Peter Phelps Was Not a “Negro in Grey”

Update, May 19.

After I posted this essay George Purvis, the author of the Negroes in Gray website, contacted the TSL again, asking for clarification on Peter Phelps. This was their reply, which he has also posted to the website:

In consulting with colleagues, it was discovered that the list of soldiers and widows believed to be African-American used to answer your previous question had been revised with the deletion of the name Peter Phelps and the addition of two other names.

We agree with your research that Peter Phelps is White. The additional names on the revised list are:

William A. Green Rejected of Burleson County

Turner Armstrong 38653 of Franklin CountyWe apologize for the incorrect information.

So we can call the case of Peter Phelps closed, I guess. For my part, I don’t think the TSL staff has anything to apologize for in this case; what they’d sent originally was an informal list, compiled by their staff over a period of time. It is what it is. It’s up to the rest of us to be careful and diligent consumers of historical information.

![]()

Recently one of the more outspoken online advocates for black Confederate soldiers (BCS) posted a link to a site that purports to list African Americans who, in one way or another, were part of the Confederate military effort during the Civil War. This person, who dismisses ideas like historical context, analysis and interpretation as “opinion” and “biased agenda,” insists that he’s only interested in “facts,” and has compiled this website in that vein. No interpretation, no discussion, no larger context. Just “facts.”

So I went to the Negroes in Grey website and, clicking on the menu at upper left, selected “The States, The People.” A fly-out menu lists several states, including Texas, so I clicked there. Immediately I was presented a transcript of a letter (presumably to the site’s owner) from the staff of the Texas State Library, explaining that they have no comprehensive means of searching for African Americans in their files. They did, however, explain that the staff there had, over a period of years, compiled a list of sixteen applications in which either the applicant or his widow was believed by the staff to be African American, and included in the letter their names, counties and pension numbers. One that jumped out at me right away was Peter Phelps of Galveston County (No. 07720). Being a native of Galveston County myself, I determined to find out more about this guy. Who was Peter Phelps, and was he really a “Negro in Grey?”

Well, no. It turns out that Peter Phelps was a white man who married a mixed-race woman after the war, and it takes about two minutes with readily-available, online records to determine that. So what’s up with this “Negro in Grey” business?

“The color of the white man is now, in the South, a title of nobility.”

A few days ago we posted on the writings of James D. B. DeBow, a publisher and essayist who brought his considerable talents to the denunciation of abolitionism, and the defense of slavery, in the years leading up to the war. In his December 1860 booklet The Interest in Slavery of the Southern Non-Slaveholder, DeBow argued that slavery was not only an economic necessity, but absolutely essential to maintaining an aristocracy of white men that must — always — be above those of African descent, regardless of their economic standing:

The non-slaveholder of the South preserves the status of the white man, and is not regarded as an inferior or a dependant. He is not told that the Declaration of Independence, when it says that all men are born free and equal, refers to the negro equally with himself. It is not proposed to him that the free negro’s vote shall weigh equally with bis own at the ballot-box, and that the little children of both colors shall be mixed in the classes and benches of the school-house, and embrace each other filially in its outside sports. . . . No white man at the South serves another as a body servant, to clean his boots, wait on his table, and perform the menial services of his household. His blood revolts against this, and his necessities never drive him to it. He is a companion and an equal. When in the employ of the slaveholder, or in intercourse with him, he enters his hall, and has a seat at his table. If a distinction exists, it is only that which education and refinement may give, and this is so courteously exhibited as scarcely to strike attention. The poor white laborer at the North is at the bottom of the social ladder, whilst his brother here has ascended several steps and can look down upon those who are beneath him, at an infinite remove.

DeBow was not the only Southern writer to make this argument. At the end of October 1860, South Carolina State Senator John Townsend (1799-1881, right) published a pamphlet, The Doom of Slavery in the Union – Its Safety Out of It. Along with DeBow’s booklet, The Doom of Slavery was one of the most popular secessionist tracts of the day. A few weeks after his pamphlet appeared, Townsend went on to sign of the South Carolina’s Ordinance of Secession. Here, Townsend makes explicit that slavery is not just central to the perpetuation of social order in the South, but the maintenance of a uniquely Southern system of caste:

DeBow was not the only Southern writer to make this argument. At the end of October 1860, South Carolina State Senator John Townsend (1799-1881, right) published a pamphlet, The Doom of Slavery in the Union – Its Safety Out of It. Along with DeBow’s booklet, The Doom of Slavery was one of the most popular secessionist tracts of the day. A few weeks after his pamphlet appeared, Townsend went on to sign of the South Carolina’s Ordinance of Secession. Here, Townsend makes explicit that slavery is not just central to the perpetuation of social order in the South, but the maintenance of a uniquely Southern system of caste:

The Effects to the Non-Slaveh0lder.

We forbear to notice the effect of the abolition of slavery upon the Banks, Insurance Companies, Railroads, and all other corporations, depending upon a rich a and flourishing country for their own prosperity. But in noticing its effects upon the different classes and: interests in the South, we should not omit to notice its effects upon the non-slaveholding portion of our citizens.

Accompanied as that measure is to be, by reducing the two races to an equality—or, in other words, in elevating the negro slave to an equality with the white man—it will be to the non-slaveholder, equally with the largest slaveholder, the obliteration of caste and the deprivation of important privileges. The color of the white man is now, in the South, a title of nobility in his relations as to the negro; and although Cuffy or Sambo may be immensely his superior in wealth, may have his thousands deposited in bank, as some of them have, and may be the owner of many slaves, as some of them are, yet the poorest non-slaveholder, being a white man, is his superior in the eye of the law; may serve and command in the militia; may sit upon juries, to decide upon the rights of the wealthiest in the land ; may give his testimony in Court, and may cast his vote, equally with the largest slaveholder, in the choice of his rulers. In no country in the world does—the poor white man, whether slaveholder or non-slaveholder, occupy so enviable a position as in the slaveholding States of the South. His color here admits him to social and civil privileges, which the white man enjoys nowhere else. In countries where negro slavery does not exist, (as in the Northern States of this Union and in Europe,) the most menial and degrading employments in society are filled by the white poor, who are hourly seen drudging in them. Poverty, then, in those countries, becomes the badge of inferiority, and wealth, ordistinction. Hence the arrogant airs which wealth there puts on, in its intercourse with the poor man. But in the Southern slaveholding States, where these menial and degrading offices are turned over to be per formed exclusively by the negro slave, the status and color of the black race becomes the badge of inferiority, and the poorest non-slaveholder may rejoice with the richest of his brethren of the white race, in the distinction of his color. The poorest non-slaveholder, too, except as I have before said, he be debased by his vices or his crimes, thinks and feels and acts as if he was, and always intended to be, superior to the negro. He may be poor, it is true; but there is no point upon which he is so justly proud and sensitive as his privilege of caste; and there is nothing which he would resent with more fierce indignation than the attempt of the Abolitionist to emancipate the slaves and elevate the negros to an equality with himself and his family. The abolitionists have sent their emissaries among that class of our citizens, trying to debauch their minds by persuading them that they have no interest in preventing the abolition of slavery, But they cannot deceive any, except the most ignorant and worthless, the intelligent among them are too well aware of the degrading consequences of abolition upon themselves and their families (such as I have described them), to be entrapped by their arts. They know that, at the North and in Europe, where no slavery exists, where poverty is the mark of inferiority; where the negros have been put upon equality with the whites, and “money makes the man,” although, —that man may be a negro;—they know, I say, that there the white man is seen waiting upon the negro;—there he is seen obeying the negro as his ostler, his coachman, his servant and his bootblack. Knowing, then, these things, and that the abolition of slavery, and the reign of negro equality here, may degrade the white man in the same way as it has done in those countries, there is no non-slaveholder with the spirit of the white race in his bosom, who would not spurn with contempt this scheme of Yankee cunning and malice.

