“The whole country, North and South, should thank Him for this step.”

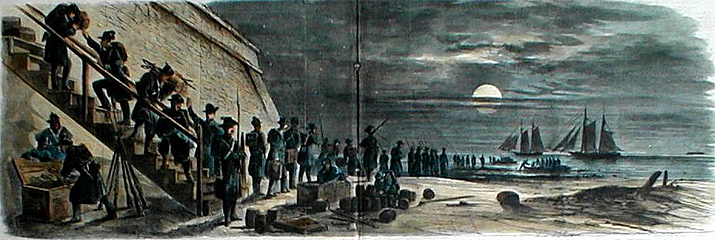

A hundred fifty years (and a few days) ago, Major Robert Anderson quietly evacuated his command at Fort Moultrie, South Carolina, to Fort Sumter, an unfinished installation in Charleston Harbor. In doing so, he ceded the indefensible Moultrie to the South Carolina secessionists, and set the stage for the “Sumter crisis” that would play out over the next several weeks.

In the wake of South Carolina’s secession on December 20, Anderson’s orders from the Secretary of War, dated December 21, were somewhat contradictory. In the two-page memo, he is first enjoined, if attacked, to “defend yourself to the last extremity.” Then, he is reminded that “it is neither expected nor desired that you should expose your own life or that of your men in a hopeless conflict in defense of the Forts. If they are invested or attacked by a force so superior that resistance would in you judgment be a useless waste of life it would be your duty to yield to necessity and make the best terms in your power.”

Even as the War Department sent those orders, a delegation from South Carolina was en route to Washington to demand the surrender of Moultrie and the other U.S. military installations around Charleston Harbor. Both sides expected the Buchanan administration to refuse, and both sides then expected Moultrie to be overrun by South Carolina militia called up in response to that state’s withdrawal from the Union. The outcome seemed pre-ordained.

What Anderson did on December 26, on his own initiative, was change the game from the way both Washington and the secessionists expected it eventually to play out. Between six and eight p.m., Anderson spiked Moultrie’s guns, burned their carriages, cut down the flagpole and transferred his entire command to Sumter. The next day, in response to an incredulous telegram from a War Department caught blindsided by his action, Anderson wired back:

The telegram is correct. I abandoned Fort Moultrie because I was certain that, if attacked, my men must have been sacrificed and the command of the harbor lost. I spiked the guns and destroyed the carriages to keep the guns from being used against us. If attacked, the garrison would never have surrendered without a fight.

Anderson speaks here explicitly to his commitment to both the men of his command and to his mission as a soldier — had he waited for the expected assault on Moultrie, “my men must have been sacrificed and the command of the harbor lost.” In a letter to his wife, dated at the time for their arrival at Sumter, Anderson (like many of his contemporaries) credits God with guiding the wisdom of his action:

Fort Sumter, S. C.,

8 P. M., Dec. 26, 1860.Thanks be to God. I give them with my whole heart for His having given me the will, and shewn me the way to bring my command to this Fort. I can now breathe freely. The whole force of S. Carolina would not venture to attack us. Our crossing was accomplished between six and eight o’clock. I am satisfied that there was no suspicion of what we were going to do. I have no doubt that the news of what I have done will be telegraphed to New York this night. We saw signal rockets thrown up all around just as our last boat came over. I have not time to write more—as I must make my report to the Ad. Genl. . . . Praise be to God for His merciful kindness to us. I think that the whole country North and South should thank Him for this step.

I like that last line, “I think that the whole country North and South should thank Him for this step.” I doubt either side did at the time, but I think Anderson was right — he thought (to use a bad, modern cliche) “outside the box” and pushed back the direct, armed conflict for more than three months.

In its ongoing Civil War series, “A House Divided,” the Washington Post asks several prominent historians whether evacuating Moultrie was Anderson’s best option. So far Joan Waugh, Frank J. Williams, and Scott Hartwig all agree: Major Anderson had no alternative, short of outright capitulation. Hartwig:

Anderson had 74 officers and men in two artillery companies at Ft. Moultrie, but after deducting the noncombatants – musicians, sick and those under arrest for various reasons – his effective strength was about half that. Moultrie’s purpose was for its guns to cover the channel leading from the open sea into Charleston harbor, not defend against an attack from the rear. The fort’s defenses were so vulnerable to land attack that no competent army officer would have considered attempting to defend it. Wind had blown sand up so high against the fort’s walls that cattle could climb up, walk through the embrasures and onto the parapet. Sand dunes east of the fort rose higher than the fort’s walls and provided excellent firing positions for an attacker. All of the buildings in the fort except for the fortifications were wood and easily burned. There were private houses on the east side of the fort and cottages on the west side, which could provide additional cover for an attacker. But a competent attacker did not need to assault the fort. Sitting on a peninsula of Sullivan’s Island it could easily be cut off and the garrison starved into surrender.

Following the December 20 secession of South Carolina, Anderson learned that preparations were underway to attack Moultrie if the negotiations between South Carolina’s commissioners and the Buchanan administration failed to secure its surrender. Anderson already knew that Buchanan probably would not surrender the fort so it was necessary to act quickly. Fort Sumter was the only defensible point available to Anderson and his small garrison. It could not be attacked by land and could be reinforced and resupplied by water. On the evening of December 26, in a cleverly planned and executed operation, the garrison made the transfer from Moultrie to Sumter without incident.

