Nathan Bedford Forrest Joins the Klan

Nathan Bedford Forrest is always a popular subject in Confederate heritage, but that’s never been more true than it is today. He’s frequently featured in the secular trinity of Confederate heroes, alongside Lee and Jackson. And like those two – and only those two – Forrest has achieved the modern apotheosis of Confederate fame, having his own page of t-shirts at Dixie Outfitters.

Nathan Bedford Forrest is always a popular subject in Confederate heritage, but that’s never been more true than it is today. He’s frequently featured in the secular trinity of Confederate heroes, alongside Lee and Jackson. And like those two – and only those two – Forrest has achieved the modern apotheosis of Confederate fame, having his own page of t-shirts at Dixie Outfitters.

But Forrest’s defenders often hold the line at one claim, that he was a prominent figure in the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan. Even as they struggle to rationalize the Klan of that period as a necessary counter against the supposed excesses of the Union League and other northern influences, they usually deny any involvement of Forrest in the Klan’s organizing or activities, except for the odd claim that Forrest, despite having no authority or connection to the group, successfully ordered them to stand down in 1869.

So did Forrest really join the Ku Klux Klan? Yes, he did. Was he really Grand Wizard of the group? Yes, he was. How do we know this? Because the old klansmen who were there tell us so.

Forrest’s order to disband the group is something that Forrest’s supporters generally agree upon — they’ll credit him with stopping the Klan’s violence, though never supporting it, or being involved with it — but that order makes little sense when coupled with the assertion that the former general had no other connection to the group. Why would such an order come from Forrest, exactly? Sure, he was a well-known and popular figure after the war, but there were other former Confederate leaders who ranked him, both in actual seniority and in the public’s mind. Why not Robert E. Lee, or Jefferson Davis? (Or Johnston, or. . . ?) Are we to supposed to assume these men would have no influence, no moral authority with the klansmen? No, Forrest’s order — and the assertion that it was accepted and followed — only makes sense if those men understood Forrest to have been a leader within the organization, with the authority to issue such a directive.

Forrest’s defenders often point to his testimony before a congressional investigation in June 1871, in which he denied personal involvement with the Klan, but seemed to nonetheless know quite a bit about it generally. That he denied involvement in the group is taken at face value, ignoring the fact that we can all name a long list of folks who’ve routinely lied to Congress about issues serious and silly, when they’re liable to incriminate themselves. Forrest’s fans will sometimes say he was “acquitted” by the investigation, but that’s inaccurate, because he was never tried as a criminal matter. Moreover, the committee was not charged with investigating Forrest’s personal involvement in their first place, and acknowledged the difficulty they had in getting anyone to testify about the group at all, given the secret nature of the organization and the retribution likely waiting for any member who spoke about it publicly.[1]

To the Klan and its supporters, though, Forrest’s denials under oath were simply part of his role:

When before the Ku Klux Committee of Congress, in 1871, the General would make only general statements and he evaded some of the interrogatories. To the committee he appeared to be wonderfully familiar with the principles of the order, but very ignorant as to details. The average member of Congress, ignorant of Southern conditions, did not understand that the members of the order considered themselves bound by the supreme oath of the Klan and that other oaths, if in conflict with it, were not binding. That is, the ex-Confederates under the command of Forrest, Grand Wizard of the Invisible Empire, were obeying the first law of nature and were bound to reveal nothing to injure the cause, just as when Confederates under Forrest, Lieutenant-General of the Confederate Army, they were bound not to reveal military information to the hostile forces. The government, in their view, had not only failed to protect them, but was being used to oppress them. Consequently they were disregarding its claim to obedience.[2]

In short, Forrest played them.

![]()

Forrest’s supporters will also cite a short address he gave in 1875 to a black Memphis civic group, the Pole Bearers’ Association, as evidence that he bore no ill will toward African Americans in general. Referring to hopes for a “reconciliation between the white and colored races of the southern states,” Forrest urged his audience to exercise their right of suffrage, and closed with the lines,

I want you to come nearer to us. When I can serve you I will do so. We have but one flag, one country; let us stand together. We may differ in color, but not in sentiment Many things have been said about me which are wrong, and which white and black persons here, who stood by me through the war, can contradict. Go to work, be industrious, live honestly and act truly, and when you are oppressed I’ll come to your relief.

To be sure, these are not the words one would expect to hear from a leader of the Klan. But neither are they the words one would expect from a man who, not a great many years before, had made a sizable fortune as a slave trader.

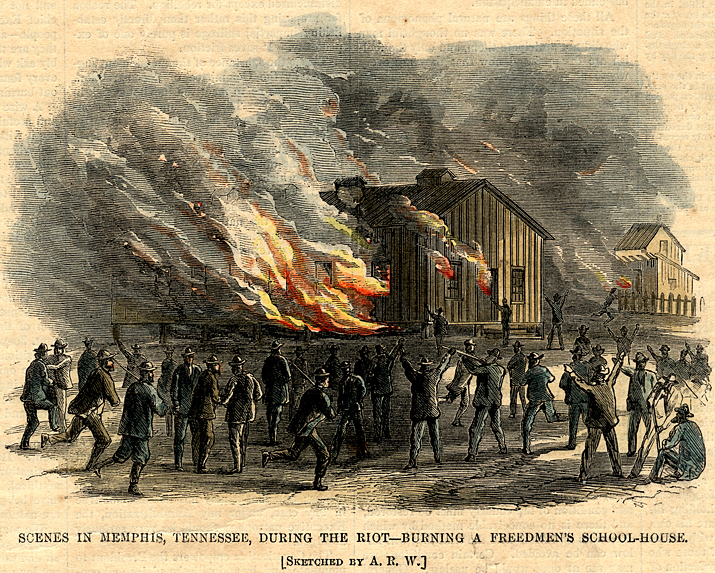

Engraving after a sketch by Alfred R. Waud in Harper’s Weekly, depicting some of the violence during rioting in Memphis in early May 1866. At the end of three days of violence, forty-eight people were dead — forty-six black, and two white. (One of the latter was killed by the accidental discharge of his own weapon.) Via Tennessee State Library and Archives.

More important, much had changed in the decade between 1866, when Forrest reportedly joined the Klan, and 1875, when Forrest addressed the Pole Bearers. Memphis had been the scene of violent recriminations against both newly-freed African Americans and military and civilian personnel involved in Reconstruction. By the mid-1970s, though, much had changed. The Democrats had won control of the state’s General Assembly in 1869, and withdrew state funding from public schools established by the previous, Republican assembly for both poor white and black students. Tennesseee’s Reconstruction governor William G. Brownlow, the Klan’s primary enemy in the state government, had resigned that same year to accept a seat in the U.S. Senate. A new state constitution had been adopted in 1870 that gave the right to vote to African Americans, but made suffrage contingent upon payment of a poll tax, a tactic that effectively disenfranchised most African Americans for decades to come.[3] In short, by 1875 Tennessee was well on its way to re-establishing the antebellum social and racial order, and groups like the Pole Bearers posed little real challenge to the re-assertion of white power in the state. Men like Forrest could afford to be magnanimous with their words.

