Private Hobbs’ Diary: “We found in the harbour three Gun boats. . . .”

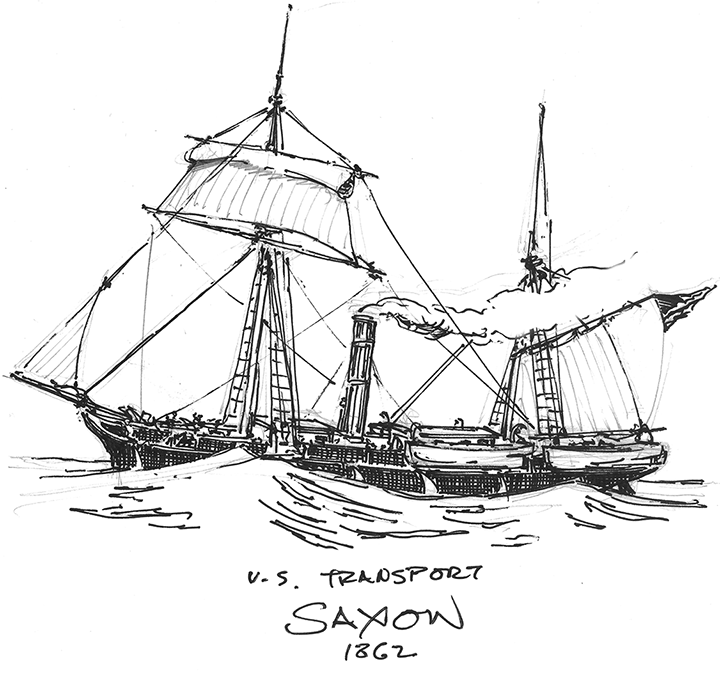

U.S. Army chartered transport Saxon, 1862.

Alexander Hobbs was a private in Company I of the 42nd Massachusetts Infantry. It would be Hobbs’ and his messmates’ misfortune that Company I was one of the three companies of that regiment that eventually occupied Kuhn’s Wharf on the Galveston waterfront, and came under attack by Confederate forces in the early morning hours of New Years Day, 1863. Hobbs kept a diary that encompassed his experiences, which is now part of the collection at the Woodson Research Center at Rice University.

In an earlier post, we traveled along with Hobbs as he and his messmates boarded the chartered transport Saxon [1] at Brooklyn, and made the rough passage down the eastern seaboard, around the Florida Reef, and into the Gulf of Mexico to Ship Island, Mississippi. After a brief stop there for coal, Saxon continues on to the mouth of the Mississippi:

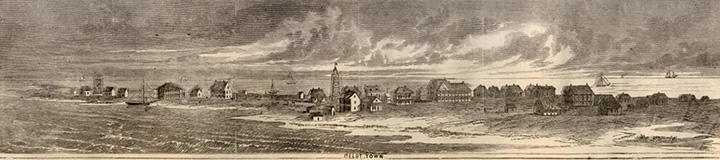

Pilot Town at the mouth of the Southwest Pass of the Mississippi. Harper’s Weekly via SonoftheSouth.net.

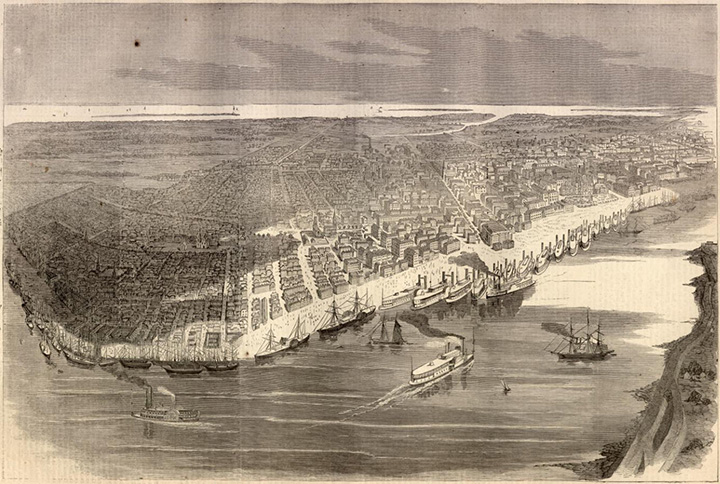

New Orleans, 1862

[1] Saxon was a relatively small, 413-ton screw steamer, built at Brewer, Maine, opposite Bangor on the Penobscot River in 1861. She was first registered at Boston, but would spend much of the Civil War under charter to the U.S. Army as a transport. She would continue in civilian for almost three decades after the war, before being abandoned in 1892. Mitchell, C. Bradford, ed. Merchant Steam Vessels of the United States, 1790–1868 (The Lytle-Holdcamper List), (Staten Island, New York: Steamship Historical Society of America, 1975), 196. [2] Probably the 31st Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. [3] Carrolton was a town upriver from New Orleans from 1833 to 1874, when it was annexed to become part of New Orleans. During the Civil War, Carrolton was somewhat infamous for its various forms of vice, particularly liquor, that caused ongoing discipline problems for the Union military governor, Benjamin Butler. The general’s civilian brother, Andrew, was widely believed to be engaging in all manner of shady business dealings, operating mostly out of Carrolton.

Saxon illustration by Andy Hall

Spoons Butler, Yellow Jack and the Crescent City

Uncle Abe: “Hell! Ben, is that you? Glad to see you!’

Butler: “Yes, Uncle Abe. Got through with that New Orleans Job. Cleaned them out and scrubbed them up! Any more scrubbing to give out?

