Real Confederates Didn’t Know About Black Confederates

Lots of folks are familiar with Howell Cobb’s famous line, offered in response to the Confederacy’s efforts to enlist African American slaves as soldiers in the closing days of the war: “if slaves make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” It was part of a letter sent to Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon, in January 1865:

The proposition to make soldiers of our slaves is the most pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began. It is to me a source of deep mortification and regret to see the name of that good and great man and soldier, General R. E. Lee, given as authority for such a policy. My first hour of despondency will be the one in which that policy shall be adopted. You cannot make soldiers of slaves, nor slaves of soldiers. The moment you resort to negro [sic.] soldiers your white soldiers will be lost to you; and one secret of the favor With which the proposition is received in portions of the Army is the hope that when negroes go into the Army they will be permitted to retire. It is simply a proposition to fight the balance of the war with negro troops. You can’t keep white and black troops together, and you can’t trust negroes by themselves. It is difficult to get negroes enough for the purpose indicated in the President’s message, much less enough for an Army. Use all the negroes you can get, for all the purposes for which you need them, but don’t arm them. The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong — but they won’t make soldiers. As a class they are wanting in every qualification of a soldier. Better by far to yield to the demands of England and France and abolish slavery and thereby purchase their aid, than resort to this policy, which leads as certainly to ruin and subjugation as it is adopted; you want more soldiers, and hence the proposition to take negroes into the Army. Before resorting to it, at least try every reasonable mode of getting white soldiers. I do not entertain a doubt that you can, by the volunteering policy, get more men into the service than you can arm. I have more fears about arms than about men, For Heaven’s sake, try it before you fill with gloom and despondency the hearts of many of our truest and most devoted men, by resort to the suicidal policy of arming our slaves.

No great surprise here; earnest and vituperative opposition to the enlistment of slaves in Confederate service was widespread, even as the concussion of Federal artillery rattled the panes in the windows of the capitol in Richmond.

What’s passing strange, as Molly Ivins used to say, is that Howell Cobb is a central figure in one of the canonical sources in Black Confederate “scholarship,” the description of the capture of Frederick, Maryland in 1862, published by Dr. Lewis H. Steiner of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. In his account of the capture and occupation of the town, Steiner makes mention of

Over 3,000 Negroes must be included in this number [of Confederate troops]. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the Negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie-knives, dirks, etc. . . and were manifestly an integral portion of the Southern Confederate Army.

This passage is often repeated without critique or analysis, and offered as eyewitness evidence of the widespread use of African American soldiers by the Confederate Army. Indeed, Steiner’s figure is sometimes extrapolation to derrive an estimate of black soldiers in the whole of the Confederate Army, to number in the tens of thousands.

But, as history blogger Aporetic points out, Steiner’s observation is included in a larger work that mocks the Confederates generally, is full of obvious exaggerations and caricatures, and is clearly written — like Frederick Douglass’ well-known evocation of Black Confederates “with bullets in their pockets” — to rally support in the North to the Union cause. It is propaganda. Most important, Steiner’s account of Black Confederates under arms is entirely unsupported by other eyewitnesses to this event, North or South. Aporetic goes on to point out the apparent incongruity of Steiner’s description of this horde being led by none other than Howell Cobb:

A drunken, bloated blackguard on horseback, for instance, with the badge of a Major General on his collar, understood to be one Howell Cobb, formerly Secretary of the United States Treasury, on passing the house of a prominent sympathizer with the rebellion, removed his hat in answer to the waving of handkerchiefs, and reining his horse up, called on “his boys” to give three cheers. “Three more, my boys!” and “three more!” Then, looking at the silent crowd of Union men on the pavement, he shook his fist at them, saying, “Oh, you d—d long-faced Yankees! Ladies, take down their names and I will attend to them personally when I return.” In view of the fact that this was addressed to a crowd of unarmed citizens, in the presence of a large body of armed soldiery flushed with success, the prudence — to say nothing of the bravery — of these remarks, may be judged of by any man of common sense.

The Black Confederate crowd doesn’t usually include this second passage describing the same event, or explain Cobb’s apparent profound amnesia when it comes to the employment of African Americans in Confederate ranks. How is it, one wonders, that the same Howell Cobb who supposedly led thousands of black Confederate soldiers into Frederick in 1862 found the very notion of enlisting African Americans into the Confederate military a “most pernicious idea” just twenty-seven months later? How is it that the general who called on his black troops to give three cheers, then “three more, my boys!” came to believe that “the day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution?” How is it that the commander of successful black soldiers felt that “as a class they are wanting in every qualification of a soldier?”

But set aside Dr. Steiner’s propogandist account for the moment; it’s unreliable and unsupported by other sources. Events at Frederick aside, how is that Howell Cobb, in January 1865, was unaware of the thousands, or tens of thousands, of African Americans soldiers supposedly serving in Confederate ranks across the South?

