A New Season of Who Do You Think You Are?

My teevee viewing for a long time since has been mostly restricted to current events and, as the general election season gets closer, political news. Regular entertainment television is not usually part of my schedule, but I’ve taken a shine to NBC’s Who Do You Think You Are?, a series that takes celebrities and goes digging for stories of their ancestors. (It’s apparently an adaptation of a British series.) Camera crews follow the celebrities around to different parts of the country and overseas to meet with various genealogists, historians and archivists who help them along in their discovery. The show has done several episodes that had a particular Civil War focus, profiling Matthew Broderick and Spike Lee, but there are other stories that are interesting, as well. Kim Cattrall, for example, uncovered some family secrets that were difficult to learn, but that she found important to know.

The third season of the show began last Friday with Martin Sheen, whose birth name is Ramón Antonio Gerardo Estévez. Sheen is probably known as much for his political activism as for his acting career. The Sheen episode focuses primarily on two uncles who, in the first half of the 20th century, fought in civil wars in their home countries. Sheen’s parents were both immigrants to the United States, his mother from Ireland and his father from Spain. His mother’s elder brother, Michael Phelan, fought in the Irish Civil War in the early 1920s for the Irish Republican Army against the National (or “Provisional”) government, headed by Michael Collins. His Galician father’s brother, Matias Estévez (right, with his family), fought for the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War against the fascists under Franco. Both men found themselves on the losing side of their respective wars, and both ended up imprisoned by their fellow countrymen. There’s an even more remarkable discovery farther back in Sheen’s family tree, but you’ll just have to watch the episode for that.

The third season of the show began last Friday with Martin Sheen, whose birth name is Ramón Antonio Gerardo Estévez. Sheen is probably known as much for his political activism as for his acting career. The Sheen episode focuses primarily on two uncles who, in the first half of the 20th century, fought in civil wars in their home countries. Sheen’s parents were both immigrants to the United States, his mother from Ireland and his father from Spain. His mother’s elder brother, Michael Phelan, fought in the Irish Civil War in the early 1920s for the Irish Republican Army against the National (or “Provisional”) government, headed by Michael Collins. His Galician father’s brother, Matias Estévez (right, with his family), fought for the Republicans during the Spanish Civil War against the fascists under Franco. Both men found themselves on the losing side of their respective wars, and both ended up imprisoned by their fellow countrymen. There’s an even more remarkable discovery farther back in Sheen’s family tree, but you’ll just have to watch the episode for that.

One of the things I thought about while watching Sheen’s episode was that, while he felt an obvious natural affinity to those two men, each of whom had taken up arms for a political cause, and found themselves imprisoned for it (in Matias Estevez’ case, for years), there was no indication that Sheen saw their causes as explicitly his cause. There was no suggestion that Martin Sheen saw himself, personally, as obligated to carry on the fight against the current government of the Republic of Ireland, or go go on a loud, chest-thumping rant about Franco’s fascists. (Possibly because he’s still dead.) It seemed very different than the way some people view the legacy of their ancestors in this country, who fought through a much older conflict, now long past any living memory.

There are some things I don’t much like about Who Do You Think You Are?, all of which are probably due to the necessity of condensing complex stories into a 40- or 45-minute package of entertainment. They compress what would normally be months or years of research by an individual to an improbably short period of time. They use historians and archivists with access to records that, while presumably available to the public, are often obscure and not really accessible to non-specialists. They ignore the dead ends and false leads that are bane of any genealogical researcher. They sometimes take what I think of as a “maybe” finding and present it as an established fact. And inevitably, they tend to zero in on the ancestors who seem to have the most entertaining story, or the most relevance to the modern day celebrity, rather than the more mundane folks who much make up the bulk of that person’s tree.

But what the show does right, I think, makes up for those flaws. It makes the point rather well that prior generations lived lives as complex and difficult — often much more difficult — than our own. It conveys the notion that their stories need to be told, too. It makes doing that historical seem easy (much easier than it often is), and undoubtedly inspires a lot of people to try their hands at it. And that seems to me to be a worthwhile thing.

