On the Block

On Saturday, a group in St. Louis, Missouri re-enacted an antebellum slave auction on the steps of the city’s old courthouse. There are more photos here, and a news story about the planned event from KSDK Channel 5. From Channel 5:

Angela deSilva takes her history seriously — as an adjunct professor of American Studies and as a Civil War era re-enactor of American slave history, based on a knowledge that began with stories from her grandmother.

“I can remember being very, very young and listening to her talk about her grandmother who had been a slave,” says deSilva. “And I remember asking her what a slave was.”

A frequent slave re-enactor at the Daniel Boone Home, deSilva is bringing her history lesson to the steps of the Old Courthouse in downtown St. Louis Saturday, staging a mock slave auction with the help of dozens of historical re-enactors from across the region. DeSilva says it the 150th anniversary of the Civil War this year that prompted her to recreate such a dark scene in St. Louis history.

“You need to remember that there was another aspect to this. That a whole race of people was freed as a result there of,” she says of America’s deadliest war.

The National Parks Service oversees the Old Courthouse and as far as anyone there knows this will be the first event of its kind since the real thing back in the 1860’s. And organizers are aware it will be disturbing for some.

“It’s not that it’s glorifying it,” says deSilva defending the idea. “Not at all. I have relatives that could have been sold on those very steps.”

“When you talk about the Holocaust everyone says, ‘don’t forget us, never let them forget.’ But sometimes in slavery we want to bury it. I personally, I can’t do it. I cannot do it. I guess because the slaves in my past have names.”

This is a bold effort that pushes back — hard — against so much of what’s being done in the way of reenactments as part of the Civil War Sesquicentennial, such as the SCV-sponsored reenactment of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis next week. The “auction” held today in St. Louis is itself a deeply controversial event, even among African American groups, and that’s to be expected. It recalls a demeaning and ugly part of our shared history, and it’s something that a great many people would simply like to relegate to books and museum exhibits. St. Louis is a particularly important place to recognize this aspect of antebellum history, as it was one of the main centers of the domestic slave trade, with dealers buying and selling wholesale, in enormous quantities (left, advertisements in the Daily Missouri Republican, December 18, 1853).

This is a bold effort that pushes back — hard — against so much of what’s being done in the way of reenactments as part of the Civil War Sesquicentennial, such as the SCV-sponsored reenactment of the inauguration of Jefferson Davis next week. The “auction” held today in St. Louis is itself a deeply controversial event, even among African American groups, and that’s to be expected. It recalls a demeaning and ugly part of our shared history, and it’s something that a great many people would simply like to relegate to books and museum exhibits. St. Louis is a particularly important place to recognize this aspect of antebellum history, as it was one of the main centers of the domestic slave trade, with dealers buying and selling wholesale, in enormous quantities (left, advertisements in the Daily Missouri Republican, December 18, 1853).

I’m really undecided about reenactments in general as a means of teaching history and, more than a conventional battle reenactment, this event in particular is fraught with opportunity for misinterpretation and misunderstanding. I just don’t know how well it works. But if it keeps the conversation going about the underlying issues of the war, how we interpret the conflict, and the myriad of perspectives involved, then that’s all to the good.

Update: Kevin has a long and thoughtful post on this event here; Bob Pollock has photos and comments here. And Abbi Telander has more reflections on it here:

This is part of our shared heritage. Whether or not your descendants [sic.] were involved does not negate the fact that we all share this history as Americans. We share the agonies of the enslaved as well as the fight of the abolitionist and the responsibility of the owners. We have a responsibility to our past to understand it and a responsibility to our future to do better. Our nation, forged under the debate over the rights of man, went to war in an attempt to determine whether we could be one country with this shared past. Our nation has been fighting ever since over who was right and who was wrong, who deserves the glory and who deserves the blame, who deserves the benefits of citizenship, and who needs to be remembered in the annals of history.

