“This is rather an onerous position in the company”

William Watson (b. 1826) was a Scotsman, a Clydesider, who emigrated to the West Indies in 1845 and worked there as an engineer and sometimes-ship-captain. About 1850 he emigrated again to Louisiana, where he worked as an engineer and eventually became part-owner in a sawmill and wood business, with additional business interests in selling coal and steamboat operations. Watson was opposed to the secession of the Southern states, but as a member of the local militia unit in Baton Rouge, he enlisted in the Confederate Army for a one-year term with his company, the Pelican Rifles, which eventually became Company K, 3rd Louisiana Infantry. He fought in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. At the end of his one-year enlistment, he had the opportunity to accept a commission as an officer, but declined as it would require him to renounce his British citizenship. He was discharged in July 1862 but, upon discovering he had lost all his property with the Union occupation of Baton Rouge, he went back to revisit his regiment in the field and got caught up in the Battle of Corinth. In that action he was hit in the leg by a spent round, a wound that, he later said, “although painful, was not dangerous, if I could get timely relief.” After the Confederates fell back, he was picked up on the field by Federal medical personnel, treated at a field hospital, and soon paroled through the efforts of a fellow Scot on General Rosecrans’ staff.

William Watson (b. 1826) was a Scotsman, a Clydesider, who emigrated to the West Indies in 1845 and worked there as an engineer and sometimes-ship-captain. About 1850 he emigrated again to Louisiana, where he worked as an engineer and eventually became part-owner in a sawmill and wood business, with additional business interests in selling coal and steamboat operations. Watson was opposed to the secession of the Southern states, but as a member of the local militia unit in Baton Rouge, he enlisted in the Confederate Army for a one-year term with his company, the Pelican Rifles, which eventually became Company K, 3rd Louisiana Infantry. He fought in the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. At the end of his one-year enlistment, he had the opportunity to accept a commission as an officer, but declined as it would require him to renounce his British citizenship. He was discharged in July 1862 but, upon discovering he had lost all his property with the Union occupation of Baton Rouge, he went back to revisit his regiment in the field and got caught up in the Battle of Corinth. In that action he was hit in the leg by a spent round, a wound that, he later said, “although painful, was not dangerous, if I could get timely relief.” After the Confederates fell back, he was picked up on the field by Federal medical personnel, treated at a field hospital, and soon paroled through the efforts of a fellow Scot on General Rosecrans’ staff.

More than twenty years later, Watson wrote two extensive, detailed first-person accounts of his wartime activities, Life in the Confederate Army; Being the Observations and Experiences of an Alien in the South During the American Civil War, and The Civil War Adventures of a Blockade Runner. Here, in the first book, Watson describes his appointment as orderly sergeant of the Pelican Rifles, and the duties that went with the post.

The standard complement of officers and non-commissioned officers for a company of infantry was: one captain, two lieutenants, one orderly-sergeant, four duty-sergeants, and four corporals. It had always been the rule among volunteer companies for the members of the company to elect their officers, but now by the” army regulations” it was pointed out, that although the members of the company might still elect their officers, yet no appointment would be continued unless the candidate passed an examination, and was found duly qualified and approved of by the brigade commander. This, however, did not apply to officers who held their appointments before the company was mustered into service.

It so happened that our orderly sergeant was the son of the captain, and as the latter carried on an extensive business, it was necessary that he should remain at home to attend to the business; he therefore had not volunteered, but he had continued to act, and had accompanied the company thus far, but as now about to take his leave and return home. The office of orderly-sergeant was therefore vacant. In the American service this is rather an onerous position in the company, and I who was then third-duty-sergeant was selected for the post, and was examined for competency before a board of officers. I passed satisfactorily, but in the course of the examination it came out that I was an alien, and not a citizen. This was against me, but after some consultation it was considered that as the office was not commissioned I might pass, and the appointment was approved. I was, however, given to understand, that I could attain no higher position, and could not hold a commission until I became a citizen; and they advised me to get the preliminaries done at once, as it would take some time to consummate it, unless a special dispensation of the rules was granted.

