Diamonds are a Trooper’s Best Friend

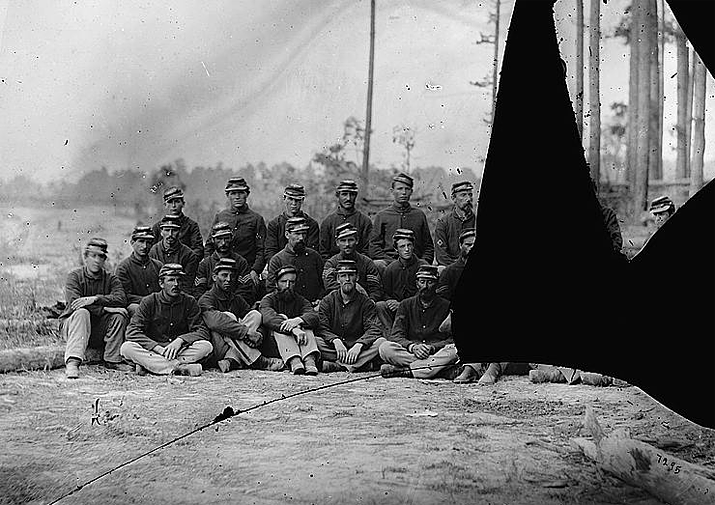

The historic photo blog Shorpy put up an image Sunday of Company C, 1st Massachusetts Cavalry. The original image, on a broken glass plate negative, is from the Library of Congress. It’s identified as “Petersburg, Virginia. Company C, 1st Massachusetts Cavalry,” and is one of four images (others here, here and here) taken of this unit in August 1864. Shorpy has a lot of CW images on the site.

One of the neat things about Shorpy is that it offers images in high resolution, allowing users to pick out all sorts of detail. In this case, I noticed the man seated in the back row, next to the break in the plate. On the sleeve of his sack coat he wears a single diamond, properly termed a lozenge, where the chevrons would be — like that of a first sergeant, but without the stripes. I know that cavalry units had designations that infantry and artillery units didn’t — farriers, saddlers, etc. — but the chevrons I’ve seen with those ranks all carried stripes and (I think) weren’t introduced as having distinct insignia until sometime after the war.

Here is a closeup of the man in question, along with a another closeup of the same man from this image (standing, far left), labeled as “Petersburg, Va. Commissioned and noncommissioned officers of Cos. C and D, 1st Massachusetts Cavalry”:

So what’s a solitary diamond signify?

I passed this along to J. David Petruzzi, who blogs at Hoofbeats and Cold Steel, and asked if he’d seen similar images. He hadn’t, but his initial thought was something I hadn’t considered:

I wonder if maybe it’s meant to be seen by your troops, but not so easily by the enemy? Later in the war, even officers started wearing shoulder boards without the gold trim so they wouldn’t be so easily targeted. In infantry and cavalry, if you take out the sergeant, you can leave a part of a company leaderless.

That sure makes sense to me. J. D. then put it up on his Facebook page, and several folks responded that they’d seen similar practice. The consensus seemed to be just as J. D. had suggested, that it was the Civil War equivalent of modern “subdued” rank insignia, designed to be clearly visible up close, but not so prominent to make the wearer a target for marksmen.Then there’s this, from a discussion of Union cavalry uniforms in Don Troiani’s Regiments & Uniforms of the Civil War:

Although army regulations called for the chevrons to be worn above the elbow on each sleeve of the jacket or blouse, numerous entries in the regimental order books attest to the fact that sergeants and corporals were often negligent when it came to sewing them on. Several reasons may account for this, not the least of which is that they had to pay for them. It may also be that the bright yellow stripes of command offered an inviting target for enemy sharpshooters. Whatever the reason, orders are abundant instructing those who failed in this regard to adhere to regulations. [1]

So for now, let’s call him First Sergeant of Co. C., 1st Massachusetts Cavalry.

Can we go further than this? Possibly.

