JSTOR’s Register-and-Read Program

JSTOR, the online database of academic journals and publishing, recently announced an expansion of its “Register and Read” program, which had previously been available in a trial version that included only a few dozen journals. Register and Read will allow users who sign up to access up to three articles from 1,200 journals, every two weeks. Articles can be read online, but a smaller number will be available for download, for an additional fee.

JSTOR, the online database of academic journals and publishing, recently announced an expansion of its “Register and Read” program, which had previously been available in a trial version that included only a few dozen journals. Register and Read will allow users who sign up to access up to three articles from 1,200 journals, every two weeks. Articles can be read online, but a smaller number will be available for download, for an additional fee.

For those used to using the regular JSTOR through an institution, or through an individual membership, these are fairly — no, very — severe limitations. But I can also see that for folks who have no access otherwise, who need a specific article or two, this new program might be very useful. Prospective users can download an Excel file listing the included journals here.

I’ve known and worked with a lot of academics in widely-divergent disciplines over the years, and I suspect they have mixed feelings about this move. Like everyone else who writes, whether it’s on a blog, or history, or fiction, or haiku, they all want more people to read their stuff, period. That’s all to the good.

On the other hand, the business model for academic journals is shaky already, heavily subsidized by universities paying tremendously-high subscription fees, and by charges dumped off on individual authors themselves (page fees, image reproduction fees, etc.) Making these same articles available to a wider audience, even on a small scale like the Register-and-Read program, isn’t going to make that situation any better, and may make it slightly worse.

It will be interesting to see what comes out of this.

__________

A Blue Norther

In the winter of 1843-44, an Englishwoman by the name of Matilda Charlotte Houstoun (pronounced “Haweston”) visited Galveston twice with her husband, a British cavalry officer. The Houstouns were making a tour of the Gulf of Mexico, with Captain Houstoun trying to drum up interest in an invention of his for preserving beef. During their second visit, the Houstouns made a trip to Houston and back the 111-ton steamer Dayton, Captain D. S. Kelsey. On the trip back, the little steamer was delayed for two nights at Morgan’s Point, at the head of Galveston Bay, because a “norther” had blown so much water from the bay that it was impossible for the boat to get over nearby Clopper’s Bar, until the water rose again. The passengers went ashore and occupied their time in various ways; Captain Houstoun managed to shoot a possum, which was a novel creature to him. It was an object of brief curiosity until other passengers, more familiar with the fauna of Texas, appropriated it for the cook with the assurance that the animal was “first rate eating.”

![]()

Morgan’s Point and Clopper’s Bar, as shown on an 1856 U.S. Coast Survey chart of Galveston Bay. The soundings are in feet; any unusual reduction in the water level in the bay would make the bar impassible.

Morgan’s Point and Clopper’s Bar, as shown on an 1856 U.S. Coast Survey chart of Galveston Bay. The soundings are in feet; any unusual reduction in the water level in the bay would make the bar impassible.

![]()

“Northers” were new phenomena to the Houstouns, too, and in her travelogue Matilda Charlotte Houstoun gave a fine description of one:

They most frequently occur after a few days of damp dull weather, and generally about once a fortnight. Their approach is known by a dark bank rising on the horizon, and gradually overspreading the heavens. The storm bursts forth with wonderful suddenness and tremendous violence and generally lasts forty-eight hours; the wind after that period veers round to the east and southward, and the storm gradually abates. During the continuance of a norther, the cold is intense, and the wind so penetrating, it is almost impossible to keep oneself warm.

![]()

We had a norther here last week, a weather front that blasted through the area on the night of Wednesday/Thursday, part of the same front that caused hideous and deadly dust storms on the South Plains in Lubbock earlier. Down here, over 500 miles away, it left an orange dusting on cars and houses. Driving down to Angleton in Brazoria County along the Gulf on Thursday afternoon, my vehicle was continually buffeted by 25- to 30 mph winds, and an occasional higher gust, at a right angle to the road, pushing the car to the left, toward oncoming lanes of traffic. Not real fun.

