“We have received provocation enough. . . .”

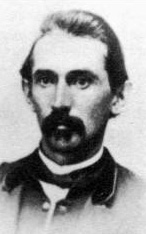

On the first day of July 1863, Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet (left), writing through his adjutant, ordered General George Pickett to bring up his corps from the rear to reinforce the main body of the Army of Northern Virginia. The lead elements of the armies of Robert E. Lee and George Meade had come together outside a small Pennsylvania market town called Gettysburg. The clash there would become the most famous battle of the American Civil War, and would be popularly regarded as a critical turning point not just of that conflict, but in American history. More about Longstreet’s order shortly.

On the first day of July 1863, Confederate Lieutenant General James Longstreet (left), writing through his adjutant, ordered General George Pickett to bring up his corps from the rear to reinforce the main body of the Army of Northern Virginia. The lead elements of the armies of Robert E. Lee and George Meade had come together outside a small Pennsylvania market town called Gettysburg. The clash there would become the most famous battle of the American Civil War, and would be popularly regarded as a critical turning point not just of that conflict, but in American history. More about Longstreet’s order shortly.

I was thinking about the central role of the Battle of Gettysburg in our memory of the war when I recently read an essay by David G. Smith, “Race and Retaliation: The Capture of African Americans During the Gettysburg Campaign,” part of Virginia’s Civil War, edited by Peter Wallenstein and Bertram Wyatt-Brown. All but the last page and a few citations is available online through Google Books.

It’s not a pleasant read.

Research Exercise: “Sam Cullom, Black Confederate”

The name Sam Cullom is a new one to me, but it seems he’s been celebrated in and around Livingston, Tennessee as a local Black Confederate for a while. A military-style headstone was placed over his grave about ten years ago (right), with the legend, “Pvt. Sam Cullom.” His story is told a number of places, like this 2008 piece in the Crossville, Tennessee Chronicle:

The name Sam Cullom is a new one to me, but it seems he’s been celebrated in and around Livingston, Tennessee as a local Black Confederate for a while. A military-style headstone was placed over his grave about ten years ago (right), with the legend, “Pvt. Sam Cullom.” His story is told a number of places, like this 2008 piece in the Crossville, Tennessee Chronicle:

So here’s an assignment for those who may be so inclined. See what you can find in the way of historical documentation that supports or refutes this profile of Cullom. To get you started, here’s his 1921 pension application from the State of Tennessee, and his listing in the decennial U.S. Census for 1880, 1900, 1910 and 1920 (two pages).

Please feel to post links to other, primary sources that are useful in documenting Cullom’s life. Have fun.

“They constitute a privileged class in the community”

![]()

In January 1865 the debate over whether to arm slaves in a last-ditch defense against the Union army was coming to a head in Richmond. The measure would eventually pass a few weeks later, in mid-March. Nonetheless, the Atlanta Southern Confederacy, publishing in Macon, continued to reject the notion that African American should, or even could, be put under arms.

![]()

Keep in mind that on the date this was published, January 20, 1865, Uncle Billy’s troops were marching north from Savannah into South Carolina, Fort Fisher had just been captured, closing the last Confederate port on the Atlantic, and U.S. Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax was lobbying hard for votes to pass the 13th Amendment in Congress. Yet down in Macon, the local editor was devoting column inches to explaining how slaves were a “privileged class,” happy and contented folks, unburdened by anxiety or want: “how happy we should be were we the slave of some good and provident owner.”

You may bang your head on the desk now.

____________

[1] Atlanta Southern Confederacy, January 20, 1865. Quoted in Robert F. Durden, The Gray and the Black: The Confederate Debate on Emancipation (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1972), 156-58. Image: “Market Scene in Macon, Georgia,” by A. R. Waud. From here.

Hari Jones Drops the Hammer on National Observance of Juneteenth

[This post originally appeared on June 20, 2011.]