_____________

Discovering the Civil War at the Houston Museum of Natural Science

The Discovering the Civil War exhibition at its previous venue, the Henry Ford Museum. Via here.

On Saturday the fam and I took the afternoon to visit the exhibition, Discovering the Civil War, currently at the Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS). The exhibit runs through April 29, and is produced by the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration and the Foundation for the National Archives. It’s hard to do a compelling museum exhibition based almost entirely on documents and images; people want to see stuff, and that’s understandable. This particular exhibit succeeds pretty well, I think, in part because the documents they’ve included are genuinely compelling, and do a very good job of telling the story. The exhibition includes, for example, facsimiles of the 1861 Corwin Amendment, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the original text of the 13th Amendment ending slavery in the United States, bearing the signatures of Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax, Vice President and President of the Senate Hannibal Hamlin, and President Lincoln. (The original holograph copy of the Emancipation Proclamation will be on exhibit on February 16-21.)

One of the common complaints among Southron Heritage™ folks is that the limitations of the Emancipation Proclamation “isn’t taught in school” or “you never hear about that” or some such. So I almost laughed out loud when, not a minute after stepping into the first section of the exhibit, an HMNS guide stepped up to explain to us and others some of the featured documents in the show, and drawing very careful distinctions between the limited, wartime scope of the EP, and the permanent, legislative accomplishment of the 13th Amendment.

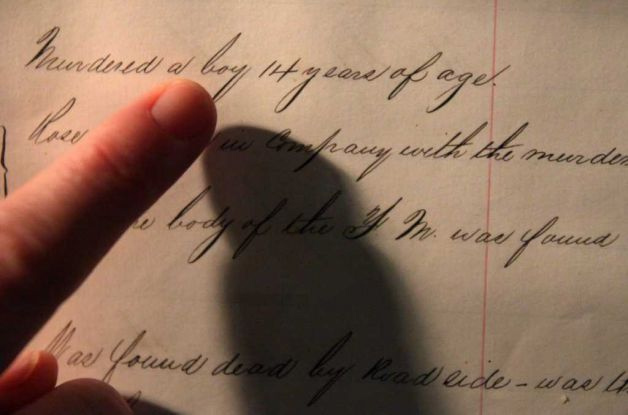

A curator at the Houston Museum of Natural Science points to entries in the Freedmen’s Bureau “Texas Record of Criminal Offences” from 1868. Photo: Mayra Beltran / © 2011 Houston Chronicle

The exhibit doesn’t only cover the war years; it goes back into the decades-long tensions over slavery and other sectional issues that led to the war, and devotes considerable space to the postwar period, including the creation of veterans’ groups like the GAR and UCV, reunions, monuments, and so on. It was in the area on the Reconstruction period that I came across a particularly chilling artifact, a big ledger in which the officers of the Freedmens’ Bureau in East Texas recorded assaults and murders of African Americans, attacks believed to be part of the terror campaign led by the Ku Klux Klan and allied groups to limit the new citizens’ participation in the electoral process and to intimidate anyone who challenged the pre-war power structure. The pages on display opened to 1868, the year such depredation came to a climax, in anticipation of that year’s general election. The the neatly-penned columns of names of the victims, alleged perpetrators, and nature of the crime — almost all listed simply as “homicide” — were deeply unsettling.

There is some hands-on material, including a section where visitors are asked to view an illustration from a wartime patent application, and then guess what the object is. The HMNS has also set up a kids’ discovery room, about halfway through, where young visitors can try on period costumes and work puzzles involved Civil War-era cryptography.

The museum has also appended a display at the end of the NARA exhibit, focusing on Texas during the war, with lots of arms and other artifacts from local units. These are, I believe, materials from the John L. Nau III, Civil War Collection. The recent recovery of artifacts from the wreck of the U.S.S. Westfield is discussed, as well.

