Richard Quarls and the Dead Man’s Pension

Kevin recently highlighted a story done by a local news station in Florida on Richard Quarls, in honor of Black History Month. Quarls is one of the better-known “black Confederate soldiers,” and in 2003 had a Confederate headstone placed over his grave by the local SCV and UDC groups.

Kevin recently highlighted a story done by a local news station in Florida on Richard Quarls, in honor of Black History Month. Quarls is one of the better-known “black Confederate soldiers,” and in 2003 had a Confederate headstone placed over his grave by the local SCV and UDC groups.

In watching the video it occurred to me that, as presented, there are two narratives being told in the segment about Richard Quarls. One, as told by his great-granddaughter, Mary Crockett, is that of a slave who accompanied his master’s son to war. Ms. Crockett’s account, passed through her family, is clear about his status and role in the war, recounting that “when the master’s son got shot, and fell, [Quarls] picked up the gun, started firing the gun, and defending him while he laid on the ground.” The son is identified here as H. Middleton Quarles, who was killed in fighting at Maryland Gap, Maryland on September 13, 1862. It may have been in that action that Richard Quarls picked up Private Quarles’ rifle. There’s no reason to doubt Ms. Crockett’s account of her great-grandfather’s experience although, as always, family reminiscences are invariably subject to the vagaries of oral traditions passed from one generation to the next.

The second narrative is that overlaid by the SCV, which “discovered” Quarls’ military service and sponsored the headstone and memorial service. This second narrative is largely reflected in the dialogue of the news report, which is sprinkled with dramatic-sounding but vague phrases that blur the distinction between soldier and servant, slave and free. We are cautioned that “historians disagree about their numbers and how they served,” but also assured that “he may have been a servant and rifleman.” It’s suggested that he may have fought in thirty-three battles, and the viewer is told that at the end of the war Quarls was “honorably discharged.” It’s an impressive story to a general audience, but the historian immediately notices that there are very, very few specific facts presented that can be cross-checked against primary sources.

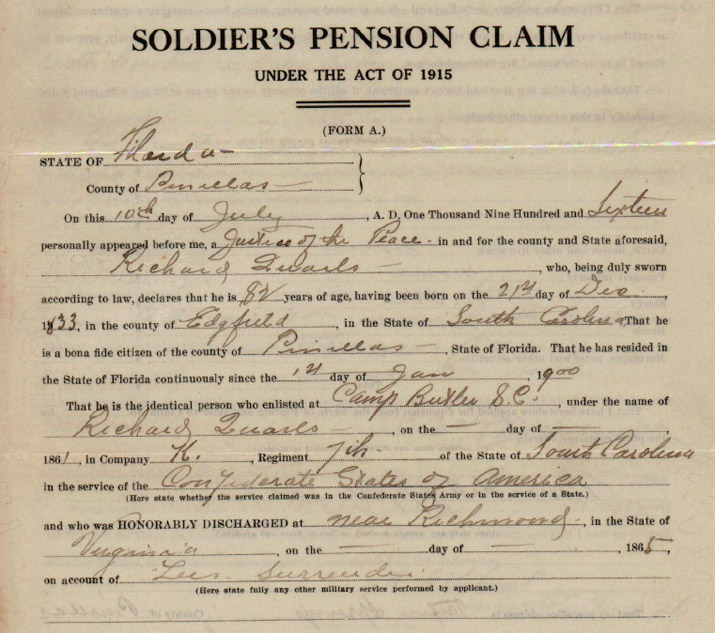

As noted in the video clip, the key element in identifying Quarls’ supposed service as a soldier is his pension record from the State of Florida (10MB PDF). The pitfalls of working with Confederate pension records have been discussed in detail elsewhere, and generally speaking, are less than fully-reliable in determining an individual’s status in 1861-65. They are particularly problematic on the case of Richard Quarls, and actually raise more questions about his wartime service than they answer.

Quarls applied for a pension in Pinellas County, Florida on July 10, 1916. On the first page of the application, he claims that he enlisted in Company K, 7th South Carolina Infantry, at Camp Butler, South Carolina, sometime in 1861. He gives his name upon enlistment as Richard Quarls. He claims to have been discharged in 1865 “near Richmond” Virginia, in 1865, on account of “Lee’s surrender.” The inference is that Quarls served almost the entire war with the 7th South Carolina Infantry. Quarl’s service claims were attested to by two witnesses, T. B. and O. W. Lanier. Both testified to have known Quarls during the war, affirmed his membership in the unit, and that they witnessed his full service as described in the application. These basic elements of his record during the war, claimed on the initial application, appear to have been accepted without question by the SCV, and form the wartime history of Richard Quarls that is now repeated as historic fact, his story being picked up by even non-Civil War authors, including Ann Coulter. (Coulter says Quarls’ grave was unmarked before the installation of the SCV’s stone, which is not true.) In fact, those self-same pension records cast serious doubt on much of what is “known” about Richard Quarls’ service during the Civil War.

Quarls’ initial pension application was dated July 10, 1916 (Page 6). The application was passed along by the state to the U.S. War Department for verification, which replied in mid-November that no one named “Richard Quarls” could be found either on the rolls of the 7th South Carolina, nor on the rolls “of any of S.C. C.S.A. Organizations” (Page 24). The letter did note, however, that a man named J. R. Quarles was listed as having enlisted in Co. K of the regiment. This J. R. Quarles, the letter noted, did not appear on regimental rolls after December 1861.

