Research a Mile Wide, and an Inch Deep

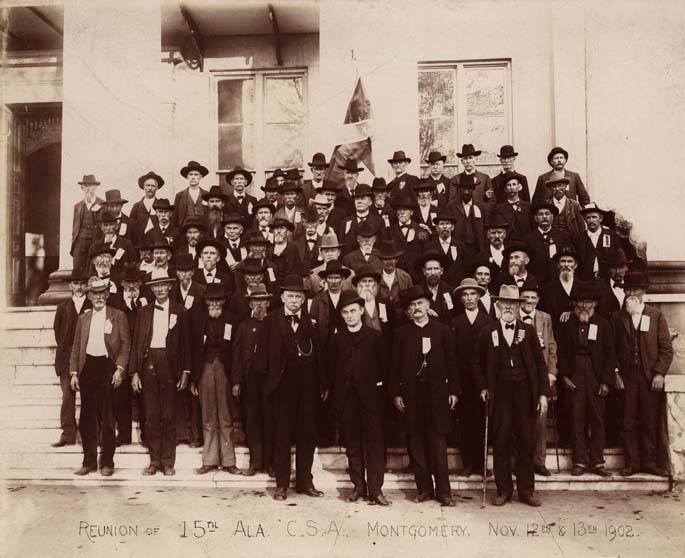

The deeply shallow “research” to prove the existence of black Confederates continues apace. This image, from the Alabama Department of Archives and History, is of men from the 15th Alabama Infantry attending a statewide Confederate veterans reunion in Montgomery, in November 1902. The 15th Alabama, many will recall, is the regiment that made repeated attempts to dislodge the Union flank on Little Round Top on the second day at Gettysburg, facing the famous 20th Maine Infantry. I believe the former commander of the 15th Alabama, William C. Oates, is the first man at left in the front row in the image, directly above the C in “C.S.A.”

The image has become a point of discussion online recently, particularly in reference to the dark-skinned man in the second-to-last row, third from the end on the right. The discussion seems to center around whether the man is African American, of mixed race, or perhaps is a white man with very dark, tanned skin. Whether he’s actually African American or not is critical, because the beginning and end of the question is whether or not a black man attended a Confederate reunion. That fact, in and of itself, is apparently supposed to tell us all we need to know about African Americans and the Confederacy.

Of course, it doesn’t.

Warning: The following includes historical quotes that use offensive language and themes.

As I’ve pointed out many times before (see here, and here, and here, and. . .), the photos of elderly African American men at Confederate reunions are common enough, but say little in and of themselves. When you look past the initial images and dig into contemporary accounts of these events, you will almost invariably see that these black men were not discussed as veterans co-equal with the white soldiers, but were welcomed when their presence re-affirmed their wartime roles, usually as personal servants or cook. While there’s no question that there was some genuine affection and a feeling of bonhomie, they were also identified as a group apart from the white veterans, and were often seen as subjects of gentle ridicule. In the larger scheme of old Confederates’ commemoration of the war, these old black men were presented as living embodiment of the faithful slave, reinforcing Southern narratives about the benign nature of slavery and close bonds between slaves and their masters, depicted as warm but always paternalistic, and never as equals. Even such well-known Confederates as John B. Gordon, one of Lee’s corps commanders and the first commander-in-chief of the UCV, spoke of them as a distinct group, separate and apart from the white former soldiers, describing them as “faithful servants” who “meet now with the veterans in their reunions.”[1] Gordon describes these elderly black men not as veterans in their own right, but who join “with the veterans” at reunions.

Contemporary coverage of the Alabama reunion in 1902 was no different. While the man in the 15th Alabama image is not identified, the larger reunion received considerable coverage, including the presence of African Americans. This description, from the Montgomery Advertiser of November 14, is entirely typical of the way African Americans were engaged and depicted at Confederate reunions:

After the 15th Regiment came the Montgomery Military Band, followed closely by the Fourth Brigade, General J. W. Bush of Birmingham, commanding his staff, sponsors and maids of honor.