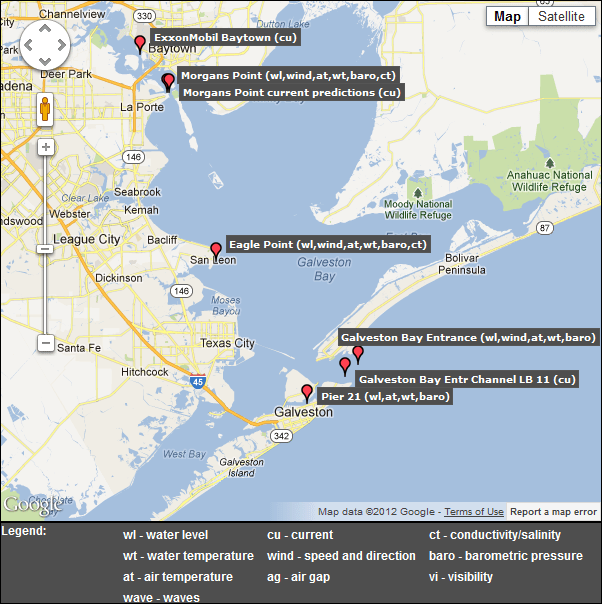

But the most interesting aspect of this is one experienced by the Houstouns and others aboard Dayton almost 170 years ago, the effect of this strong, steady wind on local water levels. Historical accounts of bad weather will often include phrases like “blew the water out of the bay,” or something similar, and that’s not much of an exaggeration. Late Thursday evening, almost 24 hours after the front went through, I collected some graphics of meteorological and hydrologic data from Houston/Galveston Bay PORTS, a reporting system built and maintained by NOAA to provide real-time updates of conditions for those in the maritime industry. The graphics are small and a little difficult to read, but they provide direct, measured documentation of the sort of event described by so many mariners and travelers over the years. The data presented here are drawn from three different locations: Morgan’s Point, where Mrs. Houstoun and Dayton were stranded for two days; Pier 21 at Galveston, at the site of what was then known as Central Wharf, the steamboat’s destination; and Galveston Bay Entrance, a buoy along the channel through which marine traffic enters and leaves all the ports in the region — Galveston, Texas City, Houston, Baytown, and so on:

![]()

![]()

Let’s look at the data in some detail:

![]()

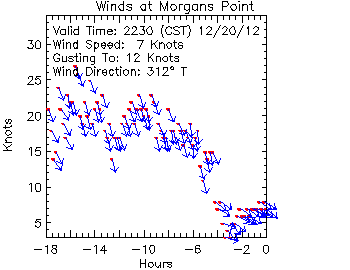

Wind speed at Morgan’s Point. This little chart shows the wind direction and speed for the period beginning about 4:30 a.m. on Thursday. The red dots show the sustained wind speed (scale on the y axis), while the blue arrows show its direction. For most of the period, right up until about 6 p.m., the wind blew steadily and consistently from the NNW at between 15 and 25 knots (17.3 to 28.8 mph), with gusts above that.

Wind speed at Morgan’s Point. This little chart shows the wind direction and speed for the period beginning about 4:30 a.m. on Thursday. The red dots show the sustained wind speed (scale on the y axis), while the blue arrows show its direction. For most of the period, right up until about 6 p.m., the wind blew steadily and consistently from the NNW at between 15 and 25 knots (17.3 to 28.8 mph), with gusts above that.

![]()

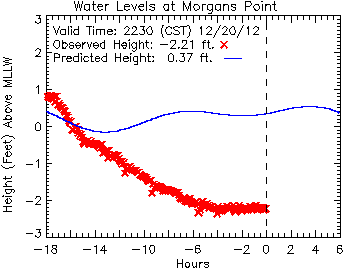

This chart shows the water levels at Morgan’s Point, from about 4:30 a.m. Thursday until late that evening. The narrow blue line represents the predicted height of the water at the tide gauge; it wavers a little bit based on the natural flow of the tide, which has a small normal range at that point. The red X marks are the actual, observed height of the water, which drops steadily with the wind over a period of about twelve hours, before leveling off and holding steady at more than two-and-a-half feet below the point known as “mean lower low water” (MLLW), the low-water standard that is used for navigational purposes. Note that the wind also wiped out almost any of the normal rise in the water level expected due to tidal action.

![]()

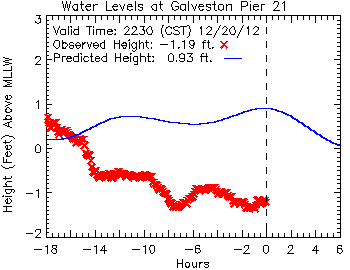

What about at the south end of Galveston Bay? Here’s the project vs. actual recorded water levels at Pier 21, along the Galveston wharf front:

![]()

Here, closer to the Galveston Bay entrance, tidal action has more effect, but the water level remains more than two feet lower than predicted.

Here, closer to the Galveston Bay entrance, tidal action has more effect, but the water level remains more than two feet lower than predicted.

