“Mr. Holland of Grimes”

Update, October 15, 2011: In the comments, Lynna Kay Shuffield provides an update on the death of Holland’s first wife, Samuella, and two of their children in October 1865. This profile has been updated to reflect that new information, as indicated in blue text — thanks!

If you type James Kemp Holland’s name into a search engine, you’ll quickly discover that he “became the highest ranking black, rising to the rank of Colonel and served on the staff of Governor Pendleton Murrah of Texas.” This story has been picked up a number of places, including on H. K. Edgerton’s SouthernHeritage411 website.

Except that Colonel Holland wasn’t black, or of mixed race. James Kemp Holland is a case study of how well-intentioned but lax research can go very, very wrong.

James Kemp Holland (left, in later life) was born in 1822 in Tennessee. His family emigrated to the Republic of Texas in 1842 and settled in east Texas, what is now Panola County. In fact, family tradition holds that James Kemp Holland’s father, Spearman Holland, named Panola County, using a Native American word of cotton. The extended Holland family were planters, with large holdings in land and slaves.

James Kemp Holland (left, in later life) was born in 1822 in Tennessee. His family emigrated to the Republic of Texas in 1842 and settled in east Texas, what is now Panola County. In fact, family tradition holds that James Kemp Holland’s father, Spearman Holland, named Panola County, using a Native American word of cotton. The extended Holland family were planters, with large holdings in land and slaves.

Spearman Holland (1802-1872) was heavily involved in local and state politics. He was serving in the Texas Legislature when the Mexican War began, and returned to East Texas from Austin with orders from the governor to raise a raise a company of mounted rangers. James Kemp Holland, at 24, was deemed too young to command the company, so his uncle Bird Holland was appointed captain. James Kemp Holland was subsequently elected lieutenant “by acclamation.”

At the opening of the Battle of Monterrey, Holland’s company was assigned to accompany a battery of the U.S. 3rd Artillery, commanded by Captain Braxton Bragg, positioned opposite the city’s main gate. When the Mexicans fell back, the Texans moved into the city proper where the fighting became close and heated:

Captain Bird Holland, having become disabled, it was here that Lieutenant Holland won his spurs when he made his dash into the city, gallantly leading the Second battalion of the Second Texas Mounted Volunteers under a galling fire from the Old Moor Fort and all the guns along the city’s fortification. Upon dismounting and scaling the walls of the city, the Seventeenth Rangers were again thrown with Captain Bragg on one of the main thoroughfares. And now the Battle of House-tops began, and from every roof and cross street came leaden hail.

The rangers were driven within, where they fought through the houses and walls. Later upon the house-tops the fight went bravely on, the Mexican soldiers disputing every inch of ground.

While this was going on, Bragg was sweeping the streets, and General Ampudia, who was present with the flower of the army, was driven pell mell towards the main plaza, where they intended making a last stand, but with a “little more grape” from Captain Bragg the white flag soon went up.

During the house to house and hand to hand conflict. Lieutenant Holland saw that across the street Texas Rangers were firing from the lower door and windows at the retreating Mexicans down the street, and Mexican soldiers on the top of the parapetted roofs of the same houses, were firing back at the Texans, neither knowing of the proximity of the other!

House-to-house fighting during the Battle of Monterrey. Library of Congress.

Lieutenant Holland’s uncle, U.S. Commissary Captain Kemp S. Holland, later died in camp before the Battle of Buena Vista, and Lieutenant Holland was assigned to bring his body back to Texas for burial. This appears to be the end of James Kemp Holland’s military experience until sometime during the Civil War.

James Kemp Holland soon followed his father into politics, serving in the Texas House of Representatives in the Third Legislature (November 1849 to December 1850). He was appointed U.S. Marshal for Eastern Texas in 1851, but successfully ran for state senator and served in the Fifth Legislature (November 1853 to February 1854). Sometime after that he relocated to Grimes County, northwest of Houston. He returned to the Texas House in late 1861, where he served alongside his father, who was referred to in the House Journal as “Mr. Holland of Panola,” while James Kemp Holland was known as “Mr. Holland of Grimes.”

