Into Action Aboard a Monitor at Charleston

Crew members aboard U.S.S. Nahant, one of the last surviving Civil War monitors, pose on deck for a photograph during the Spanish-American War in 1898. The dents in the turret behind them were put there by Confederate shot off Charleston, thirty-five years before.

One hundred fifty years ago Sunday afternoon, warships of the Union’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron steamed into Charleston harbor, intent on pounding Fort Sumter into submission. The U.S. Navy’s commanding officer, Rear Admiral S. F. Du Pont (right), had at his disposal two full divisions of ironclad monitors that, he hoped, would be able to stand up against the Confederate batteries ringing the harbor. But the Confederate fire was too great, most of Du Pont’s ships were seriously damaged in the action. After about ninety minutes’ hard action, the Union fleet withdrew. In his report to the Navy Department, Du Pont described the event as a “failure,” but saw his withdrawal as one that had averted what otherwise would have been a “disaster.”[1]

One hundred fifty years ago Sunday afternoon, warships of the Union’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron steamed into Charleston harbor, intent on pounding Fort Sumter into submission. The U.S. Navy’s commanding officer, Rear Admiral S. F. Du Pont (right), had at his disposal two full divisions of ironclad monitors that, he hoped, would be able to stand up against the Confederate batteries ringing the harbor. But the Confederate fire was too great, most of Du Pont’s ships were seriously damaged in the action. After about ninety minutes’ hard action, the Union fleet withdrew. In his report to the Navy Department, Du Pont described the event as a “failure,” but saw his withdrawal as one that had averted what otherwise would have been a “disaster.”[1]

Since we’ve talked a good bit about Civil War-era monitors here, I’d like to share an account of this action by Alvah Folsom Hunter (1846-1933), a sixteen-year-old ship’s boy aboard one of those monitors, U.S.S. Nahant. Hunter had been in the Navy only a few months, and recorded his experiences aboard Nahant in great detail. An annotated edition of Hunter’s diary was published in 1987, edited Craig Symonds.[2] Most of the drawings that accompany Hunter’s account here are by one of his shipmates aboard Nahant, Assistant Surgeon Charles Ellery Stedman.

![]()

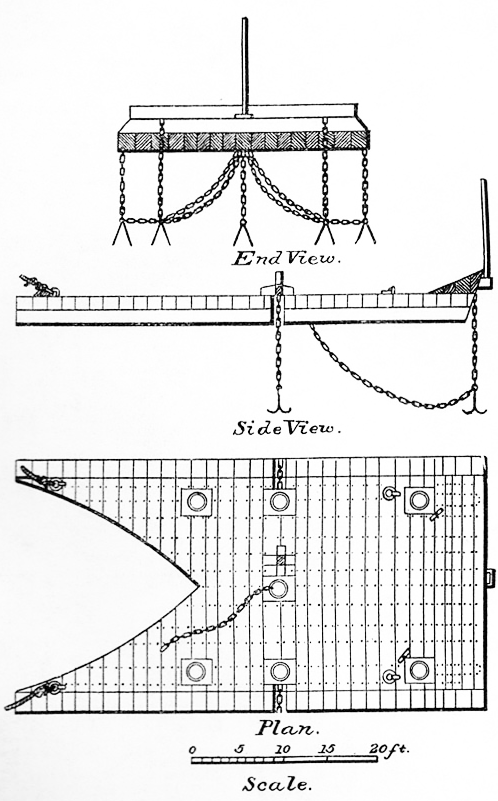

U.S.S. Weehawken’s “devil,” as depicted in the ORN.

U.S.S. Weehawken’s “devil,” as depicted in the ORN.

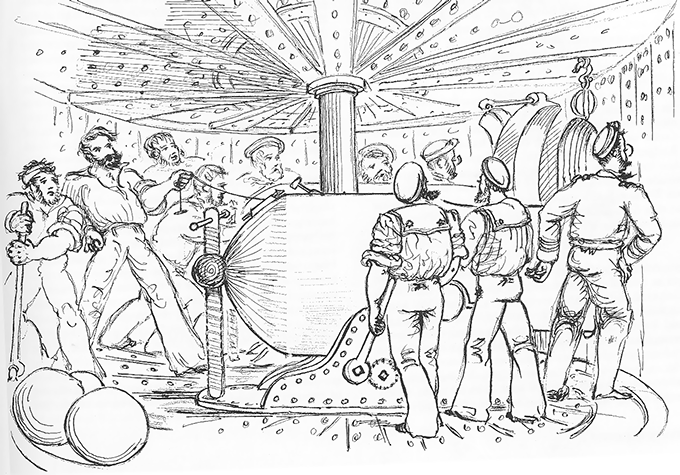

Handling ammunition in the compartment below the turret, by Nahant’s Ship’s Surgeon, C. E. Stedman.