The local pension board passed this information along to Quarls in March 1917 (Page 25), with the additional information that neither of his two original affiants, T. B. and O. W. Lanier, could be witnesses to Quarls’ claimed service through the end of the war, as T. B. had been discharged in 1862 after the loss of an arm, and O. W. had been paroled at Greensboro, North Carolina in May 1865, apparently undermining Quarls’ claim to have been released near Richmond. The letter ended,

One of your witnesses is shown by the official records to have been discharged in 1862 on account of amputation of [his] arm. The other witness is shown to have been parolled at Greensboro at [the] Close of [the] War. Both your witnesses claim you were discharged near Richmond, while one of them was discharged in 1862, and the other at Greensboro. It will be necessary for you to show by affidavits of comrades who have personal knowledge of the facts that you were discharged at the close of the war. Also advise as to the name shown by record received from [the] War Department [i.e., J. R. Quarls] and to [the] reason your name is not shown on same. There are rolls of the Company and Regiment to May and June 1864, but your name is not shown on any of them; however, you claim to have enlisted in 1861.

There’s no record of how (or if) Quarls responded to the pension board’s challenge of the Laniers’ affidavits. But in July 1917 Quarls, or someone working on his behalf, obtained a notarized statement (Page 21) from one Wilson Farris, who swore

that he has known Richard Quarrels all his life — knew him while he was in the Confederate Army serving in the 7th South Carolina Regiment and knows him to be the same person whose name appears on the Muster Roll at Washington, DC as J. R. Quarrels [sic.].

Who Wilson Farris was is unknown; no one of that name appears on the rolls of the 7th South Carolina, so it’s not clear how he would have been in position to attest to Richard Quarls’ service through the war. Nonetheless, his sworn statement seems to have done the trick; it confirmed Quarls’ service and affirmed that he was, in fact, the J. R. Quarles located in the rolls at the War Department. Richard Quarls’ pension was approved on August 25, 1917 (Page 13), at the rate of $180 annually.

Quarls collected this pension until his death in 1925. His widow, Mary Quarls, continued to collect a widow’s pension for another twenty-six years until her own death in 1951.

But that pension had been awarded based on the applicant’s identification as J. R. Quarles. And that man had been dead and buried for half a century before Richard Quarls ever applied for a pension.

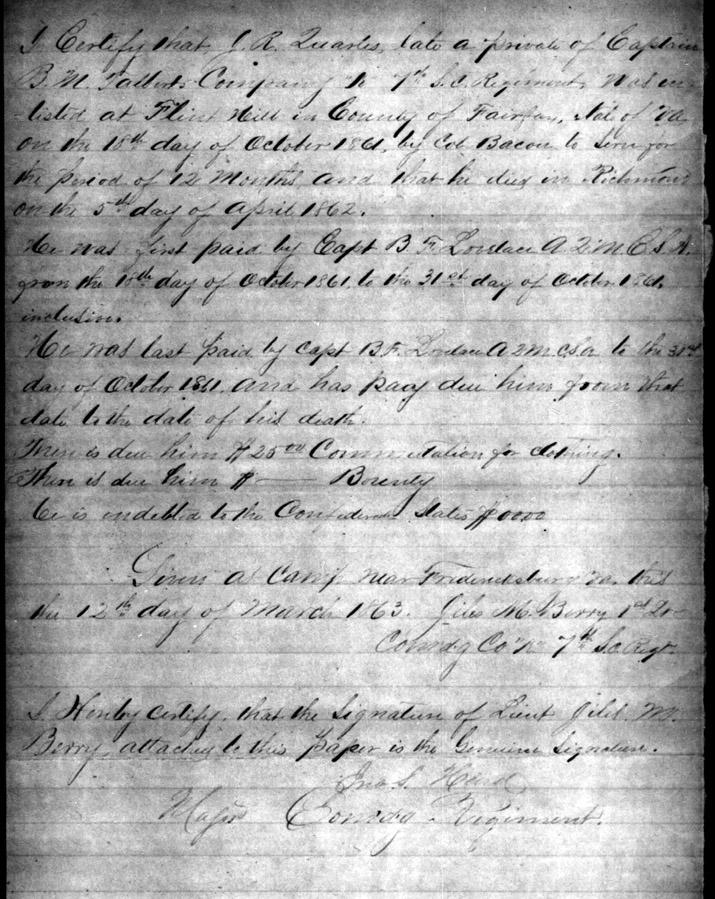

J. Richard Quarles enlisted in the 7th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry on October 5, 1861, for a 12-month term. J. Richard Quarles appears to have been the older brother of H. Middleton Quarles, Richard Quarls’ reported master. His service record (19MB PDF) shows he was admitted to Chimborazo Hospital No. 4 in Richmond on March 30, 1862, suffering from catarrh and pneumonia. His condition upon admission was noted as “feeble,” and that he had been sick in camp for two or three weeks previous. After lingering almost a week, Private Quarles died of pneumonia on April 5, 1862.

Memorandum certifying the death of Private J. Richard Quarles on April 5, 1862 at Richmond, signed by 1st Lt. Jiles M. Berry, commanding Co. K, and countersigned by Major John Stewart Hard, Commanding the 7th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry. The memorandum notes that Quarles was owed back pay from November 1, 1861 through the date of his death, along with a $25 commutation for clothing. Other documents in Quarles’ file note that these monies, totaling $81.83, were to be paid to his mother, Mary A. Fuller, of Edgefield, South Carolina. Via Footnote.

Recall that, in the November 1916 letter from the War Department that first mentioned J. R. Quarles in connection to Richard Quarls’ pension application, it was noted that there was no record of the former on regimental rolls after December 1861; this is because Private Quarles was never paid after that date, and he went into the hospital at the end of March 1862. It’s not clear why the War Department never snapped to the fact that J. R. Quarles died during the war.

Make no mistake: I do not believe that Richard Quarls intentionally misrepresented himself in obtaining a Confederate pension; I am not accusing either Richard or Mary Quarls of anything of that sort. I have no reason to believe Quarls intended to misrepresent himself in any way. Nor do I think he ended up getting something he didn’t deserve; in those days before Social Security or general disability pensions, if this pension allowed him and Mary some measure of financial security, that’s all to the good, and I’m glad of it.