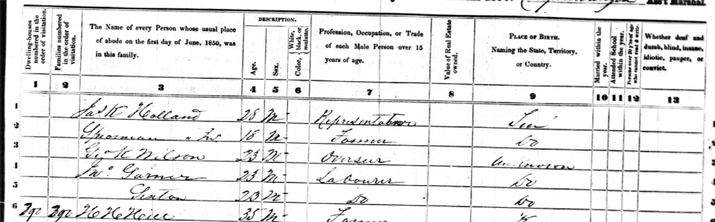

James Kemp Holland in the 1850 U.S. Census for Panola County. His occupation is listed as “Representative.”

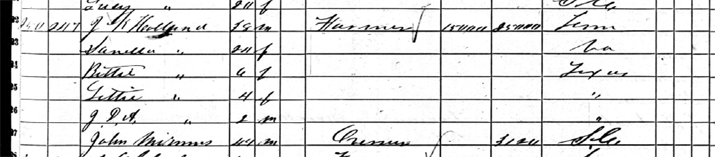

In early 1854 James Kemp Holland married Samuella Andrews in Houston. At this time James Kemp Holland was thirty-two, and Samuella about eighteen. By the time of the 1860 census, James Kemp and Samuella Holland had three children — Bettie, age 6, Lilly, age 4, and a son, J. D. A. Holland, age 2.

Holland’s property (lower left) just before the Civil War, located just northeast of present-day Navasota, along the Brazos River. The county seat, Anderson, appears at upper right. Texas General Land Office.

At the time of the 1860 census, Holland was a wealthy planter along the western border of Grimes County, just northeast of present-day Navasota. The census that year valued his land holdings at $15,000, and his personal property at $25,000. Holland does not appear in that year’s slave schedules, although $25,000 in that time and place would usually indicate property in slaves.

Holland in the 1860 U.S. Census for Grimes County.

During the early part of the Civil War, James Kemp Holland served in the Texas House of Representatives. He reportedly declined a nomination to the Texas Secession Convention, but was elected to serve in the the Ninth Legislature, November 1861 to March 1863. In 1863 he was appointed aide-de-camp to Governor Pendleton Murrah (left). A letter survives from the spring of 1864 in which the governor, writing to the Confederate general commanding the District of Texas, introduces Colonel Holland and asks that he not be interfered with in his travels around the state:

During the early part of the Civil War, James Kemp Holland served in the Texas House of Representatives. He reportedly declined a nomination to the Texas Secession Convention, but was elected to serve in the the Ninth Legislature, November 1861 to March 1863. In 1863 he was appointed aide-de-camp to Governor Pendleton Murrah (left). A letter survives from the spring of 1864 in which the governor, writing to the Confederate general commanding the District of Texas, introduces Colonel Holland and asks that he not be interfered with in his travels around the state:

Executive Department

Austin 13th April 1864Maj Genl

J. B. Magruder

Sir:Col. J. K. Holland is aid de camp to the executive of Texas appointed and commissioned by authority of her Laws — I need his services and [ask] that he may not be annoyed in his movements — you will do me a favor by endorsing this statement [and issuing] an order — that he shall not be interfered with by any military officers & that his commission shall be respected by those under your command. He is a planter of Grimes County.

I have the honor to be

Your Obt Svt,

P. Murrah

Governor Murrah’s letter of introduction for Col. Holland. Footnote.com

Based on the letter, it seems likely that Colonel Holland served at the governor’s liaison for military affairs around the state. Murrah was not in good health — he died in Mexico of tuberculosis shortly after the end of the war — and may not have traveled as much as a healthier man might be able to.

Early mention of Holland’s title of “colonel,” Texas State Gazette, April 4, 1854.

It’s not clear what sort of formal commission Holland held as colonel, apart from Governor Murrah’s assertion that it was “by authority of her Laws.” He almost certainly didn’t “rise” to the rank of colonel in any conventional sense; he undoubtedly was appointed at that rank. It’s also worth mentioning that, while his only previous known military experience was as a very junior officer in the Mexican War, he was already being addressed as “Colonel James K. Holland” a full decade before Murrah’s letter, when the Texas State Gazette used the title in announcing his marriage to Samuella Andrews. It was a tradition of sorts in Texas and across the South in the 19th century to address prominent men with a military background — almost any military background — by an inflated military title. It was such a common practice that it was even joked about, as when one old Hood’s Brigade veteran composed a ditty,

It’s General That and Colonel This

And Captain So and So.