Hari Jones, Curator of the African American Civil War Museum, drops the hammer on the movement to make Juneteenth a national holiday, and the organization behind it, the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation (NJoF). He argues that the narrative used to justify the propose holiday does little to credit African Americans with taking up their own struggle, and instead presents them as passive players in emancipation, waiting on the beneficence of the Union army to do it for them. Further, he presses, the standard Juneteenth narrative carries forward a long-standing, intentional effort to suppress the story of how African Americans, in ways large and small, worked to emancipate themselves, particularly by taking up arms for the Union. He wraps up a stem-winder:

Certainly, informed and knowledgeable people should not celebrate the suppression of their own history. Juneteenth day is a de facto celebration of such suppression. Americans, especially Americans of African descent, should not celebrate when the enslaved were freed by someone else, because that’s not the accurate story. They should celebrate when the enslaved freed themselves, by saving the Union. Such freedmen were heroes, not spectators, and their story is currently being suppressed by the advocates of the Juneteenth national holiday. The Emancipation Proclamation did not free the slaves; it made it legal for this disenfranchised, enslaved population to free themselves, while maintaining the supremacy of the Constitution, and preserving the Union. They became the heroes of the Republic. It is as Lincoln said: without the military help of the black freedman, the war against the South could not have been won. That’s worth celebrating. That’s worth telling. The story of how Americans of African descent helped save the Union, and freed themselves. Let’s celebrate the truth, a glorious history, a story of a glorious march to Liberty.

![]()

Jones makes a powerful argument, with solid points. But I think he misses something crucial, which is that in Texas, where Juneteenth originated, it’s been a regular celebration since 1866. It is not a modern holiday, established retroactively to commemorate an event in the long past; the celebration of Juneteenth is as old as emancipation itself. It was created and carried on by the freedmen and -women themselves:

![]()

Some of the early emancipation festivities were relegated by city authorities to a town’s outskirts; in time, however, black groups collected funds to purchase tracts of land for their celebrations, including Juneteenth. A common name for these sites was Emancipation Park. In Houston, for instance, a deed for a ten-acre site was signed in 1872, and in Austin the Travis County Emancipation Celebration Association acquired land for its Emancipation Park in the early 1900s; the Juneteenth event was later moved to Rosewood Park. In Limestone County the Nineteenth of June Association acquired thirty acres, which has since been reduced to twenty acres by the rising of Lake Mexia. Particular celebrations of Juneteenth have had unique beginnings or aspects. In the state capital Juneteenth was first celebrated in 1867 under the direction of the Freedmen’s Bureau and became part of the calendar of public events by 1872. Juneteenth in Limestone County has gathered “thousands” to be with families and friends. At one time 30,000 blacks gathered at Booker T. Washington Park, known more popularly as Comanche Crossing, for the event. One of the most important parts of the Limestone celebration is the recollection of family history, both under slavery and since. Another of the state’s memorable celebrations of Juneteenth occurred in Brenham, where large, racially mixed crowds witness the annual promenade through town. In Beeville, black, white, and brown residents have also joined together to commemorate the day with barbecue, picnics, and other festivities.

![]()

It’s one thing to argue with another historian or community leader about the the historical narrative represented by a public celebration (think Columbus Day), but it’s entirely another to — in effect — dismiss the understanding of the day as originally celebrated by the people who actually lived those events, and experienced them at first hand.

What do you think?

_____________

h/t Kevin. Image: Juneteenth celebration in Austin, June 19, 1900. PICA 05476, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Juneteenth, History and Tradition

[This post originally appeared here on June 19, 2010.]

“Emancipation” by Thomas Nast. Ohio State University.

![]()

Juneteenth has come again, and (quite rightly) the Galveston County Daily News, the paper that first published General Granger’s order that forms the basis for the holiday, has again called for the day to be recognized as a national holiday:

Those who are lobbying for a national holiday are not asking for a paid day off. They are asking for a commemorative day, like Flag Day on June 14 or Patriot Day on Sept. 11. All that would take is a presidential proclamation. Both the U.S. House and Senate have endorsed the idea. Why is a national celebration for an event that occurred in Galveston and originally affected only those in a single state such a good idea? Because Juneteenth has become a symbol of the end of slavery. No matter how much we may regret the tragedy of slavery and wish it weren’t a part of this nation’s story, it is. Denying the truth about the past is always unwise. For those who don’t know, Juneteenth started in Galveston. On Jan. 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. But the order was meaningless until it could be enforced. It wasn’t until June 19, 1865 — after the Confederacy had been defeated and Union troops landed in Galveston — that the slaves in Texas were told they were free. People all across the country get this story. That’s why Juneteenth celebrations have been growing all across the country. The celebration started in Galveston. But its significance has come to be understood far, far beyond the island, and far beyond Texas.

![]()

This is exactly right. Juneteenth is not just of relevance to African Americans or Texans, but for all who ascribe to the values of liberty and civic participation in this country. A victory for civil rights for any group is a victory for us all, and there is none bigger in this nation’s history than that transformation represented by Juneteenth.

