Texas (and Japanese) Reenactors at Gettysburg

There’s a great series of press images of the 150th anniversary reenactment of Gettysburg, here. Here are two of my favorites:

![]()

Mike Wilkinson, of San Antonio, portraying a soldier with the 4th Texas Infantry, smokes a pipe during ongoing activities commemorating the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, Thursday, June 27, 2013, in Gettysburg, Pa. Photo: Matt Rourke, Associated Press / AP

Satomi Okada, 52, pulls her hair back as she transfers chicken thighs from a cast iron skillet to a soup pot under the guidance of re-enactor Candy Girard, 62 of Omaha, Neb., at the Blue Gray Alliance’s re-enactment camp outside Gettysburg, Pa., on Friday, June 28, 2013. Okada, who is from Kobe, Japan, has a three-month tourist visa and is trying to learn what she can about the Civil War, which in Japan is called “the North-South War.” A Minnesota friend of hers is re-enacting, and brought her along for the ride. Okada will be a “powder monkey” — assisting with the cannons — with Terry’s Texas Rangers Company H during the re-enactments. Some women did go to war — incognito — with their brothers, fathers or husbands during the Civil War, and more than a few female re-enactors today are portraying that by abandoning the hoop skirts and petticoats in favor of men’s wear and artillery. Daily Record/Sunday News — Chris Dunn.

I wonder if that second caption is garbled, since Terry’s Rangers weren’t anywhere near Gettysburg, and had no artillery. Regardless, looks like great fun. When do we eat?

____________

More on Sam Cullom

As a follow-up to my recent post on Sam Cullom, a reader passes along this 2004 news item on a ceremony held at the cemetery in Livingston. From the Cookeville, Tennessee Herald-Citizen, July 17, 2004:

Black Confederate soldier honored in ceremony Sam Cullom’s army service memoralized at Livingston

Black Confederate soldier honored in ceremony Sam Cullom’s army service memoralized at Livingston

A memorial service was held last Sunday at Livingston for a former slave who served as a soldier in the Confederate Army.

Descendants of Sam Cullom attended the ceremony, sponsored by the Highland Brigade of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the Sally Tompkins chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, at the Bethlehem Methodist Church, near the Overton County Fairgrounds. Keynote speaker was Ed Butler of Cookeville, commander of the Tennessee Division of the SCV.

At the outbreak of the War Between the States, Sam Cullom was a slave belonging to Alvin Cullom who lived in Overton County.

Sam and Alvin’s son, Jim, joined the 25th Tennessee Infantry and served with the Army of Tennessee at battles in Kentucky, Tennessee and Georgia.

At the battle of Atlanta, Jim was killed in action, and Sam buried him. Sam then was granted leave and brought home to Overton County the personal effects of the young soldier. Sam then joined the 8th Tennessee Cavalry and served through the rest of the war.

The exact spot where Sam Cullom is buried in the Bethlemen cemetery is lost to history.

Cullom’s early story sketchy because of poor records keeping of the day, but he stated in his Confederate pension application that he had been born in Maryland.

Overton County Historian Ronald Dishman said he suspects that Alvin Cullom, a judge and member of Congress, bought Sam from George and William Cullom, tobacco farmers who came from Maryland.

Congressman Cullom’s family lived near Monroe, north of Livingston, but in later years moved to the Bethlehem area, off what is now Hwy. 84, between Monterey and Livingston.

Sam Cullom’s Confederate pension application indicates that he came to Tennessee when he was about 9-years old.

There had been a Bethlehem Methodist congregation since around 1801, Oprha Hassell, church historian, said, but Alvin Cullom gave land to build the church and lay out a cemetery were it now stands. The large cemetery adjacent to the church is where the Cullom family, both white and black, including the congressman and his slave, Sam, are buried.

Congressman Cullom was a part of a peace delegation that tried to avert the tragic War Between the States but to no avail. When war did break out, Sam was sent away to the Confederate army with Alvin Cullom’s sons, Jim and Ras.