There’s not a private in the list

No matter where you go.

After the war, James Kemp Holland returned Grimes County. There, Holland soon suffered great personal tragedy, the deaths of his wife Samuella and two of their young children John D. A. Holland, age 7, and Nannie Hicks Holland, age 5. The Houston Telegraph carried the following obituary on October 18, 1865:

DIED – At Farmingdale, Grimes county, on the 2nd October, John D. A., and Nannie Hicks, only son and youngest daughter of Col J. K. and Samuella Holland. They died almost at the same moment of Congestion, and on the 5th instant, Mrs. Samuella Holland, after forty-one days of suffering – disease, Gastro Interetis.

“Leaves have their time to fall,

And flowers to wither in the night-wind’s breath;

But all – thou hast all

Seasons for thine own! O, Death!”The fairest picture of happiness on earth, “the only bliss that has survived the fall,” is an unbroken family household, where love and peace and harmony reign. Such was this domestic circle until the angle Death came and bore away one half of its number to their heavenly home.

Mrs. Holland was the daughter of Col L. D. and Eugenia Andrews, of this city, and one of the loveliest daughters of Texas; as pure and excellent in character, as she was fair and beautiful in person. She was a true woman, having all those feminine qualities which call forth admiration and affection from all classes. Although possessing intellectual culture, and those accomplishments which adorn society, the pomp and pleasure of life had no adornments for her. Her only happiness was in her home, where she was enshrined the idol of an adoring husband – the guide and companion of her children, and all that was perfect in the eyes of her faithful and devoted servants.

She had long been a conscientious Christian, and when our Heavenly Father called her she was ready, and the stream of her life passed away calmly and peacefully into the great ocean of eternity.

“So beautiful, she well might grace,

The bowers where angles dwell;

And waft their fragrance to His throne

Who “doeth all things well.”

Though he had served as an aide to Confederate Governor Murrah — and his uncle Bird Holland had been killed in action leading his Confederate regiment during the war — James Kemp Holland appears to have been committed to the smooth reunification of North and South, and a supporter of President Andrew Johnson’s relatively lenient Reconstruction policies. Along with Andrew Jackson Hamilton (left), a prewar U.S. Representative from Texas and the state’s first military governor under Reconstruction, Holland was a delegate representing Texas at the National Union Convention (also known as the Southern Loyalist Convention) in Philadelphia in August 1866.

Though he had served as an aide to Confederate Governor Murrah — and his uncle Bird Holland had been killed in action leading his Confederate regiment during the war — James Kemp Holland appears to have been committed to the smooth reunification of North and South, and a supporter of President Andrew Johnson’s relatively lenient Reconstruction policies. Along with Andrew Jackson Hamilton (left), a prewar U.S. Representative from Texas and the state’s first military governor under Reconstruction, Holland was a delegate representing Texas at the National Union Convention (also known as the Southern Loyalist Convention) in Philadelphia in August 1866.

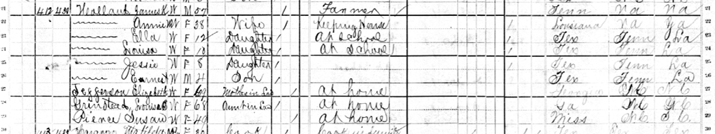

Around 1867 he married Annie W. Jefferson, and together they had four children — daughters Ella, Louise, and Jessie, and one son, Earnest. In the 1870 U.S. Census, Holland’s property was valued at $1,800, and his personal property at $1,100. Unusually, his daughters from his first marriage, Betty and Lilly, ages 13 and 12 respectively, are each listed as holding $9,000 in real estate. Presumably this was being held in trust for them by their father.

The Holland family in the 1870 U.S. Census.

By 1880, Holland and his family had moved one county over, to Washington County, where they’d settled at Chappel Hill. It was a large household; in addition to Annie and four children, Annie’s mother and the mother’s sister were living with James Kemp Holland, along with another middle-aged widow, Susan Pierce, of unknown relationship to the family.

Holland and his family, residing in Chappel Hill, Washington County, in the 1880 U.S. Census.

In his later years, James Kemp Holland worked as a real estate agent in Austin, both on his own and with partners. He died after a carriage accident in 1898 in Tehuacana, Texas, east of Waco in Limestone County.