It’s always hard to know whether, and to what extent, essays like DeBow’s and Townsend’s shaped the beliefs and motivations of bot the general public in the South and Confederate soldiers, specifically. They are, in may respects, like highly-politically-partisan cable channels and websites today, in that they (or the ideas they express) form part of the larger rhetorical environment that influences individuals’ views. We can get a better, if imperfect, handle on this today through polling (“Where do you mostly get your news?”), but the exact dynamics of the phenomenon 150 years ago are harder to discern.

Another aspect that bears on this, as well, is that essays like these, or excerpts from them, were picked up and carried in other publications across the South, so they got far more circulation than the actual print run of the original pamphlet would suggest. I came across the Townsend quote, for example, in the Trinity Advocate, published in Palestine in East Texas. Arguments like DeBow’s and Townsend’s went far and wide.

I haven’t worked with large assemblies of contemporary sources, but McPherson addresses the differences in stated motivations between slaveholders and non-slaveholders in Cause & Comrades, and gives a number of examples of non-slaveholders who expressed very much the same ideas Townsend and DeBow both argue, that they saw themselves as defending not an economic institution, but a social order, explicitly based on white supremacy, of which the institution of African slavery was central. “Herrenvolk democracy,” he summarizes (p. 109), “– the equality of all who belonged to the master race — was a powerful motivator for many Confederate soldiers.”

McPherson also touches on something that Chandra Manning is much more explicit about, which is the concept of “liberty,” which was an idea shared widely between slaveholders and non-slaveholders alike. When they spoke of principles like liberty and property rights, there is an implicit belief that those are things that apply to white men (and to a much lesser extent, white women), and to no one else (pp. 29-30):

When Confederate soldiers spoke of liberty, they referred not to a universally applicable ideal, but to a carefully circumscribed possession available to white Southerners. No mere abstraction, liberty had to do with the unobstructed pursuit of material prosperity for white men and their families. As one Virginian put it, liberty consisted of the “good many comforts and privileges” that his family could enjoy without outside interference. While exclusive in terms of race, liberty was inclusive in terms of class. In other words, while liberty applied strictly to whites, it applied to all whites, regardless of present social class or economic condition, because all whites, by virtue of being white, enjoyed the right to individual ambition and aspirations of material betterment through means of their own choosing.

The institution of slavery was so central to daily life across much of the South that it is part of the “home and hearth” that so many Confederate soldiers saw themselves as defending.

So while it’s usually impossible to demonstrate that this Debow essay influenced that Confederate soldier, it seems clear that the ideas they expressed were very much a part of political discourse, and found a receptive audience in the Confederate ranks, both among slaveholders and non-slaveholders. Certainly this line of thinking wasn’t the only one out there — individuals’ motivations to do anything are rarely so simple as that — but scholarship like McPherson’s and Manning’s shows that these arguments were absolutely part of the mix, and the common rationalization that non-slaveholders must, Q.E.D., not have seen any interest in defending the institution is just that — a self-serving rationalization that papers over the cognitive dissonance that inevitably goes with Confederate hagiography.

_______________

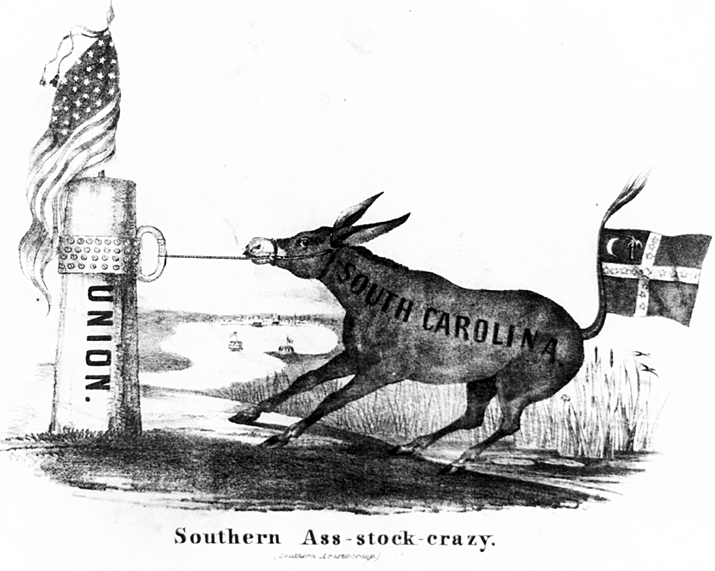

The latter part of this post, beginning, “it’s always hard to know. . ,” was originally a comment in response to Marc Ferguson. In retrospect, it seems more appropriate as part of the text. Image: “Southern Ass-Stock-Crazy (Southern Aristocracy),” 1861, Library of Congress.

Non-Slaveholders’ Stake in Defending the “Peculiar Institution”

Last week we looked at the prevalence of slaveholding in the South in 1860, on the eve of the Civil War. While many in the Southron Heritage™ movement will argue that a tiny, tiny fraction of Confederate soldiers owned slaves — two percent, three percent, five percent — the actual proportion of Confederate households that included slaveholders was several times higher, upwards of a third of all free households across the eleven states that formed the Confederacy. Most folks associated with Confederate heritage groups will, it seems, very quickly volunteer that their own ancestors didn’t own any slaves, and thus the protection and expansion of that institution, so explicitly central to the secession of South Carolina, Mississippi and other states, must not have factored into said ancestors’ decision to fight for the South. It’s an appealing argument, but the reality is not nearly so simple as that.

While the beliefs and motivations of specific individuals are always varied — and, after the passage of 150 years, are very often unknown — on the eve of the war there were many who argued that protection of slavery was explicitly in the interest of all Southern whites, not only those who owned slaves. Newspaper editorials, pamphlets, speeches, all called on the white population of the South, slaveholder and non-slaveholder alike, to stand together in defense of their shared interest in protecting slavery, for themselves, for their families, and for their children.

As Civil War blogger Allen Gathman pointed out recently at Seven Score and Ten, the most influential advocate of this idea was James D. B. DeBow (right). DeBow was a former superintendent of the U.S. Census who, in the years prior to the war, published extensive tracts justifying the institution of slavery as an economic and moral good. There was, perhaps, no stronger or widely-read advocate in the defense of slavery, nor one whose writings — thanks to his service with the Census Bureau — carried the sheen of academic authority that DeBow held. In December 1860, on the eve of secession, the same month South Carolina seceded, DeBow published a booklet titled The Interest in Slavery of the Southern Non-Slaveholder, in which he argued that non-slaveholding whites were every bit as interested in protecting and preserving the institution as the large plantation owners:

As Civil War blogger Allen Gathman pointed out recently at Seven Score and Ten, the most influential advocate of this idea was James D. B. DeBow (right). DeBow was a former superintendent of the U.S. Census who, in the years prior to the war, published extensive tracts justifying the institution of slavery as an economic and moral good. There was, perhaps, no stronger or widely-read advocate in the defense of slavery, nor one whose writings — thanks to his service with the Census Bureau — carried the sheen of academic authority that DeBow held. In December 1860, on the eve of secession, the same month South Carolina seceded, DeBow published a booklet titled The Interest in Slavery of the Southern Non-Slaveholder, in which he argued that non-slaveholding whites were every bit as interested in protecting and preserving the institution as the large plantation owners:

The fact being conceded that there is a very large class of persons in the slaveholding States, who have no direct ownership in slaves; it may be well asked, upon what principle a greater antagonism can be presumed between them and their fellow citizens, than exists among the larger class of non-landholders in the free States and the landed interest there? If a conflict of interest exists in one instance, it does in the other, and if patriotism and public spirit are to be measured upon so low a standard, the social fabric at the North is in far greater danger of dissolution titan it is here.

Though I protest against the false and degrading standard, to which Northern orators and statesmen have reduced the measure of patriotism, which is to be expected from a free and enlightened people, and in the name of the non-slaveholders of the South, fling back the insolent charge that they are only bound to their country by its “loaves and fishes,” and would be found derelict in honor and principle and public virtue in proportion as they are needy in circumstances; I think it but easy to show that the interest of the poorest non-slaveholder among us, is to make common cause with, and die in the last trenches in defence of, the slave property of his more favored neighbor.