Finally, there’s an extensive series of public presentations being given on different aspects of the conflict, including one on the recovery of the U.S.S. Westfield artifacts on March 27, and one by myself on March 27, “Patriots for Profit – The Blockade Runners of the Confederacy.” Hope to see y’all there.

_______________

Everyone Knows the Past was Sepia-Toned

Corey has an interesting post up, tracing the history of efforts to locate the exact location of the famous “Harvest of Death” photos, taken shortly after the Battle of Gettysburg. Corey highlights John Cummings’ recent findings (here and a follow-up here), and asks what his readers think. I don’t know, myself — I’ll have to give it more study — but it did get me thinking about colorizing historic, black-and-white photos.

It’s a practice that’s ubiquitous now; there are entire cable teevee series based largely on retroactively colorizing historic footage, presumably to lend some brilliant new insight into the past. Mostly this technique results in a very poor-quality product, and sometimes it’s not even necessary. Here are two images of the destruction of U.S.S. Arizona, on the left a still frame from actual color footage of the blast, and on the right, a still frame from the video linked above, a colorized version of a black-and-white print of the same footage. (I’ve “flopped” the right frame left-to-right; the footage is also usually shown reversed.) In neither case is the footage very clear, but the original color frame is far more natural than the artificial one on the right:

The practice is even more prevalent in print media; historical magazines do it all the time, presumably because they feel it makes the publication more visually appealing.

I was also reminded of the pitfalls of colorizing images by this article about Swedish artist Sanna Dullaway, who’s taken some of the best-known portraits and news images, shot originally in black and white, and colorized them. Her colorized image of Lincoln appears at the top of this post; other subjects include Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, the summary execution of a Viet Cong prisoner during the Tet Offensive, and the famous V-J Day kiss in Times Square.

But her own rendering of the famous “Harvest of Death” image points out one of the obvious limitations of the practice; she gets the uniform colors really, badly wrong. Such errors can be obvious, in cases like this, but in most cases the viewer could have no idea what’s correct. The blue coat, brown vest and scarlet necktie of Lincoln (right), don’t strike me as very plausible — though perhaps they’re more believable than the Great Emancipator’s self-evident spray tan. (Knocking down the color saturation of the image would take care of that distinctly Boehner-like orange glow.)

But her own rendering of the famous “Harvest of Death” image points out one of the obvious limitations of the practice; she gets the uniform colors really, badly wrong. Such errors can be obvious, in cases like this, but in most cases the viewer could have no idea what’s correct. The blue coat, brown vest and scarlet necktie of Lincoln (right), don’t strike me as very plausible — though perhaps they’re more believable than the Great Emancipator’s self-evident spray tan. (Knocking down the color saturation of the image would take care of that distinctly Boehner-like orange glow.)

I’m ambivalent about the practice, myself; I don’t really object to it on grounds of authenticity, if it’s make clear that such an alteration has been made, but it’s rarely done very well. (Sanna Dullaway is much better at it than most Photoshop hacks like me, but even hers are of mixed effectiveness.)

So what do you think? Do colorized images — still or moving — have a place in historical interpretation? What cautions or disclaimers should accompany them? What are the pitfalls, and the benefits? And most important, are there any really good colorizing tutorials out there? 😉

______________

Images: Colorized Lincoln image by Sanna Dullaway. U.S.S. Arizona images by (left) U.S. Naval Historical Center and (right) The Military Channel.

Hearing the Rebel Yell

One of my readers points to this Smithsonian article on motion picture and audio recordings of old Civil War soldiers, shot in the early 20th century. In particular, this is a great video showing a group of old Confederate veterans recreating the famous “rebel yell.” Waite Rawls and the folks at the Museum of the Confederacy made their own effort at recreating the rebel yell, using a couple of recordings like the one above, remastered and remixed into a multitude of voices.

