“Possessed of an irascible temper, and naturally disputatious.”

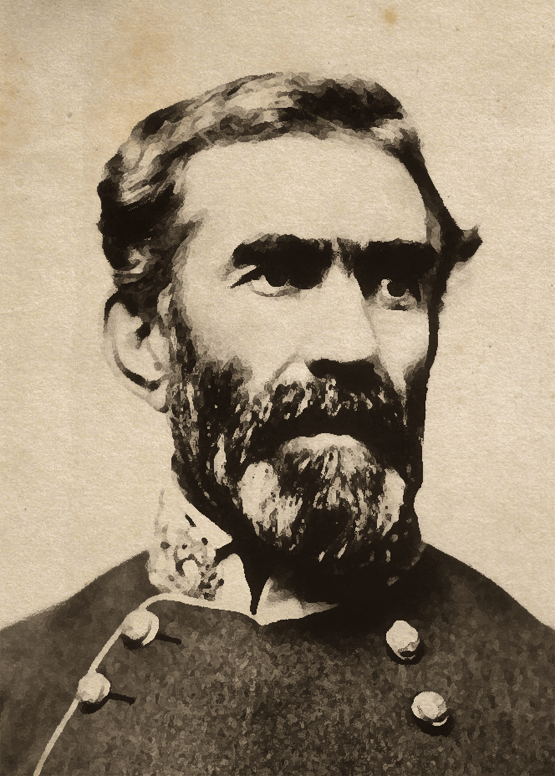

Over at KNOXVILLE 1863, the novel, Dick Stanley has a couple of posts up on Confederate General Braxton Bragg. They paint a picture of a man who was decidedly not popular, either with his men or with his fellow senior officers. He was a prickly man, very much caught up in protocol and form. In his own memoir, Ulysses S. Grant echoes some of their impressions of the man — honest, industrious, and decidedly formal with colleagues. Grant goes on to repeat an anecdote about Bragg from the prewar Army which, accurate or not, vividly captures Bragg’s obsession with procedure:

Bragg was a remarkably intelligent and well-informed man, professionally and otherwise. He was also thoroughly upright. But he was possessed of an irascible temper, and was naturally disputatious. A man of the highest moral character and the most correct habits, yet in the old army he was in frequent trouble. As a subordinate he was always on the lookout to catch his commanding officer infringing his prerogatives; as a post commander he was equally vigilant to detect the slightest neglect, even of the most trivial order.

I have heard in the old army an anecdote very characteristic of Bragg. On one occasion, when stationed at a post of several companies commanded by a field officer, he was himself commanding one of the companies and at the same time acting as post quartermaster and commissary. He was first lieutenant at the time, but his captain was detached on other duty. As commander of the company he made a requisition upon the quartermaster–himself–for something he wanted.

As quartermaster he declined to fill the requisition, and endorsed on the back of it his reasons for so doing. As company commander he responded to this, urging that his requisition called for nothing but what he was entitled to, and that it was the duty of the quartermaster to fill it. As quartermaster he still persisted that he was right. In this condition of affairs Bragg referred the whole matter to the commanding officer of the post. The latter, when he saw the nature of the matter referred, exclaimed: “My God, Mr. Bragg, you have quarreled with every officer in the army, and now you are quarreling with yourself!”

_____________________________

“Sympathies and antipathies are disabilities in an historian.”

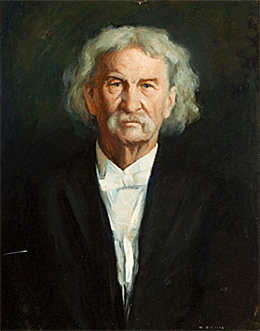

Archibald Gracie IV (1859-1912, left) is today remembered primarily as a survivor of the Titanic disaster, who wrote one of the better first-person accounts of the sinking. Gracie, who had attended (but not graduated from) West Point, was an energetic amateur historian, and was particularly obsessed with the Battle of Chickamauga, in which his father, Archibald Gracie III (1832-1864), had served as a Confederate brigade commander. The younger Gracie spent years researching the battle, work which culminated in his December 1911 publication, The Truth About Chickamauga. Gracie took an extended trip to Europe after completing the volume, booking return passage on the soon-to-be-infamous White Star liner. He apparently hadn’t quite gotten Chickamauga out of his system for, as the late Walter Lord wrote in The Night Lives On, “he cornered Isidor Straus, on whom he had foisted a copy of The Truth About Chickamauga. The book strikes one reader as 462 pages of labored minutiae, but Mr. Straus was famous for his tact; he assured the colonel that he had read it with ‘intense interest.'”

