In the Field with the Golden Horde

As some of you know, I spent last week blogging about the Civil War over at Ta-Nehisi Coates’ place at The Atlantic. It was a huge honor to be asked, and it’s gratifying that my efforts have been generally well received. That’s a vocal, well-read and scary-smart crowd over there, and they don’t suffer fools. You can read some of my longer posts here:

- Small Truth Papering Over a Big Lie — fisking the myth that very few Confederate soldiers had any connection to the institution of slavery.

- Susie King Taylor — on the autobiography of a slave girl who learned to read and write in Savannah, and went on to found schools in post-Civil War Georgia

- ‘We Have Received Provocation Enough’ — an expansion of my earlier piece on the seizure of slaves during the Gettysburg campaign

- Arlington, Bobby Lee, and the ‘Peculiar Institution’ — looking at the evidence presented in Elizabeth Brown Pryor’s masterful Reading the Man for Lee’s views on slavery.

Yep, there’s a theme there. Didn’t plan it that way. When TNC invited me to blog, I started thinking about Civil War topics that had been discussed on the blog before, that I thought hadn’t been fully explored, or that I thought I could address in a meaningful way. I also wanted to push back explicitly against some of what I believe are some of the more pernicious misunderstandings and myths about the war, just as I have tried to do here at Dead Confederates. Many of these revolve around the institution of slavery, and its complete infusion into all aspects of the South in the antebellum period, including the Confederate military and its leaders. My intent was to use the opportunity of guest-blogging at The Atlantic to say some things that, in my view, needed to be said. And I’m very grateful for the having been given the opportunity to do so.

Image: “The pursuit of Gen. Lee’s rebel army. The heavy guns – 30 pounders – going to the front during a rain storm.” Library of Congress. I like this drawing for several reasons. First, it’s a relatively unusual depiction of soldiers on the march; most contemporary drawing either show soldiers in battle or in camp. Second, it shows soldiers in miserable weather, a driving rainstorm — note the reflections in the wet, muddy ground and the wind-whipped trees. (The soldiers look pretty damn miserable to me.) Third, it shows heavy artillery configured for transport, including having the gun tube shifted back on the carriage to provide a more stable center-of-gravity. All in all, it’s highly unusual image that depicts an all-too-common scene familiar to soldiers in both gray and blue.

That Was Nice to See

Had a great, if much too short, trip to Austin this weekend, and got to do some of the things I’ve come to enjoy there — breakfast at Star Seeds Cafe, browsing at the best toy store ever, and seeing some old (but never old) friends. I even found my new favorite place for Mongolian Beef. But I think the highlight was late Saturday afternoon, when I get to see for myself that that rancid old klansman’s name is gone — note the bare pole at right — from what is now officially termed Creekside Residence Hall.

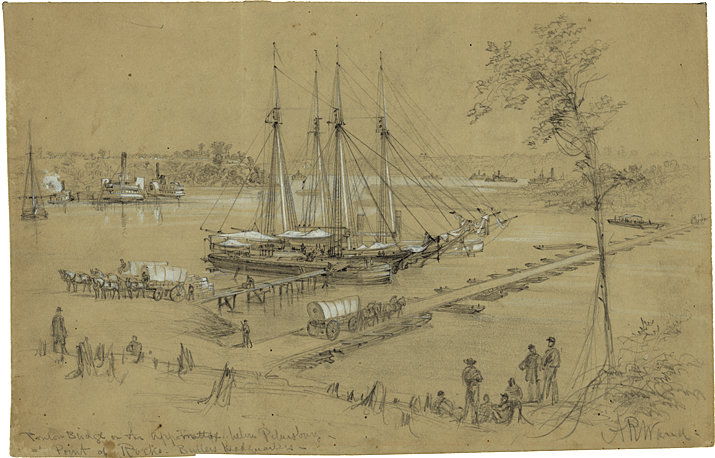

Pontoon Bridge, Petersburg

A. R. Waud, “Ponton [sic.] Bridge on the Appomattox below Petersburg–Point of Rocks–Butler’s headquarters.” Library of Congress. Original here.

A Secessionist Surcharge?

