Missing the Forest for the Trees

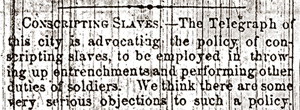

While going through microfilm looking for something else, I came across this editorial in the Galveston Weekly News, published on September 3, 1862 — several months after the Confederacy’s first Conscription Act, and shortly before passage of the second.

While going through microfilm looking for something else, I came across this editorial in the Galveston Weekly News, published on September 3, 1862 — several months after the Confederacy’s first Conscription Act, and shortly before passage of the second.

Conscripting Slaves. — The Telegraph of this city [Houston] is advocating the policy of conscripting slaves, to be employed in throwing up entrenchments and performing the other duties of soldiers. We think there are some very serious objections to such a policy. We do not propose to enter upon the discussion of the subject, but would here simply remark that by adopting such a policy we would seem to be following the example of the enemy, and they would not fail to justify the course they are now pursuing in filling up their armies with negro [sic.] recruits, by referring to the fact that we make conscripts of our slaves in order to strengthen our armies against them. The fact of our not putting arms in the hands of slaves, would not deprive their argument of its force, so long as the slaves are employed to the usual duties of soldiers, so that the 100,000 of them the Telegraph proposes to raise, will have the same effect as increasing our military force by just that number of white conscripts. We fear the argument would, at least, be sufficient with foreign nations, to justify the Federals in employing negroes in their armies, in the way they are now doing.

We also think the policy proposed would be seriously objectionable on the ground of its taking the slave out of his proper position, and the only position he can safely occupy in a slave country. We are moreover of the opinion that we have white men enough to achieve our independence without conscripting slaves to help us. And we further believe that our slaves can be much more profitably employed in agricultural, mechanical and manufacturing pursuits, under the supervision f white men. In these pursuits, their labor, if properly directed, will add more military strength to the country, by keeping our armies properly supplied, than by conscripting them.

My emphasis. Note that the editorial here objects to the formal enlistment of slaves even in non-combatant roles — “the fact of our not putting arms in the hands of slaves, would not deprive [the Federals’] argument of its force.” In the back-and-forth about this or that bit of “evidence” for the widespread enlistment of large numbers of African Americans as soldiers in the Confederate Army — much of which is either fundamentally misunderstood, self-contradictory, willfully misrepresented or flat-out fabricated — it’s easy to miss the forest for the trees. The very idea of organizing slaves into military formations, under arms, was antithetical to the legal, social and racial fabric that defined the Confederacy and that put the Southern states on the path to secession. There were dissenting voices, to be sure, particularly as the war dragged on and the Confederacy’s military position became increasing perilous. But even in the closing weeks of the war, the very notion of enlisting slaves into combat service remained deeply, fundamentally offensive to many whose devotion to the Confederacy was without question. “Use all the negroes you can get,” Howell Cobb advised the Confederate Secretary of War in January 1865, “for all the purposes for which you need them, but don’t arm them. The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution.”

One sometimes hears, when skeptics point out the dearth of contemporary primary sources from the Confederate side that describe African Americans serving in the ranks, under arms, recognized as soldiers by their officers and their peers, that the practice was so commonplace, so unremarkable, that it simply wasn’t commented upon. It’s suggested that the Confederate Army was racially integrated to such a degree no one thought to mention it. Such a claim reflects a deep ignorance — or deep dishonesty — about the most basic reality the Confederate States: it was a nation succinctly, accurately and unabashedly described in the Weekly News‘ editorial as “a slave country.”

Confederate Reunions: Simple Images, Complex Realities

About a year ago the blog Confederate Digest posted an image from the Alabama Department of Archives and History, showing participants at what was billed as the “Last Confederate Reunion,” held at Montgomery, Alabama in September 1944. The African American man at center is identified, from the archives’ catalog description, as Dr. R. A. Gwynne of Birmingham, Alabama. No additional information about Dr. Gwynne is provided, and there seems to be an unspoken assertion that his presence is evidence of his service as a soldier, and there is an implicit assumption that he was viewed at the time as a co-equal peer of the white veterans. But as with Crock Davis and the Eighth Texas Cavalry, the reality is more complex, and reflects the social and cultural minefield of both the antebellum and Jim Crow South.

As it happens, the Alabama archive website also includes a copy of the issue of the Alabama Historical Quarterly (Vol. 06, No. 01, Spring Issue 1944) containing a detailed description of the event. The attendees are described thus:

Commander-in-Chief of the Confederate Veterans, Homer L. Atkinson, of Petersburg, Va., was unable to attend on account of illness. The first Veteran to arrive was Brigadier-General W. M. Buck, of Muscogee, Oklahoma, who has already reached the age of 93 but is remarkably active and came from Muscogee to Montgomery unescorted. The Georgia delegation was sent through the courtesy of Governor Ellis Arnall in a beautiful car escorted by the Georgia State Highway Patrol in charge of Corp. Paul Smith. In the delegation were Col. W. H. Culpepper, 96 years of age and Gen. W. L. Bowling, 97. Other Veterans present were: Gen. J. W. Moore, of Selma, 93 years of age, who was elected at the close of the Reunion to be Commander-in-Chief of the Veterans; J. D. Ford, Marshall, Texas, 95 years of age; W. W. Alexander, Rock Hill, S. C., 98; Gen. William Banks, Houston, Texas, 98; J. A. Davidson, Troy, 100 years of age. All Veterans except Gen. Buch were accompanied by attendants.

There’s no mention of Dr. Gwynne, only the seven white veterans. There follows a long description of the various activities at the reunion, speeches, musical performances and so on (“Mrs. Thomas wore a Scarlett O’Hara dress and received vociferous applause when she sang ‘Shortenin’ Bread'”), and then, tacked on at the end of the piece, is a brief note:

In the group of seven Veterans [sic., eight men total, seven white and one black] that posed for a photograph was one Negro man slave 90 years of age who served in the war as a body guard to his master. This man, Dr. R. A. Gwynne, lives in Birmingham where he is a well known character.

This, along with the caption accompanying the photo, is the only mention of Dr. Gwynne in the account of the reunion. It seems clear from the context that Dr. Gwynne was, even in 1944, considered separate and apart from the white veterans. He’s almost literally an afterthought. As I said, we’ve seen this before.

In the comments section of the original post, blogger Corey Meyer pointed out — with more than a little snark — that Dr. Gwynne’s seated position may indicate his status was considered different than that of the others in the photo. The blog host fired back with speculation that Dr. Gwynne may have had an infirmity that kept him from standing, suggested that Meyer was arguing that Dr. Gwynne was somehow forced to participate in the reunion “against his will,” and repeated the standard tropes about the “indisputable fact that thousands of blacks, both slave and free, willingly served in the Confederate armed forces, defending their homeland against a brutal, invading northern army.” Another commenter, well-known on Confederate heritage sites, chimed in with some gratuitous name-calling directed against Meyer.