But it’s easy to see how this might have happened. Quarls didn’t know how to read or write, or even to sign his own name; he must have relied on friends for assistance in this process — he was apparently well known and widely respected in Tarpon Springs — and it would be easy for a small miscommunication to have a profound difference. There were also at least five men named Quarles or Quarrells in the 7th South Carolina, futher compounding the confusion. I’ve seen no evidence, apart from Wilson Farris’ affidavit, that Richard Quarls ever used the initial J, nor a first name beginning with that letter. I believe that Richard Quarls was the beneficiary of a fortuitous misunderstanding, and a received a Confederate pension based on the military service of his former master’s older brother.

There is also little doubt that, in his later years, Quarls took some measure of pride in his Confederate association with the war, as evidenced by the reunion pin shown in his portraits, similar to this one. A user on Ancestry found the following obituary for Quarls in the Tarpon Springs Leader:

Columbus’s right name was Richard Quaws [sic.], the name of Christopher Columbus being assumed because of previous service that the man had in the Confederate Army under the name of Quaws, and which he thought would probably not meet with the approval of his friends here if they knew it. Nevertheless, his service with the Southern army was well known by all his colored acquaintances here, who thought of great deal of the old man. A few years ago he was taken to the convention of the Confederate Veterans in Washington by a number of veterans who attended from this city. Coming back, he was the proudest man in the colored quarters of the city, as he had seen the great President Wilson.

Columbus, or Quaws, was a slave on a Carolina plantation, at the beginning of the war between the North and South. He was very much attached to his master, and when he was called to the Southern colors, Quaws went, too, and served the duration of the conflict. Since that time he has been on the pension list, upon which he depended for his living, being too old to do anything for his own support. He lived in Tarpon Springs for the past twenty years, and was well known here among both white and colored, who thought a great deal of the old man. The funeral was held yesterday afternoon. His wife asks the Leader to thank all the white friends who have helped her and have sent flowers.

Just as today, in 1925 the distinctions between Quarls’ status as a slave and his agency in making his own, voluntary choices are blurred: “he was very much attached to his master, and when he was called to the Southern colors, Quaws went, too, and served the duration of the conflict.” (Mary Crockett was more explicit, saying “he was forced into the army. . . , so basically he didn’t have much choice but to fight.”) Whatever his actual beliefs or views it seems clear that, to many in the larger community, in his last years Quarls embodied the “faithful slave” meme so prevalent to the Lost Cause. That symbolism may bear some relation to the other unusual event in Quarls’ story. Ms. Crockett also told how, after his death, Quarls’ widow received a visit from the Ku Klux Klan, in their robes, who bowed before her and held a ceremony in honor of Quarls. The obituary also mentions this event, although doesn’t mention an in-person visit by robed Klansmen:

Yesterday afternoon, his wife was very much surprised to receive a letter bearing the seal of the Ku Klux Klan here from which dropped a check for twenty-five dollars when it was opened. The letter read: “Through sympathy for you and kind feelings toward your deceased husband, Christopher Columbus, this organization desires to extend to you their sympathy and help. We hand you herewith the sum of $25.00 to help defray the burial expenses of your deceased husband. Yours in sympathy, The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, Tarpon Springs.”

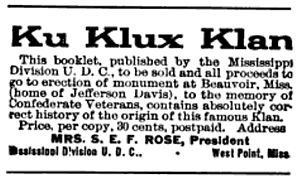

It is a complicated story, indeed. While modern Southron Heritage™ folks insist that there’s a bright line between themselves and groups like the Klan — epitomized by the ubiquitous mantra, “heritage, not hate” — it wasn’t always so. In the early years of the 20th century, at the time of what may be considered the Lost Cause high water mark, Confederate veterans’ groups often commemorated the original, Reconstruction-era Klan as a justified, even noble, continuation of the conflict of 1861-65 and published paeans to its memory. Membership in that earlier Klan was noted in old soldiers’ obituaries. The United Daughters of the Confederacy sold “absolutely correct” histories of the Klan (right) to raise funds to build a monument at Jefferson Davis’ home, Beauvior. The Confederate Veteran magazine cheered D. W. Griffiths’ infamous film Birth of a Nation, as having “done more in a few months’ time to arouse interest in that organization than all the articles written on the subject during the last forty years.” In short, at the very time Richard Quarls was applying for a Confederate pension and attending at least one Confederate reunion, the Reconstruction-era Klan was wholly embraced, lauded, and honored by Confederate veterans’ groups across the South. The memories of Confederate soldiers of 1861-65, and of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction, remained locked arm-in-arm for decades, well into the 20th century.

It is a complicated story, indeed. While modern Southron Heritage™ folks insist that there’s a bright line between themselves and groups like the Klan — epitomized by the ubiquitous mantra, “heritage, not hate” — it wasn’t always so. In the early years of the 20th century, at the time of what may be considered the Lost Cause high water mark, Confederate veterans’ groups often commemorated the original, Reconstruction-era Klan as a justified, even noble, continuation of the conflict of 1861-65 and published paeans to its memory. Membership in that earlier Klan was noted in old soldiers’ obituaries. The United Daughters of the Confederacy sold “absolutely correct” histories of the Klan (right) to raise funds to build a monument at Jefferson Davis’ home, Beauvior. The Confederate Veteran magazine cheered D. W. Griffiths’ infamous film Birth of a Nation, as having “done more in a few months’ time to arouse interest in that organization than all the articles written on the subject during the last forty years.” In short, at the very time Richard Quarls was applying for a Confederate pension and attending at least one Confederate reunion, the Reconstruction-era Klan was wholly embraced, lauded, and honored by Confederate veterans’ groups across the South. The memories of Confederate soldiers of 1861-65, and of the Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction, remained locked arm-in-arm for decades, well into the 20th century.