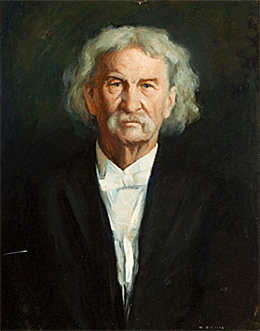

Howell Cobb’s Confederate bona fides are unimpeachable, and throughout the war he was irrevocably tied in to both political and military affairs. In his career he was, in turn, a five-term U.S. Representative from Gerogia, Speaker of the U.S. House Representatives, Governor of Georgia, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Speaker of the Provisional Confederate Congress, and Major General in the Confederate Army. He was a leader of the secession movement, and was elected president of the Montgomery convention that drafted a constitution for the new Confederacy. For a brief period in 1861, between the establishment of the Confederate States and the election of Jefferson Davis as its president, Speaker Cobb served as the new nation’s effective head of state. In his military career, Cobb held commands in the Army of Northern Virginia and the District of Georgia and Florida. He scouted and recommended a site for a prisoner-of-war camp that eventually became known as Andersonville; his Georgia Reserve Corps fought against Sherman in his infamous “March to the Sea.” Cobb commanded Confederate forces in a doomed defense of Columbus, Georgia in the last major land battle of the war, on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865, the day after Abraham Lincoln died in Washington, D.C. Perhaps more than any other man, Howell Cobb’s career followed the fortunes of Confederacy — civil, political and military — from beginning to end.

Howell Cobb’s Confederate bona fides are unimpeachable, and throughout the war he was irrevocably tied in to both political and military affairs. In his career he was, in turn, a five-term U.S. Representative from Gerogia, Speaker of the U.S. House Representatives, Governor of Georgia, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Speaker of the Provisional Confederate Congress, and Major General in the Confederate Army. He was a leader of the secession movement, and was elected president of the Montgomery convention that drafted a constitution for the new Confederacy. For a brief period in 1861, between the establishment of the Confederate States and the election of Jefferson Davis as its president, Speaker Cobb served as the new nation’s effective head of state. In his military career, Cobb held commands in the Army of Northern Virginia and the District of Georgia and Florida. He scouted and recommended a site for a prisoner-of-war camp that eventually became known as Andersonville; his Georgia Reserve Corps fought against Sherman in his infamous “March to the Sea.” Cobb commanded Confederate forces in a doomed defense of Columbus, Georgia in the last major land battle of the war, on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865, the day after Abraham Lincoln died in Washington, D.C. Perhaps more than any other man, Howell Cobb’s career followed the fortunes of Confederacy — civil, political and military — from beginning to end.

And yet, after almost four years of war and almost three years of commanding large formations of Confederate troops in the field, in January 1865 Howell Cobb seemingly remained unaware of the thousands, or tens of thousands, of African Americans now claimed to have been serving in Southern ranks throughout the war.

It is passing strange, is it not?

The Nazi Fanboys

There are exactly four blogs on the intertubes that haven’t addressed the recent revelation that a candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives in Ohio is a military reenactor. Specifically, a World War II German reenactor. More specifically still, an S-freaking-S reenactor, from a unit that has been implicated in serious war crimes. Make that three blogs, because I’m now putting down some of my own thoughts on the matter.

Not long ago, Josh Green of The Atlantic broke a story that Rich Iott (left), the GOP nominee for Ohio’s 9th Congressional District (Toledo), was for three years (2004-07) a reenactor with Wiking Division, a group of World War II reenactors based in the Upper Midwest. Iott is a long-time reenactor, but the fact that he spent a few years play-acting a Nazi is, understandably, a political bombshell. Though he was always a long-shot in the general election — he’s running against a long-time Democratic incumbent, Marcy Kaptur, in a deep-blue district — the Wiking revelation effectively puts paid to this and any future campaign Mr. Iott may be considering.

Not long ago, Josh Green of The Atlantic broke a story that Rich Iott (left), the GOP nominee for Ohio’s 9th Congressional District (Toledo), was for three years (2004-07) a reenactor with Wiking Division, a group of World War II reenactors based in the Upper Midwest. Iott is a long-time reenactor, but the fact that he spent a few years play-acting a Nazi is, understandably, a political bombshell. Though he was always a long-shot in the general election — he’s running against a long-time Democratic incumbent, Marcy Kaptur, in a deep-blue district — the Wiking revelation effectively puts paid to this and any future campaign Mr. Iott may be considering.

In the political scheißesturm that followed, the Wiking group rallied some support from other reenactor groups, including this statement from the Mid-Michigan Chapter of the 82nd Airborne Division Association, which accuses Iott’s critics as playing a “twisted political game” and perpetrating a “blatant lie:”

Reenactors reflect every nation involved in WWII. We have seen not only American and German reenactors, but British, Dutch, French, Polish, Russian, Japanese, Italian and a host of others. To use an educational hobby which provides a teaching tool for all Americans in some twisted political game is not only omitting the true facts, but a blatant lie by conversion of the truth.

They doth protest too much. One of my uncles was a member of the 101st Airborne Division during World War II. I don’t know many details of his service; he died when I was little and he didn’t talk to other family members about those parts of the war. But I know that he witnessed the liberation of some of the concentration camps they discovered at the end of the war. (It may have been a situation like that depicted in Band of Brothers; I don’t really know.) I have no idea how he would’ve viewed modern hobbyists recreating American airborne troops, but it’s impossible for me to believe that he would’ve had any use at all for Rich Iott and his Wiking reenactor buddies.