The non-slaveholders of the South may be classed as either such as desire and are incapable of purchasing slaves, or such as have the means to purchase and do not because of the absence of the motive, preferring to hire or employ cheaper white labor. A class conscientiously objecting to the ownership of slave property, does not exist at the South, for all such scruples have long since been silenced by the profound and unanswerable arguments to which Yankee controversy has driven our statesmen, popular orators and clergy. Upon the sure testimony of God’s Holy Book, and upon the principles of universal polity, they have defended and justified the institution. The exceptions which embrace recent importations into Virginia, and into some of the Southern cities from the free States of the North, and some of the crazy, socialistic Germans in Texas, are too unimportant to affect the truth of the proposition.

Gotta love that last line about “the crazy, socialistic Germans in Texas.”

DeBow provides a whole range of arguments and carefully-picked data to buttress his position, and goes on to detail ten separate arguments illustrating why the protection of slavery is as much or more in the interest of the non-slaveholder as it is in the man with large numbers of bondsmen. Debow lays out, point by point, explanation of how the continued existence of African slavery protects each white man’s status as an individual, the welfare of his family, the future wealth of his children, and the prosperity of his state and region:

4. The non-slaveholder of the South preserves the status of the white man, and is not regarded as an inferior or a dependant. He is not told that the Declaration of Independence, when it says that all men are born free and equal, refers to the negro equally with himself. It is not proposed to him that the free negro’s vote shall weigh equally with bis own at the ballot-box, and that the little children of both colors shall be mixed in the classes and benches of the school-house, and embrace each other filially in its outside sports. It never occurs to him, that a white man could be degraded enough to boast in a public assembly, as was recently done in New York, of having actually slept with a negro. And his patriotic ire would crush with a blow the free negro who would dare, in his presence, as is done in the free States, to characterize the father of the country as a “scoundrel.” No white man at the South serves another as a body servant, to clean his boots, wait on his table, and perform the menial services of his household. His blood revolts against this, and his necessities never drive him to it. He is a companion and an equal. When in the employ of the slaveholder, or in intercourse with him, he enters his hall, and has a seat at his table. If a distinction exists, it is only that which education and refinement may give, and this is so courteously exhibited as scarcely to strike attention. The poor white laborer at the North is at the bottom of the social ladder, whilst his brother here has ascended several steps and can look down upon those who are beneath him, at an infinite remove.

5. The non-slaveholder knows that as soon as his savings will admit, he can become a slaveholder, and thus relieve his wife from the necessities of the kitchen and the laundry, and his children from the labors of the field. This, with ordinary frugality, can, in general, be accomplished in a few years, and is a process continually going on. Perhaps twice the number of poor men at the South own a slave to what owned a slave ten years ago. The universal disposition is to purchase. It is the first use lor savings, and the negro purchased is the last possession to be parted with. If a woman, her children become heir-looms and make the nucleus of an estate. It is within my knowledge, that a plantation of fifty or sixty persons has been established, from the descendants of a single female, in the course of the lifetime of the original purchaser.

6. The large slaveholders and proprietors of the South begin life in great part as non-slaveholders. It is the nature of property to change hands. Luxury, liberality, extravagance, depreciated land, low prices, debt, distribution among children, and continually breaking up estates. All over the new States of the Southwest enormous estates are in the hands of men who began life as overseers, or city clerks, traders and merchants. Often the overseer marries the widow. Cheap lands, abundant harvests, high prices give the poor man soon a negro. His ten bales of cotton bring him another, a second crop increases his purchases, and so he goes on opening land and adding labor until in a few years his draft for $20,000 upon his merchant becomes a marketable commodity.

7. But should such fortune not be in reserve for the non-slaveholder, he will understand by honesty and industry it may be realized to his children. More than one generation of poverty in a family is scarcely to be expected at the South, and is against the general experience. – It is more unusual here for poverty or wealth to be preserved through several generations in the same family.

8. The sons of the non-slaveholder are and have always been among the leading and ruling spirits of the South; in industry as well as in politics. Every man’s experience in his own neighborhood will evince this. He has but to task his memory. In this class are the McDuffies, Langdon Cheeves, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clays [sic.], and Rusks, of the past; the Hammonds, Yanceys, Ors, Memmingers, Benjamins, Stephens, Soules, Browns, of Mississippi, Simms, Porters, Magraths, Aikens, Maunsel Whites, and an innumerable host of the present, and what is to be noted, these men have not been made demagogues for that reason, as in other quarters, but are among the most conservative among us. Nowhere else in the world have intelligence and virtue disconnected from ancestral estate, the same opportunities for advancement and nowhere else is their triumph more speedy and signal.

9. Without the institution of slavery the great staple products of the South would cease to be grown, and the immense annual results which are distributed among every class of the community and which give life to every branch of industry, would cease. The world furnishes no instances of these products being grown upon a large scale by free labor. The English now acknowledged [sic.] their failure in the East Indies. Brazil, whose slave population nearly equals our own, is the only South American State which has prospered. Cuba, by her slave labor, showers wealth upon old Spain, whilst the British West India Colonies have now ceased to be a source of revenue, and from opulence have been, by emancipation, reduced to beggary. St. Domingo shared the same fate, and the poor whites have been massacred equally with the rich.

One suspects that these arguments convinced a great many white Southerners that, while they might not own slaves now, its was essential to preserve the very fabric of their family and society to protect and defend the “peculiar institution.”

Are you convinced?

_____________

“Ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave.”

It would be a shame to let April slip by without a mention of Texas State Senate Resolution No. 526, which designates this month as Texas Confederate History and Heritage Month. The resolution uses a lot of boilerplate language (including an obligatory mention of “politically correct revisionists”), and also makes the assertion that “ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave.” This is a common argument among Confederate apologists, part of a larger effort to minimize or eliminate the institution of slavery as a factor in secession and the coming of the war, and thus make it possible to maintain the notion that Southern soldiers, like the Confederacy itself, were driven by the purest and noblest values to defend home and hearth. Slavery played no role it the coming of the war, they say; how could it, when less than two percent (four percent, five percent) actually owned slaves? In fact, they’d say, their ancestors had nothing at all to do with slavery.

But it’s wrong.

It’s true that in an extremely narrow sense, only a very small proportion of Confederate soldiers owned slaves in their own right. That, of course, is to be expected; soldiering is a young man’s game, and most young men, then and now, have little in the way of personal wealth. As a crude analogy, how many PFCs and corporals in Iraq and Afghanistan today own their own homes? Not many.

But even if it is narrowly true, it’s a deeply misleading statistic, cited religiously to distract from the much more relevant number, the proportion of soldiers who came from slaveholding households. The majority of the young men who marched off to war in the spring of 1861 were fully vested in the “peculiar institution.” Joseph T. Glatthaar, in his magnificent study of the force that eventually became the Army of Northern Virginia, lays out the evidence.

Even more revealing was their attachment to slavery. Among the enlistees in 1861, slightly more than one in ten owned slaves personally. This compared favorably to the Confederacy as a whole, in which one in every twenty white persons owned slaves. Yet more than one in every four volunteers that first year lived with parents who were slaveholders. Combining those soldiers who owned slaves with those soldiers who lived with slaveholding family members, the proportion rose to 36 percent. That contrasted starkly with the 24.9 percent, or one in every four households, that owned slaves in the South, based on the 1860 census. Thus, volunteers in 1861 were 42 percent more likely to own slaves themselves or to live with family members who owned slaves than the general population.

The attachment to slavery, though, was even more powerful. One in every ten volunteers in 1861 did not own slaves themselves but lived in households headed by non family members who did. This figure, combined with the 36 percent who owned or whose family members owned slaves, indicated that almost one of every two 1861 recruits lived with slaveholders. Nor did the direct exposure stop there. Untold numbers of enlistees rented land from, sold crops to, or worked for slaveholders. In the final tabulation, the vast majority of the volunteers of 1861 had a direct connection to slavery. For slaveholder and nonslaveholder alike, slavery lay at the heart of the Confederate nation. The fact that their paper notes frequently depicted scenes of slaves demonstrated the institution’s central role and symbolic value to the Confederacy.

