How to Make a Black Confederate from Nothing at All

Mary Johnson, granddaughter of Pvt. Samuel Brown, holds an American flag presented to her at the event. Paul Chinn/SF Chronicle

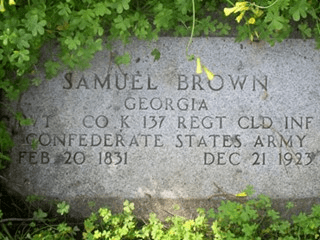

Over the weekend, David Woodbury of Battlefields and Bibliophiles and Kevin Levin at Civil War Memory highlighted a story in the San Fransisco Chronicle, about Samuel Brown, an African American Civil War veteran whose grave in Vallejo, California, was recently marked with a stone commemorating his service with the 137th United States Colored Troops. The event came about because the original stone, which had been on Brown’s gravesite since shortly after his death, designated him as a Confederate veteran. Via the CBS teevee affiliate in San Fransisco, Brown’s grave had originally been marked with a stone that read, contradictorily,

So it was a fnckup at the engravers, simple as that. Someone assumed that a Civil War soldier from Georgia must’ve been a Confederate. Nothing nefarious or conspiratorial. Mistakes like this are unfortunate, but certainly not unheard of. Read the full article here.

What’s most remarkable about this story, though, is not the story itself, but the reaction to it. Corey Meyer, posting at Blood of My Kindred, asks, “is this how Black Confederates are created?”

Why yes, Corey. Yes it is.

As Corey points out, the comments section of the original story is already filling with posters who, based on nothing at all, are accusing the ceremony’s organizers with changing Pvt. Brown’s history to conform to modern-day political correctness, and to cover up the fact that Brown was really a Confederate soldier. Commenter levesque writes, “my uninformed guess is that Mr. Brown was a black Confederate soldier who surrendered to occupying Union Army forces in Georgia.” He continues, “As anyone who has seen Gone With the Wind knows. . . .”

An “uninformed guess,” based on watching Gone with the Wind. There’s some scholarship. Watch out, Blight, you effete liberal hack, levesque is gunnin’ for your endowed chair.

Someone calling him- or herself whiteheat uses Brown as a jumping-off point for a Beckian rant about Lincoln and how he started the long, slow destruction of Real America™:

What this article does not mention is that many African slaves did indeed fight for the Confederacy. Lincoln’s ‘Emancipation Proclamation’ was issued two years into the civil war, and was mostly for propaganda purposes, since Lincoln said repeatedly that he would be willing to retain slavery if it would preserve the Union. Lincoln was all about Federal power and Big government. He also believed that whites and “negros” could not live together as equals.

After presiding over America’s most destructive war (quite a feat) Lincoln’s additional legacy is that he got us lurching towards Empire. America’s decline can (in part) be attributed to this magnificent war-maker.

Yet another commenter, blogorama, brings the snark:

How is this a positive story? For almost 100 years this man was laid to rest under a head stone that identified him as an ignorant buffoon instead of a hero. And his family never noticed. Gee, that’s heart warming.

Enfield53 — get it? — also jumps to the defense of the idea of Black Confederates, saying

Thousands of slaves and free blacks did serve with honor in the Confederate Army. Indeed, twenty percent of the Confederate Navy was black as well. There are hundreds of photographs taken of black Confederates taken with their white mess-mates at reunions held decades after the war. . . .

Dead Confederates regulars are already familiar with the pitfalls of relying on Confederate reunion photographs.

It doesn’t look like Private Brown has been credited as a Black Confederate up to now, but I wouldn’t be surprised if that changes. The claims made for Black Confederates are often based on the flimsiest of evidence, and a headstone reading “CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY” is undoubtedly sufficient in this case, especially if one overlooks that the original stone correctly identified Brown’s regiment. That last part is a detail that, I suspect, will get overlooked in the clamor about “political correctness” and denial of Brown’s “true” Confederate heritage. After all, it is the Bay Area. I’m sure somehow this whole thing is Nancy Pelosi’s fault.

Update: The Sacramento Bee has nice coverage of the story with additional details, and the Long Beach Press-Telegram has a story from last March on Brown’s family in the Vallejo area. Below: One of Private Brown’s pension application index cards, dated January 6, 1894, via Footnote.

The Irresistible Appeal of Black Confederates

Photo by JimmyWayne, via Creative Commons License.

Over at Civil War Memory, Kevin highlights photos by Robert Pomerenk of an exhibit on “Blacks Who Wore Gray” at the Old Court House Museum in Vicksburg. The display features an original document, the 1914 pension application for former slave Ephram Roberson — the document explicitly asks for “the number of the regiment. . . in which your owner served” — but is otherwise composed of nothing but printouts of various quotes and well-known photographs of African American men in the field with Confederate troops, or (decades later) participating in reunion activities. At least one of the latter photos is credited to the neoconfederate publication Southern Partisan. The “Chandler Boys” are included, of course, though no one else whose image is displayed in the exhibit is fully identified by name and unit. One old African American man is listed only as “Uncle Lewis,” and others are not identified at all.