But as widespread as Juneteenth celebrations have become — I was pleased and surprised, some years ago, to see Juneteenth celebration flyers pasted up in Minnesota — there’s an awful lot of confusion and misinformation about the specific events here, in Galveston, in June 1865 that gave birth to the holiday. The best published account of the period appears in Edward T. Cotham’s Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, from which much of what follows is abstracted.

The United States Customs House, Galveston.

![]()

On June 5, Captain B. F. Sands entered Galveston harbor with the Union naval vessels Cornubia and Preston. Sands went ashore with a detachment and raised the United States flag over the federal customs house for about half an hour. Sands made a few comments to the largely silent crowd, saying that he saw this event as the closing chapter of the rebellion, and assuring the local citizens that he had only worn a sidearm that day as a gesture of respect for the mayor of the city.

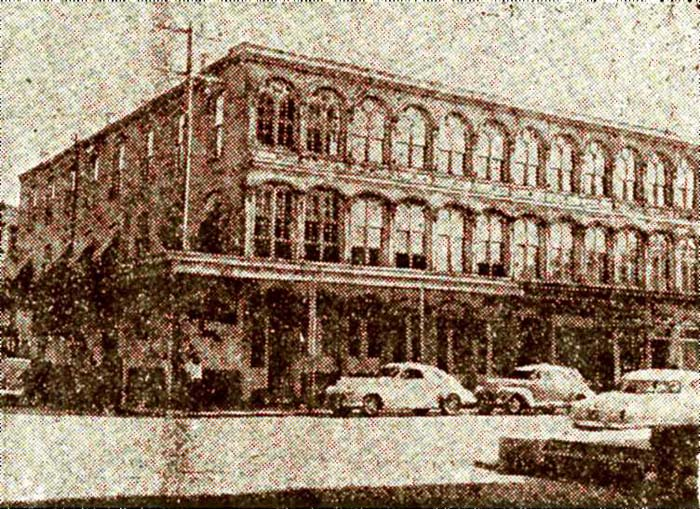

The 1857 Ostermann Building, site of General Granger’s headquarters, at the southwest corner of 22nd Street and Strand. Image via Galveston Historical Foundation.

![]()

A large number of Federal troops came ashore over the next two weeks, including detachments of the 76th Illinois Infantry. Union General Gordon Granger, newly-appointed as military governor for Texas, arrived on June 18, and established his headquarters in Ostermann Building (now gone) on the southwest corner of 22nd and Strand. The provost marshal, which acted largely as a military police force, set up in the Customs House. The next day, June 19, a Monday, Granger issued five general orders, establishing his authority over the rest of Texas and laying out the initial priorities of his administration. General Orders Nos. 1 and 2 asserted Granger’s authority over all Federal forces in Texas, and named the key department heads in his administration of the state for various responsibilities. General Order No. 4 voided all actions of the Texas government during the rebellion, and asserted Federal control over all public assets within the state. General Order No. 5 established the Army’s Quartermaster Department as sole authorized buyer for cotton, until such time as Treasury agents could arrive and take over those responsibilities.

It is General Order No. 3, however, that is remembered today. It was short and direct:

Headquarters, District of Texas

Galveston, Texas, June 19, 1865 General Orders, No. 3 The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere. By order of

Major-General Granger

F. W. Emery, Maj. & A.A.G.

![]()

What’s less clear is how this order was disseminated. It’s likely that printed copies were put up in public places. It was published on June 21 in the Galveston Daily News, but otherwise it is not known if it was ever given a formal, public and ceremonial reading. Although the symbolic significance of General Order No. 3 cannot be overstated, its main legal purpose was to reaffirm what was well-established and widely known throughout the South, that with the occupation of Federal forces came the emancipation of all slaves within the region now coming under Union control.

The James Moreau Brown residence, now known as Ashton Villa, at 24th & Broadway in Galveston. This site is well-established in recent local tradition as the site of the original Juneteenth proclamation, although direct evidence is lacking.