Though it infuriated the secessionists at the time, who thought they’d been played (they had), it seems clear now that Anderson’s move was the correct one, both politically and militarily. It held off direct, armed conflict, maintained a symbolic U.S. military presence at Charleston, and bought both sides more than three months’ time to reach a peaceful resolution to the dispute. In modern parlance, Anderson “dialed it back” by evacuating Moultrie and removing his men to Sumter. More to the point, it’s hard to see why Anderson would do anything else; although a pro-slavery Kentuckian and a former slaveholder himself, he saw his first allegiance to his assignment, and to his immediate command. Anderson couldn’t control events outside Moultrie’s walls, but he recognized that both Washington and the secessionists had effectively locked themselves into courses of action that would have destroyed his command and yielded any U.S. control over the harbor. In the absence of clear directives from Washington, he responded to them as a professional soldier should, with careful deliberation and planning, followed by decisive execution, in a way that gave the government — both governments — time and options to avert the looming crisis.

Though it infuriated the secessionists at the time, who thought they’d been played (they had), it seems clear now that Anderson’s move was the correct one, both politically and militarily. It held off direct, armed conflict, maintained a symbolic U.S. military presence at Charleston, and bought both sides more than three months’ time to reach a peaceful resolution to the dispute. In modern parlance, Anderson “dialed it back” by evacuating Moultrie and removing his men to Sumter. More to the point, it’s hard to see why Anderson would do anything else; although a pro-slavery Kentuckian and a former slaveholder himself, he saw his first allegiance to his assignment, and to his immediate command. Anderson couldn’t control events outside Moultrie’s walls, but he recognized that both Washington and the secessionists had effectively locked themselves into courses of action that would have destroyed his command and yielded any U.S. control over the harbor. In the absence of clear directives from Washington, he responded to them as a professional soldier should, with careful deliberation and planning, followed by decisive execution, in a way that gave the government — both governments — time and options to avert the looming crisis.

Robert E. Lee famously cast his lot with Virginia and the Confederacy, but that only came months later, when he felt his own, home state was threatened. Had Lee been in command at Moultrie in December 1860, I suspect he would have done exactly the same thing.

____________________

Ed. Note: The post has been extensively rewritten in response to a reader’s inquiry in the comments, below. Thanks to him for providing the impetus for this. Image: Evacuation of Fort Moultrie by W. R. Waud, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper.

“You can expect no help from this side of the river.”

The Museum of the Confederacy recently announced the discovery of a coded message enclosed in a tiny bottle that’s been sitting, unopened, in the museum’s collection for over a century. The decoded text of the message reads:

Gen’l Pemberton: You can expect no help from this side of the river. Let Gen’l Johnston know, if possible, when you can attack the same point on the enemy’s lines. Inform me also and I will endeavor to make a diversion. I have sent some caps [i.e., percussion caps]. I subjoin a despatch from General Johnston.

The message is dated July 4, 1863, the same day that Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to General Grant. Pemberton never got the message, and it would not have mattered if he had.

The message is unsigned, but the author, who clearly was unaware of Pemberton’s true situation in Vicksburg, may have been Major General John George Walker (l.), at that time commanding a division in the Confederacy’s Trans-Mississippi Department, and operating in western Louisiana. The message was encoded using the “Vigenère cipher,” in which the letters of the original message are shifted so many spaces over, so that A becomes M, B becomes N, and so forth, based on a key word or phrase known to both the sender and the recipient. Although ciphers of this type had a reputation of being unbreakable, most of the Confederate messages sent in this way that were intercepted by the Federals were quickly decoded. The fact that most Confederate messages used one of only three key phrases, “Manchester Bluff,” “Complete Victory,” and “Come Retribution,” made them more vulnerable than they should have been. (After tinkering with this Vigenère cipher generator, it seems this message used “Manchester Bluff” as its key, at least for the first few words.) As so often with cryptanalysis throughout history, the key to breaking a code often comes from mistakes on the part of the sender.

The message is unsigned, but the author, who clearly was unaware of Pemberton’s true situation in Vicksburg, may have been Major General John George Walker (l.), at that time commanding a division in the Confederacy’s Trans-Mississippi Department, and operating in western Louisiana. The message was encoded using the “Vigenère cipher,” in which the letters of the original message are shifted so many spaces over, so that A becomes M, B becomes N, and so forth, based on a key word or phrase known to both the sender and the recipient. Although ciphers of this type had a reputation of being unbreakable, most of the Confederate messages sent in this way that were intercepted by the Federals were quickly decoded. The fact that most Confederate messages used one of only three key phrases, “Manchester Bluff,” “Complete Victory,” and “Come Retribution,” made them more vulnerable than they should have been. (After tinkering with this Vigenère cipher generator, it seems this message used “Manchester Bluff” as its key, at least for the first few words.) As so often with cryptanalysis throughout history, the key to breaking a code often comes from mistakes on the part of the sender.

The message was decoded and its contented confirmed by a retired CIA cryptanalist, David Gaddy, and an active-duty U.S. Navy intelligence officer, Cmdr. John B. Hunter.

______________________

Image: This Jan. 14, 2009 image shows a Civil War bottle with a message that was tucked inside at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Va. The message to Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton says reinforcements will not be arriving. The encrypted dispatch was dated July 4, 1863 — the date of Pemberton’s surrender to Union forces led by Ulysses S. Grant in what historians say was a turning point in the war. (AP Photo/Museum of the Confederacy)

John B. Gordon, “Faithful Servants,” and Veterans’ Reunions

Recently I came across a passage in General John B. Gordon’s Reminiscences of the Civil War (1903, pp. 382-84) that, while discussing the eleventh-hour decision of the Confederate government to enlist slaves as soldiers in the final weeks of the conflict, reveals a great deal about the nature of slaves’ other service in the Confederate army, and how they themselves sometimes presented themselves both during the war and decades later.