![]()

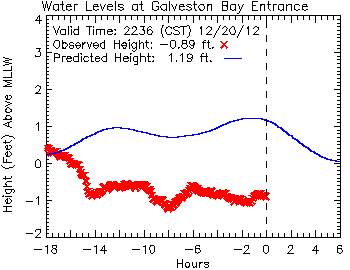

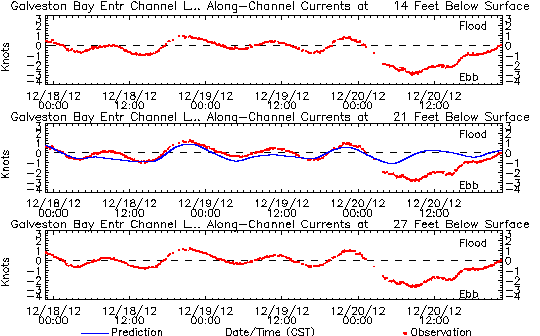

This chart, plotting data from a buoy at the entrance to the bay, reveals an almost identical profile to that from Pier 21. Here, again, eighteen hours after the passage of the front, the water remains more than two feet below its predicted level based on tides alone.

![]()

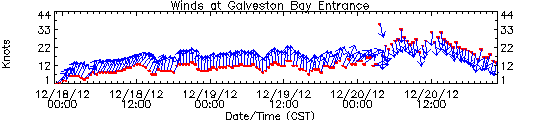

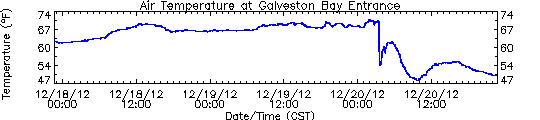

These three charts show (top to bottom) wind speed and direction, air temperature and water levels at the entrance to Galveston Bay, for a 72-hour period ending about 10:30 p.m. on Thursday. Comparing these, it’s easy to see when the front passes in the early morning hours of Thursday, prompting dramatic changes in the wind, air temperature and water levels.

These three charts show (top to bottom) wind speed and direction, air temperature and water levels at the entrance to Galveston Bay, for a 72-hour period ending about 10:30 p.m. on Thursday. Comparing these, it’s easy to see when the front passes in the early morning hours of Thursday, prompting dramatic changes in the wind, air temperature and water levels.

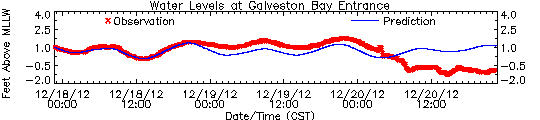

![]()

Finally, one last chart, showing the sub-surface currents at the entrance to Galveston Bay, at 14, 21 and 27 feet (4.3, 6.4 and 8.2 meters) below the surface. You can see the normal tide effect for the first 48 hours on this chart, as the current shifts between a flood tide (above the dashed line, water going into the bay), and an ebb tide (below the dashed line) as it flows out again. Although the wind only acts on the surface of the water directly, the momentum it generates there is carried through into much deeper water, dramatically altering flow of water so much that even at a depth of 27 feet, the normal tidal action is so completely erased that it results in a net ebb of the tide, a full eighteen hours of water emptying from Galveston Bay into the Gulf of Mexico.

Finally, one last chart, showing the sub-surface currents at the entrance to Galveston Bay, at 14, 21 and 27 feet (4.3, 6.4 and 8.2 meters) below the surface. You can see the normal tide effect for the first 48 hours on this chart, as the current shifts between a flood tide (above the dashed line, water going into the bay), and an ebb tide (below the dashed line) as it flows out again. Although the wind only acts on the surface of the water directly, the momentum it generates there is carried through into much deeper water, dramatically altering flow of water so much that even at a depth of 27 feet, the normal tidal action is so completely erased that it results in a net ebb of the tide, a full eighteen hours of water emptying from Galveston Bay into the Gulf of Mexico.