I dare anyone who stood in the cold this morning and watched as the story of buying and selling other people unfolded to say that our sins need to be forgotten. I dare anyone present to forget this day. As my baby kicked inside me, innocent and pure, I promised her that I would someday tell her what she couldn’t see today, and that she would know why it was important that she know, and why I cried when those little girls stood up to be sold.

_____________________________

Thomas Tobe and the Limits of Confederate Pension Records

Note: This post has been updated since it originally went online, to reflect Tobe’s service at a Confederate military hospital. Major changes from the original are marked in blue.

_______________

Corey Meyer, who blogs at The Blood of My Kindred, has been taking a closer look at pension records of individuals who have been claimed to be African Americans who served as soldiers in the Confederate Army. I think this is the right approach, for two reasons. First, it’s a rational way to cut through the routine (and unproductive) back-and-forth shouting of, “no, you’re wrong!”, to get at the actual evidence in specific cases. Second, this sort of methodical, “micro” approach to the evidence is much more likely to identify and confirm the existence of actual, verifiable African Americans who may have served as soldiers. Establishing a half-dozen solid, ironclad examples of such men that can be fully documented in contemporary records will do a better service to Civil War historiography that a thousand unidentified, undated photos of old black men at Confederate veterans’ reunions — let alone the outright frauds that occasionally turn up. It’s hard to find the proverbial needle in the haystack when someone’s throwing fistfuls of straw at you.

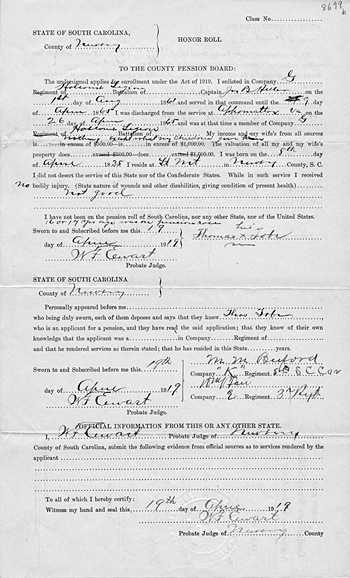

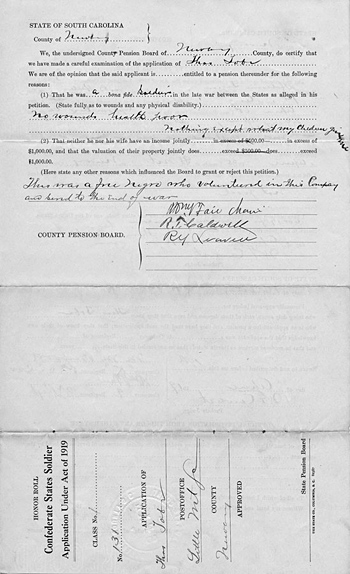

Recently, Corey took up the case of one Thomas Tobe (c. 1839 – 1922), a free African American man from Newberry County, South Carolina, who reportedly went to war with Company G of the 7th South Carolina Cavalry, Holcombe’s Legion. Tobe has been identified as a soldier based, it seems, entirely on the content of a 1919 South Carolina pension application where the local board ruled that Tobe had served as a soldier, and includes the notation that Tobe “was a free Negro who volunteered in this company and served to the end of war.” While the claim here is specific, the document (like all Confederate pension records) remains problematic, for reasons I’ll get to shortly.

Before getting into Thomas Tobe’s case in more detail, it’s important to look at Civil War pensions generally and remember how they were handled. This will be familiar ground to some readers, but it bears repeating, because it underscores why Confederate pension applications are not especially reliable sources for determining a man’s status in 1861-65.

Pensions for Union soldiers was handled by a central office within the federal government, where each claimant’s service was checked against official records compiled by the War Department. It was a centralized operation, with objective standards of service verification, with relatively little opportunity for personal influence i determining whether a man’s application was approved.

