Merry Christmas, Y’all!

_____

Return Forrest to Elmwood Cemetery

This old post from the summer of 2015 seems relevant this morning.

Last week Memphis Mayor A. C. Wharton called for the remains of Nathan Bedford Forrest, his wife, and the monument that stands above them, to be returned to the city’s Elmwood Cemetery. This move is not unexpected, as monument and the park surrounding it — renamed Health Sciences Park in 2013 — have been contentious in the city of Memphis for a long time now.

This call for Forrest’s return to Elmwood comes, of course, in the wake of several states taking action to remove or end official display of Confederate iconography, from flags to specialty license plates to statues. While I think we, as southerners, need to catch our breath and think a little more deliberately when it comes to monuments of long-standing, there is actually a strong and affirmative case — a pro-Forrest case, if you will — when it comes to the site in Memphis. I’ve communicated with several people who have been interested in Forrest for a long time, and know his story well. They point out that he and his wife, Mary Ann Montgomery Forrest, were originally interred at Elmwood, and it was not until the early 20th century, three decades after the general’s death, that their remains were moved to a central park downtown. It’s a case, in many respects, like that of Robert E. Lee at Washington College, now Washington and Lee University, where a later generation decided they knew better than the general himself what he wanted.

At Elmwood, he and Mary Ann would lie again among twelve hundred other Confederate soldiers. (Perhaps it’s not mere coincidence that the statue’s bronze gaze has been fixed on Elmwood all these years.) Besides which, a transfer of Forrest’s remains and re-interment a mile away at Elmwood would give the heritage folks the opportunity for a procession and pageantry the likes of which haven’t been seen since the burial of the H. L. Hunley crew at Charleston in 2004. Lord knows, to so many of Forrest’s fans practicing history consists mainly of dressing up and solemnly parading with Confederate flags. It’s a win for all concerned — for the Forrests, who apparently preferred being at Elmwood; for the city of Memphis that, rightly or wrongly, wants to be done with what used to be known as Forrest Park; and for the heritage crowd that, with a little nudging, can undoubtedly be convinced that a move is actually the right and proper thing to do. A recent Tennessee law would seem to prohibit moving Forrest and the monument, but with everyone on board with it, I’m sure enabling legislation in Nashville is a forgone conclusion.

Confederate graves at Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis. Forrest should be here, too.

The specific circumstances of the Forrest case make that call easy; the case for moving, or removing, other Confederate monuments is more difficult, and requires more deliberation. Speaking for myself, I’m ambivalent about it. While I adamantly support the authority of local governments to make these decisions, I’m not sure that a reflexive decision to remove them is always the best way of addressing the problems we all face together. Monuments are not “history,” as some folks seem to believe, but they are are historic artifacts in their own right, and like a regimental flag or a dress or a letter, they can tell us a great deal about the people who created them, and the efforts they went to to craft and tell a particular story. In 2015 it would be hard to find someone who would unequivocally embrace the message of the “faithful slaves” monument in South Carolina, but it can’t be beat as documentation of the way some white South Carolinians saw the conflict thirty years after its end, and wanted others to, as well. (Maybe York County could put a sign next to it with an arrow saying, “no, they really believed this sh1t!”)

I’ve written before about the Dick Dowling monument in Houston (right). It honors Dowling for his command of Confederate artillerymen at the Battle of Sabine Pass in 1863, but from its dedication in 1905, it was a rallying point for Houston’s Irish community, many of whom came after the war. (It was sponsored, in large part, by the Ancient Order of Hibernians.) Certainly today, as I learned firsthand, the emphasis at the annual ceremony there is much more Irish in character than Confederate. It means a great deal to those folks, many of whose Irish ancestors’ arrival in this country postdates the Civil War by decades. They have no personal connection to the war or to the Confederacy, yet the Dowling monument nonetheless serves as a common bond among them irrespective of the uniform worn by the marble figure at the top. It really would be a shame to lose that.