More than half the officers in 1861 owned slaves, and none of them lived with family members who were slaveholders. Their substantial median combined wealth ($5,600) and average combined wealth ($8,979) mirrored that high proportion of slave ownership. By comparison, only one in twelve enlisted men owned slaves, but when those who lived with family slave owners were included, the ratio exceeded one in three. That was 40 percent above the tally for all households in the Old South. With the inclusion of those who resided in nonfamily slaveholding households, the direct exposure to bondage among enlisted personnel was four of every nine. Enlisted men owned less wealth, with combined levels of $1,125 for the median and $7,079 for the average, but those numbers indicated a fairly comfortable standard of living. Proportionately, far more officers were likely to be professionals in civil life, and their age difference, about four years older than enlisted men, reflected their greater accumulated wealth.

The prevalence of slaveholding was so pervasive among Southerners who heeded the call to arms in 1861 that it became something of a joke; Glatthaar tells of an Irish-born private in a Georgia regiment who quipped to his messmates that “he bought a negro, he says, to have something to fight for.”

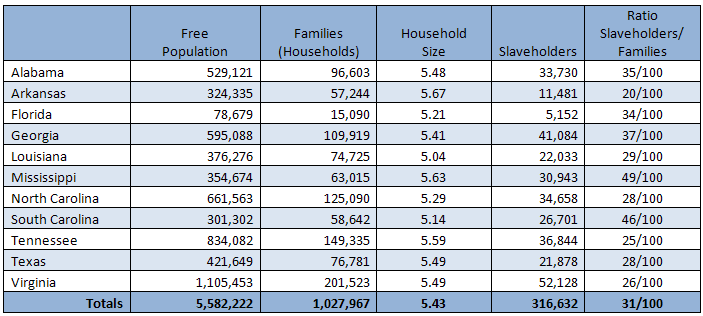

While Joe Glatthaar undoubtedly had a small regiment of graduate assistants to help with cross-indexing Confederate muster rolls and the 1860 U.S. Census, there are some basic tools now available online that will allow anyone to at least get a general sense of the validity of his numbers. The Historical Census Browser from the University of Virginia Library allows users to compile, sort and visualize data from U.S. Censuses from 1790 to 1960. For Glatthaar’s purposes and ours, the 1860 census, taken a few months before the outbreak of the war, is crucial. It records basic data about the free population, including names, sex, approximate age, occupation and value of real and personal property of each person in a household. A second, separate schedule records the name of each slaveholder and lists the slave he or she owns. Each slave is listed by sex and age; names were not recorded. The data in the UofV online system can be broken down either by state or counties within a state, and make it possible to compare one data element (e.g., households) with another (slaveholders) and calculate the proportions between them.

In the vast majority of cases, each household (termed a “family” in the 1860 document, even when the group consisted of unrelated people living in the same residence) that owned slaves had only one slaveholder listed, the head of the household. It is thus possible to compare the number of slaveholders in a given state to the numbers of families/households, and get a rough estimation of the proportion of free households that owned at least one slave. The numbers varies considerably, ranging from (roughly) 1 in 5 in Arkansas to nearly 1 in 2 in Mississippi and South Carolina. In the eleven states that formed the Confederacy, there were in aggregate just over 1 million free households, which between them represented 316,632 slaveholders—meaning that somewhere between one-quarter and one-third of households in the Confederate States counted among its assets at least one human being.

The UofV system also makes it possible to generate maps that show graphically the proportion of slaveholding households in a given county. This is particularly useful in revealing political divisions or disputes within a state, although it takes some practice with the online query system to generate maps properly. Here are county maps for all eleven Confederate states, with the estimated proportion of slaveholding families indicated in green — a darker color indicates a higher density: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, All States.

Observers will note that the incidence of slaveholding was highest in agricultural lowlands, where rivers provided both transportation for bulk commodities and periodic floods that replenished the soil, and lowest in mountainous regions like Appalachia. The map of Virginia, in particular, goes a long way to explaining the breakup of that state during the war.

Obviously this calculation is not perfect. There are a couple of burbles in the data where populations are very low, for example Mississippi, where the census recorded two very sparsely-populated counties having more slaveholders than families (possible, but unlikely), or on the Texas frontier, where the data maps the finding that almost every family probably included a slaveholder. But in spite of its imperfections, it nonetheless presents a picture that more accurately describes the presence of slaveholding in the everyday lives – indeed, under the same roof – of citizens of the Confederate States than the much smaller number of slave owners does.

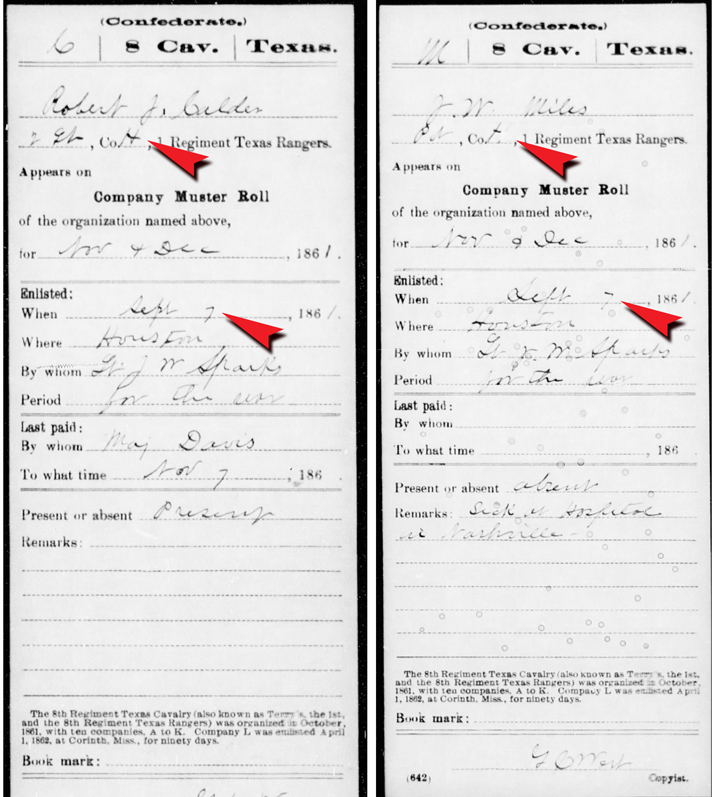

Aaron Perry, whose seven slaves are enumerated above in an excerpt from the 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedule, illustrates the point. Perry, a Texas State Representative who raised hogs and corn in Limestone County (east of present-day Waco) had two sons, William and Mark (or Marcus), living with him at the farm at the time of the census. The elder Perry owned $3,000 worth of land, and nearly four times that in personal property, most of which must have been represented in those seven slaves. When the war came, both sons joined the Eighth Texas Cavalry, the famed Terry’s Rangers. Because neither of the sons – aged 21 and 17 respectively at the time of the census – held formal, legal title to a bondsman, Confederate apologists would claim that they are among the “ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers [that] never owned a slave,” and, by implication, therefore had no interest or motivation to protect the “peculiar institution.” Nonetheless, it was slave labor that made their father’s farm (and their inheritance) a going concern. It was slave labor that, in one way or another, provided the food they ate, the shelter over their heads, the money in their pockets, the clothes they wore, and formed the basis of wealth they would inherit someday. And when they went to war, it was slave labor that made it possible for them to bring with them the mounts and sidearms that Texas cavalrymen were expected to provide for themselves. While the Perry boys left no record of their personal thoughts or motivations upon enlisting, the notion that these two young men must have had no interest, no personal stake, in the preservation of slavery as an institution is simply asinine on its face.