They then handed me a copy of the “army regulations” for my guidance as orderly-sergeant, and specially directed my attention to a clause which read thus: “No foreigner shall hold any office under the United States Government, either by commission or otherwise, unless he be a citizen of the United States;” the same regulations being adapted for the Confederate States, with the simple alteration of the word “United” being obliterated, and the word “Confederate” substituted.

I had already determined that I would never forswear or renounce my allegiance to Queen Victoria, to become a citizen or subject of any foreign power, nor would a commission in the Confederate service now tempt me. I had volunteered my services for one year, and that I would fulfill as far as lay in my power. I will now give a slight description of the duties of an orderly-sergeant as it was in the United States service at that time.

He held the rank of sergeant-major,* his pay was equal to one-and-a-half that of the first duty-sergeant. He was the general executive officer of the company. He was secretary of the company, and was allowed a clerk. He went on no special detachments, or guard duty, except in cases of emergency. He kept the roll-book, and all other books, papers or accounts of the company. He was accountable for the men present or absent. He returned every morning to the adjutant a report of the state and effective force of his company.

He made out all requisitions for rations, ammunition, arms, or camp equipage, and all other requirements. He had charge of all the company property, and reported on its condition. He inspected the tents and company camp ground, and saw that it was properly formed and ditched, and inspected the sanitary arrangements. His signature must be the first, and followed by that of the captain, on all company requisitions and reports. He called the roll at reveille, and noted absentees and delinquents, punished for slight offences, and reported more serious offences. He gave certificates to men who wished to apply for leave of absence. He detailed all men for guard, and detachments for special service, and appointed police guards for the day. He reported the sick to the surgeon, and saw them attended to. He marched up to the colour line, and handed over to the adjutant all details for special service and guard duty. He drilled all squads, and the company in absence of the commissioned officers. He took his place on the right of the company, and acted as guide. He went to the front and centre at parade and heard the orders read. When in front of the enemy, he was generally informed privately of the programme, and of the movements to be made. While the duty sergeants were designated by their respective names as Sergeant T. or Sergeant H., he was designated as the Sergeant, and was regarded as the ruling power of the company when on active service. With all these duties to perform, it may be imagined that I had sufficient to keep me from repining.

______________________

* Watson’s service record confirms that his rank was first sergeant, and his pay as $20 per month.

“Neither courier nor expressman will be permitted to go up by the trains”

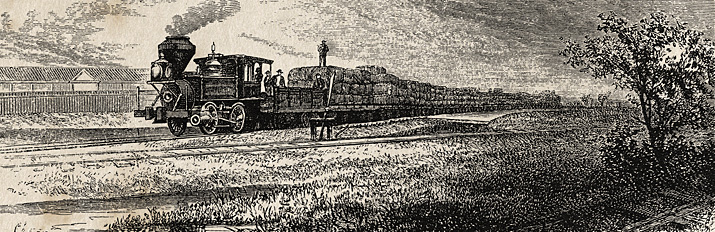

At the height of the yellow fever outbreak in Galveston in September 1864, General Walker issued orders regarding travel by rail, as an adjunct to the quarantine he’d ordered six days previously.

Head Quarters, District of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona

Houston, Sept. 22, 1864Brig. Genl J. M. Hawes,

GalvestonTrains will leave Galveston hereafter on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

Neither courier nor expressman will be permitted to go up by the trains, the mails will be delivered to the Conductor, who will also hand the mail from Houston.

When trains are about leaving Galveston, have a guard at the depot to prevent unauthorized persons from getting on board. Trains will also be overhauled at the bridge [connecting Galveston Island to the mainland] and persons without passes taken off.

Captain Smith of the Zephine is permitted to come to Houston upon the condition of changing his clothes at Virginia Point.

J. G. Walker

Maj Genl Cmdg

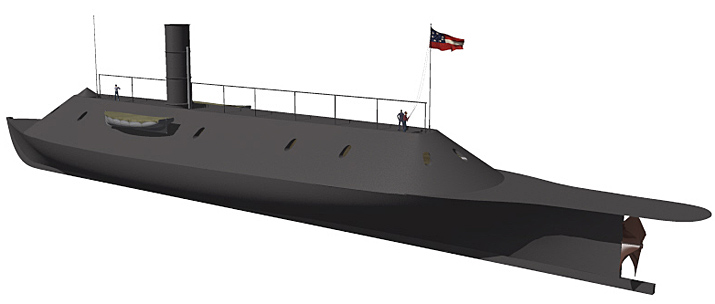

Zephine was a blockade runner from Havana that had arrived on about September 10. She was a large, iron-hulled sidewheel steamer built by Holland and Hollingsworth of Wilmington, Delaware earlier that year. According to Stephen Wise’ Lifeline of the Confederacy, Zephine carried out over a thousand bales of cotton on her return to Havana, turning a profit of more than $300,000 in gold — enough to pay for the ship, crews’ wages and the inbound cargo in one round voyage.