John Brown Gordon (1832-1904) was an attorney with no military experience when the war began, but he was elected captain of a company he raised, and by late 1862 had been promoted to the rank of brigadier general. He quickly became famous for his bravery under fire, and was wounded numerous times. He served throughout the war with the Army of Northern Virginia, eventually rising to the rank of major general (he claimed lieutenant general), and commanding the Second Corps of that army. Gordon saw action at most of the Army of Northern Virginia’s major engagements, including First Manassas, Malvern Hill, Sharpsburg, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and the Siege of Petersburg. Gordon surrendered his command to another famous civilian-turned-general, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, in April 1865. After the war, he fought against Reconstruction policies — allegedly as a leader of the Klan — and later served as a U.S. senator and as governor of Georgia. In 1890 he was elected first Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans, a post he held until his death.

John Brown Gordon (1832-1904) was an attorney with no military experience when the war began, but he was elected captain of a company he raised, and by late 1862 had been promoted to the rank of brigadier general. He quickly became famous for his bravery under fire, and was wounded numerous times. He served throughout the war with the Army of Northern Virginia, eventually rising to the rank of major general (he claimed lieutenant general), and commanding the Second Corps of that army. Gordon saw action at most of the Army of Northern Virginia’s major engagements, including First Manassas, Malvern Hill, Sharpsburg, Gettysburg, the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and the Siege of Petersburg. Gordon surrendered his command to another famous civilian-turned-general, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, in April 1865. After the war, he fought against Reconstruction policies — allegedly as a leader of the Klan — and later served as a U.S. senator and as governor of Georgia. In 1890 he was elected first Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans, a post he held until his death.

In his memoir, Gordon describes the debate surrounding the proposed enlistment of slaves in the Confederate army in the closing weeks of the war:

Again, it was argued in favor of the proposition that the loyalty and proven devotion of the Southern negroes [sic.] to their owners would make them serviceable and reliable as fighters, while their inherited habits of obedience would make it easy to drill and discipline them. The fidelity of the race during the past years of the war, their refusal to strike for their freedom in any organized movement that would involve the peace and safety of the communities where they largely outnumbered the whites, and the innumerable instances of individual devotion to masters and their families, which have never been equaled in any servile race, were all considered as arguments for the enlistment of slaves as Confederate soldiers. Indeed, many of them who were with the army as body-servants repeatedly risked their lives in following their young masters and bringing them off the battlefield when wounded or dead. These faithful servants at that time boasted of being Confederates, and many of them meet now with the veterans in their reunions, and, pointing to their Confederate badges, relate with great satisfaction and pride their experiences and services during the war. One of them, who attends nearly all the reunions, can, after a lapse of nearly forty years, repeat from memory the roll call of the company to which his master belonged.

My emphasis. Like another dyed-in-the-wool, senior and well-connected Confederate general, Howell Cobb, Gordon discusses the proposal to enroll slaves as soldiers without making any mention of the supposedly-widespread practice of African Americans serving in exactly that capacity.

Far more important, though, is what he does say. Gordon’s description of enslaved body servants, and their ongoing attachment to the Confederacy, is essential. He notes that they “boasted of being Confederates, and many of them meet now with the veterans in their reunions, and, pointing to their Confederate badges, relate with great satisfaction and pride their experiences and services during the war.” This is a critical observation, and explains much of what is now taken as “evidence” of African American men serving as soldiers during the war. Advocates for the notion that large numbers of black men served as soldiers in the Confederate army routinely point to images of elderly African American men at veterans’ reunions and argue that those men wouldn’t have been present had they not been seen as co-equal soldiers themselves. As we’ve seen, the historical record, when available, can disprove that assumption. And now we have General John B. Gordon, Commander-in-Chief of the United Confederate Veterans, writing exactly the same thing about what he saw around him, as the popularity of veterans’ reunions reached its peak. Gordon clearly takes pride in the former slaves’ commitment to the memory of the Confederacy — again, “faithful servants” — but he never credits any greater wartime service to them. Indeed, Gordon continues with an anecdote mocking the idea of such men being considered soldiers:

General Lee used to tell with decided relish of the old negro (a cook of one of his officers) who called to see him at his headquarters. He was shown into the general’s presence, and, pulling off his hat, he said, “General Lee, I been wanting to see you a long time. I ‘m a soldier.”

“Ah? To what army do you belong—to the Union army or to the Southern army ?”

“Oh, general, I belong to your army.”

“Well, have you been shot ?”

“No, sir; I ain’t been shot yet.”

“How is that? Nearly all of our men get shot.”

“Why, general, I ain’t been shot ’cause I stays back whar de generals stay.”

This anecdote reinforces Gordon’s (and Lee’s) dismissal of the idea that the service of black men like the cook should be considered soldiers; what made the story amusing to both generals is that the man’s claim to status as a soldier was, to their thinking, preposterous on its face. To be sure, Gordon shows real affection for these old African American men who, in his view, remain loyal to the cause. Nonetheless, he can’t help but make gentle mockery of their pretensions to be soldiers. He never considered them to be soldiers in their own right, which is the point of heaping praise on them as “faithful servants.” Lee understood that, Gordon understood that, and Gordon counted on his readers in 1903 to understand that.