You don’t have to talk to a Confederate apologist long before you’ll be told that only a tiny fraction of butternuts owned slaves. (This is usually followed immediately by an assertion that the speaker’s own Confederate ancestors never owned slaves, either.) The number ascribed to Confederate soldiers as a whole varies—two percent, five percent—but the message is always the same, that those men 150 years had nothing to do with the peculiar institution, they had no stake in it, and that it certainly played no role whatever in their personal motivations or in the Confederacy’s goals in the war. But such a blanket disassociation between Confederate soldiers and the “peculiar institution” is simply not true in any meaningful way. Slave labor was as much a part of life in the antebellum South as heat in the summer and hog-killing time in the late fall. Southerners who didn’t own slaves could not but avoid coming in regular, frequent contact with the institution. They hired out others’ slaves for temporary work. They did business with slaveholders, bought from or sold to them. They utilized the products of others’ slaves’ labor. They traveled roads and lived behind levees built by slaves. Southerners across the Confederacy, from Texas to Florida to Virginia, civilian and soldier alike, were awash in the institution of slavery. They were up to their necks in it. They swam in it, and no amount of willful denial can change that.

Coming up: Did non-slaveholding Southerners have a stake in fighting to defend the “peculiar institution?”

_____________________

Images: Top, list of seven slaves belonging to Texas State Representative Aaron Perry of Limestone County, Texas, from the 1860 U.S. Census slave schedules, via Ancestry. Below, central image on the face of a Confederate States of America $100 note,issued at Richmond in 1862, featuring African Americans working in the field, via The Daily Omnivore Blog.

This post is adapted from one originally appearing in The Atlantic online in August 2010.

Not Surprising

Over at Civil War Emancipation, Donald R. Shaffer highlights a table by David C. Hanson of Virginia Western Community College, that compares slaveholding states’ date of secession with their populations of slaves and slaveholders as recorded in the 1860 U.S. Census. Shaffer notes that “David C. Hanson makes a definite connection between the concentration of slaves and slaveholders in a particular southern states and when it seceded from the Union in 1860-61, and whether it seceded at all. Certainly, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence connecting slavery and Civil War causation, but this table also makes a compelling statistical case.”

No shit. It turns out that for the eleven states that actually seceded, the proportion of free persons owning slaves was an excellent predictor of the order in which they seceded, beginning with South Carolina. I plugged the numbers into Excel and found that the percentage of slaves as part of the state’s overall population was equally reliable as a predictor. Assigning each state a number corresponding to its order of secession (South Carolina = 1, Mississippi = 2, etc.), the correlation coefficient for both the percentage of slaveholders among the free population, and for the proportion of slave among the overall population, was in both cases beyond -0.9. In short, each percentage is a nearly perfect predictor of where each state falls in the order of secession. The states with the largest proportions of slaves and slave-holders seceded earliest.

_____________

Rosewood Cemetery Marker Dedication, Galveston

Update: A new reader asks about the title Dead Confederates juxtaposed with a story about an African American cemetery. It’s the name of the blog, which generally deals with the American Civil War, and I didn’t even realize how it would look. I hope folks will understand and not be offended, because that was not my intent. I apologize for how this looks, and hope readers will consider the blog as a whole, and not by this particular whiplash-inducing combination of phrases.

Tucked away in a nearly-impossible-to-find part of Galveston is Rosewood Cemetery, a burial ground for African Americans between 1911 and the last known interment, in 1944. Historical records identify 411 burials there, but only a handful of graves remain clearly marked. The site was originally a couple of hundred yards from the Gulf beach, but after the Seawall was extended past the site in the 1950s, and subsequent fill operations closed off the cemetery’s natural drainage, leaving the site subject to periodic flooding. Over time, grave markers succumbed to natural deterioration, vandalism or simply settled into the soil. Many of the markers that remain have been displaced from their original locations.

There’s only one marker clearly identifying the person interred there as a former member of the military, that of World War I veteran Ben L. Scott (c. 1896 — Feb. 21, 1937). Many more burials there are of freedmen and -women who were born into slavery. William Lewis (c. 1840 — November 22, 1913) is almost certainly one of those.

There’s only one marker clearly identifying the person interred there as a former member of the military, that of World War I veteran Ben L. Scott (c. 1896 — Feb. 21, 1937). Many more burials there are of freedmen and -women who were born into slavery. William Lewis (c. 1840 — November 22, 1913) is almost certainly one of those.

Eventually the land including the cemetery passed into the hands of local developers John and Judy Saracco. The Saraccos, well-known members of the local community, were aware that the cemetery lay within the boundaries of their new holdings, and had the property surveyed to define its limits. The Saraccos then had the cemetery fenced to maintain its boundary while development went on around it.

In 2006, the Saraccos donated the Rosewood Cemetery land to the Galveston Historical Foundation, which now maintains the property. The formal re-dedication of the cemetery was held in June 2007. In January 2008, local Boy Scout Sean Moran raised money and organized a crew to construct a new rail fence to surround the cemetery property. That fence was destroyed nine months later, during Hurricane Ike, so Moran — by now a college student — raised yet more money and organized volunteers to re-install a new fence again in March 2010.

This coming Saturday, April 16 at 10 a.m., there will be a dedication ceremony for the new Texas Historical Commission Historic Cemetery marker for Rosewood Cemetery, on 63rd Street, just back from Seawall Boulevard. The Galveston Historical Foundation is still seeking information on persons interred at Rosewood; if you have any information on such persons, please contact Brian Davis at 409.765.3419 or brian.davis@galvestonhistory.org.

Two photos of the cemetery in 1999:

And pictures from last Saturday’s cleanup project after the jump:

A Beating in Fort Bend County, Cont.

Over the weekend I posted about the attack on Captain William H. Rock (left), the Freedman’s Bureau agent in Fort Bend County, Texas. Rock was a former USCT officer who joined the Freedmen’s Bureau in mid-1866, and spent two full years, December 1866 to December 1868, as the agent in Fort Bend County, one of the longest tenures in such a position in Texas. Christopher Bean’s 2008 doctoral dissertation, “A Stranger Amongst Strangers: An Analysis of the Freedmen’s Bureau Subassistant Commissioners in Texas, 1865-1868,” gives considerable insight on Rock’s service at Richmond, drawn from that officer’s correspondence with his superiors at the bureau. Rock comes across as a diligent and proactive agent, spending more time visiting the laborers on the farms and plantations of Fort Bend County than he did in his office, and working to adjust freedmen and -women to make the successful transition to cultural and political norms that, in times of slavery, had always been outside their reach.

Over the weekend I posted about the attack on Captain William H. Rock (left), the Freedman’s Bureau agent in Fort Bend County, Texas. Rock was a former USCT officer who joined the Freedmen’s Bureau in mid-1866, and spent two full years, December 1866 to December 1868, as the agent in Fort Bend County, one of the longest tenures in such a position in Texas. Christopher Bean’s 2008 doctoral dissertation, “A Stranger Amongst Strangers: An Analysis of the Freedmen’s Bureau Subassistant Commissioners in Texas, 1865-1868,” gives considerable insight on Rock’s service at Richmond, drawn from that officer’s correspondence with his superiors at the bureau. Rock comes across as a diligent and proactive agent, spending more time visiting the laborers on the farms and plantations of Fort Bend County than he did in his office, and working to adjust freedmen and -women to make the successful transition to cultural and political norms that, in times of slavery, had always been outside their reach.

It was a challenge, to be sure. As noted previously, at the time of the 1860 U.S. Census, there were almost exactly twice as many slaves in Fort Bend County as free persons, with only nine free colored persons in the entire county. By 1870, more than three-quarters of the county’s population was described as “colored.” Fort Bend had been a hotbed of Confederate sympathy; when (white, male) Texans went to the polls to vote on secession in early 1861, the vote in Fort Bend County was 486 to 0. The county sheriff, J. W. Miles, had reportedly been a private in the famously-rowdy Eighth Texas Cavalry, Terry’s Rangers, before being discharged for illness in 1862. Fort Bend County was a rough place, even for a man as seemingly diligent and earnest as William Rock.