Sam, long with Jim and Ras, served in the 8th Infantry Regiment of the Confederate States of America. They were assigned to Capt. Calvin E. Myer’s Co. D, which later became Co. F. James Cullom eventually became captain of that company.

Mustered into Confederate service on July 31, 1861, at Big Springs, Va., the 8th Infantry subsequently took part in the Cheat Mountain Campaign; fought at Corinth, Miss.; at Munfordville and Perryville, Ky.; and at Murfreesboro, Chickamauga and Missionary Ridge in Tennessee.

After the war, Sam returned home and described for the Alvin Cullom family how their son, Capt. Jim Cullom, was killed in the Atlanta fighting, telling them how it was he who had buried their son.

It wasn’t until 1921, when Sam was around 80-years old, that he applied for a Confederate pension after the Tennessee General Assembly passed the “Negro Pension Law.” By then, he had seven children and several grandchildren, and he and wife were living in the home of their son, Mack, a noted blacksmith of the Livingston area.

It is not known how many African American served as Confederate soldiers but it is clear that the Confederate Army did include blacks, even those listed as “free men of color,” within their ranks.

“Because the North won the war,” Ed Butler said in his address, “they got to write the history books. They would have you believe that all the blacks in the Confederate Army were cooks or valets.”

Butler gave an example of a White County Confederate soldier, Churchwell Randals, who was black and who attained the rank of corporal. “You wouldn’t attain that rank by being a cook or a valet,” he said.

“Slavery was an abomination which should have been done away with many years before it was,” Butler said. He pointed out a fact, omitted from some history books, that even Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant had slaves — and he didn’t free them until Dec. 1865, after the 13th Amendment to the Constitution was passed, several months after the war had ended.

One of Sam Cullom’s descendants, Dr. Althea Armstrong, Sam Cullom’s great-granddaughter from Detroit, Mich., also spoke at the memorial service.

“This is an historical moment in America,” she said. “Where I come from, the population is 90-percent black. Here, it is 98-percent white. But here we are. It is not a black thing or a white thing. Today it is about freedom.”

![]()

What should we make of this? What parts of Sam Cullom’s story changed between this news item in 2004, and the one four years later? Are different claims made, and how does either square against the contemporary historical record? Are there themes or arguments in this story we’ve heard before?

___________

“Southern people have not gotten over the vicious habit of not believing what they don’t wish to believe”

We recently looked at an editorial from the Atlanta Southern Confederacy, arguing loudly against the arming of slaves during the winter of 1864-65. But that view was not universal. The governor of Virginia, William “Extra Billy” Smith (right, 1797-1887), was one of the first prominent Confederate office-holders to urge the Confederate congress to seriously consider the idea, calling upon them to “give this subject early consideration, and enact such measures as their wisdom may approve.” Smith’s call was taken up by an editorial in the Charlottesville Chronicle, that was reprinted in the Richmond Sentinel just before Christmas 1864:

We recently looked at an editorial from the Atlanta Southern Confederacy, arguing loudly against the arming of slaves during the winter of 1864-65. But that view was not universal. The governor of Virginia, William “Extra Billy” Smith (right, 1797-1887), was one of the first prominent Confederate office-holders to urge the Confederate congress to seriously consider the idea, calling upon them to “give this subject early consideration, and enact such measures as their wisdom may approve.” Smith’s call was taken up by an editorial in the Charlottesville Chronicle, that was reprinted in the Richmond Sentinel just before Christmas 1864:

________

[1] Richmond Sentinel, December 21, 1864. Quoted in Robert F. Durden, The Gray and the Black: The Confederate Debate on Emancipation (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1972), 146-47.

