Stonewall Jackson’s “Regiment of Free Negroes”

Within the smoke-and-mirrors, ignore-that-man-behind-the-curtain game that constitutes advocacy for black Confederate soldiers, one often comes across the claim that Stonewall Jackson commanded two battalions of African American troops. It pops up all over the place, including (briefly) in grade school textbooks in the Old Dominion. Remarkably, with 27 bazillion books published to date on the Civil War, and a fair number of those specifically about Ol’ Blue Light himself, no one’s ever bothered to name those two battalions by their official designation, identify their officers, or point them out on the order of battle for a specific engagement.

Within the smoke-and-mirrors, ignore-that-man-behind-the-curtain game that constitutes advocacy for black Confederate soldiers, one often comes across the claim that Stonewall Jackson commanded two battalions of African American troops. It pops up all over the place, including (briefly) in grade school textbooks in the Old Dominion. Remarkably, with 27 bazillion books published to date on the Civil War, and a fair number of those specifically about Ol’ Blue Light himself, no one’s ever bothered to name those two battalions by their official designation, identify their officers, or point them out on the order of battle for a specific engagement.

I’m not sure where the claim about these battalions originated, but it may be at least in part based on this news item from the front page of the Philadelphia Inquirer of November 27, 1861:

FROM THE UPPER POTOMAC POSITION OF THE REBELS — A FREE NEGRO REGIMENT A letter from Darnestown, Md., dated to-day, says. . . . Gen. JACKSON, who, as Colonel, formerly commanded at Harper’s Ferry, is engaged at Winchester in organizing, arming, and equipping a regiment of free negroes [sic.], said to number fully a thousand. The negroes are reported to be very enthusiastic in their new position.

Rumors and second-hand accounts of African American troops in Confederate service appeared frequently in Northern newspapers, especially during the early part of the war. We’ve seen how a single mention of black troops — from a source that seems dubious to start with — got rewritten and embellished and recycled, over and over, for weeks after the Battle of First Manassas. That one took in a lot of people, including (it seems likely) Frederick Douglass.

So now we’ve got a date (November 1861) and a location (Winchester, Virginia), for at least one (anonymous, second-hand) account of Jackson’s black troops. Anyone who has further details on this regiment — its commanding officer, its official designation, the actions in which it fought, or citations to it in Confederate sources, please drop it in the comments.

I have Fold3 open and waiting.

___________

Juneteenth, History and Tradition

[This post originally appeared here on June 19, 2010.]

“Emancipation” by Thomas Nast. Ohio State University.

![]()

Juneteenth has come again, and (quite rightly) the Galveston County Daily News, the paper that first published General Granger’s order that forms the basis for the holiday, has again called for the day to be recognized as a national holiday:

Those who are lobbying for a national holiday are not asking for a paid day off. They are asking for a commemorative day, like Flag Day on June 14 or Patriot Day on Sept. 11. All that would take is a presidential proclamation. Both the U.S. House and Senate have endorsed the idea. Why is a national celebration for an event that occurred in Galveston and originally affected only those in a single state such a good idea? Because Juneteenth has become a symbol of the end of slavery. No matter how much we may regret the tragedy of slavery and wish it weren’t a part of this nation’s story, it is. Denying the truth about the past is always unwise. For those who don’t know, Juneteenth started in Galveston. On Jan. 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. But the order was meaningless until it could be enforced. It wasn’t until June 19, 1865 — after the Confederacy had been defeated and Union troops landed in Galveston — that the slaves in Texas were told they were free. People all across the country get this story. That’s why Juneteenth celebrations have been growing all across the country. The celebration started in Galveston. But its significance has come to be understood far, far beyond the island, and far beyond Texas.

![]()

This is exactly right. Juneteenth is not just of relevance to African Americans or Texans, but for all who ascribe to the values of liberty and civic participation in this country. A victory for civil rights for any group is a victory for us all, and there is none bigger in this nation’s history than that transformation represented by Juneteenth.

But as widespread as Juneteenth celebrations have become — I was pleased and surprised, some years ago, to see Juneteenth celebration flyers pasted up in Minnesota — there’s an awful lot of confusion and misinformation about the specific events here, in Galveston, in June 1865 that gave birth to the holiday. The best published account of the period appears in Edward T. Cotham’s Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, from which much of what follows is abstracted.

The United States Customs House, Galveston.

![]()

On June 5, Captain B. F. Sands entered Galveston harbor with the Union naval vessels Cornubia and Preston. Sands went ashore with a detachment and raised the United States flag over the federal customs house for about half an hour. Sands made a few comments to the largely silent crowd, saying that he saw this event as the closing chapter of the rebellion, and assuring the local citizens that he had only worn a sidearm that day as a gesture of respect for the mayor of the city.

The 1857 Ostermann Building, site of General Granger’s headquarters, at the southwest corner of 22nd Street and Strand. Image via Galveston Historical Foundation.

![]()

A large number of Federal troops came ashore over the next two weeks, including detachments of the 76th Illinois Infantry. Union General Gordon Granger, newly-appointed as military governor for Texas, arrived on June 18, and established his headquarters in Ostermann Building (now gone) on the southwest corner of 22nd and Strand. The provost marshal, which acted largely as a military police force, set up in the Customs House. The next day, June 19, a Monday, Granger issued five general orders, establishing his authority over the rest of Texas and laying out the initial priorities of his administration. General Orders Nos. 1 and 2 asserted Granger’s authority over all Federal forces in Texas, and named the key department heads in his administration of the state for various responsibilities. General Order No. 4 voided all actions of the Texas government during the rebellion, and asserted Federal control over all public assets within the state. General Order No. 5 established the Army’s Quartermaster Department as sole authorized buyer for cotton, until such time as Treasury agents could arrive and take over those responsibilities.

It is General Order No. 3, however, that is remembered today. It was short and direct:

Headquarters, District of Texas

Galveston, Texas, June 19, 1865 General Orders, No. 3 The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere. By order of

Major-General Granger

F. W. Emery, Maj. & A.A.G.

![]()

What’s less clear is how this order was disseminated. It’s likely that printed copies were put up in public places. It was published on June 21 in the Galveston Daily News, but otherwise it is not known if it was ever given a formal, public and ceremonial reading. Although the symbolic significance of General Order No. 3 cannot be overstated, its main legal purpose was to reaffirm what was well-established and widely known throughout the South, that with the occupation of Federal forces came the emancipation of all slaves within the region now coming under Union control.