Rich Iott is not a Nazi. But the objective evidence is that, as a practical matter, he is an imbecile, ein schwachkopf, and that he and his Wiking kameraden are willfully ignoring the very ugly history of the unit they model themselves after. It’s a degree of intentional compartmentalization that’s just staggering. They aren’t Holocaust deniers, who are (for better or worse) straight up about their beliefs; they’re something more insidious, folks for whom it just doesn’t much register. Of all the World War II German military formations, these guys have chosen to recreate the SS, and specifically a unit, the Wiking Division, that was recruited in the occupied countries in the West — Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands — to be composed of men of similar Aryan characteristics to the German SS, or “related stock,” as Himmler put it. The division was explicitly recruited to serve in the East; the antisemitic underpinnings of the SS are explicit in the division’s recruiting materials. Recruiting posters, printed in the local language, sought volunteers to join the fight against Bolshevism, which — inevitably — the Nazis intentionally conflated with Judaism. It’s very ugly stuff, and the Wiking Division was in the center of it, including putting down the Warsaw Uprising in the fall of 1944.

Just last year, a former member of the Wiking Division was charged with atrocities:

A 90-year-old former member of an elite Waffen SS unit has been charged with killing 58 Hungarian Jews who were forced to kneel beside an open pit before being shot and tumbling into their mass grave.

The man, named in the German press as Adolf Storms, becomes the latest pensioner to be prosecuted for alleged Nazi war crimes as courts rush to secure convictions before the defendants become too infirm and the witness testimony too unreliable.

Mr Storms was found by accident last year, as part of a research project by Andreas Forster, a 28-year-old student at the University of Vienna. . . .

Mr Storms was a member of the 5th Panzer Wiking Division which fought on the Eastern Front, moving through Ukraine into the Caucasus, taking part in a bloody fight for Grozny and the tank battles of Kharkov and Kursk before wheeling back through Eastern Europe. By most accounts it left a trail of bodies behind.

By the spring of 1945 the unit was heading to Austria with the intention of surrendering to the Americans rather than to the Red Army.

But first the Wiking Division, led in the early days by General Felix Steiner, who is still revered among neo-Nazis, decided to clean up the evidence against it and eliminate the slave labourers who had dug its fortifications and defensive lines.

According to a statement issued by the regional court in Duisburg, where Mr Storms has spent most of his retirement, 57 of the 58 victims were killed near the Austrian village of Deutsch Schuetzen. The mass grave there was excavated in 1995 by the Austrian Jewish association and the bodies given proper funerals.

Storms died in June 2010, before he could go to trial.

Robert M. Citino of the Military History Center at the University of North Texas, hit the nail on the head when he pointed to what he sees as “an adolescent crush” on Nazi history. He goes on to summarize it nicely in a short essay on HistoryNet:

What you often hear is that the [Wiking] division was never formally accused of anything, but that’s kind of a dodge. The entire German war effort in the East was a racial crusade to rid the world of ‘subhumans,’ Slavs were going to be enslaved in numbers of tens of millions. And of course the multimillion Jewish population of Eastern Europe was going to be exterminated altogether. That’s what all these folks were doing in the East. It sends a shiver up my spine to think that people want to dress up and play SS on the weekend.

I don’t buy for a moment that these reenactors are naive innocents who had no idea that their weekend warrior games were simply beyond the pale of polite company; their reenactor website clearly shows otherwise. It’s been heavily scrubbed in the last few days — including removal of event pictures dating back to Iott’s time with them — but archived copies are still available, including this one from August 2007, the year Iott reportedly was last a participant. None of the reenactors are identified by their real names, including the Wiking group’s public contacts. Iott is included as “Reinhard Pferdmann,” and all the other group member identify only under similar alter-ego names. They are hiding, because they know, they understand, how offensive their identification with the Wiking Division is, and they don’t want to have to answer for it. I’ve known a lot of reenactors, and visited lots of reenactor websites, and never encountered one (including Confederate reenactors) who didn’t identify at least the key members of the group publicly. To me, that’s prima facie evidence that these guys knew very well how their hobby was perceived by the public at large, and (unlike most reenactors) very clearly didn’t want to be publicly associated with it. Iott and his buddies know damn well what they’re doing, and why it’s deeply offensive to so many; that’s why they cower behind names like “Reinhard Pferdmann.” Unlike the Waffen-SS men they so admire, these modern reenactors clearly lack the courage of their convictions.

Twenty-some years ago a Civil War reenactor I knew– he was part of a Union artillery battery — cautioned me that “Civil War reenacting is the lunatic fringe of living history.” His observation was tongue-in-cheek, but endearing. I’ve known a lot of reenactors over the years, and often toyed with the idea of diving into the hobby myself. (Much to the relief of both my wife and my wallet, the feeling passes after a few days.) Reenacting has a lot of appeal, and I think it lends itself well to helping educate the public in certain areas. Reenactors particularly excel in explaining the details of daily life, civilian and military, in earlier times. While it seems unlikely that I’ll be putting on a period uniform myself, I get the appeal, and I understand how folks become so devoted to it.