Handling ammunition in the compartment below the turret, by Nahant’s Ship’s Surgeon, C. E. Stedman.

Stedman’s drawing of Nahant’s turret in action. Stedman omits much of the internal bracing used in the turret, but captures the action well.

Stedman’s drawing of Nahant’s turret in action. Stedman omits much of the internal bracing used in the turret, but captures the action well.

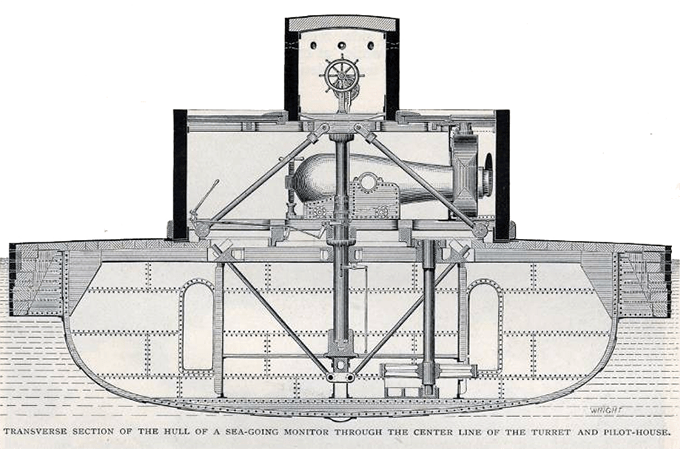

Cross-section through the hull, turret and pilothouse of a Civil War monitor similar to U.S.S. Nahant.

Cross-section through the hull, turret and pilothouse of a Civil War monitor similar to U.S.S. Nahant.

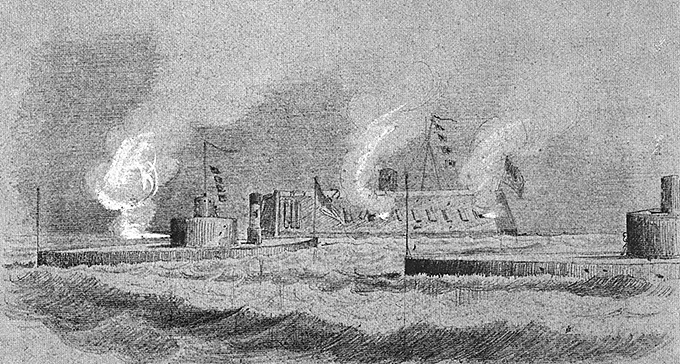

Stedman’s depiction of the action off Fort Sumter in April 1863, with (l. to r.) Nantucket, New Ironsides and Nahant. Stedman, as was his pratice at the time, gave the first and last of these vessels the fictional names of “Otternel” and Semantecook” in the caption of his drawing.

Stedman’s depiction of the action off Fort Sumter in April 1863, with (l. to r.) Nantucket, New Ironsides and Nahant. Stedman, as was his pratice at the time, gave the first and last of these vessels the fictional names of “Otternel” and Semantecook” in the caption of his drawing.

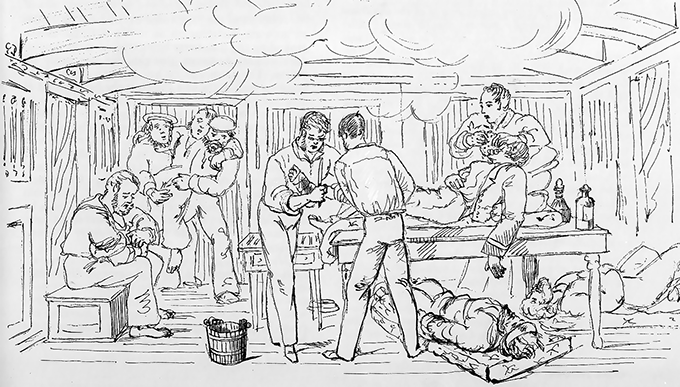

Treating casualties in action on the wardroom table, by Assistant Surgeon Stedman. This scene actually depicts his earlier ship, U.S.S. Huron.

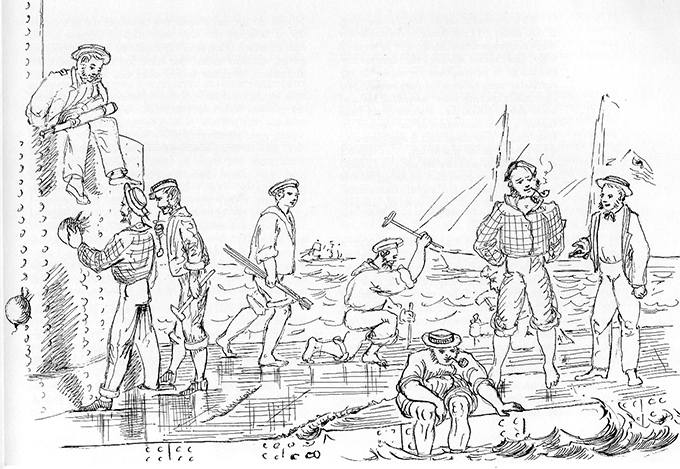

Stedman’s depiction of repairing battle damage on U.S.S. Nahant, this time after a subsequent “set-to” with Confederate gunners at Fort Wagner on Morris Island.