In terms of presenting or explaining history, the exhibit is a hopeless mess. Its organization — there actually is no organization or structure to it — is exactly the same as many Black Confederate websites, which amount to nothing more than a hodgepodge of quotes and images, unconnected either to each other or to any larger context, that make reference to African Americans in connection with Confederate troops. Like the typical Black Confederate website, there’s no distinction at all made between men who went to war as slaves and those who might have been free; one wonders if those who compile and present this material before the public have any real sense of the most basic elements of the “peculiar institution.” Several of the men shown in the Old Court House exhibit are explicitly identified as servants; there is no recognition — or at least public acknowledgment — that these men were almost certainly slaves, and had no say in whether they went off to war with their masters or not. There’s virtually no information offered about these men that would allow the visitor to get any sort of understanding of these men’s lives, either in the 1860s or in the early 20th century, as old men. There’s no attempt to flesh out their stories, to understand the details of their experiences either during the war, or after; instead, one is left with random quotes from Nathan Bedford Forrest and paeans “to the faithful slaves, who loyal to a sacred trust, toiled for the support of the Army, with matchless devotion and sterling fidelity guarded our defenseless homes, women and children, during the struggle for the principles of our Confederate States of America.” These men were soldiers, we’re asked to believe, volunteering and fighting for their homes and way of life, but they are never allowed to speak for themselves — the only ones allowed to speak on their behalf are white, and even then only to praise their loyalty and fidelity to the Confederacy.

This effort does nothing to honor these men as men. It is simply an extension of the time-honored “faithful slave” narrative, updated to make it more palatable to a modern audience. The Old Court House Museum differs from other efforts to push the case for Black Confederates only in that they actually go so far as to describe them explicitly as “faithful slaves.”

This exhibit would do far more to further the case for Black Confederates as a group if it proved the case of even a single man — Ephram Roberson, perhaps — and really provided in-depth coverage and explication of his life and role during the war and after, and proved his case as a soldier. Show us his service records, if such exist. Show us his listing in the census. Show us his property records, if there are any, or his obituary. If he was a slave, did he talk to the WPA in the 1930s? Are there contemporaneous letters or diaries from his fellow soldiers that describe his service? Track down his descendants living today and interview them. That is how history is done, through dogged research and building a case from the ground up.

But none of that is present at the Old Court House. There is no discussion of these mens’ supposed military service in the larger context of the war, no discussion of the actions they each fought in, and — most significantly — no firsthand accounts by white soldiers within those same units of their African American comrades’ service. What the Old Court House exhibit (and a hundred others on the web and in print) does is just the opposite; it takes a dozen or fifty or a hundred different, unconnected and disparate snapshots and claims that they form a larger, coherent picture. They don’t. They’re like items pulled from a dozen different families’ albums, scattered and mixed into a single pile on the floor; they do not, can not, tell anything approaching a single, cohesive story, no matter how many times they’re rearranged, e-mailed or Xeroxed.

I want to give the Old Court House Museum a pass on this exhibit, which contributes nothing at all to the making the case for Black Confederates. I began my professional career in small, local history museums not unlike this one. I spent six years, starting as an undergrad and continuing after graduation, part- and full-time, researching, writing, designing and setting up exhibits on local history. After that, I spent two years in grad school getting a masters in the field. I’m trained as a museum professional, though I haven’t worked in one for years. So I don’t walk into any museum as a purely blank slate. I even visited the Old Court House Museum once, years ago, although at the time I paid more attention to the steamboat material on display. And while I don’t know much about the specific resources available to the Old Court House — their administration and staff page is blank — I’ve got a good idea of what their situation is like, and it ain’t pretty. Small history museums like the Old Court House often get little or no direct support from local government, apart from in-kind provision of space and utilities; they have minimal paid staff, and cannot afford to hire people with significant experience or training in the field; they get by hand-to-mouth, year after year, trying to squeak by on a few thousand visitors paying a couple of bucks for admission. They are eager to give space to almost any group or person with a new or provocative idea for an exhibit, particularly if it fits well with the museum’s own preferred image of itself and the community it documents. And, as an organization dependent on the good will of the local business community — think of the chamber of commerce crowd — they’re heavily and inevitably influenced by the wishes of a small number of local patrons who may not know the first thing about history, but have very strong ideas about what they do and do not want showcased in their local museum. You’re welcome to make your own speculation who those folks are in Vicksburg.