For his part, Captain Rock went about his business mostly on his own. Unlike other agents of the bureau in Texas, Rock declined to be provided with a detachment of soldiers to assist in enforcing his authority — at least during the first months of his time in Richmond. It was subsequently reported that he had, in fact, requested a detachment later on, but it’s not clear if such was ever actually provided.

Following my last post, blogger Daniel R. Weinfeld left a detailed comment, remarking on the striking similarities between the official explanation of the attack on Captain Rock, and those that followed the murder of John Quincy Dickinson (right, 1836-71), the Jackson County, Florida Clerk of Court, in 1871. Dickinson, a former officer of the 7th Vermont Infantry and a former agent for the Freedman’s Bureau, was the senior Republican in the county, and a target for white Regulators looking to return the county to white, Democratic control during what became known as the “Jackson County War.” (More about Dickinson’s assassination here.) Weinfeld sees a remarkable parallel in the way both the Dickinson murder, and the assault on Captain Rock two years previously, were explained away by the local white community:

Following my last post, blogger Daniel R. Weinfeld left a detailed comment, remarking on the striking similarities between the official explanation of the attack on Captain Rock, and those that followed the murder of John Quincy Dickinson (right, 1836-71), the Jackson County, Florida Clerk of Court, in 1871. Dickinson, a former officer of the 7th Vermont Infantry and a former agent for the Freedman’s Bureau, was the senior Republican in the county, and a target for white Regulators looking to return the county to white, Democratic control during what became known as the “Jackson County War.” (More about Dickinson’s assassination here.) Weinfeld sees a remarkable parallel in the way both the Dickinson murder, and the assault on Captain Rock two years previously, were explained away by the local white community:

The “scenario” presented in Flake’s Bulletin conforms exactly with the same rationalizations/accusations made by Regulators at other times and places to justify assaults on Bureau officers and Republican officials in the South. . . . In the “investigation” [of Dickinson’s murder] conducted by the county judge, as reported by FL Democratic newspapers, allegations were made that (1) the assassin was a black man, who (2) was jealous over an alleged affair between Dickinson and a black woman and (3) that Dickinson had swindled local land owners out of their property at tax auctions. Otherwise, the papers asserted, Dickinson had been respected by his white neighbors! All this slander was vigorously denied by Dickinson’s friends and the Republican press. My research shows that Dickinson was without a doubt assassinated by Regulators waiting in ambush. The black man involved was likely hired by the Regulators as a lookout. Dickinson’s “offense” was his political activity as a Republican and his defense of voting and civil rights for African Americans.

It’s almost like the Regulators had a check list they passed around: implicate African American in committing the assault – check; accuse victim of sexually consorting with blacks – check; then allege financial improprieties by victim – check. . . . I’m also guessing that examination of the Democratic press over the previous two years would show that Capt. Rock was not so completely loved by local whites as Flake’s pretends, and that local whites had made insinuations about his conduct or partiality to blacks in the past.

There actually are plenty of hints as to some of what was going on in Richmond with Captain Rock, and the notion that (as was claimed after the attack) Rock “was regarded with favor by nearly all the citizens” was patently untrue. As before, here are some contemporary news excerpts. We can all read the words, of course, but what do you read behind them?

Flake’s Bulletin, June 15, 1867:

We are informed by Lieutenant Rock, agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau of Fort Bend county, that the people of that county exhibited sentiments of perfect submission to the reconstruction laws, and a desire to abstain entirely from all participation in political matters, except that of voting for such union men as may be nominated. It would be well for them to give this sentiment public expression.

Galveston Daily News, September 5, 1867. Sheriff Miles, it seems, had physically attacked Captain Rock more than a year before the New Years’ Eve incident:

SHERIFF VERSUS CAPTAIN.

The Brazos Signal says Sheriff J. W. Miles, of Fort Bend, complained to Capt. Rock, Bureau Agent at Richmond, of unwarrantable interference with his duties. The Captain threatened the Sheriff with removal, and the latter replied that a whipping would follow. The removal order came, and the Signal tells the rest:

Mr. Miles has always been very prompt in the discharge of his duties, and suddenly remembering that he had promised the captain, hurried off in search of him., finding him near the Verandah Hotel. We only know the result of the meeting, viz: that Mr. Miles kicked and cuffed the captain in a manner unbearable, and the captain would not have been to blame in the least for resenting it on the spot. The affair was strictly personal, and we think the captain has too much generosity to involve the whole community in the difficulty.

Mr. Miles was arrested by the City Marshal, and gave bond for his appearance Friday morning, but not giving the captain due credit for generosity, he forfeited the bond by not appearing. The Captain will not certainly be harsh with Mr. M., as he showed no malignant intent. Fighting is supposed to be one of the principal ingredients of a soldier’s profession, and we think it is characteristic of any profession whatever, to look kindly on an amateur of marked ability. We hoot at the idea of the captain wanting Gen. Griffin, and the principal part of the army, to support him against an amateur, though he has shown himself unusually proficient. It is to be regretted, but we might as well laugh as cry. Captain Rock was tried before his Honor the Mayor and dismissed.

What do you make of the last paragraph, going on at length about Capt. Rock’s supposed fighting ability, “one of the principal ingredients of a soldier’s profession?” What’s the Brazos Signal saying?

Galveston Daily News, September 5, 1867

Fort Bend. – The Brazos Signal of the 31st ult., says:

A citizen wants to know what construction the registrars can place on the act of Congress, to register a negro [sic.] who has been tried and convicted of a felony, when they will not allow a man to register merely because he once superintended hands at work on the road. This, the gentleman informs us, is the case. That Capt. Rock asked the negro if he had ever been up before a court, and he told him all about it. Such work puzzles men that think they are loyal, they can’t see by “those lamps.”

Here is the total registration, up to Aug. 30th, of Fort Bend County, furnished us by Capt. Rock, fewer whites and more black votes than any other county in the state – 110 whites to 1198 blacks; total 1218; rejected only 28. We can’t register without crying; the office will close on the 6th. It is our duty to try.

An 1867 Harpers Weekly cartoon by Thomas Nast, ridiculing both freedmen voting for the first time, and resentful, disenfranchised former Confederates.

Flake’s Bulletin, February 8, 1868, warning against planters being “fleeced” by the Freedmen’s Bureau.

In speaking of the aid offered by the Freedmen’s Bureau, the Galveston News says:

It is true that the planters are hardly pressed, and it is true that the bureau makes the offer of help without requiring interest. Yet the precaution taken for securing the principle and other things connected with it, should be looked into carefully before the offer is accepted. We frankly confess that some scheme for fleecing and oppressing the planters will be gotten up, in the hope that their great and pressing necessities will induce them to embrace it. And therefore we join the New Orleans Bulletin in advising the planters to examine every proffer of aid through the bureau with critical inspection before imposing responsibilities on themselves by its acceptance.

A man, named Wm. Shakespeare, once said something about “conscience making cowards of people.” Can the News remember the quotation?

And finally, from Flake’s Bulletin, January 20, 1869, giving a somewhat different account of the incident from the assailant, Tom Sherrard/Ross:

THE RICHMOND AFFAIR.

In the News of yesterday appears a card of R. J. Calder, Esq., County Judge of Fort Bend, half a column in length, in reply to a card of Capt. Rock, published in this paper. A gentleman requested us to copy the card of Judge Calder, which we are compelled to decline to do for the following reasons: First. Had Judge Calder desired its publication in Flake’s Bulletin, he would have addressed it himself to the bulletin, not to the News. Second. The card of Judge Calder is too lengthy. We have already published both sides of the affair, to wit: the card of Capt. Rock and the card of many citizens of Richmond, published in the 13th inst. But we append the affidavit of the negro [sic.], Tom Ross, the man who attacked and beat Capt. Rock, embraced in the card of Judge Calder:

STATEMENT OF TOM ROSS.