Stedman’s depiction of repairing battle damage on U.S.S. Nahant, this time after a subsequent “set-to” with Confederate gunners at Fort Wagner on Morris Island.

![]()

Du Pont had been reluctant to stage this attack with naval forces alone; he had urged a coordinated attack, using large numbers of land troops to help secure the batteries around the perimeter of the harbor. The events of April 7 vindicated Du Pont’s original position, as well as showing the limitations of the then-still-new armored ships in attacking heavy, well-trained shore batteries. After Du Pont’s failed attack, the Union strategy shifted to one that prioritized taking the forts on the outer periphery of Charleston Harbor, gradually working toward Sumter itself. If you’ve seen the great Civil War movie Glory, you have some familiarity with that part of the war.

Finally, if you haven’t seen his posts lately, my colleague Craig Swain has been doin’ the knowledge on the development of the Confederate defenses at Charleston over at his blog, To the Sound of the Guns. It’s fantastic stuff, in all its primary-source, granular detail. Great work, Craig — you’re showing how it’s done.

___________

[1] S. F. Du Pont to Gideon Welles, “Attack by Federal ironclads upon the defenses of Charleston, S. C., April 7, 1863,” April 8, 1863. ORN, vol 14, 3.

[2] Alvah F. Hunter, A Year on a Monitor and the Destruction of Fort Sumter, Craig L. Symonds, ed. (Columbia: University of South Carolina, 1987).

[3] “Dr. Stedman” was Assistant Surgeon Charles Ellery Stedman, ship’s surgeon aboard Nahant, whose sketches illustrate this post. Charles Ellery Stedman, The Civil War Sketchbook of Charles Ellery Stedman, Surgeon, United States Navy. Jim Dan Hill, ed. (San Rafael, California: Presidio Press, 1976).

[4] Sofield’s paralysis may have been temporary; Assistant Surgeon Stedman’s after-action casualty report does not mention the paralysis, and says that Sofield “is doing well.” Pilot Sofield was still on active duty with Nahant at the end of 1863. C. Ellery Stedman, “Report of casualties on the U. S. S. Nahant,” April 7, 1863. ORN, vol 14, 5; John J. Cornwell, “Report of Lieutenant-Commander Cornwell, U. S. Navy, regarding drifting timber from the harbor obstructions,” December 29, 1863. ORN, vol 15, 210-211.

How Crowded Was Monitor‘s Turret?

Very.

Samuel Dana Greene’s account of the action with C.S.S. Virginia gives the following description:

![]()

![]()

It’s not clear to me whether the two gun captains, Stocking and Loughran, were being counted by Greene as part of the eight men assigned to their respective guns, so the total number in the turret during the action was either nineteen or twenty-one. To get a visual sense of what that looked like, I dropped nineteen figures into a model of Monitor‘s turret. This is the result:

![]()

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8264/8612835528_d4dd68fb14_b.jpg)

![]()

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8544/8611730013_b6a0e89361_b.jpg)

![]()

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8397/8611730149_e7229435a7_b.jpg)

![]()

This model doesn’t include any of the other necessary gear that would have been inside the turret, and there was additional plating on the interior surface of the turret (over the joints in the primary plating) that’s not reflected in the model. (Haven’t got to it yet.) So in reality, it was likely more cramped than shown in the model. I haven’t made any particular attempt to put crewmen in exact gun drill positions, either. Also note that the heavy, iron pendula that closed the gunports could not be opened simultaneously — there was too little space between the ports for both to swing clear toward the centerline at the same time. In practice, you would not see both guns run out at the same time.

Nonetheless, a very crowded and chaotic place.

Previous, incomplete renders of this structure are on Flickr, although those show the two hatches on the top of the turret incorrectly — the slid backwards, not inboard as specified on Eriocsson’s original plan.

________

Aye Candy: The Confederate Ironclad That Almost Was

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8524/8587301585_4855a4e2ec_b.jpg)

This model of the Confederate casemate ironclad Wilmington is based on reconstruction plans drawn in the 1960s by W. E. Geoghagen, a maritime specialist at the Smithsonian Institution. Geoghagen’s drawings, in turn, are based on surviving plans prepared by the Confederate Navy’s Chief Constructor, John L. Porter (1813-1893). Full-size images are available on Flickr.