Archibald Gracie IV (1859-1912, left) is today remembered primarily as a survivor of the Titanic disaster, who wrote one of the better first-person accounts of the sinking. Gracie, who had attended (but not graduated from) West Point, was an energetic amateur historian, and was particularly obsessed with the Battle of Chickamauga, in which his father, Archibald Gracie III (1832-1864), had served as a Confederate brigade commander. The younger Gracie spent years researching the battle, work which culminated in his December 1911 publication, The Truth About Chickamauga. Gracie took an extended trip to Europe after completing the volume, booking return passage on the soon-to-be-infamous White Star liner. He apparently hadn’t quite gotten Chickamauga out of his system for, as the late Walter Lord wrote in The Night Lives On, “he cornered Isidor Straus, on whom he had foisted a copy of The Truth About Chickamauga. The book strikes one reader as 462 pages of labored minutiae, but Mr. Straus was famous for his tact; he assured the colonel that he had read it with ‘intense interest.'”

Also not a fan of The Truth About Chickamauga: Ambrose Bierce. The famous writer had served at Chickamauga on the staff of Brigadier General William Babcock Hazen (1830-1887), personally witnessed several key events in the battle, had published several pieces on the action, and apparently gave Gracie at least one face-to-face interview. But Bierce found Gracie’s efforts at telling the truth about Chickamauga to be badly and willfully biased. Here is the opening paragraph of a letter Bierce wrote to Gracie in March 1911, several months before the latter’s book went to press:

March 9, 1911

From the trouble that you took to consult me regarding certain phases of the battle of Chickamauga I infer that you are really desirous of the truth, and that your book is not to belong to that unhappily too large class of books written by “bad losers” for disparagement of antagonists. Sympathies and antipathies are disabilities in an historian that are hard to overcome. That you believe yourself devoid of this disability I do not doubt; yet your strange views of Thomas, Granger and Brannan, and some of the events in which they figured, are (to me) so obviously erroneous that I find myself unable to account for them on the hypothesis of an entirely open mind. All defeated peoples are “bad losers” – history supplies no examples to the contrary, though there are always individual exceptions. (General D. H. Hill is an example of the “good loser,” and, with reference to the battle of Chickamauga, the good winner. I assume your familiarity with his account of that action, and his fine tribute of admiration to some of the men whom he fought — Thomas and others.) The historians who have found, and will indubitably continue to find, general acceptance are those who have most generously affirmed the good faith and valor of their enemies. All this, however, you have of course considered. But consider it again.

Ouch.

______________________

Letter from Phantoms of a Blood-Stained Period: The Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce (Russell Duncan and David J. Klooster, eds.)

Spoons Butler, Yellow Jack and the Crescent City

Uncle Abe: “Hell! Ben, is that you? Glad to see you!’

Butler: “Yes, Uncle Abe. Got through with that New Orleans Job. Cleaned them out and scrubbed them up! Any more scrubbing to give out?

_____________

Ron Coddington, blogger and author of the Faces of the Civil War series, has a new post up on Union General Benjamin Franklin Butler. Coddington rightly notes that the general “is not remembered especially well by history.” That’s certainly true. Between his ineptitude as a field commander and the vilification of him resulting from the sharp hand he used in the occupation of New Orleans, Butler gets pretty short shrift in most popular accounts. But as Ron points out, Butler — a former Democrat who at that party’s national convention in 1860 supported Jefferson Davis for president of the United States — was transformed by his war experience into a radical Republican and an ardent champion of civil rights for African Americans. He drafted the Ku Klux Klan Act, signed into law by President Grant in 1871, and (with Charles Sumner) wrote the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The latter legislation was subsequently struck down by the Supreme Court, and many of its key provisions were never enacted until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — nearly eighty years after they were first set out. As Ron observes, “Butler was a man ahead of his time.”