_________________

Images: Cotton train in Texas in the 1870s; Walker order via Footnote.com.

Do Not Read This Post

Instead, force-march your corps over to Mysteries and Conundrums, to see the first installment of Mac Wyckoff’s analysis of the Richard Kirkland story. If you’ve followed that blog’s recent review posts on the fate of Stonewall Jackson’s arm (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3), you already know you’re in for a worthwhile read.

What, you’re still here? Be gone, already!

Camps Las Moras, C.S.A.

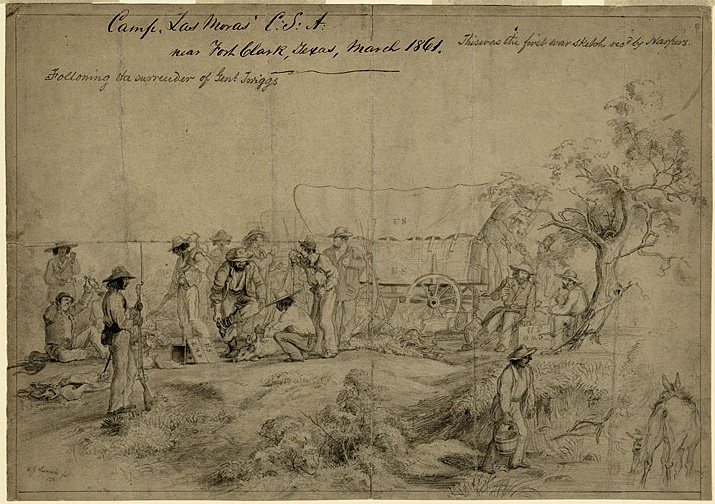

Harper’s Weekly, June 15, 1861:

We publish on page 375 a picture of a REBEL ENCAMPMENT IN TEXAS, from a sketch sent us by a gentleman whose secessionist views are beyond question. He writes : After the surrender of San Antonio by General Twiggs, State troops were organized in order to take possession of the forts occupied by the U.S. Army. The above is a true picture of a portion of said State troops encamping on the Las Moras, near Fort Clark, on their way to the upper posts (Hudson, Lancaster, and Davis). The picture ought to speak for itself. We need not remind that the “U. S’s” and the ” Q. M. D.’s” imply their former owners; and add, furthermore, that no white man in these diggins will be astonished to see the poor Mexicans do all the “hauling of wood and drawing of water,” the Dons being engaged in smoking cigarritos, eating sardines, drinking Pat’s “favorite,” superintending the killing of a stray pig, etc., etc. A lineal descendant of Montezuma stands sentinel, by order No. 1 : “Put none but true Southerners on guard tonight !”

Las Moras was located in West Texas, near present-day Brackettville. The upper image, from March 1861, is labeled (upper right) as “the first war sketch rec’d by Harpers” (Library of Congress). The image below is the sketch as published in June (via SonoftheSouth.net):

Blanket Boats

Bloggers sometimes follow a meandering, free-association path in their posting — I do, anyway. Case in point: Craig Swain of To the Sound of the Guns blog commented on this post of mine, which led me to read this post on his blog, which in turn led me to poke around the Library of Congress image holdings related to Civil War artillery, which in turn led me to this image (above), captioned as “raft of blanket boats ferrying field artillery and soldiers across the Potomac River.” The term “blanket boat” was new to me so that, in turn, led to further digging.