The James Moreau Brown residence, now known as Ashton Villa, at 24th & Broadway in Galveston. This site is well-established in recent local tradition as the site of the original Juneteenth proclamation, although direct evidence is lacking.

![]()

Local tradition has long held that General Granger took over James Moreau Brown’s home on Broadway, Ashton Villa, as a residence for himself and his staff. To my knowledge, there is no direct evidence for this. Along with this comes the tradition that the Ashton Villa was also the site where the Emancipation Proclamation was formally read out to the citizenry of Galveston. This belief has prevailed for many years, and is annually reinforced with events commemorating Juneteenth both at the site, and also citing the site. In years past, community groups have even staged “reenactments” of the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation from the second-floor balcony, something which must surely strain the limits of reasonable historical conjecture. As far as I know, the property’s operators, the Galveston Historical Foundation, have never taken an official stand on the interpretation that Juneteenth had its actual origins on the site. Although I myself have serious doubts about Ashton Villa having having any direct role in the original Juneteenth, I also appreciate that, as with the band playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee” as Titanic sank beneath the waves, arguing against this particular cherished belief is undoubtedly a losing battle.

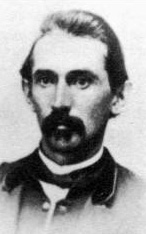

Assuming that either the Emancipation Proclamation (or alternately, Granger’s brief General Order No. 3) was formally, ceremonially read out to the populace, where did it happen? Charles Waldo Hayes, writing several years after the war, says General Order No. 3 was “issued from [Granger’s] headquarters,” but that sounds like a figurative description rather than a literal one. My bet would not be Ashton Villa, but one of two other sites downtown already mentioned: the Ostermann Building, where Granger’s headquarters was located and where the official business of the Federal occupation was done initially, or at the United States Customs House, which was the symbol of Federal property both in Galveston and the state as a whole, and (more important still) was the headquarters of Granger’s provost marshal, Lieutenant Colonel Rankin G. Laughlin (right, 1827-78) of the 94th Illinois Infantry. It’s easy to imagine Lt. Col. Laughlin dragging a crate out onto the sidewalk in front of the Customs House and barking out a brief, and somewhat perfunctory, read-through of all five of the general’s orders in quick succession. No flags, no bands, and probably not much of a crowd to witness the event. My personal suspicion is that, were we to travel back to June 1865 and witness the origin of this most remarkable and uniquely-American holiday, we’d find ourselves very disappointed in how the actual events played out at the time.

Assuming that either the Emancipation Proclamation (or alternately, Granger’s brief General Order No. 3) was formally, ceremonially read out to the populace, where did it happen? Charles Waldo Hayes, writing several years after the war, says General Order No. 3 was “issued from [Granger’s] headquarters,” but that sounds like a figurative description rather than a literal one. My bet would not be Ashton Villa, but one of two other sites downtown already mentioned: the Ostermann Building, where Granger’s headquarters was located and where the official business of the Federal occupation was done initially, or at the United States Customs House, which was the symbol of Federal property both in Galveston and the state as a whole, and (more important still) was the headquarters of Granger’s provost marshal, Lieutenant Colonel Rankin G. Laughlin (right, 1827-78) of the 94th Illinois Infantry. It’s easy to imagine Lt. Col. Laughlin dragging a crate out onto the sidewalk in front of the Customs House and barking out a brief, and somewhat perfunctory, read-through of all five of the general’s orders in quick succession. No flags, no bands, and probably not much of a crowd to witness the event. My personal suspicion is that, were we to travel back to June 1865 and witness the origin of this most remarkable and uniquely-American holiday, we’d find ourselves very disappointed in how the actual events played out at the time.

Maybe the Ashton Villa tradition is preferable, after all.

![]()

Update, June 19: Over at Our Special Artist, Michele Walfred takes a closer look at Nast’s illustration of emancipation.

![]()

Update 2, June 19: Via Keith Harris, it looks like retiring U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison supports a national Juneteenth holiday, too. Good for her.

______________

How — and Why — Real Confederates Endorsed Slave Pensions

In another forum recently, there was a lively discussion going on about the historical basis for present-day claims about black Confederates. One of the topics, naturally, was the pensions that some states awarded to African American men who had served as body servants, cooks, and in other roles as personal attendants to white soldiers. One person asked why it was that the former states of the Confederacy were so late in authorizing pensions for these men, or (in some cases) did not authorize them at all. It’s a good question, that I’m sure defies a single, simple answer.

But in the process of looking for something else, I came across this editorial in the October 1913 issue of the Confederate Veteran, calling on the states to provide pensions for a “a particular class of old slaves.” I’m putting it after the jump, because it’s peppered with racial slurs and stereotypes that are hurtful to modern ears, but were wholly unremarkable for that time, place and publication. So let me apologize in advance for the language, and hope that my readers will appreciate the necessity of repeating it here, in full and in proper context, in order to be crystal clear about the author’s meaning and intent. There are times when polite paraphrasing just doesn’t do the job.

As you read this editorial, keep in mind that the Confederate Veteran, by its own masthead, officially represented (1) the United Confederate Veterans, (2) the United Daughters of the Confederacy, (3) the Sons of Veterans (i.e., the SCV), and other groups. The magazine was mostly written by Confederate veterans and their families, to be read by Confederate veterans and their families. While the editorial may not reflect formal UCV/UDC/SCV policy, its appearance in the magazine does indicate that its perspective is one that would be shared by the magazine’s readership, and its call for action would reach a willing and receptive audience.