![]()

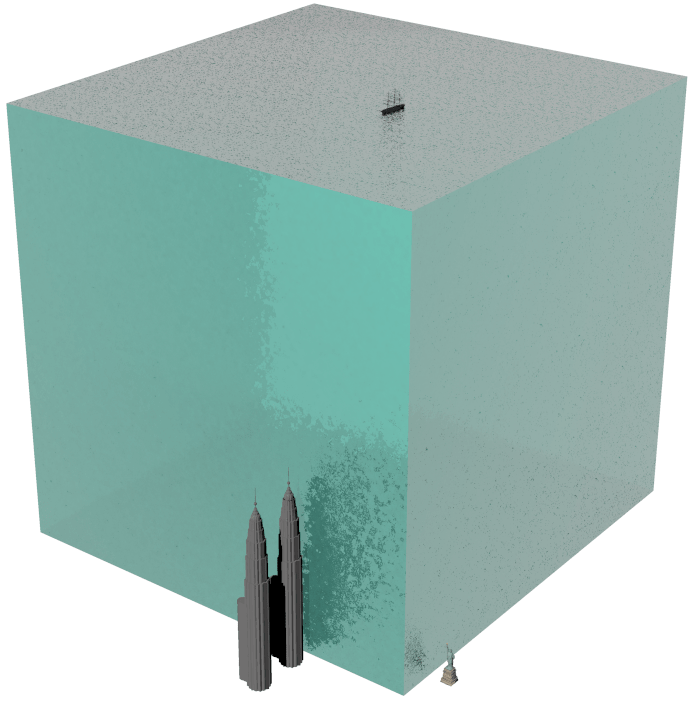

How much water got “blown out of the bay” on this occasion? Some (very) rough estimates are possible. (Check my math, y’all.) If we take the difference between the predicted and observed water levels at the head of the bay (Morgan’s Point, -2.57 feet) and entrance to the bay (Galveston Bay Entrance, -2.08 feet), we can average between them a value of -2.33 feet. If we take that figure as representative of the water level of the bay as a whole (and that’s a big “if,” admittedly), then we can convert that vertical dimension into the volume of water it represents.

Galveston Bay encompasses about 600 square statute miles. One square mile is 27.88 million square feet; 600 square miles is 16.73 billion square feet. Multiply that by a depth of 2.33 feet, and you get a total volume of water of 38.98 billion cubic feet (1.1 billion cubic meters) of water.

That’s a lot of water; it would fill a cube-shaped aquarium 3,390 feet (1,033 meters), over a half-mile long, on each side. The water would weigh something on the order of 1.24 billion short tons, or 1.13 billion metric tonnes.

![]()

A 3,390-foot cube of seawater, approximating the volume of water blown out of Galveston Bay during the norther on December 20, 2012. Shown to scale are (top) a large, full-rigged sailing ship similar to Cutty Sark, (right) the statue of Liberty, and (left) the Petronas Towers in Malaysia, among the world’s tallest structures.

A 3,390-foot cube of seawater, approximating the volume of water blown out of Galveston Bay during the norther on December 20, 2012. Shown to scale are (top) a large, full-rigged sailing ship similar to Cutty Sark, (right) the statue of Liberty, and (left) the Petronas Towers in Malaysia, among the world’s tallest structures.

![]()

So much for the numbers. What does this mean in practical terms for navigation on Galveston Bay? Today, weather conditions like these still pose a problem, particularly the wind, which poses significant challenges for large vessels transiting the Houston Ship Channel. I suspect the problem is worse for down-bound vessels than up-bound, as the former are running with the wind and current, and are thus much more difficult to maneuver.

In the mid-19th century, the challenges of foul weather on the bay were substantially worse. The riverboats that ran between Galveston and Buffalo Bayou, Cedar Bayou, or the mouth of the Trinity River were very vulnerable, with their high superstructures and chimneys to catch the wind from any angle. (The little sternwheeler C. K. Hall, carrying a load of bricks out of Cedar Bayou, was sunk in just such a situation in 1871.) But the bigger problem then, before major dredging operations had established a deep and stable channel, was the depth of water over obstacles like Clopper’s Bar and Red Fish Bar, a nine-mile-long oyster reef curving in a gentle, east-west arc stretching completely across Galveston Bay, almost exactly halfway between Clopper’s Bar and Galveston Island. Red Fish Bar could, on occasion, cause significant damage to vessels, and at least one steamboat, Ellen P. Frankland, would be wrecked on the obstruction in the 1840s. Both Clopper’s Bar and Red Fish Bar could be crossed regularly by vessels drawing less than four feet, but this depth of water varied with the tide and weather.

![]()

Red Fish Bar, as shown on an 1856 chart of Galveston Bay. Soundings are given in feet.

Red Fish Bar, as shown on an 1856 chart of Galveston Bay. Soundings are given in feet.

![]()

I doubt that most of us in this area paid too much attention to the weather Thursday, apart from the inconvenience of the sudden drop in temperature and the wind. But it’s good to keep in mind how dramatically similar events sometimes affected the day-to-day lives of people in the past, and how fortunate we are to be sometimes that much more removed from them.