Then a company of wartime body servants of various soldiers came. The old negroes [sic.] were of the purest type of the Southern darkey. Joy shone in the face of every one as they tottered after their former masters just as they followed them in the olden days.

With one exception the negroes were all stooped and feeble. This exception was Mike Beauregard, an old Greenville negro, who served throughout the entire war. Beauregard was in full regimentals, epauletted and brass buttoned. He clanked a heavy artillery sabre and marched his little band of darkies as proud as a Napoleon.[2]

Note that this is not some newspaper “spin” on the event; it describes how the veterans themselves organized the public parade, complete with a caricatured officer, “as proud as a Napoleon”, leading “his little band” of former body servants. Mike Beauregard (c. 1833-1906) seems to have been a regular feature at such reunions, performing a role in much the same way that Steve Perry did later as “Uncle Steve Eberhart”, or Mississippian Howard Divinity, billed as the “Champion Chicken Thief of the Confederate Army.”[3] These are not men who were being honored for their wartime service, so much as applauded for their roles as entertainers.

My point here is not to denigrate African American men who attended Confederate reunions. They were likely motivated by numerous factors, including the genuine and sincere desire to renew old acquaintances and reminisce about the tumultuous experiences of those years. But they also reinforced the postwar Southern narrative of the war, being held out as examples “of the purest type” of former slave. Even men like Mike Beauregard and Steve Perry, who took on more visible roles as entertainers, undoubtedly understood what they were doing. They made their own calculations. (One of my readers observed of Steve Perry, “the things we do to get by.”)

Rather, my criticism is for those today who take a fragment of the historical record – a photograph of a black man at a reunion, in this case – and use it to spin all sorts of warm-and-fuzzy “observations” about their Confederate forebears, real or figurative. They play these images like a trump card – “there, black Confederate, see?” – while studiously avoiding the more complex work of looking at the context of the image, and the way such activities were seen and understood at the time. Images like that of the 15th Alabama are not the conclusion of research; they’re the beginning of it. Such claims do nothing to honor these men, as men. It is simply an extension of the time-honored “faithful slave” narrative, updated to make it more palatable to a modern audience. The black Confederate narrative now so diligently espoused by the Southron Heritage™ movement is whitewashing, historical revisionism of the rawest sort, an effort to project modern, political correctness back onto men who would laugh out loud at the claims now being made on their behalf.[4]

It’s ridiculous, it’s lazy, and it presents a fundamentally dishonest portrait of those men, black and white, who lived so long ago. If you want to honor them, then do the work necessary to tell their stories, in all their complexities and contradictions.

[1] John B. Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904), 383.

[2] Montgomery Advertiser, 14 November 1902, p. 7, c. 3.

[3] Beauregard’s obituary describes him as “an odd character and devoted to military affairs. At all military encampments where the Greenville company participated, he was on hand to wait on the boys, and in all parades here he was a conspicuous figure. Dressed in an officer’s uniform, with epaulets and a sword, he headed many processions, and, twirling a stick as he kept step, he attracted the attention of all the children. He had many friends among the white people.” Montgomery Advertiser, 25 February 1906, p. 24, c. 5.

[4] General Oates, who posed in that 1902 reunion photo, was later eulogized as a man who “threw himself in[to] the reconstruction struggle for the re-establishment of the white man’s government” and “was a prominent participant in the conferences which planned the desperate struggles against the carpet-baggers and their negro [sic.] dupes. . . and he was one of the boldest and ablest leaders of the white man’s party within the Legislature.” Montgomery Advertiser, 10 September 1910, p. 2, c. 4.

______________

Fantastic as always Andy!

One of my great grandfathers was a Confederate soldier, and in all individual photos of him (perhaps originally from tintypes) he appears slightly darker than other family members in their individual photos. One photo is slightly darker that the aforesaid others; perhaps a hint that he might not be pure white, but far from conclusive. One of his last photos was a Wilmington Confederate group photo, and in it, he looks as white as other whites.