This is, sadly, the way online “discussions” about “black Confederates” generally go — lots of sarcasm, rancor and name-calling, with little or no attention paid to the individual subject, and no acknowledgment or understanding of the larger context of the periods under discussion, either the 1860s or early 20th century South. In this case, Dr. Gwynne gets completely overlooked, because his only role here is to serve as a convenient example of the “thousands of blacks, both slave and free, willingly served in the Confederate armed forces, defending their homeland against a brutal, invading northern army.” (Entirely disregarded is the fact that, if Dr. Gwynne was indeed 90 years old in September 1944, he could not have been more than eleven at the end of the Civil War, a child even by 19th century standards.)

This, too, is entirely typical of the way images of old African American men at Confederate reunions are used as “evidence” of those men having been considered soldiers. Most of the time, these images are splashed out on a website without any further explanation and without full identification of the men involved, the units they were affiliated with, or even the date and location of the reunion. This 1944 example is better in that the man in question is identified, but the intended point is still the same — that Dr. Gwynne’s presence is proof “that thousands of blacks, both slave and free, willingly served in the Confederate armed forces, defending their homeland against a brutal, invading northern army.” It’s not; it’s only evidence that Dr. Gwynne attended the event, and posed for a photo with the white veterans. The photos says nothing conclusive about his status during the war, how he was viewed by those same white veterans, or what his motivations or beliefs were when, as an enslaved child, he was taken off to war to serve as a “body guard” to an unknown master.

I haven’t been able to find much on Dr. Gwynne in the usual online sources for contemporary newspapers, census records and the like. I suspect that he may have been a clergyman, rather than a physician, but I don’t know. I’ll keep looking. It remains an open question how much, and in what role, Dr. Gwynne participated in the reunion festivities; we know that in Crock Davis’ case thirty years previous, he was silent spectator at the veterans’ business meeting, and did not eat at the same banquet table with the white veterans. Did a similar, Jim Crow standard apply to Dr. Gwynne at the “Last Confederate Reunion” in Jackson in 1944, or to other Confederate reunions across the South in the decades previous? It sure seems like a mistake to assume that it didn’t, or that views on race and social position of black servants held by the white soldiers of 1861-65 had completely disappeared in the intervening decades.

No serious historian has ever, to my knowledge, questioned that black men, most of the them former slaves and personal servants, participated in Confederate reunions from the 1890s onward. It would be surprising if at least some men didn’t, given the social pressures of the time and the pervasiveness of the “faithful slave” meme that helped define the Lost Cause. John Brown Gordon, commander of the United Confederate Veterans, described it at the time, observing that “these faithful servants at that time boasted of being Confederates, and many of them meet now with the veterans in their reunions, and, pointing to their Confederate badges, relate with great satisfaction and pride their experiences and services during the war. One of them, who attends nearly all the reunions, can, after a lapse of nearly forty years, repeat from memory the roll call of the company to which his master belonged.” The great Southern historian Bell Irvin Wiley, writing just a few years before the “Last Confederate Reunion,” devoted an entire chapter of his classic Southern Negroes, 1861-1865 to black body servants and their complex and (often distinctly unfaithful) relationship with their masters. It’s a very complex business, as Wiley relates, but even he noted that “even now [1938], gray-haired Negroes, dressed in ‘Confederate Gray,’ are among the most honored veterans in attendance at soldier’s reunions.” They were honored by white Confederate veterans explicitly because they embodied the “faithful slave” meme that was central to the way the Confederacy was consistently portrayed by most Southerners at the time, and by some right up to today. I don’t doubt that Dr. Gwynne (and Crock Davis, and Bill Yopp and. . . .) gladly took part in these events, and took a measure of pride in their involvement in the war. But at the same time, their professed pride in the Confederate cause served a larger purpose for white Southerners, and (knowingly or not) those black men took on a role carefully crafted as part of the Lost Cause tradition, that of the loyal slave, still faithful to both his master and to the cause, decades later. They were honored and valued because they did this, as much as for their service to their masters decades before.

People are complicated, and often their true motivations and beliefs are impossible to know. But we do a real disservice to the past to use the sort of historical shorthand offered in the case of Dr. Gwynne or dozens of other unnamed black men photographed at Confederate reunions, that their presence is prima facie evidence of the their having been soldiers, and accepted as co-equal peers by the white veterans. That is, to borrow a line commonly used as a cudgel by Southern heritage groups on those who disagree with them, a singularly bad case of “presentism,” using fragments of the historical record to make the case for an entirely modern and self-serving interpretation. The actual contemporary evidence, when available, suggests otherwise. It does not honor these men to present them as something they were not, nor does it credit the research skill or integrity of the person making the claim.

John B. Gordon, “Faithful Servants,” and Veterans’ Reunions

Recently I came across a passage in General John B. Gordon’s Reminiscences of the Civil War (1903, pp. 382-84) that, while discussing the eleventh-hour decision of the Confederate government to enlist slaves as soldiers in the final weeks of the conflict, reveals a great deal about the nature of slaves’ other service in the Confederate army, and how they themselves sometimes presented themselves both during the war and decades later.

John Brown Gordon (1832-1904) was an attorney with no military experience when the war began, but he was elected captain of a company he raised, and by late 1862 had been promoted to the rank of brigadier general. He quickly became famous for his bravery under fire, and was wounded numerous times. He served throughout the war with the Army of Northern Virginia, eventually rising to the rank of major general (he claimed lieutenant general), and commanding the Second Corps of that army. Gordon saw action at most of the Army of Northern Virginia’s major engagements, including First Manassas, Malvern Hill, Sharpsburg, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and the Siege of Petersburg. Gordon surrendered his command to another famous civilian-turned-general, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, in April 1865. After the war, he fought against Reconstruction policies — allegedly as a leader of the Klan — and later served as a U.S. senator and as governor of Georgia. In 1890 he was elected first Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans, a post he held until his death.

John Brown Gordon (1832-1904) was an attorney with no military experience when the war began, but he was elected captain of a company he raised, and by late 1862 had been promoted to the rank of brigadier general. He quickly became famous for his bravery under fire, and was wounded numerous times. He served throughout the war with the Army of Northern Virginia, eventually rising to the rank of major general (he claimed lieutenant general), and commanding the Second Corps of that army. Gordon saw action at most of the Army of Northern Virginia’s major engagements, including First Manassas, Malvern Hill, Sharpsburg, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and the Siege of Petersburg. Gordon surrendered his command to another famous civilian-turned-general, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, in April 1865. After the war, he fought against Reconstruction policies — allegedly as a leader of the Klan — and later served as a U.S. senator and as governor of Georgia. In 1890 he was elected first Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans, a post he held until his death.