Why would Confederate veterans embrace Richard Quarls? My guess is that, for them, he embodied the core Lost Cause meme of the “faithful slave,” who remained true to the Confederate cause and his former master for decades after the war. We’ve seen this before, as with R. A. Gwynn (here and here), William Slaughter, Crock Davis, Bill Yopp and many others. That’s not to say that Quarls, Gwynne and the rest were compelled to participate, or didn’t take actual pride in their attendance at Confederate service — Quarls’ obituary is quite explicit about that — but it’s a mistake to assume that there weren’t larger, more subtle cultural and racial currents at work there. A when a new Klan (the so-called “Second KKK“) emerged after 1915, it’s entirely in keeping with their claims (however inaccurate) to be the revitalization of that earlier group that they would embrace a man that they viewed as representing the “correct” role and position of a former slave.

I’ve had the opportunity to dig into the histories of several men who’ve been identified as black Confederate soldiers. When contemporary records are available, the claims made often don’t hold up to close scrutiny. Upon further investigation some cases, like Thomas Tobe of South Carolina, confirm that the man in question served in a non-combatant role. Other examples, like that of James Kemp Holland, are patently wrong. In this case of Richard Quarls, it seems that we can be reasonably certain of several things, including:

- Quarls went to war as a slave, the body servant of a white soldier, possibly H. Middleton Quarles. He later claimed to have been in combat, picking up his master’s rifle when the latter was hit.

- In 1916, Quarls applied for a Confederate pension from the State of Florida. Florida appears not to have had a pension program for former servants, and Quarls applied using the form for former soldiers.

- In response to a query from the local pension board as to whether or not Quarls was the same man as J. R. Quarles, identified in the records, a man named Wilson Farris went to a notary and attested that Richard Quarls was, in fact, the same man.

- Having connected the pension applicant Richard Quarls with the service record of Private J. Richard Quarles, and unaware that Pvt. Quarles died in 1862, the State of Florida awarded Richard Quarls a Confederate Soldier’s pension.

- In his final years, Richard Quarls took a measure of pride in his Civil War experience, and attended a Confederate veterans’ reunion in Washington, D.C., likely the 1917 U.C.V. event.

Richard Quarls was the fortuitous beneficiary of some unknown clerical mix-up. But its effects have been far-reaching right down to today, almost a century after that error. As a result of that mistake, Richard Quarls’ pension records carry the name of Private J. Richard Quarles, a man who’d already been dead and buried for 50 years. Seventy-five years after Richard Quarls’ own death in Tarpon Springs, the local SCV and UDC camps latched onto those same pension records. In their rush to publicly identify Quarls as a black Confederate soldier, neither group, it seems, bothered pull a copy of the service record of Private J. Richard Quarles — the very man they assumed to be buried in Tarpon Springs — from the National Archives, which would have immediately revealed that the two men were different persons. (I realize that, with websites like Ancestry and Footnote, research of this sort is easier now than ten years ago. Nonetheless, the records were readily available.) As a result, today Richard Quarls today lies under a VA-provided headstone that lists a military rank he did not hold, and a first initial he never had.

Richard Quarls was the fortuitous beneficiary of some unknown clerical mix-up. But its effects have been far-reaching right down to today, almost a century after that error. As a result of that mistake, Richard Quarls’ pension records carry the name of Private J. Richard Quarles, a man who’d already been dead and buried for 50 years. Seventy-five years after Richard Quarls’ own death in Tarpon Springs, the local SCV and UDC camps latched onto those same pension records. In their rush to publicly identify Quarls as a black Confederate soldier, neither group, it seems, bothered pull a copy of the service record of Private J. Richard Quarles — the very man they assumed to be buried in Tarpon Springs — from the National Archives, which would have immediately revealed that the two men were different persons. (I realize that, with websites like Ancestry and Footnote, research of this sort is easier now than ten years ago. Nonetheless, the records were readily available.) As a result, today Richard Quarls today lies under a VA-provided headstone that lists a military rank he did not hold, and a first initial he never had.

It’s a complex story, the life of this man Richard Quarls, more complicated than even Mary Crockett probably imagines.

___________________________

Richard Quarls portrait via Fox News; headstone photo via Find-a-Grave.

Thanks again for another great piece of historical detective work.

Thanks. Richard Quarls’ case is a good example of how, when contemporary records are available, the BCS narrative doesn’t hold up well to close scrutiny. Quarls seems to have led a very interesting life, but it doesn’t do his memory any favors to misrepresent his experience.

I found it significant that, in the Fox News clip you posted, Mary Crockett seemed quite clear about her great-grandfather’s role and status; it was the SCV crowd that made the explicit claims about being a soldier. This one’s entirely on them.

You were absolutely right to characterize this as involving two separate narratives.

Excellent post, Andy. The situation with the headstone is of particular interest. It’s sad that it’s so easy for some folks to take advantage of the system and contribute to a waste of VA funds, especially when those funds are needed in other areas. Seems to me that it is no less than defrauding the government.

Robert, thanks. The headstone program has long been one of the SCV’s major projects that I thought was really doing a worthwhile thing. Unfortunately, that activity has also been co-opted by the drive to “prove” the existence of BCS, to the point where in Pulaski, Tennessee they actually set up a faux “cemetery” of them, all in one plot. (The VA refused to provide stones for that bit of foolishness.) Over time, of course, these misleading stones themselves become part of the “evidence” that these men were soldiers, so it becomes a self-reinforcing, closed loop. Epistemwhatsis closure, and all that.

It would be nice to have the SCV and UDC, that sponsored this business with Quarls, acknowledge the error and replace the stone with a correct name and no rank. (Leave it a CS stone, because that seems in keeping with Quarls’ views near the end of his life.) But I’m not holding my breath.

Yes, I’m quite familiar, as a former SCVer with the strong headstoning effort. I agree, they are attempting to abuse the system to make a point.

You point out that Quarles had a headstone prior to the VA stone. According to VA criteria, unless the original headstone is illegible or broken, a VA stone is not authorized. Of course, the point is moot anyway, considering they’ve given him someone else’s stone.