Research Exercise: “Sam Cullom, Black Confederate”

The name Sam Cullom is a new one to me, but it seems he’s been celebrated in and around Livingston, Tennessee as a local Black Confederate for a while. A military-style headstone was placed over his grave about ten years ago (right), with the legend, “Pvt. Sam Cullom.” His story is told a number of places, like this 2008 piece in the Crossville, Tennessee Chronicle:

The name Sam Cullom is a new one to me, but it seems he’s been celebrated in and around Livingston, Tennessee as a local Black Confederate for a while. A military-style headstone was placed over his grave about ten years ago (right), with the legend, “Pvt. Sam Cullom.” His story is told a number of places, like this 2008 piece in the Crossville, Tennessee Chronicle:

So here’s an assignment for those who may be so inclined. See what you can find in the way of historical documentation that supports or refutes this profile of Cullom. To get you started, here’s his 1921 pension application from the State of Tennessee, and his listing in the decennial U.S. Census for 1880, 1900, 1910 and 1920 (two pages).

Please feel to post links to other, primary sources that are useful in documenting Cullom’s life. Have fun.

“They constitute a privileged class in the community”

![]()

In January 1865 the debate over whether to arm slaves in a last-ditch defense against the Union army was coming to a head in Richmond. The measure would eventually pass a few weeks later, in mid-March. Nonetheless, the Atlanta Southern Confederacy, publishing in Macon, continued to reject the notion that African American should, or even could, be put under arms.

![]()

Keep in mind that on the date this was published, January 20, 1865, Uncle Billy’s troops were marching north from Savannah into South Carolina, Fort Fisher had just been captured, closing the last Confederate port on the Atlantic, and U.S. Speaker of the House Schuyler Colfax was lobbying hard for votes to pass the 13th Amendment in Congress. Yet down in Macon, the local editor was devoting column inches to explaining how slaves were a “privileged class,” happy and contented folks, unburdened by anxiety or want: “how happy we should be were we the slave of some good and provident owner.”

You may bang your head on the desk now.

____________

[1] Atlanta Southern Confederacy, January 20, 1865. Quoted in Robert F. Durden, The Gray and the Black: The Confederate Debate on Emancipation (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1972), 156-58. Image: “Market Scene in Macon, Georgia,” by A. R. Waud. From here.

Talkin’ Buffalo Bayou Steamboats

On Sunday afternoon I’ll be talking about one of my favorite topics again, Texas riverboats. Before the railroad, before the Interurban, before the scourge of construction detours on the Gulf Freeway, Galveston and Houston were first linked by steamboat. The water link between the two cities helped establish both towns as the fastest-growing, booming communities in the state of Texas during the 19th century. The tale, largely overlooked until now, is one of cut-throat competition, horrific accidents, hard-fought battles and more.

Sunday, June 23 at 2 p.m.

Menard Campus, 3302 Avenue O

Galveston, Texas

Admission is $10 for Galveston Historical Foundation members, $12 for non-members.

______________

Image: Sternwheeler St. Clair at the Houston landing, c. 1867. Houston Public Library.

Hari Jones Drops the Hammer on National Observance of Juneteenth

[This post originally appeared on June 20, 2011.]

Hari Jones, Curator of the African American Civil War Museum, drops the hammer on the movement to make Juneteenth a national holiday, and the organization behind it, the National Juneteenth Observance Foundation (NJoF). He argues that the narrative used to justify the propose holiday does little to credit African Americans with taking up their own struggle, and instead presents them as passive players in emancipation, waiting on the beneficence of the Union army to do it for them. Further, he presses, the standard Juneteenth narrative carries forward a long-standing, intentional effort to suppress the story of how African Americans, in ways large and small, worked to emancipate themselves, particularly by taking up arms for the Union. He wraps up a stem-winder:

Certainly, informed and knowledgeable people should not celebrate the suppression of their own history. Juneteenth day is a de facto celebration of such suppression. Americans, especially Americans of African descent, should not celebrate when the enslaved were freed by someone else, because that’s not the accurate story. They should celebrate when the enslaved freed themselves, by saving the Union. Such freedmen were heroes, not spectators, and their story is currently being suppressed by the advocates of the Juneteenth national holiday. The Emancipation Proclamation did not free the slaves; it made it legal for this disenfranchised, enslaved population to free themselves, while maintaining the supremacy of the Constitution, and preserving the Union. They became the heroes of the Republic. It is as Lincoln said: without the military help of the black freedman, the war against the South could not have been won. That’s worth celebrating. That’s worth telling. The story of how Americans of African descent helped save the Union, and freed themselves. Let’s celebrate the truth, a glorious history, a story of a glorious march to Liberty.