Butler is often cited as the most infamous example of the Union’s “political” generals, men with little or no military experience who were appointed to senior commands based on their political influence in civilian life. His reputation, at least in the South, is defined by his tenure in New Orleans, where he attained the sobriquet “Beast” Butler for his intolerance of any show of disrespect for his occupying soldiers, and his vigorous enforcement of the rules of occupation. (He infamously hanged a Confederate sympathizer for tearing down the Federal flag from the U.S. Mint.) What’s less known, unfortunately, is the remarkable success Butler’s administration of the city had in reducing its infamously-high toll from that scourge of the South, yellow fever. As Andrew McIlwaine Bell explains in Mosquito Soldiers: Malaria, Yellow Fever and the Course of the American Civil War, New Orleans had a long and horrific history with the disease in the decades before the war, particularly in the 1850s, resulting in the deaths of over eighteen thousand people. The vomito negro was particularly hard on immigrants and visitors to the cities from Northern states; the illness was often referred to as the “strangers’ disease.” Butler was well aware of New Orleans’ reputation as a sickly city, and immediately set out to do something about it.

After consulting with his medical staff and a few local doctors (some of whom were openly hostile), Butler decided that yellow fever was an imported malady that required local unsanitary conditions to survive. As a result, he chose to implement simultaneously the two strategies best known at the time for preventing the spread of the disease-a strict quarantine and fastidious sanitation measures. A quarantine station was set up seventy miles below the city and its officers given firm orders to detain any potentially infected vessels for forty days. In addition, a local physician was appointed to inspect incoming ships at the station and was threatened with execution if any vessels known to be carrying yellow fever were allowed to proceed upriver. These new rules caused a minor diplomatic row with the Spanish; who believed that their ships arriving from Cuba (where yellow fever was endemic) were being unfairly targeted for lengthy detentions. Butler assured Senor Juan Callejon, Her Catholic Majesty’s consul in New Orleans, that he was not imposing “any different quarantine upon Spanish vessels sailing from Havana.” To the relief of the State Department, Spain eventually dropped the matter but not before firing off a few strongly worded communiques.

In town Butler put an army of laborers to work round the clock flushing gutters, sweeping debris, and inspecting sites thought to be unclean such as stables, “butcheries;’ and New Orleans’s many “haunts of vice and debauchery.” Steam-powered pumps siphoned stagnant water from basins and canals into nearby bayous. The northern press picked up the story and ran articles praising Butler’s methods. “He will probably demonstrate before the year is out that yellow fever, which has been the scourge of New Orleans, has been merely the fruit of native dirt, and that a little Northern cleanliness is an effectual guarantee against it,” predicted the editors at Harper’s Weekly. The magazine published a cartoon five months later which featured the general holding a soap bucket and scrub brushes in front of an approving Abraham Lincoln.

In addition to cleaning up the place, Butler also imposed a strict quarantine. How effective were Butler’s efforts? According to Bell, during the fever season of 1862 — the hottest months of late summer and early fall, ending with the first cold front — the number of fatalities to yellow fever in the Crescent City were two.

Such a small number is hard to credit, but it appears to be true. Furthermore, deaths remained astonishingly low during the next three years of Federal military occupation. A total of eleven New Orleanians died of yellow fever between 1862 and 1865. The year following the war, when the city was reopened to trade and immigration and local control was returned to civilian authorities under Reconstruction, 185 died. The following year, 3,107. New Orleans quickly slipped back into its old, antebellum pattern of mild years punctuated by terrible epidemics; over four thousand died in 1878, and the following year the disease famously claimed the life of former General John Bell Hood, his wife and one of his eleven children.

Such a small number is hard to credit, but it appears to be true. Furthermore, deaths remained astonishingly low during the next three years of Federal military occupation. A total of eleven New Orleanians died of yellow fever between 1862 and 1865. The year following the war, when the city was reopened to trade and immigration and local control was returned to civilian authorities under Reconstruction, 185 died. The following year, 3,107. New Orleans quickly slipped back into its old, antebellum pattern of mild years punctuated by terrible epidemics; over four thousand died in 1878, and the following year the disease famously claimed the life of former General John Bell Hood, his wife and one of his eleven children.

Today, Ben Butler is too often viewed as a curious admixture of ogre and buffoon, something of a cross between William Tecumseh Sherman and Oliver Hardy. But the reality is, as always, more complex. Whatever else one may say about his hard-handed rule in New Orleans, there’s little doubt that his efforts in both enforcing a quarantine and cleaning up the city made a tremendous difference, and saved many lives that would have a been lost otherwise even in a “mild” year.