So why is that so hard to understand now?

West Point, Annapolis Records Now Online

In honor of Veterans Day, Ancestry.com has put online Military Academy and Naval Academy cadet records and applications from 1805 to 1908. These files will be available free through Sunday, November 14, after which they will be available by subscription. Not sure if there will be an additional fee, or if access to these new materials will be included in existing Ancestry subscriptions.

Entirely apart from being a tool for one’s own genealogy, I’ve found Ancestry to be a great resource for researching individual people more generally, what with its easy access to census records, birth and death notices, slave schedules, and so on. These additional West Point and Annapolis materials are a wonderful addition to Ancestry’s expanding scope. Can’t wait to dig in properly.

Are Pardoned Confederates Still Confederates?

If a Confederate officer takes an oath of allegiance to the United States and the Union, has he forfeited his status as a Confederate?

That’s not a snarky comment or a rhetorical question — I’m entirely serious in asking it.

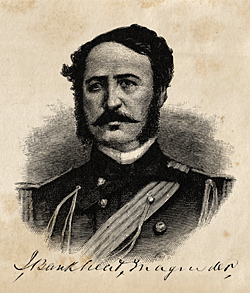

Not far from my home is the grave of Major General John Bankhead Magruder, a well-known Confederate officer and a local hero who commanded the Department of Texas during the middle of the war and organized the naval and land attack that retook Galveston from Union forces on New Years Day, 1863. After the war, and a brief stint in the service of Maximilian’s army in Mexico, Magruder settled in Houston, where he died in 1871. He was initially buried in there, but his remains were subsequently re-interred in Galveston’s Episcopal Cemetery.

Not far from my home is the grave of Major General John Bankhead Magruder, a well-known Confederate officer and a local hero who commanded the Department of Texas during the middle of the war and organized the naval and land attack that retook Galveston from Union forces on New Years Day, 1863. After the war, and a brief stint in the service of Maximilian’s army in Mexico, Magruder settled in Houston, where he died in 1871. He was initially buried in there, but his remains were subsequently re-interred in Galveston’s Episcopal Cemetery.

At the end of May 1865, President Andrew Johnson issued a general amnesty for those who had served the Confederacy; under this amnesty, all rights and property (except for slaves) were to be restored upon taking the oath to support and defend the Constitution of the United States. Fourteen categories of persons were explicitly excluded from this blanket amnesty, including army officers above the rank of colonel. These excluded persons were required to submit a formal application for pardon, “and so realize the enormity of their crime.” While there was never any real doubt that the vast majority of former Confederates would eventually be eligible for pardon, Johnson was determined to use the pardon process to make manifest a point he mentioned often: “treason is a crime and must be made odious.” Over the next three years, the Johnson administration issued about 13,500 individual pardons.

Magruder applied for his pardon in November 1867, and included a letter of from Union Major General Carl Schurz, attesting to his loyalty. Magruder’s application was approved by Attorney General Henry Stanbery on December 9.

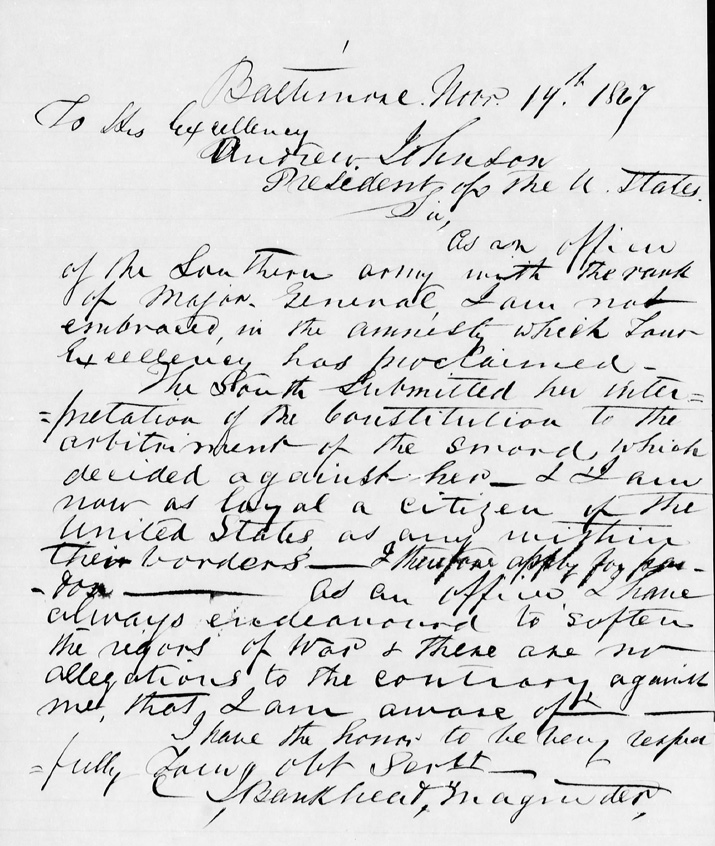

National archives, Case Files of Applications from Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons (“Amnesty Papers”), 1865-67, via Footnote.com

Baltimore, Novr. 14th, 1867

To His Excellency

Andrew Johnson

President of the United StatesSir, as an officer of the Southern army with the rank of Major General, I am not embraced in the amnesty which Your Excellency has proclaimed.

The South submitted her interpretation of the Constitution to the arbitrament of the sword which decided against her — an I am now as loyal a citizen of the United States as any within their borders — I therefore apply for a pardon — As an officer, I have always endeavored to softne the rigors of War & there are no allegations to the contrary, against me, that I am aware of.