![]()

Jones makes a powerful argument, with solid points. But I think he misses something crucial, which is that in Texas, where Juneteenth originated, it’s been a regular celebration since 1866. It is not a modern holiday, established retroactively to commemorate an event in the long past; the celebration of Juneteenth is as old as emancipation itself. It was created and carried on by the freedmen and -women themselves:

![]()

Some of the early emancipation festivities were relegated by city authorities to a town’s outskirts; in time, however, black groups collected funds to purchase tracts of land for their celebrations, including Juneteenth. A common name for these sites was Emancipation Park. In Houston, for instance, a deed for a ten-acre site was signed in 1872, and in Austin the Travis County Emancipation Celebration Association acquired land for its Emancipation Park in the early 1900s; the Juneteenth event was later moved to Rosewood Park. In Limestone County the Nineteenth of June Association acquired thirty acres, which has since been reduced to twenty acres by the rising of Lake Mexia. Particular celebrations of Juneteenth have had unique beginnings or aspects. In the state capital Juneteenth was first celebrated in 1867 under the direction of the Freedmen’s Bureau and became part of the calendar of public events by 1872. Juneteenth in Limestone County has gathered “thousands” to be with families and friends. At one time 30,000 blacks gathered at Booker T. Washington Park, known more popularly as Comanche Crossing, for the event. One of the most important parts of the Limestone celebration is the recollection of family history, both under slavery and since. Another of the state’s memorable celebrations of Juneteenth occurred in Brenham, where large, racially mixed crowds witness the annual promenade through town. In Beeville, black, white, and brown residents have also joined together to commemorate the day with barbecue, picnics, and other festivities.

![]()

It’s one thing to argue with another historian or community leader about the the historical narrative represented by a public celebration (think Columbus Day), but it’s entirely another to — in effect — dismiss the understanding of the day as originally celebrated by the people who actually lived those events, and experienced them at first hand.

What do you think?

_____________

h/t Kevin. Image: Juneteenth celebration in Austin, June 19, 1900. PICA 05476, Austin History Center, Austin Public Library.

Juneteenth, History and Tradition

[This post originally appeared here on June 19, 2010.]

“Emancipation” by Thomas Nast. Ohio State University.

![]()

Juneteenth has come again, and (quite rightly) the Galveston County Daily News, the paper that first published General Granger’s order that forms the basis for the holiday, has again called for the day to be recognized as a national holiday:

Those who are lobbying for a national holiday are not asking for a paid day off. They are asking for a commemorative day, like Flag Day on June 14 or Patriot Day on Sept. 11. All that would take is a presidential proclamation. Both the U.S. House and Senate have endorsed the idea. Why is a national celebration for an event that occurred in Galveston and originally affected only those in a single state such a good idea? Because Juneteenth has become a symbol of the end of slavery. No matter how much we may regret the tragedy of slavery and wish it weren’t a part of this nation’s story, it is. Denying the truth about the past is always unwise. For those who don’t know, Juneteenth started in Galveston. On Jan. 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation was issued. But the order was meaningless until it could be enforced. It wasn’t until June 19, 1865 — after the Confederacy had been defeated and Union troops landed in Galveston — that the slaves in Texas were told they were free. People all across the country get this story. That’s why Juneteenth celebrations have been growing all across the country. The celebration started in Galveston. But its significance has come to be understood far, far beyond the island, and far beyond Texas.