____________________

Image: Harper’s Weekly, 1863, via Abraham Lincoln’s classroom; tomb of Sercy (newborn), Mary Love (22 months) and Edwin Given Ferguson (4 years), who died of yellow fever in New Orleans on August 30 and 31, 1878, via NOLA Graveyard Rabbit.

The Gettysburg Casino

This is a great video, and hits exactly the right chord. For what it’s worth, Matthew Broderick’s g-g-grandfather fought on Culp’s Hill with the 20th Connecticut Infantry. Not sure why this wasn’t mentioned in the video; it’s one of those small details that mean a lot when it comes to making the case for the preservation of Gettysburg.

___________

h/t Kevin Levin.

“I know of no other way for us to end the war than to retaliate”

Running through the 1865 compilation, Soldiers’ Letters from Camp, Battlefield and Prison, I was struck by this letter’s clarity and direct, matter-of-fact language.

Vidalia, La.

May 17th, 1864There has been a party of guerrillas prowling about here, stealing horses and mules from the leased plantations. A scouting party was sent out from here, in which was a company of colored cavalry, commanded by the colonel of a colored regiment. After marching some distance, they came upon the party of whom they were in pursuit. There were seventeen prisoners captured and shot by the colored soldiers. When the guerrillas were first seen, the colonel told them in a loud tone of voice to “Remember Fort Pillow.” And they did: all honor to them for it.

If the Confederacy wish to fight us on these terms, we are glad to know it, and will try and do our part in the contest. I do not admire the mode of warfare, but know of no other way for us to end the war than to retaliate.

Lieut. Anson T. Hemingway

70th U.S. Col. Regiment

I’ve seen no better example of the way one atrocity is used to justify another in wartime, fueling an endless, violent spiral of reprisal and revenge. And yet, knowing what happened at Fort Pillow, I cannot be sure I’d have tried to stop those cavalrymen. The desire for retribution is very strong, and very human.

Anson Tyler Hemingway was born in East Plymouth, Connecticut in 1844. He moved to Chicago with his family at age ten. Hemingway enlisted in Company D of the 72nd Illinois Infantry and served with that regiment at Vicksburg. Mustered out of the service, he later joined Company H, 70th USCT as 1st Lieutenant and also served as provost martial of the Freedman’s Bureau in Natchez. Hemingway was mustered out of the service in March 1866, after which he attended Wheaton College. Two of Hemingway’s brothers had died in the war. After two years at Wheaton, Hemingway took a position as general secretary of the Chicago YMCA. He later established a real estate business in Oak Park. He died in 1926 at the age of 82.

Anson Tyler Hemingway was born in East Plymouth, Connecticut in 1844. He moved to Chicago with his family at age ten. Hemingway enlisted in Company D of the 72nd Illinois Infantry and served with that regiment at Vicksburg. Mustered out of the service, he later joined Company H, 70th USCT as 1st Lieutenant and also served as provost martial of the Freedman’s Bureau in Natchez. Hemingway was mustered out of the service in March 1866, after which he attended Wheaton College. Two of Hemingway’s brothers had died in the war. After two years at Wheaton, Hemingway took a position as general secretary of the Chicago YMCA. He later established a real estate business in Oak Park. He died in 1926 at the age of 82.

Anson Hemingway’s grandson Ernest also enjoyed some success as a writer.

__________

Image: Wheaton College Archives and Special Collections

Mrs. Grant’s Donation

Rusty Williams, over at My Old Confederate Home blog, makes a great find: President Grant’s widow, Julia Dent Grant, made a $25 donation to the Confederate Soldier’s Home in Austin. Sure enough, the Galveston Daily News of March 15, 1889, confirms:

Aiding the Confederate Home

New York, March 14 — Secretary Oliver Downing of the New York Citizen’s committee, to aid the National Confederate Soldier’s home at Austin, Tex., has received a letter from General Alfred Pleasanton containing money. Another letter from Mrs. Grant incloses [sic.] a check for $25. The letter is as follows:

Oliver Downing, Secretary, Etc. — Dear Sir: General Grant’s kindly feelings toward the southern people, though they were once his enemies, is Mrs. Grant’s reasons for sending the inclosed check. She wishes you success in your efforts.

Fred D. Grant, for Mrs. Grant

Simkins Hall Update

From the Houston Chronicle:

The University of Texas’ governing board voted unanimously this morning [Thursday, July 15] to rename a dormitory and park named after former leaders of the Ku Klux Klan. . . .