The situation was very different in the South, where pensions were set up by the individual states. Some states allowed pensions for black servants and other non-combatants, while others did not. Pensions were set authorized at different times, and so on. Generally speaking, each county or district was set up with its own pension board to evaluate and decide local cases. Because Confederate service records were somewhat fragmentary, and were not readily available to the local boards in any case, pensions were generally awarded based on the affidavit of witnesses to the man’s claimed service. Ideally these witnesses were other soldiers who had served in the same unit as the applicant, but often they were not. It was a system inherently weak on verification, capable of being manipulated for both good and ill purposes, with local political appointees issuing state pensions based on the affidavits of men who may or may not have actual first-hand knowledge of the applicants’ claims. Confederate pension records, absent corroborating documentation, cannot by themselves be considered definitive proof of the enlistment status of any individual veteran, white or black.

I should add that the basic primer to understanding the process for awarding Confederate pensions — and their limitations — remains James G. Hollandsworth, Jr.’s manuscript, “Looking for Bob: Black Confederate Pensioners After the Civil War,” in the Journal of Mississippi History.

Thomas Tobe’s name has been cited before as a “black Confederate” in several places, including in the comments section over at Kevin’s place. In every case I can find, the claim directs back to these same pension documents without reference to any other evidence or, for that matter, providing any other information about Tobe at all. Tobe applied for a pension in 1919, under that year’s South Carolina Confederate Pension Act of 1919. Earlier South Carolina pensions had been issued primarily to men disabled by the war, or widows of men who died in Confederate service. The 1919 program included all veterans and widows over the age of sixty who had married veterans before 1890. But it did not include African Americans who had served as cooks, servants or in other non-combatant support roles; those men did not become eligible for pensions until 1923. Note that when one runs the search of South Carolina pensions as Ms. DeWitt suggests, the applications are listed in chronological order; Tobe’s name and 1919 application appear at the head of the list, with the next-earliest that of Wash Stenhouse, dated 1923.

I have been unable to find any contemporary (i.e., generated in 1861-65) military records for Thomas Tobe in the usual places, including the NPS Soldiers & Sailors Database or in the service record files via Footnote. Edit: However, as commenter BorderRuffian notes below, he does appear employed as a nurse on the roster of General Hospital No. 1 at Columbia, South Carolina for July and August 1864, having been attached to the hospital on June 30 of that year. Under “remarks,” the he entry carries the notation of “conscript Negro.” (There are also single-entry mentions of a black man named “Tobe” employed as a laborer in June 1863 at Meridian, Mississippi, and someone with the surname “Tobbe,” raced unknown, on the rolls of Co. C, 17th Regiment of South Carolina Volunteers. It’s not clear whether either of these refer to the Thomas Tobe discussed here; Tobe was a common 19th century nickname for Thomas.)

The term “nurse” here may encompass a wide range of duties. Bell Irvin Wiley, in Southern Negroes, 1861-1865, discusses the role of African Americans in Confederate hospitals during the war:

Slaves and free Negroes were employed as hospital attendants, ambulance drivers, and stretcher bearers. Their duties in the hospitals were the cleaning of wards, cooking, serving, washing, and, sometimes, attending the patients. In some hospitals all this work was done by convalescent soldiers. As the need f men became more acute in the later part of the war, Negroes were used more extensively, that the white men, convalescents included, might be available for fighting.

Wiley goes on to note that in 1864, the year Tobe is carried on the roster of the military hospital at Columbia, black hospital workers (or their masters, in the case of slaves) were authorized $400 annually in compensation.

The hospital roster also contradicts the assertion on Tobe’s pension claim that he served continuously with Holcombe’s Legion from 1861 through the end of the war.

The other factor that must be taken into account, of course, is that most all of the tens of thousands of African American men, slave and free, who were involved in one capacity or another with the Confederate Army served in non-combatant roles, as personal servants, cooks, teamsters, laborers, and so on. This is true for vast majority of men now publicly identified as “black Confederates,” as well, for whom detailed documentation exists. Based on the General Hospital No. 1 roster, I believe this is likely true for Thomas Tobe as well. Indeed, he may have also gone along with the 7th South Carolina as a civilian worker, in any number of roles. Although corroboration is lacking, I can easily see that happening. If this were the case — and it’s a speculative scenario — it would neatly explain both his absence from the regiment’s military roster and his claim, 55 years later, to have served with that regiment.