I’ve written before about the Dick Dowling monument in Houston (right). It honors Dowling for his command of Confederate artillerymen at the Battle of Sabine Pass in 1863, but from its dedication in 1905, it was a rallying point for Houston’s Irish community, many of whom came after the war. (It was sponsored, in large part, by the Ancient Order of Hibernians.) Certainly today, as I learned firsthand, the emphasis at the annual ceremony there is much more Irish in character than Confederate. It means a great deal to those folks, many of whose Irish ancestors’ arrival in this country postdates the Civil War by decades. They have no personal connection to the war or to the Confederacy, yet the Dowling monument nonetheless serves as a common bond among them irrespective of the uniform worn by the marble figure at the top. It really would be a shame to lose that.

I think we need to be done, done, with governmental sanction of the Confederacy, and particularly public-property displays that look suspiciously like pronouncements of Confederate sovereignty. The time for that ended approximately 150 years ago. But wholesale scrubbing of the landscape doesn’t really help, either, if the goal is to have a more honest discussion about race and the history of this country. I’m all for having that discussion, but experience tells me that it probably won’t happen. It’s much easier to score points by railing against easy and inanimate targets.

_________

Forrest monument image via PorterBriggs.com. Elmwood Cemetery image via ElmwoodCemetery.org.

Hawkins Meeting January 4: Supplying the Texian Army

Join the Charles E. Hawkins Squadron of the Texas Navy Association on Thursday evening, January 4, at Fisherman’s Wharf Restaurant in Galveston for a Hawkins Squadron meeting and a presentation by Dr. Carolina Castillo Crimm, “”Supplying the Texian Army: Fernando de León and the New Orleans Connection.”

Dr. Crimm, a native of Mexico, came to the United States when she was 17. She holds degrees from the University of Miami, Texas Tech and completed her Ph.D. in Latin American History at the University of Texas at Austin. Among her many books and articles is the award-winning De León: A Tejano Family History (2004). During her forty years in teaching, she has won numerous awards including the prestigious Piper Award as one of the best teachers in Texas. She has recently retired and been honored as a Professor Emeritus in History from Sam Houston State University for her work with her students, her university and her community. She lives in Huntsville, Texas with her husband, Jack.

Dr. Crimm, a native of Mexico, came to the United States when she was 17. She holds degrees from the University of Miami, Texas Tech and completed her Ph.D. in Latin American History at the University of Texas at Austin. Among her many books and articles is the award-winning De León: A Tejano Family History (2004). During her forty years in teaching, she has won numerous awards including the prestigious Piper Award as one of the best teachers in Texas. She has recently retired and been honored as a Professor Emeritus in History from Sam Houston State University for her work with her students, her university and her community. She lives in Huntsville, Texas with her husband, Jack.

The evening will begin with a meet-and-greet and cash bar at 6:30 p.m. with dinner and Dr. Crimm’s presentation at about 7:30. A limited Fisherman’s Wharf entree menu will be available, and folks will be responsible for purchasing their own food and drinks. Those wanting to attend should RSVP to Andy Hall, (409) seven-seven-one-7433, or by e-mail to maritimetexas-at-gmail-dot-com.

The Texas Navy Association is a private, 501(c)(3) organization, dedicated to preserving and promoting the historical legacy of the naval forces of the Republic of Texas, 1835-46. The mission of the Texas Navy Association is to preserve and promote an appreciation of the historic character and heroic acts of the Texas Navy; to promote travel by visitors to historical sites and areas in which the Texas Navy operated; to conduct, in the broadest sense, a public relations campaign to create a responsible and accurate image of Texas; and to encourage Texas communities, organizations, and individuals, as well as governmental entities, to participate with actions and money, in pursuit of these objectives. Membership in the Texas Navy Association is open to all persons age 16 and over who have an interest in Texas history and want to help support the goals of the organization.

In Galveston, the Charles E. Hawkins Squadron was organized in the fall of 2016, and meets on the first Thursday evening in odd-numbered months at Fisherman’s Wharf Restaurant.