But by 1875, two years before his death, Forrest was a different man, as well. The Pole Bearers’ speech had attracted attention, after all, specifically because it was such an unusual counterpoint to his well-established reputation. It was viewed at the time as a strange event. The Newport, Connecticut Daily News remarked that “lest the colored people forget who Forrest was, the Fates so ordered things that Gen. [Gideon Johnston] Pillow addressed them on the same occasion. There can be nothing in a name, if Forrest accompanied by a Pillow would have been too much for the self-possession of any colored person.” The Chicago Inter-Ocean observed that the event marked a recognition of the rights of African Americans, “even by such bitter opponents of equality and Forrest and Pillow.” The New Orleans Times noted that “of the Southern leaders in the late war, none have been considerated [sic.] as dangerous an enemy as the famous trooper Forrest.”[4] But if Forrest’s appearance before the Pole Bearers was seen as progress and reconciliation by some, others wanted no part of it. Describing the event as “the recent disgusting exhibition of himself at the negro [sic.] jamboree,” the Macon Weekly Telegraph quoted the Charlotte, North Carolina Observer as saying that

we have infinitely more respect for [James] Longstreet, who fraternizes with negro men on public occasions, with the pay for the treason to his race in his pocket, than with Forrest and Pillow, who equalize with the negro women, with only ‘futures’ in payment.[5]

The Nathan Bedford Forrest of 1875 was not the Nathan Bedford Forrest of 1866.

![]()

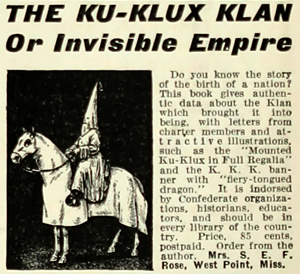

More broadly, this obstinate denial about Forrest’s involvement with the Klan runs counter to generations of Southerners’ understanding about Forrest; it is revisionist white-washing at its most blatant, an open attempt to make the old slave trader conform to a modern, politically-correct standards of racial tolerance. But real Confederates, and real klansmen, had no doubt whatsoever that Forrest was one of them. One of the first attempts at a narrative history of the Reconstruction-era Klan, written by Laura Martin Rose of West Point, Mississippi, former president and historian of the Mississippi UDC, was explicit about Forrests’ involvement, giving him the title of “Grand Wizard of the Invisible Empire.” Rose was a native of Giles County, Tennessee, the birthplace of the Klan.[6] Rose’s booklet, sold to raise funds for a monument to Jefferson Davis at Beauvoir, was both excerpted and advertised for sale (above right) in the Confederate Veteran magazine, a journal written by and for former Confederate soldiers and their families. Confederate Veteran was one of the major voices at the time projecting an explicitly Southern view of the conflict, its causes and consequences.[7] Rose’ account not only made clear Forrest’s role in the Klan, but defended that organization’s reputation on the basis of his involvement, and credits to him what she sees as the group’s success:

More broadly, this obstinate denial about Forrest’s involvement with the Klan runs counter to generations of Southerners’ understanding about Forrest; it is revisionist white-washing at its most blatant, an open attempt to make the old slave trader conform to a modern, politically-correct standards of racial tolerance. But real Confederates, and real klansmen, had no doubt whatsoever that Forrest was one of them. One of the first attempts at a narrative history of the Reconstruction-era Klan, written by Laura Martin Rose of West Point, Mississippi, former president and historian of the Mississippi UDC, was explicit about Forrests’ involvement, giving him the title of “Grand Wizard of the Invisible Empire.” Rose was a native of Giles County, Tennessee, the birthplace of the Klan.[6] Rose’s booklet, sold to raise funds for a monument to Jefferson Davis at Beauvoir, was both excerpted and advertised for sale (above right) in the Confederate Veteran magazine, a journal written by and for former Confederate soldiers and their families. Confederate Veteran was one of the major voices at the time projecting an explicitly Southern view of the conflict, its causes and consequences.[7] Rose’ account not only made clear Forrest’s role in the Klan, but defended that organization’s reputation on the basis of his involvement, and credits to him what she sees as the group’s success:

His high standing as a Confederate officer, his devotion to his country, his noble principles and sacred honor pledged to protect the South, puts at naught forever any false statements as to the purposes of the Klan, and challenges any stigma or misrepresentations as to the character of its members, for they were in the main Confederate soldiers, and Forrest was its great leader, and under his leadership and with the loyalty of the members, the Mission of the Ku Klux Klan, or Invisible Empire, was successfully accomplished.[8]

Rose’s source on Forrest’s involvement with the Klan is unimpeachable: former Major James R. Crowe (right), one of the original six founders of the Klan at Pulaski, Tennessee. In her booklet, she reprints a letter Crowe wrote her, describing the Klan’s desire to elevate Forrest to the senior leadership:

Rose’s source on Forrest’s involvement with the Klan is unimpeachable: former Major James R. Crowe (right), one of the original six founders of the Klan at Pulaski, Tennessee. In her booklet, she reprints a letter Crowe wrote her, describing the Klan’s desire to elevate Forrest to the senior leadership:

The younger generation will never fully realize the risk we ran, and the sacrifices we made to free our beloved Southland from the hated rule of the “Carpetbagger,” the worse negro [sic.] and the home Yankee. Thank God, our work was rewarded by complete success. After the order grew to large numbers, we found it was necessary to have someone of large experience to command. We chose General N. B. Forrest, who had joined our number. He was made a member and took the oath in the Room No. 10 of the Maxwell House at Nashville, Tennessee, in the fall of 1866, nearly a year after we organized at Pulaski. The oath was administered to him by Captain John W. Morton, afterwards Secretary of State, Nashville, Tennessee.[9]

Rose concludes, in laying out the great lessons taught by the Klan:

First, the inevitability of Anglo-Saxon Supremacy; when harassed by bands of outlaws, thugs, carpet-baggers, and guerillas, turned loose on the South and upheld by political machinery, during the Reconstruction period, the sturdy white men of the South, against all odds, maintained white supremacy and secured Caucasian civilization, when its very foundations were threatened within and without. Second, a new revelation of the greatness and genius of General Nathan Bedford Forrest, the “Wizard of the Saddle,” the great Confederate cavalry leader. As Grand Wizard of the Invisible Empire, to his splendid leadership was due, more than to any other.[10]

Rose’s volume, with her claim about Forrest, was subsequently endorsed by the Sons of Confederate Veterans, who pledged “to ‘assist in every way possible to promote its circulation and to cooperate in getting this work in the schools and public libraries’ that the origin and objects of that great order may be more generally known and understood.”[11]

Crowe’s first-hand account of the decision to select Forrest for leadership in the group is compelling, but there’s more. John Watson Morton (1848-1920, right), Forrest’s former artillery commander, remained a friends with Forrest until the latter’s death. He went on to serve as the Tennessee Secretary of State. The Sons of Confederate Veterans dedicated a monument at Prker’s Crossroads to Morton and his battery in 2007. Morton’s 1909 autobiographical account, The Artillery of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Cavalry: The Wizard of the Saddle, focuses on the war years, but includes a detailed essay on the Ku Klux Klan written by Thomas Dixon, Jr. The account is an expanded version of a piece Dixon published a few years previously in the September 1905 issue of The Metropolitan Magazine in a story on the fawning story on the group, written by Thomas Dixon, Jr., the same year as he published the novel, The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, which would in turn become the basis for Griffith’s infamous screen spectacular, Birth of a Nation. Forrest himself gets a passing mention in The Clansman, referred to as “a great Scotch-Irish leader of the South from Memphis.”[12] Few readers could be in doubt, then, as to whom Dixon refers to in his historical precis where he says “society was fused in the white heat of one sublime thought and beat with the pulse of the single will of the Grand Wizard of the Klan at Memphis.”[13]