So over the weekend I picked up a second-hand set of Wiley’s Billy Yank and Johnny Reb. Classic works, ought to be on every CW reference shelf, yadayadayada. Johnny Reb was priced $2 more than Billy Yank, but I initially attributed that to inattention at the shop. No, turns out that the original list price had Johnny Reb $3 higher than its mate, $14.95 to $11.95. And even now on Amazon — which sells them in paperback for the same price, $17.12, the hardback list price for Johnny Reb is $1.60 more than Billy Yank. I have no idea why. There should be no significant difference in actual production cost; both books are almost exactly the same length, and have similar numbers of images. I’m guessing the pricing reflects either (a) a slightly stronger sales market for works about Confederate soldiers than Union, or (b) it’s yet another example of liberal, academic-type Yankee publishers wielding an economic cudgel to oppress God-fearing, hard-working, patriotic Southrons.

So over the weekend I picked up a second-hand set of Wiley’s Billy Yank and Johnny Reb. Classic works, ought to be on every CW reference shelf, yadayadayada. Johnny Reb was priced $2 more than Billy Yank, but I initially attributed that to inattention at the shop. No, turns out that the original list price had Johnny Reb $3 higher than its mate, $14.95 to $11.95. And even now on Amazon — which sells them in paperback for the same price, $17.12, the hardback list price for Johnny Reb is $1.60 more than Billy Yank. I have no idea why. There should be no significant difference in actual production cost; both books are almost exactly the same length, and have similar numbers of images. I’m guessing the pricing reflects either (a) a slightly stronger sales market for works about Confederate soldiers than Union, or (b) it’s yet another example of liberal, academic-type Yankee publishers wielding an economic cudgel to oppress God-fearing, hard-working, patriotic Southrons.

How Val Giles Made Second Sergeant

West slope of the Little Round Top, Gettysburg, as seen from the plain along Plum Run. This is the view that presented itself to the 4th and 5th Texas Regiments late on the afternoon of July 2, 1863. Photo by jwolf312, used under Creative Commons License.

Valerius Cincinnatus Giles — inevitably known simply as “Val” — was a twenty-one-year-old soldier in Company B of the 4th Texas Infantry when that unit made its famous, unsuccessful assault on the Federal positions on Little Round Top, late on the second day during the Battle of Gettysburg. In his later years, Giles spent much of his free time compiling a memoir, but did not live to see its completion. Giles died in 1915; his writings, edited by Mary Lasswell, were finally published in 1961. That volume, Rags and Hope, has since become a classic first-person account of Texas soldiers during the war.

It was nearly five o’clock when we began the assault against the enemy that was strongly fortified behind logs and stones on the crest of a steep mountain. It was more than half a mile from our starting point to the edge of the timber at the base of the ridge, comparatively open ground all the way. We started off at quick time, the officers keeping the column in pretty good line until we passed through a blossoming peach orchard and reached the level ground beyond. We were now about 400 yards from the timber. The fire from the enemy, both artillery and musketry, was fearful.

In making that long charge, our brigade got jammed. Regiments lapped over each other, and when we reached the woods and climbed the mountains as far as we could go, we were a badly mixed crowd.

Confusion reigned everywhere. Nearly all our field officers were gone. Hood, our Major General, had been shot from his horse. He lost an arm from the wound [sic.]. Robertson, our Brigadier, had been carried from the field. Colonel Powell of the Fifth Texas was riddled with bullets. Colonel Van Manning of the Third Arkansas was disabled. and Colonel B. F. Carter of my Regiment lay dying at the foot of the mountain.

The side of the mountain was heavily timbered and covered with great boulders that had tumbled from the cliffs above years before. These afforded great protection to the men.

Every tree, rock and stump that gave any protection from the rain of Minié balls that were poured down upon us from the crest above us, was soon appropriated. John Griffith and myself pre-empted a moss-covered old boulder about the size of a 500-pound cotton bale.

By this time order and discipline were gone. Every fellow was his own general. Private soldiers gave commands as loud as the officers. Nobody paid any attention to either. To add to this confusion, our artillery on the hill to our rear was cutting its fuse too short. Their shells were bursting behind us, in the treetops, over our heads, and all around us.

Nothing demoralizes troops quicker than to be fired into by their friends. I saw it occur twice during the war. The first time we ran, but at Gettysburg we couldn’t.

This mistake was soon corrected and the shells burst high on the mountain or went over it.

Major Rogers, then in command of the Fifth Texas Regiment, mounted an old log near my boulder and began a Fourth of July speech. He was a little ahead of time, for that was about six thirty on the evening of July 2d.