Wilmington was the last of three ironclads built at her namesake city during the Civil War. Neither of the first two had accomplished much during its service. The first, North Carolina, was structurally unsound and, like many of her type, was woefully underpowered. North Carolina was used in the brackish Cape Fear River as a floating battery until she sank at her moorings in September 1864, her bottom eaten through by teredo. The second ironclad, Raleigh, had been completed in the spring of 1864 and sortied to attack the Union blockading fleet off Fort Fisher. Raleigh managed to drive off several blockaders but upon her return upriver grounded on a sandbar and broke her keel, effectively making her a total loss.

Construction on the new ironclad began soon after Raleigh’s loss, in the late spring of 1864. In designing the vessel, Porter sought to remedy two serious flaws exposed by Raleigh’s brief sortie against the Union fleet: first, that she lacked sufficient speed to close the range and force a fight, and second, that she drew too much water to safely operate in the Cape Fear estuary.

Porter’s design is almost unique among Confederate ironclads, with a long length-to-beam ration of more than 6.5-to-1, perhaps in imitation of the long, fast blockade runners that operated between Wilmington, Bermuda and Nassau. The new ship, dubbed by locals as the future C.S.S. Wilmington, was unusual above deck, too. While almost all Confederate ironclads built or planned for construction in the Confederacy during the war followed the pattern set in 1862 by the famous C.S.S. Virginia (ex-U.S.S. Merrimack), by using a single, large armored casemate to house the ship’s battery, the vessel being built at Wilmington would have two small, low, casemates, each with a single, heavy gun working on a pivot on the inside. Each miniature casemate was fitted with seven ports, 45 degrees apart, giving the guns a wide (if narrowly segmented) field of fire. While the Confederacy lacked the resources to construct a revolving turret like those fitted on the Union Navy’s monitors, Porter’s design was a serious attempt to replicate the monitors’ greatest tactical advantages: all-around fire by a few, very heavy guns, and presenting the enemy’s gunners with a very small target. She is somewhat unusual for Confederate ironclads in that she was not built to be fitted with a ram.

Unfortunately, Wilmington never saw action, and was never formally commissioned. (Nor was the vessel ever officially named Wilmington; that’s what the locals called her.) She was still on the stocks, nearing completion, when the city of Wilmington was evacuated. This vessel, representing perhaps the most advanced design of ironclad built in the Confederacy during the war, was put to the torch to keep her from falling into the hands of Union troops.

Because Wilmington was never completed, we cannot know exactly how she would have appeared in service. Bob Holcombe, in his masters thesis “The Evolution of Confederate Ironclad Design” (East Carolina University 1993), notes that 150 tons of one-inch plate taken from the decrepit old North Carolina might have been intended for Wilmington’s open deck. In recreating the ship, I’ve left the deck unarmored, but I did put plating over the timbered knuckle that extends outboard on either side of the ship. This model represents a “what if” depiction of the ship as she might have looked if she’d been completed and fully commissioned, sometime in the summer of 1865. I don’t think this ship (or several of them) would’ve changed the overall equation at Wilmington and Fort Fisher, but it’s intriguing to imagine how she would have performed in action. With the right engines (probably a practical impossibility in that time and place) she might have been a real menace to the blockaders as a hit-and-run raider.

Special thanks to Kazimierz Zygadlo for his assistance in compiling material on this remarkable warship-that-almost-was.

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8527/8587301749_8f582fa25a_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8531/8588402400_5988740d2c_b.jpg) Alongside the Union river monitor U.S.S. Onondaga, for comparison.

Alongside the Union river monitor U.S.S. Onondaga, for comparison.

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8227/8587302463_82a66cae63_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8105/8587302829_850ca88059_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8505/8588403410_51cb1d9769_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8531/8588403814_02fd6edeef_b.jpg)

________________

![]()

Aye Candy: C.S.S. Manassas

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8236/8565080381_49db1dc5fb_b.jpg)

Everybody knows about the famous Confederate ironclad Virginia, even if they insist on calling the vessel by its previous name, Merrimack. But there was an earlier Confederate ironclad, that went into action in the defense of New Orleans in the fall of 1861, almost five months before Virginia steamed out of Norfolk to attack the Union fleet anchored in Hampton Roads.