The new names will be Creekside Residence Hall and Creekside Park.

The dormitory, built in 1955 on the banks of Waller Creek, was named for William Stewart Simkins, who taught at the law school from 1899 to 1929 and previously had been a leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Florida.

The park had been named for Simkins’ brother, former UT regent Judge Eldred Simkins, who also was involved with the Klan.

Good move. Some have argued that changing the name of the dorm is an attempt to cover up or deny an ugly historical fact — “history is history,” they say. That’s wrong. This move is exactly the opposite, in that it exposes a more complete view of both the Simkins brothers and the University of Texas in the first half of the 20th century. Professor Simkins contributed a great deal to the early university. That is widely recognized, and will not change. But he brought with that a shameful and hateful advocacy for racial violence and intimidation. He never repudiated that; in fact, he reveled in it. That is not something that should be honored, and you cannot honor the man without honoring the whole man. And in the Simkins brothers’ case, theirs is a deeply disturbing legacy.

200 Dozen Quails, Larded and Roasted. . . .

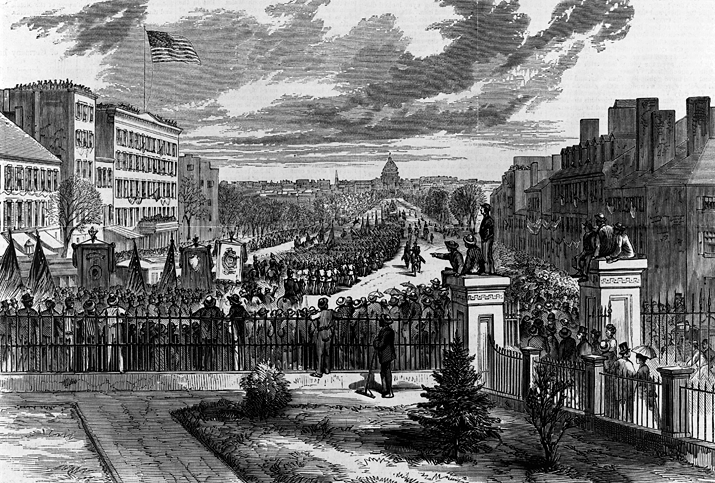

President Grant reads his Second Inaugural Address at the East Front of the Capitol, March 4, 1873. Seated, bareheaded, to Grant’s immediate left is Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, who had run against Grant the previous November. Image: Library of Congress.

In the U.S. presidential election of 1872, Ulysses S. Grant coasted to an easy victory, with 55% of the popular vote and 286 electoral votes, more than a hundred more than needed to win the White House. Washington prepared for a grand inaugural, the first for a president reelected in peacetime since Andrew Jackson. Trains to Washington was swarmed with “inauguralists,” carrying with them only enough hand luggage to accommodate a couple of nights’ stay in the city. But that first week of March 1873 proved to be bitterly, bitterly cold. The president’s speech, delivered on the East Front of the Capitol, was mercifully short at just 1,338 words.

Grant’s inaugural procession marches up Pennsylvania Avenue toward the Capitol. Image: Library of Congress.

But the preparations, months in the making, proceeded apace. The correspondent from the Titusville, Pennsylvania Herald got a sneak peek at the ballroom under construction a few days before the big event:

The ball room, with its sixty chandeliers is nearly completed; the arched ceiling being one mass of crimson and gold ornaments, on a back ground of white muslin. The bases of the arches that span the building and in support the roof, some thirty in number, are covered with a framework running up some twenty feet, and coming to a point at the top, not unlike the gable ends of the ancient buildings of Nuremberg. The woodwork m painted in imitation of columns, the colors used being light brown and yellow. On tho space at the top are painted patriotic legends, such as ”Pro Bono Publico,” “Ecce Homo,” etc. At the back of these the sides of the ball room are covered with white muslin so that the decorations stand out in bold relief.

The designs for the ends of this room are also very elegant. The one at the north end will represent an arch supported by columns, under which a [illegible] ground of red, white and blue will bear the names of Grant and [Vice President-elect Henry] Wilson. The whole finished off with the coat of arms of the United States, banners, festoons, gas-jets, transparencies, etc. The design at the opposite (south) end is not so elaborate, but still very neat. From a red Maltese cross in the center will radiate festoons of the national colors, bearing appropriate inscriptions in frames of laurel and gold. Looking down the immense hall, tbe effect produced is very beautiful.