But there’s something fundamentally different about what Iott and his buddies are up to. They are not exploring their own nation’s history, or their family’s, as many Civil War reenactors are. Their open admiration for the Waffen SS — specifically, a Waffen SS division composed of men who betrayed their own fellow Dutch, Belgian, Norwegian citizens and went over to the enemy — is simply unfathomable. (Later in the war, from 1943 on, some Waffen SS men were conscripted from the occupied countries.) It is reprehensible, and they know it; that’s why they hide behind character names. There are thousands of survivors of the Holocaust and Nazi atrocities on the Eastern Front still living, and millions more of their relatives and friends who have heard firsthand of their experiences and the hands of the Waffen SS and others like them. The Wiking reenactors don’t particularly care about those things, or even acknowledge them; they want to focus entirely on their ehrfurcht gebietend MG42 machine guns — “we also have full automatic weapons for rent!” — and downloadable food tin labels. The people aren’t doing history, or education; they’re getting their jollies at playing at being Nazis. They give living history and historical reenacting a bad name. That they don’t own up to their identities online shows that, on some level, they’re embarrassed by what they do. As they should be.

If Rich Iott wants to play dress-up as a member of the Waffen SS, an organization that was declared criminal at the Nuremberg Trials, and simulate a unit that has been implicated in numerous war crimes, then he is free to do so. The rest of us are free to call him out for it. They want to run around playing Waffen-SS, but not be held accountable for it, individually or as a group. Note to the Wiking kameraden; if your hobby is such an embarrassment that you don’t want others to know about it, do us all a favor and get another damned hobby.

Coates’ Civil War

As some of you are aware, over the last several months we’ve had long, intricate discussions of the Civil War and the Civil War period over at Ta-Nehisi Coates’ blog at The Atlantic. These have dealt with diverse subjects, from current-events issues like the Virginia Confederate History Month debacle last spring, to an ongoing group-read of MacPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom. It’s a discussion that I’ve had the chance to contribute to in a small way, and it’s helped to both challenge and clarify my own thinking about the war and its continuing legacy.

As some of you are aware, over the last several months we’ve had long, intricate discussions of the Civil War and the Civil War period over at Ta-Nehisi Coates’ blog at The Atlantic. These have dealt with diverse subjects, from current-events issues like the Virginia Confederate History Month debacle last spring, to an ongoing group-read of MacPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom. It’s a discussion that I’ve had the chance to contribute to in a small way, and it’s helped to both challenge and clarify my own thinking about the war and its continuing legacy.

Now, one of the regulars there who goes by the handle Absurdbeats has assembled a compliation of Civil War related posts from Coates’ place, going back over two years. Both the posts themselves and the discussions that follow are often both fascinating and illuminating. I’m also adding this listing in the links at right.

Happy reading, folks.

A Hot Mess of Historiography

I haven’t written much here about the new book by Ann DeWitt and Kevin M. Weeks, Entangled in Freedom, a novel for young people. The book’s protagonist, Isaac Green, is a young black slave in Civil War Georgia who follows his master into the Confederate Army and, by virtue of having memorized the Bible, quickly finds himself voted by the white soldiers to be the regimental chaplain. I’ve tried to avoid the subject in part because Levin has been all over it since the book was announced, and partly because I had intended to publish here an e-mail interview with Ms. DeWitt, trying to get at some of her background and thinking in writing and publishing the work. I contacted her a couple of weeks ago asking if she’d be willing, and she promptly responded positively. But I got lazy and didn’t send her my questions and, in the meantime, the debate over the book has intensified considerably. Last month Mr. Weeks sent a copy of the book and an angry letter to Levin’s employer — very bad form, that — accusing Levin of “slander” and trying to have the book “silenced.” In the back-and-forth that’s followed, both on Levin’s site and Ms. DeWitt’s, both sides have laid out their cases (and likely will continue to do so), and I’m not sure that there’s any point now in doing the e-mail interview. I don’t think it will illuminate much, since neither “side” in the debate is even speaking the other’s language.

Here is what I mean about not speaking each other’s language: Levin’s (and others’) criticisms of the book — what’s known of it — revolved entirely around the historicity of it, how well the fictional story fits within the known historical framework of that time and place. In response, Ms. DeWitt counters with a response outlining her values and motivations in writing the book:

Imagine writing a novel for young adults which (1) espouses the sanctity of marriage, (2) does not contain profanity, (3) promotes earning ones way in America, (4) advocates true friendship, (5) demonstrates the positive progression of America over the last 150 years, and (6) highlights the strength of the family unit; yet, the novel is dubbed “nonsense” by a recognized Virginia Civil War journalist and historian.

The above six principles are the family narratives of Ann DeWitt. I have no 19th century written documentation of these six family values because they were passed down to me verbally by my ancestors. I do not secretly hide them but proudly share them with the world.

It’s clear that, far from defending the research and historical background presented in the novel, she doesn’t understand the criticism of it. None of those “principles” have anything to do with the historical accuracy of the setting or the plot. One could write such a work in any of a thousand settings, and and frame it in a way that is, if not historically documented, at least plausible. Laura Ingalls Wilder is the obvious example of doing this, although she had the advantage of having actually lived the life she described in her writing.

DeWitt asserts that “these six family values because they were passed down to me verbally by my ancestors.” Okay, fine, but no one’s asking for documentation of her family values. This statement reveals something much more essential here, specifically that, in Ms. DeWitt’s view, criticizing the historical accuracy of the book is criticizing her family, and her values. She sees it not as criticism of her work, but as a personal attack on her. It’s not the same thing at all. I don’t doubt that Ms. DeWitt is a very well-intentioned and sincere person, but having good intentions and a strong moral compass is not enough when it comes to presenting a believable and realistic picture of the past.