![]()

This is exactly right. Juneteenth is not just of relevance to African Americans or Texans, but for all who ascribe to the values of liberty and civic participation in this country. A victory for civil rights for any group is a victory for us all, and there is none bigger in this nation’s history than that transformation represented by Juneteenth.

But as widespread as Juneteenth celebrations have become — I was pleased and surprised, some years ago, to see Juneteenth celebration flyers pasted up in Minnesota — there’s an awful lot of confusion and misinformation about the specific events here, in Galveston, in June 1865 that gave birth to the holiday. The best published account of the period appears in Edward T. Cotham’s Battle on the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston, from which much of what follows is abstracted.

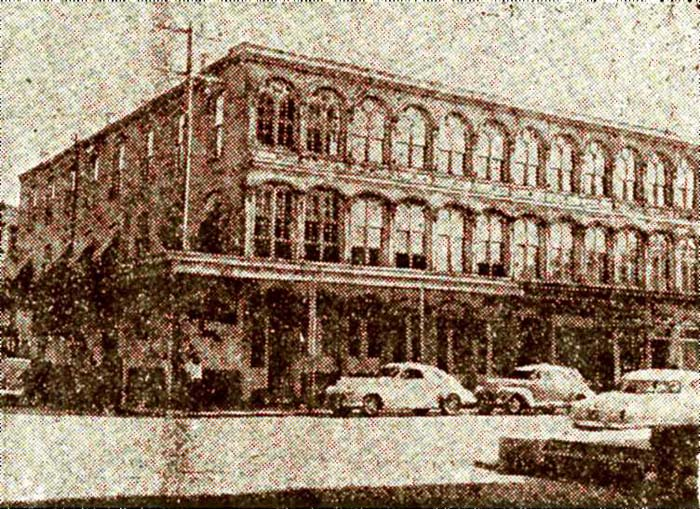

The United States Customs House, Galveston.

![]()

On June 5, Captain B. F. Sands entered Galveston harbor with the Union naval vessels Cornubia and Preston. Sands went ashore with a detachment and raised the United States flag over the federal customs house for about half an hour. Sands made a few comments to the largely silent crowd, saying that he saw this event as the closing chapter of the rebellion, and assuring the local citizens that he had only worn a sidearm that day as a gesture of respect for the mayor of the city.

The 1857 Ostermann Building, site of General Granger’s headquarters, at the southwest corner of 22nd Street and Strand. Image via Galveston Historical Foundation.

![]()

A large number of Federal troops came ashore over the next two weeks, including detachments of the 76th Illinois Infantry. Union General Gordon Granger, newly-appointed as military governor for Texas, arrived on June 18, and established his headquarters in Ostermann Building (now gone) on the southwest corner of 22nd and Strand. The provost marshal, which acted largely as a military police force, set up in the Customs House. The next day, June 19, a Monday, Granger issued five general orders, establishing his authority over the rest of Texas and laying out the initial priorities of his administration. General Orders Nos. 1 and 2 asserted Granger’s authority over all Federal forces in Texas, and named the key department heads in his administration of the state for various responsibilities. General Order No. 4 voided all actions of the Texas government during the rebellion, and asserted Federal control over all public assets within the state. General Order No. 5 established the Army’s Quartermaster Department as sole authorized buyer for cotton, until such time as Treasury agents could arrive and take over those responsibilities.

It is General Order No. 3, however, that is remembered today. It was short and direct:

Headquarters, District of Texas

Galveston, Texas, June 19, 1865 General Orders, No. 3 The people are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property, between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them, becomes that between employer and hired labor. The Freedmen are advised to remain at their present homes, and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts; and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere. By order of

Major-General Granger

F. W. Emery, Maj. & A.A.G.

![]()

What’s less clear is how this order was disseminated. It’s likely that printed copies were put up in public places. It was published on June 21 in the Galveston Daily News, but otherwise it is not known if it was ever given a formal, public and ceremonial reading. Although the symbolic significance of General Order No. 3 cannot be overstated, its main legal purpose was to reaffirm what was well-established and widely known throughout the South, that with the occupation of Federal forces came the emancipation of all slaves within the region now coming under Union control.