In his memoir, Gordon describes the debate surrounding the proposed enlistment of slaves in the Confederate army in the closing weeks of the war:

Again, it was argued in favor of the proposition that the loyalty and proven devotion of the Southern negroes [sic.] to their owners would make them serviceable and reliable as fighters, while their inherited habits of obedience would make it easy to drill and discipline them. The fidelity of the race during the past years of the war, their refusal to strike for their freedom in any organized movement that would involve the peace and safety of the communities where they largely outnumbered the whites, and the innumerable instances of individual devotion to masters and their families, which have never been equaled in any servile race, were all considered as arguments for the enlistment of slaves as Confederate soldiers. Indeed, many of them who were with the army as body-servants repeatedly risked their lives in following their young masters and bringing them off the battlefield when wounded or dead. These faithful servants at that time boasted of being Confederates, and many of them meet now with the veterans in their reunions, and, pointing to their Confederate badges, relate with great satisfaction and pride their experiences and services during the war. One of them, who attends nearly all the reunions, can, after a lapse of nearly forty years, repeat from memory the roll call of the company to which his master belonged.

My emphasis. Like another dyed-in-the-wool, senior and well-connected Confederate general, Howell Cobb, Gordon discusses the proposal to enroll slaves as soldiers without making any mention of the supposedly-widespread practice of African Americans serving in exactly that capacity.

Far more important, though, is what he does say. Gordon’s description of enslaved body servants, and their ongoing attachment to the Confederacy, is essential. He notes that they “boasted of being Confederates, and many of them meet now with the veterans in their reunions, and, pointing to their Confederate badges, relate with great satisfaction and pride their experiences and services during the war.” This is a critical observation, and explains much of what is now taken as “evidence” of African American men serving as soldiers during the war. Advocates for the notion that large numbers of black men served as soldiers in the Confederate army routinely point to images of elderly African American men at veterans’ reunions and argue that those men wouldn’t have been present had they not been seen as co-equal soldiers themselves. As we’ve seen, the historical record, when available, can disprove that assumption. And now we have General John B. Gordon, Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans, writing exactly the same thing about what he saw around him, as the popularity of veterans’ reunions reached its peak. Gordon clearly takes pride in the former slaves’ commitment to the memory of the Confederacy — again, “faithful servants” — but he never credits any greater wartime service to them. Indeed, Gordon continues with an anecdote mocking the idea of such men being considered soldiers:

General Lee used to tell with decided relish of the old negro (a cook of one of his officers) who called to see him at his headquarters. He was shown into the general’s presence, and, pulling off his hat, he said, “General Lee, I been wanting to see you a long time. I ‘m a soldier.”

“Ah? To what army do you belong—to the Union army or to the Southern army ?”

“Oh, general, I belong to your army.”

“Well, have you been shot ?”

“No, sir; I ain’t been shot yet.”

“How is that? Nearly all of our men get shot.”

“Why, general, I ain’t been shot ’cause I stays back whar de generals stay.”

This anecdote reinforces Gordon’s (and Lee’s) dismissal of the idea that the service of black men like the cook should be considered soldiers; what made the story amusing to both generals is that the man’s claim to status as a soldier was, to their thinking, preposterous on its face. To be sure, Gordon shows real affection for these old African American men who, in his view, remain loyal to the cause. Nonetheless, he can’t help but make gentle mockery of their pretensions to be soldiers. He never considered them to be soldiers in their own right, which is the point of heaping praise on them as “faithful servants.” Lee understood that, Gordon understood that, and Gordon counted on his readers in 1903 to understand that.

So why is that so hard to understand now?

Fisking Fremantle

Recently I uploaded a post in which I characterized Dr. Steiner’s famous account of Confederate troops entering Frederick, Maryland in 1862 as being unreliable, because (among other things) it was uncorroborated by other witnesses to the same event. The credibility of Steiner’s account is important, as it’s one of the references often cited as evidence of large formations of black soldiers serving in the Confederate Army. Steiner estimates their number as “over 3,000 Negroes” — an enormous number, something approaching the size of a full-strength brigade.

One of my commenters took me to task, saying that Steiner’s account is corroborated by the Fremantle Diary, an account of a British 0fficer’s travels across the Confederacy in the spring and early summer of 1863, and culminating with his witnessing the Battle of Gettysburg. I pointed out that Fremantle didn’t witness the Confederates’ entry into Frederick the previous fall, but my commenter assured me, “it’s the same army.”

This struck me as odd. Fremantle and I are old friends, as it were, since I first read his account years back while working on an archaeology project. I thought I was familiar with Fremantle’s account, but I sure couldn’t recall any references to Black Confederates in it. Furthermore, any reference to Black Confederates in “the same army” would be restricted to a relatively small part of the book, that covered Fremantle’s time with the Army of Northern Virginia — Chapters 10 through 13. I skimmed those chapters, and then the entire text, and came up empty.

So I did some Googling and came up with two brief passages that are cited over and over again on Black Confederate sites, such as this one. Fremantle’s texts are rarely quoted in full, but are most often summarized, which is the crux of the problem. More about that in a moment.

The first passage in Fremantle comes in a description of McLaws’ Division, marching north toward Pennsylvania, on June 25, 1863:

The weather was cool and showery, and all went swimmingly for the first fourteen miles, when we caught up M’Laws’s division, which belongs to Longstreet’s corps. As my horse about this time began to show signs of fatigue, and as Lawley’s pickaxed most alarmingly, we turned them in to some clover to graze, whilst we watched two brigades pass along the road. They were commanded, I think, by Semmes and Barksdale, and were composed of Georgians, Mississippians, and South Carolinians. They marched very well, and there was no attempt at straggling; quite a different state of things from Johnston’s men in Mississippi. All were well shod and efficiently clothed.