Ms. DeWitt and Mr. Weeks haven’t written an historical novel; they’ve written a moral allegory nominally set in the Civil War. But it’s not the South that existed in 1860s or, for that matter, the 1960s. Ms. DeWitt and Mr. Weeks have constructed a Confederacy where wise people “in the Deep South knew all the time that black people are cut from the same board of cloth as whites,” and “knew that slavery wasn’t going to last always.” Alexander Stephens and George Wallace never existed in this version of the American South. Ms. DeWitt and Mr. Weeks have the notion of historical fiction exactly backwards; the goal is to tell a story that fits within the larger, factual context of its setting, not to create a fictional history that supports the particular story one wants to tell for other reasons.

The passage Levin posted recently shows that the historical framework for the novel is based largely on Black Confederate factoids and memes culled from the web. Just that one short passage — 648 words — crams in multiple Black Confederate bullet points, strung together by stilted dialogue. Only a tiny percentage of Confederate soldiers owned slaves? Check. Harper’s Weekly reference to black soldiers at Manassas? Check. Loyal slaves will be delivered “a great prize?” Check. Slaves and owners who “get along fine?” Check.

In defending her book and its thesis, Ms. DeWitt has made some extremely odd arguments — so odd or tangential that one might guess that they were meant in jest, though I don’t think they were. She argues — in all sincerity, it seems — that the slaves who went to war with their masters as body servants were the historical equivalent of present-day, college-educated executive assistant, and then extends that analogy further to the entourage that a modern-day U.S. president travels with. She openly wonders why “mark-and-capture,” a technique used to estimate wildlife populations that involves trapping animals, tagging them and releasing them back into the wild to be recaptured and counted at a later date, hasn’t been used to calculate the numbers of Black Confederates. DeWitt does an online search of Confederate pension records from Alabama’s state archives under the surname “Slave” (!), but says cryptically that the archive “does not document if these African-Americans fought for the Union or the Confederate States Army.” DeWitt lists over two hundred men who received “colored” pensions from the State of Tennessee, helpfully adding that “Colored = Black = African-American,” but omits the fact that Tennessee differentiated these from “S” pensions, issued to soldiers. She hints — both on her website and in the novel — that enlistment or service records that do not explicitly identify the subject as white should be taken as de facto evidence of prospective Black Confederates: “CSA enlistment forms and pension applications did not include race, so . . . the world may never know the total number of African-Americans (Blacks) who served in any and all capacities of the American Civil War.” And then there are explanations that are just odd non-sequiturs:

African-Americans want to know their family history for personal as well as medical reasons. We have turned to scientific DNA testing in order to trace our family lineage. As a human being, it is offensive when historians overall imply that my ancestors in South Carolina were not smart enough to band together and run across a field of dying Confederate soldiers to join the Union Army.

As historiography, this is a hot mess. I don’t know Ms. DeWitt; she seems like a very nice, well-intentioned person who’s deeply devoted to her family and its traditions. That’s a good thing, but I fear that she assumes oral tradition, passed from generation to generation, to be sufficient in not only interpreting her own family’s history — I’ve addressed this before with regard to my own Confederate ancestors — but also in understanding the South, the Confederacy and the fundamental nature of the white supremacist slave society the Confederacy was established to protect and promote. The historical world she presents in Entangled in Freedom isn’t based on research or academic study; it’s the product of intuition and her own, deeply-held faith. But those things are not enough, and to frame what’s intended as an uplifting and inspiring personal story within such a farcical historical context does a real disservice to the public generally, and to students particularly.

It’s a missed opportunity.

The Gettysburg Casino

This is a great video, and hits exactly the right chord. For what it’s worth, Matthew Broderick’s g-g-grandfather fought on Culp’s Hill with the 20th Connecticut Infantry. Not sure why this wasn’t mentioned in the video; it’s one of those small details that mean a lot when it comes to making the case for the preservation of Gettysburg.

___________

h/t Kevin Levin.

Now We’re Finally Getting Somewhere.

Over the last few weeks there’s been a good bit of discussion about Ann DeWitt and her website on Black Confederates, particularly since the announcement of a new novel for young adults, written by her and Kevin M. Weeks, Entangled in Freedom. The discussion has been pretty volatile over at Levin’s place — who coulda’ seen that coming? — but I’ve tried to steer a little clear of criticizing Ms. DeWitt personally, because she seems a sincere, if ill-informed, advocate for the idea, and because at this point anything else will be perceived as “piling on.” But now, I think, she’s actually (and unwittingly) done us all a favor, by acknowledging explicitly what skeptics have been saying for a long time: that at the core of Black Confederate lies a definition of the word “soldier” that is so broad, so vague and nebulous that the word can be taken to mean virtually anything, and is applied to any person who had even the remotest connection to the Confederate army.

This morning, I noticed her project home page now opens with a definition:

Merriam Webster Dictionary defines a soldier as a militant leader, follower, or worker.

If we’re going to quote the dictionary, let’s be clear: she’s quoting the secondary, alternate definition. By citing it, Ms. DeWitt tacitly acknowledges that the primary definition of the word — “a: one engaged in military service and especially in the army b : an enlisted man or woman c : a skilled warrior” — does not generally apply, or is at least too narrow to describe, Black Confederates as she identifies them. It is not too much to say, I think, that in citing such a broad definition, Ms. DeWitt just knocked over the whole house of cards that comprises most of the “evidence” for Black Confederates.