![]()

Local tradition has long held that General Granger took over James Moreau Brown’s home on Broadway, Ashton Villa, as a residence for himself and his staff. To my knowledge, there is no direct evidence for this. Along with this comes the tradition that the Ashton Villa was also the site where the Emancipation Proclamation was formally read out to the citizenry of Galveston. This belief has prevailed for many years, and is annually reinforced with events commemorating Juneteenth both at the site, and also citing the site. In years past, community groups have even staged “reenactments” of the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation from the second-floor balcony, something which must surely strain the limits of reasonable historical conjecture. As far as I know, the property’s operators, the Galveston Historical Foundation, have never taken an official stand on the interpretation that Juneteenth had its actual origins on the site. Although I myself have serious doubts about Ashton Villa having having any direct role in the original Juneteenth, I also appreciate that, as with the band playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee” as Titanic sank beneath the waves, arguing against this particular cherished belief is undoubtedly a losing battle.

Assuming that either the Emancipation Proclamation (or alternately, Granger’s brief General Order No. 3) was formally, ceremonially read out to the populace, where did it happen? Charles Waldo Hayes, writing several years after the war, says General Order No. 3 was “issued from [Granger’s] headquarters,” but that sounds like a figurative description rather than a literal one. My bet would not be Ashton Villa, but one of two other sites downtown already mentioned: the Ostermann Building, where Granger’s headquarters was located and where the official business of the Federal occupation was done initially, or at the United States Customs House, which was the symbol of Federal property both in Galveston and the state as a whole, and (more important still) was the headquarters of Granger’s provost marshal, Lieutenant Colonel Rankin G. Laughlin (right, 1827-78) of the 94th Illinois Infantry. It’s easy to imagine Lt. Col. Laughlin dragging a crate out onto the sidewalk in front of the Customs House and barking out a brief, and somewhat perfunctory, read-through of all five of the general’s orders in quick succession. No flags, no bands, and probably not much of a crowd to witness the event. My personal suspicion is that, were we to travel back to June 1865 and witness the origin of this most remarkable and uniquely-American holiday, we’d find ourselves very disappointed in how the actual events played out at the time.

Assuming that either the Emancipation Proclamation (or alternately, Granger’s brief General Order No. 3) was formally, ceremonially read out to the populace, where did it happen? Charles Waldo Hayes, writing several years after the war, says General Order No. 3 was “issued from [Granger’s] headquarters,” but that sounds like a figurative description rather than a literal one. My bet would not be Ashton Villa, but one of two other sites downtown already mentioned: the Ostermann Building, where Granger’s headquarters was located and where the official business of the Federal occupation was done initially, or at the United States Customs House, which was the symbol of Federal property both in Galveston and the state as a whole, and (more important still) was the headquarters of Granger’s provost marshal, Lieutenant Colonel Rankin G. Laughlin (right, 1827-78) of the 94th Illinois Infantry. It’s easy to imagine Lt. Col. Laughlin dragging a crate out onto the sidewalk in front of the Customs House and barking out a brief, and somewhat perfunctory, read-through of all five of the general’s orders in quick succession. No flags, no bands, and probably not much of a crowd to witness the event. My personal suspicion is that, were we to travel back to June 1865 and witness the origin of this most remarkable and uniquely-American holiday, we’d find ourselves very disappointed in how the actual events played out at the time.

Maybe the Ashton Villa tradition is preferable, after all.

![]()

Update, June 19: Over at Our Special Artist, Michele Walfred takes a closer look at Nast’s illustration of emancipation.

![]()

Update 2, June 19: Via Keith Harris, it looks like retiring U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison supports a national Juneteenth holiday, too. Good for her.

![]()

Update 3, June 19, 2013: Freedmen’s Patrol nails the general public’s ambivalence about Juneteenth:

![]()

![]()

Exactly right.

______________

The (Very) Posthumous Enlistment of “Private” Clark Lee

Kevin and Brooks have been all over the Georgia Civil War Commission, and particularly of its handling of the case of Clark Lee, “Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier.” I won’t rehash all of that, but there are a few points to add.

Kevin and Brooks have been all over the Georgia Civil War Commission, and particularly of its handling of the case of Clark Lee, “Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier.” I won’t rehash all of that, but there are a few points to add.

First, kudos to Eric Jacobson, who noticed that the modern painting of Lee used by the commission on its marker (right) is almost laughably tailored to affirm Lee’s status as a soldier, including the military coat with trim and brass buttons, rifle, cartridge box belt, military-issue “CS” belt buckle, and revolver, all backed by a Confederate Battle Flag — even though the Army of the Tennessee didn’t adopt that flag until the appointment of General Joseph E. Johnston, well after the Battle of Chickamauga.