_____________

Moving the Big Guns on Alabama

Over at Civil War Talk, there was an inquiry as to how the big, mounted artillery on ships like Alabama were moved about. When you look at a model or drawing of a CW-era ship, the deck often seems to be covered with metal arcs, obviously related to moving the gun, but in no clear pattern that’s easy to discern. (See this example on a model of U.S.S. Kearsarge.)Fortunately, Andrew Bowcock covers this procedure in some detail in his C.S.S. Alabama: Anatomy of a Confederate Raider. Although he described the procedure for a specific gun on that vessel, the process would be similar on other ships.

There are three basic components to the gun — the tube, the carriage on which the tube is mounted, and the slide in which the carriage was run forward and back (with recoil). It’s the arrangement of the slide here that’s important. The key to the whole process is that each end of the slide is fitted with a hole through which a brass pivot pin could be dropped, going through the carriage and into a matching, iron-reinforced hole in the deck. The key to shifting the gun from one position to another was to swing the slide on one pivot to line up the pivot hole at the other end with another point, put that pin in place, remove the first pin, and then swing the whole thing from the other end. It sounds complicated, but it is practical and (relatively) safe on a rolling deck, since the slide will (at worst) swing in an arc, rather than go barreling across the deck like a loose gun on trucks.

Here is a diagram of the eight pivot positions (marked in red) used for Alabama’s aft 8-inch smoothbore pivot — the one Captain Semmes was famously photographed with:

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/pivotpoints.jpg?w=720)

And this shows the pivot points on the slide for that gun:

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/pivots.jpg?w=720)

And here is that process illustrated on the digital model:

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/position-01.jpg?w=720)

Gun positioned on center-line of deck, normal stowed position.

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/position-02.jpg?w=720)

Back end of slide is swung to an intermediate pivot point on the port side and pinned there.

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/position-03.jpg?w=720)

Front end of the slide in unpinned and swung toward the port side.

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/position-04.jpg?w=720)

The swing complete, the forward end of the slide in pinned at the ship’s side, and the back end in unpinned to allow the back end of the slide to swing freely.

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/position-05.jpg?w=720)

The gun is now ready for action.

The model is simplified for clarity, and omits all the block-and-tackle, breeching ropes, and the dozen or more crew members required to provide the muscle power to do this. (Bowcock notes that the official complement to work this gun in action would be sixteen men.) Anyway, I hope this makes the process a little clearer.

____________

Memo to the Union Pacific: You Didn’t Build That

Tuesday’s Houston Chronicle has a story about Navasota, a small town northwest of Houston, being listed in Union Pacific’s Train Town USA Registry. From the railroad:

Navasota will receive an official Train Town USA resolution signed by Union Pacific Chairman Jim Young, and Navasota’s historical connection with Union Pacific will be featured at www.up150.com. “We are proud to recognize Navasota as we commemorate our railroad’s sesquicentennial celebration and growing up together,” said Joe Adams, Union Pacific vice president – Public Affairs. “The bond between our railroad and early settlements continues to strengthen and grow. Today, Union Pacific serves nearly 7,300 communities where we live, our children grow up together and in which we recruit employees. “Our shared heritage with Navasota is a source of pride as we remember our past while serving and connecting our nation for years to come.” The railroad was essential to the birth of Navasota, which brought in major trade and market centers for cotton and livestock. Union Pacific laid 44 miles of track in 1902 to connect Navasota and Madisonville, Texas, and the town declared it a holiday when the first train departed to Madisonville. The line runs through historic downtown on Railroad Street and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. Today, Union Pacific works with the City of Navasota to create and maintain a landscaped area along Railroad Street, which brings heavy tourism, economic development and future infrastructure projects to the area.

Navasota absolutely is a railroad town, and I’m happy they were awarded this distinction. I hope Navasota Mayor Bert Miller, the city administration and the local chamber of commerce play this for all it’s worth, and can bring in a few extra tourist dollars as a result. That’s all to the good.

But contrary to the narrative suggested by the UP press release, that railroad had precious little to do with either Navasota’s creation or its establishment as a railroad town. Navasota was founded as a settlement in 1854, and in September 1859 was reached by the Houston & Texas Central, which extended just a few miles farther to Millican by the outbreak of the Civil War. The H&TC expanded rapidly after the war, north to the edge of Indian Territory and west to Austin. In 1876-77 the Morgan Line bought controlling interest in the H&TC, only to be itself absorbed into the Southern Pacific in the 1880s. The H&TC continued to operate under its own name until 1927, though — almost seventy years after it first put down rails in Navasota, and a full quarter-century after the UP completed its spur line to Navasota from Madisonville. The UP didn’t take over the Southern Pacific until 1998, fourteen years ago — less than one-tenth the time that Navasota has been a railroad town.