Of course nobody was paying any attention to the oration as he appealed to the men to “stand fast.” He and Captain Cousins of the Fourth Alabama were the only two men I saw standing. The balance of us had settled down behind rocks, logs, and trees. While the speech was going on, John Haggerty, one of Hood’s couriers, then acting for General Law, dashed up the side of the mountain, saluted the Major and said: “General Law presents his compliments, and says hold this place at all hazards.” The Major checked up, glared down at Haggerty from his’ perch, and shouted: “Compliments, hell! Who wants any compliments in such a damned place as this? Go back and ask General Law if he expects me to hold the world in check with the Fifth Texas Regiment!”

The Major evidently thought he had his own regiment with him, but in fact there were men from every regiment in the Texas Brigade all around him.

From behind my boulder I saw a ragged line of battle strung out along the side of Cemetery Ridge and in front of Little Round Top. Night began settling around us, but the carnage went on.

There seemed to be a viciousness in the very air we breathed. Things had gone wrong all the day, and now pandemonium came with the darkness.

Alexander Dumas says the devil gets in a man seven times a day, and if the average is not over seven times, he is almost a saint.

At Gettysburg that night, it was about seven devils to each man. Officers were cross to the men, and the men were equally cross to the officers. It was the same way with our enemies. We could hear the Yankee officer on the crest of the ridge in front of us cursing the men by platoons, and the men telling him to go to a country not very far away from us just at that time. If that old Satanic dragon has ever been on earth since he offered our Saviour the world if He would serve him, he was certainly at Gettysburg that night.

Every characteristic of the human race was presented there, the cruelty of the Turk, the courage of the Greek, the endurance of the Arab, the dash of the Cossack, the fearlessness of the Bashibazouk, the ignorance of the Zulu, the cunning of the Comanche, the recklessness of the American volunteer, and the wickedness of the devil thrown in to make the thing complete.

The advance lines of the two armies in many places were not more than fifty yards apart. Everything was on the shoot. No favors asked, and none offered.

My gun was so dirty that the ramrod hung in the barrel, and 1 could neither get it down nor out. 1 slammed the rod against a rock a few times, and drove home ramrod, cartridge and all, laid the gun on a boulder, elevated the muzzle, ducked my head, hollered “Look out!” and pulled the trigger. She roared like a young cannon and flew over my boulder, the barrel striking John Griffith a smart whack on the left ear. John roared too, and abused me like a pickpocket for my carelessness. It was no trouble to get another gun there. The mountain side was covered with them.

Just to our left was a little fellow from the Third Arkansas Regiment. He was comfortably located behind a big stump, loading and firing as fast as he could. Between biting cartridges and taking aim, he was singing at the top of his voice: “Now let the wide world wag as it will, I’ll be gay and happy still”

The world was wagging all right-no mistake about that, but 1 failed to see where the “gay and happy” came in. That was a fearful night. There was no sweet music. The “tooters” had left the shooters to fight it out, and taken “Home, Sweet Home” and “The Girl I Left Behind Me” with them.

Our spiritual advisers, chaplains of regiments, were in the rear, caring for the wounded and dying soldiers. With seven devils to each man, it was no place for a preacher, anyhow. A little red paint and a few eagle feathers were all that was necessary to make that crowd on both sides into the most veritable savages on earth. White-winged peace didn’t roost at Little Round Top that nightl There was not a man there that cared a snap for the golden rule, or that could have remembered one line of the Lord’s Prayer. Both sides were whipped, and all were furious about it.

We lay along the side of Cemetery Ridge, and on the crest of the mountain lay 10,000 Yankee infantry, not 100 yards above us. That was on the morning of July 3, 1863, the day that General Pickett made his gallant, but fatal charge on our left.

Our Corps, Longstreet’s, had made the assault on Cemetery Ridge and Little Round Top the evening before. The Texas Brigade had butted up against a perpendicular wall of gray limestone. There we lay on the night of the 2d with the devil in command of both armies. About daylight on the morning of the 3rd old Uncle John Price (colored) brought in the rations for Company B. There were only fourteen of us present that morning under the command of Lieutenant James T. McLaurin.

I felt pretty safe behind my big rock; every member of the regiment had sought protection from the storm of Minié balls behind rocks or trees. The side of the mountain was covered with both. When Uncle John brought in the grub, he deposited it by a big Hat rock, lay down behind another boulder, and went to sleep.

Sergeant Mose Norris and Sergeant Perry Grumbles had been killed in our charge the evening before, and Sergeant Garland Colvin was wounded and missing.