_____________

Ron Coddington, blogger and author of the Faces of the Civil War series, has a new post up on Union General Benjamin Franklin Butler. Coddington rightly notes that the general “is not remembered especially well by history.” That’s certainly true. Between his ineptitude as a field commander and the vilification of him resulting from the sharp hand he used in the occupation of New Orleans, Butler gets pretty short shrift in most popular accounts. But as Ron points out, Butler — a former Democrat who at that party’s national convention in 1860 supported Jefferson Davis for president of the United States — was transformed by his war experience into a radical Republican and an ardent champion of civil rights for African Americans. He drafted the Ku Klux Klan Act, signed into law by President Grant in 1871, and (with Charles Sumner) wrote the Civil Rights Act of 1875. The latter legislation was subsequently struck down by the Supreme Court, and many of its key provisions were never enacted until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 — nearly eighty years after they were first set out. As Ron observes, “Butler was a man ahead of his time.”

Butler is often cited as the most infamous example of the Union’s “political” generals, men with little or no military experience who were appointed to senior commands based on their political influence in civilian life. His reputation, at least in the South, is defined by his tenure in New Orleans, where he attained the sobriquet “Beast” Butler for his intolerance of any show of disrespect for his occupying soldiers, and his vigorous enforcement of the rules of occupation. (He infamously hanged a Confederate sympathizer for tearing down the Federal flag from the U.S. Mint.) What’s less known, unfortunately, is the remarkable success Butler’s administration of the city had in reducing its infamously-high toll from that scourge of the South, yellow fever. As Andrew McIlwaine Bell explains in Mosquito Soldiers: Malaria, Yellow Fever and the Course of the American Civil War, New Orleans had a long and horrific history with the disease in the decades before the war, particularly in the 1850s, resulting in the deaths of over eighteen thousand people. The vomito negro was particularly hard on immigrants and visitors to the cities from Northern states; the illness was often referred to as the “strangers’ disease.” Butler was well aware of New Orleans’ reputation as a sickly city, and immediately set out to do something about it.

After consulting with his medical staff and a few local doctors (some of whom were openly hostile), Butler decided that yellow fever was an imported malady that required local unsanitary conditions to survive. As a result, he chose to implement simultaneously the two strategies best known at the time for preventing the spread of the disease-a strict quarantine and fastidious sanitation measures. A quarantine station was set up seventy miles below the city and its officers given firm orders to detain any potentially infected vessels for forty days. In addition, a local physician was appointed to inspect incoming ships at the station and was threatened with execution if any vessels known to be carrying yellow fever were allowed to proceed upriver. These new rules caused a minor diplomatic row with the Spanish; who believed that their ships arriving from Cuba (where yellow fever was endemic) were being unfairly targeted for lengthy detentions. Butler assured Senor Juan Callejon, Her Catholic Majesty’s consul in New Orleans, that he was not imposing “any different quarantine upon Spanish vessels sailing from Havana.” To the relief of the State Department, Spain eventually dropped the matter but not before firing off a few strongly worded communiques.

In town Butler put an army of laborers to work round the clock flushing gutters, sweeping debris, and inspecting sites thought to be unclean such as stables, “butcheries;’ and New Orleans’s many “haunts of vice and debauchery.” Steam-powered pumps siphoned stagnant water from basins and canals into nearby bayous. The northern press picked up the story and ran articles praising Butler’s methods. “He will probably demonstrate before the year is out that yellow fever, which has been the scourge of New Orleans, has been merely the fruit of native dirt, and that a little Northern cleanliness is an effectual guarantee against it,” predicted the editors at Harper’s Weekly. The magazine published a cartoon five months later which featured the general holding a soap bucket and scrub brushes in front of an approving Abraham Lincoln.

In addition to cleaning up the place, Butler also imposed a strict quarantine. How effective were Butler’s efforts? According to Bell, during the fever season of 1862 — the hottest months of late summer and early fall, ending with the first cold front — the number of fatalities to yellow fever in the Crescent City were two.

Such a small number is hard to credit, but it appears to be true. Furthermore, deaths remained astonishingly low during the next three years of Federal military occupation. A total of eleven New Orleanians died of yellow fever between 1862 and 1865. The year following the war, when the city was reopened to trade and immigration and local control was returned to civilian authorities under Reconstruction, 185 died. The following year, 3,107. New Orleans quickly slipped back into its old, antebellum pattern of mild years punctuated by terrible epidemics; over four thousand died in 1878, and the following year the disease famously claimed the life of former General John Bell Hood, his wife and one of his eleven children.

Such a small number is hard to credit, but it appears to be true. Furthermore, deaths remained astonishingly low during the next three years of Federal military occupation. A total of eleven New Orleanians died of yellow fever between 1862 and 1865. The year following the war, when the city was reopened to trade and immigration and local control was returned to civilian authorities under Reconstruction, 185 died. The following year, 3,107. New Orleans quickly slipped back into its old, antebellum pattern of mild years punctuated by terrible epidemics; over four thousand died in 1878, and the following year the disease famously claimed the life of former General John Bell Hood, his wife and one of his eleven children.

Today, Ben Butler is too often viewed as a curious admixture of ogre and buffoon, something of a cross between William Tecumseh Sherman and Oliver Hardy. But the reality is, as always, more complex. Whatever else one may say about his hard-handed rule in New Orleans, there’s little doubt that his efforts in both enforcing a quarantine and cleaning up the city made a tremendous difference, and saved many lives that would have a been lost otherwise even in a “mild” year.

____________________

Image: Harper’s Weekly, 1863, via Abraham Lincoln’s classroom; tomb of Sercy (newborn), Mary Love (22 months) and Edwin Given Ferguson (4 years), who died of yellow fever in New Orleans on August 30 and 31, 1878, via NOLA Graveyard Rabbit.

1 comment