The planned menu was no less grand. From the Waikato Times (New Zealand), 15 July 1873:

Presidential Bill of Fare — The grand “inauguration ball” in honor of President Grant, was given at Washington on the 5th inst., and if the assembled|guests consumed all the supper provided for them they must hare got almost satisfied by the close of the entertainment, and let us hope comfortable on the morning of the 6th inst. The following is the list of things, which, according to the New York Herald, of the 2nd inst., had been forwarded from that city to Washington in preparation for what it terms ” the grand blowout:” — 10,000 fried oysters; 8,000 scalloped oysters; 8,000 pickled oysters; 65 boned turkeys of 12lb each, 150 roast capons, stuffed with truffles; 15 saddles of mutton, about 10lb each; 40 pieces of spiced beef, 40lb each ; 200 dozen quails, larded and roasted; 100 game pates, 50lb each; 300 tongues, ornamented with jelly; 30 salmon, baked; Montpelier butter; 100 chickens; 400 partridges; 25 bears’ heads, stuffed and ornamented; 40 pates de foie gras, 10lb each; 2,000 head cheese sandwiches; 3,000 ham sandwiches; 3,000 beef tongue sandwiches; 1,500 bundles of celery; 30 barrels salad; 2 barrels lettuce; 350 chickens boiled for salad; 1 barrel of beets; 2,500 loaves of bread; 8,000 rolls; 21 cases Prince Albert crackers; 1,000lb butter; 300 Charlotte russes, 1½lb each; 200 moulds white jelly; 200 moulds blanc mange; 300 gallons ice cream, assorted; 200 gallons ices, assorted; 400lb mixed cakes, 150lb large cakes, ornamented; 60 large pyramids, assorted; 25 barrels Malaga grapes; 15 cases oranges; 5 barrels apples; 400lb mixed candies; 10 boxes mums; 200lb shelled almonds; 300 gallons claret punch; 300 gallons coffee; 200 gallons tea; 100 gallons chocolate; besides “oil, vinegar, lemons, and trimmings of all sorts.” The cost of this feast had not vet been estimated, but for the baking and preparing alone $10,000, and for the hire of the dishes $5,200 (with breakage and damage to be made good) had been paid. The supper would of course have been a little more bountiful, but that unfortunately the Americans are at present clothed in sackcloth, and engaged in rigidly observing the Lenten fast.

Despite such a vast and remarkable menu — and really, who wouldn’t be proud to lay out “25 bears’ heads, stuffed and ornamented” for a few thousand of your closest friends — the inaugural ball didn’t go well. Learning a lesson from his first inauguration, where the space allotted had been insufficicient for the crowds, a cavernous temporary structure was built on Judiciary Square. It was magnificently outfitted and decorated (above), but lacked one critical feature: it had no heat. On the evening of the ball, the mercury dropped to four degrees below freezing. A strong wind rippled through the huge building as guests put on their overcoats and bundled up against the chill. Hundred of canaries, brought in to sing and chirp happily, dropped to the bottom of their cages, frozen.

President Grant’s second inaugural ball, March 5, 1873. Library of Congress. The artist discretely omitted the fur coats, overcoats and hats donned by the attendees to keep out the cold. Image: Library of Congress.

Reflecting Grant’s own emphasis on civil rights, the inaugural committee had insisted that the ball be opened to all, “without distinction of race, color or previous condition.” But news reporters recorded disdainful descriptions of well-dressed African American couples, and commented on Naval Academy midshipmen dancing with “the wives of colored congressmen.” The dancing for all, to be sure, was enthusiastic; everyone took regular turns on the dance floor to keep the blood flowing in the deep winter chill. Little of the food was touched, and it soon congealed into a cold mess. Party-goers swarmed the hot coffee, tea and chocolate, which soon were exhausted. The guests, who’d purchased tickets at $20 each (about $370 today), had almost all gone home by midnight.

The Boston Daily Globe reported on March 7 that the ball had posted a net loss of $20,000.

h/t: Suzy Evans, Lincoln’s Lunch.

William Stewart Simkins, the Klan and the Law School

On Friday, University of Texas at Austin President William Powers Jr. issued a statement calling on the university’s Board of Regents to change the name of Simkins Hall, a dorm for graduate and law students. The dorm, built in the 1950s, is named for a famed UT law professor who was a Confederate officer and, as a recent publication points out, a senior leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Florida during Reconstruction and a lifelong, unabashed defender of the “Invisible Empire” throughout his later tenure at the university. The Board of Regents is likely to consider the president’s recommendation at a meeting this week.