Crowe’s first-hand account of the decision to select Forrest for leadership in the group is compelling, but there’s more. John Watson Morton (1848-1920, right), Forrest’s former artillery commander, remained a friends with Forrest until the latter’s death. He went on to serve as the Tennessee Secretary of State. The Sons of Confederate Veterans dedicated a monument at Prker’s Crossroads to Morton and his battery in 2007. Morton’s 1909 autobiographical account, The Artillery of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Cavalry: The Wizard of the Saddle, focuses on the war years, but includes a detailed essay on the Ku Klux Klan written by Thomas Dixon, Jr. The account is an expanded version of a piece Dixon published a few years previously in the September 1905 issue of The Metropolitan Magazine in a story on the fawning story on the group, written by Thomas Dixon, Jr., the same year as he published the novel, The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, which would in turn become the basis for Griffith’s infamous screen spectacular, Birth of a Nation. Forrest himself gets a passing mention in The Clansman, referred to as “a great Scotch-Irish leader of the South from Memphis.”[12] Few readers could be in doubt, then, as to whom Dixon refers to in his historical precis where he says “society was fused in the white heat of one sublime thought and beat with the pulse of the single will of the Grand Wizard of the Klan at Memphis.”[13]

Getting back to Dixon’s non-fiction, Dixon’s Metropolitan Magazine article is predictably rancid in its inflammatory portrayal of African Americans (“the lowest type of negro, maddened by these wild doctrines, began to grip the throat of the white girl with his black claws. . . “), but it’s also unequivocal on Forrest’s leadership in the Klan. It gives a detailed and specific account of Forrest seeking out Morton, his old comrade, and pressing him to be accepted into the group. Morton was, according to his own autobiography, Grand Cyclops of the Nashville Den of the Klan.[14] Dixon’s account is compelling, in part, because it includes details that must have come from Morton himself, that describe exchanges between the two men that were not witnessed by anyone else, and could only have been related by Morton.

Maxwell House in Nashville, Tennessee, c. 1900. Forrest was sworn into the Ku Klux Klan here in the fall of 1866, and the first national meeting of the group was reportedly held here the following spring. The structure was destroyed in a fire on Christmas night, 1961. Image via Tennessee State Library and Archives.

Morton himself must have been pleased with Dixon’s account in the Metropolitan Magazine, because he used an expanded, more detailed version of it in his own autobiography. It includes much detail, and is worth quoting in full:

One of the most interesting figures in the inner history of the clan is that of Hon. John W. Morton, formerly Secretary of the State of Tennessee, who was General Forrest’s chief of artillery. Pale and boyish in appearance, he was, in fact, but a boy, yet he won the utmost confidence of the General, who relied on him as Stuart did on Pelham and Lee on Jackson. Forrest called him ‘the little bit of a kid with a great big backbone.’ When the rumors of the Kuklux [sic.] Klan first spread over Tennessee, General Forrest was quick to see its possibilities. He went immediately to Nashville to find his young chief of artillery.

“Captain Morton then had an office diagonally across from the Maxwell House. Looking from his window one day, he saw General Forrest walking impatiently around Calhoun Corner, as it was then called. Hastening down the steps to greet his former chieftain, he encountered a little negro [sic.] boy, who inquired where he could find Captain Morton. He said: ‘There’s a man over yonder on de corner and he wants to see him, and he looks like he wants to see him mighty bad.’ Captain Morton hurried across the street, and, after salutation, the General said: ‘John, I hear this Kuklux Klan is organized in Nashville, and I know you are in it. I want to join.’ The young man avoided the issue and took his Commander for a ride. General Forrest persisted in his questions about the Klan and Morton kept smiling and changing the subject. On reaching a dense woods in a secluded valley outside the city, Morton suddenly turned on his former leader and said: ‘General, do you say you want to join the Kuklux?’

General Forrest was somewhat vexed and swore a little: ‘Didn’t I tell you that’s what I came up here for?’

Smiling at the idea of giving orders to his erstwhile commander, Captain Morton said: ‘Well, get out of the buggy.’ General Forrest stepped out of the buggy, and next received the order: ‘Hold up your right hand.’

General Forrest did as he was ordered, and Captain Morton solemnly administered the preliminary oath of the order.

As he finished taking the oath General Forrest said: ‘John, that’s the worst swearing that I ever did.’

‘That’s all I can give you now. Go to Room 10 at the Maxwell House to-night and you can get all you want. Now you know how to get in,’ said Captain Morton.

After administering the oath to his chieftain, Captain Morton drove him to call on a young lady, and after a short visit in the parlor, Miss H. saw them out to the door. General Forrest led her to the end of the porch, and Captain Morton overheard him saying: ‘Miss Annie, if you can get John Morton, you take him. I know him. He’ll take care of you.’

That night the General was made a full-fledged clansman, and was soon elected Grand Wizard of the Invisible Empire. . . .[15]

![]()

None of this will sway the thinking of those who have chosen to believe Forrest had no involvement with the Klan. But for those with an open mind, accounts like Crowe’s and Morton’s are impossible to dismiss. Folks can, and will, believe whatever they want to, but for those who really want to know, the evidence has been there all along.

[1] Report of the Joint Select Committee Appointed to Inquire Into the Condition of Affairs in the Late Insurrectionary States. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1872), 14.

[2] J. C. Lester and D. L .Wilson, Ku Klux Klan: Its Origin, Growth and Disbandment (New York: Neale Publishing, 1905), 27-28.

[3] Antoinette G. van Zelm, “Hope Within a Wilderness of Suffering: The Transition from Slavery to Freedom During the Civil War and Reconstruction in Tennessee.” Tennessee State Museum, http://www.tn4me.org/pdf/TransitionfromSlaverytoFreedom.pdf. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

[4] Newport Daily News, 13 July 1875, 2; Chicago Inter-Ocean, 14 July 1875, 4; New Orleans Times, 7 July 1875, 4.

[5] Macon Weekly Telegraph, 20 July 1875, 4.

[6] “Mississippi Division, U.D.C.,” Confederate Veteran magazine, July 1909, 352.

[7] Laura Martin (Mrs. S. E. F.) Rose, “The Ku-Klux Klan and ‘The Birth of a Nation,” Confederate Veteran magazine, April 1916, 157-59.

[8] Laura Martin (Mrs. S. E. F.) Rose, The Ku Klux Klan: or Invisible Empire (New Orleans: L. Graham Co., 1914), 78-79.

[9] Rose, Invisible Empire, 21-22.

[10] Rose, Invisible Empire, 51-52.