In the rear of each regiment were from twenty to thirty Negro slaves, and a certain number of unarmed men carrying stretchers and wearing in their hats the red badges of the’ ambulance corps; this is an excellent institution, for it prevents unwounded men falling out on pretense of taking wounded to the rear. The knapsacks of the men still bear the names of the Massachusetts, Vermont, New Jersey, or other regiments to which they originally be tonged. There were about twenty wagons to each brigade, most of which were marked U. S., and each of these brigades was about 2,800 strong. There are four brigades in M’Laws’s division. All the men seem in the highest spirits, and were cheering and yelling most vociferously·

Fremantle explicitly identifies the African American men as slaves. He makes no mention of arms or weapons, but does describe them as being “in the rear” of each regiment — i.e., not actually part of the formation of companies, along with the stretcher-bearers. There’s no suggestion that Fremantle viewed these men as soldiers. Nonetheless, some authors have written secondary accounts describing Fremantle’s observations, with some careful rephrasing that changes the the meaning entirely. An example of this is a post by James Durney over at the TOCWOC Blog:

[Fremantle] states that every regiment and battery has from 20 to 40 [sic.] black men traveling with it. His description of their dress and arms is similar to the description of Jackson’s command in 1862. This indicates that Lee’s army had not changed any policies and still contained a substantial number of black men. Longstreet had 72 regiments and batteries with just under 21,000 men carried on the rolls. If we use 20 black men with each battery and 30 with each regiment Longstreet’s Corps in July 1863 had just under 2,000 black men embedded in the units, an additional 9.4% above the official muster rolls.

Fremantle does not, in fact, make a blanket statement that “every regiment and battery” has a similar number of men traveling with it; he only describes the regiments he saw, those of Semmes’ and Barksdale’s Brigades, eight infantry regiments in all. Fremantle makes no mention of batteries in this context. He gives no description of these black mens’ dress. And significantly, Mr. Durney never uses the term Fremantle openly did — slaves — to describe the men traveling with each regiment, which further clouds their actual status and makes it possible for the reader to come away thinking they are soldiers. This summary is misleading and attributes to Fremantle claims that, in fact, the Englishman never made.

The second passage from Fremantle dates from July 6, the third day after the battle, during the Confederate retreat along the Hagerstown Pike, somewhere northeast of that town:

At 12 o’clock we halted again, and all set to work to eat cherries, which was the only food we got between 5 A. M. and 11 P. M.

I saw a most laughable spectacle this afternoon – a Negro dressed in full Yankee uniform, with a rifle at full cock, leading long a barefooted white man, with whom he had evidently changed clothes. General Longstreet stopped the pair, and asked the black man what it meant. He replied, “The two soldiers in charge of this here Yank have got drunk, so for fear he should escape I have took care of him, and brought him through that little town.” The consequential manner of the Negro, and the supreme contempt with which he spoke to his prisoner, were most amusing.

This little episode of a Southern slave leading a white Yankee soldier through a Northern village, alone and of his own accord, would not have been gratifying to an abolitionist. Nor would the sympathizers both in England and in the North feel encouraged if they could hear the language of detestation and contempt with which the numerous Negroes with the Southern armies speak of their liberators.

The man is explicitly identified as being a slave; there’s nothing to indicate he’s a soldier, no reference to his own uniform, or even specifically that the weapon he carried was his own. There’s simply the explanation that the two Confederate soldiers who were supposed to guard the prisoner were drunk, so this man took over their job that they were incapable of, rather than let the Union man escape.

Further, Fremantle’s observation that “the consequential manner of the Negro, and the supreme contempt with which he spoke to his prisoner, were most amusing” is a dead giveaway that the black man’s ordinary status is far lower than his prisoner’s; that’s what makes it funny. A Confederate soldier heaping verbal abuse on a Federal isn’t noteworthy; in the context of the time and place, a slave holding a Yankee at gunpoint and giving him what for most certainly would have been seen as comical. It’s a joke not unlike the famous incident where a former slave, now in the USCT, chided a group of sulking Southern civilians standing by the roadside: “bottom rail on top, now.”

This passage of Fremantle’s has also been misrepresented. Again, Durney:

Fremantle recounts an incident where an armed black man, dressed in Confederate and Union uniform items, escorts Union prisoners of war to the rear.

In fact Fremantle makes no mention whatever of Confederate “uniform items,” and the black man is escorting a solitary prisoner. Again Mr. Durney omits Fremantle’s explicit identification of the black man as a slave. He omits too the black man’s explanation of taking charge of the prisoner on his own initiative, leaving the reader with the impression that prisoner escort was his assigned duty.

But wait, there’s more. As a footnote to that last paragraph, Fremantle adds this:

From what I have seen of the Southern Negroes, I am of opinion that the Confederates could, if they chose, convert a great number into soldiers; and from the affection which undoubtedly exists as a general rule between the Slaves and their masters, I think that they would prove more efficient than black troops under any other circumstances. But I do not imagine that such an experiment will be tried, except as a very last resort. . . .

So Fremantle takes the example of the slave taking charge of the Union prisoner and uses it as an opportunity to give his thoughts on the viability of enlisting blacks as soldiers, “if they chose.” He’s not discussing the success or advantages of a system that he’s seen, but describing what he thinks the prospects for it are if they chose. But Fremantle is resigned that “such an experiment will [not] be tried, except as a very last resort.” Far from documenting an example of African Americans serving as Confederate soldiers, Fremantle uses the case of the man in the blue uniform to argue that they would make acceptable soldiers if the Confederacy would allow it. Fremantle’s footnote, in particular, completely undermines the notion that his anecdote describes an actual Confederate soldier.

The title of this post is “Fisking Fremantle” because I like alliteration. But in truth, Fremantle’s not the problem. He reported what he saw and, despite his obvious sympathies with the Confederates he met, is generally considered a fair and reliable observer. The problem lies with the folks who (1) have read Fremantle’s observations and, through carelessness or intent, misrepresent them, and (2) those who repeat those same misrepresentations over and over again without checking them. It’s a shame, because what Fremantle actually wrote is fascinating on its own, and his speculation that “such an experiment will [not] be tried, except as a very last resort” is prescient. The folks who pull this example out of the Englishman’s book and cite it as evidence of Black Confederates are putting forward an account that doesn’t provide evidence of Black Confederates. Do these folks ever read the texts they’re so good at citing as proof of their case?

Yeah, don’t answer that.

________________

Image: James Lancaster as Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle in Gettysburg (1993).

“The negro has no qualities out of which a soldier can be manufactured”

On June 15, 1864, the Galveston Daily News reprinted this brief editorial from the Richmond Whig & Public Advertiser, excoriating the value of slaves as soldiers, and boasting that the Federal army’s “unnatural and diabolical” enlistment of black troops “renders their overthrow more certain and speedy.”

NEGRO TROOPS. — The catastrophe of the Yankees at Fort Pillow, like their rout at Ocean Pond [Olustee, Florida], and other mishaps that have befallen them of late, is attributed by themselves to the cowardice of their negro [sic.] allies. We are well satisfied that the result in each of the cases would have been the same, if the places of the negroes had been held by Yankees. But at the same time we believe that the presence of the negroes hastened our victories and made them easier. We need not say to Southern readers that the negro has no qualities out of which a soldier can be manufactured. Any reliance on him in that way is sure to bring disappointment and disaster. An army composed in any degree of such troops is an army with a weak point, that may always be beaten through by an adversary who knows how to use his opportunities. Hence it is that we hold that the enrollment of negro troops has brought into their armies an element of positive weakness, and given us a great advantage. The unnatural and diabolical attempt to turn slaves against their own masters reacts upon those who conceived the villany, and renders their overthrow more certain and speedy. In this as in other ways, the institution of slavery is being miraculously vindicated by the events of the war.