His father was Shadrack Wooten of Pitt County, N.C., a grandson or great grandson of Shadrack Johnson of of Johnson Mills, Pitt County, who like the Wootens is believed to be from Isle of Wright County, Virginia; I would guess circa 1700? From there, plus another hundred years back, that might get him to a white settler Mr. Johnson of Jamestown, Virginia; who purchased the years of service (common to then white indentured servants, most of who’s trans-Atlantic passage was voluntary, whilst the first load of Africans to Jamestown; I think were forced) passage indenture of a presumably industrious, intelligent African who learned a craft, fulfilled his indenture, took his former white master’s name; and wed Mr. Johnson’s daughter.

Mean-while, black indentures evolved legally, into legal slavery; and the African Johnson, allegedly had his own slaves.

Likely there was more social and economic gain if the free mulatto Johnson children married “white”. My guess is in four to five generations of added pure white blood, most, or all; vestiges of African features would be subordinated and in the case of a rare exception, the family history suppressed; if still known. Since the black Mr. Johnson seems to have had several white Johnson brother-in-laws; even if the white Shadrack Johnson of 1700 Isle of Wright County, Virginia, was of that Jamestown Johnson family; statistically it’s more likely he was of the white brothers-in-law.

In your Confederate Veteran group photo, while the veteran on the right beginning of the row looks “darkish”, my feeling is he is essentially “white”? But our man in question, in contrast; does look more black than white? Has any recognized forensic photo experts ever reached a decision on this? While the photo would likely “fall-apart” with super enlargement; by then sketching-in; it might more clearly reveal not black or white “color” per se, but reveal African or European facial features?

I don’t know if the man in question here is actually African American; what’s odd is that that’s the focus of the question, presumably because if he is, that “proves” some Great Truth. (We are, or should be, far beyond the point where a black face at a Confederate reunion is a revelation.) The interest in black Confederates rarely extends beyond chalking up another example, and very rarely is any real effort made to dig into the details of historical record, either for specific individuals or as a group. (I suppose I can understand why; look what happened to the legend of “the Chandler Boys” when someone actually started looking at the historical evidence. . . .)

I came to this article because I saw another a little while ago featuring the assertion that “not a single” African American fought for the Confederacy, along with some comments underneath featuring a lot of what appeared to be sound evidence to the contrary.

Ranging from the technicality (that the battalion raised by the Confederacy shortly before its collapse were to some extent involved in a skirmish) to references in the letters of Union officers, and claiming that in one State a census recorded 3,000 Confederate veterans in 1890 who were African-American, it all seemed quite convincingly detailed. Anyway, it made me spot this article when I otherwise would have missed it.

Perhaps this might seem like a naive question, but I always imagined that slaves would be likely to share, to some extent at least, the attitudes and sense of norms that dominated the wider community – just as happens in any society where the poor and disenfranchised usually come to identify with the existing structures of society.

It therefore takes me by surprise to learn that those blacks who were free men in the South did not feel compelled to take any sort of part in public life, or that, if they did, none of them sought to fight for the Confederacy in any way. There must have been people of mixed race, as well, who must have had a complicated relationship with the wider society.

So, I suppose my question is: what about the free black population of the South, small as it was? What was the limit of their participation in the Confederate war effort?

Actually, I have a supplementary question: if slaves were such a good investment in the antebellum period, then why didn’t more Northerners invest? After all, it would be easy enough, today, to invest in stocks, or property, abroad. Were there legal barriers or was it just a lack of financial infrastructure?

The best-known example if the Louisiana Native Guard, a prewar militia unit comprised of Creoles and free African Americans. This unit became active at the beginning of the war, but was never fully equipped with uniforms of weapons. The Confederate government would not take them into national service, and in early 1862 the Louisiana legislature rewrote the laws concerning state militia to exclude men of color, effectively disbanding the unit. Those men wanted to serve, were glad to serve, but both Louisiana and the Confederate authorities essentially brushed them aside.