[11] “Activities in the Association,” Confederate Veteran magazine, October 1914, 445. The magazine frequently mentioned individuals’ involvement with the Reconstruction-era Klan, either explicitly or using euphemism (e.g., “he was familiar with the organization of the Ku Klux Klan in Giles County”); these examples are never depicted as a negative thing; rather they’re something to be applauded. As examples, see “Carson T. Orr,” Confederate Veteran magazine, December 1916, 529; “William Easley Loggins,” Confederate Veteran magazine, July 1916, 321; “John Booker Kennedy,” Confederate Veteran magazine, May 1913, 240; “Col. Asa E. Morgan,” Confederate Veteran magazine, February 1910, 89.

[12] Thomas Dixon, Jr. The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1905), 296.

[13] Dixon, 343.

[14] John Watson Morton, The Artillery of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Cavalry: The Wizard of the Saddle (Nashville: Publishing House of the M. E. Church, South, 1909), 338.

[15] Morton, 344-45.

_______________

Very nice piece. I’ve always been intrigued by his story and how confusing it really is. I also liked your analysis of how he changed over time from 1866 to 1876. Good work Andy.

I wonder how many present-day SCV members realize that a hundred years ago — back when the Sons of Confederate Veterans were actually the sons of Confederate veterans — that group formally and publicly endorsed a book that named Forrest as Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, which “maintained white supremacy and secured Caucasian civilization.”

I’d say not a whole lot.

Excellent.

KKK has a slightly different meaning in the Philippines. It referred to a secret society known as the Kapitunan, for short, which was dedicated to overthrowing the Spanish colonial government during the decade in which that event occurred. It failed to translate into resistance to American colonial occupation, in part because the American intervention was engineered to some considerable extent by influential Filipinos in America. It’s not clear if the name of the organization was meant to suggest in some way that its structure was in some way modeled upon the organization in the U.S. with the same initials, although it was definitely a secret order with potentially dire consequences for members discovered to belong by colonial authorities.

That’s interesting, I didn’t know that. I can see how the letters KKK might be picked up because of its association with a secret, mysterious insurgency, but I imagine the parallels otherwise were superficial. IIRC the letter K also is rarely used in conventional Spanish, so any reference to an organization using that letter would immediately stand out as distinctive.

Many Tagalog (Filipino) words begin with the letter “K,” including a few borrowed from Spanish (where they began with “C”). But the “KKK” found in Philippine history has nothing whatsoever to do with either the Ku Klux Klan or any Spanish roots. It stands for “Kataastaasan, Kagalanggalang Katipunan” (Supreme and most Honorable Society”), part of a longer title, nowadays usually just referred to as the “Katipunan,” the revolutionary organization that rose up against Spanish rule and continued to fight the Americans when they invaded. So it’s an interesting coincidence, nothing more.

“Good to last drop” Andy. Coffee n’ Klan – all from the same building.

I was wondering who’d catch that.

Of course, second and third hand accounts and newspaper stories must be counted as solid historical truth if it backs up what we **want** to believe.

I wouldn’t consider Crowe’s letter to be a second- or third-hand account. Neither would I consider Morton’s decision to use Dixon’s essay in his own autobiography to be a second-hand account. The Metropolitan Magazine version is one thing; Morton’s decision to include an expanded version of it in his own autobiography is another thing altogether. Morton embraced it, Morton reprinted it, and so he owns it.

I’m sure you noticed that the SCV endorsed Laura Martin Rose’s book in which Crowe’s letter is reproduced. The claims made in it about Forrest are not a single line or two, but shot all through the short booklet; no one could possibly miss them. Why does the SCV (it seems) repudiate these claims now, when the (actual) Sons of Confederate Veterans endorsed them?

And that points to the broader problem for present-day folks who deny Forrest’s involvement with the Klan. Even a cursory examination of early writing about the Klan — and these are explicitly pro-Klan works, defending the organization — shows that they’re almost all uniform in stating Forrest’s role in the group. Real Confederates, and those around them, understood it to be true, and were proud of it. Denial of Forrest’s involvement by Southern heritage groups is much more recent; it’s a revisionist white-washing of his reputation, to make him more (dare I say?) politically correct for a modern audience that is understandably uncomfortable with his association with the Klan.

Believe anything you want; I would only encourage readers to weigh the evidence for themselves, and draw their own, reasoned conclusions.

“I would only encourage readers to weigh the evidence for themselves”

Well, the evidence the prosecuting attorney has submitted.

Well, the evidence the prosecuting attorney has submitted.

…..cliffhanger. I was waiting for the final stroke.

“Of course, second and third hand accounts and newspaper stories must be counted as solid historical truth if it backs up what we **want** to believe.”

…as in the case of those who support the Black Confederate myth.

I grew-up in the 1950’s South. Not from parents or their siblings; but from their parents; I heard that the ORIGINAL Klan was either good, or at least well intended; but that the subsequent Klans were made up of whites, not of “our” class (ie. lower class). It is my impression that subsequent Klans did have difficulty in attracting the upper-class, Southern white class.

I’m not sure if it was the original, or subsequent Klans that saw Klan’s substantial spread outside the traditional South?

One Salisbury,North Carolina, great, great, great grandfather (several sons Confederate vets) had five slaves in the 1850 census, and his future second wife had 15 in the census. Married to each other, in the 1860 census, they had 21; the last being a mulatto infant slave. His second wife divorced him for adultery in a case that went to the North Carolina supreme court. He would get white orphans at the courthouse and apprentice them on his farms until they were adults. He had a child by his white child cook; which let to his subsequent divorce, and two more wives. His grandson, my beloved great grandfather (his father, a captain, died heroically at Fredericksburg), later a Lutheran minister; hated his grandfather and as a child, rolled all over his wheat fields so he could not harvest them. In an old newspaper, I saw this great, great, great grandfather, 1811-1893, was in the “Karolina Konservative Klub”; the first and only time, I’ve seen reference to such.

Another great grandfather was a cavalry Sgt and Lt., and after post war seminary school, an Episcopal priest. I’m very proud of him because long after the war, he and a Wilmington, N.C., Red Cross lady tried long and hard, to get an ex-slave who had long service not in, but with the Confederate army (servant to his officer master) a Confederate pension. Their many letters on the ex-slave’s behalf, are in N.C. State Archives, Raleigh, New Hanover County, Confederate Veterans Applications.

Borderruffian,

Whether you realize it or not, short, one-line replies, with no evidence or fact to refute a point-of-view, speaks volumes.

Neil

As always, great research and presentation. I had a couple of thoughts/questions:

What does it mean that the Klan stood down in 1869? Are we talking just about the Tenn. Klan? While there may have been some sort of acknowledgement of a Klan national structure in the early Reconstruction period, and even exchange of correspondence and materials among local factions (e.g., the boilerplate “constitutions” that appear in the Congressional “KKK” Hearings), I don’t get the sense at all that there was any real national, hierarchical control (as opposed to the 1920 revived Klan). Many, if not most, Regulator groups with the identical goals of overthrowing Republican Reconstruction state governments and asserting white racial supremacy, did not use the Klan name in the late 1860s. Furthermore, the county level groups I’ve looked at in Florida, for example, did not seem to belong to a state-wide, let alone national, organization. And certainly in many places, such as Florida (e.g., Jackson County) or Lousiana (e.g., the Colfax massacre), “Klan”-type operations increased in virulence after 1869.

