Walter E. Williams Polishes the Turd on Tariffs

Canal boats (foreground) and blue-water sailing ships crowd the waterfront near South Street in lower Manhattan in this 1858 view by Franklin White of Lancaster, New Hampshire. In that year, customs duties collected at the Port of New York alone provided nearly half of all federal revenue. When foreign trade rebounded the next year after the Panic of 1857, customs duties collected at the Port of New York accounted for almost two-thirds of federal revenue. From Johnson and Lightfoot, Maritime New York in Nineteenth-Century Photographs.

The other day, George Mason University economist Walter E. Williams published an opinion piece in the Washington Examiner, asking in the title, “was the Civil War about tariff revenue?” Like many of his columns that deal with that conflict, he tosses in all sorts of obfuscatory boilerplate about Lincoln not liking black folks much, how the Emancipation Proclamation didn’t actually free all the slaves, and how Lincoln, more than a decade before the war began, had made some general comments about the inherent right of revolution. Williams doesn’t get around to discussing, you know, tariff revenue, until the very end, more than nine-tenths of the way through the 657-word piece, when he says (my emphasis),

![]()

![]()

I want to focus on that line about Southern ports paying 75% of import tariffs, because it’s the core of his entire argument. He’s playing an classic trick, throwing out some impressive factoid, and then asking a rhetorical question based on it, that seemingly has an obvious answer. The problem is that, in this case, his devastating “fact” — “Southern ports paid 75 percent of tariffs in 1859” — isn’t even close to being true.

The first red flag here is that annual tariff data was not collected and reported by the Treasury Department based on calendar years, but by fiscal years that ran from July 1 to June 30. So when Williams says “in 1859,” it’s unclear whether he’s talking about the reporting year that ended in 1859 (FY 1859), or the reporting year that began in 1859 (FY 1860). That’s a revealing slip-up, but it’s also one that doesn’t matter, because the claim is demonstrably untrue for both fiscal years, and so for the calendar year of 1859, as well.

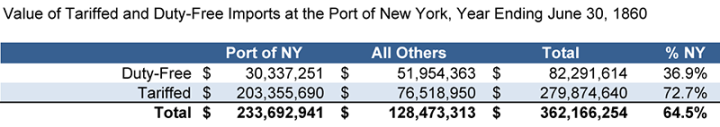

Data for imports and tariffs collected for the year just prior to secession (July 1, 1859 to June 30, 1860, inclusive) is provided in the Annual Report of the Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York, for the Year 1860-61 (New York: John Amerman, 1861), 57-66. I’ve uploaded a PDF copy of the relevant pages here. The first two pages include imports that were not tariffed; in case anyone was wondering, manures and guano were duty-free.

In summary, during that year the Port of New York took in $233.7M, of which $203.4M were subject to tariffs ranging from 4 to 30%. During that same period, all other U.S. ports combined received $128.5M in imports, of which $76.5M was subject to tariff. So the Port of New York, by itself, handled almost two-thirds (64.5%) of the value of all U.S. imports, and almost three-quarters (72.7%) of the value of all tariffed imports:

![]()

![]()

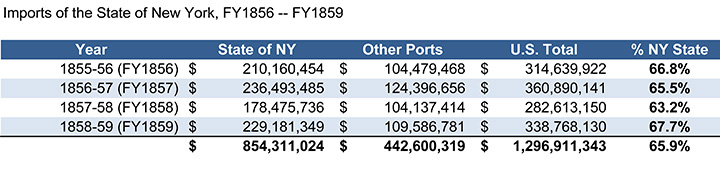

What about earlier years? The previous year’s report from the New York State Chamber of Commerce carries a table (p. 2) that breaks out imports clearing customs in all of New York State for the previous four fiscal years:

![]()

![]()

A glance at these numbers makes clear that in spite of some year-to-year variation in import volumes — there was an economic crash in 1857 — the share of imports coming into New York remained remarkably stable, at around two-thirds of all imports coming into the United States. (And this isn’t even including other major ports like Boston and Philadelphia.)