It would seem that the Richmond Whig was unfamiliar with that famous “integrated” local militia unit, the Richmond Howitzers. It’s another case where real Confederates didn’t know about Black Confederates.

It’s worth noting, too, that the writer makes a distinction (second sentence) between “Yankees” and “negroes” [sic.] — revealing quite clearly that, in his view, U.S. Colored Troops are not just inferior to, but completely different from, conventional, white Federal troops; the color of their uniform is not what defines them. Black Confederate orthodoxy requires one to believe that large numbers of African Americans were enlisted into Confederate service, and that their race was considered irrelevant to their skill as soldiers. It’s hard to imagine the author of this editorial being convinced of either premise.

Real Confederates Didn’t Know About Black Confederates

Lots of folks are familiar with Howell Cobb’s famous line, offered in response to the Confederacy’s efforts to enlist African American slaves as soldiers in the closing days of the war: “if slaves make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong.” It was part of a letter sent to Confederate Secretary of War James A. Seddon, in January 1865:

The proposition to make soldiers of our slaves is the most pernicious idea that has been suggested since the war began. It is to me a source of deep mortification and regret to see the name of that good and great man and soldier, General R. E. Lee, given as authority for such a policy. My first hour of despondency will be the one in which that policy shall be adopted. You cannot make soldiers of slaves, nor slaves of soldiers. The moment you resort to negro [sic.] soldiers your white soldiers will be lost to you; and one secret of the favor With which the proposition is received in portions of the Army is the hope that when negroes go into the Army they will be permitted to retire. It is simply a proposition to fight the balance of the war with negro troops. You can’t keep white and black troops together, and you can’t trust negroes by themselves. It is difficult to get negroes enough for the purpose indicated in the President’s message, much less enough for an Army. Use all the negroes you can get, for all the purposes for which you need them, but don’t arm them. The day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves make good soldiers our whole theory of slavery is wrong — but they won’t make soldiers. As a class they are wanting in every qualification of a soldier. Better by far to yield to the demands of England and France and abolish slavery and thereby purchase their aid, than resort to this policy, which leads as certainly to ruin and subjugation as it is adopted; you want more soldiers, and hence the proposition to take negroes into the Army. Before resorting to it, at least try every reasonable mode of getting white soldiers. I do not entertain a doubt that you can, by the volunteering policy, get more men into the service than you can arm. I have more fears about arms than about men, For Heaven’s sake, try it before you fill with gloom and despondency the hearts of many of our truest and most devoted men, by resort to the suicidal policy of arming our slaves.

No great surprise here; earnest and vituperative opposition to the enlistment of slaves in Confederate service was widespread, even as the concussion of Federal artillery rattled the panes in the windows of the capitol in Richmond.

What’s passing strange, as Molly Ivins used to say, is that Howell Cobb is a central figure in one of the canonical sources in Black Confederate “scholarship,” the description of the capture of Frederick, Maryland in 1862, published by Dr. Lewis H. Steiner of the U.S. Sanitary Commission. In his account of the capture and occupation of the town, Steiner makes mention of

Over 3,000 Negroes must be included in this number [of Confederate troops]. These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast-off or captured United States uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the Negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie-knives, dirks, etc. . . and were manifestly an integral portion of the Southern Confederate Army.

This passage is often repeated without critique or analysis, and offered as eyewitness evidence of the widespread use of African American soldiers by the Confederate Army. Indeed, Steiner’s figure is sometimes extrapolation to derrive an estimate of black soldiers in the whole of the Confederate Army, to number in the tens of thousands.

But, as history blogger Aporetic points out, Steiner’s observation is included in a larger work that mocks the Confederates generally, is full of obvious exaggerations and caricatures, and is clearly written — like Frederick Douglass’ well-known evocation of Black Confederates “with bullets in their pockets” — to rally support in the North to the Union cause. It is propaganda. Most important, Steiner’s account of Black Confederates under arms is entirely unsupported by other eyewitnesses to this event, North or South. Aporetic goes on to point out the apparent incongruity of Steiner’s description of this horde being led by none other than Howell Cobb:

A drunken, bloated blackguard on horseback, for instance, with the badge of a Major General on his collar, understood to be one Howell Cobb, formerly Secretary of the United States Treasury, on passing the house of a prominent sympathizer with the rebellion, removed his hat in answer to the waving of handkerchiefs, and reining his horse up, called on “his boys” to give three cheers. “Three more, my boys!” and “three more!” Then, looking at the silent crowd of Union men on the pavement, he shook his fist at them, saying, “Oh, you d—d long-faced Yankees! Ladies, take down their names and I will attend to them personally when I return.” In view of the fact that this was addressed to a crowd of unarmed citizens, in the presence of a large body of armed soldiery flushed with success, the prudence — to say nothing of the bravery — of these remarks, may be judged of by any man of common sense.

The Black Confederate crowd doesn’t usually include this second passage describing the same event, or explain Cobb’s apparent profound amnesia when it comes to the employment of African Americans in Confederate ranks. How is it, one wonders, that the same Howell Cobb who supposedly led thousands of black Confederate soldiers into Frederick in 1862 found the very notion of enlisting African Americans into the Confederate military a “most pernicious idea” just twenty-seven months later? How is it that the general who called on his black troops to give three cheers, then “three more, my boys!” came to believe that “the day you make soldiers of them is the beginning of the end of the revolution?” How is it that the commander of successful black soldiers felt that “as a class they are wanting in every qualification of a soldier?”

But set aside Dr. Steiner’s propogandist account for the moment; it’s unreliable and unsupported by other sources. Events at Frederick aside, how is that Howell Cobb, in January 1865, was unaware of the thousands, or tens of thousands, of African Americans soldiers supposedly serving in Confederate ranks across the South?