I anticipate that the Forrest-phile will say “sure you proved he was titular head of the Klan and was instrumental in ending it, but so what? – you didn’t show that Forrest was involved in violence.” As Forrest’s defenders move the goal posts, I expect that they will reply that Forrest was sort of a ceremonial board of directors type too busy on the golf course to be involved in daily operations. You will never convince them otherwise without a smoking gun, bloody shirt and signed confession. I doubt any evidence directly linking Forrest to violence exists: the Klan type groups were structured with multiple levels of authority and control, designed to lend “plausible deniability” to the leaders. [For an example of a Klan-Regulator constitution: http://books.google.com/books?id=hHwUAAAAYAAJ&dq=testimony%20insurrectionary%20florida%20coker&pg=PA157#v=onepage&q&f=false ]

Regulator leaders were often “respectable” professionals, and probably not out night-riding and pulling triggers along with the young chivalry. I’m guessing that Forrest probably didn’t get his hands dirty. Whether he was directing operations and picking targets is impossible to say.

As far as the Memphis speech: that is nothing remarkable. I don’t see it as a change of heart in the least or magnanimous. During Reconstruction, many whites made simlar statements accepting black suffrage – on the implicit condition that blacks must vote the Democratic ticket.

I think that by focusing on Forrest’s role specifically in the Klan you risk falling into a semantic trap set by his defenders. For reasonable people, it should be condemnatory enough to show (as you have proven) that by merely associating himself with and lending his name to the Klan, Forrest endorsed, legitimatized and encouraged Regulator-perpetuated mayhem designed to overthrow elected state governments and reassert white supremacy across the South.

Dan, thanks for your long and thoughtful comment. A few replies:

Great question, that I can’t really answer fully. How hierarchical the Klan of the late 1860s was, and how responsive individual dens (as they were known) were to directives from the top, I’m sure varied quite a bit. It may be that the Klan could stand down (to a greater or lesser degree) in part because its role had been picked up by other, local or regional groups that, by their smaller and more localized nature, were less vulnerable to exposure and attack by the Federal government.

Haven’t heard anything specific from those folks about this post, but I make no claim that Forrest personally committed any acts of violence with the Klan. But neither do I believe he was an uninvolved figurehead; does Forrest really strike you as a hands-off manager kinda guy? Kastler suggests Forrest’s business travels in the period in question were particularly useful for recruiting and organizing purposes, and that seems (to me) the best and most obvious role for someone of his stature.

He didn’t need to.

Yep. Newspaper articles and stories in the Confederate Veteran about former “faithful slaves” often mention that they “always vote the Democratic ticket,” or some such. Voting was not so much an issue, provided whites could be sure African Americans always voted the “right” way.

I try to write reasonable pieces to be read by reasonable people. There’s no point in trying to convince anyone else.

Thanks again for your comments.

If I recall correctly from my time in Knoxville the 1869 date refers to the Tenneessee Klan. More information may be found here (please excuse the shameless plug for a fellow Volunteer) –

http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.php?id=13645

The review you link to certainly doesn’t make it appear as though Forrest was magnanimous or civic-minded in “standing down” the Klan in 1869. To the contrary, it looks like the “choice” was forced on him: “For much of the first half of 1869, the militia compelled the Klan into silence, as it would rather not operate rather than risk open confrontation with the Radical government’s effective military organization.”

Thanks Andy for this analysis. Great stuff!

Thanks. There’s not anything really new, but it’s useful sometimes to spell things out explicitly.

hey there thought this might be of interest:

http://www.studio360.org/2011/dec/09/newt-gingrich-the-candidate-as-novelist/

Thanks. I haven’t said much about this novel because other bloggers, much more knowledgeable about The Crater, have pretty thoroughly debunked it, including Kevin and Brooks. It’s unfortunate that Gingrich — or rather Forstchen who, I’m certain, does the vast majority of actual writing on these novels — took this route. Both men have academic backgrounds in history, but Forstchen is a working, academic professional whose own specialty is the Civil War. I’m sure his collaboration with Gingrich is highly remunerative, but this particular book is, or should be, a bit of an embarrassment.

I don’t read as much historical fiction as I used to, but I remain a fan of the genre. (You can blame C. S. Forester for that.) But nothing kills an historical novel for me faster than when real-life characters are shown doing and saying things that simply never would have happened in real life.

Andy, you might enjoy this article: Parsons, Elaine Frantz. “Midnight Rangers: Costume and Performance in the Reconstruction-Era Ku Klux Klan.” Journal Of American History 92, no. 3 (December 2005): 811-836.

I can send you a pdf if you don’t have access.

Thanks, got it. JSTOR is teh awsum.

Cool. JSTOR rocks! The article adds some interesting context to some of the early histories of the Reconstruction KKK.

Just picked up her new book. Looks really good. Can’t wait to read it.

http://uncpress.unc.edu/browse/book_detail?title_id=3705

Andy, with all the bigotry and uproar being created by the Memphis City Council, I happen across this pathetic essay! Aside from the typos, even if Gen. Nathan B. Forrest may have been in the KKK, you have provided no substantial evidence to support that he was actually in the KKK, except in the minds of those who may have wished that he was in their post war romanticism at the turn of the 19th – 20th century. It’s actually a great piece of evidence of how you and those who agree with you, cherry pick what truth you choose to use in your research, as long as it agrees with your biased way of thinking. Generally anything else relating Confederate histories you term as “Lost Cause Mythology” so what’s the difference in the myths attributed to Gen. Forrest joining the KKK? The only difference is because it suits your intent to distort history to suit the status quo of bigotry you support against Confederate history.

People can read the piece, and its sourcing, and decide for themselves.

I fail to see how certain associations take away from his military genius and the right to be honored. Harry Truman was a Klansman as well, but nobody runs him into the ground. Much like slave owning in the Antebellum era, being a Klan member in the late nineteenth century was not considered out of the norm. Nathan Bedford Forrest was arguably the finest war captain that this country has ever produced. The primary reason that he is so well respected in the south is because of his natural ability to wreak havoc on the battlefield. We defenders of southern military history don’t sit around hi-fiving each other because he was a Klansman. To think that is the case is silliness. I find it ironic that General Forrest is vilified for his pre/post war behavior and yet General Grant is exalted as this great savior of the south and hero to slaves everywhere. The funny part is that he spent his entire presidency making it a point to enslave and/or exterminate the indigenous people of this country. To me that is a bit of a double standard. Nathan Bedford Forrest was good at what he did and should be respected for it.

There is a lot of outright denial among Forrest’s fans that he had any involvement with the Klan. There’s no denying Forrest’s successes on the battlefield, but to solely focus on that, while ignoring the unpalatable aspects of his life, is just silly. Take him or leave him as a whole. Certainly the modern-day Klan reveres him as a foundational leader of their organization.

With Forrest, especially, one phase of his career led to another. He became “Grand Wizard” of the Klan because of his wartime exploits as the “Wizard of the Saddle.” He was able to become a successful military commander because he jumped from Private to Lieutenant Colonel in recognition of his outfitting the regiment at his own expense, using the fortune he’d made as a slave dealer. These are different phases of his life, but completely bound together. One doesn’t happen without the ones that came before.