C.S.S. Manassas was originally conceived as a privateer, a privately-owned vessel that, holding a commission from the national government, would be formally authorized to attack (and hopefully capture) enemy shipping. Like Virginia, Manassas was built up from the hull of an existing vessel, in this case the twin-screw steamer Enoch Train. Soon after her completion in the fall of 1861, Manassas was taken over by local military authorities for use in the defense of New Orleans and the mouth of the Mississippi. In October 1861, Manassas participated in a surprise attack on the Federal fleet at the Head of the Passes. The ironclad was seriously damaged in that fight, losing her iron ram, chimneys and having one of her engines knocked off its mount. Under the command of A. F. Warley, however, Manasssas managed to withdraw successfully. The vessel was soon thereafter directly purchased by the Confederate government, and formally commissioned as a C.S. warship.

Manassas went into action again in April 1862, when the Union Admiral Farragut ran his fleet past Forts Jackson and St. Philip. Manassas was in the thick of the action, successfully striking both U.S.S. Mississippi and U.S.S. Brooklyn. A the Union fleet continued upstream, Manassas followed, until Mississippi came about and charged the ironclad. Lt. Warley avoided a collision, but grounded his ironclad on the bank in the process, where she was pounded by Mississippi‘s broadside. Manassas eventually slipped off the bank and drifted downstream, on fire, until the flames reached her magazine. The explosion completely wrecked the vessel.

____________

There are many modern illustrations and models depicting C.S.S. Manassas, and they vary considerably. Many appear to be based on a 1904 drawing by R. G. Skerrett (above), that was used in the ORN. Although Skerrett was a skilled artist who brought much of the Civil War at sea alive with his artwork, he’s most reliable when working directly from photographs or other contemporary sources. In the case of ships for which he had no detailed contemporary image sources to work from (e.g., U.S.S. Westfield), he’s less reliable. In the case of Manasssas, Skerrett’s drawing seems to make the vessel too small overall, with a tiny pop-gun mounted in her bow. Sources conflict on exactly what type of gun Manassas carried — and she may well have been fitted with different pieces at different times in her short career — but generally they agree that the piece was at minimum a 32-pounder, not an insignificant piece, especially at short range.

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/manassas11jp.jpg?w=614&h=382)

Several contemporary sources suggest, for example, that the ironclad had two chimneys, arranged side-by-side like contemporary river steamers. South Carolina digital artist Dan Dowdey, for example, used this arrangement in his recreation of Manassas (above). I like Dowdey’s work generally, and particularly his envisioning of Manassas, with the additional nautical bits (e.g., actual bitts) that aren’t mentioned in most accounts, but are necessary to make the real vessel functional.

A colleague recently shared with me reconstruction drawings of C.S.S. Manassas prepared by W. E. Geoghagen in the mid-1960s. Geoghagen was a maritime specialist with the Smithsonian Institution, working with Howard Chapelle, the dean of historic American naval architecture. Geoghagen was also working in that period with Ed Bearss and the National Park Service on the U.S.S. Cairo recovery and reconstruction. I don’t know what sources Geoghagen used for reconstructing the upperworks of the C.S.S. Manassas, but the lower hull of the vessel he drew does conform to the known dimensions of Enoch Train, 128 feet between perpendiculars, and 26 feet in beam. Geoghagen’s drawing depicts a single, thick chimney very similar to Skerrett’s, but with a pronounced rake; I’ve chosen to go with two chimneys, with minor alterations of the topside openings necessary to accommodate them.

But enough prattle. Here’s the pics. Full-size versions available on Flickr:

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8378/8565079291_36619d97b7_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8248/8566176320_38d0c23cdf_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8107/8565079597_8efaf3f93f_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8097/8565079851_462de62281_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8532/8565080057_2d53f5c428_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8390/8566177396_0744134797_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8100/8565080821_77a2fea9dc_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8532/8565081047_a3f90ef45c_b.jpg)

![[IMG]](https://i0.wp.com/farm9.staticflickr.com/8371/8565081307_474a01b975_b.jpg)

_________

Aye Candy: David-Class Torpedo Boat

Test renders of a new work-in-progress, a Confederate David-class torpedo boat like those used at Charleston, 1863-65. (The rig that suspended the torpedo spar on the bow, in particular, is missing from this incarnation.) The model incorporates features from a variety of sources, so is intended to show the general appearance of the type, as opposed to any specific, individual craft. At some point I will provide an interior for it, but as only rudimentary diagrams of the boats’ internal layout exist, the interior of the model will be even more speculative than the exterior.

![]()

![]()

And finally, one of the torpedo boat alongside the submersible H. L. Hunley. The Davids were often used to tow Hunley in and out of the harbor, to save the strength of the hand-powered submarine’s crew:

![]()

Full-size images can be seen on Flickr.

______________

Artifact Thursday: Pressure Gauge from U.S.S. Kearsarge

A fellow blogger passed along these images of a steam gauge found in a local antique shop. It was one of three purchased in a lot at an estate auction. After completing his purchase, the buyer found a note affixed to the bottom of this one, attesting to its provenance as being from the ship that sank C.S.S. Alabama off Cherbourg in 1864 — the seller either hadn’t looked, or didn’t understand its significance.