What about customs revenues, specifically? The Chamber of Commerce from 1860 reports — on the very first page — customs revenue for Port of New York for 1859 at $38,834,212, or about 63.5% of the $61.1M in federal revenue that year. The Port of New York, alone, accounted for nearly two-thirds of U.S. Government revenue in 1859. Williams’ assertion that “Southern ports paid 75 percent of tariffs in 1859” isn’t a case of “lying with statistics,” because the statistics don’t actually say anything remotely like that. It’s a case of lying, period.

So where does this made-up-from-whole-cloth assertion come from? Williams’ column has been splattered all over the Internet in the last few days, no doubt because it seemingly affirms modern cultural/political fears about big gubmint avarice. But the idea that Lincoln refused to accede to the Southern states’ secession because they represented the large majority of federal government’s revenue has been percolating around for a while. Thomas DiLorenzo — who Williams cites in the first graf of the piece — made a related and equally implausible claim in his 2002 book, (The Real Lincoln, pp. 125-26) that “in 1860 the Southern states were paying in excess of 80 percent of all tariffs. . . .” People who’d looked at the actual numbers, including friend-of-this-blog Jim Epperson, called him out on that claim, which DiLorenzo eventually (and quietly) revised in his most recent edition to a somewhat more vague “were paying the Lion’s share of all tariffs.” DiLorenzo, not surprisingly, provides no citation to back this claim. But it’s and old turd of a notion that’s been around a long time, that Walter Williams has pulled out, polished off, and given new life on the interwebs.

(DiLorenzo’s wording is a little different, saying that the “Southern states” were paying tariffs. It’s a strange construction, given that the states weren’t paying tariffs at all, and the tariffs were paid by the merchants doing the importing — who were generally Northerners. Even if DiLorenzo were to argue that it was the end-of-the-line consumer who “paid” the tarfiff through higher costs for goods, it’s a claim that defies credulity, as it would require the eleven states that ultimately seceded, with less than a third of the nation’s population, to be consuming more than four-fifths of all the tariffed good brought into the entire county. It’s a ludicrous notion, which is probably why DiLorenzo doesn’t even pretend to offer a source for it.)

Williams and DiLorenzo have both made a good living writing books and essays and giving speeches that are full of half-truths, selective quotes, and (as in this case) outright fabrications, all directed to a narrow but extremely-loyal audience of people who are primed to believe anything bad about the federal government (then or now). Both men hold endowed academic appointments, which means they cost their respective institutions relatively little, and in return are free of heavy teaching loads and the imperative of generating peer-reviewed publications that stalk most faculty members through much of their careers. Fair enough, but Williams’ assertion that “Southern ports paid 75 percent of tariffs” is surely in a league by itself. On its face it strains credulity; one needs only a basic understanding of American history to know how overwhelmingly the Northern Atlantic states and New England dominated this country’s maritime trade through the end of the 19th century. True Southrons™ often cite the heavy involvement of Northern shipping interests in the transatlantic slave trade, but that’s a selective and self-serving focus; that same region overwhelmingly dominated every other aspect of American maritime enterprise, from shipbuilding to whaling to the China trade to the nascent practice of marine engineering.

Williams surely knows this, and knows his assertion about the share of import tariffs paid through Southern ports is preposterous. If he doesn’t know it, he’s unworthy of his credentials, and if he does and asserts it anyway because that’s what his audience wants to hear, then he’s a charlatan on the order of someone like David Barton. I really can’t imagine what’s worse — the idea that he doesn’t actually know he’s wrong, or the idea that he doesn’t give a damn.

____________

UPDATE, February 25: In the comments, Craig Swain points out that he covered this same ground two years ago, over at Robert Moore’s place. I owe Craig an apology, because I not only read that post of his at the time, I also commented on it. I’d completely forgotten about that, at least consciously. Craig does a particularly good job of showing how those same tariff laws, which supposedly were so beneficial to Northern industries, also protected Southerners’ production of things like cotton, tobacco and sugar from competition from overseas.

Given the way spurious claims about tariffs are made over and over again by folks like Williams, naturally they’ve been exposed by others before. But it’s hard to use evidence to counter a belief that’s not based on evidence to begin with.

____________

37 comments