As for Truman, the evidence that he was inducted as a klansman appears to be shaky, and he certainly wasn’t any sort of leader in that organization, as was Forrest.

“Nathan Bedford Forrest was good at what he did and should be respected for it.”

I understand the Klan is going to be showing their respect for Forrest next Saturday in Memphis. That will be interesting.

Well, I don’t deny he was a Klan leader, so I guess I’ll “take him as a whole”. That is not enough for me not to respect him as an officer. As far as Memphis goes, I will say this: As sitting Commander of the Milton Guards Camp #2214, Sons of Confederate Veterans in Alpharetta Georgia, I nor my camp endorse the actions of the Knights of the Klu Klux Klan, it’s abuse of the Confederate Battle Flag or it’s perversion of the image of General Nathan Bedford Forrest. With that, I would also like to state that for every Klan member that has toted a Confederate Battle Flag, just as many have toted the Stars and Stripes. Shouldn’t we discriminate against all symbols of racism? The fact that Forrest was a slave holder should not take away from his accomplishments. George Washington was a slave holder. Good luck taking his name off of anything. I believe in this day and time, like everyone else, that slavery was wrong. But I think that for far too long it has in itself been abused as a subject and used as a crutch. The sad part about it is that it is disrespectful to the people that actually had to live it.Not every white person who is proud of being southern and respects it’s military leaders is a racist. Most certainly that doesn’t make that sympathetic to the KKK. Nathan Beford Forrest will always have my support, regardless of his other deeds. His KKK actions are no different that what is going on with the City of Memphis right now: racial gerrymandering and baiting. You can’t ask people on one hand to get on their knees, beg forgiveness and pay reparations and then try to throw away the other side. You can’t have it both ways. And so because Forrest briefly led the Klan, now destruction of public property is deemed acceptible by society in Memphis and Selma.

“His KKK actions are no different that what is going on with the City of Memphis right now: racial gerrymandering and baiting.”

I’m sure you believe that.

Also note that I didn’t reference him as being a slave owner, but as a slave trader, which even then was a not-very-respectable line of mercantilism.

“Also note that I didn’t reference him as being a slave owner, but as a slave trader, which even then was a not-very-respectable line of mercantilism”

Point taken. That makes me wonder what runs through the minds of the people today who are descendants of the northern slave traders that accepted slaves at their ports and then sold them to the south. Do they hang thier heads in shame and in turn be ashamed that they are white? Or do they just say, “Hey I can’t relate to being a person who put people in chains, any more than you can relate to being a person in chains”?

Somebody has to answer for it, right?Is it the northerners who obtained and sold them to us, or is it the X amount of people who owned them and may or may not have mistreated them (whose to say, we werent there)? Or is it the Africans who captured their own people like animals and sold them for rum? Where does it end? When all signs of southern culture are gone? Will everyone be satisfied then? The ships from England and Portugal that picked them up in Africa and brought them here?

I think that this is what it really comes down to. Caucasians in this country constantly apologizing and I just dont think I should have to do that? Nor do I think that I should have to be ashamed that I had 13 3X GGF’s who served in the Confederate Army.

I do think that the Memphis situation is race baiting. They supposedly did the name change to unify their citizens and all it appears to have done is make things worse. Why can’t people of all races be allowed to be proud of their ancestors and heroes?

Writing from Memphis.

I’m not sure why you accept the accounts of Klan members at face value. Which sounds better, “I inducted the most brilliant general of the Confederacy into the Klan,” or “I inducted Bob the dude who ran the funeral parlor down the street into the Klan”? There may be truth to these accounts, or there may not, but the self-aggrandizing propaganda of the Klan itself is hardly a neutral source. The Forrest who rode through the night terrifying the forces of Eeeeevil that beset white Southerners after the war is just as much a carefully created myth as the kindly slave trading Forrest who never separated families and was wept over by blacks when he died (I’m quoting comments on my local paper now) is.

The man was head of the Klan, which let’s face it, he was, for a shorter period of time than a presidential term. Then he publicly went on record with his opposition to the Klan. I can’t imagine any sane person thinking he was a saint, but he was a very skilled general, and the evidence is that he ended his life in peace with people of all colors. Why are we at this late date less able to accept that than we were when he was alive?

Thanks for taking time to comment. But instead of asking rhetorical questions like these:

How about instead offering specific reasons why we should disbelieve these accounts, Morton’s in particular. Morton was not just some klansman; he was a very prominent member of the Nashville community. He served as Tennessee Secretary of State, and his wartime record as one of Forrest’s closest and most valued lieutenants was well known. It’s hard to make the argument that Morton needed to make up some false story out of whole cloth — and enlist one of the more popular writers of the day to assist him in such a fraud — in order to puff up his own reputation. Morton seems to me to be about as close and reliable source for this as one is likely to find.

But as with everything else, I encourage my readers to look at the evidence decide for themselves. I find Morton’s (and others’) accounts to be both plausible and persuasive. As I note in the post, through the decade of 1900-1910, while so many former Confederates still lived, there was little dispute or doubt that Forrest had been Grand Wizard of the Klan. Of course, that was also a time when those same former Confederates, and their families, viewed that as a good thing.

I don’t think Mr. Hall will read and respond. Mr. Forrest can be described as a pragmatist. Certainly, one of the reasons he was reputed to be good to his slaves was because they would sell at a better price than if mistreated.

Don’t overlook the humanitarian aspect. 42 of his slaves agreed to ride with him in the war. Only one deserted. People make a great deal about his offer to free his slaves if the war was won. I hope Mr. Hall has not overlooked that he did give them their release papers 18 months before the war ended. He was afraid that he might die in combat and that they would remain slaves.

At the end of the war, twenty of his followers returned home with him. I doubt that every one of the twenty did it because he knew nothing better.

No, I am not a denier that claims he was never a Klansman. What I am communicating is that life and the facts sometimes indicate that a person shouldn’t be pigeon holed without a little more reflection.

When I reflect on Mr. Forrest, I wonder how many people could so fair and such a leader that not one of his slaves made the effort to harm him in combat. I would appreciate Mr. Hall’s thoughts.

Forrest’s dealings with his slaves during the war — much of which is based solely on what he later claimed, and is unverifiable — doesn’t change the fact that he joined the Klan and played an prominent role in it during the first half of Reconstruction.

I do agree that he was a pragmatist. My intent here was not to pigeon-hole or dismiss Forrest, but specifically to lay out the evidence of his involvement with the Klan, which is denied by many, including the editors of the SCV magazine, Confederate Veteran. They ARE deniers. Forrest was quite a complex person, as you will see from some of the other things I’ve written about him.

Thanks for taking time to comment.

Nathan Bedford Forrest is perhaps one of the most polarizing and controversial figures of the Civil War. And I think just rightly so. There are the primary three controversial legacies he has: as a slave trader before the war, Fort Pillow, and his involvement with the Ku Klux Klan. Fort Pillow I think is the most damning of the three. That battle is still debated almost 151 years later and that won’t change anytime soon. Forrest was a very complex person, there is no question about.