Houston & Texas Central locomotive W. R. Baker, c. 1868. Lawrence T. Jones III Collection of Texas Photographs, Southern Methodist University.

To be sure, I’m not a disinterested observer in this. My grandparents lived in Navasota for 40 years, and my father grew up there. When I was little, we lived nearby, and I spent a lot of time in Navasota. Even though I’ve never lived there myself, it’s a town I feel like I know, and feel a certain ownership in it. And on the other side of my family, I have a relative — a Confederate veteran, in fact — whose home was at Navasota during the war, and who took a job in 1865 as a brakeman on the H&TC. He eventually rose to be Superintendent of one of the railroad’s divisions, and finally, was General Agent for Transportation for the H&TC.

So it’s not for no reason that I find this award, ostensibly celebrating the rail history of Navasota, that doesn’t actually acknowledge the rail history of Navasota, just a little irksome.

![]()

Navasota mayor Bert Miller holds a sign announcing the city’s recent membership into Union Pacific’s Train Town USA Registry. Photo By Michael Paulsen/Houston Chronicle.

___________

The Sabine Pass Beacon

![]()

The newest issue of the Sabine Pass Beacon is available for download here. This issue includes a great story on the research and artifact conservation of one of the Federal gunboat U.S.S. Clifton‘s most distinctive features, the “walking beam” of its steam engine.

________________

New Feature for the Civil War Soldiers & Sailors Database

One of the most consistently useful online research tools available for Civil War folks is the National Park Service’s Civil War Soldiers & Sailors (CWSS) database. It has a number of features, but the most important is the database of soldier’s names and units, which can be searched a number of ways. If you’re looking for a specific Civil War soldier, it really is the place to start before going on to more in-depth primary sources, like the national Archives’ compiled service records (CSRs) at subscription sites like Fold3. One nice aspect of the NPS database is that it seems to be drawn from the CSRs at the National Archives (Mike, is this correct?), which means that if you find an entry in the database, there should be ay least something at NARA. As I say, it really is the place to start.

One of the most consistently useful online research tools available for Civil War folks is the National Park Service’s Civil War Soldiers & Sailors (CWSS) database. It has a number of features, but the most important is the database of soldier’s names and units, which can be searched a number of ways. If you’re looking for a specific Civil War soldier, it really is the place to start before going on to more in-depth primary sources, like the national Archives’ compiled service records (CSRs) at subscription sites like Fold3. One nice aspect of the NPS database is that it seems to be drawn from the CSRs at the National Archives (Mike, is this correct?), which means that if you find an entry in the database, there should be ay least something at NARA. As I say, it really is the place to start.

1940 Census Update

As many of you know, Ancestry recently added the enumeration pages from the 1940 U.S. Census to its website. (The same files can be viewed for free at the National Archives, here.) Indexing the several million pages by name, however, is going to take much longer — months, at least — so it will be a while before users can simply type in a name and find the person they’re looking for, anywhere in the country. For now, you have to start looking by location.

If you know the street address you’re looking for, though, there’s a handy tool available here, developed by two census researchers, Stephen P. Morse and Joel D. Weintraub, that lets users identify the specific enumeration district, which can then be accessed through Ancestry. You’ll still have to look through a number of pages of enumeration rolls, but it’s a heck of a lot easier than going by-guess-and-by-golly.

I looked up several addresses that are of interest to me in this way, and it worked pretty well. I looked up my own address and found who was living in my house 72 years ago. We’d always known what family it was, but it was interesting to see who was actually present, living in the house at that time.

What unexpected discoveries have you found in the 1940 census?

_____________From the original caption: “Herman Hollerith invented a ‘unit tabulator,’ shown on left of photo being operated by Operator Ann Oliver. This machine is fed cards containing census information at the rate of 400 a minute and from these, 12 separate bits of statistical information is extracted. Not so long ago, Eugene M. La Boiteaux, Census Bureau inventor, turned out a smaller, more compact machine, which extracts 58 statistics from 150 cards per minute. This machine is shown on the right and is being operated by Virginia Balinger, Assistant Supervisor of the current Inquiry Section. With the aid of this machine, statistical information from the 1940 census is expected to be compiled in 2 1/2 years.” Library of Congress.