It’s probably also worth noting that the man in the painting looks a lot older than 15, the age the Georgia Civil War Commission says Lee was at the time of the battle.

As it turns out, several weeks ago the SCV and other heritage folks installed and dedicated a new headstone for Lee, explicitly (and posthumously) giving him the military rank of Private. The stone also states that Lee “fought at” Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain, the Atlanta Campaign, and a host of other engagements by the Army of Tennessee. These are very specific claims, so it’s worth asking what the specific evidence for them is.

![]()

E. Raymond Evans (center, with umbrella), author of The Life and Times of Clark Lee: Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier, speaking at an SCV memorial service for Clark Lee in April 2013. From here.

![]()

As is so often the case, there doesn’t appear to be any contemporary (1861-65) record of Lee’s service. There is no compiled service record (CSR) for him at the National Archives. Presumably the historical marker, the headstone, and a recent privately-published work on Clark Lee are all based on his 1921 application for a pension from the State of Tennessee, where he had moved in the years after the war. You can read Lee’s complete pension application here (29MB PDF). I cannot find a word in it that mentions or describes Clark Lee’s service under arms, or in combat. There is a general description of Lee’s wartime activities, but it’s quite different from what the Georgia Civil War Commission wants the rest of us to understand about him. I’ve put it below the jump because of some of the unpleasant themes expressed.

Call for Historical Marker to Recognize Slave Labor

![]()

My friend and colleague Jim Schmidt had a great guest column in Saturday’s Galveston County Daily News:

![]()

150 Years Ago: Isle Needs marker to Honor Civil War Slaves

By JAMES M. SCHMIDT

The New Year’s Day 1863 Battle of Galveston was undoubtedly the zenith of the island’s Civil War story, but it was by no means the end.More than two years of fighting remained and in many ways they were the worst of the war for those who remained on the island: soldiers, the few remaining citizens, and hundreds of enslaved African-Americans, who worked — and died — building fortifications. That slaves did the lion’s share of the work in constructing the Galveston defenses was nothing new: slaves had actually built fortifications in the early days of Galveston during the Texas Revolution. The first call for slave labor on behalf of the Confederate forces in Galveston may have been as early as November 1861, when Gen. Paul Hebert authorized an aide on his staff to induce local planters “to assist in the erection of fortifications for the defense of the coast, in loaning their Negroes (sic) for that purpose.” Likewise, in April 1862, Gen. William R. Scurry declared that “it is absolutely necessary that every preparation for defense should be made to protect Texas from invasion. … In a short time, with Negroes to work on the fortifications, the Island can be made impregnable, and the State saved from the pol(l) uting tread of armed abolitionists.” To that end he called on planters in 20 counties to “send at once one-fourth of their male Negro population … with spades and shovels … to report to Galveston.” It was after the Battle of Galveston, though, that the work began in earnest. Indeed, only days later, a Confederate soldier wrote his wife that he expected that his unit would be permanently located in Galveston, and added with just confidence, “unless the Federals whip us out, which they are not likely to do.” His work was now devoted to securing the recaptured island, and he added: “In a few days we will have this place well-fortified. There are several hundred Negroes here at work building new fortifications and repairing those already built.” In April 1863, Col. Valery Sulakowski, the supervising engineer, reported that more than 600 enslaved African-Americans were engaged at the saw mills — carrying sod, timber and iron — and cooking or working on harbor and gulf defenses. The officer called for hundreds more, but getting additional slave labor was no easy task: Texas planters routinely volunteered insufficient numbers of their slaves to the periodic calls. It is no wonder they were reluctant: archival hospital records show that many slaves died from disease, exhaustion or injuries suffered while constructing the Galveston defenses. The slaves themselves did not leave a record of their toil, but the work left at least one young girl without a father. In a 1930s interview, Philles Thomas, born into slavery in Texas, explained, “I can’t ’member my daddy, but mammy told me him am sent to de ‘Federate Army an am kilt in Galveston.” Perhaps the time has come to install a historical marker to commemorate the slaves who labored — and died — on the island during the Civil War. _______

James M. Schmidt is a research scientist with a biotech firm in The Woodlands. He is a contributor, editor or author of five books on the Civil War, including, most recently, Galveston and the Civil War: An Island City in the Maelstrom, The History Press, 2012.

_______

James M. Schmidt is a research scientist with a biotech firm in The Woodlands. He is a contributor, editor or author of five books on the Civil War, including, most recently, Galveston and the Civil War: An Island City in the Maelstrom, The History Press, 2012.