What surprises me is that he chose to surrender rather than resort to guerrilla warfare in May of 1865, given his seemingly fierce and fiery personality. That in itself shows that the man was somewhat sensible if he saw the writing on the wall. But what I am intrigued by is that he could have went to Mexico and I’m sure the idea of going to Mexico was very alluring to him. A question that I have asked myself about Forrest is why would you go back home and try to pick up the pieces? Plus there is the fact that if you are Nathan Bedford Forrest in early May 1865, you know that President Lincoln has been assassinated, and that you are essentially at the mercy of the victorious Union. Now you have to play by their rules, and for all Forrest knew he didn’t know what the United States would do him. How could he have known that he might not have been hung for treason or most importantly for Fort Pillow?

Anyway, that is just my own thoughts.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve had the chance to speak to my dad, and uncle about some questions I had regarding Matt Luxton and Bedford Forrest. They were both surprisingly knowledgeable, especially my uncle, who had questioned his family in depth on the subject of ancestry. Anyway, from what I understand, although Forrest didn’t see blacks as equals, he was most certainly very fond of the blacks that served under his command. The courage and loyalty they displayed throughout the war did gain his respect.

Forrest didn’t give a damn what your skin color was in war – if you went against him, he’d kill you. Likewise, if you did your duty and performed honorably in his view, you got his mutual respect.

He freed his 44 slaves (not 42) in December of 1863 for several reasons, the main ones being that he was impressed by their loyalty and service, and also because he knew he might be killed in combat. Half of those did indeed serve in his guard. He himself taught many of them marksmanship and other combat tactics. He also used them as night scouts because their darker skin was an advantage.

If he indeed had armed, black former slaves under his command (They were not termed “soldiers” for legal reasons), this calls into doubt any accusation of Forrest “massacring” black Union soldiers at Fort Pillow strictly because they were black. I think it more likely that his troops continued firing at black Union soldiers (and whites as well) because the Union soldiers were shooting at them. Whether it was confusion, or what, is anyone’s guess. But it was NOT a massacre of blacks BECAUSE they were black.

As to why Forrest went back home to pick up the pieces…

The entire reason Forrest went to war in the first place is because of his love for his home and family! Above all else, his home and family were the most important thing to him. This was actually the sole reason for his involvement with the Klan. Back then, black integration was not the issue – Northern Carpetbaggers and injustices done by occupying Union troops WERE. Forrest viewed the Klan as a way to protect his home and people – not from blacks – but from Northerners who were taking advantage of a war-ravaged South.

Incidentally, my 2nd great grandpa Matt Luxton DID kill a Carpetbagger and uncle Bedford moved him, and his family to Texas, under the protection of Sam Houston. I’m continuing to learn what I can from family, and documenting it where and when I can. I hope this helps answer some questions.

That sounds like a lot of apologist stuff right there so I am not even going to go there. But I will say this, the idea of going Mexico was alluring to Forrest (I imagine) and as I said before he could not have known that he wouldn’t be hung. Just like Robert E. Lee before he surrendered at Appomattox, I’m sure Lee was well aware of what happened to rebels, you hang rebels and Lee could not have known that he wasn’t going to be put on trial or hung in that instance either. Plus what is there a home to go back to? The world that Forrest knew before the Civil War was gone, why go back home and try to pick up the pieces? Plus the KKK and all of these other groups did what they could to undermine Reconstruction. The Klan in Tennessee wanted to fight back against Governor William Brownlow and his policies in “self-defense.” I would say that what happens during Reconstruction with the Ku Klux Klan is a militant continuation of the Civil War. Yes there were carpetbaggers and those who tried to exploit the South and try to make a profit after the war ended, but there were also scalawags like James Longstreet and John S. Mosby. Longstreet after the war aligned himself with the Republican Party and endorsed Reconstruction, and Mosby supported Ulysses S. Grant for President in 1868.

You can’t change the fact that Nathan Bedford Forrest shall remain one of the most controversial and polarizing figures of the Civil War. There is no way around it, those three main legacies shall haunt him. And I don’t know what to make of the fact that he did accept a bouquet of flowers from an African American woman while giving a speech to an audience in New York after the war, but it still doesn’t change the facts. If he reflected and changed at the end of his life, well then good for him. But I have yet to find anything that Forrest wrote before he died in 1877 where he says anything to support that. Now Jo Shelby is a very interesting figure in that he remained defiant after Lee surrendered and went south into Mexico to offer a quixotic proposal to Maximilian, but he refused. And Shelby came back and later became a U.S. Marshal and he never applied for a pardon, but what I find fascinating is that near the end of his life, Shelby said that, “John Brown was right.” And I think that speaks volumes about Shelby. He was someone who went from being a border ruffian to a Confederate who was unwilling to surrender to saying that John Brown (another controversial figure) was right. That’s just astounding to me.

Dwayne;

I think that you are sincere in your beliefs in regards to your family, however if your 2nd great grandfather did kill a Carpetbagger after the war it would be impossible for him to be protected by Sam Houston, because Houston died in 1863. I doubt very much that Houston would protect any confederate because Sam was a staunch Unionist.

Get your fucking facts straight before you slander someones name.

You have a nice day, friend.

Mr. Hall…

I have been in a conversation with a few people…some close friends and some on-line strangers about the call to have the Confederate flag and various other symbols of the Confederate removed from state property. My position in this was (and is) that I thought that state property was inappropriate for the Confederate flag but I thought that the call to remove certain statues was much more interesting…as in “Where do you draw the line?”.

I offered Nathan Bedford Forrest as a slam dunk example of someone who should not receive state honors in this modern day world.

Thanks for messing up my neat little picture of him!

Nicely written. I plan to read it again a few times to really absorb the details.

Thanks!

Forrest is an interesting and complicated character, for sure.

I do not wish to debate whether or not Nathan Bedford Forrest was part of the Klan, or was ever “chosen” as their Grand Wizard, and commend Andy for his thorough research, and although there is certainly room for debate on the accuracies of accounts, I wish to instead point out, that this figure has been forsaken for what could be spun positively instead of negatively. Case in point being, that somebody of his prominence, who later, goes completely against those beliefs, even at the sneers and judgments of his fellow white Southern neighbors, to stand for racial equality in a still very emotionally charged period, only 10 years after the civil war ended, where 1/3 of the Southern male population lost their life, for a cause made in vain, is quite something to be recognized. And I feel like this is where the true emphasis of his historical importance of NBF should be placed. We should not ignore his past. We should certainly not sweep it under a rug, but I feel like all sides, and the whole story should be told. And what about everybody else in the South who wasn’t famous but was either supporting the KKK, or even just standing by watching it and doing nothing? Wasn’t it Martin Luther King who said, “He who passively accepts evil is as much involved in it as he who helps to perpetrate it.”? So how is not every other person in Tennessee at the time of the KKKs organization, who stood by and did nothing, not as condemned, if not more so than NBF, who later attempted to disband it once it became violent? In fact, Congress recognized that, noting that when it became violent, that due to NBF’s power and influence, and having morals, he was able to persuade others to disband it. (or at least he attempted to). I find it strange that instead of finding this to be a positive thing, it is used against him to target him as a racist klan leader, as why would anybody have any influence to stop something unless they were apart of it. However, that is besides the point, regardless of how much truth there is in that, wasn’t St. Paul of Tsarsus on his way to Constantinople to fight and suppress Christian uprisings, when he then became a Christian himself? Even semi-Bible-literate people know, St. Paul then later became one of the most revered symbols of Christianity. I am not in anyway trying to draw a comparison of St. Paul’s overall personage with that of NBF, but I am only drawing this analysis to illustrate that sometimes, those who stood for one thing, are not only fully capable of standing for the opposite position later on, but can be a very powerful driving force doing so. Furthermore, by standing up and making his speech in 1875, emphasizing racial equality, he stood up and said things very few other white Southerns at the time would ever consider doing, either because they didn’t feel that way, or for fear of being ostracized by their fellow neighbors. So he put himself out on a real limb, considering the context of this still very emotionally charged time period, and clearly did something worth being recognized for today. But yet, all he is recognized for today, appears to be speculative debates regarding whether or not he was part of the KKK, or was named its leader, (btw, being chosen as the leader and accepting to be a leader are two different things). And then what I find appalling, as a human being, that there are people relying on one side being true on a highly debated position, that said reliance on one side of the argument, should allow his human remains to be dug up and removed from its resting place, because he is being demonized for it 150 years later. Let the dead rest. Take his statue down if you must, but let him sleep in peace. Hopefully, one day instead of trying to always emphasize evils and act out of a sort of revenge for those evils, people can someday recognize whatever he may once have been, his repentance and positive changes and contributions, and use that to try encourage further positive change by others. We are all Americans after all, and we all stand under one flag… which is the same thing NBF said to his soldiers in his farewell speech, in May of 1865. Happy 4th everyone. Sorry for the novel. Thanks if you read the whole thing.