![]()

![]()

And here’s a similar gauge from the same lot — but apparently not from Kearsarge — to give a better idea of its original appearance:

![]()

![]()

I don’t know the current owner, or the asking price; I just thought it’s a remarkable and serendipitous discovery. Also unknown is whether this piece was an element of the ship’s engineering plant during the Civil War, or was added during a later refit. Kearsarge went through the postwar decommissioning/recommissioning cycle three different times before she she was finally wrecked on a reef in the Caribbean in 1894. On each of those occasions, the engineering plant likely went through an overhaul that would include replacement or refurbishing of various elements, and a gauge like this would have been generic, not custom-fitted for any particular vessel or powerplant. It’s very similar to, though probably an earlier model, the examples in this 1896 catalog of its maker, the American Steam Gauge Co. of Boston. I still have to dig into the details of Kearsarge‘s powerplant(s) to get a clearer picture there.

Anyway, cool stuff, and a big thanks to my colleague who passed it along!

____________

Aye Candy: H. L. Hunley

Update: Apologies for the double-posting on this. After the first versions of these images went online over the weekend, Michael contacted me and pointed out that there was a more updated version of his plans of the boat than the one I’d used. These images, then, are corrected to reflect his most recent edition of the drawings. Most of the changes are small, but the boat has lost that beautiful-but-functionally-inexplicable curve in the profile of her stem (right, in an earlier model); that was apparently caused by exposure to the current and environment after the boat’s loss in 1864.

Update: Apologies for the double-posting on this. After the first versions of these images went online over the weekend, Michael contacted me and pointed out that there was a more updated version of his plans of the boat than the one I’d used. These images, then, are corrected to reflect his most recent edition of the drawings. Most of the changes are small, but the boat has lost that beautiful-but-functionally-inexplicable curve in the profile of her stem (right, in an earlier model); that was apparently caused by exposure to the current and environment after the boat’s loss in 1864.

____________

![]()

Digital model of the Confederate submersible H. L. Hunley, as she may have appeared in mid-February 1864, about the time of her successful attack on U.S.S. Housatonic off Charleston, South Carolina. The spar torpedo is based on recent findings announced in January 2013 by archaeologists at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, which is conserving the boat and its contents. Model based on plans by Michael Crisafulli. Full-sized images available on Flickr. All rights reserved.

More after the jump:

![]()

The Fate of the Confederate Submersible H. L. Hunley

Big news came out Monday in the investigation of the remains of the Confederate submersible Hunley, arguably the most important scientific finding of the project to date. Archaeologists revealed that the cleaned an conserved remains of the iron spar that carried the boat’s 135 lb. (61kg) torpedo still had attached remnants of the explosive device’s copper casing, peeled back by the force of the explosion (above). This is a tremendously important finding, because it shows that the little “fish boat” was close, very close, the blast that sank her opponent, U.S.S. Housatonic. How close?

Here’s why. Hunley was originally intended to tow a floating mine (then called a “torpedo”) behind her, and run under the target ship. If all went according to plan, the mine would be pulled into the side of the enemy vessel and detonate — on the opposite side from where Hunley was.

Unfortunately, this worked better in theory than in practice. In testing, they found that the towing line was prone to getting fouled in the boat’s propeller and rudder mechanism. Hunley’s ability to dive and run completely submerged — in order to pass underneath the target vessel — was problematic, as well, as shown by two prior, fatal sinking of the boat. (Not for nothing was it known as the “peripatetic coffin.”) Clearly, they had to find a method to deliver the mine to its target that gave them precise control, which in turn meant planting the mine against the target ahead of the boat, not towing it along behind.

![]()

Hunley Project Chief Archaeologist Maria Jacobsen. Charleston Post & Courier.

Hunley Project Chief Archaeologist Maria Jacobsen. Charleston Post & Courier.

![]()

For years, it’s been generally accepted that Hunley‘s mine was detachable and fitted with a spike or barb, that would be rammed into the target’s hull. Once that was fixed in place, the submersible would back off for a safe distance, and detonate the mine using a lanyard, in the same way that period artillery pieces were fired. Up to today, this was the accepted scenario of how the attack was supposed to have been carried out. The physical evidence revealed in Charleston on Monday, however, suggests that experience gained in another attack on a blockading warship caused a critical change in those plans:

![]()

As a result, the scientists now believe, George Dixon and his crew set out on the evening of February 17, 1864, with the intention of placing the mine not in the enemy ship’s side, but under the hull, anticipating that most of the blast would be directed upward, ripping apart that part of the vessel. This interpretation in supported by witnesses aboard Housatonic, who first sighted Hunley a couple of hundred yards off their port bow, then watched as the submersible passed across their bow, then came around to strike their ship well aft on the starboard side, where the contour of the hull sweeps in and up toward the stern.