___________

Image: Impressed slaves building fortifications at James Island, South Carolina. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Norris White, Black Confederate “Brothers” and the “Flipside” to Glory

A while back, Kevin highlighted a news item on Norris White, Jr., a graduate student at Stephen F. Austin State University who was making the rounds last year, doing presentations and generally talking up the subject of African American soldiers in the Confederate army. Norris White seems to be serious and well-intentioned, and (thankfully) he’s no stream-of-consciousness performance artist like Edgerton. But being sincere is not the same thing as being right. For all his insistence that he’s using primary sources, White’s interviews seem to be little more than reiterating black Confederate rhetoric that the SCV has been asserting for years. While he insists on the importance of primary source materials — “100 percent irrefutable evidence — letters, diaries, pension applications, photographs, newspaper accounts, county commission records and other evidence” — there’s little indication that he’s looked carefully at the materials, or understands them in the larger context of the war and the decades that followed. It’s very shallow stuff he’s doing, hand-waving at a pile of reunion photographs, pension records and loose anecdotes and saying, “see? Black Confederates!” Anyone can do that, and plenty of people do.

It says a lot about the depth of his research that in interviews, White has repeatedly singled out two Texas Historical Commission markers as evidence of his much larger claims about “Black Texans who served in the Confederate Army.” These markers, one to Randolph Vesey (Wise County) and the the other to Primus Kelly (Grimes County), are worth closer examination for what they say, and what they don’t. I obtained copies of the historical marker files for both markers, that you can dowload here (Vesey) and here (Kelly). Both men, as was usual at the time the markers were set up, were explicitly and effusively lauded for their loyalty and sacrifice not to the Confederacy but as (in the case of Kelly), “a faithful Negro slave,” right there in the very first line of the marker.

The files are thin — the THC was less diligent about documentation in past decades than they are now — but neither file contains any contemporary documentation of its subject at all. Both amount to a recording of local oral tradition, which is vivid not though always reliable. Both accounts make it explicitly clear that the two men went to war as personal servants, Vesey to General William Lewis Cabell, and Kelly to the West brothers, troopers in the Eighth Texas Cavalry. But it’s very thin stuff to spin into a claim that “the number of black Texans who participated in the Confederate Army in the War Between the States may have been as high as 50,000,” which would be a figure substantially higher than the entire male slave population of Texas between ages 15 and 50 in 1860, which was a bit under 44,000. Claims like that on White’s part seriously undermine his credibility.

Vesey’s and Kelly’s stories, as reflected in the marker files, are well worth reading, and telling. In Vesey’s case, his wartime experiences with General Cabell probably paled in comparison with his being captured by Indians a few years later and being held prisoner for three months, until his release was secured by one of the legendary characters of the Texas frontier during that time, Britt Johnson.

Primus Kelly’s marker file, though, is much more interesting from the perspective of the advocacy for black Confederates, because included in the file is a 1990 article by Jeff Carroll on Vesey from Confederate Veteran magazine, the official publication of the SCV. The magazine article is a reprint of an article that first appeared in the Midlothian, Texas Mirror on May 31, 1990. Kevin has often suggested that the Confederate Heritage™ groups’ push to find black Confederates in the 1990s was, in part, a reaction to the success of the film Glory (1989), and its depiction of both African American Union soldiers. In light of that, it’s significant that Carroll’s article was originally published just six weeks after Denzel Washington won an Oscar for his role as Private Trip in that film, and moreover, was explicitly framed by its author as the “flipside” to that work:

![]()

There’s no indication that Carroll referenced any materials on Kelly other than the text of the marker itself, but he embellishes that text with all sorts of assertions that are completely unsupported. Take, for example, this passage from the marker:

![]()

![]()

In Carroll’s retelling, this becomes:

![]()

![]()

There’s a world of difference between “West sent Kelly” and “Primus refused to stay at home,” but it’s entirely typical of the way advocates like Carroll depict African American men’s involvement with the Confederate army; it’s always shown as voluntary choice, motivated by noble intent, never out of legal obligation or against their wishes.

The is no evidence in the historical marker files of Kelly’s relationship with the West sons, much less the suggestion that they were “constant companions.” Carroll begins his essay by making the generalized claim that “custom often dictated that the sons of a slave owner received as their own property and slaves of their own age when they’ were children. They were daily and inseparable companions who shared the experience of growing up and became surrogate brothers,” and then paints that assertion right across Primus Kelly. He characterizes Kelly’s relationship with the Wests as that of “brothers” three more times in five short paragraphs, based (as far as I can tell) on no evidence whatsoever. We’ve seen claims like these made falsely before.

