“This was the grandest thing I saw during the war.”

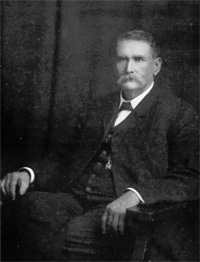

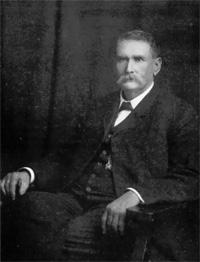

Today is the sesquicentennial of the Second Battle of Manassas. Yesterday we had an account of that action recorded by Val Giles, of Company B of the 4th Texas Infantry, describing the action against a Union Zouave regiment and the actions of the James Reilly’s battery, attached to the Texas Brigade. Today, we have a parallel account of the same action, by Lawrence Daffan (right), then a seventeen-year-old private in Company G of the 4th Texas. Years later, Daffan dictated his account to his daughter Katie, who was herself secretary of the Brigade Association, active in UDC affairs and, the following year, would be named superintendent of the Texas Confederate Woman’s Home. The story was subsequently published in a commemorative book, Unveiling and Dedication of Monument to Hood’s Texas Brigade on the Capitol Grounds at Austin, Texas. It contains a wealth of information about the famous brigade, collected from wartime records and surviving veterans.

Today is the sesquicentennial of the Second Battle of Manassas. Yesterday we had an account of that action recorded by Val Giles, of Company B of the 4th Texas Infantry, describing the action against a Union Zouave regiment and the actions of the James Reilly’s battery, attached to the Texas Brigade. Today, we have a parallel account of the same action, by Lawrence Daffan (right), then a seventeen-year-old private in Company G of the 4th Texas. Years later, Daffan dictated his account to his daughter Katie, who was herself secretary of the Brigade Association, active in UDC affairs and, the following year, would be named superintendent of the Texas Confederate Woman’s Home. The story was subsequently published in a commemorative book, Unveiling and Dedication of Monument to Hood’s Texas Brigade on the Capitol Grounds at Austin, Texas. It contains a wealth of information about the famous brigade, collected from wartime records and surviving veterans.

On that August afternoon in 1862, Daffan and his comrades witnessed what later came to be known as “the very vortex of Hell.” At the center of that conflagration stood the famous Fifth New York Volunteers, Duryée’s Zouaves. They took the full brunt of the attack by Daffan’s counterparts in the Fifth Texas, and Hampton’s Legion of South Carolinians, and the Eighteenth Georgia. The Zouaves held on as long as they could, and were effectively wiped out as a fighting unit. Of 525 “redlegs” who marched into the fight that day, 332 were killed or wounded, a casualty rate of 63%.

Note: the original work as published, linked in the first paragraph above, has numerous small errors in dates, spelling of names, and so on. It’s impossible at this point to know if these were errors made by Lawrence Daffan, Katie Daffan, or the typesetter. I’ve corrected (or tried to) all those in the text below, without noting individual instances. Those wishing to see the uncorrected text can click the first link above to read the original, beginning on p. 187 of the original book, or n218 in the electronic version.

On Thursday evening, August 28, 1862, marching through the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, we heard the sound and echo of artillery, which was familiar to us, and we knew that we were approaching the enemy.

Just before sundown we entered Thoroughfare Gap. We could hear musketry and artillery at the opposite side of the gap. Anderson’s Brigade had engaged the enemy, who was holding the gap, to keep us from forming a junction with Jackson at Manassas.

Hood’s Brigade filed out of the road and started right over the top of the mountain, which was very steep climbing. By the time we were at the top we received word that Anderson had routed the enemy. We returned to the road and continued that night and marched through the gap and camped right on the ground where Anderson had driven them away. We were ordered to be ready to move at a moment’s warning. We started at 6 o’clock Friday morning, August 29.

I speak of Hood’s division in this, which consisted of Benning’s Brigade and Anderson’s Georgia Brigade, Law’s Alabama Brigade and Hood’s Texas Brigade. Hood was, at this time, Brigadier General, but acting in the capacity of Major General for this division.

We marched along in ordinary time to Manassas, until 9 or 10 o’clock. At this time we began to hear very heavy cannonade. In an hour we were in the hearing of very heavy artillery and musketry, fierce and violent. Jackson had engaged Pope and his corps. The sound of the firing continued to grow more violent. We received orders to quickstep and shortly afterward received orders to double quickstep. We were all young and stout, and it seemed to me this kept up about two hours. Pope was pressing Jackson very hard at this point. We joined Jackson and formed at his right and double-quicked into line of battle and threw out skirmishers.