Vicksburg looms large in the memory of the Civil War; it has been argued that the Vicksburg campaign, which cemented effective Union control of the Mississippi, was the true turning point of the war. But among the moonlight-and-magnolias image the community likes to present to tourists, it’s easy to forget that Vicksburg remains a small, poor town in a small, poor state. Fewer than 25,000 people live there; they are, on the whole, older and less-educated than the rest of the country. The median household income in Vicksburg is a little over half that of the rest of the United States; one in four families live below the poverty level, compared to one in ten nationally. Three-fifths of Vicksburg’s population is African American, a proportion that is exactly the reverse of Mississippi as a whole. Like many cities in the South, it has an ugly postwar history of racial violence and intimidation.

One might assume that the presence of the Vicksburg National Military Park would reinforce the efforts of local museums like the Old Court House; in fact, I think presence of a major Civil War site in town actually (and inadvertently) undermines the efforts of the local museum in developing a strong historical interpretive program of its own, in two ways. First, the national military park is the heavy hitter in terms of history; those in the area who have the educational background or experience are naturally drawn to the park, whether to work as administrators, guides or volunteers. Second, with the National Park Service providing a solid, but conventional, interpretation of the city’s role in the Civil War, the Old Court House Museum would naturally be drawn into serving as an “alternative” museum, presenting material and ideas that, for whatever reason, the NPS won’t touch. That’s where Black Confederates come in.

The idea of Black Confederates has a ready-made appeal. The contribution of African Americans to military service in this country has often been overlooked by both historians and popular culture. On its face, demanding recognition for African American soldiers who fought for the Confederacy sounds not unlike recognizing the achievements of the Tuskegee Airmen of World War II or the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry — both groups of African American soldiers who had to fight bigotry and doubt even to win the chance to prove themselves against the enemy. The notion of the existence of Black Confederates, while seeming contradict everything most people remember from school about the South, the war and the institution of slavery, also carries with it a certain conspiratorial appeal as well — this is the secret that Northern history books don’t want you to know. Who wouldn’t want to get let in on something like that? Recognizing African Americans serving in butternut uniforms seems like the right and just thing to do; conversely, those who express skepticism (or reject the notion outright) are easily portrayed as being motivated by elitism, prejudice or other ulterior motives to keep these mens’ service quiet, as has supposedly been done these last hundred and fifty years. They want to deny African Americans in the South their heritage. The Black Confederate narrative has a strong element of conspiracy about it, attributed to those who reject it, and like all good conspiracy theories this one is self-affirming: of course they deny these men’s existence, just like they always have. But we know better, don’t we?

I don’t know how many subscribers to the narrative of African Americans in the Confederate ranks are genuinely sincere but ill-informed and unable to recognize an historiographical con game when it’s foisted on them, and how many are willfully, cynically, spinning a line of “evidence” that they know to be composed of smoke and mirrors. As I said before, I want to give the Old Court House Museum a pass on this exhibit, because I know (or think I do) how vulnerable they are to the whims of a few well-heeled patrons, and how poorly-positioned they are to push back. But it’s hard to give them that pass. They may not know better, but they damn surely ought to.

Would Crock Davis be Considered a “Black Confederate?”

Crock Davis (c.) and Eighth Texas Cavalry veterans, San Marcos, Texas, October 29, 1913. From the Online Archive of Terry’s Texas Rangers.

One of the hotter debates in Civil War circles today is the existence of “Black Confederates,” African-American men who (it is claimed) took up arms and served as soldiers in the Southern armies. There’s little discussion of this among professional historians, who for years have looked for contemporary, primary-source documents to confirm the enlisted service of specific individuals, only to find none. On the other side of the question are Confederate heritage groups and individuals who pull together bits and fragments of pension records, newspaper accounts, oral history and outright fakery to make a claim that this man or that one served in the ranks as a soldier. While there are many reasons why and individual might take up such a claim, and a great many of them are sincere and well-intentioned (if poorly informed when it comes to historical methods), it seems very obvious that for the heritage groups pushing the idea (including but not limited to the SCV), it’s part of a larger effort to distance themselves and the Confederate ancestors they venerate from the institution of slavery, and the moral implication that goes with it. What better way to show that the Confederacy was not really about slavery, than to show that hundreds (Thousands? Tens of thousands?) of African American men willingly and voluntarily took up arms in defense of the Confederacy. The Black Confederate is nothing more than the “faithful slave” meme so central, so essential, to the Lost Cause, made more palatable for modern audiences.

No one who has more than a grade-school understanding of the Civil War has ever suggested that the Southern armies were not surrounded by African American men and women. They performed in all manner of roles, as common laborers digging trenches and setting up fortifications. The served as teamsters. They worked in all manner of service jobs, as cooks and launderers and personal “body servants.” The vast, vast majority of these men were slaves, who had no say whatsoever as to where they were to go or what they did. No one who has looked seriously at this conflict denies that African Americans were — mostly unwillingly — a central part of the Confederacy’s war effort.