![]()

![]()

It’s also highly unlikely that Primus Kelly would have been an “inseparable companion” to any of the West brothers, given the difference in their ages. According to the 1870 U.S. Census (above), Primus Kelly was born about 1847, making him much younger than Robert (age 22 upon enlistment in 1861, giving him a birthdate of c. 1839), John (age 27 upon enlistment in 1861, birthdate c. 1834), or Richard (age 32 upon discharge in January 1863, birthdate c. 1831). Primus Kelly was about eight years younger than the youngest of the Wests, and in fact was barely into his teens when he accompanied the Wests off to war. He was not a childhood companion of any of these men, and the three brothers were living at Lynchburg in Harris County — almost 100 miles away from their father in Grimes County — at the time of the 1860 census.

Carroll’s description of the Wests is somewhat misleading, as well. According to the marker, Richard was reportedly wounded twice in battle and escorted all the way back to Texas by Kelly. Carroll repeats this claim, without question. But if this happened, neither wound is recorded in his compiled service record at NARA. What is recorded is that Richard was given a medical discharge for chronic illness not related to combat injuries in January 1863, nine months after enlisting. It seems very unlikely that during those nine months, Richard West would have been twice wounded so severely that he required an extended convalescence back home in Texas, and made the round journey twice, without there being a record of it in his file.

The three brothers did not enlist together, as Carroll suggests; Robert and John, ages 22 and 27 respectively, enlisted in September 1861, when the regiment was first being organized, while their older brother Richard, age 31 or 32, didn’t join the regiment until May of 1862. Carroll cites Chickamauga (September 1863) and Knoxville (November/December 1863) as fights in which Terry’s Rangers participated, but only Robert might have been present, as he was taken prisoner sometime during the latter part of 1863. Richard was medically discharged, and John was dead. Robert died in April 1905, his obituary appearing in the Confederate Veteran magazine in July of that year.

Kelly is said to have followed the Wests into action, “firing his own musket and cap and ball pistol.” There are many such anecdotes from the war, and they may well be true in Kelly’s case. There is a report in the OR (Series I, Vol. XVI, Part 1, p. 805) by a Union officer from the Battle of Murfreesboro, July 1862, that “The forces attacking my camp were the First [sic., Eighth] Regiment Texas Rangers, Colonel Wharton, and a battalion of the First Georgia Rangers. . . . There were also quite a number of negroes [sic.] attached to the Texas and Georgia troops, who were armed and equipped, and took part in the several engagements with my forces during the day.” But if this is one of the events that Kelly participated in, it underscores the argument that those men were camp servants following their troopers into action, rather than troopers in their own right.

Did Carroll set out to fictionalize Primus Kelly’s story? I don’t know, but to all intents and purposes that was the result. The end product is as much happy fantasy as fact. And even then, it wouldn’t matter so much were it not that other authors have gone on to cite Carroll, including Kelly Barrow’s Black Confederate. In fact, the article is a mess, in which even knowable, factual information is misrepresented. Under the circumstances, I actually think there is one other thing that this article could appropriately borrow from Glory, and it comes right at the very, very end of the movie:

![]()

This story is based upon actual events and persons.

However, some of the characters and incidents portrayed

and the names herein are fictitious, and any similarity

to the name, character, history of any person,

living or dead, or any actual event is entirely

coincidental and unintentional.

![]()

![]()

Like so much else that’s been written about black Confederates in the last 23 years, Jeff Carroll’s article takes a kernel of fact, churns it in a bucket with inaccurate or flat-out-false information and untethered speculation, to create a warm-and-fuzzy story that reassures the Confederate Heritage™ crowd that it was all good, and there’s nothing particularly troubling or complex about any of it — because, you know, they were like brothers. The thing that’s notable about it is that (1) it’s undoubtedly one of the earliest of its type, (2) it’s offered explicitly as a corrective to the narrative presented in Glory, and (3) it so fully expresses the modern talking points that define the push to relabel men who used to be called (as in Kelly’s case) “a faithful Negro slave,” into something far more palatable for modern audiences.