In short, if you want to know how real Confederate veterans viewed the purpose and necessity of pensions for former slaves, start here:

![]()

Confederate “Body Soldier” Honored with Fake Grave, Yankee Headstone

Update, June 12: The researcher behind the stone, Julia Barnes, pushes back hard against my piece below:

Update, June 12: The researcher behind the stone, Julia Barnes, pushes back hard against my piece below:

Andy, as with many issues, reporters make mistakes. The reporter did a good job and was trying to do a public service. The records for Wade Childs stated that he was a “body servant,” not “body soldier.” The burial site for both men, Lewis and Wade Childs, was the West View cemetery in Anderson. This is not supposition. It is based upon the death certificates. Both were buried in the same cemetery, by the same undertaker, about 12 months apart. This is not a fake grave. It is a placement based upon the records of the Anderson Cemetery records office, the South Carolina Vital Records department, and the Pension records found in the SC Archives, which noted his burial location and date. All of this was reviewed by the City attorney for approval of the placement of the headstone.

Fair enough. More in the comments.

_____________________

Even in the muddle of half-understood documents, vague definitions and simplistic, patriotic tropes one comes to expect of news stories about black Confederates, this one’s a mess:

Childs served as a body soldier with Orrs Regiment of the South Carolina Rifles in the Confederate army during the Civil War. He carried the belongings and camp supplies of white soldiers, one of some 20,000 to 50,000 slaves who labored during the war.

[Julia] Barnes believes he might also be one of the 3,000 to 10,000 black Confederates who Harvard researchers suspect fought for the South. The Southern army did not record black soldiers, said Barnes, an Anderson County historian.

I’ve never heard the term “body soldier” before, but I suspect I will again. It’s a modern obfuscation that both sounds substantive and conveniently elides the terms used 150 years ago. It’s not a term real Confederates would have understood or used. Childs would have been known as a “body servant,” or simply as a slave. There is a passing reference to Wade Childs’ being enslaved, but no reference to soldiers Private John Chiles or Captain James S. Cothran, to whom (according to his pension record) Childs was acting as servant. Childs labored for those men, not for the Confederate army. The headstone makes no reference to Childs’ role whatsoever. That’s almost unheard of on such stones, and suggests very strongly that the folks who put it up feel like the less said about that status, the better.

Mike Barnes, the local SCV camp commander, is quoted as saying that “they are considered veterans by the state of South Carolina,” but in fact the state viewed men like Childs very, very differently than it did rank-and-file Confederate soldiers. South Carolina first awarded pensions to disabled white veterans and their widows in 1887, and gradually expanded eligibility for other white veterans in the decades following. It was almost forty more years, though, before men like Childs were made eligible:

Act No. 63, 1923 S.C. Acts 107 allowed African Americans who had served at least six months as cooks, servants, or attendants to apply for a pension. Then in 1924, apparently because there were too many applications, the act was amended to eliminate all laborers, teamsters, and non-South Carolinians by extending eligibility only to South Carolina residents who had served the state for at least six months as “body servants or male camp cooks.”

The evidence for Child’s involvement with the Confederate military seems to rest entirely on his 1923 pension application (read it here), which is fine as far as it goes. (See another example of the limits of Confederate pension records here.) But the pension application is very clear about what Childs’ (or Chiles’, as it’s given in the application) role was during the war as a servant — none of this vague “body soldier” business mentioned there.

It’s also important to note that, as is often the case with such applications, the case for Childs’ worthiness for such a pension was made not only on his wartime service to his master, but also on his continued adherence to the racial status quo antebellum in the South. “Wade has been a faithful, dependable negro [sic.],” his primary sponsor writes, “humble to white people and always willing to serve them.” Contrary to the assertions of the local SCV camp commander, this is hardly a case of Childs’ service being recognized by the state as being anything like that of white veterans, armed and in the ranks.

Make note also of the fact that, as of 1924, African Americans who had worked as laborers and teamsters, men whose activities were arguably more directly beneficial to the South’s military effort, were explicitly excluded from the pension program in favor of those men like Childs who had served individual white soldiers. Cooks and personal servants counted; the men who built earthworks and drove wagons did not. That was the policy of the state of South Carolina.

All of this is par for the course in “honoring” black Confederates, but there’s an additional element here that adds another layer of dubious research findings:

Barnes and her husband discovered that Childs’ brother Lewis was buried at Westview, a historically black cemetery. They concluded that Wade Childs must be buried there, too.

Westview’s military corner facing Reed Street is “wall-to-wall” with unmarked graves, Barnes said.

“I had been looking and found his brother there,” Barnes said. “It’s logical that he would be there since his brother is there. We don’t know where, but when we saw Lewis, we felt his was there, too.”

Yes, you read that right — they have no damn idea where Wade Childs is actually buried. They’re guessing, and placed a stone in that cemetery, on that spot, because they “felt” that was the spot, that it was “logical” to them. It’s a fake grave, just like the ones in Pulaski — with the exception that the folks in Tennessee at least added fine print noting that location of the person mentioned is unknown. No such truth-telling here.

To add an extra bit of irony, these noble defenders of Southron Honour™ put up a stone with a rounded top, like those of of U.S. veterans, not the peaked top usually used for former Confederates. How on earth did they get that one wrong?

I dare say these folks found a local African American man in the South Carolina pension rolls, and ended up so determined to commemorate their very own black Confederate that little details like, oh, actually knowing where he’s buried became irrelevant to putting up a marker and chalking up another “forgotten segment of South Carolina’s past.” Thank goodness these folks are only promoting heritage — if they called this half-baked foolishness history, they’d be laughed out of town.

______________

Update, May 31: I originally put this down in the comments, but it might be useful to explain further why I’m a bit exercised about this “fake grave” business, an action that I (still) consider to be so misleading as to border on willful dishonesty.

Long-time readers may recall my post just about exactly a year ago on Peter Phelps, a white Confederate soldier who’d been named as a “black Confederate” by another website. In researching Peter Phelps, I found documentation not only of the cemetery he was buried in, but also the section. Unfortunately, there is no marker there now to identify the exact spot, so I posted a photo of the area with a caption that it showed the area where he was buried, but the precise location is not known. That’s fair, that’s accurate, and that’s honest. What I did not do is take a picture of an empty patch of soil and state, “this is Peter Phelps’ grave,” which is essentially what the Barnes are doing with Wade Childs.