The difficulty is that individuals and groups are making claims of these men having been soldiers, on little or no direct and contemporary evidence. No one questions that these men went off to war, but like the tens of thousands civilian contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan today, they were not soldiers, even though they “served” (in the broadest sense) in a combat zone. It’s really tricky trying to determine the roles of specific African-Americans who went to war with Southern troops, and given the lack of records, easy to ascribe to them status as soldiers that did not, in fact, apply. Time and again, in those cases where documentation is available, the claim that these men were recognized at the time — or even decades later — as soldiers falls apart.

In many cases, the “evidence” presented for Black Confederates consists of photos of elderly African American men, sometimes in uniform, participating in veterans’ reunions or other commemorations decades after the war ended. These are usually offered without detailed elaboration of these men’s individual histories, or even with identification of them by name. (The practice of posting unidentified photos, not coincidentally, makes it impossible for anyone else to independently check the validity of the claims now being made on their behalf.) The assumption seems to be that, if these men participated in commemorative events all those years later, that in and of itself confirms that they served as soldiers in the war. That’s not true, and the case of Crock Davis gives a good example of how complex these men’s involvement with Confederate veterans’ groups can be.

Recently I was digging through the website for the Eighth Texas Cavalry (Terry’s Rangers), and noticed that in two photos of early 20th century reunions (1905 in Austin and 1913 in San Marcos), there are African American men present in the group. One of these men is Crockett Davis. While (as far as I know) no one has explicitly claimed Davis had been a soldier in that unit, it would be very easy to do so, based on his presence at at least two Ranger reunions. I suspect that much of what is claimed as “evidence”of Black Confederates is based on nothing more than exactly this sort of fragmentary bits of information.

The Ranger reunions were well-covered in the regional press, and the 1913 meeting in San Marcos got extended write-ups in my local paper, on October 29 and 30, 1913. The October 29 story listed him and his hometown among the attendees, as “Crock Davis (colored), Smithville.” That, along with the photo, could easily be taken as evidence of Davis’ having been a trooper in the Rangers. But the next day’s article, tells a more complex story, both about Davis’ wartime service and his status within the Ranger veteran’s group (and with apologies for the contemporary language):

An interested and quiet spectator at all sessions has been an old time “before-the-war” darkey, Crockett Hill, of Smithville, known to all the rangers as “Uncle Crock.” His curly hair is whitened with the years, but he steps briskly and tells with pride that he went all through the war with the rangers as cook and body servant of D. O. and Tom Hill of Smithvllle, and that he never missed a reunion. In the banquet he was not overlooked, but served at a side table along with “his white folks.”

This short paragraph really tells the story. There are three distinct elements here that clearly define both Davis’ wartime status, and his position within the veterans’ group a half-century later.

First, this profile lists Davis’ surname as Hill, the name of his former masters. This was not the name he gave reporters the day before, nor is it the name he went by in his day-to-day life as recorded on multiple census rolls as far back as 1880. But at the Terry’s Rangers reunion — at the meeting where his former master was elected president of the organization — when he’s described by others he’s identified as Crock Hill.

Second, Davis’ wartime role as “cook and body servant” is explicitly defined. There is no suggestion of Davis being recognized as an Eighth Texas trooper. There is no mention (by Davis or anyone else) that he ever took up arms in combat.

Third (and most telling to me), is the note that Davis was an “interested and quiet spectator” at the meeting — showing pretty clearly that he took no active part in the business of the organization. Further, at the veterans’ banquet that evening, he was seated at a side table apart from the white veterans. It’s excruciatingly clear that even fifty years on, the old Confederates did not accept Davis to be a veteran of the same status as they themselves, even though he “went all through the war with the rangers.” (The Hill Brothers were active in the veterans’ group, one of them being elected president at the same meeting. It seems a fair question whether Davis would have been as welcomed at the ranger reunions had the brothers not been present.) Crock Davis was no more considered a trooper of the Eighth Texas Cavalry in 1913 than he had been a half-century before.

My point here is not to suggest that the white veterans of Terry’s Rangers still thought of Davis as a slave, or that he was compelled to attend multiple reunions. I’m certain that there was a real sense of affection and bonhomie on both sides. But it’s equally certain that even after fifty years, there remained an unbridgeable gap between the old men.

To be sure, the Terry’s Rangers website makes no explicit claim that Davis — whom they list as “Hill” — was a soldier during the war, only that he was a member of the veterans’ association. I cannot confirm that he was actually a member, only that he attended the meetings. But it would be very easy for someone to claim that Davis was a Black Confederate, although a little diligent research — say, about an hour’s worth, using entirely online resources — would definitively disprove such a claim. I wonder how many African American men now being identified as Confederate soldiers are like Crock Davis — men who went to war as slaves, and even fifty years later were still not accepted by their fellows as peers.

11 comments