Also recall that Confederate Army regulations explicitly allowed enlistment of only free white men, in edition issued all the way through 1864.

There were free African Americans who worked in a variety of capacities for the Confederate military, or contracted with them in business.

If the man in the Confederate Veteran group photo is indeed recognize by the vets as “black”; his location within the group and not at it’s fringes, is contrary to Southern social, and even legal proscriptions of that time. It would be slightly surprising if it was a photo of a black veteran and white veteran; but if kept between themselves and families, I could believe in such an exceptional bond; and add three cheers.

But I find that in such a large group of presumedly stereo-typical Southern whites of that time, that none would object over departure from custom; statistically unlikely.

But here is where I suspect you and I differ Andy: I hope that in-fact he was a slave, or free black; if not in, at least with service with the Confederate army, who’s service is being appreciated and honored by others–alas, it’s just not likely. I can understand how blacks today would understandably resent a black’s service with the Confederate army; however I have not walked in his moccasins. And while Supreme Court Justice Thomas sometimes surprises me; had I walked in his moccasins, I too, might arrive at at least some of his views of things?

By-the-way, I understand something very rare has just happened in a Federal Court circuit regarding race. A very senior boss in some chicken processing company, pointedly called a mature black male a “boy”; and I think it was not considered individually discriminatory by the Federal government because he consistently called all mature black male workers “boy”. (Note: my father said his Charlotte, N.C., father (a good man too) called all black males by the same first name only, regardless of their actual names, known or unknown to him. I’ve forgotten that name, except it was not “George” which was commonly used for Pullman sleeping car porters of that era). The court up-held the chicken company boss’s use of “boy” (does that chicken company sell more chicken to whites, than black customers?). A motion was filed to reconsider their opinion in the appeal, and the appeals court reversed itself. I would think even more of that Federal Appeals Court, had the court itself, on it’s own motion; filed to reconsider it’s opinion.

Col. Saunders: these finally majestic magistrates, just earned each their own bucket of your best: from Traditional decision; to an Extra Crispy, one.

Great post Andy.

“…reinforcing Southern narratives about the benign nature of slavery and close bonds between slaves and their masters, depicted as warm but always paternalistic, and never as equals…”

Can we get this on a monument?

“…studiously avoiding the more complex work of looking at the context of the image, and the way such activities were seen and understood at the time.”

So what these folks do is unwittingly reinforce stereotypes of themselves, as less-educated and/or willfully ignorant white southerners. They were outnumbered in 1865, 1965 and they are surely on the wrong side of demographic destiny right now, among a new generation of southerners who see no future in racism and steadily increasing numbers of northerners, who continue to migrate south.

“So what these folks do is unwittingly reinforce stereotypes of themselves, as less-educated and/or willfully ignorant white southerners.”

I won’t go that far, but they aren’t making many inroads among the general public that I can see. And the more dramatic (or dramatized) the outreach, the worse they make themselves look. (Do these guys really think they’re changing hearts and mind by acting like this? I kinda doubt it.) Whether they realize it or not — and I suspect most don’t — the Southron Heritage™ movement is mostly engaged in an internal conversation, reassuring each other of their commitment and dedication, their shared persecution at the hands of a politically-correct world, and rightness of their ancestors’ cause.

The essential question here is why would a group of people prefer to be the property of another group of people – because of a claim to some kind of Southern “heritage” ? I think not. What I think what is going on is a rationalization for the actions of one’s ancestors and also a deep-rooted belief that African-Americans are not as intelligent as their (masters) White counterparts. This type of thinking has likely been going on for generations. I’m not saying all White Southerners think this way, but I have no doubt that those who espouse the views of the disgusting website aforementioned in this post are likely beyond hope.