As for their assumption that Wade Childs is buried next to his brother, the Phelps case is also instructive. Peter’s wife, Lucinda, died several years before he did, and we know (again from interment records) that she was buried in a plot in the same part of that cemetery. But section and plot numbers also make it clear that they are not buried together, as one might assume a married couple would be. While it may seem “logical” to think that Childs is buried near his brother, in the absence of actual evidence of that, it seems foolhardy to me to make that assumption and set it in stone (literally) for future generations. Visitors to that South Carolina cemetery a week from now, a year from now, fifty years from now, are going to be left with the belief that they saw the grave of Wade Childs, when in fact they might not have been within fifty (or a hundred) yards of it. Does that sort of precision really matter? Yes, I think it does, especially when it involves placing a marker that’s intended to last for generations to come.

As I’ve said, there are many ways to recognize a person, or a burial, without setting up a fake grave. It can be done. Even the faux cemetery for black Confederates at Pulaski, which is disingenuous and misleading in so many ways, acknowledges that the men so “honored” do not actually lie under those stones.

For those who want to engage in the heritage vs. history debate, this commemoration of Wade Childs offers lots to chew on. It’s a great example of the difference between two different approaches. Serious historians know the limits of their knowledge of a subject, and are willing to say “we don’t know that; we don’t actually know where Wade Childs is buried.” A serious historian does not go around setting up a simulated gravesite as a means of “honoring” a deceased person, or making up a term like “body soldier” to muddy the waters around the man’s actual role in the war, while ignoring critical elements of the primary, documentary record that undermine the chosen narrative. “Heritage” advocates do that sort of thing all the time, and aren’t even aware they’re doing it, or understand that it’s a problem.

So by all means, “forward the Colours,” y’all. Just don’t think what you’re doing counts as history.

______________

Image: Jennifer Crossley Howard, IndependentMail.com.

“. . . to be divided between Robert Smalls and his associates.”

“Prize money” is a concept very familiar to maritime history buffs, or those who’ve read a lot of Forester or O’Brian. The idea was simply to provide a monetary incentive to naval personnel not just to destroy, but to capture intact, enemy vessels that could be either used as warships by their captors, or sold at auction to private owners. (Several ACW blockade runners went through this cycle several times.) A captured ship would be put through a legal proceeding — a “prize court” — and if “condemned,” it would be sold and (after deductions for expenses related to the appraisal, court costs and sale), the proceeds divided up among the crew of ships participating in the seizure of the vessel. The lion’s share of the money would be shared by the captain and officers of the capturing ship, on the assumption that they were more responsible for the capture than individual sailors; a successful cruise might set up a lucky naval captain for life, financially, while a sailor or ordinary seaman would collect enough for a wild evening of eating, drinking, and other, uh, forms of shoreside entertainment.

Prize money isn’t mentioned much in popular accounts of the ACW at sea, but it was nonetheless an important element in the minds of sailors in the Union blockading squadrons at the time. The Federals used a relatively complex formula at the time for apportioning prize money. After deductions for expenses, one-half of the money went straight to the government. Five percent went to the commander of the regional blockading squadron (in this case, the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron), and a further 1% went to the local squadron commander. These shares combine to account for 56% of the value of the prize.

The remaining 44% was divided among the officers and crew of the capturing vessel(s). This amount was split into 20 equal shares, with the captain taking 3 shares, the officers and midshipmen taking 10 shares, and the enlisted men dividing up the remaining 7 shares between them.[1] Clear as mud, right? Here’s a made-up example to show how it worked:

Say a Union gunboat off Charleston, U.S.S. Hypothetical, captured a Confederate ship. Hypothetical has 1 captain, 10 officers and snotties, and 70 enlisted men in her crew. After deductions for the adjudication of the prize, the captured Confederate ship has a value of $10,000. With me so far? Here’s how that scenario would break out in terms of prize monies:

![]()

![]()

You can see immediately that a lucky and industrious ship’s captain could amass a substantial amount of money quickly, and a senior admiral on a prize-rich station – say, the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, off Cape Fear and Wilmington, North Carolina – could become wealthy indeed. The disparity of prize money distribution between the senior officers and ordinary seamen (who, after all, were exposed to most of the same risks) was a perennial complaint around mess tables in navies on both sides of the Atlantic:

![]() ‘

‘

A British cartoon from the time of the Napoleonic Wars. The officer asks the praying sailor if he’s afraid of the enemy. “Afraid? No!,” the sailor replies, “I was only praying that the enemy’s shot may be distributed in the same proportion as the prize money, the greatest part among the officers!”

![]()

Anyway, that’s how prize money was supposed to work in the Union navy during the Civil War. The case of Planter and her makeshift crew, though, had some unusual wrinkles. First, the Confederate steamer was not really captured in action, but rather simply ran out to the nearest Union warship (in this case, U.S.S. Onward), and surrendered. More important, Planter’s makeshift crew were not U.S. naval personnel, and so not eligible for prize money under normal circumstances. Samuel F. Du Pont (left, 1803-65), the flag officer commanding the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, wasn’t sure how to handle the question of prize money in this case, but passed the question along to Washington. “I do not know whether. . . the vessel will be considered a prize,” Du Pont wrote in his report of the incident to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, “but, if so, I respectfully submit to the Department the claims of this man Robert [Smalls] and his associates.”[2]

Anyway, that’s how prize money was supposed to work in the Union navy during the Civil War. The case of Planter and her makeshift crew, though, had some unusual wrinkles. First, the Confederate steamer was not really captured in action, but rather simply ran out to the nearest Union warship (in this case, U.S.S. Onward), and surrendered. More important, Planter’s makeshift crew were not U.S. naval personnel, and so not eligible for prize money under normal circumstances. Samuel F. Du Pont (left, 1803-65), the flag officer commanding the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, wasn’t sure how to handle the question of prize money in this case, but passed the question along to Washington. “I do not know whether. . . the vessel will be considered a prize,” Du Pont wrote in his report of the incident to Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, “but, if so, I respectfully submit to the Department the claims of this man Robert [Smalls] and his associates.”[2]