![]()

![]()

_______________

“This congregation of scum and wickedness”

On Friday we had a talk over at Coates’ place about the new series making its debut tonight on AMC, Hell on Wheels. TNC flags a review that cuts to the core of the plot:

The hero is Cullen Bohannon, played by Anson Mount with a grizzled animality and gaunt humanity that help the character to shoulder the burden of history. Bohannon fought for Confederacy. He was a slave owner, but he freed his slaves before the Civil War began, guided by the influence of his wife: “She convinced me of the evils of slavery.” She also did needlepoint, as we see in a dewy-eyed flashback to the days before Union soldiers raped and killed her.

Cliché much? Confederate revenge stories are getting really, really old. Any gravitas they had as a serious plot device surely died along with Quentin Turnbull.

I can imagine the pitch meeting with AMC executives right now — “OK, see, it’s, uh, like Gladiator meets Deadwood. Get it?”

Clearly the producers of this miniseries are trying to bottle the lightning of HBO’s Deadwood. I never followed that series, but (historical license aside) it was highly regarded as a drama, with complex characters and writing that turned traditional Western tropes upside down. It doesn’t sound like Hell on Wheels is even attempting to stake out new territory in the same way. Patterson’s review continues:

The players in this drama are figures in a panoramic diorama. In its world of mud and sepia, feral whores face down lank preachers, Irish immigrant brothers seek their fortunes, Scandinavian-born enforcers looms as creepily as The Seventh Seal‘s Grim Reaper, and noble savages keep on keeping on. Second billing goes to Common, who plays Elam Ferguson, a former slave working for Union Pacific. The actor does a lot of good simmering and dutiful glowering, and his character’s relationship with Bohannon is the richest one on screen. The performance is just good enough to distract you from the fact that Ferguson less resembles an individual than an archetype addressing a few centuries’ worth of racial grievances.

None of Hell on Wheels‘ juicy eruptions of pulp or sporadic glimpses of soul impedes the myth-belching progress of a story about the little engine of empire that could. The shots are heavily styled in a way that is variously enrapturing and distancing, taking cues from landscape paintings, Mathew Brady photographs, and revisionist Westerns—all to the end of toying with the old myths of the New World. But you can hardly see the world for the myths, and the show seems bent on encouraging a sophisticated audience to set its intelligence aside in a sophisticated way.

Doesn’t sound like Hell on Wheels is going to challenge anyone’s thinking about the past in the way that Deadwood did, or The Wire or Breaking Bad even Mad Men do in their more modern settings. That’s a shame because, you know — locomotives! 😉

As a side note, there was a query about the term “Hell on Wheels,” and whether it was an anachronism for the series. It’s certainly not, as it was a contemporary term for the transient settlements of saloon keepers, gambling dens and other distractions of the flesh that followed the rail head snaking west across the plains. The term, in fact, may have been popularized in part by Samuel Bowles’ 1869 book, Our New West, which gave as vivid a description of these places as any ever committed to paper:

As the Railroad marched thus rapidly across the broad Continent of plain and mountain, there was improvised a rough and temporary town at its every public stopping-place. As this was changed every thirty or forty days, these settlements were of the most perishable materials, — canvas tents, plain board shanties, and turf-hovels,—pulled down and sent forward for a new career, or deserted as worthless, at every grand movement of the Railroad company. Only a small proportion of their populations had aught to do with the road, or any legitimate occupation. Most were the hangers-on around the disbursements of such a gigantic work, catching the drippings from the feast in any and every form that it was possible to reach them. Restaurant and saloon keepers, gamblers, desperadoes of every grade, the vilest of men and of women made up this “Hell on Wheels,” as it was most aptly termed.