None other than Herman Haupt (via Google Books) does the knowledge:

In connection with the subject of boats and bridges, it is proper to describe a very simple, practical, and highly useful plan, for crossing streams by means of boats, constructed of a single rubber blanket, capable of carrying a soldier, knapsack, arms, and accoutrements, with only 4 inches of displacement. The size of some of the ordinary blankets is 6 feet long, and 4 feet 9 inches wide, but 7 feet by 5 feet would be preferable. If the height of the boat be made 1 foot, the length will be 4 feet, and the width 2 feet 9 inches, so as to be completely covered by the blanket. The frame may be made of round sticks, 1 inch and 1½ inch in diameter, in the following manner. . . .

One of these boats having a horizontal area of 11 square feet, would require 687 pounds to sink it 1 foot, and the average weight of a man would displace less than 4 inches.

In using these boats, it will be convenient to lash several together, side by side, upon which soldiers can be transported; the float can be paddled, or a rope may be stretched across, supported by floats, and the men can pull themselves across.

If used for cavalry, some of the men can hold the bridles of the horses, while the others can pull, paddle, or pole across the stream, the saddles being placed in the boats.

The frames are abandoned, or used for fuel, when the army has crossed over.

Several of these boats lashed together, and covered with poles, would form a raft, on which wagons could be carried over; but for artillery, rafts of wagon-bodies, or something possessing greater powers of flotation, should be employed.

Where the timber is of large size, and round sticks for making the boat-frames cannot be procured, the material may be obtained by splitting large straight-grained timber; and it is even preferable to the round sticks. . . .

Ferry of Blanket Boats. — A ferry may be made of blanket boats in the following manner:

Rafts are formed by lashing together a number of boats, and covering them with boards, or poles, if boards cannot be procured. Twenty-five boats would make a raft 14 feet wide and 20 feet long, with power of flotation at 6 inches immersion of over 8,000 lbs; fifty men could easily be carried in one of these rafts, with guns and knapsacks.

Two ropes are stretched across the river, and the men on the rafts pull themselves over rapidly, hand over hand, one rope being used for the loaded rafts, and the other to return the empty ones.

The rafts can follow each other in rapid succession, leaving intervals not exceeding the length of a raft.

The whole number of rafts should be three times as many as would make a train reaching entirely across the stream, with the proper intervals. This will allow a reserve sufficient to insure a constant stream going and returning.

If the stream should be 600 feet wide, the number of rafts would be forty-five; the number crossing at one time loaded would be fifteen. At a rate of movement of 2 miles per hour, the time required to cross would be about 4 minutes; and the number of men thrown across in one hour, would be about 10,000. The forty-five rafts would require 1,125 boats which could be made by a single regiment of instructed engineer troops in an hour, if materials had been previously prepared.

One of these blanket boats would weigh less than fifty pounds; a man could carry one for a distance of several miles without inconvenience; and with the help of 1,000 feet of rope, a corps of ten thousand men could approach a stream at a point where the enemy did not anticipate any attempt at crossing, and, in two hours, could be landed on the opposite side, ready for an advance, leaving a body of engineer troops to prepare for the possible contingency of a retreat, by constructing pontoon or trestle bridges, if necessary. Even in retreat, the rafts would afford great facilities for crossing, if covered by good batteries on the shore; but without bridges, it would be difficult to save the artillery.

Where surprises are to be attempted, such facilities for crossing large streams, without designating the point by previous preparations, would prove invaluable.

They might prove very useful in cavalry expeditions, to operate against the communications of an enemy.

If the material for the frames of the blanket boats should be transported in wagons, they would, in that case, be prepared in advance, of dry lumber, and the materials for one frame would weigh but fifteen pounds. An ordinary wagon would carry material enough for two hundred boats.

Haupt’s description strikes me as hopelessly optimistic as to how quickly and easily these DIY boats could be assembled and deployed by an army in the field, but the principle is sound enough. The raft shown above employs 30 boats which, if they match Haupt’s standard measurements, would have a lifting capacity of 10,305 lbs. at six inches’ immersion.

So — how often were blanket boats used in actual operations? Did they ever develop much beyond the testing phase, as seems to be the case in the photo?

The Wicked Dr. Blackburn

I’ve just finished Andrew McIlwaine Bell’s Mosquito Soldiers: Malaria, Yellow Fever and the Course of the American Civil War. It’s a wonderful book, and while I’ve had a good idea of how the spread of yellow fever affected events on the Texas coast, it’s revealing to see how widespread the problem was and how fundamentally it shaped operations during the war. Early in the war, Winfield Scott had cautioned against hasty and ill-prepared operations in the South, and instead urged General McClellan to wait for “the return of frosts to kill the virus of malignant fevers below Memphis.” In this, as so much else, the old general proved prescient.