I have the honor to be very respectfully Your Obt Servt,

J. Bankhead Magruder

A pardon is not a small thing. A petition for pardon acknowledges and admits a serious legal or moral transgression on the part of the applicant; issuance of a pardon is a formal act of forgiveness, with the implicit understanding that the offense being pardoned is real, is ended and will not be repeated.

There’s no way to parse or explain away Magruder’s declaratory statement, written in his own hand, that “I am now as loyal a citizen of the United States as any within their borders.” Major General Walker signed an even more explicit statement, that he would “henceforth faithfully support, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States and the Union of the States thereunder,” closing with, “so help me God.”

Are these pledges of loyalty to be taken seriously? It would seem they must be; after all, the core values of loyalty, devotion and personal honor are some of the very things that motivate the desire to recognize these men in the first place. But they voluntarily, formally and explicitly rejected any allegiance to the Confederacy; it’s hard to see how they can still be legitimately considered Confederates. Certainly most Americans today would hesitate to honor an American soldier who formally renounced his American citizenship in favor of another nation’s.

Or should we assume that applying for a pardon and swearing ongoing allegiance to the United States — “in the presence of ALMIGHTY GOD” — was something they simply had to do to get along, and they never really meant it? That it was just what they had to do to get on with their lives? Path of least resistance? Doubtful.

So we’re back to the first option: that these men willingly, voluntarily rejected any further allegiance to the Confederacy. How, then, can they now logically be honored for their loyalty to that defunct nation? There’s not an easy answer to this question; I don’t even think there is an answer that makes any objective sense. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t ask the question.

Ambrose Bierce “On Black Soldiering”

A skeptical correspondent asks me for an opinion of the fighting qualities of our colored regiments. Really I had thought the question settled long ago. The Negro will fight and fight well. From the time when we began to use him in civil war, through all his service against Indians on the frontier, to this day he has not failed to acquit himself acceptably to his White officers. I the more cheerfully testify to this because I was at one time a doubter. Under a general order from the headquarters of the Army, or possibly from the War Department, I once in a burst of ambition applied for rank as a field officer of colored troops, being then a line officer of white troops. Before my application was acted on I had repented and persuaded myself that the darkies would not fight; so when ordered to report to the proper board of officers, with a view to gratification of my wish, I “backed out” and secured “influence” which enabled me to remain in my humbler station.

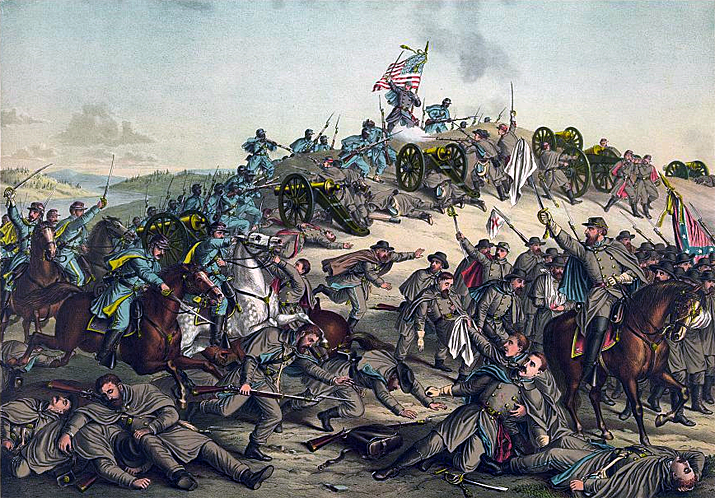

But at the battle of Nashville it was borne in upon me that I had made a fool of myself. During the two days of that memorable engagement the only reverse sustained by our arms was in an assault upon Overton Hill, a fortified salient of the Confederate line on the second day. The troops repulsed were a brigade of Beatty’s division and a colored brigade of raw troops which had been brought up from a camp of instruction at Chattanooga. I was serving on Gen. Beatty’s staff, but was not doing duty that day, being disabled by a wound — just sitting in the saddle and looking on. Seeing the darkies going in on our left I was naturally interested and observed them closely. Better fighting was never done. The front of the enemy’s earthworks was protected by an intricate abatis of felled trees denuded of their foliage and twigs. Through this obstacle a cat would have made slow progress; its passage by troops under fire was hopeless from the first — even the inexperienced black chaps must have known that. They did not hesitate a moment: their long lines swept into that fatal obstruction in perfect order and remained there as long as those of the white veterans on their right. And as many of them in proportion remained until borne away and buried after the action. It was as pretty an example of courage and discipline as one could wish to see. In order that my discomfiture and humiliation might lack nothing of completeness I was told afterward that one of their field officers succeeded in forcing his horse through a break in the abatis and was shot to rags on the slope on the parapet. But for my abjuration of faith in the Negroes’ fighting qualities I might perhaps have been so fortunate as to be that man!

San Fransisco Examiner, June 5, 1898. From Russell Duncan and David Klooster, Phantoms of a Blood-Stained Period: The Complete Civil War Writings of Ambrose Bierce. Image: “Battle of Nashville,” Kutz & Allison Lithograph, Library of Congress.