The James Moreau Brown residence, now known as Ashton Villa, at 24th & Broadway in Galveston. This site is well-established in recent local tradition as the site of the original Juneteenth proclamation, although direct evidence is lacking.

![]()

Local tradition has long held that General Granger took over James Moreau Brown’s home on Broadway, Ashton Villa, as a residence for himself and his staff. To my knowledge, there is no direct evidence for this. Along with this comes the tradition that the Ashton Villa was also the site where the Emancipation Proclamation was formally read out to the citizenry of Galveston. This belief has prevailed for many years, and is annually reinforced with events commemorating Juneteenth both at the site, and also citing the site. In years past, community groups have even staged “reenactments” of the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation from the second-floor balcony, something which must surely strain the limits of reasonable historical conjecture. As far as I know, the property’s operators, the Galveston Historical Foundation, have never taken an official stand on the interpretation that Juneteenth had its actual origins on the site. Although I myself have serious doubts about Ashton Villa having having any direct role in the original Juneteenth, I also appreciate that, as with the band playing “Nearer, My God, to Thee” as Titanic sank beneath the waves, arguing against this particular cherished belief is undoubtedly a losing battle.

Assuming that either the Emancipation Proclamation (or alternately, Granger’s brief General Order No. 3) was formally, ceremonially read out to the populace, where did it happen? Charles Waldo Hayes, writing several years after the war, says General Order No. 3 was “issued from [Granger’s] headquarters,” but that sounds like a figurative description rather than a literal one. My bet would not be Ashton Villa, but one of two other sites downtown already mentioned: the Ostermann Building, where Granger’s headquarters was located and where the official business of the Federal occupation was done initially, or at the United States Customs House, which was the symbol of Federal property both in Galveston and the state as a whole, and (more important still) was the headquarters of Granger’s provost marshal, Lieutenant Colonel Rankin G. Laughlin (right, 1827-78) of the 94th Illinois Infantry. It’s easy to imagine Lt. Col. Laughlin dragging a crate out onto the sidewalk in front of the Customs House and barking out a brief, and somewhat perfunctory, read-through of all five of the general’s orders in quick succession. No flags, no bands, and probably not much of a crowd to witness the event. My personal suspicion is that, were we to travel back to June 1865 and witness the origin of this most remarkable and uniquely-American holiday, we’d find ourselves very disappointed in how the actual events played out at the time.

Assuming that either the Emancipation Proclamation (or alternately, Granger’s brief General Order No. 3) was formally, ceremonially read out to the populace, where did it happen? Charles Waldo Hayes, writing several years after the war, says General Order No. 3 was “issued from [Granger’s] headquarters,” but that sounds like a figurative description rather than a literal one. My bet would not be Ashton Villa, but one of two other sites downtown already mentioned: the Ostermann Building, where Granger’s headquarters was located and where the official business of the Federal occupation was done initially, or at the United States Customs House, which was the symbol of Federal property both in Galveston and the state as a whole, and (more important still) was the headquarters of Granger’s provost marshal, Lieutenant Colonel Rankin G. Laughlin (right, 1827-78) of the 94th Illinois Infantry. It’s easy to imagine Lt. Col. Laughlin dragging a crate out onto the sidewalk in front of the Customs House and barking out a brief, and somewhat perfunctory, read-through of all five of the general’s orders in quick succession. No flags, no bands, and probably not much of a crowd to witness the event. My personal suspicion is that, were we to travel back to June 1865 and witness the origin of this most remarkable and uniquely-American holiday, we’d find ourselves very disappointed in how the actual events played out at the time.

Maybe the Ashton Villa tradition is preferable, after all.

![]()

Update, June 19: Over at Our Special Artist, Michele Walfred takes a closer look at Nast’s illustration of emancipation.

![]()

Update 2, June 19: Via Keith Harris, it looks like retiring U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison supports a national Juneteenth holiday, too. Good for her.