It’s not nearly as simple as that. (Tired of hearing me say that, yet? 😉 )

In the case of African American men who attended Confederate reunions, it turns out that virtually every one of those men — and every case I’ve seen — was a personal servant to a white soldier. They may have also worked as cooks, or even as drummers (e.g., Bill Yopp), but they were always the personal servant of a white soldier. Very often they attended explicitly under the patronage of a former master, or of a UCV camp. I’ve never seen a case where an African American man at a reunion who, during the war, was simply a hired cook, or teamster, or a member of a construction gang hired or conscripted from a planter, even though those latter groups must have been far more numerous. Those men either didn’t choose to attended reunions, or were not welcome to if they did.

So the dynamic here clearly has less to do with these black mens’ service, than with the personal relations between them as individuals, with individual white veterans. And they absolutely were presented and praised, for example in the pages of Confederate Veteran magazine, as embodying “old time” values of understanding their place and role relative to whites. They were praised (and paraded) as an endorsement of the Confederacy, and re-affirmation of the mutual bonds of affection between former slaves and former masters.

I don’t think we can say, in most cases, why these individuals chose to participate in this way. Most accounts don’t have any detailed quotes from these men, and those that do are usually filtered through organs like the Confederate Veteran, which are not likely to elicit fully candid responses from the men. But there are plenty of examples through American history were people push back against change they “should” embrace, opting to remain in a limited (but familiar) circumstance, rather than take real risk in stepping off into the unknown. Not everyone is bold, not everyone is brave in that way. In the Jim Crow South, which came to full maturity just around the time Confederate reunions became a common and popular thing, African Americans each had to find their own, individual path.

That’s what the Southron Heritage™ movement does. You should look sometime into how much time and effort gets put into justifying secession, 150 years later.

But yes, just as the African Americans at Confederate reunions were touted — very explicitly, unapologetically — as the embodiment of the “faithful slave,” so today we have these same men hailed as “black Confederate soldiers,” a designation that Robert E. Lee himself laughed at. It’s a very old narrative.

Sorry, Connie. I told you before, you’re done commenting here. Did you forget?

— AH

…but you haven’t given explanation of why the black man in the photograph doesn’t follow your stereotype.

Shouldn’t he be out front kneeling on one knee festooned with badges and turkey feathers? For everyone’s entertainment?

The fellow in the photo was probably a servant so why is he presented as a co-equal?

I would welcome more information on the man in the photo. There’s probably an interesting and worthwhile story there, although I’m not sure where to go from here to follow up.

But Alabama is your state, is it not? You may be better positioned to dig out the story. Let me know what you find out. 😉

Edited to add: Snark aside, the larger point of my post could have been made regarding most any photograph. While folks elsewhere are pondering is-he-or-isn’t-he-black, they’re ignoring the much larger, and more important question, about how African Americans were involved in Confederate reunions — what they got out of it, and what the Confederate veterans got out of their presence. Those are much harder questions, without easy answers, that advocates of BCS have studiously avoided, preferring instead to simply chalk up lists of photos and names, with little attempt to explore the stories behind them. That’s what I refer to in the title — “research a mile wide, and an inch deep.”

Many mid-level Confederate officers seemed not to have slave servants with them; but if they did have such slave servants, they were likely not only men of some social and/or economic substance in their home communities; those with such war-time army servants were likely more influential than equally ranked officers without them, during the war.

Thus after the late unpleasantness, such officers may have maintained their higher economic, social influential status at a Confederate Veterans encampment. If such high status veterans wanted their former slave servant that served faithfully with them honored at a re-union (yet in the context of knowing their ethnic “place”); I doubt lower economic, social status veterans would openly object. Likely many, but as likely, not all; such lower status Confederates, despite their status would see merit in these once slave servants that once had served faithfully; not in, but with, the Confederate army?

During the Depression, I think it was the Works Progress Administration that had whites interview former slaves about their experiences in the pre and post Civil War era. One would think at least one of those interviewed would have been a Confederate army slave servant, or widow, or child of one? Were any such Confederate slave servant narratives recorded?