There are documented cases where African American men used different pension forms at different times to describe their wartime roles. The famous Holt Collier, for example, applied for a servant’s pension in Mississippi in 1906, and again in 1916, before applying as a soldier in 1924 and 1928. That, combined with the wide discretion given to local political appointees in determining who would qualify for a pension, it should be considered at least a possibility that the board in his case did not exercise particular rigor in his case to verify the claim made in the old man’s application. So it’s possible that Tobe, perhaps with the encouragement of someone with influence on the local pension board, encouraged him to apply for a pension. Having served as a nurse, and perhaps with other units as a civilian laborer or conscript, it’s easy to see how he and the pension board might both view him as being entitled to the meagre support it provided, whether he was technically eligible or not.

So was Thomas Tobe an honest-to-goodness Confederate soldier? The vocabulary here is important. I believe very much in keeping definitions as narrow as possible; otherwise terms get tossed around loosely to the point at which they have no real meaning. There’s a real tendency to conflate terms in this area of research so that historically-important distinctions between military and civilian personnel are blurred and confused. To me, the definition of “soldier” that matters in this discussion is that used at the time: carried on the muster rolls, with military rank and recognized as such by his peers. And while in-the-ranks Confederate solders were sometimes detailed off from their units to work in hospitals, there’s no indication that that’s the case here. By those lights, then, and based on this evidence, I’d argue that the evidence does not fully confirm Thomas Tobe’s claim as a Confederate soldier, but clearly did serve as a nurse in a military hospital, most likely as a civilian but under military orders. Confederate service? Yes. As a soldier? I’m dubious, but open to further research findings.

As Kevin often points out, the lives of alleged “black Confederates” rarely get any attention at all apart from their supposed status as Confederate soldiers; those who cite them typically don’t dig much further beyond the one document that, to them, makes their chosen point. So while I retain some skepticism about whether Thomas Tobe was recognized as a soldier in the 7th South Carolina Cavalry during the war, I would like to share what else I have found out about him.

I was able to trace Thomas Tobe through most of the U.S. Censuses from 1850 to 1920. I could not find him in the 1860 Census, and the 1890 Census was destroyed in a fire, but he shows up in the others. The pension record gives his birth date as 1835, but various censuses indicate a birth date as late as 1839. His gravesite gives a birthdate of February 6, 1833, but I’m more inclined to trust the the early censuses, including the 1850 census, that reflect a birthdate of around 1839. It appears that, apart from the war years, he spent his entire life in central South Carolina, in Newberry and Lexington Counties, just west of Columbia.

In 1850 Tobe is lasted as being age 11, the son of William and Mary Tobe of Hellers (now Hellers Creek?), Newberry County, ages 50 and 35 respectively. William Tobe is listed as a farmer. Thomas has three siblings — Mary (15), Young W. (5) and Lucy (3). Thomas Tobe is described here as “Mulatto,” while in all following censuses he’s described as “Black.”

In 1870 Thomas Tobe is listed as a farm laborer in Newberry County, his age given as 31 He is married to Elizabeth, age 25, and they have four children residing with them — Delia (12), Thomas Jr. (9), William (7), John ( 4), and Samuel (1). Also living with them is a black farm laborer, George Wadsworth, age 23. Other records indicate Elizabeth’s maiden name was Wadsworth.

In 1880, Thomas is still in Hellers, now giving his age as 44. Elizabeth — giving her name as Betty — gave her age again as 25. Living with them are their children Thomas (17), William(15), John(14), Samuel (13), Garibaldi (12), Julius (10), Ebenezer (9), Hayes (8), and Florence (6). In that year’s agricultural census, Tobe is a renter on a 64-acre farm.