Howell Cobb’s Confederate bona fides are unimpeachable, and throughout the war he was irrevocably tied in to both political and military affairs. In his career he was, in turn, a five-term U.S. Representative from Gerogia, Speaker of the U.S. House Representatives, Governor of Georgia, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Speaker of the Provisional Confederate Congress, and Major General in the Confederate Army. He was a leader of the secession movement, and was elected president of the Montgomery convention that drafted a constitution for the new Confederacy. For a brief period in 1861, between the establishment of the Confederate States and the election of Jefferson Davis as its president, Speaker Cobb served as the new nation’s effective head of state. In his military career, Cobb held commands in the Army of Northern Virginia and the District of Georgia and Florida. He scouted and recommended a site for a prisoner-of-war camp that eventually became known as Andersonville; his Georgia Reserve Corps fought against Sherman in his infamous “March to the Sea.” Cobb commanded Confederate forces in a doomed defense of Columbus, Georgia in the last major land battle of the war, on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865, the day after Abraham Lincoln died in Washington, D.C. Perhaps more than any other man, Howell Cobb’s career followed the fortunes of Confederacy — civil, political and military — from beginning to end.

Howell Cobb’s Confederate bona fides are unimpeachable, and throughout the war he was irrevocably tied in to both political and military affairs. In his career he was, in turn, a five-term U.S. Representative from Gerogia, Speaker of the U.S. House Representatives, Governor of Georgia, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, Speaker of the Provisional Confederate Congress, and Major General in the Confederate Army. He was a leader of the secession movement, and was elected president of the Montgomery convention that drafted a constitution for the new Confederacy. For a brief period in 1861, between the establishment of the Confederate States and the election of Jefferson Davis as its president, Speaker Cobb served as the new nation’s effective head of state. In his military career, Cobb held commands in the Army of Northern Virginia and the District of Georgia and Florida. He scouted and recommended a site for a prisoner-of-war camp that eventually became known as Andersonville; his Georgia Reserve Corps fought against Sherman in his infamous “March to the Sea.” Cobb commanded Confederate forces in a doomed defense of Columbus, Georgia in the last major land battle of the war, on Easter Sunday, April 16, 1865, the day after Abraham Lincoln died in Washington, D.C. Perhaps more than any other man, Howell Cobb’s career followed the fortunes of Confederacy — civil, political and military — from beginning to end.

And yet, after almost four years of war and almost three years of commanding large formations of Confederate troops in the field, in January 1865 Howell Cobb seemingly remained unaware of the thousands, or tens of thousands, of African Americans now claimed to have been serving in Southern ranks throughout the war.

It is passing strange, is it not?

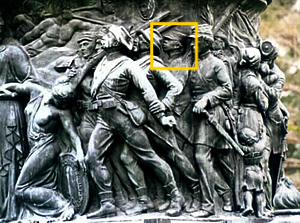

Oh, About that Black Confederate at Arlington. . . .

One of the oft-cited elements in discussion of Black Confederates is the inclusion of an African American figure (left) in the frieze encircling the Confederate Monument at Arlington National Cemetery. The monument, funded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and dedicated in 1914, includes around its base a bronze tableau of Confederate soldiers marching off to war, answering their nation’s call. The young black man, wearing a kepi, marches alongside a group of soldiers; the others are armed but the African American carries no visible weapon. Nonetheless, his presence among the soldiers is usually presented as prima facie evidence that African Americans, too, were enlisted as soldiers in the Confederate Army. He’s cited on multiple websites, such as here, here, here, here and here; a web search on the phrases “Black Confederate” and “Arlington” generates several thousand hits. This descripti0n, on the blog of the California Division of the SCV is typical:

One of the oft-cited elements in discussion of Black Confederates is the inclusion of an African American figure (left) in the frieze encircling the Confederate Monument at Arlington National Cemetery. The monument, funded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and dedicated in 1914, includes around its base a bronze tableau of Confederate soldiers marching off to war, answering their nation’s call. The young black man, wearing a kepi, marches alongside a group of soldiers; the others are armed but the African American carries no visible weapon. Nonetheless, his presence among the soldiers is usually presented as prima facie evidence that African Americans, too, were enlisted as soldiers in the Confederate Army. He’s cited on multiple websites, such as here, here, here, here and here; a web search on the phrases “Black Confederate” and “Arlington” generates several thousand hits. This descripti0n, on the blog of the California Division of the SCV is typical:

Black Confederate soldier depicted marching in rank with white Confederate soldiers. This is taken from the Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery. Designed by Moses Ezekiel, a Jewish Confederate, and erected in 1914. Ezekiel depicted the Confederate Army as he himself witnessed. As such, it is perhaps the first monument honoring a black American soldier.

Sounds pretty convincing. Too bad it’s not, you know, true. As James W. Loewen and Edward H. Sebesta point out in their recent anthology, The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader, the booklet published by the United Daughters of the Confederacy at the time of the monument’s dedication gives an entirely different identification. Going back to that original text, it is detailed and explicit:

But our sculptor, who is writing history in bronze, also pictures the South in another attitude, the South as she was in 1861-1865. For decades she had been contending for her constitutional rights, before popular assemblies, in Congress, and in the courts. Here in the forefront of the memorial she is depicted as a beautiful woman, sinking down almost helpless, still holding her shield with “The Constitution” written upon it, the full-panoplied Minerva, the Goddess of War and of Wisdom, compassionately upholding her. In the rear, and beyond the mountains, the Spirits of Avar are blowing their trumpets, turning them in every direction to call the sons and daughters of the South to the aid of their struggling mother. The Furies of War also appear in the background, one with the terrific hair of a Gordon, another in funereal drapery upholding a cinerary urn.

Then the sons and daughters of the South are seen coming from every direction. The manner in which they crowd enthusiastically upon each other is one of the most impressive features of this colossal work. There they come, representing every branch of the service, and in proper garb; soldiers, sailors, sappers and miners, all typified. On the right is a faithful negro body-servant following his young master, Mr. Thomas Nelson Page’s realistic “Marse Chan” over again.

The artist had grown up, like Page, in that embattled old Virginia where “Marse Chan” was so often enacted.

And there is another story told here, illustrating the kindly relations that existed all over the South between the master and the slave — a story that can not be too often repeated to generations in which “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” survives and is still manufacturing false ideas as to the South and slavery in the “fifties.” The astonishing fidelity of the slaves everywhere during the war to the wives and children of those who were absent in the army was convincing proof of the kindly relations between master and slave in the old South. One leading purpose of the U. D. C. is to correct history. Ezekiel is here writing it for them, in characters that will tell their story to generation after generation. Still to the right of the young soldier and his body-servant is an officer, kissing his child in the arms of an old negro “mammy.” Another child holds on to the skirts of “mammy” and is crying, perhaps without knowing why.

My emphasis. “Faithful negro [sic.] body servant” is not a soldier under arms. But it is consistent with the “loyal slave” meme — or “astonishing fidelity,” as the monument’s description calls it — so central to the Lost Cause during those years; similar sentiments appeared on monuments throughout the South.