One of the great stories Bell reveals is the Confederacy’s attempted use of biological warfare — specifically yellow fever — against the North.

Luke Pryor Blackburn (left; 1816-1887) was a Kentucky physician who had gained an international reputation as an expert on the treatment of yellow fever. Although no one, including Blackburn, recognized mosquitoes as the vector by which the disease spread, by the early 1860s Blackburn was famous for his knowledge and understanding of the disease. With the outbreak of the war, Blackburn held a number of offices supporting the Confederate government before, in late 1863, he relocated to neutral Canada to help in making arrangements for blockade runners.

Luke Pryor Blackburn (left; 1816-1887) was a Kentucky physician who had gained an international reputation as an expert on the treatment of yellow fever. Although no one, including Blackburn, recognized mosquitoes as the vector by which the disease spread, by the early 1860s Blackburn was famous for his knowledge and understanding of the disease. With the outbreak of the war, Blackburn held a number of offices supporting the Confederate government before, in late 1863, he relocated to neutral Canada to help in making arrangements for blockade runners.

Like another well-known native of a border state, John Wilkes Booth, Blackburn harbored a deep and smoldering hatred for the Union cause and, in particular, Abraham Lincoln. Like Booth, Blackburn never quite managed to find a way to get into a gray uniform during four long years of hard war. And like Booth, Blackburn would channel his anger and intellect into an improbable scheme that would, in his own mind at least, topple the Union government and its president.

In December 1863 Blackburn met in Toronto with Godfrey Hyams, an English-born Arkansas cobbler who’d skeddadled to Canada to get out of the way of the war, but who subsequently decided he needed to do something more substantial to support his adopted home. Like Blackburn, Hyams seems not to have been interested in military service, so the two Southern expats instead cooked up a plot to spread yellow fever throughout Northern cities, where the disease was less common than in the South, and where they believed the population would be far more vulnerable to it. Now all the pair needed was an epidemic, from which they could “harvest” the disease in a transmissible form.

In the spring of 1864 an outbreak of yellow fever occurred in Bermuda. Blackburn offered his services to officials there who, aware of his reputation as an expert on the disease, quickly agreed. Blackburn ministered to the sick and, in the process, accumulated a large collection of clothing from the dead and dying. The idea was that the (supposedly) infectious clothing could be easily and widely distributed, spreading the disease silently and without a trace to its origin. Blackburn returned to Halifax in July 1864 with eight trunks packed with yellow fever victims’ clothing, along with a fine new valise packed with expensive new shirts. The trunks were to be delivered to New Bern, North Carolina, Norfolk, Virginia (both cities at the time being under Federal control) and Washington, D.C. The valise was special, Blackburn told his accomplice; he had previously stored fever victims’ clothing in it, and Hyams was to deliver it directly to the Executive Mansion in Washington, where he was to leave it as a personal gift for the president. Hyams flatly refused to deliver the valise, but took the rest to Washington, where he sold five trunks of clothing at a local auction house, and arranged to have the others sent on to Norfolk and New Bern. Hyams then returned to Toronto, where he found Blackburn preparing for another “collecting” trip to Bermuda.

This time Blackburn collected three trunks full of clothes stained and soiled with the infamous “black vomit” — actually half-digested blood from internal hemorrhaging — and other excretions of yellow fever victims, and made arrangements for them to be shipped to New York. By this time, though, it was fall and Blackburn decided to delay the shipment until the following spring, when rising temperatures would aid in the spread of the disease. Blackburn left his trunks full of clothing with a shipping agent named Swan, and boarded a steamer for Canada.

In the meantime, Hyams had gotten tired of cooling his heels in Canada, waiting for the $100,000 payoff that Blackburn kept promising but never came through on. He crossed the border to Detroit, strode into the U.S. attorney’s office there, and told all he knew in return for immunity. About the same time, local informants in Bermuda tipped off authorities about the trunks in storage there, and Blackburn’s game was up.