In 1900, Tobe is still in Hellers, giving his age as 60. He provides his birth date as July 1839. Elizabeth, given as Bettie, gives her age as 55, with a birth date of January 1845. They indicate they’ve been married 35 years. Living with them are two grandsons, their names listed as Lon (12) and Kite (10). He is still renting a farmstead.

In 1910, Thomas and Elizabeth Tobe are still in Hellers, giving their ages as 75 and 68, respectively. Living with them is a grandson, Thomas, age 21. The elder Tobe now owns his farmstead, with a mortgage. Elizabeth reports that she is the mother of 17 children, 10 of whom are still living. (It’s not clear how many of their children died young, and were not noted by the census, but at least one died as an adult during Thomas and Elizabeth’s lifetimes — Delia in 1915, of unknown causes — and their sons Julius (1898) and Hayes (1904) were critically injured in violent encounters; it’s not clear if either son survived.

In 1920, Thomas and Elizabeth Tobe are living in Broad River, Lexington County, with their ages given as 84 and 73 respectively. Although the two of them comprise a single household, the next household in the census is their son John, age 52, and his family, so it appears the elder Tobes either lived next door, or perhaps in an apartment adjacent to John.

Thomas Tobe died on August 1, 1922, and Elizabeth followed on March 29, 1923. Both are reportedly buried in the cemetery at Fairview Baptist Church, near Newberry.

Taken together, these decennial snapshots suggest a man whose life was stable but very linear. He and Elizabeth never learned to read or write, but were married for at least 55 years and raised a large family. He was, in his last years, able to purchase his own farm. It’s possible that, apart from his travels during the war, Thomas Tobe did not travel much beyond the region of central South Carolina where he grew up.

Thomas Tobe’s case is a fascinating one. It warrants further research, both to further illuminate Tobe’s specific circumstances and, more broadly, to illustrate the complexities of the role the African Americans played in the Confederate military effort. While there’s still no separate documentation to confirm Tobe’s service in the 7th South Carolina Cavalry, a little digging (in this case by commenter BorderRuffian) does reveal Tobe’s service as a nurse at a military hospital, and perhaps may even hint that he went with them into the field as a civilian laborer with the Seventh. It’s a complex story, one that doesn’t fit easily into simple interpretations of the conflict.

________________________

West Point, Annapolis Records Now Online

In honor of Veterans Day, Ancestry.com has put online Military Academy and Naval Academy cadet records and applications from 1805 to 1908. These files will be available free through Sunday, November 14, after which they will be available by subscription. Not sure if there will be an additional fee, or if access to these new materials will be included in existing Ancestry subscriptions.

Entirely apart from being a tool for one’s own genealogy, I’ve found Ancestry to be a great resource for researching individual people more generally, what with its easy access to census records, birth and death notices, slave schedules, and so on. These additional West Point and Annapolis materials are a wonderful addition to Ancestry’s expanding scope. Can’t wait to dig in properly.

Paroled at Vicksburg

Sunday marked the 147th anniversary of the end of the siege of Vicksburg. One of the Confederate soldiers taken prisoner that day was 26-year-old William C. Denman (1836-1906), a private in Company B, 30th Alabama Infantry. William Denman grew up with four younger siblings in Calhoun County, Alabama, where his widower father, Blake Denman, was a well-to-do farmer. The elder Denman was a slaveholder. William enlisted in the 30th Alabama on March 5, 1862. The regiment served in the western theater and, as part of S. D. Lee’s Brigade, saw action in several skirmishes. It suffered heavy casualties at Champion’s Hill (May 16, 1863), where it suffered 229 killed, wounded and missing — roughly half its numbers. Retreating in the face of Union General Grant’s army, Confederate forces including the 30th Alabama withdrew into Vicksburg, where they were quickly trapped between the Federal army to the east and the Federal Navy on the Mississippi. As part of S. D. Lee’s brigade, the 30th Alabama was assigned the defense of the Railroad Redoubt, one of the strong points in the Vicksburg defenses. The fort was overrun in a bloody assault on May 22, but eventually recaptured after Confederate troops regrouped and counterattacked.