Prayer in Battle

If a man is good he thinks all men are more or less worthy; if bad he makes all mankind co-defendants. That comes of looking into his own heart and fancying that he surveys the world. Naturally the Rev. W. S. Hubbell, Chaplain in the Loyal Legion, is a praying man, as befits him. When in trouble he asks God to help him out. So he assumes that all others do the same. At a recent meeting of a Congregational Club to do honor to General Howard on that gentleman’s seventieth birthday (may he have a seventy-first) Dr. Hubbell said: “I bear personal testimony that if ever a man prays in his life it is in the midst of battle.”

My personal testimony is the other way. I have been in a good many battles, and in my youth I used some times to pray — when in trouble. But I never prayed in battle. I was always too much preoccupied to think about it. Probably Dr. Hubbell was misled by hearing in the battle the sacred Name spoken on all sides with great frequency and fervency. And probably he was too busy with his own devotions to observe, or, observing, did not understand the mystic word that commonly followed — which, as nearly as I can recollect, was “Dammit.”

Ambrose Bierce, San Fransisco Examiner, December 2, 1900

_____________________

The Loyal Legion was a group of Federal military officers pledged to defend the Union against an ongoing, Confederate insurgency in the immediate aftermath of President Lincoln’s assassination. It included many of the most famous officers in the Union military, including Grant, Sherman, and Farragut. No widespread insurrection developed, of course, and over time the Legion evolved into a fraternal and heritage organization.

The Greatest American Soldier Since George C. Scott

Rich Iott’s campaign website makes much of his military experience:

Rich is a proud member of the Ohio Military Reserve, a component of the Adjutant General’s Department of the State of Ohio, where he holds the rank of Colonel. He is in his 28th year of service. He is a graduate of the USMC Command and Staff College and the USAF Air War College. He has been awarded the highly coveted Israeli jump wings and the Senior Parachutist wings of The Netherlands.

You gotta love the bit about “Israeli jump wings.” How many Waffen SS reenactors can claim that, I wonder.

In response, the Toledo Blade does due diligence and discovers that there’s less there than meets the eye:

One glossy mailing portrays Mr. Iott in civilian and military garb and says, “Rich Iott understands the sacrifices our men and women in uniform have made because he serves himself.”

Another one says, “Reservist Rich Iott will stand up and fight for our veterans.”

But Mr. Iott’s claim to be a member of the military, when he was never on active duty, have rankled those serving in or retired from the armed forces.

Retired Ohio Adjutant General John Smith, a Vietnam veteran who was once commander of the 180th Air National Guard fighter wing based at Toledo, said the OMR has no role in the national defense and has never been called up for duty.

“He’s stretching it in terms of what the Ohio Military Reserve does. He’s giving the impression, I would suggest, that he is involved in matters related to national security and to state matters, and they are not. They are never consulted,” General Smith said.

General Smith said it’s unlikely the governor ever will activate the reserve because of the cost of paying a lot of high-ranking reservists.

The Ohio Military Reserve is a state organization, operating under the Ohio Adjutant General. It is an unarmed, volunteer organization that cannot be called up for national service, like the National Guard or Army Reserve. The State of Ohio can call out the Ohio Military Reserve in the event of an emergency, but never has in the organization’s entire history. Its annual budget is $15,000.

But man, look at those ribbons. Commenter Will, in response to my previous post, nailed it: “Okay, so I got this one for helping out at the first aid tent at the 1997 Cleveland Marathon, and this one was when we beat Indiana at paintball in 2001. . . .”

Twenty years ago, I volunteered for a few months with the local Coast Guard Auxiliary flotilla. They were nice folks and it was a good deal — taught me a lot about boating safety, got me out on the water, performed a useful public service, and so on. It seems roughly comparable to Iott’s involvement with the Ohio Military Reserve. But damn me if I’d ever claim military veteran status over that. What a dishonest poseur.

_________________________

Image: Toledo Blade.

The Nazi Fanboys

There are exactly four blogs on the intertubes that haven’t addressed the recent revelation that a candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives in Ohio is a military reenactor. Specifically, a World War II German reenactor. More specifically still, an S-freaking-S reenactor, from a unit that has been implicated in serious war crimes. Make that three blogs, because I’m now putting down some of my own thoughts on the matter.

Not long ago, Josh Green of The Atlantic broke a story that Rich Iott (left), the GOP nominee for Ohio’s 9th Congressional District (Toledo), was for three years (2004-07) a reenactor with Wiking Division, a group of World War II reenactors based in the Upper Midwest. Iott is a long-time reenactor, but the fact that he spent a few years play-acting a Nazi is, understandably, a political bombshell. Though he was always a long-shot in the general election — he’s running against a long-time Democratic incumbent, Marcy Kaptur, in a deep-blue district — the Wiking revelation effectively puts paid to this and any future campaign Mr. Iott may be considering.

Not long ago, Josh Green of The Atlantic broke a story that Rich Iott (left), the GOP nominee for Ohio’s 9th Congressional District (Toledo), was for three years (2004-07) a reenactor with Wiking Division, a group of World War II reenactors based in the Upper Midwest. Iott is a long-time reenactor, but the fact that he spent a few years play-acting a Nazi is, understandably, a political bombshell. Though he was always a long-shot in the general election — he’s running against a long-time Democratic incumbent, Marcy Kaptur, in a deep-blue district — the Wiking revelation effectively puts paid to this and any future campaign Mr. Iott may be considering.