Welles may or may not have sorted out the legal complexities of the case for himself, but he hardly had time to consider it regardless. On May 19, 1862 – just six days after Planter’s daring run out of Charleston — Senator James W. Grimes of Iowa (right, 1816-72), a member of the Naval Committee, introduced legislation authorizing the Welles to have the steamer and its gear appraised, and half the values awarded to “Robert Small [sic.] and his associates who assisted in rescuing [Planter] from the enemies of the Government.” The legislation further instructed Welles to, at his discretion, invest the monies in U.S. securities and pay Smalls and his companions the interest “annually until such time as the Secretary of the Navy may deem it expedient to pay him or his heirs the principal sum.” In the House of Representatives, the Senate bill was held up briefly on procedural grounds by the infamous Copperhead, Clement Vallandigham of Ohio, but it passed a week later on May 26, 1862, by a vote of 121 to 9, with Vallandigham in the latter group. The bill was formally enrolled the next day, and signed by the president on May 30, just over two weeks after Smalls’ escape.[3] The full act read:

Welles may or may not have sorted out the legal complexities of the case for himself, but he hardly had time to consider it regardless. On May 19, 1862 – just six days after Planter’s daring run out of Charleston — Senator James W. Grimes of Iowa (right, 1816-72), a member of the Naval Committee, introduced legislation authorizing the Welles to have the steamer and its gear appraised, and half the values awarded to “Robert Small [sic.] and his associates who assisted in rescuing [Planter] from the enemies of the Government.” The legislation further instructed Welles to, at his discretion, invest the monies in U.S. securities and pay Smalls and his companions the interest “annually until such time as the Secretary of the Navy may deem it expedient to pay him or his heirs the principal sum.” In the House of Representatives, the Senate bill was held up briefly on procedural grounds by the infamous Copperhead, Clement Vallandigham of Ohio, but it passed a week later on May 26, 1862, by a vote of 121 to 9, with Vallandigham in the latter group. The bill was formally enrolled the next day, and signed by the president on May 30, just over two weeks after Smalls’ escape.[3] The full act read:

![]()

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the Secretary of the Navy be, and he is hereby, authorized to cause the steam transport boat Planter, recently in the rebel service in the harbor of Charleston, and all of the arms, munitions, tackle, and other property on board of her at the time of her delivery to the Federal authorities, to be appraised by a board of competent officers, and when the value thereof shall be thus ascertained to cause an equitable apportionment of one-half of such value so ascertained as aforesaid to be made between Robert Small[s] and his associates who assisted in rescuing her from the enemies of the Government. Section 2. And be it further enacted, That the Secretary of the Navy may, if he deems it expedient, cause the sum of money allotted to each individual under the preceding section of this act to be invested in United States securities for the benefit of such individual, the interest to be paid to him or to his heirs annually until such time as the Secretary of the Navy may deem it expedient to pay to him or his heirs the principal sum as aforesaid.

![]()

The provision for Planter’s prize monies to be invested in securities and held indefinitely at the discretion of the Secretary of the Navy is, as far as I know, virtually unknown when it comes to regular U.S. naval personnel. To be sure, as with anything associated with governmental bureaucracy and accounting, delays, lost paperwork, and missing approvals were routine, and it was common for seamen and officers to wait many months, or even years, to receive the prize monies they’d earned during the war. (I once researched a case in which a Union officer’s claim against a civilian ship went all the way up to the Supreme Court, where he lost in late 1867. Or rather, his estate lost; the officer himself had died more than two years before.) But once prize money was cleared to be awarded, it was distributed. There’s little doubt that this case was handled as it was because the recipients were African Americans, former slaves, who were assumed to be unable to trusted to handle large sums of money wisely. It was well-intentioned, but patronizing and ultimately an insulting rationalization that kept Robert Smalls and his crew from receiving direct compensation for their actions for a long time, if ever.

Welles forwarded the text of the new legislation to Flag Officer Du Pont on June 6, along with instructions to have the captured steamboat appraised.[4] In due course, Planter was inspected and assessed to be worth $9,000; the four loose guns, intended by the Confederates for the new battery being built on pilings in the middle of Charleston Harbor, were valued at an additional $168, for a total of $9,168. That number is strikingly low for a nearly-new steamboat in good operating condition, loaded with munitions; I may discuss that in another post. Regardless, under the legislation passed in May 1862, Smalls and his crew were entitled to half that amount, or $4,584. Du Pont ultimately divided the monies as follows:

![]()

![]()

How much was their prize money worth, in modern terms? An historical economist might say, “quite a bit” or “a lot.” In fact, there’s no single, direct answer to that question. There are a variety of formulae and indices used by economists to track the value of currency over time, and they give widely (and wildly) different results. Even in a single category, tracking income and wealth, the modern equivalent of the prize money awarded the crew of Planter varies between a low of around $106,000 to as high as $12M. The equivalent using unskilled labor as a basis of comparison pegs the modern equivalent at around $737,000, which seems very roughly in the ballpark to me.

Did Robert Smalls, William Morrison and the others ever see any of the principal of the money they’d been awarded by Congress? I’d like to say they eventually did, but if fact I don’t know. For certain, there would be plenty of people, in government and out, to whom the idea of turning over a large sum of money to freedmen and –women would be an anathema, and there were plenty of ways for them to rationalize cheating Smalls and the others of their hard-earned reward. (Think about the corrupt recruit depot quartermaster in the film Glory.) I hope they did eventually receive their prize money, along with the interest it had accrued.

[1] Rodman L. Underwood, Waters of Discord: The Union Blockade of Texas During the Civil War (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2003), 35.

[2] S. F. Du Pont to Gideon Welles, “Abduction of the Confederate steamer Planter from Charleston, S. C., May 13, 1862.” May 14, 1862. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies, Series I, Vol. 12, 821.

[3] Congressional Globe, Senate, 37th Congress, 2nd Session, May 19, 1862, 2186-87; ibid., 2363; ibid., 2392; Statutes at Large, 37th Congress, 2nd Session, 904.

[4] Gideon Welles to S. F. Du Pont, “Letter from the Secretary of the Navy to Flag-Officer Du Pont, U. S. Navy, transmitting copy of an act of Congress in the case of Robert Smalls and others.” ORN, Series I, Vol. 12, 823.