When we were on the line, this congregation of scum and wickedness was within the Desert section, and was called Benton. One to two thousand men, and a dozen or two women were encamped on the alkali plain in tents and board shanties; not a tree, not a shrub, not a blade of grass was visible; the dust ankle deep as we walked through it, and so fine and volatile that the slightest breeze loaded the air with it, irritating every sense and poisoning half of them; a village of a few variety stores and shops, and many restaurants and grog-shops; by day disgusting, by night dangerous; almost everybody dirty, many filthy, and with the marks of lowest vice; averaging a murder a day; gambling and drinking, hurdy-gurdy dancing and the vilest of sexual commerce, the chief business and pastime of the hours, — this was Benton. Like its predecessors, it fairly festered in corruption, disorder and death, and would have rotted, even in this dry air, had it outlasted a brief sixty-day life. But in a few weeks its tents were struck, its shanties razed, and with their dwellers moved on fifty or a hundred miles farther to repeat their life for another brief day. Where these people came from originally; where they went to when the road was finished, and their occupation was over, were both puzzles too intricate for me. Hell would appear to have been raked to furnish them; and to it they must have naturally returned after graduating here, fitted for its highest seats and most diabolical service.

So if any of y’all watch tonight, I’d be happy to hear your impressions.

Update: Alyssa Rosenberg is equally disappointed in the first few episodes.

______________

Image: Looking west from the 100th Meridian, October 1866. The man in the photo is likely either Samuel B. Reed, chief engineer of construction for the Union Pacific, or Thomas Chase Durant. Library of Congress.

Looking In From the Outside, Black Confederates Edition

Leslie Madsen-Brooks, an assistant professor of history at Boise State University, has put up an essay on the online discussion over BCS. It’s interesting to see an outsider’s view of this business. For those who’ve followed the discussion for a while, it covers a lot of familiar territory, and a lot of familiar names. For folks who are new to the subject, it gives a pretty good lay of the land, and a useful introduction to the characters involved.

Leslie Madsen-Brooks, an assistant professor of history at Boise State University, has put up an essay on the online discussion over BCS. It’s interesting to see an outsider’s view of this business. For those who’ve followed the discussion for a while, it covers a lot of familiar territory, and a lot of familiar names. For folks who are new to the subject, it gives a pretty good lay of the land, and a useful introduction to the characters involved.

And boy howdy, are there some characters. 😉

h/t Kevin Levin and Brooks “Perfesser” Simpson

_______________

Image: Unidentified young soldier in Confederate uniform and Hardee hat with holstered revolver and artillery saber, Library of Congress.

Someone Is Wrong in the Newspaper!

A friend recently pointed me to a guest column in the local paper that I’d missed, challenging the idea of a sesquicentennial celebration of Juneteenth here in 2015. The writer, Robert Hart, peppers his column with “facts” that “Juneteenth proponents should know,” which are mostly wrong. You can read it here. While Hart suggests time would be better spent interviewing African Americans about segregation, which pretty much everyone agrees was a Bad Thing, I suspect he’s mainly interested in deflecting attention off onto something other than the central role of slavery in the Confederacy. His column has almost nothing to do with Juneteenth, offering instead a list of standard Southron Heritage™ talking points about various bad acts perpetrated by the Yankees.

A friend recently pointed me to a guest column in the local paper that I’d missed, challenging the idea of a sesquicentennial celebration of Juneteenth here in 2015. The writer, Robert Hart, peppers his column with “facts” that “Juneteenth proponents should know,” which are mostly wrong. You can read it here. While Hart suggests time would be better spent interviewing African Americans about segregation, which pretty much everyone agrees was a Bad Thing, I suspect he’s mainly interested in deflecting attention off onto something other than the central role of slavery in the Confederacy. His column has almost nothing to do with Juneteenth, offering instead a list of standard Southron Heritage™ talking points about various bad acts perpetrated by the Yankees.