In the political scheißesturm that followed, the Wiking group rallied some support from other reenactor groups, including this statement from the Mid-Michigan Chapter of the 82nd Airborne Division Association, which accuses Iott’s critics as playing a “twisted political game” and perpetrating a “blatant lie:”

Reenactors reflect every nation involved in WWII. We have seen not only American and German reenactors, but British, Dutch, French, Polish, Russian, Japanese, Italian and a host of others. To use an educational hobby which provides a teaching tool for all Americans in some twisted political game is not only omitting the true facts, but a blatant lie by conversion of the truth.

They doth protest too much. One of my uncles was a member of the 101st Airborne Division during World War II. I don’t know many details of his service; he died when I was little and he didn’t talk to other family members about those parts of the war. But I know that he witnessed the liberation of some of the concentration camps they discovered at the end of the war. (It may have been a situation like that depicted in Band of Brothers; I don’t really know.) I have no idea how he would’ve viewed modern hobbyists recreating American airborne troops, but it’s impossible for me to believe that he would’ve had any use at all for Rich Iott and his Wiking reenactor buddies.

Rich Iott is not a Nazi. But the objective evidence is that, as a practical matter, he is an imbecile, ein schwachkopf, and that he and his Wiking kameraden are willfully ignoring the very ugly history of the unit they model themselves after. It’s a degree of intentional compartmentalization that’s just staggering. They aren’t Holocaust deniers, who are (for better or worse) straight up about their beliefs; they’re something more insidious, folks for whom it just doesn’t much register. Of all the World War II German military formations, these guys have chosen to recreate the SS, and specifically a unit, the Wiking Division, that was recruited in the occupied countries in the West — Norway, Belgium, the Netherlands — to be composed of men of similar Aryan characteristics to the German SS, or “related stock,” as Himmler put it. The division was explicitly recruited to serve in the East; the antisemitic underpinnings of the SS are explicit in the division’s recruiting materials. Recruiting posters, printed in the local language, sought volunteers to join the fight against Bolshevism, which — inevitably — the Nazis intentionally conflated with Judaism. It’s very ugly stuff, and the Wiking Division was in the center of it, including putting down the Warsaw Uprising in the fall of 1944.

Just last year, a former member of the Wiking Division was charged with atrocities:

A 90-year-old former member of an elite Waffen SS unit has been charged with killing 58 Hungarian Jews who were forced to kneel beside an open pit before being shot and tumbling into their mass grave.

The man, named in the German press as Adolf Storms, becomes the latest pensioner to be prosecuted for alleged Nazi war crimes as courts rush to secure convictions before the defendants become too infirm and the witness testimony too unreliable.

Mr Storms was found by accident last year, as part of a research project by Andreas Forster, a 28-year-old student at the University of Vienna. . . .

Mr Storms was a member of the 5th Panzer Wiking Division which fought on the Eastern Front, moving through Ukraine into the Caucasus, taking part in a bloody fight for Grozny and the tank battles of Kharkov and Kursk before wheeling back through Eastern Europe. By most accounts it left a trail of bodies behind.

By the spring of 1945 the unit was heading to Austria with the intention of surrendering to the Americans rather than to the Red Army.

But first the Wiking Division, led in the early days by General Felix Steiner, who is still revered among neo-Nazis, decided to clean up the evidence against it and eliminate the slave labourers who had dug its fortifications and defensive lines.

According to a statement issued by the regional court in Duisburg, where Mr Storms has spent most of his retirement, 57 of the 58 victims were killed near the Austrian village of Deutsch Schuetzen. The mass grave there was excavated in 1995 by the Austrian Jewish association and the bodies given proper funerals.

Storms died in June 2010, before he could go to trial.

Robert M. Citino of the Military History Center at the University of North Texas, hit the nail on the head when he pointed to what he sees as “an adolescent crush” on Nazi history. He goes on to summarize it nicely in a short essay on HistoryNet:

What you often hear is that the [Wiking] division was never formally accused of anything, but that’s kind of a dodge. The entire German war effort in the East was a racial crusade to rid the world of ‘subhumans,’ Slavs were going to be enslaved in numbers of tens of millions. And of course the multimillion Jewish population of Eastern Europe was going to be exterminated altogether. That’s what all these folks were doing in the East. It sends a shiver up my spine to think that people want to dress up and play SS on the weekend.

I don’t buy for a moment that these reenactors are naive innocents who had no idea that their weekend warrior games were simply beyond the pale of polite company; their reenactor website clearly shows otherwise. It’s been heavily scrubbed in the last few days — including removal of event pictures dating back to Iott’s time with them — but archived copies are still available, including this one from August 2007, the year Iott reportedly was last a participant. None of the reenactors are identified by their real names, including the Wiking group’s public contacts. Iott is included as “Reinhard Pferdmann,” and all the other group member identify only under similar alter-ego names. They are hiding, because they know, they understand, how offensive their identification with the Wiking Division is, and they don’t want to have to answer for it. I’ve known a lot of reenactors, and visited lots of reenactor websites, and never encountered one (including Confederate reenactors) who didn’t identify at least the key members of the group publicly. To me, that’s prima facie evidence that these guys knew very well how their hobby was perceived by the public at large, and (unlike most reenactors) very clearly didn’t want to be publicly associated with it. Iott and his buddies know damn well what they’re doing, and why it’s deeply offensive to so many; that’s why they cower behind names like “Reinhard Pferdmann.” Unlike the Waffen-SS men they so admire, these modern reenactors clearly lack the courage of their convictions.