There are a number of cases here locally where, in the late 1990s, the SCV or SUV obtained stones for men whose graves were already marked, but carried no mention of their military service. Not sure how than came about. I know the VA changed its rules several years ago to restrict requests to those coming from actual family members, I presume to reduce the workload from third-party requests.

Sometimes, the sad part of such efforts results in the destruction of the older headstones, which are often finer in artistic displays than modern VA stones.

Andy, this is a terrific piece of work! The fraud and misuse of Quarls’ memory aside, I find a certain irony that this former slave has overshadowed, indeed displaced, the identity of a genuine white Confederate slaveholder. The real JR, wherever he might be, can’t be happy about this.

Marc, thanks. I have it on good authority that the ghost of J. Richard Quarles still wanders that cemetery, looking for his pension. Or braaaaiiinnnss, whatever.. 😉

Ann DeWitt take note, THIS is how history is done, not cutting and pasting snippets you don;t understand from the internet.

Andy, I hope you have this published.

Thanks. Unfortunately the majority of cases identified as BCS are based on long-postwar, second- or third-hand anecdotes or other “evidence” that can neither be verified nor refuted in the historical record, and the public is expected to implicitly trust the BCS narrative as accurate. When the material is available, though, that narrative often turns out to be simply wrong, and should rightly cast doubt on the “research” that goes into other cases, as well.

This was absolutely…..beautiful. I can’t even express how well this is presented and dictated as well as the research. Thank you for posting.

Thanks. It’s a down-in-the-weeds, convoluted story, and I wasn’t sure it would come across clearly.

Well, you’re just the guy we need for “down in the weeds” stories. You make a man – an honest-to-God, contradictory and complex man out of Quarls. It isn’t so much an act of debunking (although that has its place) as it is an act of honest remembrance you’ve engaged in…again.

For those who need Quarls to be a symbol of something less – well, in another era, I suspect you’d be challenged to a duel. My money’s on you in that event as well!

Very impressive…great work Andy.

Hello Andy,

Well researched. I applaud your objectivity in your reporting.

We must honor and respect the memories and recollections of the descendants of Richard Quarls. Sadly, they were set up as pawns in this disingenuous and convoluted story.

And J. R. Quarles must be walking around the grave really upset! lol

Peace & Blessings,

“Guided by the Ancestors”

In the South of my youth, when a “colored” person did something not usual for blacks, though not unusual for whites; often the term “colored” would be fixed after the blacks name; perhaps to help qualify the record,that though unusual, it was not a mistake. Not seeing that on the affidavit made me wonder, are two records being confused? I think you have made a good case that they have been; either intentionally or not.

Though all my Civil War ancestors were seven (white) Confederates and none where Union; none-the-less I admire and/or abhor those on both sides, Union and Confederate; depending on the circumstances. A kinsman on the Union side was Lt. Charles Dearborn Copp who one day in the circa 1880’s U.S. mail, received a (Congressional) Medal of Honor for his actions at the Battle of Fredericksburg where and when before the Confederate held “stone wall” and below famed Marye’s Heights, in the worst hand-to-hand combat in that battle; Copp picked up the fallen colors and railed the troops. I located Copp’s well-marked grave with nice civilian stone, but it made no mention of the Medal of Honor. I was aware where there was a good civilian stone, the VA did not supply a redundant one. However, since the civilian stone was deficient in mentioning the Medal of Honor, and Medal of Honor awardees were entitled to a Medal of Honor stone, Copp should receive one. I paid for the inscription on the obverse. The cemetery said they would instal the stone gratis. Copp’s stone can be found on the “Find a rave” website. I thought I was “breaking new ground” in the exception of a Medal of Honor veteran’s stone where there was a good civilian stone that did not “honor” he Medal of Honor. Later I was told it was not a new exception. I’ve even heard a veteran’s stone can now be supplied when there is still a good civilian stone; and I wonder if tat is accurate?

The Wilmington, N.C., Star-News last week had a front page story on how the State of North Carolina ntends to instal a State Roadside Historical Marker beside the Civil War era National Cemetery in Wilmington, ention the man black Union roops bried there.

Thanks for taking time to comment. There’s no question in my mind that the state pension board believed that Richard Quarls was the same man as identified by the War Department as J. R. Quarles; Quarls’ pension was approved within weeks of Farris’ affidavit saying so, apparently without further consultation with the War Department. That there’s nothing in Quarls’ application identifying him as African American may well have contributed to the confusion. As far as I can tell, Florida only authorized pensions for former veterans and their widows, with no separate pension program for former slaves/servants of soldiers, as Quarls definitely was, though (again) that’s not reflected in his application. At the same time as Quarls’ application in Florida, Mississippi did have a separate program explicitly for servants, such as this for Ephram Roberson from 1914.

That’s interesting about Lt. Copp’s headstone, we have a similar case here, with the grave of George Frank Robie — it was marked, but no indication of his award, so a new stone obtained.

The current protocol with the V.A. is confusing. As far as I know, the rule is still on the books that a V.A. marker is supplied only when there is no civilian marker. (The MoH exception makes sense, though.) Yet, I am seeing more and more graves marked with both, and in at least one instance, with two V.A. markers – one flat, one upright.

I hope this gets wide play, Andy. Nicely done!

Thanks.

…must have hit the wrong button, the above got posted before I finished corrections. con’t.

…mentioning the many Union black troops buried there. I believe the story also stated there are many black and white un-marked Union troops buried there also. There are many later wars interments also.