______

“Ex. insufficient”: The Leadership of Midshipman Edward Lea

Some of you will be familiar with the story of Lieutenant Commander Edward Lea, Executive Officer of USS Harriet Lane, who was mortally wounded in the Battle of Galveston on New Year’s Day 1863. Lea was famously reunited with his father Albert, a Confederate staff officer, after the battle. After Major Lea went to obtain an ambulance to have his son transported to a hospital, the naval officer’s shipmates asked what they could do for him. Nothing, he replied, “my father is here.” Those words are now chiseled into Edward Lea’s tombstone (above, in 2011).

Recently I happened on Lea’s disciplinary record from his time at the the U.S. Naval Academy. Lea got himself written up pretty regularly, generally for minor infractions — “talking at battery exercise,” “out of room in study hours,” “absent from parade,” and the like — but one of the more serious incidents happened in January 1854, during his Second Class (junior) year, for “allowing a hissing noise in his crew on leaving the Mess Hall on the 24th and not reporting the same.” In the last column of the entry is the notation, “Ex[cuse] insufficient.” And they threw the book at him — ten demerits.

At the risk of over-interpreting this entry, it sure reads as though one of Lea’s squad members made a vulgar or disrespectful noise directed at someone or something and, when one of his superiors demanded an answer, Lea declined to name the offender or assist in his discovery. And so Edward Lea himself took the demerits, quite likely more than the original offender would’ve received.

If that’s what happened, that’s leadership. There’s no way to know what or who prompted this incident in the first place, but Lea took responsibility for it, and refused to point the finger at the actual culprit. It’s also the kind of move that — no matter what they might say — earns the respect of both his superiors and the lower class midshipmen he led. It suggests a great deal about his character and style of leadership, and explains why, after he died in action nine years later, his comrades saw to his proper and respectful burial.

________

Talkin’ Civil War Stuff

I’m pleased to announce that I will be speaking on Wednesday, December 27, at the Texas City Museum at 409 Sixth Street N, in Texas City. I will be on the program with my friend and colleague Ed Cotham, who will be speaking about the Battle of Galveston. It’s gonna be fun, y’all, so please come out if you can.

“Captain Dave Versus the Yankees”

1 p.m. Wednesday, December 27On a Sunday morning in the spring of 1864, the lives of two men intersected violently on the deck of a blockade-running schooner off the mouth of the Brazos River. In many ways, the two men were very much alike. Both were young and in the prime of their lives. Both were professional merchant seamen, and both were immigrants to this country. But the circumstances of war brought these men, who otherwise might have been fast friends, together in violent conflict.

The story of these two men, Dave McCluskey and Paul Börner, embodies the back-and-forth story of blockade running on the Texas coast during the American Civil War. While Texas was far from the center of the conflict, it remained an important part of the Confederacy and major source of cotton being shipped overseas. Texas’ importance actually grew during the war, as other ports on the Atlantic and Gulf coast were systematically seized by U.S. forces. Texas experienced a flurry of blockade-running activity in the last months of the conflict, with the last runners slipping in and out of Galveston some six weeks after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox and the collapse of Confederate armies in the east.

Andy Hall has volunteered with the office of the State Marine Archaeologist at the Texas Historical Commission since 1990, helping to document historic shipwrecks in Texas waters. From 1997 to 2002, Hall served as Co-Principal Investigator for the Denbigh Project, the most extensive archaeological investigation of a Civil War blockade runner to date in the Gulf of Mexico. Hall writes and speaks frequently on the subjects of Texas’ maritime history and its military conflicts in the 19th century.

“Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston.”

2:30 p.m. Wednesday, December 27At the end of the Civil War, Galveston was the last major Confederate port. But this result came only after a land and sea battle in which Confederate forces recaptured the city from the Union, the only major port that the Confederates ever recaptured. The Battle of Galveston, which took place on January 1, 1863, was the biggest Civil War battle in Texas and one of the most unusual of the entire war. In his multi-media presentation, based on his award-winning book of the same title, Ed Cotham discusses the details of the battle and its important consequences for Texas and the conduct of the war.