____________

Images: Top, escape of the steamer Planter by R. G. Skerrett, from the ORN. Images of Planter’s crew adapted from “Heroes in Ebony–The captors of the Rebel steamer Planter, Robert Small, W. Morrison, A. Gradine and John Small,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 21m 1862, via Library of Congress. Gridiron’s name is given elsewhere as “Gradine”; I’ve adopted the spelling used in official naval correspondence.

The Black Confederate Who Stole the Steamboat Planter

In my post about Robert Smalls and the “abduction” of the Confederate steamer Planter the other day, I overlooked the last two grafs of the Harper’s Weekly story which, line-for-line, may be the most interesting of the piece:

Our correspondent sends us a drawing of an infernal machine [i.e., a mine], drawn by one of the negro hands of the Planter named Morrison. This chattel, Morrison, gives the following account of himself:

Belonged to Emile Poinchignon [Poincignen]; by trade a tinsmith and plumber; has lived all his life in Charleston; was drum-major of the first regiment of the Fourth Brigade South Carolina Militia, and paraded on the 25th of last month; has a wife and two children in Montgomery, Alabama, whom he expects to see when the war is over. I asked him how he learned to read and write. Answer: “I stole it in the night, Sir.”

Okay, okay. Calling William Morrison a “black Confederate” seems pretty silly under the circumstances. But William Morrison must, in some ways, capture all the complexities of of the situation of many African American men in the Confederacy during the war. Through his trade as a craftsman, Morrison probably enjoyed better circumstances than the majority of enslaved persons in the South, but he remained bound by the system. He suffered from a long, distant absence from his wife and children — no doubt an involuntary one. He learned to read and write not through the efforts of a kind and paternal master, but secretly, though his own initiative — “I stole it in the night.” And when he saw the opportunity to steal himself from his master, he didn’t just run off, but did so in a way that would cause the largest possible damage and embarrassment on the Confederacy, in a way that would (not coincidentally) assure his own death if recaptured. And finally, when he did reach the Federal blockading fleet, he shared with them intelligence about Charleston’s harbor defenses: a mine that, by virtue of his skills as a tinsmith and plumber, he may have actually helped assemble with his own hands.

William Morrison was neither a “happy Negro,” nor a “faithful slave.” Next time someone points to a vague reference to an African American musician or otherwise connected to the Confederate military, and then waxes eloquent about that as evidence of black Confederates fighting for home and hearth against the Yankee invader, etc., etc., ask them about William Morrison of the steamboat Planter.

________________Image: Detail of the print, “Heroes in Ebony — The captors of the Rebel steamer Planter, Robert Small, W. Morrison, A. Gradine and John Small.” Library of Congress.

“Disgusting treachery and negligence”

Today is the sesquicentennial of one of the most audacious acts of the Civil War, when Robert Smalls, an enslaved African American trained as a harbor pilot, took his vessel out the Union blockading fleet off Charleston. It’s already been mentioned several places, with due credit to Smalls and his comrades. As Union Admiral David Dixon Porter put it in his naval history of the war, “this required the greatest heroism, for had he been caught while leaving the wharf, or stopped by the forts, he would have paid the penalty with his life.” More on Smalls and Charleston here.

So given the coverage Smalls’ actions will get — and rightly so — I thought it would be interesting to see the coverage from the other side, from the perspective of Confederate Charleston. Here, from the Charleston Mercury, May 14, 1862:

DISGUSTING TREACHERY AND NEGLIGENCE Yesterday, at daylight, the steamer Planter, in the absence of her officers, was taken by four or five of her colored crew from her berth at Southern Wharf, to the enemy’s fleet. She is a high pressure cotton boat, of light draught, formerly plying on the Pee Dee River, but latterly chartered by the Government, with her officers and crew, from Mr. Ferguson, her owner, and used as a transport and guard boat about the harbor of Charleston. Her armament was a 32-pounder and a 24-pound howitzer. The evening previous she had taken aboard four guns for one of the newly erected works, either that on Morris Island or Fort Timber, viz., a 42-pounder rifled and banded, an 8-inch columbiad, both of which had been struck at the reduction of Ft. Sumter, and 8-inch seacoast howitzer, and a 32-pounder. These guns were to have gone to their destinations early in the morning, and been mounted yesterday. Three sentinels were stationed in sight of her, and a detail of twenty men were within hail for the relief of the post. Between half-past three and four o’clock the Planter steamed up and cast loose, the sentinels having no suspicion of foul play, and thinking she was going about her business. At quarter past four o’clock she passed Fort Sumter, blowing her whistle, and plainly seen. She was reported by the Corporal of the Guard as the guard boat, to the Officer of the Day, Captain Flemming, one of the best and most reliable officers of the garrison. The fort is only called on to recognize authorized boats passing, taking for granted that they have their officers aboard. This was done as usual. The run to Morris Island goes a long way out past the fort, and then turns. The Planter on this trip did not turn. The officers of the Planter were [Charles J.] Relyea, Captain; Smith, Mate; and Pitcher, Engineer. They have been arrested, and will, we learn, be tried by court-martial for disobedience of a standing general order, that the officers and crews of all light draught steamers in the employment of the Government will remain on board day and night. The result of this negligence may be only the loss of the guns and of the boat, desirable for transportation. But things of this kind are sometimes of incalculable injury. The lives and property of this whole community are at stake, and might be jeopardized by event apparently as trifling as this. It ism therefore, due to the Service and to the Cause, that this breach of discipline, however innocent in intention on the part of the officers, should be dealt with as it deserves. Without strict discipline, no military operations can succeed.

Note that the black men who stole the boat get only a passing mention; virtually the entire piece focuses on the incompetence and negligence on the part of Confederate authorities in letting them get away with it. There’s no surprise expressed that Smalls and his companions would attempt to take the boat, so much as shock that they were able to pull it off. The newspaper story makes no hint of a betrayed assumption of loyalty on the part Planter‘s enslaved crew members to either their owners, or to the Confederate cause.