On the first night of January, 1869, there was a negro dance at Capt. Rock’s quarters in Richmond. I went to the dance, hearing that it was a free ball for the blacks. I remained there for a quarter of an hour, and then left. Returning a short time afterwards, I met Frances Lamar, a colored girl, who was kept by Capt. Rock as his wife. She was standing at the door; on seeing me she left and went to the Captain’s bed-room. Soon afterwards she and the Captain came out of the room; the Captain had a double-barreled shot gun behind him. The Captain approached me, and turning half-way round, said to me, “Take this,” meaning the gun. I stepped back from him, and told him, “I did not want it.” The Captain walked away and to some persons, and immediately approached me again. His woman asked him if he had heard what I said. On answering “no,” she told him that I said I did not want the gun. The woman had taken the gun from the Captain, and had it in her hand at this time. The Captain then said to me, “Do you see that door?” I answered “yes.” He said, “Then you take it, and that God d__n quick.” The fight then commenced by my striking him with my naked fist, having no weapon of any kind with me. While fighting, this woman attempted to shoot me with the gun, but was prevent by bystanders. The Captain getting the worst of it, I was taken off him, and I straightway left the house. No person had offered me money to whip the Captain, neither did I go there expecting a difficulty.

I was arrested and tried before a magistrate, Judge R. J. Calder, and fined $10 for fighting. I was born the slave of Judge John Brahsear, of Houston.

His

Tom X Ross

MarkThe State of Texas, Fort Bend County. —–

Personally came and appeared before the undersigned authority, Tom Ross, a freedman, who, being by me duly sworn, says that the forgoing affidavit, signed by him making his mark, and all the statements and allegations therein contained, are true.

In testimony whereof I hereunto sign my name and affix my seal of office, this, 13th day of January, 1869.

R. J. Calder,

County Judge, Ft. Bend Co.

Here’s a fact that this news item omits: Judge Calder’s son, also named Robert James Calder, had enlisted on the same day, in the same company (Co. H), of the Eighth Texas Cavalry as Sheriff Miles (below). The two young men served together for a year before Miles’ discharge. The younger Calder was later made an officer, and was killed in action in January 1864. Does this fact have any relevance?

_____________

A Beating in Fort Bend County

The other day a commenter dismissed my argument about the importance of interpreting the historical evidence, and making a critical assessment of each bit of documentation that bears on a particular subject. Practicing history, I had said, requires making careful judgments about the sources at hand. “I make no judgments on [sic.] way or the other. . . ,” my correspondent assured me, “I just present the historical fact.”

I thought about that little bit of self-deception this weekend when I came across two accounts of the beating of Captain William H. Rock (right), the Freedman’s Bureau Agent at Richmond, Texas, late on New Years’ Eve, 1868. Captain Rock was appointed to the bureau in June 1866, and in January 1867 was assigned to the office in Fort Bend County, west of Houston. Fort Bend lay at the heart of Anglo Texas, being part of Stephen F. Austin’s original colony, and was later home to several of the state’s largest plantations. At the time of the 1860 U.S. Census, slaves outnumbered free persons in Fort Bend County, two-to-one. By 1870, the ratio of “colored” persons to all others in Fort Bend was more than three-to-one.

I thought about that little bit of self-deception this weekend when I came across two accounts of the beating of Captain William H. Rock (right), the Freedman’s Bureau Agent at Richmond, Texas, late on New Years’ Eve, 1868. Captain Rock was appointed to the bureau in June 1866, and in January 1867 was assigned to the office in Fort Bend County, west of Houston. Fort Bend lay at the heart of Anglo Texas, being part of Stephen F. Austin’s original colony, and was later home to several of the state’s largest plantations. At the time of the 1860 U.S. Census, slaves outnumbered free persons in Fort Bend County, two-to-one. By 1870, the ratio of “colored” persons to all others in Fort Bend was more than three-to-one.

One of the particular difficulties in writing about the Texas and the South in the immediate postwar period is that much of the press at the time was highly partisan, with individual newspapers closely aligned with specific political parties and candidates. During Reconstruction, Texas papers were particularly divided over the threat, and even the actual existence, of the “Ku Kluxes.” Some, like the Houston Union and the Austin Republican, spoke out early and vehemently against the group, while others insisted they were a myth, and argued that the violence and intimidation attributed to them were actually the work of Radical Republican groups like the Loyal League.

So here’s your chance to wade into two very different accounts of the same incident, published in different newspapers. How would you assess these two accounts? What might make you question the reliability of one or the other, and why? What makes your Spidey Sense tingle? What questions do you have after reading these, and how would you address them?

From the Houston Union, January 8, 1869

OUTRAGE AT RICHMOND, TEXAS

The Ku Klux Rampant! They assault and attempt to assassinate Capt. Rock, Agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau. – They leave him for dead.

From Capt. W. H. Rock, who has been living at Richmond, Fort Bend County, and acting as agent for the Freedmen’s Bureau for that county, we learn the following particulars of a most cowardly and brutal assault upon him upon the night of the 1st of January. The Capt. was first attracted by a noise about his premises, and glancing out of the window of his private room discovered a number of white men about his house. He immediately went from his private room to his office adjoining. On opening the door he was knocked down by an unprincipled negro [sic.] named Tom Sherrard, who he afterwards learned had been employed by the Ku Klux to do the deed. After knocking the Capt. down, a couple of the Klan filed into the room, and standing between a colored man who had come to the Capt.’s rescue and the prostrate Capt., permitted the black ruffian to kick and beat him until it was supposed life was extinct. The names of the white men so far as known to Capt. Rock, who participated in this brutal assault upon a representative of the United States Government, are James McGarvey, Joe Johnson, and the Sheriff of the county, one J. W. Miles. The two former, with drawn six shooters, prevented aid from Capt. Rock’s friends, while the latter was heard to remark as they left the house, “it was well done,” supposing, of course, that Capt. Rock was dead. Life, however, was not extinct, and after departure of the murderous crew, his friends succeeded in caring for, and restoring him. Knowing that if it was found out he was alive, they would return, Capt. Rock secreted himself in a neighboring hen-coop, where he remained until next morning, when he made complaint to the chief justice of the county, but perceiving the signs about him and the information brought to him by trusty colored men, that his life would pay the forfeit of an appearance against the parties, Capt. R. concluded to leave the place. Accordingly, Saturday night he secreted himself in the cabin of a friendly colored man, where he remained until Sunday night. In the meantime, the country round about was scoured, and every negro cabin entered and searched, but in vain. His hiding place was secure. While this secreted, word came to him that Capt. Bass, the County Assessor and Collector had made threats to shoot him on sight. Sunday night the 3d., he started to get across the Brazos. Monday night found him across, but without means to getting to Houston some thirty miles away., as the colored people in the whole neighborhood had been visited and their lived threatened if they gave him any assistance in escaping. Monday and Tuesday thus passed away, and as good luck would have it, a horse was procured and after riding all night the Capt., arrived safely in Houston covered with mud and disfigured and sore by bruises.

We are assured by Capt. Rock that the above statement is a true narrative of this great outrage and that it can all be sustained in a court of justice, or before a military commission. The colored men who all know the facts of the case, would not dare to testify in any court at Richmond without the presence of troops. One of them, expressing sympathy for Capt. Rock, was most cruelly beaten, and subsequently, at night, taken from his cabin and beaten until he was supposed to be dead, after which, tieing [sic.] a rope about his neck, he was dragged to an out of the way corner and left for dead.

Other outrages have been committed recently in this delectable town. Last Sunday a band of young rowdies went to the church where the colored people were holding [a] religious meeting, and literally drove them out, and broke up the meeting.

The teacher of the colored school in Richmond, has been driven away, and violence and treason stalks abroad in all its hideous deformity.

This is a terrible picture, and we shall be denounced for exposing it to the public; but the truth is not half told. In truth, there is not a loyal man in the town of Richmond. As an example, a prominent merchant there, named Greenwood, and the express agent, one Albertson, openly avowed they would spend their money freely to prevent the hired ruffian, Sherrard, from being brought to justice. We call upon the managers of the Express Company in this city to remove this man, who thus, by his means and influence, encourages the commission of outrages upon representatives of the Government.