There’s an old saying that a “gaffe” is what happens when a politician accidentally speaks the truth. This is a gaffe. This is the truth that forms the foundation of most Black Confederate advocacy. To qualify as a Black Confederate, one needs only to qualify as a follower or a worker. In short, the term “soldier” applies to anyone — enlisted man, musician, teamster, body servant, cook, hospital orderly, laundress, sutler, drover, laborer, anyone — involved with the army in any capacity.

A long time ago, I learned a rule that has stood me in good stead ever since: any time a writer or public speaker starts off his or her essay by quoting a definition from the dictionary, you can safely stop reading or listening, because nothing worthwhile or new is likely to follow. That’s still true, but it this case Ms. DeWitt’s use of the technique does do us all a genuine service, by admitting what Black Confederate skeptics have been saying all along — that the movement’s advocates are so loose with the their definitions, so willing to conflate service as a volunteer, enlisted soldier under arms with a slave’s compelled service as a cook and body servant to his owner and master, that the narratives they offer cannot stand close historiographical scrutiny at all. To borrow an analogy allegedly coined by Lincoln himself, Black Confederate advocacy is like shoveling fleas across the barnyard — you start with what seems to be a shovelful, but by the time you get to the other side, there’s very little actually there.

Update, August 22: I just noticed this on the website, as well:

Another challenge is the fact that 19th century CSA enlistment forms and pension applications did not include race, so unless all current SCV members come forward with more historical accounts, the world may never know the total number of African-Americans (Blacks) who served in any and all capacities of the American Civil War.

If I’m reading this correctly, Ms. DeWitt views any Confederate enlistment or pension document that doesn’t explicitly state otherwise to be potential evidence of a Black Confederate. Wowza!

Not sure what the call for “all current SCV members come forward with more historical accounts” means.

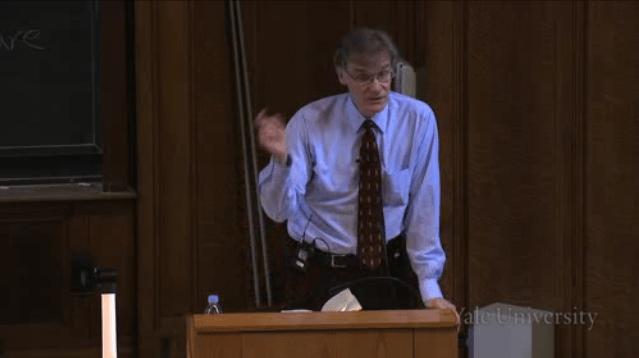

David Blight’s “The Civil War and Reconstruction Era, 1845-1877”

For anyone not familiar with the work of David Blight, you could do worse than to spend some time in the audience for his undergraduate course, recorded during the spring semester of 2008. I had some great instructors — Roger Bilstein, Maury Darst and Alex Pratt, I’m lookin’ at y’all — but none like this. If you watch the entire series, you won’t get academic credit, but you’ll sure get an education.

“We are all officers now!”

Almost a hundred years ago, an old Texas veteran with the improbable name of Valerius Cincinnatus Giles passed away, leaving a sprawling, fragmentary memoir of his Civil War service. A half-century and a lot of editing later, it was finally compiled and published as Rags and Hope, a volume that has since become a classic among Civil War enlisted soldiers’ autobiographies. In closing Giles wrote:

It is over, and we are all officers now!

It’s General That and Colonel This

And Captain So and So.

There’s not a private in the list

No matter where you go.The men who fought the battles then,

Who burned the powder and lead,

And lived on hardtack made of beans

Are promoted now—or dead.

I suspect that, in writing these lines, Giles may have been thinking of a relative of mine, Lawrence Daffan. They must have known each other well. Both served in the Fourth Texas Infantry (Giles in Co. B; Daffan in Co. G), both were captured within a few weeks of each other in late 1863 during the Chattanooga Campaign, and both were active in veterans’ organizations after the war. Lawrence’s daughter Katie, who was prominent in UDC activities and served at the time as superintendent of the Confederate Woman’s Home in Austin, made a big show at Giles’ funeral of placing a small Confederate flag in the dead man’s hands. Cou’n Katie always did have a flair for dramatic gestures.

But beyond Giles’ amusing (and somewhat poignant) rhyme, Daffan is a perfect example of the pitfalls that await the modern researcher, and it underscores the importance of searching out contemporary records. In Lawrence Daffan’s case, everyone in the family “knew” that he had served as an officer, and even his obituary gave his name as “Col. L. A. Daffan.”

But he was never actually an officer. In fact, he wasn’t even a non-com. He was a buck private from the day he enlisted in March 1862 to the day he was released from the PoW camp at Rock Island, Illinois in 1865. He came to be known as “Colonel” Daffan because he was active in veterans’ groups after the war, and the UDC gave him that as an honorary title. He apparently liked it, and used it, to the extent that by the time he died in 1907, everyone in town as well as his family “knew” that he’d served as an officer. Lots of contemporary publications repeat the title. That was accepted as a given for over a century until, just recently, I bothered to look up his actual service record and discovered it wasn’t true.

This is important to would-be researchers because in Daffan’s case, because family oral tradition, Daffan’s obituary and other postwar sources all confirm one another, that he was a former officer. But he wasn’t, and one has to go back to the original records to determine that.