Obviously the foregoing is not a full-length biography of James Kemp Holland, nor does it represent exhaustive research incorporating all possible sources. But nowhere in the primary source materials available did I find anything that indicated James Kemp Holland was black, or of mixed race.

There are four available census rolls for Holland, spanning 1850 to 1880. (The 1890 U.S. Census was destroyed in a fire.) Of those four, none designate him black or “mulatto.” The 1850 censuses uses a tick mark ( – ) that continues uninterrupted for page after page of the enumeration, apparently as a sort of “ditto;” the 1860 census carries no notation for anyone for several pages; the 1870 and 1880 censuses explicitly designate each member of the Holland household as white.

None of the mentions I found of James Kemp Holland in a variety of sources published during his lifetime or soon after his death carried any suggestion that he was of mixed race or black. I saw no instance of “colored” or “mulatto” or “Negro” appended to his name in newspaper articles, directories, or official documents like the Texas House Journal, compiled and printed at a time when such notations were almost universal. There’s no mention of it in any biographical sketch I’ve seen, such as that published in the print edition of the Handbook of Texas.

Nor, frankly, is it especially plausible that a black or mixed-race man could hold a series of high elected and appointed offices in a state as virulently white supremacist as antebellum Texas. Free persons of color were an extreme rarity in Texas. Their presence was actually outlawed in the republic at the time the Hollands immigrated to Texas, and they were prohibited from owning land; there was a famous case in which a free black who had aided the Texas Revolution required — literally — an act of Congress to retain title to the land grant he’d been awarded for his services. Even after statehood, laws restricting the activities and rights of free persons of color were among the most repressive in the South. The free population of black and mixed-race persons in antebellum Texas was vanishingly small, and shrinking: 397 in 1850, and just 355 a decade later. (There were more than ten times that number of free colored persons in 1860 in Charleston County, South Carolina, alone.) During that same period, the slave population exploded, from 58,161 to 182,566, an increase of more than 200%. The free black population of Panola (1850) and Grimes (1860) Counties, where James Kemp Holland lived at the time of those censuses, were 2 and 1, respectively.

In short, the only place I find even a suggestion that James Kemp Holland was black or of mixed race is online, when he’s identified as a “black Confederate.” It is neither evidenced in primary sources, nor plausible in the context of the time and place.

Where did the notion come from that James Kemp Holland was black, or of mixed race? I’m not certain, but there are two possible sources I’ve found that may be the source of confusion.

The first is this webpage on the early history of the black community in Panola County. The page — and several others that repeat the same information — goes into considerable detail on the Holland family, including James Kemp Holland, because they were among the first large-scale planters in the area and their bondsmen formed the initial black community there, Holland Quarters. It doesn’t make the claim that James Kemp Holland was black, or of mixed race, but the page is such a poorly-organized mishmash of history, genealogy and commentary that it’s easy to be confused. A casual read of the page could easily lead one to believe that James Kemp Holland was himself a man of color.

The second possible source is the famous Handbook of Texas, the standard, quick-reference guide to the region’s history. Both the online and final print versions of the Handbook include biographies of Bird Holland that mention that he fathered three sons by a slave woman, one of whom was named James. It seems possible that this James Holland was confused for his first cousin, James Kemp Holland, leading one to believe that the latter was a man of mixed race.

Using either of these resources, it would be easy to get the impression that James Kemp Holland was black, or of mixed race. But — and this is important — it’s equally easy to correct. Even a little digging in readily-available, online sources would cast doubt on that notion of James Kemp Holland’s race. But as so often happens with men identified as “black Confederates,” it would seem that little other digging was done to actually establish much at all about his life or career.

It’s all very sloppy, and very misleading. It doesn’t have to be this way, and shouldn’t. A little due diligence, a little more digging, would have completely avoided this misrepresentation.

___________________________________

James Kemp Holland portrait from the Texas House Journal of the Ninth Legislature, First Called Session. Pendleton Murrah portrait from the Texas State Preservation Board.

At the time of the 1860 census, Holland was a wealthy planter along the western border of Grimes County, just northeast of present-day Navasota. The census that year valued his land holdings at $15,000, and his personal property at $25,000.