I am a descendant of Capt. Edmund Bellinger, Sr., master of the “Blake” which brought the first cattle to South Carolina. He was a Surveyor-General, Attorney-General, Collector of Customs, and Judge in Admiralty of S.C., and “dissenter(?)”, who 1698 was created Landgrave of Tombodly and Ashepoo Baronies, S.C.

The wife or widow (Edmund Cussings Bellinger?) of a Civil War era Bellinger plantation and slave owner is mentioned in one of these WPA “slave narratives”. After the war, as per my memory of the narrative; she called the blacks one-by-one to the big house, telling them, they were free: and free to go, or free to stay. She opened the slave book and wrote out what in-effect were birth certificates for each, and where known, stating their parents names. She cautioned them to keep them for future use. I think this speaks well of these particular Bellingers.

I’m very proud of these black Bellingers: Pvt. Paris W. Bellinger, 103rd Regt. U.S. Colored Infantry, Co. F, died October 6, 1880, of malaria, Charleston, S.C., leaving a widow Clawaech Catherine Bellinger, and a child Francis Bellinger born 1874. He served February 23, 1865 to April 17, 1866. They married Hilton Head Island, June 1866. After the war, they lived 123 King St., Charleston. There was a black Sgt. Bellinger of Civil War, Hilton Head Island; but I’m missing his 4×5 card? He was a man of accomplishment. There is, or was, the Slave Relic Museum, Rev. Danny Drane, at 208 Carn St., Walterboro, S.C., 29488, http://slaverelics.org/, operated by a black; but I can’t find it’s data card either. Dr. Robert Bellinger, faculty and administration officer of the Museum of African American History, Suite 719, 14 Beacon St., Boston, Mass. 02109, may have more on both the black and white Bellingers? I remember the Walterboro Library, Local History Room, had a black Bellinger file.

That was a FWPA of December 18, 1936, Jacksonville, Florida, by Pearl Randolph of ex-slave Harriet Pinkney, born Sept. 25, 1790. Adeline her daughter born October 1, 1809, Betsy her daughter born Sept. 1, 1811. Belinda her daughter born Oct. 4, 1838. This record given my Mrs. Harriett Bellinger, her mistress; each slave received a similar one upon being freed.

About 20 years ago, my black Bellinger friend and genealogist, Mr. Lesley G. Bellinger, of Charlotte, N.C., retired V.P. of the old, good Wachovia Bank (in Old Salem, N.C., my grandmother born 1885, Miss Ruby Valerie Woollen, was Wachovia’s first female employe; an age 17 steno-typist for founder, Col. Fries) invited me to their five-day, Blackville, S.C., family re-union. It was wonderful. The family historians were Mrs. Alfado B. Hagood of Blackville, and (LtCol?) Joe Glover of Eielson AFB, Alaska. They descend freed slave Nancy Bellinger (of Aeolian Lawn plantation?) by children: Emily, Robert, Garfield, Clifford, and Elliott. Other possible children were Augusta, Lovick, and Peter? “Aeolian”, I think, means “Where the Wind Blows”? I think this Bellinger plantation is in Barnwell County, S.C., near St. Mathews? Nancy died Barnwell, S.C., in Blackville, age 77, born 1840, S.C., parents unknown; died June 17, 1917. I suspect the father of some, perhaps all, of Nancy’s children was the plantation “driver” who could have been either white or black?

I have this: Edmund Bellinger, slave, born Dec 6, 1838, of Harriet Gresham, of Charleston and Barnwell. Edmund Bellinger owner of Barnwell. Mother a seamstress, father a “driver”. She still corresponds with mistress in Barnwell, S.C. Through the distant fogs of the once evil of slavery; despite it, some good of black and white relationships, lessened that evil. I know this fits not, either the Professional Liberal view of human relationships in slavery, nor the Profession Conservative ideology either; that they were liberated from Darkest Africa with Christian ideology and singing in the fields. It seems to me that too many of the black rulers in Africa today, are as bad as the worst white rulers of Africa of yesteryear? Yes, not politically correct.