Perhaps twenty year ago, my dear black friend, Lesley G. Bellinger, of Charlotte, N.C., V.P. of the original Wachovia Bank (my grandmother, Miss Ruby Valerie Woollen, born 1885, age 17 was original Wachovia’s first female employee in Old Salem, a steno-typist for co-founder Col. Fries (Mr. Shaffner I think also helped start it?)) invited me to their week-long wonderful bi-annual (black) Bellinger family re-union in Blacksville, S.C. I am a descendant of Capt. Edmund Bellinger, Sr., Landgrave of Ashepoo and Tombodly Baronies, S.C. He was master of the “Blake” which brought the first cattle to, S.C. The black Bellinger re-union was wonderful. I tried not to participate as I was an invitee only, and not there by right of blood; and I did not consider it my place to be more than a privileged observer. The last afternoon they had a last lunch meeting with a “speak from your heart” talk. “Rich Uncle XXX” (from Chicago, I do not recall his name, but to me too; I addressed him as “Rich Uncle”. This was a family of early accomplishments, school “marms”, professional engineers, Air Force officers, a star basketball player in some Scandinavian country (uhh; and one young “gangster”).

Rich Uncle” at his turn, stood and said, more-or-less this: “The first day of the re-union, when one of the young males was meeting his fellow young cousins from away, the boy bragged he was wearing his “gang colors”. This bothered Rich Uncle, and he’d been wondering how to react? To that young Bellinger, Rich Uncle wanted to say this; when you are a (black) Bellinger, you are already in one of the best “gangs” the world as seen. Being a (black) Bellinger, you don’t need any other gangs. Your Bellinger gang is one that doesn’t hurt people, it helps people; both people in the gang, and people without. Wonder how the kid turned out?

The way I’d gotten to know “cousin” Lesley was I’d written Lesley, assuming he was “white”; as I’d heard he was from South Carolina. He was kind enough to write back that he too had extensive South Carolina Bellinger family data, but his was black.

Con’t

P.S. The incorrect spelling of Copp’s middle name is my error. There should be no “e” at the end of his name “Dearborn”.

Sorry to post this here, but I came across this blog while researching the Cousins/Cuzzens brothers mentioned here:

https://deadconfederates.wordpress.com/2010/08/22/now-were-finally-getting-somewhere/

Since the comments were closed, I was curious to see if anyone found out any further information about these brothers. These men are actually my great-great grand uncles and I have been doing some genealogy work. Since I am new to this, I haven’t had the easiest time finding information, but what I have found has been very interesting.

What I have confirmed so far:

From “The History of Watauga”, it has John (Franklin and W. Henry’s father) and Ellington Cousins described as “of dark skin” and “bringing white women with them”. That would make Franklin and William Henry mixed race. I can’t confirm if they were black or native american, or a combination, but I was always told we had Cherokee Indian in our ancestry (I can’t prove or disprove this). I recently spoke with a 97 year old cousin who was told indian as well as portuguese. I have never heard anything about any african-american ancestry, but being that it was the south, I wouldn’t be surprised if that fact was hidden due to racism. But knowing what I do know, I don’t think Franklin Cousins/Cuzzens can technically be counted as a “black confederate” that lost his life in battle being that he was of mixed race and it’s a possibility that he was a mix of white and native american.

One of the black Bellingers I’d cared about even before meeting “cousin” Lesley was Pvt. Paris W. Bellinger, 103rd Regt. U.S. Colored Infantry, Co. F. Died October 6, 1880 of malaria at Charleston, S.C. His wife was “Clawaech” (is this African or Arabic, if so, it’s meaning?) Catherine Bellinger. They married June 10th or 25th, 1866, Hilton Head Island, S.C., and lived 123 King Street, Charleston. They had one child under age 16 in 1891, named Francis Bellinger. He served between February 23, 1865, and April 17, 1866. Francis was born April or May 1874. Could someone in Charleston check on Pvt. Paris W. Bellinger’s grave and make sure it is properly marked, and if not, apply for a veteran’s stone?. On the obverse, they could inscribe his wife’s name and that of their son.

Likely his kinsman is Sgt. Theodore Bellinger of Co. “C”, 128th Colored Troops. His mother was Doll Bellinger of Walterboro, S.C., age 54 in 1866. She was he widow of Benjamin Bellinger who died the 5th of 1859. His sister was Sara P. Bellinger of both Walterboro and Charleston. Someone has donated black Bellinger records to the genealogy room of the Walterboro public library. I understand a black gentleman has a “Slave Museum” there, and it may be still on the internet? By-the-way; some defunct websites of value can be found in an archived websites website; it’s exact name I’ve forgotten. In 1999 I posted the now long defunct website: “Heirs of Hereditary Landgraves & Cassiques Society of South Carolina”. Search for that (use “quotation” marks) and it will take you to the archived websites. One of the “Landgraves” listed, is the mulatto Joseph Pendarvis, Esq., family. He’s there because he is frequently mistakenly listed as a Landgrave. He did own much land. In like vein is listed “fictional” Cassique (“created c1684″) Col. Edward Berkeley” of fictional “Kiawah” Barony. I now know about three more real barons. Corrections and additional names would be appreciated. Sgt. Theodore Bellinger died Gillonsville, S.C., February 6, 1866. If his grave is known, but not marked; please get him a veteran’s tombstone from “Uncle Sam”. He earned it. If Sgt. Bellinger’s remains are lost to he ages; please consider a memorial stone at Gillonsville , Walternoro or if a National Cemetery there, Chraleston?