At this time, as we arrived there, the firing all along Jackson’s line ceased at once. We took position Friday evening, and Friday night we had a night attack. This and the attack at Raccoon Mountain, Tennessee, were the only night attacks that I know of made by the Confederates. This attack caused great confusion, and I could never understand what benefit it was. We slept that night very close to the enemy, in fact could not speak aloud or above a whisper. I had a very bad cold at this time, contracted on the retreat from Yorktown, and an officer was sent from headquarters “to tell than man who was constantly coughing to go from the front to the rear, where he could not be heard.” I went back, near half a mile, with my blanket and accouterments. I slept alone, under a large oak tree, coughing all night. I didn’t know the maneuvers of our regiment between this [time] and day[light], but I joined them early Saturday morning [August 30]. We formed in perfect order early in the day. Jackson brought on the attack on our left about noon and pressed the enemy until they began to give way in front of him. This drew a number of troops from in front of us to support those Jackson, was driving back on our left.

General Lee’s headquarters were in sight of where I was. About 4 o’clock in the afternoon I saw a considerable commotion in General Lee’s headquarters; he, his staff officers and couriers. The couriers darted off with their instructions to different commanders of divisions, in a few minutes a courier dashed up to General [Jerome B.] Robertson, commanding the Texas Brigade. These couriers and orderlies notified the respective Colonels. The order “attention” was given, then the order “to load,” then “forward,” “guide center.” We went through the heavy timber and emerged into an open field. We had a famous battery with us, [Captain James] Reilly’s Battery [Rowan Artillery], with six guns, four Napoleon and two six-p0und rifles.

Captain Reilly had always promised us that if the location of the company permitted, he would charge with us. We opened and made room between the Fourth and Fifth Texas for Reilly’s Battery to come in. As we started, the battery started.

Young’s Branch was between us and a hill on the other side, which was occupied by a Federal Battery [Curran’s Battery], which was playing on us. This turned into a charge as soon as we emerged from the timber. We had gone a short distance when Reilly unlimbered two of his guns and opened on the Federals. We moved past these guns while they were firing. As we passed on the other two guns came in some distance ahead of those that were firing, swung into position and unlimbered. It seemed to me by the time the first two had stopped, the second two opened fire. This was done remarkably quick. They charged with us in this charge until we arrived at Young’s Branch ; two sections, two Napoleon guns each, two firing while the other two would limber up and run past them, swing into position and open fire.

This was the grandest thing I saw during the war — the charge of Reilly’s Battery with the Texas Brigade. I don’t know whether they shot accurately or not, it was done so fast. But I do know that it attracted the attention of the Yankee battery on the hill, diverting their attention from us.

Reilly’s Battery were North Carolinians and were with us all during the war and they never lost a gun.

In this charge at Manassas we saw a Zouave regiment [5th New York Volunteers, Duryée’s Zouaves]. It stood immediately in front of the Fifth Texas to our right. It was a very fine regiment. As the Fifth Texas approached, it checked the speed of the Fifth in its quick charge. The Fifth Texas, Hampton Legion and the Fourth Texas had a tendency to swing around them. As the Fifth Texas approached them, I saw the blaze of their rifles reached nearly from one to the other.

The First Texas, Hampton’s Legion and Fourth Texas from their position gave the Zouaves an enfilading fire, which virtually wiped them off the face of the earth. I never could understand why this fine Zouave regiment would make the stand they did in front of the brigade until nearly every one was killed.

We rallied at Young’s Branch. I looked up the hill which we had descended and the hill was red with uniforms of the Zouaves. They were from New York.

We ascended the hill out of Young’s branch, charged a battery of six guns [Curran’s], supported by a line of Pennsylvania infantry. This battery was near enough to use on us grapeshot and canister. As we came near to it one of the guns was pointed directly at my company and lanyard strung. Our Captain commanded Company G to right and left oblique from it. I was on the right and with a few others went into Company H. At this time one of the artillerymen threw the main beam, and this threw the cannon directly on Company H. Company H received a load of canister which killed four or five men.

I was immediately with Lieutenant [C. E.] Jones and [Private R. W.] Ransom of that company, who were both killed right at my feet. I stepped over both of them. Captain [James T.] Hunter, now living, was also shot down at that time. Most of the company were my schoolmates.

This last shot threw smoke and dust all over me, and the shot whizzed on both sides of me. Lieutenant Jones was shot in the head and feet, but I was not touched, When the smoke cleared away we had these guns, and they were so hot I couldn’t bear my hands on them. I then fired one shot at this retreating infantry which the rest of the brigade had been engaged with. This wound up that day’s engagement for us, except the Fifth Texas. A part of their regiment and their colors were carried about five miles after the retreating enemy.

We returned to Young’s branch and my attention was attracted to our support coming down the same hill that we had come down.

