re going to put the Texas in a parking lot behind a burger joint, you might as well leave it in Atlanta. These locomotives both should be carefully preserved and interpreted, to inspire future Civil War bloggers as they’ve done for generations. For their part, I can’t imagine why Atlanta would want to give up the Texas. This really sounds like an idea that needs to incubate a while longer.

In the meantime, Friday is always a good day for Buster Keaton:

In other news, the good folks over at the League of Ordinary Gentlemen asked about cross-posting Thursday’s piece on Confederate soldiers and the prevalence of slaveholding. Those guys are a smart, eclectic bunch, and I’m honored to share a little electronic real estate with them. I wear 7¼ in a bowler, thanks.

Dead Confederates recently passed 1,000 comments. Thanks to all of you who take time to write, and thanks especially for keeping things (mostly) civil. Given the consternation my writing seems to cause in some quarters, y’all may be surprised to know that in the nearly-a-year this blog has been online, I’ve only had to drop the ban-hammer on two parties. I’d like to think of that as a success.

Everybody have a great weekend, and keep the people of those areas devastated by tornadoes, particularly Alabama, in your thoughts and prayers.

_______________

Image: “Confederates in Pursuit,” by Walton Taber. Yuh, I know the Texas ran in reverse during the chase. I still like the image.

2 comments