![]()

Update 3, June 19, 2013: Freedmen’s Patrol nails the general public’s ambivalence about Juneteenth:

![]()

![]()

Exactly right.

______________

Three Years, 300K Views

Today is the 3rd anniversary of Dead Confederates going online. We also just recently — on June 7, to be exact — crossed the mark of three hundred thousand pageviews. I hope this blog has been as enjoyable for my readers as it has been for me.

Today is the 3rd anniversary of Dead Confederates going online. We also just recently — on June 7, to be exact — crossed the mark of three hundred thousand pageviews. I hope this blog has been as enjoyable for my readers as it has been for me.

A while back I added a section to the right-hand sidebar, called “Top Posts & Pages.” It’s been interesting to watch. Naturally, the most recent posts are up there, but I’ve been very pleased at some of the older posts that show up there, that are still getting read months or years after they originally went up. These old posts include:

![]()

- “Ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave,” April 28, 2011

- Non-Slaveholders’ Stake in Defending the “Peculiar Institution,” May 4, 2011

- Nathan Bedford Forrest Joins the Klan, December 11, 2011

- Oh, About that Black Confederate at Arlington. . . , October 23, 2010

- Old Pete, Slave Raids, and the Gettysburg Campaign, July 1, 2010

- How — And Why — Real Confederates Endorsed Slave Pensions, June 13, 2012

![]()

These are, from my perspective, some of the more substantive and worthwhile posts I’ve put down over the last three years. If Dead Confederates makes a real contribution at all to public understanding of the war, it’s posts like those that do the heavy lifting. I’m glad they’re still attracting eyeballs.

__________

The (Very) Posthumous Enlistment of “Private” Clark Lee

Kevin and Brooks have been all over the Georgia Civil War Commission, and particularly of its handling of the case of Clark Lee, “Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier.” I won’t rehash all of that, but there are a few points to add.

Kevin and Brooks have been all over the Georgia Civil War Commission, and particularly of its handling of the case of Clark Lee, “Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier.” I won’t rehash all of that, but there are a few points to add.

First, kudos to Eric Jacobson, who noticed that the modern painting of Lee used by the commission on its marker (right) is almost laughably tailored to affirm Lee’s status as a soldier, including the military coat with trim and brass buttons, rifle, cartridge box belt, military-issue “CS” belt buckle, and revolver, all backed by a Confederate Battle Flag — even though the Army of the Tennessee didn’t adopt that flag until the appointment of General Joseph E. Johnston, well after the Battle of Chickamauga.

It’s probably also worth noting that the man in the painting looks a lot older than 15, the age the Georgia Civil War Commission says Lee was at the time of the battle.

As it turns out, several weeks ago the SCV and other heritage folks installed and dedicated a new headstone for Lee, explicitly (and posthumously) giving him the military rank of Private. The stone also states that Lee “fought at” Chickamauga, Lookout Mountain, the Atlanta Campaign, and a host of other engagements by the Army of Tennessee. These are very specific claims, so it’s worth asking what the specific evidence for them is.

![]()

E. Raymond Evans (center, with umbrella), author of The Life and Times of Clark Lee: Chickamauga’s Black Confederate Soldier, speaking at an SCV memorial service for Clark Lee in April 2013. From here.

![]()

As is so often the case, there doesn’t appear to be any contemporary (1861-65) record of Lee’s service. There is no compiled service record (CSR) for him at the National Archives. Presumably the historical marker, the headstone, and a recent privately-published work on Clark Lee are all based on his 1921 application for a pension from the State of Tennessee, where he had moved in the years after the war. You can read Lee’s complete pension application here (29MB PDF). I cannot find a word in it that mentions or describes Clark Lee’s service under arms, or in combat. There is a general description of Lee’s wartime activities, but it’s quite different from what the Georgia Civil War Commission wants the rest of us to understand about him. I’ve put it below the jump because of some of the unpleasant themes expressed.

8 comments