After a hard siege lasting several weeks, the Confederate general commanding at Vicksburg, John C. Pembeton, surrendered his force to Grant on July 4. Private Denman, along with about 18,000 other Confederate soldiers, was paroled a few days later.Grant described this process in his memoir:

Pemberton and his army were kept in Vicksburg until the whole could be paroled. The paroles were in duplicate, by organization (one copy for each, Federals and Confederates), and signed by the commanding officers of the companies or regiments. Duplicates were also made for each soldier and signed by each individually, one to be retained by the soldier signing and one to be retained by us. Several hundred refused to sign their paroles, preferring to be sent to the North as prisoners to being sent back to fight again. Others again kept out of the way, hoping to escape either alternative. . . .

As soon as our troops took possession of the city guards were established along the whole line of parapet, from the river above to the river below. The prisoners were allowed to occupy their old camps behind the intrenchments. No restraint was put upon them, except by their own commanders. They were rationed about as our own men, and from our supplies. The men of the two armies fraternized as if they had been fighting for the same cause. When they passed out of the works they had so long and so gallantly defended, between lines of their late antagonists, not a cheer went up, not a remark was made that would give pain. Really, I believe there was a feeling of sadness just then in the breasts of most of the Union soldiers at seeing the dejection of their late antagonists.

The 30th Alabama, like several other surrendered units from Vicksburg, was reorganized a short while later, and it appears that Denman continued with this reconstituted regiment. (The reorganization of these units using men who had been paroled became a subject of dispute between Union and Confederate forces, which the following year caused the Union to suspend almost all parole for captured Confederate soldiers.) In January 1864, Denman transferred to a cavalry regiment, in which he remained to the end of the war.

After the war Denman married Sarah Crankfield (1847-1932), of South Carolina. They lived in Alabama and Louisiana before settling in Marion County, Florida in 1875. There they farmed and, in their later years, operated a boarding house. They had ten children together, but only two survived to adulthood. In 1900 Denman applied for a pension based on injuries received in the war, claiming he was “incapacitated for manual labor” as a result of eating pea bread, an ersatz bread made of ground stock peas and cornmeal, during the siege of Vicksburg. It resulted, Denman claimed, in chronic gastritis and bilious dyspepsia. He died in 1906.

“I’m a Son of Confederate Veterans as well as a son of slavery.”

Cary Clack, a columnist for San Antonio Life and a descendant of both a Confederate cavalry officer and a slave, attends an SCV meeting and finds it to be an odd, but not-entirely-unpleasant experience:

I’d written a column sarcastically dismissive of Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell and Texas Gov. Rick Perry. While proclaiming my pride in being a child of the South and Southwest, I took issue with McDonnell’s initial declaration of Confederate History Month — on behalf of the Sons of Confederate Veterans — which ignored slavery, and with Perry’s earlier suggestion of secession.

The Heritage of Honor page on the SCV website didn’t mention the word “slavery” either, but I saw that membership is open to “all male descendants of any veteran who served honorably in the Confederate armed services” and that I qualified.

I wrote, “I’m a Son of Confederate Veterans as well as a son of slavery” and expected an application.

I got one, as well as an invitation to attend the May meeting, from Russ Lane, the affable head of Alamo Camp #1325. I never doubted I’d go, just as I never doubted I would be treated kindly.

Including wives, there were about 30 people in the meeting that began with “the Pledge of Allegiance” to “the United States of America,” which heartened me to know I wasn’t in the presence of secessionists.

Mr. Clack’s take on the encounter is interesting, and doesn’t easily fit into preconceived notions. It’s complicated, that’s for sure, and I hope he continues to write on this particular journey of his. It’s challenging enough thinking about one’s Confederate ancestors, who marched and fought and sometimes died in the uniform of a nation established to preserve and expand the institution of slavery; I can’t even imagine how to begin approaching the knowledge that one of your ancestors considered another to be his personal property.

8 comments