Anyway, the Galveston County Daily News was kind enough to run a guest column of mine today, countering Hart. It’s not great writing on my part, as I found it harder that in oughter be to keep it under 500 words:

Robert Hart recently published a guest column in the GCDN (“Juneteenth proponents should know facts,” Oct. 5), on celebrating the sesquicentennial of Juneteenth in 2015. Mr. Hart’s column, unfortunately, includes a great deal of information that serves only to deflect attention from the subject. Whether or not Ulysses Grant personally owned slaves has nothing to do with the legitimacy of Juneteenth as a day of celebration.

Worse, many of the “facts” Hart includes in his column are demonstrably false. Hart says that Grant “owned slaves in Missouri and freed them only when he had to.” In fact, Grant is known to have owned a single slave during his lifetime, a man named William Jones, possibly received from his father-in-law, probably in 1858. Grant formally manumitted (freed) Jones in March 1859.[1]

Hart claims that Robert E. Lee “freed his slaves 10 years before the war.” Not true. As biographer Elizabeth Brown Pryor discovered in going through the general’s papers, Lee personally owned slaves at least as late as 1852, considered buying more shortly before the war began, and used slaves as personal servants throughout the war itself. More important, from late 1857 onward he was acting as executor of his father-in-law’s estate at Arlington House, where he ruled with a far stricter hand than the Custises ever had. There’s credible evidence that he personally supervised the whipping of runaway Arlington slaves in 1859.[2] Lee did not formally manumit these slaves until the end of 1862.[3]

Hart continues, saying that “the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t free a single slave when it was issued.” Again, not true. As Eric Foner points out in his recent, Pulitzer Prize-winning book on Lincoln and emancipation, the order freed tens of thousands of slaves immediately in Union-occupied areas, and firmly established permanent emancipation as official war policy.[4] The Emancipation Proclamation made the Union Army a rolling, blue tide of emancipation. More than any battlefield victory, the Emancipation Proclamation doomed the Confederacy.

Hart argues that slavery in the United States ended with the passage of the 13thAmendment, but meaningful emancipation occurred over decades, and slaves themselves often made it happen. Some “stole themselves” from their masters. Tens of thousands of former slaves took up arms to free their kindred as part of the Union Army’s famed U.S. Colored Troops. Many more were emancipated (like those in Texas) when the Federal army arrived to enforce the Emancipation Proclamation.

Emancipation and the end of slavery are worth celebrating – not just for African Americans, but for all Americans who value liberty and freedom. Every date on the calendar is the anniversary of some small piece of that story, but some dates carry more significance than others. For both practical and symbolic reasons, June 19 is the best choice for Galveston, for Texas, and for the nation.

[1] Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822‐1865 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2000), 71-72.

[2] Elizabeth Brown Pryor, Reading the Man: A Portrait of Robert E. Lee Through His Private Letters (London: Penguin, 2007), 270-73.

[3] Emory M. Thomas, Robert E. Lee: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1995), 273.

[4] Eric Foner, The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2010), 243.

Of course, h/t to Bob Pollock, who continues to do the bloggy knowledge on Grant.

___________

“Facial hair and longish hair are a big plus.”

Casting is open in Richmond for extras in Spielberg’s adaptation of Doris Kearns Goodwin’s Team of Rivals.

Filming for the project – with a working title of “Office Seekers” – is expected to begin within the next couple of weeks and last until December, but the exact dates and locations remain a secret. “With the casting wrapping up, you can tell that they will start filming soon,” said Mary Nelson, communications director with the Virginia Film Office. . . .

Just days before the beginning of filming, the casting crew is still looking for Caucasian and African-American men. All must be 18 years of age or older, between 6’1″ or under, 200 pounds or less. Facial hair and longish hair are a big plus. Men with shaved heads, dreads, braids or piercings need not apply.

“We are especially looking for men to portray African-American Union soldiers,” Dowd said. Other extra roles for African-Americans include slaves. “We’re still looking for servants for White House scenes, so restaurant experience is a plus,” Dowd said.

Other openings still available include African-American women. Long hair is not necessary, but no dreads, braids, modern cuts or wigs. Dress size should be between 6 and 12. The casting crew is also looking for Caucasian women with longish hair of natural color, dress size between 6 and 12.