A former President of the Houston Civil War Round Table, Ed Cotham (right) has written four award-winning books on the Civil War, including Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, which was published by the University of Texas Press in 1998. This book has been hailed as a “Texas Classic.” Ed has served as a project historian on several Texas shipwreck projects and is active in the movement to interpret and preserve historic sites. He is also a frequent lecturer and battlefield guide. When he is not researching and writing on the Civil War, Ed serves as Director and Chief Investment Officer for the Terry Foundation, the largest private provider of college scholarships in Texas. http://www.edcotham.com/

_______

Private Stevens’ Discharge

In a feature article I wrote a while back for the Civil War Monitor magazine, I mentioned the story of Private Z.T. Winfree, a Confederate soldier who was stationed here in Galveston at the time of the final Confederate collapse in the spring of 1865. On May 24, he and his comrades witnessed a crowd of soldiers and civilians who swarmed aboard blockade runner Lark and looted the vessel for anything and everything they could carry away:

That same evening, Winfree and his messmates were transported by train to Houston as part of a general military evacuation of Galveston Island. The following day in Houston, Winfree witnessed similar scenes of looting, “a general pillage of all things which the Confederacy had for her soldiers, such as ordnance, commissary and quartermasters’ supplies, C.S. mules, wagons, etc.” Winfree saw a crowd of soldiers at one of the buildings used as a headquarters, and learned that discharges were being freely handed out to all who requested them. The clerks soon ran out of printed discharge forms, so many soldiers, including Winfree, received papers granting them open-ended furloughs from their units. “We had not been acting very honorably for the past two days,” Winfree reflected years later, “but after all we had only been taking our own.”

Winfree painted a vivid picture of the chaos and confusion at Confederate headquarters in Houston, where harried clerks scrambled to fill out discharge forms and furloughs for the crowd of soldiers wanting to claim them as their units were spontaneously disbanding. This weekend a friend of mine from Houston Civil War Roundtable shared with me a document held by his family, the discharge paper issued to one of his ancestors, Private John A. Stevens of Company G, Thirty-fifth Texas Dismounted Cavalry. According to family lore, Stevens’ company commander, Captain G. E. Warren, managed to grab a sheaf of blank discharge forms from headquarters and then put his company on the northbound train of the Houston & Texas Central. Captain Warren’s intent was apparently to keep them together as a unit and out of trouble and get them out of Houston and on their way to their homes. Warren took them on the train all the way to Navasota (near the end of the railroad at Millican) and, only after arriving there, filled out the soldiers’ discharge papers and released them to make their way home. Private Stevens is said to have carried this discharge form on his person for many years after.

It’s wonderful to see a tangible document of this sort, it helps corroborate a story like this. It helps make the collapse of the Confederacy in Texas that much more real, at least for me. Thanks to my friend for sharing this with me.

_______

Hood’s Texas Brigade Association, Re-activated Meeting, December 1-2 in Galveston

I am pleased to announce that I will be speaking on blockade running off the Texas Coast on the evening of Friday, December 1, at the annual scholarly seminar of the Hood’s Texas Brigade Association, Re-activated (HTBAR) in Galveston. Registration for the seminar is open through November 27, using the attached form (PDF). A complete schedule of events is included in the registration materials.

I am pleased to announce that I will be speaking on blockade running off the Texas Coast on the evening of Friday, December 1, at the annual scholarly seminar of the Hood’s Texas Brigade Association, Re-activated (HTBAR) in Galveston. Registration for the seminar is open through November 27, using the attached form (PDF). A complete schedule of events is included in the registration materials.

The main presenters at this year’s seminar, recognizing the 50th Anniversary of HTBAR, are top-notch in their field, and always worth hearing:

- Dr. Susannah Ural: “Hood’s Texans: How the Texas Brigade Became the Confederacy’s Most Celebrated Unit”

- Rick Eiserman: “Fifty Years of Service to Hood’s Brigade”

- Dr. Rick McCaslin: “Remembering Hood’s Texas Brigade: Pompeo Coppini and Confederate Memory”

I’ve had the opportunity to hear each of these speakers before, and this is an event no one should miss if they have an interest in Hood’s Brigade. I look forward to renewing some old acquaintances there, and making some new ones.

_____

The Texas Confederate on Boot Hill

In recognition of Thursday’s anniversary of the Gunfight at the OK Corral, an old post from 2014. . . .

______

There’s always a new angle on an old story, isn’t there?