There is ample evidence to show that while Blackburn and Hyams were operating on their own initiative, they did so with the full cognizance of the Confederate government. Hyams revealed that funds for his Washington trip had been provided by Colonel Jacob Thompson, a Confederate operative who was involved in other covert operations to sow destruction and unrest in the North. Thompson’s secretary, a man named Cleary, was a close confidant of Jefferson Davis and revealed that the Confederate president was aware of the plot, although not directly involved in it. Davis and Blackburn had been friends before the war, and Davis had received two letters from a mutual acquaintance who told Davis of the plot, and urged him not employ such tactics against their enemy. Davis ignored the letters and did nothing to discourage Blackburn.

In April 1865 Blackburn was charged by the U.S. Bureau of Military Justice with conspiracy to commit murder, but he remained in Canada, outside the reach of military authorities. The Canadian government tried him for violating their neutrality laws, but he was acquitted and allowed to remain in Toronto. He returned to his native Kentucky, which had never been placed formally under congressional control during Reconstruction, in 1872 and gradually rebuilt his prewar medical practice. He successfully ran for governor of Kentucky, serving from 1879 to 1883.

Upon his death in 1887, Luke Pryor Blackburn was buried beneath a monument bearing a bronze relief depicting the Parable of the Good Samaritan.

h/t: Jane Johansson’s Trans-Mississippian Blog.

“We interrupt this blog. . .”

. . . for a totally non-Civil War-related post.

Via Conor Friedersdorf, the City of Philadelphia is demanding that small-time bloggers purchase a $300 business license, whether they actually make any money or not. Seemingly, the only criterion is that the blog be set up so that it might potentially generate income, through automated ads or similar, common tools.

I doubt this effort will go very far — after all, income from blogging is taxable under prevailing tax codes anyway, and most small bloggers (myself included) don’t think of their effort as a business in any case, but it’s still a troublesome development.

Update, August 24: Oh, my, looks like I’ve really set off Robert over at Cenantua. Poor man’s so upset, he’s speaking in tongues! 😉 And just to clarify, he’s dead right about this.

Update 2, August 24: Matt Yglesias picks up on this story at CAP. One of his commenters pushes back:

Similar to the danger of barbers cutting people’s throats, a blog in untrained hands is a dangerous thing.

What if an untrained blogger does not know the proper colors that should be used for a pleasant reading experience that doesn’t strain the eyes? Or if he/she uses too much white in the background, causing unnecessary electricity usage all over Philadelphia?

It only makes sense that Philadelphia would protect its constituents from these dangers.

Ha!

“One of them was a better soldier than I was.”

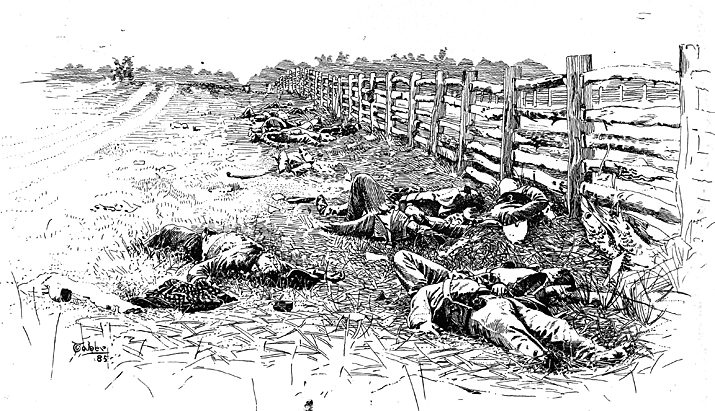

Private Lawrence Daffan, Co. G, Fourth Texas Infantry, at Sharpsburg (Antietam), September 17, 1862:

Then the Texas Brigade was ordered to charge; the enemy was on the opposite side of this stubblefield in the cornfield. As we passed where Lawton’s Brigade had stood, there was a complete line of dead Georgians as far as I could see. Just before we reached the cornfield General Hood rode up to Colonel [Benjamin F.] Carter, commanding the Fourth Texas Regiment (my regiment), and told him to front his regiment to the left and protect the flank. This he did and he made a charge directly to the west. We were stopped by a pike fenced on both sides. It would have been certain death to have climbed the fence.

