Site of Ft. Lawton PoW Camp in Georgia Found

Via RCWEC Dummy Blog, archaeologists in Georgia have found the site of Camp Lawton, near the Georgia-South Carolina border:

Outside of scholars and Civil War buffs, few people have heard of the Confederacy’s Camp Lawton, which replaced the infamous and overcrowded Andersonville prison in fall 1864.

For nearly 150 years, its exact location was not known, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and Georgia Southern University said.

Georgia Southern students earlier this year began their search at a state park and federal fish hatchery for evidence of the wall timbers and interior buildings. . . .

Life at Lawton, described as “foul and fetid,” wasn’t much better than at Andersonville, with the exception of plentiful water from Magnolia Springs.

In its six weeks’ existence, between 725 and 1,330 men died at the prison camp. The 42-acre stockade held about 10,000 men before it was hastily closed when Union forces approached.

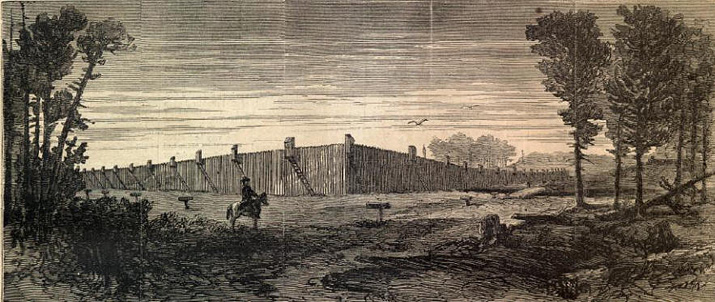

There are no photos of Lawton and few visual stockade details, although a Union mapmaker painted some important watercolors of the prison. He also kept a 5,000-page journal that detailed the misery at Camp Lawton, which was built to hold up to 40,000 prisoners.

“The weather has been rainy and cold at nights,” Pvt. Robert Knox Sneden, who was previously imprisoned at Andersonville, wrote in his diary on Nov. 1, 1864. “Many prisoners have died from exposure, as not more than half of us have any shelter but a blanket propped upon sticks. . . . Our rations have grown smaller in bulk too, and we have the same hunger as of old.”

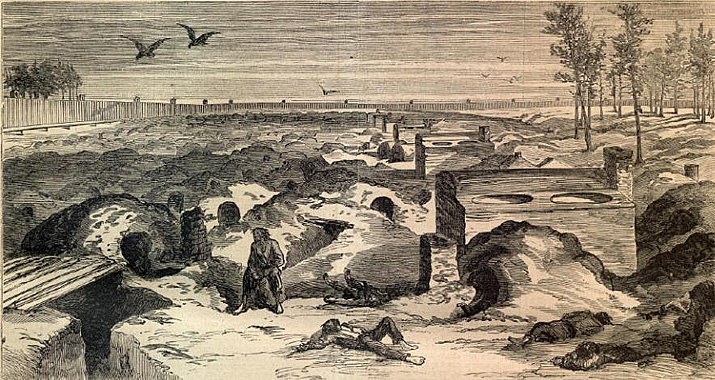

Images: Exterior and interior views of the Lawton PoW compound, from the January 7, 1865 issue of Harper’s Weekly. Via SonoftheSouth.com.

Suitably awful illustration. But was there ever a POW camp that passed the muster of the morally-comfortable civilian years after the fact? Pity Harper’s never did any drawings of Point Lookout or the dark lockup in Baltimore where Simon Baruch and his fellow surgeons were held after Gettysburg. “War is all hell,” as Sherman said, and did his best to make it that way.

Let’s not get into a pissing match about whether this or that prison camp was worse, all right? That really leads nowhere.

I was glad to find a contemporary illustration of the interior of the compound other than Sneden’s, which has been posted all over the place during the last week. If you can suggest another to use instead, let me know.

My husband’s grandfather survived Point Lookout, MD – we don’t know how – but he did. We think he lost

an eye there from disease. We don’t have a picture showing that – but he was captured in the last battle of the Civil War in NC – his name is on the plaque at the State Park. I purchased a book about Point Lookout – a lot of the men survived using vinegar – sort of an antiseptic – imagine that! Thank you for writing your post. His grandfather’s name was Franklin James Anders, a farmer of NC.

Point Lookout was a horrid place, though fortunately Anders wasn’t there very long, having been captured at Bentonville on March 19, 1865, and paroled from Point Lookout on June 4. He was on the sick list at that time, and was immediately transferred to the General Hospital at Fort Monroe, listed as “conval[escent] from typhoid fever.”

Vinegar is acidic, so it’s actually pretty good as a cleaner and not too bad as an antiseptic.

From his CSR, it looks like Anders spent a good bit of his wartime service detached to the Signal Corps around Wilmington and Cape Fear, some of it like in and around Fort Fisher. Lots of blockade-running and other naval activity going on there, and consequently lots of signalling.

Thanks for stopping by.

I have nothing against the illustration, and no idea of whether it’s representative or not. If men were left in the open with no shelter, it makes sense they would burrow. I suppose Harper’s could have snuck an artist down there in early ’65, or merely taken an escapee’s testimony.

Nor am I trying to start a pissing match. I expect CNN will be doing that with such stories for the next four years. I don’t expect they’ll be interested in balance, balance already seeming to elude them on so much else.

You raise a fair question regarding the accuracy of the image. Correspondents and artists from the big papers did travel with the armies, sending back dispatches and sketches for the engravers to turn into press-ready illustrations. Digging a bit into that same issue of Harper’s Weekly, that seems to have been the case here:

Sneden’s illustration of the compound seems to show some burrowing, too, along with lots of makeshift shelters made of scrounged wood, scraps of canvas, etc.