The comparison to “Marse Chan” further reinforces the theme. “Marse Chan” was a short story by Thomas Nelson Page (1853-1922), that first appeared in Century Magazine in 1884. Nominally set in 1872, “Marse Chan” is told in flashback through the eyes of Sam, a young slave in antebellum Virginia who is assigned as body servant to his master’s son, Tom Channing. Tom grows up and, when the war comes, Sam follows his young master into the army, describing his assignment in the dialect-style of writing commonly used by white authors of the period when writing dialogue for black characters: “an’ I went wid Marse Chan an’ clean he boots, an’ look arfter de tent, an’ tek keer o’ him an’ de hosses.” A contemporary classic of Lost Cause fiction, “Marse Chan” was Page’s best-known work. It would have been familiar to those attending the dedication, who would have understood exactly how its protagonist was the literary parallel of the figure in bronze.

The figure on the monument doesn’t represent a soldier, but it wouldn’t matter much as historical documentation if it did; had the sculptor, Moses Ezekiel, depicted the man explicitly as a soldier, it would reveal only that thought it important to include as part of the story he wanted to present — not necessarily that such men were commonplace. Those claiming the figure as “evidence” of African American soldiers in Confederate ranks a half-century prior to the monument’s unveiling make the common era of assuming that the memorial represents history as it actually was. In fact, no memorial does that; rather, they reflect the story and impressions that their sponsors and artisans want to be remembered, and depict the past in a particular way. Some monuments are more objectively accurate than others, but none is without its bias.

The rush to point to the figure on the Arlington memorial is, sadly, typical of the “scholarship” that informs much of the advocacy for Black Confederates. It reflects a sort of grade-school literalism; there’s a black figure in among the soldiers, therefore this man was a soldier, therefore this is proof of African Americans in the ranks of the Confederate Army more generally. The truth, of course, is not quite so obvious, but revealing it requires taking time to go back to the primary sources and giving some consideration to the context of the time of the monument — 1914, that is, not 1861-65 — and the preferred interpretation of the monument’s sponsors, the UDC. Once you understand those things, and not before, you can start looking for meanings and evidence contained within.

_____________

Additional, October 28: Stan Cohen and Keith Gibson’s Moses Ezekiel: Civil War Soldier, Renowned Sculptor reveals no further information about his design process or his own views on the Confederate Monument at Arlington; it simply repeats the description in the official UDC booklet. Ezekiel also completed statues of Thomas Jefferson for the University of Virginia and of Stonewall Jackson on the parade ground at VMI. It’s beautiful little book, highly recommended.

A Smart Take on Black Confederates

With all due respect to Kevin and Robert and so many others who’ve pulled apart the Black Confederate meme, spread the pieces out on the table and looked at them from different angles to see what makes it run, Adam Serwer today had one of the most insightful, cut-to-the-core, expose-the-man-behind-the-curtain analyses I’ve seen yet:

White guilt is generally characterized as a liberal phenomenon. The idea is that liberals seek to exonerate themselves from past racism rather than simply meet their obligations to their fellow citizens. To the extent that the former is an accurate description of someone’s motives, the criticism is warranted. But the attempt to minimize the suffering caused by slavery and segregation, to recast the Lost Cause as one motivated by “honor” and self-determination rather than racial supremacy and the preservation of chattel slavery, arises out of the same contemptible emotional impulse. The Lost Causer insisting that the Confederacy was not built on racism because of the presence of black soldiers isn’t any less mired in guilt than the liberal quietly mouthing the names of their black friends as they count them on their fingertips. In both cases, the individual trying to free themselves from history ends up drowning in a bottomless pit of self-pity and self-deception that, over time, can only ferment into rage over inability to find an absolution that will be forever beyond their reach.

_____________

h/t, David White of the Golden Horde.

A Hot Mess of Historiography

I haven’t written much here about the new book by Ann DeWitt and Kevin M. Weeks, Entangled in Freedom, a novel for young people. The book’s protagonist, Isaac Green, is a young black slave in Civil War Georgia who follows his master into the Confederate Army and, by virtue of having memorized the Bible, quickly finds himself voted by the white soldiers to be the regimental chaplain. I’ve tried to avoid the subject in part because Levin has been all over it since the book was announced, and partly because I had intended to publish here an e-mail interview with Ms. DeWitt, trying to get at some of her background and thinking in writing and publishing the work. I contacted her a couple of weeks ago asking if she’d be willing, and she promptly responded positively. But I got lazy and didn’t send her my questions and, in the meantime, the debate over the book has intensified considerably. Last month Mr. Weeks sent a copy of the book and an angry letter to Levin’s employer — very bad form, that — accusing Levin of “slander” and trying to have the book “silenced.” In the back-and-forth that’s followed, both on Levin’s site and Ms. DeWitt’s, both sides have laid out their cases (and likely will continue to do so), and I’m not sure that there’s any point now in doing the e-mail interview. I don’t think it will illuminate much, since neither “side” in the debate is even speaking the other’s language.

Here is what I mean about not speaking each other’s language: Levin’s (and others’) criticisms of the book — what’s known of it — revolved entirely around the historicity of it, how well the fictional story fits within the known historical framework of that time and place. In response, Ms. DeWitt counters with a response outlining her values and motivations in writing the book:

Imagine writing a novel for young adults which (1) espouses the sanctity of marriage, (2) does not contain profanity, (3) promotes earning ones way in America, (4) advocates true friendship, (5) demonstrates the positive progression of America over the last 150 years, and (6) highlights the strength of the family unit; yet, the novel is dubbed “nonsense” by a recognized Virginia Civil War journalist and historian.

The above six principles are the family narratives of Ann DeWitt. I have no 19th century written documentation of these six family values because they were passed down to me verbally by my ancestors. I do not secretly hide them but proudly share them with the world.

It’s clear that, far from defending the research and historical background presented in the novel, she doesn’t understand the criticism of it. None of those “principles” have anything to do with the historical accuracy of the setting or the plot. One could write such a work in any of a thousand settings, and and frame it in a way that is, if not historically documented, at least plausible. Laura Ingalls Wilder is the obvious example of doing this, although she had the advantage of having actually lived the life she described in her writing.

DeWitt asserts that “these six family values because they were passed down to me verbally by my ancestors.” Okay, fine, but no one’s asking for documentation of her family values. This statement reveals something much more essential here, specifically that, in Ms. DeWitt’s view, criticizing the historical accuracy of the book is criticizing her family, and her values. She sees it not as criticism of her work, but as a personal attack on her. It’s not the same thing at all. I don’t doubt that Ms. DeWitt is a very well-intentioned and sincere person, but having good intentions and a strong moral compass is not enough when it comes to presenting a believable and realistic picture of the past.