C.S.S. Georgia to be Excavated

Good news on the nautical archaeology front, in that the wreck of C.S.S. Georgia, and ironclad battery deployed to protect the city of Savannah, will be excavated and preserved as part of the $653M harbor improvement program. The cost of the excavation and conservation is estimated to be around $14M, or just over 2% of the total project cost.

Georgia was originally intended as an ironclad warship, but a lack of suitable powerplant — the bane of Confederate casemate ironclads from Virginia on — resulted in her being moored as a floating battery instead. In twenty months of service she never fired a shot in anger, but would have been a formidable opponent had the Union navy tried to force the port as they did at Charleston, Mobile, and elsewhere. The battery was scuttled by her crew just before Christmas 1864 just as Sherman was poised to seize the city at the end of his “March to the Sea.” You can read more about C.S.S. Georgia here.

Location of the wreck of C.S.S. Georgia (gold ring), opposite Old Fort Jackson.

Photo by Mike Stroud (via To the Sound of the Guns) of a 32-pound banded rifle recovered from the wreck of C.S.S. Georgia, displayed on a reproduction carriage at Fort Jackson.

I saw a comment about this story in which someone snarked, “the Confederate Navy still continues to hinder the US Navy.” Funny, but inaccurate, as the U.S. Navy (through the Naval Historical Center) generally provides a lot of encouragement and guidance when it comes to wrecks like this. (All former Confederate government property transferred to the United States at the end of the war, so former Confederate vessels like Georgia and the famous C.S.S. Alabama are now considered U.S. Navy property, and under their stewardship.) The problem is, the Navy doesn’t have the resources to undertake expensive work like this, and has to rely on other agencies that do have budgets for them, to get the actual work done.

It’s also worth noting that the reason this work is being undertaken at all is because of federal laws that require investigation, assessment, and (in some cases) archaeological recovery of significant historical/cultural material that lies on public land, that would be disturbed or destroyed by development or construction. Most states have similar laws. What will be done in this case is very much like the U.S.S. Westfield Project in Texas, although (I gather) with a bigger budget and the prospect of recovering significant parts of the ship’s structure intact. Without those preservation laws, wrecks like C.S.S. Georgia would’ve been reduced to soggy toothpicks by dredging many years since.

____________

Image: (top) Naval Historical Center; (bottom) 32-pounder image by Mike Stroud, via To the Sound of the Guns

“Disgusting treachery and negligence”

Today is the sesquicentennial of one of the most audacious acts of the Civil War, when Robert Smalls, an enslaved African American trained as a harbor pilot, took his vessel out the Union blockading fleet off Charleston. It’s already been mentioned several places, with due credit to Smalls and his comrades. As Union Admiral David Dixon Porter put it in his naval history of the war, “this required the greatest heroism, for had he been caught while leaving the wharf, or stopped by the forts, he would have paid the penalty with his life.” More on Smalls and Charleston here.

So given the coverage Smalls’ actions will get — and rightly so — I thought it would be interesting to see the coverage from the other side, from the perspective of Confederate Charleston. Here, from the Charleston Mercury, May 14, 1862:

DISGUSTING TREACHERY AND NEGLIGENCE Yesterday, at daylight, the steamer Planter, in the absence of her officers, was taken by four or five of her colored crew from her berth at Southern Wharf, to the enemy’s fleet. She is a high pressure cotton boat, of light draught, formerly plying on the Pee Dee River, but latterly chartered by the Government, with her officers and crew, from Mr. Ferguson, her owner, and used as a transport and guard boat about the harbor of Charleston. Her armament was a 32-pounder and a 24-pound howitzer. The evening previous she had taken aboard four guns for one of the newly erected works, either that on Morris Island or Fort Timber, viz., a 42-pounder rifled and banded, an 8-inch columbiad, both of which had been struck at the reduction of Ft. Sumter, and 8-inch seacoast howitzer, and a 32-pounder. These guns were to have gone to their destinations early in the morning, and been mounted yesterday. Three sentinels were stationed in sight of her, and a detail of twenty men were within hail for the relief of the post. Between half-past three and four o’clock the Planter steamed up and cast loose, the sentinels having no suspicion of foul play, and thinking she was going about her business. At quarter past four o’clock she passed Fort Sumter, blowing her whistle, and plainly seen. She was reported by the Corporal of the Guard as the guard boat, to the Officer of the Day, Captain Flemming, one of the best and most reliable officers of the garrison. The fort is only called on to recognize authorized boats passing, taking for granted that they have their officers aboard. This was done as usual. The run to Morris Island goes a long way out past the fort, and then turns. The Planter on this trip did not turn. The officers of the Planter were [Charles J.] Relyea, Captain; Smith, Mate; and Pitcher, Engineer. They have been arrested, and will, we learn, be tried by court-martial for disobedience of a standing general order, that the officers and crews of all light draught steamers in the employment of the Government will remain on board day and night. The result of this negligence may be only the loss of the guns and of the boat, desirable for transportation. But things of this kind are sometimes of incalculable injury. The lives and property of this whole community are at stake, and might be jeopardized by event apparently as trifling as this. It ism therefore, due to the Service and to the Cause, that this breach of discipline, however innocent in intention on the part of the officers, should be dealt with as it deserves. Without strict discipline, no military operations can succeed.