That sort of attack, if were planned that way as the researchers now believe, almost certainly doomed Hunley and her crew. Nonetheless, neither the project’s chief archaeologist, Maria Jacobsen, nor South Carolina Lieutenant Governor Glenn McConnell, who’s led the fund-raising for the project since its inception, believe Dixon and his crew expected theirs to be a suicide mission. “They were pressed for time, they were pressed for resources, but nothing indicates this was a suicide mission,” Jacobsen said. “They just had to get the job done.”

![]()

Detail of a painting, “Charleston Bay and City,” by Conrad Wise Chapman, showing a Confederate ironclad with a spar torpedo (show in raised position) very similar to that used aboard Hunley. Museum of the Confederacy.

Detail of a painting, “Charleston Bay and City,” by Conrad Wise Chapman, showing a Confederate ironclad with a spar torpedo (show in raised position) very similar to that used aboard Hunley. Museum of the Confederacy.

![]()

Lots of questions about what happened that night remain, including ones underscored by Monday’s announcement about the spar torpedo. Though the crew probably had little idea of how the concussion from the detonation of the mine would have carried underwater, the force must have been tremendous. While the hull of the boat itself remains covered for now with cement-like concretions of sand and shell, when these are removed beginning next year, Jacobsen and her team will be looking closely for effects of the blast, in the form of popped rivets and opened seams between the iron plates. It would not take many of these to sink a boat like Hunley, that had precious little buoyancy to begin with, even under ideal conditions. If her crew were incapacitated as well, Hunley could easily have drifted, slowly filling with water, until she settled on the bottom some distance away.

We likely never will know all the details of what happened that night in February 1864, but the work of Jacobsen and her team at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, where Hunley is being studied and preserved, are getting us closer and giving us a better understanding of those events.

In the meantime, I’ve updated the spar on my old digital model of H. L. Hunley. There’s a spool on the starboard side of the boat, next to the forward hatch. Until it was assumed that this was for unspooling the lanyard used to detonate the mine; now I think it may have led through a block on the upper boom, to raise and lower the spar. That’s how I’ve depicted it here:

Finally, a few good Hunley links for those interested in learning more:

Michael Crisafulli’s Hunley reconstruction:http://www.vernianera.com/Hunley/ Michael likely knows more about the construction and operation of the Hunley than anyone not directly affiliated with the project. Great stuff for the technically-minded. (Michael also can give you a guided tour of Jules Verne’s Nautilus, as well.) NPS Housatonic Site Assessment

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/maritime/housatonic.pdf NPS Hunley Site Assessment:

http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/maritime/hunley.pdf

___________

The Short, Eventful Life of the U.S. Transport Che-Kiang

In my recent post on Private Hobbs’ passage from Brooklyn to Ship Island, Mississippi aboard the steamer Saxon, I included an image of another transport on that same expedition, Che-Kiang, which is reported to have collided (above) with a Confederate schooner off the Florida Reef, resulting in the latter vessel’s immediate demise. Che-Kiang was carrying at that time six companies of the 28th Connecticut Infantry, and parts of the 23rd and 25th Connecticut Infantry as well. All reached Ship Island, Mississippi safely, although some were perhaps a little green around the gills from the very rough weather encountered during their passage.

While poking around the interwebs for more information on this ship, though, I came across this article from the June 20, 1863 Straits Times, published in Singapore. Che-Kiang‘s rough passage to the Gulf of Mexico was just the start of her adventures.

![]()

![]()

In his History of American Steam Navigation (1903) author John Harrison Morrison explains that Che-Kiang was one of several big steamers built in and around New York, to run in Chinese waters. Most were patterned after boats running on Long Island Sound, with the addition of a sailing rig. Although Che-Kiang herself apparently did not, Morrison notes that several of these ships that were built during the war, following the same route as Che-Kiang to the Far East, stopped first at Halifax, Nova Scotia, where they took out British registry in case they were intercepted on the high seas by a Confederate raider. [2] It was not an imaginary threat; the most famous Confederate raider, Raphael Semmes’ Alabama, did in fact follow a similar route and ventured as far east as Singapore in late 1863.

![]()

Track chart showing the known travels of the American steamship Che-Kiang, 1862-64. Original map via National Geographic.

Track chart showing the known travels of the American steamship Che-Kiang, 1862-64. Original map via National Geographic.