I think one of the Presidents Roosevelts mother was of Bellnger lineage, also?

Most of your post is informative and interesting as a personal opinion but when you state “I know this fits not, either the Professional Liberal view of human relationships in slavery” this is offensive to any intelligent reader and without merit or any bases in fact.

First, there is no such thing as a “professional Liberal” anything in this country. Also, this really implies that no other thinking group would find possible fault with the relationships you discus relative to slavery or that these other groups are unable to evaluate your statements in a content that is not favorable to your point – maybe, but a rather inclusive claim on your part that is not supported in any way by any facts in your post. Finally, unless you have some agenda that you haven’t supported, I am at a lost to why you find a need to make such an offensive statement.

Relative to slavery in the American South and the people who used and stole the labor of African Americans by way of a vast system of both State imposed terror and by way of their own use of force/torture/rape and other physical harms and/or threat in order to support an extremely vile and evil economic system – one that, by the way, they directly benefited immeasurably from – no minor acts of kindness by these ‘masters’ really matters relative to the terrible and vast injustices that these people directly inflicted upon another race.

That said, I see no reason not to add such acts in content as you did in your post but your need to attack anyone who might want to add their own content with know facts of what slavery really was regardless of trivial/minor acts of kindness, makes me believe you do not want these truths to be aired – maybe not but your offensive phrase still needs to be explained, then.

In any case what you added here with that pointless phrase is simply a baseless insult. You need to apologize and withdraw that offensive phrase from your otherwise interesting post.

For my part, I wish to apologize to Andy and others here for this long post on my part. The posts and articles here are always outstanding and interesting.

Dennis

I did not mean to imply there are not “professional conservatives”, also. As to whether such extreme views exist, or don’t exist; as well as moderate liberal and conservative views also; that is for each reader to decide, if they choose to.

I prefer not to defend the institution of slavery.

Decades ago, a fellow labor union friend and I where on a union “March on Washington” and between us were discussing slavery; I mentioned that in Guildford and Randolph Counties, North Carolina, that some Quakers owned slaves, and in many states some free blacks owned slaves. He denied such, and became hostile. While such was not widely practiced, and the reasons behind it differed from the usual reasons; those are the facts; like’m or not. You’r choice! I’m not offended either way.

My 3rd Great Uncles were in the 15th Alabama, two discharge on disability, two charged Little Round Top. Alabama also is known for having Creek Indians in some regiments, had a 3rd Great Uncle who was a Creek Indian in another regiment , not the 15th Alabama, my family in the 15th Regiment was half Waccawmaw Indian.

My Creek Indian Uncle

According to Stewart family history, Jackson LaFate Stewart fought in the Civil War. His enlistment date was August 14, 1862 and he entered as a Private. He served for the state of Florida (his home was very close to the AL/FL state line) and served for the Confederacy. He was wounded while fighting and left when the regiment moved on. He always thought they left him to die because he was Creek Indian and he was made to feel he wasn’t “worth” saving because of it.

Siddie Robinson found him injured in the woods and nursed him back to health.

After he recovered, they were married. His Civil War record lists him as “wounded on September 25, 1862” and “Never Returned”. He was dropped from the rolls on

January 1, 1863.

After the war when returning soldiers heard he had survived, Jackson was hunted as a deserter. He went into hiding in the swamps near his home and began using the name “JOHN L. STEWART”, rather than “Jackson”. The soldiers used hunting dogs to track him and they caught up with him on what is called “Jack’s Island”.

The story says that Jackson stood on an old tree stump and used his sword to slash at the dogs as they jumped up for him. He managed to escape and took his family from Alabama to live in Santa Rosa County, Florida for a while. They later returned to Baldwin County, AL; however, he continued to use his assumed name of “John” Until his death

My family in the 15th last name was Catrett , is their a list of names to go with the Reunion photo ??