Somebody had to issue the grub to the men, and as an incentive to induce me to take the job, the Lieutenant raised me three points. He too was located in a bombproof position behind another big boulder just in front of me.

“Giles,” he said, “Sergeant Norris always issued the rations to the men, but poor Mose is dead now and you must take his place. I appoint you Second Sergeant of Company B. Divide the rations into fourteen equal parts and have the men crawl up and get them.”

Every time a fellow showed himself, some smart aleck of a Yankee on top of the ridge took a shot at him. I didn’t even thank the Lieutenant for the honor (or better, the lemon) that he handed me, and must admit that I undertook the job with a great deal of reluctance.

A steady artillery fire was going on all along the line and a sulphuric kind of odor filled the air, caused by the great amount of black powder burned in the battle. Maybe it was the fumes of old Satan as he pulled out that morning leaving the row to be settled by Lee and Meade. We were comparatively safe from the big guns, but it was the infantry just above us that made things unpleasant. I crawled up to the camp kettle of boiled roasting ears and meal-sack full of ironclad biscuits that Uncle John had brought in, and began dividing the grub and laying it on top of a big flat rock.

The Yanks on the hill became somewhat quiet, so I got a little bolder and popped my head above the rock. They saw my oId black wool hat and before you could say “scat,” two Minié balls flattened out on top of the rock, making lead prints half as big as a saucer, and smashing two rations of grub. One roasting ear was cut in two, but the old cold-water ironclad biscuits went rolling down the hill, solid as the rock from which they flew.

Cuss words don’t look well in print, but I don’t see how a fellow can tell his personal experience in the army without letting one slip in now and then. In this case I’ll let it pass!

When those bullets struck the lunch counter, the newly-made Second Sergeant disappeared from view. The remark he made caused that grim old Lieutenant to laugh and say, “Let the boys crawl up and help themselves.” The range was so close that when those bullets struck the solid rock, it flew all to pieces, a small fragment striking me on the upper lip, drawing a few drops of blood and mussing up my baby mustache.

Second Sergeant was my limit in the Fourth Texas Regiment.

I Was Praying for Intermission, Myself

It doesn’t really bother me so much that the 2003 film Gods and Generals portrays Stonewall Jackson as a bit of a hyper-religious crank because, you know, he was.

What bothers me is that the film portrays this as a good thing.

Would Crock Davis be Considered a “Black Confederate?”

Crock Davis (c.) and Eighth Texas Cavalry veterans, San Marcos, Texas, October 29, 1913. From the Online Archive of Terry’s Texas Rangers.

One of the hotter debates in Civil War circles today is the existence of “Black Confederates,” African-American men who (it is claimed) took up arms and served as soldiers in the Southern armies. There’s little discussion of this among professional historians, who for years have looked for contemporary, primary-source documents to confirm the enlisted service of specific individuals, only to find none. On the other side of the question are Confederate heritage groups and individuals who pull together bits and fragments of pension records, newspaper accounts, oral history and outright fakery to make a claim that this man or that one served in the ranks as a soldier. While there are many reasons why and individual might take up such a claim, and a great many of them are sincere and well-intentioned (if poorly informed when it comes to historical methods), it seems very obvious that for the heritage groups pushing the idea (including but not limited to the SCV), it’s part of a larger effort to distance themselves and the Confederate ancestors they venerate from the institution of slavery, and the moral implication that goes with it. What better way to show that the Confederacy was not really about slavery, than to show that hundreds (Thousands? Tens of thousands?) of African American men willingly and voluntarily took up arms in defense of the Confederacy. The Black Confederate is nothing more than the “faithful slave” meme so central, so essential, to the Lost Cause, made more palatable for modern audiences.

No one who has more than a grade-school understanding of the Civil War has ever suggested that the Southern armies were not surrounded by African American men and women. They performed in all manner of roles, as common laborers digging trenches and setting up fortifications. The served as teamsters. They worked in all manner of service jobs, as cooks and launderers and personal “body servants.” The vast, vast majority of these men were slaves, who had no say whatsoever as to where they were to go or what they did. No one who has looked seriously at this conflict denies that African Americans were — mostly unwillingly — a central part of the Confederacy’s war effort.