Note that the black men who stole the boat get only a passing mention; virtually the entire piece focuses on the incompetence and negligence on the part of Confederate authorities in letting them get away with it. There’s no surprise expressed that Smalls and his companions would attempt to take the boat, so much as shock that they were able to pull it off. The newspaper story makes no hint of a betrayed assumption of loyalty on the part Planter‘s enslaved crew members to either their owners, or to the Confederate cause.

The newspaper got the name of the ship’s mate wrong; he was not “Smith,” but John Smith Hancock. He, Engineer S. Z. Pitcher, and Captain Relyea, went to trial; Relyea and Hancock were both found guilty. Relyea was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment and a $500 fine, which if he did not pay would be commuted into a sentence of two additional months. Hancock was sentenced to one month in prison and a $100 fine. Engineer Pitcher argued “in bar of trial” that the charges were vague and insufficient, and after careful deliberation the charges against him were voided.

In his review of the court martial, however, Major General John C. Pemberton, commanding the Confederate Department of South Carolina and Georgia, overturned the convictions of Relyea and Hancock, noting that Planter‘s owner, Ferguson, “seems to have been entirely deficient as to the deportment of his subordinates.” Pemberton found that while Relyea and Hancock were in violation of general orders, “it is not clearly shown that General Order No. 5, referred to in the specification of the charges, had ever been properly communicated to Captain Relyea, or Hancock, the mate, nor do any measures appear to have been taken by their superiors to force an habitual compliance with the requirements of those orders” (Charleston Mercury, August 1, 1862). Relyea and Hancock were released.

I’ve read online that Captain Relyea was lost at sea between Charleston and Nassau in 1864, suggesting that he got involved in blockade running. Not sure if that’s true, but he left behind a spectacular, gold-headed cane of his that was sold twice last year at auction.

_______________

Come On, Texas!

On Saturday I had the opportunity to take a “hard-hat” tour of U.S.S. Texas (BB-35), which is preserved as a museum ship at the San Jacinto Battleground, near Houston. She’s one-of-a-kind, the last dreadnought battleship from the first great arms race of the 20th century. The tour was arranged by my colleague, Amy Borgens, for the benefit of the Marine Archaeological Stewards group. The tour was led by Ship Manager Andy Smith and the ship’s Curator, Travis Davis. There’s not very much about Texas that one or the other of those men doesn’t know.

It was quite remarkable, and I would urge anyone with a particular interest in technology or maritime history to take a similar tour if you can. Though the focus was mostly on the technology of the ship — structure, fittings and operation –there were quite a few very human touches, like personal locker whose owner had made a careful running account, inside the door, of all the other Texas sailors who owed him money. It was a long list. One of our group, a Navy veteran himself, commented that “there’s a guy like that in every division.”

The ship desperately needs a major overhaul and rebuilding of specific areas. There’s a significant amount of money set aside for this work already, but it’s not likely to be enough given the scale of the task, and plans are still being made to see how best to tackle the ship’s restoration and preservation with the resources available. As Ship Manager Andy Smith explained, it’s a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem. It’s hard to raise money without very concrete, specific plans as to how you’re going to spend it; at the same time, though, it’s hard to make detailed and pragmatic plans if you don’t know how much money you’re going to have to work with.

“Come on, Texas!” was a cheer her sailors used when rooting for their messmates in athletic competitions with other ships in the fleet, and it seems appropriate for this stage in the ship’s life, as well. In a few days, on May 18, 2012, U.S.S. Texas will mark her 100th birthday. Here’s hoping she’s still around for her 200th.

This diagram shows the locations appearing in the following images, roughly in order from aft (left), moving forward. More pictures after the jump:

2 comments