Here I’d like to honor a wonderful white plantation mistress I came across in a 1936 Jacksonville, Florida, Federal Writer’s Project book by Peal Randolph. My notes are hard for me to decipher: if I recall correctly, Mrs. Harrlett Bellinger of a low country South Carolina plantation, kept the plantation’s slave book. Towards the end of the Civil War after the Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, Mrs. Bellinger called the freed slaves, one-by-one to the big house; and from the big book, gave each one what she called their birth certificate; explaining not to loose them, henceforth they would facilitate their lives as future, finally free, fellow Americans. Recalled long-later in Florida, the once slave: “Harriet Pinkney, born Sept. 25, 1790. Adeline, her daughter, born October 4, 1838. This record given to Harriet by Mrs. Harriett Bellinger, her mistress. Each slave received a similar one upon being freed. Edmund Bellinger, slave, born December 6, 1838, Harriet Gresham, Charleston, South Carolin. Edward Bellinger owner of Barnwell, S.C. Mother a seamstress, father a “driver” (this could be white or black as they were both kinds. Sometimes white drivers were kinder than black drivers. She wed Gaylord Jeannette, Co. “T”, 35th Regt.; lived at 1305 West 31st, Jacksonville, Florida., with granddaughter and second husband. Still corresponded with mistress in Barnwell, South Carolina.

Landgrave Capt. Edmund Bellinger, Sr., was “created 1698”; he sat as a Judge in Admiralty and Surveyor-General of South Carolina. His wife was Sarah Elizabeth Cartwright. Landgrave Edmund Bellinger, Jr., inherited circa 1705. Sir Edmund Bellinger, III, inherited circa 1739. Edmund Bellinger, IV, inherited 1772 ( American nobility was proscribed by the U.S. Constitution). Joseph Bellinger was he last Bellinger Landgrave, 1773.

I descend Edmund Sr’s son, Capt. William Bellinger, Sr., who may have been both a militia captain and ship’s master, who may have had a Caribbean-style home on the Beaufort, North Carolina (not South Carolina) waterfront street? He wed Mary Cantey, daughter of William and Jane Baker Cantey (her parents Richard and Elizabeth Baker were of English nobility, allegedly). His parents were Teige and Elizabeth Cantey who arrived Charleston 1672 from Barbados (source of origin of some Cantey slaves?). Mrs. Mary Cantey Bellinger had Elizabeth Bellinger (some say this is correct, others incorrect), the second wife of Loyalist, the Hon. Henry Yonge, Sr., H. M. Surveyor-General of Georgia. His summer home, “Orangedale”, Skidaway Island; is now the site of “The Landings” is, where that lady sleeping in her daughter’s kitchen was stalked by a large alligator recently that passed through the screen door, pulling her a distance into the lake where it consumed part of her. The alligator was killed, and part of the human remains found within. Henry called his first wife, Mrs. Christiana Bulloch Yonge a “rebel”, she being the sister of Patriot Gov. Archibald Bullock of Georgia, President Teddy Roosevelt’s mother’s forebear. Henry had my Capt. Philip Yonge, Loyalist, H. M. Surveyor-General of Georgia, who wed Christian Mackenzie; daughter of Capt. Wm. Mackenzie, H.M. Comptroller and Collector of Customs, Sunbury, Georgia. He had a son John who’s wife was Christina. Daughter Anna Jean Mackenzie wed John Simpson, Jr., of Sabine’s Fields (part of now industrial Savannah)(brother of James Simpson), Chief Justice, Member of H. M. Council, Crown Clerk of Court, who died 1784. His father was Chief Justice John Simpson, Sr.

Henry Yonge, Sr’s son Maj. Henry Yonge, Jr., Loyalist, at St. Augustine, Florida, commanded a company of Menorcans, at St. Augustine with Philip. Henry Jr. was H.M. Attorney-General of British East Florida, who as such; annulled the indentures of 1,000 wrongfully enslaved, New Smyrna Beach, Florida, Menorcans. His plantation is now the town of Ormond, Florida; it’s public library on Yonge Street. Henry Sr’s father was the Hon. Francis Yonge, Lord Proprietors Surveyor-General of the Bahamas, Carolinas, and Georgia. Sometimes understanding the white families; who inherited from who; helps sort out their slave’s lineages too.

Let’s keep this focused on Richard Quarls.

Honest question- do you think there might me any other documentation on the actual Richard Quarls? Please don’t take that as an affront on your efforts, as I recognize how much paperwork you must have looked through for this excellent analysis. But as someone who is not a professional historian, I do wonder how much of stories like this are lost because the South did not think it worthwhile to keep records of blacks, especially slaves, like they did with whites. Is there actually no exception to the rule regarding black Confederates or have we just not found it because slaves were not deemed worthy of a place in record-keeping?

Honest question, honest answer — I’m sure there’s a good bit of material available that would help fill out Quarls’ life story a bit more. The Internet is a fantastic tool, but there’s a real limit to what one can do at a distance, and a full work-up would really require boots-on-the-ground in Florida. (Fortunately some of this material is available through Ancestry.com, which was a big help.)

My focus in this case was narrow, not to compile a biography of Richard Quarls per se, but to look at the evidence used in putting up the headstone and identifying him as a BCS. As far as I can tell, that rests entirely on the claim made in the 1916 pension application, which paperwork “confirmed” that he was the J. R. Quarles that appears on the 7th South Carolina rolls. What’s somewhat staggering is that the SCV either didn’t obtain a copy of that soldier’s service record — that is to say, the man they believed was buried in that plot — or obtained it and then willfully ignored the fact that the guy died in 1862. (The record goes on for multiple pages on this; it’s not a one-off notation.) The upshot of this is that Richard Quarls now lies under a VA headstone that carries another man’s name and rank.

There may be other, primary source documents that shed further light on this, but the critical documents in this case (Richard Quarls’ pension application and J. R. Quarles’ service record) are readily available online, and I’ve also set them up for direct download. Folks are welcome to check my work, and contribute additional, relevant primary source documentation.

I do believe that there were a very small number — dozens, not hundreds or thousands — of African American men who, through particular skill or personal patronage by white officers, achieved something close to status as a soldier, under arms, though it would necessarily be unofficial. (Holt Collier is a likely example of this.) But the vast majority of what’s offered as “evidence” of BCS either cannot be corroborated, or (as in the case of Richard Quarls) doesn’t hold up to close scrutiny. Sometimes, as in the case of the infamous “Louisiana Native Guard” photo, it’s a deliberate fabrication.