There were four lines of battle of Longstreet’s Corps in perfect order, which passed us and took up the fight with the retreating enemy where we left it off. This battle was fought on the 30th and 31st of August, 1862.

I can’t understand why the Federals have always attached so little importance to this battle, as they lost many gallant men there. They were terribly defeated, and may have been ashamed of their commanding general.

Image: 5th New York Zouaves, by Don Troiani

“This was the grandest thing I saw during the war.”

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the dedication of the Hood’s Texas Brigade Monument on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol in Austin. The following year the Brigade Association published a commemorative book, Unveiling and Dedication of Monument to Hood’s Texas Brigade on the Capitol Grounds at Austin, Texas. It contains a wealth of information about the famous brigade, collected from wartime records and surviving veterans.

One of the remarkable accounts in the book is this description of the brigade’s advance during the Second Battle of Manassas, late on the afternoon of August 30, 1862. The author is Lawrence Daffan (left), then a seventeen-year-old private from Montgomery County, Texas, assigned to Company G of the Fourth Texas Infantry. Years later, Daffan dictated his account to his daughter Katie, who was herself secretary of the Brigade Association, active in UDC affairs and, the following year, would be named superintendent of the Texas Confederate Woman’s Home.

One of the remarkable accounts in the book is this description of the brigade’s advance during the Second Battle of Manassas, late on the afternoon of August 30, 1862. The author is Lawrence Daffan (left), then a seventeen-year-old private from Montgomery County, Texas, assigned to Company G of the Fourth Texas Infantry. Years later, Daffan dictated his account to his daughter Katie, who was herself secretary of the Brigade Association, active in UDC affairs and, the following year, would be named superintendent of the Texas Confederate Woman’s Home.

On that August afternoon, Daffan and his comrades witnessed what later came to be known as “the very vortex of Hell.” At the center of that conflagration stood the famous Fifth New York Volunteers, Duryée’s Zouaves. They took the full brunt of the attack by Daffan’s counterparts in the Fifth Texas, and Hampton’s Legion of South Carolinians, and the Eighteenth Georgia. The Zouaves held on as long as they could, and were effectively wiped out as a fighting unit. Of 525 “redlegs” who marched into the fight that day, 332 were killed or wounded, a casualty rate of 63%.

Note: the original work as published, linked in the first paragraph above, has numerous small errors in dates, spelling of names, and so on. It’s impossible at this point to know if these were errors made by Lawrence Daffan, Katie Daffan, or the typesetter. I’ve corrected (or tried to) all those in the text below, without noting individual instances. Those wishing to see the uncorrected text can click the first link above to read the original, beginning on p. 187 of the original book, or n218 in the electronic version.

On Thursday evening, August 28, 1862, marching through the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, we heard the sound and echo of artillery, which was familiar to us, and we knew that we were approaching the enemy.

Just before sundown we entered Thoroughfare Gap. We could hear musketry and artillery at the opposite side of the gap. Anderson’s Brigade had engaged the enemy, who was holding the gap, to keep us from forming a junction with Jackson at Manassas.

Hood’s Brigade filed out of the road and started right over the top of the mountain, which was very steep climbing. By the time we were at the top we received word that Anderson had routed the enemy. We returned to the road and continued that night and marched through the gap and camped right on the ground where Anderson had driven them away. We were ordered to be ready to move at a moment’s warning. We started at 6 o’clock Friday morning, August 29.

I speak of Hood’s division in this, which consisted of Benning’s Brigade and Anderson’s Georgia Brigade, Law’s Alabama Brigade and Hood’s Texas Brigade. Hood was, at this time, Brigadier General, but acting in the capacity of Major General for this division.

We marched along in ordinary time to Manassas, until 9 or 10 o’clock. At this time we began to hear very heavy cannonade. In an hour we were in the hearing of very heavy artillery and musketry, fierce and violent. Jackson had engaged Pope and his corps. The sound of the firing continued to grow more violent. We received orders to quickstep and shortly afterward received orders to double quickstep. We were all young and stout, and it seemed to me this kept up about two hours. Pope was pressing Jackson very hard at this point. We joined Jackson and formed at his right and double-quicked into line of battle and threw out skirmishers.

At this time, as we arrived there, the firing all along Jackson’s line ceased at once. We took position Friday evening, and Friday night we had a night attack. This and the attack at Raccoon Mountain, Tennessee, were the only night attacks that I know of made by the Confederates. This attack caused great confusion, and I could never understand what benefit it was. We slept that night very close to the enemy, in fact could not speak aloud or above a whisper. I had a very bad cold at this time, contracted on the retreat from Yorktown, and an officer was sent from headquarters “to tell than man who was constantly coughing to go from the front to the rear, where he could not be heard.” I went back, near half a mile, with my blanket and accouterments. I slept alone, under a large oak tree, coughing all night. I didn’t know the maneuvers of our regiment between this [time] and day[light], but I joined them early Saturday morning [August 30]. We formed in perfect order early in the day. Jackson brought on the attack on our left about noon and pressed the enemy until they began to give way in front of him. This drew a number of troops from in front of us to support those Jackson, was driving back on our left.