Ms. DeWitt and Mr. Weeks haven’t written an historical novel; they’ve written a moral allegory nominally set in the Civil War. But it’s not the South that existed in 1860s or, for that matter, the 1960s. Ms. DeWitt and Mr. Weeks have constructed a Confederacy where wise people “in the Deep South knew all the time that black people are cut from the same board of cloth as whites,” and “knew that slavery wasn’t going to last always.” Alexander Stephens and George Wallace never existed in this version of the American South. Ms. DeWitt and Mr. Weeks have the notion of historical fiction exactly backwards; the goal is to tell a story that fits within the larger, factual context of its setting, not to create a fictional history that supports the particular story one wants to tell for other reasons.

The passage Levin posted recently shows that the historical framework for the novel is based largely on Black Confederate factoids and memes culled from the web. Just that one short passage — 648 words — crams in multiple Black Confederate bullet points, strung together by stilted dialogue. Only a tiny percentage of Confederate soldiers owned slaves? Check. Harper’s Weekly reference to black soldiers at Manassas? Check. Loyal slaves will be delivered “a great prize?” Check. Slaves and owners who “get along fine?” Check.

In defending her book and its thesis, Ms. DeWitt has made some extremely odd arguments — so odd or tangential that one might guess that they were meant in jest, though I don’t think they were. She argues — in all sincerity, it seems — that the slaves who went to war with their masters as body servants were the historical equivalent of present-day, college-educated executive assistant, and then extends that analogy further to the entourage that a modern-day U.S. president travels with. She openly wonders why “mark-and-capture,” a technique used to estimate wildlife populations that involves trapping animals, tagging them and releasing them back into the wild to be recaptured and counted at a later date, hasn’t been used to calculate the numbers of Black Confederates. DeWitt does an online search of Confederate pension records from Alabama’s state archives under the surname “Slave” (!), but says cryptically that the archive “does not document if these African-Americans fought for the Union or the Confederate States Army.” DeWitt lists over two hundred men who received “colored” pensions from the State of Tennessee, helpfully adding that “Colored = Black = African-American,” but omits the fact that Tennessee differentiated these from “S” pensions, issued to soldiers. She hints — both on her website and in the novel — that enlistment or service records that do not explicitly identify the subject as white should be taken as de facto evidence of prospective Black Confederates: “CSA enlistment forms and pension applications did not include race, so . . . the world may never know the total number of African-Americans (Blacks) who served in any and all capacities of the American Civil War.” And then there are explanations that are just odd non-sequiturs:

African-Americans want to know their family history for personal as well as medical reasons. We have turned to scientific DNA testing in order to trace our family lineage. As a human being, it is offensive when historians overall imply that my ancestors in South Carolina were not smart enough to band together and run across a field of dying Confederate soldiers to join the Union Army.

As historiography, this is a hot mess. I don’t know Ms. DeWitt; she seems like a very nice, well-intentioned person who’s deeply devoted to her family and its traditions. That’s a good thing, but I fear that she assumes oral tradition, passed from generation to generation, to be sufficient in not only interpreting her own family’s history — I’ve addressed this before with regard to my own Confederate ancestors — but also in understanding the South, the Confederacy and the fundamental nature of the white supremacist slave society the Confederacy was established to protect and promote. The historical world she presents in Entangled in Freedom isn’t based on research or academic study; it’s the product of intuition and her own, deeply-held faith. But those things are not enough, and to frame what’s intended as an uplifting and inspiring personal story within such a farcical historical context does a real disservice to the public generally, and to students particularly.

It’s a missed opportunity.

Now We’re Finally Getting Somewhere.

Over the last few weeks there’s been a good bit of discussion about Ann DeWitt and her website on Black Confederates, particularly since the announcement of a new novel for young adults, written by her and Kevin M. Weeks, Entangled in Freedom. The discussion has been pretty volatile over at Levin’s place — who coulda’ seen that coming? — but I’ve tried to steer a little clear of criticizing Ms. DeWitt personally, because she seems a sincere, if ill-informed, advocate for the idea, and because at this point anything else will be perceived as “piling on.” But now, I think, she’s actually (and unwittingly) done us all a favor, by acknowledging explicitly what skeptics have been saying for a long time: that at the core of Black Confederate lies a definition of the word “soldier” that is so broad, so vague and nebulous that the word can be taken to mean virtually anything, and is applied to any person who had even the remotest connection to the Confederate army.

This morning, I noticed her project home page now opens with a definition:

Merriam Webster Dictionary defines a soldier as a militant leader, follower, or worker.

If we’re going to quote the dictionary, let’s be clear: she’s quoting the secondary, alternate definition. By citing it, Ms. DeWitt tacitly acknowledges that the primary definition of the word — “a: one engaged in military service and especially in the army b : an enlisted man or woman c : a skilled warrior” — does not generally apply, or is at least too narrow to describe, Black Confederates as she identifies them. It is not too much to say, I think, that in citing such a broad definition, Ms. DeWitt just knocked over the whole house of cards that comprises most of the “evidence” for Black Confederates.

There’s an old saying that a “gaffe” is what happens when a politician accidentally speaks the truth. This is a gaffe. This is the truth that forms the foundation of most Black Confederate advocacy. To qualify as a Black Confederate, one needs only to qualify as a follower or a worker. In short, the term “soldier” applies to anyone — enlisted man, musician, teamster, body servant, cook, hospital orderly, laundress, sutler, drover, laborer, anyone — involved with the army in any capacity.

A long time ago, I learned a rule that has stood me in good stead ever since: any time a writer or public speaker starts off his or her essay by quoting a definition from the dictionary, you can safely stop reading or listening, because nothing worthwhile or new is likely to follow. That’s still true, but it this case Ms. DeWitt’s use of the technique does do us all a genuine service, by admitting what Black Confederate skeptics have been saying all along — that the movement’s advocates are so loose with the their definitions, so willing to conflate service as a volunteer, enlisted soldier under arms with a slave’s compelled service as a cook and body servant to his owner and master, that the narratives they offer cannot stand close historiographical scrutiny at all. To borrow an analogy allegedly coined by Lincoln himself, Black Confederate advocacy is like shoveling fleas across the barnyard — you start with what seems to be a shovelful, but by the time you get to the other side, there’s very little actually there.

Update, August 22: I just noticed this on the website, as well:

Another challenge is the fact that 19th century CSA enlistment forms and pension applications did not include race, so unless all current SCV members come forward with more historical accounts, the world may never know the total number of African-Americans (Blacks) who served in any and all capacities of the American Civil War.

If I’m reading this correctly, Ms. DeWitt views any Confederate enlistment or pension document that doesn’t explicitly state otherwise to be potential evidence of a Black Confederate. Wowza!

Not sure what the call for “all current SCV members come forward with more historical accounts” means.

5 comments