There’s always a new angle on an old story, isn’t there?

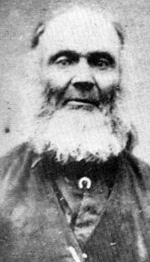

This past weekend there was a post by a member over at Civil War Talk who recently visited Tombstone, Arizona, and was surprised to see a small Confederate flag marking the grave of one of that location’s better-known, um, residents. Newman Haynes “Old Man” Clanton (right, c. 1880) was the father of Ike and Billy Clanton, part of the “Cowboy” faction that ran afoul of the Earp brothers in Tombstone in 1881. When the Earps, along with the tubercular dentist Doc Holliday confronted the Cowboys at the OK Corral in late October 1881, Ike happened to be unarmed and ran off; Billy stayed and died, shot through the right wrist and in the chest and abdomen.

Old Man Clanton didn’t live to see his son killed in that famous shoot-out; Newman had himself been shot down a few months before in an ambush while herding stolen cattle through the Guadalupe Canyon, at the extreme southern end of the Arizona/New Mexico border. In truth, all the Clantons had a long reputation as troublemakers and small-time criminals, mostly involving cattle rustling, often with animals stolen from across the border in Mexico. Ike Clanton himself would be killed in a shoot-out with a detective attempting to arrest him on rustling charges in 1887; his violent end probably surprised exactly no one.

The family was originally from Missouri, but resettled in Texas in the 1850s. At the time of the 1860 U.S. Census, Newman Haynes Clanton and his family were were farming or ranching in Dallas County. He and his wife, Maria (or Mariah), had six children living with them, including twelve-year-old Joseph Isaac Clanton, later known as Ike. Two more children, including Billy, would be born after 1860.

Clanton’s Civil War service record, as documented by his file at the National Archives (8.3MB PDF), is spotty. He appears to have enlisted as a Private in Co. K of the First Texas Heavy Artillery Regiment at Waco on March 1, 1862, for a period of one year. In May 1862 he was on detached duty at Hempstead, Texas, employed as a nurse. He was discharged on July 6 as being overage; he would have been in his mid-40s. He re-enlisted at Fort Hébert, near Galveston, on January 1, 1863, the day of the Battle of Galveston, ostensibly for the duration of the war. Clanton apparently had other plans, though, because his record shows him as absent without leave from that date, and marked as a deserter from March 2, 1863.

In ealry 1864, Clanton joined an unknown Texas State Militia unit which was probably occupied paroling the frontier. He went into the U.S. Provost’s headquarters at Franklin, Texas (north of present-day Bryan and College Station) on August 26, 1865 and swore out his allegiance to the United States. Just eight days later, on September 3, 1865, Clanton arrived at Fort Bowie, Arizona Territory, with (as his record notes) “persons now at Fort Bowie, Arizona Territory, enroute to California, who formerly belonged to the Confederate States Army.” The speed of Clanton’s travel — roughly 850 miles in eight days — strongly suggests he went by stagecoach, rather than on his own horse or by wagon. Even so, it would have been an unusually fast stagecoach ride; the pre-war Butterfield Overland Express traveled roughly that same route, and didn’t make as good a time as Clanton would have had to in the summer of 1865.

Or maybe, as CWT user Nathanb1 suggests, he wasn’t in both places at all. The NARA records, ostensibly made just over a week apart, almost describe different middle-aged men:

![]()

Same man at Franklin, Texas on August 26, and then at Fort Bowie, Arizona Territory on September 3? It’s hard to see how. But if anyone was the sort to have some unknown scheme, it would be Newman Haynes Clanton.

___________

Boot Hill grave site image via Find-a-Grave.

Mark Antony Waves the Bloody Shirt

Click-click-clicking through YouTube videos, I happened on this one, of Charlton Heston’s performance of the famous “friends, Romans, countrymen” speech from Julius Caesar. It’s the first time, I think, I’ve seen it performed, and it makes a striking difference from simply reading the text, or listening to a recitation of it.

“. . . and Brutus is an honorable man.” That, my friends, Romans, countrymen, is how you turn the knife in the wound.

______

2 comments