Dowd said that the job pays $79.75 per day for up to 10 hours or less. But extras are sometimes required to stay on set for up to 12 hours or longer. “We’ll need many extras for more than one day, which makes this a great opportunity for people who are currently without a job,” Dowd said.

Applicants may send a recent photo to osextrascasting@gmail.com along with height, weight and contact information or mail to Office Seekers, Attn: Extras Casting, 8080 AMF Drive, Mechanicsville, VA 23111.

The high-profile project has not gone unnoticed by heritage groups, which have a tendency to react to anything that depicts the Lincoln administration in a sympathetic or positive light. A few days ago there was a reception for Spielberg at the Governor’s Mansion in Richmond (above), which was duly protested by the “Virginia Flaggers,” who work to promote the display of the Confederate flag and, in this case, to remind the director “of the truth about Lincoln and the ultimate sacrifice made by over 32,000 Virginians in defense of the Commonwealth.”

Governor McDonnell, of course, has been declared an enemy by these same folks for the last eighteen months, since he retracted his original 2010 Confederate History Month proclamation, one reportedly written by the Virginia SCV. McDonnell subsequently announced that Confederate History Month would be replaced by a more inclusive Civil War in Virgina Month. In response, senior SCV officials went so far as to hold a press conference “to outline the ‘ongoing failures’ ” of the governor “to deal with a variety of history and heritage issues in Virginia.” They threw in a denouncement of former Governor George Allen (of “macaca” infamy) who had publicly distanced himself from the organization while in office.

Should we expect even more carping in the wake of Tuesday’s announcement that the Virginia State Capitol, which served as the Confederate Capitol during the war, will be used as a filming location? You can bet on it. Today, in 2011, Virginia is shaping up to be central battleground of memory of the conflict of 1861-65.

_________

Image: Gov. Bob McDonnell welcomed filmmaker Steven Spielberg to the governor’s mansion for a reception on Monday. Via Roanoke.com. Thanks to Jimmy D at Coates’ place for suggesting this story.

Mustering Black Confederates

A new page added to the blog, indexing by category my previous postings on black Confederate soldiers.

____________

Image: Ransom Gwynn (seated) with white Confederate veterans at what was billed as the “Last Confederate Reunion” at Montgomery, Alabama in September 1944. Rev. Gwynn attended at least two Confederate reunions (1937 and 1944) on the claim that he had been a “body guard” to his former master, but historical records indicate Gwynn was likely not more than 11 years old, and perhaps as young as 8 or 9, when the war ended. Alabama Department of Archives and History.

Too Many Historians, Too Little Time

Blog reader dmf alerted me this morning to today’s Diane Rehm Show on NPR, that devoted an hour to the subject of The Civil War: America’s 2nd Revolution, with particular emphasis on the coming of the war and the way it’s perceived today. I don’t usually have a chance to listen to Rehm’s show, but the panel today was A-List: Adam Goodheart, author of 1861: The Civil War Awakening; David Blight, author of Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, the upcoming American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era, and a popular undergrad lecture series available online; Thavolia Glymph, author of Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household; and Chandra Manning, author of What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War.

Blog reader dmf alerted me this morning to today’s Diane Rehm Show on NPR, that devoted an hour to the subject of The Civil War: America’s 2nd Revolution, with particular emphasis on the coming of the war and the way it’s perceived today. I don’t usually have a chance to listen to Rehm’s show, but the panel today was A-List: Adam Goodheart, author of 1861: The Civil War Awakening; David Blight, author of Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, the upcoming American Oracle: The Civil War in the Civil Rights Era, and a popular undergrad lecture series available online; Thavolia Glymph, author of Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household; and Chandra Manning, author of What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War.

They covered a lot of ground, and easily could have gone on for another hour. I’ll have more to say when the episode’s transcript is posted, but for now you can listen online.

Update: Transcript here.

____________

8 comments