Twenty-some years ago a Civil War reenactor I knew– he was part of a Union artillery battery — cautioned me that “Civil War reenacting is the lunatic fringe of living history.” His observation was tongue-in-cheek, but endearing. I’ve known a lot of reenactors over the years, and often toyed with the idea of diving into the hobby myself. (Much to the relief of both my wife and my wallet, the feeling passes after a few days.) Reenacting has a lot of appeal, and I think it lends itself well to helping educate the public in certain areas. Reenactors particularly excel in explaining the details of daily life, civilian and military, in earlier times. While it seems unlikely that I’ll be putting on a period uniform myself, I get the appeal, and I understand how folks become so devoted to it.

But there’s something fundamentally different about what Iott and his buddies are up to. They are not exploring their own nation’s history, or their family’s, as many Civil War reenactors are. Their open admiration for the Waffen SS — specifically, a Waffen SS division composed of men who betrayed their own fellow Dutch, Belgian, Norwegian citizens and went over to the enemy — is simply unfathomable. (Later in the war, from 1943 on, some Waffen SS men were conscripted from the occupied countries.) It is reprehensible, and they know it; that’s why they hide behind character names. There are thousands of survivors of the Holocaust and Nazi atrocities on the Eastern Front still living, and millions more of their relatives and friends who have heard firsthand of their experiences and the hands of the Waffen SS and others like them. The Wiking reenactors don’t particularly care about those things, or even acknowledge them; they want to focus entirely on their ehrfurcht gebietend MG42 machine guns — “we also have full automatic weapons for rent!” — and downloadable food tin labels. The people aren’t doing history, or education; they’re getting their jollies at playing at being Nazis. They give living history and historical reenacting a bad name. That they don’t own up to their identities online shows that, on some level, they’re embarrassed by what they do. As they should be.

If Rich Iott wants to play dress-up as a member of the Waffen SS, an organization that was declared criminal at the Nuremberg Trials, and simulate a unit that has been implicated in numerous war crimes, then he is free to do so. The rest of us are free to call him out for it. They want to run around playing Waffen-SS, but not be held accountable for it, individually or as a group. Note to the Wiking kameraden; if your hobby is such an embarrassment that you don’t want others to know about it, do us all a favor and get another damned hobby.

Old Dominion Shows the Way

Bloggers Ta-Nehisi Coates and Kevin Levin both call attention to Virginia Governor Bob McDonnell’s announcement Friday that next spring, Confederate History Month will be replaced by Civil War in Virginia Month. This is not only good news, but the governor also chose to make his announcement at the highest-profile venue possible, the 2010 Signature Conference of the Virginia Sesquicentennial of the American Civil War Commission.

The legacies of the Civil War still have the potential to divide us. But there is a central lesson of that conflict that must bond us together today. Until the Civil War, the founding principle that all people are created equal and endowed by their Creator with unalienable rights was dishonored by slavery. Slavery was an evil and inhumane practice which degraded people to property, defied the eternal truth that all people are created in the image and likeness of God, and left a stain on the soul of this state and nation. For this to be truly one nation under God required the abolition of slavery from our soil. Until the Emancipation Proclamation was issued and the Civil War ended, our needed national reconciliation could not begin. It is still a work in progress.

150 years is long enough for Virginia to fight the Civil War.

“Now, on the eve of this anniversary, is a time for us to approach this period with a renewed spirit of goodwill, reverently recalling its losses, eagerly embracing its lessons, and celebrating the measure of unity we have achieved as a diverse nation united by the powerful idea of human freedom.

A modern Virginia has emerged from her past strong, vibrant and diverse. Now, a modern Virginia will remember that past with candor, courage and conciliation. . . .

It’s time to discuss openly how we as Americans, black, white and brown can promote greater reconciliation and trust and greater access to the American Dream for all, so that there is more peace in our hearts and homes, schools and neighborhoods.

This speech is direct, comprehensive, and eloquent. In this address, Bob McDonnell acknowledges and embraces the fundamental truth that so many are unwilling to — that one cannot separate Confederate history from the Civil War, nor the Civil War from this nation’s long, dark legacy of slavery. They are all aspects of the same heritage we share, inextricably intertwined and knotted together.

I have been critical of McDonnell’s original Confederate History Month proclamation — “tone deaf” is about the most charitable thing one can say about it — but today’s remarks really do clean the slate. And while the governor certainly caught a lot of (well-deserved) hell for that earlier document, I’m not going to take a cynical view of his motivations in reversing course here. As Coates said, “You can not ask politicians to do the right thing, and then attack them for doing it.” Amen.

Good for Bob McDonnell. Good for Virginia. Good for the South, and good for our nation. I hope that in this area, has it has so often throughout American history, Virginia sets an example for others to follow.

Added Monday, September 27: Via TPMMuckraker, the SCV responds to McDonnell’s move:

“Our organization is terribly disappointed by this action,” [Virginia SCV Division Commander Brag] Bowling told TPMmuckraker. “[McDonnell] succumbed to his critics, people who don’t support him anyway. And the vast majority of citizens of Virginia support Confederate History Month.”

He said he had spoken with the governor’s office and told them the same thing. He said “Civil War In Virginia Month” is a poor substitute.

“Nobody’s ever been able to reason with me and tell me why we’re honoring Yankees in Virginia,” Bowling said. “The only northerners in Virginia were the ones that came to Virginia and killed thousands of Virginia citizens when they invaded.”

I suppose it’s too much to ask for the SCV to actually respond to the detailed and specific content of McDonnell’s address; instead Bowling drags out the same tired dog-whistles about Yankees and “invasion.” Seriously, folks: get yourselves some new talking points.

Full text of the governor’s address after the jump.

10 comments