Capt. Rock has often signified to the commanding General the necessity of stationing troops at Richmond. He has for a long time been cognizant of the disloyal disposition of the people there, and knew that as soon as the Bureau was discontinued the rights of the colored people would be utterly ignored, which he now informs us is the case. They are intimidated, brow beaten and worried, and unless a stop is put to it, a fearful outbreak ere long will be the consequence.

An official report of the state of affairs in Fort Bend county will be made by Capt. Rock to Gen. Canby, and we hope and trust the latter will send sufficient troops there to bring all concerned in this affair to justice, as well as protect the loyal men of the county from the malignant persecutions of the Ku-Klux cut throats.

The town where public sentiment permits such outrages as narrated above, should be put under military government and kept there until its return to good behavior makes it safe to remove it.

A week later, on January 16, 1869, Flake’s Bulletin in Galveston published a rebuttal signed by prominent members of the Richmond community, including two men implicated in the previous article, Sheriff J. W. Miles and Express Agent William H. Albertson:

ATTACK ON THE FREEDMEN’S BUREAU AGENT AT RICHMOND.

Special to Flake’s Bulletin.

Houston, Jan. 7 – Capt. Rock, lately in charge of the Freedmen’s Bureau at Richmond, has just arrived in this city, having ridden from that place last night, in order to escape the pursuit of a band of desperadoes in that county. – He was attacked, badly beaten, and was left for dead. His present appearance is sufficient evidence of the treatment to which he was exposed. The outrage occurred on the night of the 31st ult. and the 1st. inst. The majority of citizens deplore the act, and assisted the Captain to escape.

Flake’s Bulletin, Jan. 8.

We desire to speak in defence of our county, and give a truthful account of the subject in the above extract.

Capt. Wm. H. Rock, Sub-Assistant Commissioner of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, lived in this county for about two and a half years, and during that time was regarded with favor by nearly all the citizens. Several decisions of his bore heavily with some, but they, as well as the public, were charitable enough to attribute the same to the evil machinations of the “ardent,” instead of any ill feeling that the Captain possessed; and towards the close of his administration it was often remarked that he had made about as good an officer of the kind as we probably could have gotten. Many regretted that his office compelled one who seemed so much a gentleman to associate with freedmen to the exclusion of whites.

Well, the Bureau collapsed, and when Captain Rock became free – no longer obedient to his masters – it was expected that he would assert his rights, and fully justify the good opinion that had been formed of him; but his actions on the event proved most conclusively that his just, and even willing disposition to deal fairly with the whites was caused alone from fear, and that the “nigger” was in him from the first, but for that aforesaid fear. Now comes the cause for which this Sabraite was forced to flee the land, as alleged above. During Christmas week Capt. Rock, having no further use for an office, converted his establishment into a ball room, and darkey maidens, accompanied by African beaux, held nightly revels to sweet sounds of music. It was at one of these lovely affairs that Tom Sherrod, a very worthy freedman, attended – not, however, without an invitation from “Captain and Mrs. Rock,” in writing. This last personage, a dark and bony [bonny?] Venus, formerly the property of one of our citizens. Previous to the time, Capt. R. had insulted the wife of Tom, yet he (Tom) went to the ball, was ordered out, and it is reported that Capt. R. drew upon his a double-barreled gun, and that Tom was acting in self-defense.

This may be so or not; certes that Tom demolished the valiant captain in the presence of the whole party. Now we firmly believe that no jury in the United States would have convicted this boy Tom, or any other man, for chastising the brute who insulted his wife, even had the charge been murder instead of simply assault.

Upon the following day Captain R. made an affidavit that Tom had assaulted him with brass knuckles, and a warrant was issued for his arrest; in the mean time a distress warrant was issued, and Capt. Rock’s furniture, etc., was attached for house rent, and he left in charge of same – not being able to vacate on account of the wounds from which he was still suffering. That night, though, the attached articles were conveyed, under cover of darkness, to some unknown place, and the captain ditto, no one knows where, and few except his creditors care. He leaves many debts behind, due to both whites and blacks. The latter he deceived by telling them he was going to Austin after troops, while the former knew he was making tracks from the countless hundreds of dollars which were pressing him.

This is but a meagre account of all the acts of Captain Rock in this place, and we would have preferred his departure from our midst in silence, and would have done so except for the flagrant falsehoods contained in the above extract.

Since writing the above we learn that the freedman Tom was arrested and tried yesterday, and was fined ten dollars and costs.

C. H. Kendall, D. C. Hinkle, J. W. Miles, W. C. Hunter, Geo. O. Schley, E. Ryan, G. W. Pleasants, S. R. Walker, Ed. D. Ryan, W. Andrus, T. J. Smith, G. F’ Cook, J. P. Marshall, H. L. Somerville, R. F. Hill, B. W. Bell, G. M. Cathey, J. T. Holt, Chas. C. Bass, Alex Curr, Wm. Ryon, W. K. Davis, J. H. Hand, N. G. Davis, S. Mayblum, H. Jenkins, W. H. Albertson.

The statement of the foregoing extract is not true.

W. E. Kendall, B. F. Atkins

Why did not Captain Rock pay me his board bill, and settle with the Union League for money of theirs that he used for his own purposes?

W. P. Huff, Member Union League, Fort Bend Co.

______________

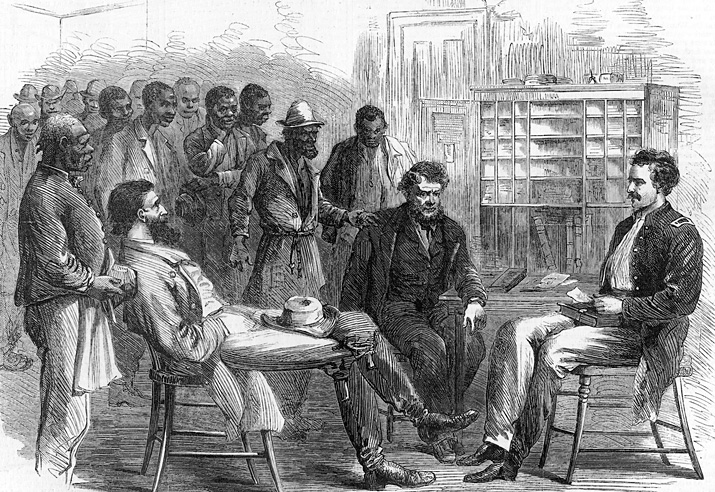

Image: The Freedmen’s Bureau at Memphis, c. 1868. William H. ROck CDV portrait via Cowan’s Auctions.

Brief Updates

Things have been busy of late here, and postings limited. So here are a few quick updates.

If you haven’t heard, Kevin’s blog, Civil War Memory, was selected for digital archiving by the Library of Congress as part of their efforts to document the Civil War Sesquicentennial. How cool is that?

A week ago Friday, long after normal business hours, I e-mailed the Texas State Library in Austin to request a Confederate pension file. The official turnaround time is 4-6 weeks, but this Friday (five business days) I got an e-mail that the copies were already in the mail. Props to the library staff in Austin.

I’ve added two new blogs to the roll at right, Civil War Medicine (and Writing) and Notre Dame and the Civil War. Both are written by Jim Schmidt, a Civil War historian who’s published several very well-received works, including Notre Dame and the Civil War: Marching Onward to Victory, Lincoln’s Labels: America’s Best Known Brands and the Civil War, and the edited volume, Years of Change and Suffering: Modern Perspectives on Civil War Medicine. Welcome to the blogroll, Jim. It’s because of people like Jim that my Amazon purchases ran to thirteen damn pages last year.

Finally, just up the road a ways, a Reconstruction-era Freedman’s settlement has been formally added to the National Register of Historic Places.

______________

Image: Sketch of a “double-ender” Union gunboat by A. R. Waud. Library of Congress.

137 comments