William Stewart Simkins (1842-1929) was a well-known member of the faculty at the University of Texas, teaching there from 1899 to 1929. Although he officially attained emeritus status in 1923, he continued to lecture weekly until his death. “Colonel Simkins,” as he was sometimes called, was a memorable teacher, and something of a character. He was grumpy and irritable. He drank whiskey and once got into a famous argument with the temperance leader Carrie Nation. “Many students were scared of him,” one old alum wrote, “but I always got on well with him and did well in his class.”

William Stewart Simkins (1842-1929) was a well-known member of the faculty at the University of Texas, teaching there from 1899 to 1929. Although he officially attained emeritus status in 1923, he continued to lecture weekly until his death. “Colonel Simkins,” as he was sometimes called, was a memorable teacher, and something of a character. He was grumpy and irritable. He drank whiskey and once got into a famous argument with the temperance leader Carrie Nation. “Many students were scared of him,” one old alum wrote, “but I always got on well with him and did well in his class.”

Simkins was a South Carolinian by birth, and enrolled at the Citadel in the years just before the outbreak of the Civil War. In January 1861, it was Cadet Simkins who sounded the alarm when lookouts sighted Star of the West, a civilian steamer sent by the Buchanan administration to bring supplies to the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter. (Some contemporary accounts credit Simkins with firing the initial gun, widely recognized as the first shot of the Civil War.) Simkins was subsequently commissioned as an artillery officer in a South Carolina battery, participated in the defense of Charleston Harbor in 1863, and ended the war in 1865 as a colonel.

After the war, Simkins settled in Florida, where he and his older brother, Eldred James Simkins (1838-1903), soon helped organize that state’s Ku Klux Klan. By his own admission, William Stewart Simkins played a central role in coordinating that organization’s violence and intimidation against both white “carpetbaggers” and African Americans who challenged the prewar social or political order. Simkins not only acknowledged his role in the Klan’s violent activities, he fairly bragged about his own deeds. In an infamous speech he gave fifteen years after joining the UT faculty — and a half-century after the war — Simkins told of how he ambushed an African American state senator who had spoken out publicly against Simkins’ and his friends’ publication of a anti-Reconstructionist newspaper:

Now in the same town there was a negro [sic.] by the name of Robert Meacham who was. . . brought up as a domestic servant in a refined Southern family and absorbed much of the courteous manner of the old regime. He had been highly honored by the Republican party; in fact, had been made temporary chairman of the so-called Constitutional Convention heretofore referred to. He was at the time of which I am now speaking State Senator and Postmaster in the town. I could hardly exaggerate his influence among the negroes; glib of tongue, he swayed them to his purpose whether for good or evil; in a word, he was their idol. On one occasion he was delivering a very radical speech in which he referred to the paper which we were editing as that “dirty little sheet.” He was correct as to the word “little,” for it was not much larger than a good size pocket handkerchief; but it was exceedingly warm, a fact which had excited his ire. The next day, being informed by a friend who was present of Meacham’s remark, I called upon him at the post-office and asked an interview. With his usual courtesy he bowed and said he would come over to my office as soon as he had distributed the mail. I cut a stick, carried it up to the office and hid it under my desk. Within an hour he appeared. I told him to take a seat, but I could see that he suspected something unusual as he began to back towards the door. I saw that I was going to lose the opportunity of an interview, so I grabbed the stick and made for him. Now, my office was the upper story of a merchandise building approached on the side by wooden stairs. I hardly think that he touched one of those steps going down; it was a case of aerial navigation to the ground. This gave him the start of me. He was pursued up to the postoffice door and through a street filled with negroes and yet not a hand was raised or word said in his defense, nor was the incident ever noticed by the authorities. The unseen power was behind me. Had I attempted anything of the kind a year before I would have been mobbed or suffered the penalties of the law.

In modern-day Texas, this would be considered aggravated assault — a first-degree felony when committed against a public servant.

Simkins’ active involvement with the Klan may have ended when he and his brother came to Texas and began practicing law in Corsicana in the early 1870s, but his open admiration and promotion of the Klan did not. He continued to be an outspoken champion of the “Invisible Empire” throughout his decades on the faculty in Austin. Simkins’ 1914 Thanksgiving Day speech, excerpted above, was so popular that he gave it again on Thanksgiving the following year, 1915, a date which is widely accepted as the rebirth of the Klan in the 20th century. The speech was subsquently published in the UT alumni magazine, The Alcade.