Additional: There’s a good bit of correspondence related to the organization and construction of the camp at Millen/Fort Lawton in the AOR vols. 120 and 121, including a plan (v. 120, p. 882) of the proposed compound. (Not sure if this was actually followed.) There is also some material compiled during postwar investigations, including one (v. 121, p. 765) that “the prisoners had an abundant supply of wood, water, and provisions, but no shelter, in consequence of which the fatality was very great.”

Thanks, that makes sense. I’m sure the Confeds could have built shelters if they cared to, but since the North already was refusing to repatriate Southern prisoners, tearing up the landscape and blockading the coasts, I can see why they wouldn’t care much.

Re the idea of balance in such stories, I should add that it won’t entirely be CNN’s or any other outlet’s fault if they don’t balance them. The material they will be digging out and using was mainly one-sided to begin with.

Sort of like the monuments at Gettysburg which were almost all Union for almost a hundred years after the war—the Southern states being too poor to put them up and hardly interested in commemorating a loss in any case. And journalists being a lazy bunch (I’m a retired one), they’re not likely to do the original research it would take to provide any sort of balance to the old slanders and libels.

I could be wrong, but I suspect we’re all going to be surprised at the level of anomosity that’s going to surface with the resurrection of this stuff during the Sesqui.

You’re probably right about the animosity; it never really went away. The warm-and-fuzzy, hands-across-the-wall theme of reconciliation (see the picture from my previous post) has always been largely false, IMO, but perhaps necessary, a sort of mutually-agreed-upon collective amnesia that let us move forward as a nation. Sort of like a couple that has some enormous, ugly scar in their relationship, that they “deal with” by refusing to openly discuss and come to terms with it. It allows them to function, though in a dysfunctional way.

Reminds me of a discovery I made years ago at the NPS office at Appomattox CH. They were selling postcards of a late 19th Cen. painting showing Grant and Lee sitting at the same table to conclude the surrender documents.

But they were also selling a poster of a print, which they said was the accurate version, showing Grant and Lee at separate tables with their aides passing the documents back and forth. No postcards of it on sale, however. Maybe they’ve changed that by now.

Andy, thanks for posting this. My great-great grandfather was sent here between stints at Andersonville and Savannah. He wrote that he made it out of Andersonville by answering to the name of a prisoner who had died the night before when they were calling out names of prisoners who were to be transferred.

Thanks. I’d be glad to hear more about your g-g-grandfather.

My husband’s cousin from PA fought in the Civil War for a PA unit. He is buried at Andersonville, GA prison sight. They have a fine computer look-up there – we found his commemorative marker easily and took pictures of it. We don’t know where he is actually buried. He was a descendant of Nicholas Coleman who was born in Scotland in 1731 and immigrated to PA. There he went west into Indiana County – but had to scurry out

and find a fort quickly when Indians burned his cabin. The family never found the items they had buried.

Descendants still live in the Conemaugh Community around there in Indiana County. I am sure Nicholas never dreamed a fine young male descendant would fight and die in a Civil War, and that his body would never

be returned to his home place. Andersonville had a tragic history and the Commandant was tried and convicted later. Some of Nicholas Coleman’s descendants also fought in the War of 1812 and my husband

was a Veteran of the Korean War. Seems down the lineage that many had to defend what they thought

was the United States and a place of freedom. The Colemans left Scotland because of English oppression.

My understanding is that the vast, vast majority of burials at Andersonville are identified, so the stone you saw may be his actual grave marker. Obviously they didn’t have modern forensic techniques to confirm the identities of the remains uncovered, but they were working from a nearly-complete index to the burials. This story is detailed in Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering. The national cemetery there has the lowest proportion of “unknown” graves of any from that conflict.

Forgot to use my real name. 😉

My great-great grandfather, Benjamin Cruiser McWilliams enlisted in the 16th PA Cavalry in late July, 1863, was captured in October 1863, and made a tour of five Confederate prisons: Libby, Belle Island, Andersonville, Savannah and Millen. I have to check my written notes for the exact order of the last two; we are doing some home renovations and stuff is boxed up right now. He spent the most time in Belle Island (late Oct-late Feb) and Andersonville (March 1, 1864 until around Sep-Oct 1864 – dates are approximate).

He wrote a couple of versions of his experiences (probably about 30-40 years after the war) that my uncle typed up and someone later put into a binder; also, I have copies of his pension records.

Thanks for sharing that info.

What a great treasure you have – “versions of his experiences” I hope you will give copies to a Museum

that would appreciate them – and I hope family will also appreciate that they even exist.

“David,”

I am a historian who has studied the Camp Lawton story for three decades. I was the proejct historian for the 2010 dig that “resurrected” the prison. I collect first-person accounts of POWs who were at Camp Lawton, and I would very much like to see the typescript you mentioned. Camp Lawton is not as well documented as Libby, Anderrsonville, etc., and every little scrap of POW recollection is important to us. I would love to be able to add your ancestors story to our files. Contact me at jderden@ega.edu.

I am the project historian for the Camp Lawton dig. Iwould be very interested in getting a copy of the transcript of your ancestor’s POW story. Very few POW recollections of Camp Lawton exist, and every scrap of information about the prison helps us to interpret its history. “David,” contact me if you would be willing toshare that information with us: jdedfen@ega.edu.

John, I just saw your comment and sent an e-mail.