The difficulty is that individuals and groups are making claims of these men having been soldiers, on little or no direct and contemporary evidence. No one questions that these men went off to war, but like the tens of thousands civilian contractors in Iraq and Afghanistan today, they were not soldiers, even though they “served” (in the broadest sense) in a combat zone. It’s really tricky trying to determine the roles of specific African-Americans who went to war with Southern troops, and given the lack of records, easy to ascribe to them status as soldiers that did not, in fact, apply. Time and again, in those cases where documentation is available, the claim that these men were recognized at the time — or even decades later — as soldiers falls apart.

In many cases, the “evidence” presented for Black Confederates consists of photos of elderly African American men, sometimes in uniform, participating in veterans’ reunions or other commemorations decades after the war ended. These are usually offered without detailed elaboration of these men’s individual histories, or even with identification of them by name. (The practice of posting unidentified photos, not coincidentally, makes it impossible for anyone else to independently check the validity of the claims now being made on their behalf.) The assumption seems to be that, if these men participated in commemorative events all those years later, that in and of itself confirms that they served as soldiers in the war. That’s not true, and the case of Crock Davis gives a good example of how complex these men’s involvement with Confederate veterans’ groups can be.

Recently I was digging through the website for the Eighth Texas Cavalry (Terry’s Rangers), and noticed that in two photos of early 20th century reunions (1905 in Austin and 1913 in San Marcos), there are African American men present in the group. One of these men is Crockett Davis. While (as far as I know) no one has explicitly claimed Davis had been a soldier in that unit, it would be very easy to do so, based on his presence at at least two Ranger reunions. I suspect that much of what is claimed as “evidence”of Black Confederates is based on nothing more than exactly this sort of fragmentary bits of information.

The Ranger reunions were well-covered in the regional press, and the 1913 meeting in San Marcos got extended write-ups in my local paper, on October 29 and 30, 1913. The October 29 story listed him and his hometown among the attendees, as “Crock Davis (colored), Smithville.” That, along with the photo, could easily be taken as evidence of Davis’ having been a trooper in the Rangers. But the next day’s article, tells a more complex story, both about Davis’ wartime service and his status within the Ranger veteran’s group (and with apologies for the contemporary language):

An interested and quiet spectator at all sessions has been an old time “before-the-war” darkey, Crockett Hill, of Smithville, known to all the rangers as “Uncle Crock.” His curly hair is whitened with the years, but he steps briskly and tells with pride that he went all through the war with the rangers as cook and body servant of D. O. and Tom Hill of Smithvllle, and that he never missed a reunion. In the banquet he was not overlooked, but served at a side table along with “his white folks.”

This short paragraph really tells the story. There are three distinct elements here that clearly define both Davis’ wartime status, and his position within the veterans’ group a half-century later.

First, this profile lists Davis’ surname as Hill, the name of his former masters. This was not the name he gave reporters the day before, nor is it the name he went by in his day-to-day life as recorded on multiple census rolls as far back as 1880. But at the Terry’s Rangers reunion — at the meeting where his former master was elected president of the organization — when he’s described by others he’s identified as Crock Hill.

Second, Davis’ wartime role as “cook and body servant” is explicitly defined. There is no suggestion of Davis being recognized as an Eighth Texas trooper. There is no mention (by Davis or anyone else) that he ever took up arms in combat.

Third (and most telling to me), is the note that Davis was an “interested and quiet spectator” at the meeting — showing pretty clearly that he took no active part in the business of the organization. Further, at the veterans’ banquet that evening, he was seated at a side table apart from the white veterans. It’s excruciatingly clear that even fifty years on, the old Confederates did not accept Davis to be a veteran of the same status as they themselves, even though he “went all through the war with the rangers.” (The Hill Brothers were active in the veterans’ group, one of them being elected president at the same meeting. It seems a fair question whether Davis would have been as welcomed at the ranger reunions had the brothers not been present.) Crock Davis was no more considered a trooper of the Eighth Texas Cavalry in 1913 than he had been a half-century before.

My point here is not to suggest that the white veterans of Terry’s Rangers still thought of Davis as a slave, or that he was compelled to attend multiple reunions. I’m certain that there was a real sense of affection and bonhomie on both sides. But it’s equally certain that even after fifty years, there remained an unbridgeable gap between the old men.

To be sure, the Terry’s Rangers website makes no explicit claim that Davis — whom they list as “Hill” — was a soldier during the war, only that he was a member of the veterans’ association. I cannot confirm that he was actually a member, only that he attended the meetings. But it would be very easy for someone to claim that Davis was a Black Confederate, although a little diligent research — say, about an hour’s worth, using entirely online resources — would definitively disprove such a claim. I wonder how many African American men now being identified as Confederate soldiers are like Crock Davis — men who went to war as slaves, and even fifty years later were still not accepted by their fellows as peers.