The newspaper got the name of the ship’s mate wrong; he was not “Smith,” but John Smith Hancock. He, Engineer S. Z. Pitcher, and Captain Relyea, went to trial; Relyea and Hancock were both found guilty. Relyea was sentenced to three months’ imprisonment and a $500 fine, which if he did not pay would be commuted into a sentence of two additional months. Hancock was sentenced to one month in prison and a $100 fine. Engineer Pitcher argued “in bar of trial” that the charges were vague and insufficient, and after careful deliberation the charges against him were voided.

In his review of the court martial, however, Major General John C. Pemberton, commanding the Confederate Department of South Carolina and Georgia, overturned the convictions of Relyea and Hancock, noting that Planter‘s owner, Ferguson, “seems to have been entirely deficient as to the deportment of his subordinates.” Pemberton found that while Relyea and Hancock were in violation of general orders, “it is not clearly shown that General Order No. 5, referred to in the specification of the charges, had ever been properly communicated to Captain Relyea, or Hancock, the mate, nor do any measures appear to have been taken by their superiors to force an habitual compliance with the requirements of those orders” (Charleston Mercury, August 1, 1862). Relyea and Hancock were released.

I’ve read online that Captain Relyea was lost at sea between Charleston and Nassau in 1864, suggesting that he got involved in blockade running. Not sure if that’s true, but he left behind a spectacular, gold-headed cane of his that was sold twice last year at auction.

_______________

LoS President: Democracy Only Works When White Folks Run Things

You’ve got to appreciate the candor of J. Michael Hill, founder, president, and self-described “big chief” of the League of the South; he leaves no one in doubt about what really matters to him:

Majority rule only works where there is already a consensus of sorts on the fundamental issues within a particular society. For instance, in a Christian nation that enjoys a high degree of homogeneity in its racial and ethnic make-up, language, institutions, and inherited culture, most matters up for a vote are largely superficial policy issues. They don’t tamper with the agreed-upon foundations of the society. However, in a multicultural and multiracial polyglot Empire such as ours is today, the concept of majority rule is often fraught with dire (and even deadly) consequences for the losers, especially if the winners bear a grudge. As I write in 2012, there are projections that these United States—and our beloved Southland–will have a white minority by 2040 (or before, depending on immigration policy). Simply put, that will mean the end of society as we know it. You and Bill Clinton may be OK with this, but I’m not. Who stands to lose by this devil’s bargain? The descendants of America’s founding stock will be the losers. As a native white Southerner, I’m primarily concerned about the future of the South. Our ancestors bequeathed us a republican society based on Christian moral principles, the English language, racial (and some degree of ethnic) homogeneity, and British legal and political institutions. All this will be gone with the wind if we don’t stand as united white Southerners against the unholy leftist trinity of “tolerance, diversity, and multiculturalism.”

![]()

To be sure, this line of argument is nothing new coming from Hill; this essay dates back to 2007 (at least), with only a few slight edits. It’s not a gaffe, a one-off, but rather suggestive of a thought-out, stable perspective on Hill’s part. It’s policy, and an idea he’s expressed before:

We are already at war—we just don’t know it. One instance: Immigration. This is not just a matter of policy. It’s a matter of our very survival as white men and women of European Christian stock on this land we call the South. It is a zero sum game—we win or they win. There is no middle ground for compromise. Losing means that my grandchildren will grow up in a third world country. Multiculturalism and diversity means “we” cease to exist as a viable and prosperous people.

You have to wonder what Hill sees as the role and voice for African Americans and others is in his vision of an independent South is; some of those folks undoubtedly have families that trace back as far as Hill’s does, regardless of how they came to be there. (And note, as Will Rogers used to say, “some of them were there to meet the boat.”) What is their voice, their political agency in the “Free South” Hill and the League of the South envision? Sure, there will always be a place for highly-paid entertainers, fluffing people like Hill and assuring them how grateful black folks ought to be for helping them when the Supreme Court forced Jim Crow on the South, but what about everybody else?

Honesty can be invigorating, even when it’s unpleasant — like getting a cold bucket of water dumped on you. For all the discussion of abstract concepts like liberty and freedom, Hill’s core concern is, explicitly, about maintaining and preserving white power — political, cultural and social. His candor should be welcomed; it’s always good to know exactly where he and the League of the South stand, and what they stand for.

_______________

HMNS Lecture Monday, “They Fought Like Tigers: Skirmish at Island Mound”

A quick reminder that tomorrow evening, Monday, at 6:30, the Houston Museum of Natural Science will present another in its lecture series in conjunction with the Discovering the Civil War exhibition. Historian Chris Tabor will present “They Fought Like Tigers: Skirmish at Island Mound.” From the museum website:

The action fought by the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteers on October 29, 1862, marked the first time that an African-American regiment experienced combat during the Civil War. No quarter was asked and none given by either side during the fight, which involved brutal hand-to-hand combat. A veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps, Chris Tabor has focused his research on the particularly brutal warfare that raged in Western Missouri. He authored The Skirmish at Island Mound which provides the first ever detailed research into the first battle fought by African American soldiers during the Civil War.

_________

Radical Reconstruction, Insurgencies, and the Concept of Dau Tranh

Atlantic commenter XinJeisan flags an interview with Ohio State University historian Mark Grimsley, conducted by Mike Few for the Small Wars Journal. It’s an interesting piece, because it effectively summarizes the course of Reconstruction in the former Confederacy, and also because it puts that struggle over political power in the context of other insurgencies in world history. Here, Grimsley argues that the level of violence in the South, while low compared to the wholesale slaughter that preceded it, was nonetheless one that today would be considered a war:

A more clunky response, since you mention social scientists, would be to point to the Correlates of War Study, which defines a war as any event that results in a thousand or more battlefield deaths each year. If you substitute “deaths from political violence” for “battlefield deaths,” then several years during Reconstruction would come close to meeting this standard. In Louisiana alone, for example, an estimated 2,500 people perished between 1865 and 1876.