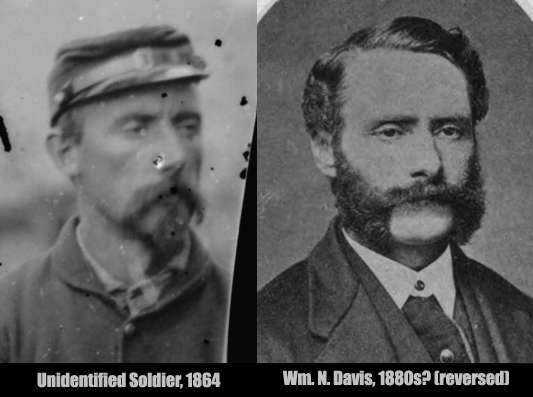

NARA’s compiled service records for the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry are not digitized, but Benjamin W. Crowninshield’s History of the First Regiment of Massachusetts Cavalry Volunteers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1891) identifies the First Sergeant of Co. C during the latter part of the war as William Nickerson Davis (right, in a postwar photo from the book). Davis was born in Needham, Massachusetts on September 17, 1837 (twenty-five years to the day before the battle of Sharpsburg), the great-grandson of an officer in Enoch Hale’s Regiment (15th New Hampshire Militia) at Ticonderoga. Davis enlisted in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in December 1861, at the age of 24. He was promoted to Corporal in August 1863, and to Sergeant in March 1864. The date of his promotion to First Sergeant is not known; he mustered out in December 1864 along with most of the regiment, after their three-year term of service expired. After the war he moved to Illinois, where in 1873 he married Martha Hulen (1836-97), a North Carolina native (presumably widowed) with a young son, Samuel. Two more sons, Thurough and Jesse, and a daughter, Sarah, had been born by 1877. Davis farmed and worked as a painter in the town of Bellflower, Illinois, but by the time of the 1900 U.S. Census, now widowed, Davis was living alone with his grown daughter Sarah. William Nickerson Davis died on June 15, 1923, and was buried in Bellflower Township Cemetery. [2]

NARA’s compiled service records for the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry are not digitized, but Benjamin W. Crowninshield’s History of the First Regiment of Massachusetts Cavalry Volunteers (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1891) identifies the First Sergeant of Co. C during the latter part of the war as William Nickerson Davis (right, in a postwar photo from the book). Davis was born in Needham, Massachusetts on September 17, 1837 (twenty-five years to the day before the battle of Sharpsburg), the great-grandson of an officer in Enoch Hale’s Regiment (15th New Hampshire Militia) at Ticonderoga. Davis enlisted in the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in December 1861, at the age of 24. He was promoted to Corporal in August 1863, and to Sergeant in March 1864. The date of his promotion to First Sergeant is not known; he mustered out in December 1864 along with most of the regiment, after their three-year term of service expired. After the war he moved to Illinois, where in 1873 he married Martha Hulen (1836-97), a North Carolina native (presumably widowed) with a young son, Samuel. Two more sons, Thurough and Jesse, and a daughter, Sarah, had been born by 1877. Davis farmed and worked as a painter in the town of Bellflower, Illinois, but by the time of the 1900 U.S. Census, now widowed, Davis was living alone with his grown daughter Sarah. William Nickerson Davis died on June 15, 1923, and was buried in Bellflower Township Cemetery. [2]

Is the (presumed) First Sergeant in the LoC photos William Nickerson Davis? Compare images:

The soldier is thin, even gaunt, and deeply tanned. But there is, to me, a resemblance.

J. D.’s not so sure, arguing that the end of the nose and the jaw line are very different. One of J. D.’s colleagues on Facebook suggests the soldier in the photo might be another member of Company C, Commissary Sergeant Ethan E. Cobb (1826-1884). Here is Cobb’s postwar photo, compared with wartime image:

There’s a strong resemblance with Cobb, too – maybe more than for Davis. But still, there’s that lozenge on the man’s sleeve, and Davis was (near as I can tell) First Sergeant of the company at the time the photograph was made — not Ethan Cobb. Would the lozenge fit for a Commissary Sergeant as well?

What do you think?

[1] Earl J. Coates, Michael J. McAfee and Don Troiani, Don Troiani’s Regiments & Uniforms of the Civil War (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 2002), 181.

[2] In addition to Crowninsheild’s regimental history outlining Davis’ wartime service, there are numerous records available via Ancestry that document his civilian life, including census and death records. Of particular value is Jesse Davis’ 1923 application for membership in the Sons of the American Revolution, also via Ancestry, that provides additional data on William N. Davis’ genealogy.

Wow, excellent trip though history. I’m going with Davis as the match. Eyelids, nose and eyebrows match fairly well. Shape of eyes wouldn’t change between mid 20’s and mid 40’s. Can’t match jawline because of muttonchops.

I’m inclined that Cobb is a better match for the image, but Davis is the one who, based on the regimental history, “ought” to be the one in the photo.

Fun stuff.

In regards to the diamond, it may be just a way to keep from being shot. I know in the western theater you see cases where NCOs and Officers really tone down their rank insignia. In the Army of the Cumberland, at least with officers there was a General Order from Rosecrans telling them to reduce their rank insiginia, you can see this in several images of officers from that time period, the most famous being of Albion Tourgee and two other officers of the 105th Ohio Infantry.

I’m not convinced either civilian is a match with the CW soldier. I’m stuck on the shape of the noses, particularly the downward-drooping and slightly-rounded tip and more flared/arched nostrils of the two civilian photos compared to the large, almost isoceles triangle shape and pointy tip of the soldier’s nose (see esp. the soldier’s standing photo for a better sense of his nose shape and size relative to the face).

Yes, the subject is thinner in the war photos and would be expected to have gained some weight after the war, but I assume the size, proportions and shape of the nose are less variable due to weight loss or gain than other parts of the face (since it’s mostly cartilage and skin). But maybe this assumption is incorrect. Any doctors or pathologists wish to chime in?