So genealogists and would-be historians, perform due diligence. Don’t assume you “know” something about your ancestor unless you can document it, because there’s a good chance you’re wrong. Do the research. Your work will be better for it when you do.

Image: Veterans of the Philadelphia Brigade Association and the Pickett’s Division Association shake hands across the stone wall over which they’d fought fifty years before, July 3, 1913. Pennsylvania State Archives.

Simkins Hall Update

From the Houston Chronicle:

The University of Texas’ governing board voted unanimously this morning [Thursday, July 15] to rename a dormitory and park named after former leaders of the Ku Klux Klan. . . .

The new names will be Creekside Residence Hall and Creekside Park.

The dormitory, built in 1955 on the banks of Waller Creek, was named for William Stewart Simkins, who taught at the law school from 1899 to 1929 and previously had been a leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Florida.

The park had been named for Simkins’ brother, former UT regent Judge Eldred Simkins, who also was involved with the Klan.

Good move. Some have argued that changing the name of the dorm is an attempt to cover up or deny an ugly historical fact — “history is history,” they say. That’s wrong. This move is exactly the opposite, in that it exposes a more complete view of both the Simkins brothers and the University of Texas in the first half of the 20th century. Professor Simkins contributed a great deal to the early university. That is widely recognized, and will not change. But he brought with that a shameful and hateful advocacy for racial violence and intimidation. He never repudiated that; in fact, he reveled in it. That is not something that should be honored, and you cannot honor the man without honoring the whole man. And in the Simkins brothers’ case, theirs is a deeply disturbing legacy.

William Stewart Simkins, the Klan and the Law School

On Friday, University of Texas at Austin President William Powers Jr. issued a statement calling on the university’s Board of Regents to change the name of Simkins Hall, a dorm for graduate and law students. The dorm, built in the 1950s, is named for a famed UT law professor who was a Confederate officer and, as a recent publication points out, a senior leader of the Ku Klux Klan in Florida during Reconstruction and a lifelong, unabashed defender of the “Invisible Empire” throughout his later tenure at the university. The Board of Regents is likely to consider the president’s recommendation at a meeting this week.

William Stewart Simkins (1842-1929) was a well-known member of the faculty at the University of Texas, teaching there from 1899 to 1929. Although he officially attained emeritus status in 1923, he continued to lecture weekly until his death. “Colonel Simkins,” as he was sometimes called, was a memorable teacher, and something of a character. He was grumpy and irritable. He drank whiskey and once got into a famous argument with the temperance leader Carrie Nation. “Many students were scared of him,” one old alum wrote, “but I always got on well with him and did well in his class.”

William Stewart Simkins (1842-1929) was a well-known member of the faculty at the University of Texas, teaching there from 1899 to 1929. Although he officially attained emeritus status in 1923, he continued to lecture weekly until his death. “Colonel Simkins,” as he was sometimes called, was a memorable teacher, and something of a character. He was grumpy and irritable. He drank whiskey and once got into a famous argument with the temperance leader Carrie Nation. “Many students were scared of him,” one old alum wrote, “but I always got on well with him and did well in his class.”

Simkins was a South Carolinian by birth, and enrolled at the Citadel in the years just before the outbreak of the Civil War. In January 1861, it was Cadet Simkins who sounded the alarm when lookouts sighted Star of the West, a civilian steamer sent by the Buchanan administration to bring supplies to the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter. (Some contemporary accounts credit Simkins with firing the initial gun, widely recognized as the first shot of the Civil War.) Simkins was subsequently commissioned as an artillery officer in a South Carolina battery, participated in the defense of Charleston Harbor in 1863, and ended the war in 1865 as a colonel.

After the war, Simkins settled in Florida, where he and his older brother, Eldred James Simkins (1838-1903), soon helped organize that state’s Ku Klux Klan. By his own admission, William Stewart Simkins played a central role in coordinating that organization’s violence and intimidation against both white “carpetbaggers” and African Americans who challenged the prewar social or political order. Simkins not only acknowledged his role in the Klan’s violent activities, he fairly bragged about his own deeds. In an infamous speech he gave fifteen years after joining the UT faculty — and a half-century after the war — Simkins told of how he ambushed an African American state senator who had spoken out publicly against Simkins’ and his friends’ publication of a anti-Reconstructionist newspaper:

Now in the same town there was a negro [sic.] by the name of Robert Meacham who was. . . brought up as a domestic servant in a refined Southern family and absorbed much of the courteous manner of the old regime. He had been highly honored by the Republican party; in fact, had been made temporary chairman of the so-called Constitutional Convention heretofore referred to. He was at the time of which I am now speaking State Senator and Postmaster in the town. I could hardly exaggerate his influence among the negroes; glib of tongue, he swayed them to his purpose whether for good or evil; in a word, he was their idol. On one occasion he was delivering a very radical speech in which he referred to the paper which we were editing as that “dirty little sheet.” He was correct as to the word “little,” for it was not much larger than a good size pocket handkerchief; but it was exceedingly warm, a fact which had excited his ire. The next day, being informed by a friend who was present of Meacham’s remark, I called upon him at the post-office and asked an interview. With his usual courtesy he bowed and said he would come over to my office as soon as he had distributed the mail. I cut a stick, carried it up to the office and hid it under my desk. Within an hour he appeared. I told him to take a seat, but I could see that he suspected something unusual as he began to back towards the door. I saw that I was going to lose the opportunity of an interview, so I grabbed the stick and made for him. Now, my office was the upper story of a merchandise building approached on the side by wooden stairs. I hardly think that he touched one of those steps going down; it was a case of aerial navigation to the ground. This gave him the start of me. He was pursued up to the postoffice door and through a street filled with negroes and yet not a hand was raised or word said in his defense, nor was the incident ever noticed by the authorities. The unseen power was behind me. Had I attempted anything of the kind a year before I would have been mobbed or suffered the penalties of the law.