Professor Simkins’ role as a founder of the Ku Klux Klan in Florida had largely been forgotten until this past spring, when Tom Russell, a law professor at the University of Denver, published a paper (PDF download) on the Klan and its sympathizers as a force that had worked steadily behind the scenes at UT to exclude African American students. Russell had first encountered Simkins’ history when Russell himself had been a faculty member in Austin in the 1990s. Russell presented his paper in March at a conference on the UT campus on the history on integration of the school, and publicly called for Simkins Hall to be renamed. The story was quickly picked up in blogs and editorials, and coverage in the Wall Street Journal and on television news soon followed.

It’s important to remember the time at which the decision was made to name the new dormitory after Professor Simkins. An editorial in the campus newspaper, the Daily Texan, points out that the 1954 decision came just weeks after the Supreme Court issued its famous Brown v. Board of Education ruling. But it’s likely that the regents who considered and approved the move were thinking at least as much about an earlier decision, Sweatt v. Painter (1950), in which a unanimous Supreme Court had rejected Texas’ refusal to admit an African American man, Heman Marion Sweatt, to the University of Texas School of Law on the grounds that there was no other public law school in the state of similar caliber open to African Americans. The Sweatt case was another nail in the coffin of separate-but-equal as enshrined in Plessy, and the State of Texas fought hard against it, going so far as to secure a six-month delay in state court quickly to establish a blacks-only law school at Texas Southern University in Houston — now the Thurgood Marshall School of Law. Considering the rancor that surrounded the Sweatt case — a cross was burned in front of the law school during Sweatt’s first semester — it’s hard to believe that just four years later, when it came time to name the new law school dormitory building, old Professor Simkins’ infamous Thanksgiving lectures, attended by hundreds of enthusiastic and applauding students, had been forgotten.

Russell’s call to remove Simkins’ name from the dorm has generated a lot of interest, and much controversy. Russell has continued to be a strong and steadfast advocate for the change, reminding critics that the issue here is not Simkins’ service as a Confederate officer during the war, but his active involvement with the Klan in the years following, and his enthusiastic support of the violence and intimidation they employed. “Please note that I have no problem with Colonel Simkinsʼs service as a Confederate soldier,” Russell wrote in an opinion piece in The Horn, the UT online news site. “Confederate and Union soldiers alike fought with honor. No one should confuse Confederate soldiers with Klansman. Doing so dishonors the soldiers by equating them with criminals.” I’m not certain, based on his manuscript, that Professor Russell is entirely sincere in drawing a bright line between the conduct of klansmen and wartime Confederates more generally; it may be more of a calculation than a conviction.

Nonetheless, Simkins Hall has got to go.

The Board of Regents is widely expected to accept President Powers’ recommendation to rename Simkins Hall this week. The facility’s new name would be “Creekside Dormitory.”

Additional: At the end of the third-to-last paragraph above, I observed that Professor Russell’s distinction between the action of klansmen like Simkins and Confederate soldiers as a whole was “more of a calculation than a conviction.” After thinking about it a little more, I’m convinced of it, but my comment was somewhat flip and unduly harsh. It’s effective strategy. In adding that short paragraph to his op-ed, Professor Russell takes a necessary and practical step to narrow the focus of his campaign. I have no idea what Russell’s views on the Civil War or the Confederacy are generally, but he very wisely keeps the focus here on Simkins, both his actions as a klansman during Reconstruction and his advocacy for the Klan in the decades that followed. The removal of Simkins’ name from the dorm is an easy case to make, on its own merits; allowing others to redirect the debate into one about the Confederacy (or “political correctness,” or the late Senator Robert Byrd, etc.) is wrong. In three sentences, Russell keeps the focus exactly where it should be in this case, on whether or not a major university should retain the name on one of its dormitories of a man whose explicit and enthusiastically-held actions and attitudes are so entirely out of line with the values the institution stands for. By excluding the Confederacy and the war from his central argument, Russell pares his campaign to its central and essential element, reducing it to a core that is effectively impossible to argue against on its own merits. That’s good lawyering.

Additional, Pt. 2: Tom Russell has a column on this case at the Huffington Post.

12 comments