Contrary to what some believe, my intent here is not to prove that BCS never existed; it’s to push those who advocate for them to approach the subject like an historian, and do due diligence on their claims. Real BCS are the proverbial needle in a haystack; it’s hard to find that needle when groups like the SCV insist on continually throwing fistfuls of hay in your face by making wild and often wholly unsubstantiated claims.

I should add that tracing former slaves’ history prior to the 1870 U.S. Census is pretty difficult. In the 1860 census and previous, they were not listed by name — only sex, skin color (“black,” “mulatto,” etc.) and approximate age. Unless there’s a reference in some archived private papers, there’s very little out there, and often nothing at all that can be found online.

This absence of primary source material is part of what leads to claims for BCS, and what makes them impossible to corroborate. The claims for an individual having been a BCS are often based on family anecdotes that may or may not be passed down accurately, and often with subtle but unknown alteration over the decades. But they cannot be corroborated in other sources, and there’s no way to know how accurate they are.

The Wilmington (N.C.) Star-News, perhaps two years ago, carried a story on a local “Medal of Honor” awardee tombstone (I think that was the alleged military honor) that was (ordered?) removed because it was inaccurate. I think it was a privately funded, not government funded stone; but never-the-less inaccurate. There may be legislation about inaccurate if not deceptive claims to the Medal of Honor. I’ve read of lesser inaccuracies of government provided stones that were none-the-less either revoked or corrected. As this might be a major inaccuracy; and especially because it is a governmentally provided stone; it should be accurate for the sake of both men. And our fellow American, once slave, should have his accurate stone too, even if not provided per U.S. law.

I don’t expect the SCV to acknowledge the inaccuracies on Mr. Quarls’ stone. They had ready access a decade ago (by mail) to the same documents I’ve used here, and either overlooked or ignored them. It seems naive to think that they’d admit an error at this point.

I’m not aware of any case, out of the dozens of men the SCV has publicly declared to be BCS, where they’re formally retracted such a claim, regardless of the evidence offered to refute it. The overarching goal of the group isn’t to tell these specific mens’ stories in all their complex detail, but to depict them as examples of a larger meme, that of the black Confederate soldier. They’ve gone all in on this effort, even to the point of creating a faux cemetery for them in Pulaski, Tennessee. Why Pulaski, of all places? Let’s just say they’re really, really motivated to change that community’s historical narrative when it comes to race and the legacy of the war.

[…] such. Basically, the sort of stuff Andy Hall has been doing, and with good effect I might add, with web based sources. Ended up with a two inch thick folder in my files on a couple dozen “black […]

Andy:

This is an interesting story and I think can provide you with an equally intriguing postscript.

I am finishing a book on the 7th South Carolina Volunteers for Broadfoot Publishing. I have done some extensive research both for the narrative and the biographical roster that accompanies it.

Colonel David Wyatt Aiken commanded the 7th at Maryland Heights where Hugh Middleton Quarles (Richard’s master) fell. Aiken wrote a very detailed account of this action which included details of Quarles’ death. The regiment had been ordered to assault a Federal position along the ridge of Maryland Heights and ran into trouble when they encountered a tangle of felled trees. Unable to move forward, Aiken ordered everyone to lay down and take cover. Below is an excerpt from my book:

“Color Sergeant Charles M. Burress would not lay down with the regiment, as he probably thought it was his duty to remain standing with the flag. Aiken shouted for the man to get down, then approached the sergeant and ordered him down. Before Burress could obey, a bullet struck him in the abdomen, and he fell mortally wounded. Private Belton O. Adams caught the flag staff as it fell, stood, and raised the colors over his head, and was also hit with a mortal wound. Before the colors hit the ground, Private Hugh Middleton Quarles snatched them up and whirled them defiantly over his head. He fell dead when a bullet slammed into his heart. Only one other man of the color guard remained unhurt, so Aiken left the flag where it lay, “a temporary winding sheet for poor Quarles.”

Aiken makes no mention of Quarles’ slave picking up his rifle etc.

However, I came across an astounding newspaper article dated a few months after the battle. The writer was a northern correspondent who visited Harper’s Ferry and had been given a tour of Maryland Heights. He describes the field of felled trees in front of the Union fortifications, and even noted several Confederate burials among the fallen timber, including Hugh Middleton Quarles.

The 3rd Maryland (Potomac Home Brigade) defended part of the line for the Federal’s on Maryland Heights that day.

He relates this account of the battle:

“Do you see that narrow opening – a fat man could not pass it – in the old breastwork? In the fight of Saturday morning, Col. Graffin posted a man there, and he was immediately shot down; another and another, and yet another, shared their comrade’s fate. Lieut-Col. Downey of the 3d Maryland passes the fatal gap, and is badly wounded; Col Graffin crosses it, at quick step, to draw the sharpshooter’s fire, and mark his hiding-place, and his breast is grazed! Then Capt. Fallon of the 3d Maryland crawls into the thicket, and from behind a log brings down the fellow with the Wesson rifle. It is a negro.” (New York Herald Tribune, 20 November, 1862, p. 8).

So according to this Northern account, at least one black man wielded a weapon for the Rebel cause. The article suggests that the black man was killed so it obviously could not be Richard Quarles. It should be pointed out that the 7th was just one regiment in Kershaw’s South Carolina Brigade. This black man could have been attached to the 3rd South Carolina (which charged over the prostrate 7th) or the 2nd or 8th South Carolina who were also present.

This account does not validate Quarles’ or the SCV claims in any way, but does offer at least some evidence that there is a chance that Quarles may indeed have picked up a weapon that day.

Glen:

Thanks so much for this. The claim that Richard Quarls used a weapon is not one I especially dispute, as there are many anecdotal examples of that happening. It’s how that gets spun off into other claims.

Can I post this in the regular blog as a follow-up to the earlier story?

Absolutely – thanks Andy

Excellent!