In modern-day Texas, this would be considered aggravated assault — a first-degree felony when committed against a public servant.

Simkins’ active involvement with the Klan may have ended when he and his brother came to Texas and began practicing law in Corsicana in the early 1870s, but his open admiration and promotion of the Klan did not. He continued to be an outspoken champion of the “Invisible Empire” throughout his decades on the faculty in Austin. Simkins’ 1914 Thanksgiving Day speech, excerpted above, was so popular that he gave it again on Thanksgiving the following year, 1915, a date which is widely accepted as the rebirth of the Klan in the 20th century. The speech was subsquently published in the UT alumni magazine, The Alcade.

Professor Simkins’ role as a founder of the Ku Klux Klan in Florida had largely been forgotten until this past spring, when Tom Russell, a law professor at the University of Denver, published a paper (PDF download) on the Klan and its sympathizers as a force that had worked steadily behind the scenes at UT to exclude African American students. Russell had first encountered Simkins’ history when Russell himself had been a faculty member in Austin in the 1990s. Russell presented his paper in March at a conference on the UT campus on the history on integration of the school, and publicly called for Simkins Hall to be renamed. The story was quickly picked up in blogs and editorials, and coverage in the Wall Street Journal and on television news soon followed.

It’s important to remember the time at which the decision was made to name the new dormitory after Professor Simkins. An editorial in the campus newspaper, the Daily Texan, points out that the 1954 decision came just weeks after the Supreme Court issued its famous Brown v. Board of Education ruling. But it’s likely that the regents who considered and approved the move were thinking at least as much about an earlier decision, Sweatt v. Painter (1950), in which a unanimous Supreme Court had rejected Texas’ refusal to admit an African American man, Heman Marion Sweatt, to the University of Texas School of Law on the grounds that there was no other public law school in the state of similar caliber open to African Americans. The Sweatt case was another nail in the coffin of separate-but-equal as enshrined in Plessy, and the State of Texas fought hard against it, going so far as to secure a six-month delay in state court quickly to establish a blacks-only law school at Texas Southern University in Houston — now the Thurgood Marshall School of Law. Considering the rancor that surrounded the Sweatt case — a cross was burned in front of the law school during Sweatt’s first semester — it’s hard to believe that just four years later, when it came time to name the new law school dormitory building, old Professor Simkins’ infamous Thanksgiving lectures, attended by hundreds of enthusiastic and applauding students, had been forgotten.

Russell’s call to remove Simkins’ name from the dorm has generated a lot of interest, and much controversy. Russell has continued to be a strong and steadfast advocate for the change, reminding critics that the issue here is not Simkins’ service as a Confederate officer during the war, but his active involvement with the Klan in the years following, and his enthusiastic support of the violence and intimidation they employed. “Please note that I have no problem with Colonel Simkinsʼs service as a Confederate soldier,” Russell wrote in an opinion piece in The Horn, the UT online news site. “Confederate and Union soldiers alike fought with honor. No one should confuse Confederate soldiers with Klansman. Doing so dishonors the soldiers by equating them with criminals.” I’m not certain, based on his manuscript, that Professor Russell is entirely sincere in drawing a bright line between the conduct of klansmen and wartime Confederates more generally; it may be more of a calculation than a conviction.

Nonetheless, Simkins Hall has got to go.

The Board of Regents is widely expected to accept President Powers’ recommendation to rename Simkins Hall this week. The facility’s new name would be “Creekside Dormitory.”

Additional: At the end of the third-to-last paragraph above, I observed that Professor Russell’s distinction between the action of klansmen like Simkins and Confederate soldiers as a whole was “more of a calculation than a conviction.” After thinking about it a little more, I’m convinced of it, but my comment was somewhat flip and unduly harsh. It’s effective strategy. In adding that short paragraph to his op-ed, Professor Russell takes a necessary and practical step to narrow the focus of his campaign. I have no idea what Russell’s views on the Civil War or the Confederacy are generally, but he very wisely keeps the focus here on Simkins, both his actions as a klansman during Reconstruction and his advocacy for the Klan in the decades that followed. The removal of Simkins’ name from the dorm is an easy case to make, on its own merits; allowing others to redirect the debate into one about the Confederacy (or “political correctness,” or the late Senator Robert Byrd, etc.) is wrong. In three sentences, Russell keeps the focus exactly where it should be in this case, on whether or not a major university should retain the name on one of its dormitories of a man whose explicit and enthusiastically-held actions and attitudes are so entirely out of line with the values the institution stands for. By excluding the Confederacy and the war from his central argument, Russell pares his campaign to its central and essential element, reducing it to a core that is effectively impossible to argue against on its own merits. That’s good lawyering.

Additional, Pt. 2: Tom Russell has a column on this case at the Huffington Post.

37 comments