![]()

Che-Kiang even played a sad, tiny footnote role in the aftermath of the Battle of Galveston. In late February 1863, U.S. Admiral David Farragut reported to the Navy Department the desertion of Acting Master Leonard D. Smalley, at that time assigned to the gunboat Estrella. Smalley had been one of the officers aboard U.S.S. Westfield when that ship was blown up by her captain, William Renshaw, at the end of the battle on New Years Day 1863. Renshaw and several of his men had been killed in the blast, which Smalley almost certainly witnessed from a short distance. Immediately after, Smalley was called on to serve as pilot to guide the transport Saxon, followed by the rest of the Union squadron, safely out of Galveston harbor. Smalley, it seems, may have been suffering the post-traumatic effects of this incident, for Farragut writes that

![]()

![]()

Acting Master Smalley was dismissed from the service soon thereafter.

In her first few months of service, Che-Kiang had seen and done some remarkable things, but her eventful life would not be a long one. She caught fire and burned at Hankou (now Wuhan), about 670 statute miles up the Yangtze River from Shanghai, on August 7, 1864. There were no reported fatalities in the disaster. [4]

______________

[1] “The Steamer Che Kiang,” The Straits Times, June 20, 1863, 1.

[2] John Harrison Morrison, History of American Steam Navigation (New York: W. F. Sametz & Co, 1903), 511.

[3] D. G. Farragut to Gideon Welles, February 26, 1863. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I, Vol. 19, 634.

[4] C. Bradford Mitchell, ed. Merchant Steam Vessels of the United States, 1790–1868 (The Lytle-Holdcamper List), (Staten Island, New York: Steamship Historical Society of America, 1975), 249.

Wreck of the Steamship Celt, 1865

This Library of Congress image is one of the most famous of Civil War blockade runners, but it’s almost never identified — only the location is given, on the shore of Sullivan’s Island, near Charleston. I believe this is the wreck of the sidewheel steamer Celt, ashore just off Fort Moultrie. Although the specific location of this image is not recorded in the LoC catalog information, during the war period there was only one point on Sullivan’s Island with a stone jetty or breakwater extending into the water like the one shown in the foreground of the image. That was Bowman’s Jetty, which entered the water directly in front of Moultrie. Jetties like that are commonly used on barrier islands like Sullivan’s to reduce erosion from currents running parallel to the shore.

This sketch map from the NOAA archives, prepared at the end of the war in 1865 — roughly the same time the photograph was made — shows the wreck site of Celt close up on the beach, with the wrecks of two screw steamers, Minho (lost October 2, 1862) and Isaac Smith (a.k.a. Stono, destroyed June 5, 1863), further out along the jetty. As Isaac Smith/Stono was burned, it seems likely that the wrecked ship in the background is Minho.

![]()

![[IMG]](https://deadconfederates.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/celtmap.jpg?w=720)

![]()

Celt was built at Charleston during the war, which helps explain the relatively simple machinery construction apparent in the image. Launched in 1863, the 160-foot steamship she was used by the C.S. Quartermaster in and around the harbor until February 1865, when she was loaded with cotton and attempted to run out through the blockade. Celt was wrecked near Moultrie on February 14, 1865. Although the steamer was grounded in shallow water, yards from the beach, six or seven of her crew took to a boat and rowed out to a Federal warship instead. Her cargo, or most of it, also ended up in the Federals’ hands (ORN):

![]()

![]()

The Federals recovered at least 190 bales of cotton from the wreck, but reported in early March that Celt‘s hull “lies stranded on the beach at Sullivan’s Island, back broken, and full of water, and decks ripped up. The machinery is in an irreparable condition; some few pieces might be removed and be of service. Boilers are mostly below water, but judging from the condition of those parts visible, we are of the opinion they are not worth the expense of removing.” This is a good description of her state in the photograph, as well.

![]()

![]()

There’s some interesting detail in the photograph that hint at the vessel’s origins as a local craft built under the exigencies of wartime. Celt has two engines (left, above) that, while partially submerged, appear to be arranged as in a Western Rivers boat, and the valving shown looks to be almost identical. Such engines were reliable and simple but not overly efficient. They also operated under very high pressure compared to most seagoing ships, and so may have required a more robust set of boilers. Similarly, the paddlewheels are of very simple construction, with wooden arms and fixed floats (paddle blades). As with the engines, this is a very basic design, easy to build and maintain, but not efficient and somewhat coarse by shipbuilding standards of the time.

![]()

Modern aerial view of Fort Moultrie (via Google Earth), with the remains of Bowman’s Jetty still visible at upper right. The beach has extended further out from its position in 1865, placing (it is believed) the wreck of Celt under the sand.

![]()

The wreck site of Celt, as well as Isaac Smith/Stono and Minho, was the subjects of an extensive archaeological survey in 2012 by a team from the University of South Carolina. Although what remains of Celt is now believed to be under sand, some distance back from the shore, the wreck was not located at that time.

The original images was part of a stereo pair. Here is is in red/cyan, and as an animated GIF:

_____________

3 comments