Hays’ Louisiana Brigade had been in on our left, and had been driven out. Some of their men were with us at this fence. One of them was a better soldier than I was. I was lying on the ground shooting through the fence about the second rail; he stood up and shot right over the fence. He was shot through his left hand, and through the heart as he fell on me, dead. I pushed him off and saw that “Seventh Louisiana” was on his cap.

The Fifth [Texas], First [Texas] and Eighteenth Georgia, which was the balance of my brigade, went straight down into the cornfield, and when they struck this cornfield, the corn blades rose like a whirlwind, and the air was full.

Lawrence Daffan was seventeen years old at the time. He survived this fight, and the assault on Little Round Top at Gettysburg the following year, only to be captured in late 1863 and spend the remainder of the war as a prisoner at Rock Island, Illinois.

Quotation from Voices of the Civil War: Antietam (Time-Life, Inc., 1996). Image: “The Hagerstown Pike,” by Walton Taber.

Site of Ft. Lawton PoW Camp in Georgia Found

Via RCWEC Dummy Blog, archaeologists in Georgia have found the site of Camp Lawton, near the Georgia-South Carolina border:

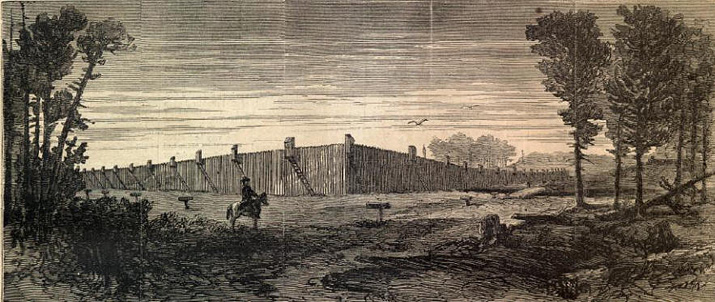

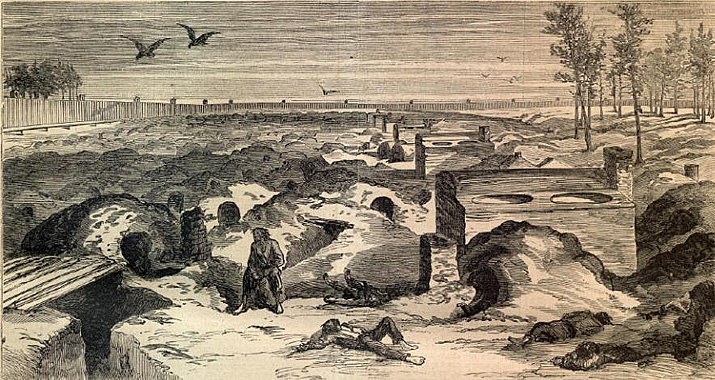

Outside of scholars and Civil War buffs, few people have heard of the Confederacy’s Camp Lawton, which replaced the infamous and overcrowded Andersonville prison in fall 1864.

For nearly 150 years, its exact location was not known, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and Georgia Southern University said.

Georgia Southern students earlier this year began their search at a state park and federal fish hatchery for evidence of the wall timbers and interior buildings. . . .

Life at Lawton, described as “foul and fetid,” wasn’t much better than at Andersonville, with the exception of plentiful water from Magnolia Springs.

In its six weeks’ existence, between 725 and 1,330 men died at the prison camp. The 42-acre stockade held about 10,000 men before it was hastily closed when Union forces approached.

There are no photos of Lawton and few visual stockade details, although a Union mapmaker painted some important watercolors of the prison. He also kept a 5,000-page journal that detailed the misery at Camp Lawton, which was built to hold up to 40,000 prisoners.

“The weather has been rainy and cold at nights,” Pvt. Robert Knox Sneden, who was previously imprisoned at Andersonville, wrote in his diary on Nov. 1, 1864. “Many prisoners have died from exposure, as not more than half of us have any shelter but a blanket propped upon sticks. . . . Our rations have grown smaller in bulk too, and we have the same hunger as of old.”

Images: Exterior and interior views of the Lawton PoW compound, from the January 7, 1865 issue of Harper’s Weekly. Via SonoftheSouth.com.

3 comments