My own state, Texas, provides another example. Grimsley notes that a disproportionate number of Federal troops posted in the old Confederacy during Reconstruction were in Texas, in part to guard the border with Mexico. Nonetheless, violence against African Americans and whites believed to be aligned with the Reconstruction government was commonplace. Even officers of the Freedmen’s Bureau were targets. I blogged recently about NARA’s “Discovering the Civil War” exhibition, currently at the Houston Museum of Natural Science, and the inclusion of a bound volume of incidents recorded by Freedmen’s Bureau officers, “Criminal Offenses Committed in the State of Texas, 1865-68.” According to the companion book to the exhibition, the three volumes of the set record some 2,000 separate incidents of white-on-black violence between September 1865 and December 1868, ranging in scope from simple assault to torture to murder. Many are clearly linked to the economic and social turbulence of Reconstruction — several incidents on this page are noted as being brought about by a dispute over wages, for example, while other cases are less clear — but there is no avoiding the conclusion that African Americans were common targets of violence during the period.

One page from the “Criminal Offenses Committed in the State of Texas, 1865-68,” listing reported attacks in September and October 1866. The descriptions of incidents (column 6) include “kicking a woman,” “assault & battery,” “beating woman with quirt on head, face & shoulders,” “cutting with a hatchet,” “shooting,” “fracturing skull” and “homicide.” Three of the twelve victims were women; all but one were black (column 8). All of the alleged perpetrators (column 5) were white. From the companion volume to “Discovering the Civil War.”

Grimsley continues, arguing that white Southerners’ efforts to reclaim power through violence and intimidation was mainly the work of local groups, and that the Klan was more akin to a brand than a top-down, operational structure:

Southern whites never created an insurgency in the Maoist sense of a centrally directed people’s war. The Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan was a myth. What you had instead was a complex insurgency of local groups who conducted terrorist campaigns of intimidation and assassination. These efforts were uncoordinated but had the effect of undermining the Republican state governments.

Some of these groups operated under the guise of the Ku Klux Klan, but in most instances the Klansmen were effective only in curtailing attempts by African American families to assert some degree of economic independence. Only in South Carolina did the Klan become a major threat to the state government. The largest and best organized of these groups were the White Leagues in Louisiana, the Rifle Clubs in Mississippi, and the Redshirts in South Carolina. The latter two succeeded in “redeeming” their respective states. The first came close to doing so, and would have succeeded had the U.S. government rendered their efforts unnecessary, by abandoning Reconstruction and simply handing them Home Rule.

It’s important to understand that, in saying “the Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan was a myth,” Grimsley’s making a point about the Klan as a unified command structure. Even though the Klan had a national leadership for purposes of recruitment and communication, the individual dens, as they were known, were largely autonomous. And even they comprised only part of the many groups that sprang up across the South to oppose and undermine the process of Reconstruction.

Finally, Grimsley pulls back to look at white Southerners’ response to Radical Reconstruction — terrorism, voter intimidation, political machinations — as part of a unified whole that, in concept, is not at all unique to the American historical experience:

The pattern of the Reconstruction insurgency closely corresponds with dau tranh, a Vietnamese term that literally means “the struggle” but has a much richer connotation. Dau tranh rejects the idea that insurgency should be confined to guerrilla warfare. Instead it prescribes the exploitation of any and all means to achieve the desired objective. If given access to the political process by the targeted government—as occurred during Reconstruction—an insurgency following the tenets of dau tranh does not accept the legitimacy of that process (as the targeted government hopes it will), but simply regards such access as an additional tool by which to undermine and overthrow the government. Dau tranh employs social measures (in the context of Reconstruction, the ostracism of white southerners who supported or tolerated the Republican order), economic measures (the discharge of black laborers and boycotts aimed at uncooperative white merchants and planters), agitation and propaganda (the Democratic press), and paramilitary measures (intimidation and violence). As one of its foremost interpreters has explained, “the basic objective in dau tranh strategy is to put armed conflict into the context of political dissidence. Thus, while armed and political dau tranh may designate separate clusters of activities, conceptually they cannot be separated. Dau tranh is a seamless web.”

It’s telling that dau tranh (or đấu tranh) has the same meaning as jihad in Arabic — “the struggle.” In Arabic, jihad has a wider meaning that’s not limited to violent conflict, as it is commonly misunderstood in the West. Further, Grimsley’s characterization of the Reconstruction-era Klan — “a complex insurgency of local groups who conducted terrorist campaigns of intimidation and assassination. . . operated under the guise of the Ku Klux Klan” — is not unlike a description of al Qaeda, Arabic for “the base.” Al Qaeda is a very real, and still very dangerous organization, but much of the violence committed in its name, particularly in the Middle East, is done by small groups acting on their own, with little or no involvement by the larger organization. The horrific London bombings in 2005 were inspired by al Qaeda and violent Islamist rhetoric, but the conception, planning and execution of the attack were carried out by terrorists acting on their own initiative within the United Kingdom. International inspiration, but local action. Take Grimsley’s quote from earlier in this paragraph (“a complex insurgency of local groups. . .”), swap out the name of the Klan for al Qaeda, and you’ve got a fair description of the organizational structure of international terrorism over the last decade.

I don’t want to overstate this narrow analogy between modern, Islamist terrorism and the Reconstruction-era violence in the former Confederacy. But Grimsley’s observations are enlightening when it comes to viewing white Southerners’ efforts to push back against Radical Reconstruction. Political agitation, intimidation, violence and murder were all used, in concert and in parallel, to restore something akin to the status quo antebellum. In that sense, it’s remarkable how much the insurgency of white Southerners against the policies and supporters of Reconstruction resembles insurgencies elsewhere. As Mark Twain purportedly said, history doesn’t actually repeat itself, but sometimes it does rhyme.

__________Image: Thomas Nast’s depiction of the driving forces behind the Democratic candidate in the 1868 presidential election, Horatio Seymour. The standing figures are (from left) a caricatured, cudgel-wielding Irish Catholic immigrant street tough, symbolizing the violence of the New York City Draft Riots of 1863; Nathan Bedford Forrest, brandishing a knife labeled “the Lost Cause” and a lapel badge inscribed “Fort Pillow”; and August Belmont, a Manhattan financier who’s shown waving a packet of money marked “Capital for Votes.” All three stand on the body of an African American man, a former Union soldier. Image via HarpWeek.com, which also has more detail on the image.

24 comments