General Lee’s headquarters were in sight of where I was. About 4 o’clock in the afternoon I saw a considerable commotion in General Lee’s headquarters; he, his staff officers and couriers. The couriers darted off with their instructions to different commanders of divisions, in a few minutes a courier dashed up to General [Jerome B.] Robertson, commanding the Texas Brigade. These couriers and orderlies notified the respective Colonels. The order “attention” was given, then the order “to load,” then “forward,” “guide center.” We went through the heavy timber and emerged into an open field. We had a famous battery with us, [Captain James] Reilly’s Battery [Rowan Artillery], with six guns, four Napoleon and two six-p0und rifles.

Captain Reilly had always promised us that if the location of the company permitted, he would charge with us. We opened and made room between the Fourth and Fifth Texas for Reilly’s Battery to come in. As we started, the battery started.

Young’s Branch was between us and a hill on the other side, which was occupied by a Federal Battery [Curran’s Battery], which was playing on us. This turned into a charge as soon as we emerged from the timber. We had gone a short distance when Reilly unlimbered two of his guns and opened on the Federals. We moved past these guns while they were firing. As we passed on the other two guns came in some distance ahead of those that were firing, swung into position and unlimbered. It seemed to me by the time the first two had stopped, the second two opened fire. This was done remarkably quick. They charged with us in this charge until we arrived at Young’s Branch ; two sections, two Napoleon guns each, two firing while the other two would limber up and run past them, swing into position and open fire.

This was the grandest thing I saw during the war — the charge of Reilly’s Battery with the Texas Brigade. I don’t know whether they shot accurately or not, it was done so fast. But I do know that it attracted the attention of the Yankee battery on the hill, diverting their attention from us.

Reilly’s Battery were North Carolinians and were with us all during the war and they never lost a gun.

In this charge at Manassas we saw a Zouave regiment [5th New York Volunteers, Duryée’s Zouaves]. It stood immediately in front of the Fifth Texas to our right. It was a very fine regiment. As the Fifth Texas approached, it checked the speed of the Fifth in its quick charge. The Fifth Texas, Hampton Legion and the Fourth Texas had a tendency to swing around them. As the Fifth Texas approached them, I saw the blaze of their rifles reached nearly from one to the other.

The First Texas, Hampton’s Legion and Fourth Texas from their position gave the Zouaves an enfilading fire, which virtually wiped them off the face of the earth. I never could understand why this fine Zouave regiment would make the stand they did in front of the brigade until nearly every one was killed.

We rallied at Young’s Branch. I looked up the hill which we had descended and the hill was red with uniforms of the Zouaves. They were from New York.

We ascended the hill out of Young’s branch, charged a battery of six guns [Curran’s], supported by a line of Pennsylvania infantry. This battery was near enough to use on us grapeshot and canister. As we came near to it one of the guns was pointed directly at my company and lanyard strung. Our Captain commanded Company G to right and left oblique from it. I was on the right and with a few others went into Company H. At this time one of the artillerymen threw the main beam, and this threw the cannon directly on Company H. Company H received a load of canister which killed four or five men.

I was immediately with Lieutenant [C. E.] Jones and [Private R. W.] Ransom of that company, who were both killed right at my feet. I stepped over both of them. Captain [James T.] Hunter, now living, was also shot down at that time. Most of the company were my schoolmates.

This last shot threw smoke and dust all over me, and the shot whizzed on both sides of me. Lieutenant Jones was shot in the head and feet, but I was not touched, When the smoke cleared away we had these guns, and they were so hot I couldn’t bear my hands on them. I then fired one shot at this retreating infantry which the rest of the brigade had been engaged with. This wound up that day’s engagement for us, except the Fifth Texas. A part of their regiment and their colors were carried about five miles after the retreating enemy.

We returned to Young’s branch and my attention was attracted to our support coming down the same hill that we had come down.

There were four lines of battle of Longstreet’s Corps in perfect order, which passed us and took up the fight with the retreating enemy where we left it off. This battle was fought on the 30th and 31st of August, 1863.

I can’t understand why the Federals have always attached so little importance to this battle, as they lost many gallant men there. They were terribly defeated, and may have been ashamed of their commanding general.

Image: 5th New York Zouaves, by Don Troiani

2 comments