Encounters with Grant at Chattanooga

Grant (l.) and his staff on Lookout Mountain, near Chattanooga, Tennessee, November 1863. Library of Congress photo.

One of the great firsthand accounts of Texas troops in the Civil War is Val C. Giles’ Rags and Hope: Four Years with Hood’s Brigade, Fourth Texas Infantry, 1861-1865 (Mary Lasswell, ed.). The account of Sergeant Valerius Cincinnatus Giles is important to me personally because he served in the same regiment, the Fourth Texas, as one of my relatives. More significant still, Giles’ time is the unit matches my uncle’s almost exactly, from the formation of the unit to each man’s being taken prisoner during the Chattanooga campaign — Giles in late October 1863; my uncle about three weeks later. It seems likely that much of what Giles saw and did and heard was shared by other men in the regiment, including my relative.

Giles was captured during a confused skirmish in the early morning hours of October 29. After running smack into a big, burly German private of the 136th New York in the dark, Giles and about twenty of his comrades were rounded up and marched back behind Union lines.

We were marched back and halted near General Hooker’s headquarters. By that time it was daylight, and the whole earth appeared covered with bluecoats. I was a Sergeant at that time, and the only noncommissioned officer in our squad. I was ordered to report to General Hooker, and was escorted to headquarters, between two muskets. Hooker was rather a pleasant-looking man, and returned my salute like a soldier. Then he began to interrogate me. He asked me a hundred questions and wound up by saying that I was the most complete know-nothing for my size he had ever seen.

That evening we started to Chattanooga under a heavy guard. We crossed the Tennessee River about four miles below Lookout Mountain. Near the middle of the bridge we were halted and formed in one rank on each side, to let some General Officers and their escorts pass. General Grant and General Thomas rode in front, followed by along train of staff officers and couriers. When General Grant reached the line of ragged, filthy, bloody, starveling, despairing prisoners strung out on each side of the bridge, he lifted his hat hat and held it over his head until he passed the last man of that living funeral cortege. He was the only officer in that whole train who recognized us as being on the face of the earth. Grant alone paid military honor to a fallen foe.

Grant doesn’t mention this encounter with Giles and his fellows in his memoirs, but he does mention encountering Confederate troops in the field, apparently that same day:

In securing possession of Lookout Valley, Smith lost one man killed and four or five wounded. The enemy lost most of his pickets at the ferry, captured. In the night engagement of the 28th-9th Hooker lost 416 killed and wounded. I never knew the loss of the enemy, but our troops buried over one hundred and fifty of his dead and captured more than a hundred.

After we had secured the opening of a line over which to bring our supplies to the army, I made a personal inspection to see the situation of the pickets of the two armies. As I have stated, Chattanooga Creek comes down the centre of the valley to within a mile or such a matter of the town of Chattanooga, then bears off westerly, then north-westerly, and enters the Tennessee River at the foot of Lookout Mountain. This creek, from its mouth up to where it bears off west, lay between the two lines of pickets, and the guards of both armies drew their water from the same stream. As I would be under short-range fire and in an open country, I took nobody with me, except, I believe, a bugler, who stayed some distance to the rear. I rode from our right around to our left. When I came to the camp of the picket guard of our side, I heard the call, “Turn out the guard for the commanding general.” I replied, “Never mind the guard,” and they were dismissed and went back to their tents. Just back of these, and about equally distant from the creek, were the guards of the Confederate pickets. The sentinel on their post called out in like manner, “Turn out the guard for the commanding general,” and, I believe, added, “General Grant.” Their line in a moment front-faced to the north, facing me, and gave a salute, which I returned.

The most friendly relations seemed to exist between the pickets of the two armies. At one place there was a tree which had fallen across the stream, and which was used by the soldiers of both armies in drawing water for their camps. General Longstreet’s corps was stationed there at the time, and wore blue of a little different shade from our uniform. Seeing a soldier in blue on this log, I rode up to him, commenced conversing with him, and asked whose corps he belonged to. He was very polite, and, touching his hat to me, said he belonged to General Longstreet’s corps. I asked him a few questions—but not with a view of gaining any particular information—all of which he answered, and I rode off.

1 comment