I understand why people want to believe this happy nonsense; it takes a raw, ugly edge off a time and place they have chosen to embrace tightly. What I don’t understand is how someone like Norris White would fall for it. Unlike most of the folks who peddle this stuff, White presumably has the academic background and the research skills to dig into the weeds of this stuff, and understand what the sources actually say. (A good place to start is acknowledging that an historical marker by the side of the highway is not a primary source.) He has the skills and resources to say something new, but instead repeats the same half-truths that have been circulating for decades.

Please, Mr. White, tell Randolph Vesey’s story, and Primus Kelly’s. But tell them fully and completely. Any damn fool can read off the text of a roadside marker and pretend that’s research. You’re better than that, Mr. White, so show us.

____________

Update:

Bruce Levine’s Fall of the House of Dixie

Bruce Levine’s Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves during the Civil War (2007) is probably the best full-length study the contentious debates within the Confederacy over the question of whether to put enslaved men into the ranks of the army, and how to go about doing that. Though such a plan was eventually approved by the Confederate Congress in mid-March 1865 — three weeks before the evacuation of Richmond, and four weeks before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox — it was nonetheless a hard and bitter pill to swallow. Hard-line Confederate ideologues found the very notion an anathema; Howell Cobb famously called the proposal “the beginning of the end of the revolution.” It was, Cobb argued, a “suicidal policy.”

Bruce Levine’s Confederate Emancipation: Southern Plans to Free and Arm Slaves during the Civil War (2007) is probably the best full-length study the contentious debates within the Confederacy over the question of whether to put enslaved men into the ranks of the army, and how to go about doing that. Though such a plan was eventually approved by the Confederate Congress in mid-March 1865 — three weeks before the evacuation of Richmond, and four weeks before Lee’s surrender at Appomattox — it was nonetheless a hard and bitter pill to swallow. Hard-line Confederate ideologues found the very notion an anathema; Howell Cobb famously called the proposal “the beginning of the end of the revolution.” It was, Cobb argued, a “suicidal policy.”

Levine’s new book, The Fall of the House of Dixie: The Civil War and the Social Revolution That Transformed the South (2013), takes a broader view of the cultural and racial norms of the “peculiar institution,” and how those were upturned by war and Reconstruction. On Monday, Terry Gross interviewed Levine on NPR’s Fresh Air:

![]()

“The black population of the South had been raised on the notion that, among other things, black men could not, of course, be soldiers,” Levine tells Fresh Air‘s Terry Gross, “that black men were not courageous, black men were not disciplined, black men could not act in response in large numbers to military commands, black men would flee at the first opportunity if faced with battle, and the idea that black men in uniform could exist and … offer them the opportunity to disprove these notions and … more importantly, actively struggle to do away with slavery, was unbelievably attractive to huge numbers of black people.” As its ranks dwindled and in a last gasp, the Confederacy, too, had a plan to recruit black soldiers. In 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis approved a plan to recruit free blacks and slaves into the Confederate army. Quoting Frederick Douglass, Levine calls the logic behind the idea “a species of madness.” One factor that contributed to this madness, he says, “is the drumbeat of self-hypnosis” that told Confederates that “the slaves are loyal, the slaves embrace slavery, the slaves are contented in slavery, the slaves know that black people are inferior and need white people to … oversee their lives. … Black people will defend the South that has been good to them. There are, of course, by [then] very many white Southerners who know this is by no means true, but enough of them do believe it so that they’re willing to give this a chance.” Considering what might have happened had there been no war at all, Levine thinks slavery could well have lasted into the 20th century, and that it was, in fact, the Confederacy that hastened slavery’s end. “In taking what they assumed to be a defensive position in support of slavery,” he says, “the leaders of the Confederacy … radically hastened its eradication.”

You can listen to the full, 37-minute interview here, or read the transcript here.

____________ Thanks to Horde member dmf for alerting me to this story.

Private Kirkland, Battery D, First Missouri Light Artillery

A postwar image of part of Wilson’s Creek Battlefield, believed to be the cornfield behind the Ray family springhouse. Image via Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield; WICR 31376.

Like probably a lot of people, I was surprised by the scene in Lincoln where Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln’s modiste and confidante, says to the president, “as for me: my son died, fighting for the Union, wearing the Union blue. For freedom he died. I’m his mother. That’s what I am to the nation, Mr. Lincoln. What else must I be?”

I was unaware that Keckley’s son had died as a Union soldier, but it’s true — at Wilson’s Creek, in 1861. Over at The Sable Arm, Jimmy Price has the details.

___________

29 comments