This established fact seems completely incongruous with the notion that Holland was black. I’m sure the 1860 census shows vanishingly small odds of a free black man having $40,000 net worth. It there a 1860 census DB somewhere, with location, race & wealth? If data is available, it shouldn’t be a hard test.

You can generate summary tables here — the interface is a little clunky:

http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/

But I don’t know of any database that would allow the user to run comparisons like you’re suggesting. It would be immensely useful if it could be done.

In Holland’s specific case, in Grimes County in 1860 the census recorded one free person of color. Not one family, one individual. I suspect that’s why the 1850 and 1860 census enumerators didn’t bother to record “W” in every case, because it was in every case.

I think you’re assuming good faith on the part of “black confederate” crowd. At worse they’re dishonest, like the hawkers of the “First Native Guards” fake photo, at best, they are happy with big noisy face of Oz, they don’t want to know about the man behind the curtain.

Matt, thanks for commenting. You’re right that there’s much outright dishonesty out there when it comes to “black Confederates,” although it’s often hard to tell who’s being dishonest and who’s simply repeating inaccurate or misunderstood information. Ann DeWitt, for example, has shown pretty conclusively (IMO) that she doesn’t even understand the criticism leveled at her website, or the larger historical context against which she’s making the claims she does.

The “Louisiana Native Guards” photo you mention is a particularly egregious case, in that it’s been conclusively established to be a fraud. It’s not a case of misinterpretation or “spin”; someone intentionally modified an historic image for the purpose of deceiving others. And that unknown person has been very successful at it; you can still find that falsified image on any number of websites today. That, to me, is more problematic, continuing to present it as photographic evidence of “black Confederates” long after it was exposed as a fake.

As for not wanting “to know about the man behind the curtain,” it really does seem to me (as Kevin regularly points out) that the actual history of these men, and the context of the world in which they lived, is entirely irrelevant to those who present them as “black Confederates”; all that matters is finding a way to check them off as another black guy in butternut.

“The “Louisiana Native Guards” photo you mention is a particularly egregious case, in that it’s been conclusively established to be a fraud. It’s not a case of misinterpretation or “spin”; someone intentionally modified an historic image for the purpose of deceiving others. And that unknown person has been very successful at it; you can still find that falsified image on any number of websites today. That, to me, is more problematic, continuing to present it as photographic evidence of “black Confederates” long after it was exposed as a fake.”

Andy,

Yes, this is what really stands out for me! There are always people willing to perpetrate hoaxes, often just to see if they can pull it off. But the fact that this doctored pic remains on websites after having been exposed as fraudulent speaks volumes about the motives and ethics of those pushing the “black Confederate” narrative.

This is a great post; I love good historical detective work!

Marc

This is a wonderful example of the kind of research and analysis that we need to bring to bear on this subject. Thanks Andy

How to refute a claim? Bit by historical bit.

Nice!

Andy: You are good. Your blog is terrific. And this is a great post.

Thanks very much.

Andy,

This is a great demonstration of how someone does historical research.

You’re so right.

I know the highest ranking officer of African descent in the Confederacy…and it wasn’t James Kemp Holland.

Texas State Gazette (Austin, Travis Co., TX), Tues, 4 Apr 1854, p. 220, c. 3 – By a letter from the happy bridegroom, we learn that our old friend Col. James K. Holland of the State Senate, was married to Miss Samuella Andrews of Harris county, on the 22nd of last month (22 Mar 1854), in the city of Houston.

.

Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph (Houston, Harris Co., TX), Wed., 18 Oct 1865, p. 4, c. 5 – DIED – At Farmington, Grimes county, on Thursday, the 5th inst (5 Oct 1865), after a painful illness, Samuella Andrews, wife of J. K. Holland. This bereavement is rendered doubly afflictive, by the death a few weeks before of their only son, 7 years, and a daughter 5 years of age, both with an hour of each other.

.

Samuella Andrews was the daughter of John Day Andrews & Eugenia Price. He was the 5th Mayor of the City of Houston. They are buried in the Glenwood Cemetery, Houston, Harris Co., TX. Her sister, Eugenia Andrew married Robert Turner Flewellen. They are buried in the Glenwood Cemetery, Houston, Harris Co., TX.

.

Thanks — that’s fantastic. Updating the profile above. That same issue of the paper includes a separate obit notice for the children.