No clue about the diamond shaped badge, either.

Thanks for the post.

I agree with Reed – the ear whorls don’t match either. Would a cavalry unit have a quartermaster sergeant – they apparently wore a diamond-shaped badge? And the badge of the 4th Corps – Army of the Potomac – was a red triangle.

http://www.globalsecurity.org/military/agency/army/corps-civil-war-badges-1.htm

Quartermaster sergeants wore three stripes with three horizontal ties above them.

I’ve never seen or heard of soldiers wearing their corps badge on their sleeves. Cavalry units were usually not attached to infantry corps, and the 1st Massachusetts wasn’t part of the 4th Corps. A red badge only indicated the first division of a corps; the second division wore a white badge, and the third division a blue one: http://howardlanham.tripod.com/linkgr3/link151.html

I would not rule out some localized insignia for either the farrier or saddler. I don’t think those were standardized until after the war, however.

I’m not sure about the subdued rank theory here. If hiding the rank is part of the scheme, why not just go with a miniature version of the normal insignia, or at least darker color. Or even just dispense with it all together?

I’m with Craig, the problem with the subdued rank theory is that there are two sergeants and a corporal sitting there wearing quite visible chevrons.

Although, there’s not an abbreviated way to show those ranks, indicated by the chevrons themselves. A topkick’s rank can be indicated by the lozenge alone, no?

Still, an intriguing question.

Uniform standards in veteran regiments were often lax. I wouldn’t be surprised if NCOs within the same company or regiment wore their insignia differently.

Fun stuff, indeed.

But take a look at one of the other photos of these men (your third “here” link, large image at: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/master/pnp/cwpb/03700/03767u.tif )

The soldier seated front row, far left (in front of our standing mystery-insignia subject) sure looks like Sgt. Wm. N. Davis, with the rounded-tip nose, distinctive facial hair and three large chevrons on each sleeve. (Perhaps you can imbed the photo here, Andy?)

The row of standing men has two additional soldiers with 3 chevrons. I think its possible that the man standing fourth from the right might be Ethan E. Cobb (see esp. his eyes/eyebrows, nose and ear lobes)

What do you think? Maybe you could post these face closeups for comparison?

Interesting. One important caveat, though — that image is captioned as including men from both C and D Companies, so the pool of men they could be is doubled.

Andy,

I agree with your pick for Wm Davis at the bottom of the two pairs of photos in your post. Same straight brow/eyebrows; same facial hair; same forehead hairline (of what’s visible); same or similar ears (a bit too blurry in 1864 photo to be sure); very similar nose (slightly differerent angles). Eyes a bit sunken in 1864 photo (understandably), but still very similar to the 1880’s photo.

I think your Cobb pick is also good, though not as conclusive as your Davis pick. Ears are almost as identifying as fingerprints. Though the 1864 ears if rather blurry, it seems to bear a strong resemblemce to the 188’s Cobb photo.

Good detective work, Andy.

Andy- I think you need someone who can do a forensic analysis of ear shapes…. the shape of a person’s ear is almost as unique as fingerprints are. I don’t know if the images are clear enough for it to be done but it’s the only angle I can think of for closer I.D.

Good post.

I agree Wilbur ,,and that person is Colleen Fitzpatrick Forensic Genealogist

http://www.forensicgenealogy.info/index.htmly

She has a weekly puzzler and I bet she would love to include this puzzler

In the original cracked image, the leftmost Sergeant (i.e. 3 chevons, sitting in middle row directly beneath the soldier second from left in backrow) looks to me to be the best candidate for being William N. Davis. (Download the tif file from the LOC so that you can magnify at high resolution)

Mark, thanks. I’ll have a look later — I routinely download these files in TIFF format, then knock ’em back down for use here online. It’s a remarkable and valuable service the LoC does in providing these images.

Those with an interest in uniforms should check out “Military Images” magazine, which reprints photos of U.S. military personnel in the 19th century and includes a great deal of information on uniforms and equipment. Some years ago they did a special issue on Union Army rank insignia. Sure enough, there were photographic examples of first sergeants (often named and identified) wearing just the lozenge. they could have done it for any number of reasons. The vast majority of Civil War soldiers were volunteers and often cared little for uniform regulations.

Noticed that the officer in your group photo http://lcweb2.loc.gov/service/pnp/cwpb/03700/03767v.jpg is Charles Francis Adams Jr., Grandson of John Qunicy Adams ..

Very nice, thanks. I’ll probably bump that up to a post on its own.

Great Andy 🙂

Those men of Company C, 1st Massachusetts Cavalry they were Confederates or Union Soldiers? Sorry if that may sound a stupid question but I am not from the U.S and I’ve read many articles recently about the Civil War and clearly is very interesting topic.

Union soldiers.

>> The original image, on a broken glass plate negative, is from the Library of Congress.

Not sure why you’re calling the broken plate the “original image.” It’s an entirely different photograph.

That blog post was written last January; the “original image” referenced at Shorpy is this one.