Curious. We’re to take Forrest’s 1871 testimony as self-serving lies while treating Morton and Crowe’s legend building forty years after the fact as gospel. Did it ever occur to you that with the passage of time and the growth of nostalgia that a long dead Forrest might make a more convenient tentpole for the foundation of the Second Klan even if he hadn’t been one for the first?

And then we have a parade of false dichotomy. Forrest must either be the Klan’s enemy or friend. He must either be the Klan’s commander or impotent. He must be up to his neck in Klan regalia and activity or ignorant of it entirely. He must be in league with his former comrades or publicly estranged from them. He must love the carpet-bagger or be party to the outrages of any hair-brained outfit calling itself the Klan.

Finally, why do you assume that a slave trader must have personal animosity and disdain for his chattels? A trader was not a planter; he was not a product of polite society maintaining a healthy distance from his product by chains of intermediaries. He dealt with Black slaves up close and personally, which could inspire considerable cruelty and–even or–considerable respect for their humanity. In Forrest’s case, the story depends on who you ask.

Of course Nathan Bedford Forrest was in the Klan… Forrest Gump said so in the movie!

All joking aside, I’ve always heard that he was both a Civil War General and a Ku Klux Klan leader. This is nothing new. But I’d like to know when the denying started!

This blog is not conducting a criminal prosecution of Forrest, but rather a civil trial (civil as in civility). So the preponderance of evidence is the standard to use and you’ve clearly met that to anyone who isn’t trying to change History to defend the indefensible.

Forrest was a fascinating figure. He wasn’t part of the Southern political class or military class, but came up from the ranks in both areas. He probably had less interaction with Northerners than people like Davis, who had a lot of doughface friends like Pierce, or Lee who knew all the Northern West Pointers well. This would have made him likely to want to continue surreptitiously resisting Northern influence in the South.

I came here on an internet sleuth – I was certain that NBF’s address to the “Pole Bearers” was an internet hoax, and it turns out not to be the case. It was real, got it. But why? I don’t understand how a man so brutally anti-black could have publicly disavowed his former world view, and pardon me, I don’t think you’ve clarified it here.

Why? How? This absolutely mystifies me.

I will eventually write on this in more detail, but the gist of it is this — Forrest gave his speech at the end of Reconstruction in Tennessee, when the Democrats had regained the reins of political power. They (and Forrest) understood that they weren’t rolling back things like the 14th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, so they were adjusting to the new political and cultural reality as it was in Tennessee in the mid 1870s. Very specifically, the Pole Bearers had recently been implicated in some killings, and Memphis was at that moment ripe for another flash of large-scale racial violence like it had seen several years before. (The Pole Bearers are sometimes described as a “civil rights” organization, but that’s not correct in the modern sense; they were a mutual aid and self-defense group.) Forrest’s speech was an effort, an outreach, to tamp that down, to pour oil on troubled waters. You know the phrase, “only Nixon could go to China?” That’s because Nixon have a reputation from the 1950s of being a hard-line anticommunist, so it had to be Nixon who broke the barrier and extended a hand to Red China. Same deal with Forrest and Pole Bearers. Forrest’s message to the African American community of Memphis was, in essence, be good citizens, work hard, and don’t get uppity.

It’s true that Forrest mellowed some in his later years, as his health began to fail and he began to feel his own mortality. I do believe he began to be more pragmatic in his views and his approach. But the idea that Forrest was some sort of civil rights visionary, or that he had some epiphany about the greater brotherhood of men of all races is ludicrous. His Pole Bearers speech is one that was unique to that specific time (July 1875) and that specific place (Memphis). Change either of those variables, and it never would’ve happened.

Also note that a fair number of his fellow Confederate veterans shit their butternut drawers when they heard about it.

From what I read Gen, Forrest was a bad person , but I believe its all hear say , he said , she said, it amount to

black hates the south, and most people up north do also when it come to true history,

There’s more than ample evidence that Forrest was a member of the Ku Klux Klan almost from its founding. It’s attested to by many people who had first-hand knowledge of it, like Morton. His major biographers (e.g., Hurst) agree on that point.

The problem with the historical record is that it makes no distinction of the early and later Ku Klux Klan. It fails to understand the origins of the Klan and its original activities and purpose, versus what it became, and the reason Forrest resigned. The Klan is falsely portrayed as only sheet-wearing horsemen terrorizing “innocent” Blacks (who were seldom innocent). Forrest believed that the original purpose of the Klan, which was eminently justifiable, considering the treatment being meted out on Southerners by Northern carpetbaggers and Black Union soldiers, had been accomplished and the Klan was becoming too violent, the reason he left and also the reason he tried to disband the organization. Forrest has no reason to apologize for his connection withthe Klan, but try explaining that to a hostile Yankee-dominated Congress. Good luck – they still believed they were justified in murdering over 300,000 Southerners so they could protect their Northern economy from the Confederacy’s free market trading laws. Of course, they changed that purpose into the non-existent purpose of freeing those slaves, after having voted to pass a Constitutional endment which would have guaranted the continued existence of slavery in the Old South “forever” and would be irrevocable. But then, Yankee-authored and published Civil War histories never even remotely accurate about their illegal and unprovoked attack on the Confederate States of America, the only true demoncracy of that time in America.

The Reconstruction Era Klan and similar paramilitary groups were terrorist organizations that used violence (and the threat of violence) to achieve their political and social objectives. Period, full stop. Thanks for stopping by.

Thank you for an interesting article.

I think it’s true, as you say. Mr Forrest was a complicated man.

I do hope he genuinely repented of his earlier views at the end of his life.

Lots of folks believe he did. There was a book devoted to that argument published a few years back.