“Ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave.”

It would be a shame to let April slip by without a mention of Texas State Senate Resolution No. 526, which designates this month as Texas Confederate History and Heritage Month. The resolution uses a lot of boilerplate language (including an obligatory mention of “politically correct revisionists”), and also makes the assertion that “ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers never owned a slave.” This is a common argument among Confederate apologists, part of a larger effort to minimize or eliminate the institution of slavery as a factor in secession and the coming of the war, and thus make it possible to maintain the notion that Southern soldiers, like the Confederacy itself, were driven by the purest and noblest values to defend home and hearth. Slavery played no role it the coming of the war, they say; how could it, when less than two percent (four percent, five percent) actually owned slaves? In fact, they’d say, their ancestors had nothing at all to do with slavery.

But it’s wrong.

It’s true that in an extremely narrow sense, only a very small proportion of Confederate soldiers owned slaves in their own right. That, of course, is to be expected; soldiering is a young man’s game, and most young men, then and now, have little in the way of personal wealth. As a crude analogy, how many PFCs and corporals in Iraq and Afghanistan today own their own homes? Not many.

But even if it is narrowly true, it’s a deeply misleading statistic, cited religiously to distract from the much more relevant number, the proportion of soldiers who came from slaveholding households. The majority of the young men who marched off to war in the spring of 1861 were fully vested in the “peculiar institution.” Joseph T. Glatthaar, in his magnificent study of the force that eventually became the Army of Northern Virginia, lays out the evidence.

Even more revealing was their attachment to slavery. Among the enlistees in 1861, slightly more than one in ten owned slaves personally. This compared favorably to the Confederacy as a whole, in which one in every twenty white persons owned slaves. Yet more than one in every four volunteers that first year lived with parents who were slaveholders. Combining those soldiers who owned slaves with those soldiers who lived with slaveholding family members, the proportion rose to 36 percent. That contrasted starkly with the 24.9 percent, or one in every four households, that owned slaves in the South, based on the 1860 census. Thus, volunteers in 1861 were 42 percent more likely to own slaves themselves or to live with family members who owned slaves than the general population.

The attachment to slavery, though, was even more powerful. One in every ten volunteers in 1861 did not own slaves themselves but lived in households headed by non family members who did. This figure, combined with the 36 percent who owned or whose family members owned slaves, indicated that almost one of every two 1861 recruits lived with slaveholders. Nor did the direct exposure stop there. Untold numbers of enlistees rented land from, sold crops to, or worked for slaveholders. In the final tabulation, the vast majority of the volunteers of 1861 had a direct connection to slavery. For slaveholder and nonslaveholder alike, slavery lay at the heart of the Confederate nation. The fact that their paper notes frequently depicted scenes of slaves demonstrated the institution’s central role and symbolic value to the Confederacy.

More than half the officers in 1861 owned slaves, and none of them lived with family members who were slaveholders. Their substantial median combined wealth ($5,600) and average combined wealth ($8,979) mirrored that high proportion of slave ownership. By comparison, only one in twelve enlisted men owned slaves, but when those who lived with family slave owners were included, the ratio exceeded one in three. That was 40 percent above the tally for all households in the Old South. With the inclusion of those who resided in nonfamily slaveholding households, the direct exposure to bondage among enlisted personnel was four of every nine. Enlisted men owned less wealth, with combined levels of $1,125 for the median and $7,079 for the average, but those numbers indicated a fairly comfortable standard of living. Proportionately, far more officers were likely to be professionals in civil life, and their age difference, about four years older than enlisted men, reflected their greater accumulated wealth.

The prevalence of slaveholding was so pervasive among Southerners who heeded the call to arms in 1861 that it became something of a joke; Glatthaar tells of an Irish-born private in a Georgia regiment who quipped to his messmates that “he bought a negro, he says, to have something to fight for.”

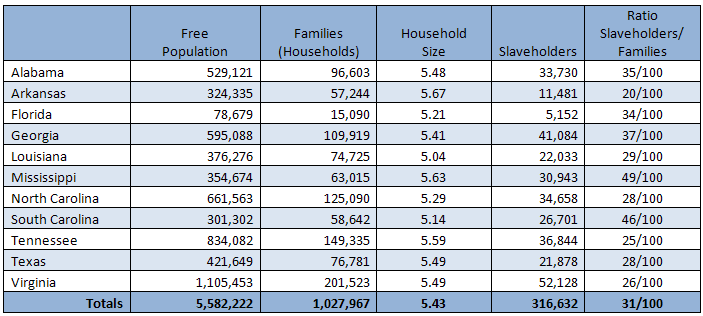

While Joe Glatthaar undoubtedly had a small regiment of graduate assistants to help with cross-indexing Confederate muster rolls and the 1860 U.S. Census, there are some basic tools now available online that will allow anyone to at least get a general sense of the validity of his numbers. The Historical Census Browser from the University of Virginia Library allows users to compile, sort and visualize data from U.S. Censuses from 1790 to 1960. For Glatthaar’s purposes and ours, the 1860 census, taken a few months before the outbreak of the war, is crucial. It records basic data about the free population, including names, sex, approximate age, occupation and value of real and personal property of each person in a household. A second, separate schedule records the name of each slaveholder and lists the slave he or she owns. Each slave is listed by sex and age; names were not recorded. The data in the UofV online system can be broken down either by state or counties within a state, and make it possible to compare one data element (e.g., households) with another (slaveholders) and calculate the proportions between them.

In the vast majority of cases, each household (termed a “family” in the 1860 document, even when the group consisted of unrelated people living in the same residence) that owned slaves had only one slaveholder listed, the head of the household. It is thus possible to compare the number of slaveholders in a given state to the numbers of families/households, and get a rough estimation of the proportion of free households that owned at least one slave. The numbers varies considerably, ranging from (roughly) 1 in 5 in Arkansas to nearly 1 in 2 in Mississippi and South Carolina. In the eleven states that formed the Confederacy, there were in aggregate just over 1 million free households, which between them represented 316,632 slaveholders—meaning that somewhere between one-quarter and one-third of households in the Confederate States counted among its assets at least one human being.

The UofV system also makes it possible to generate maps that show graphically the proportion of slaveholding households in a given county. This is particularly useful in revealing political divisions or disputes within a state, although it takes some practice with the online query system to generate maps properly. Here are county maps for all eleven Confederate states, with the estimated proportion of slaveholding families indicated in green — a darker color indicates a higher density: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, All States.

Observers will note that the incidence of slaveholding was highest in agricultural lowlands, where rivers provided both transportation for bulk commodities and periodic floods that replenished the soil, and lowest in mountainous regions like Appalachia. The map of Virginia, in particular, goes a long way to explaining the breakup of that state during the war.

Obviously this calculation is not perfect. There are a couple of burbles in the data where populations are very low, for example Mississippi, where the census recorded two very sparsely-populated counties having more slaveholders than families (possible, but unlikely), or on the Texas frontier, where the data maps the finding that almost every family probably included a slaveholder. But in spite of its imperfections, it nonetheless presents a picture that more accurately describes the presence of slaveholding in the everyday lives – indeed, under the same roof – of citizens of the Confederate States than the much smaller number of slave owners does.

Aaron Perry, whose seven slaves are enumerated above in an excerpt from the 1860 U.S. Census Slave Schedule, illustrates the point. Perry, a Texas State Representative who raised hogs and corn in Limestone County (east of present-day Waco) had two sons, William and Mark (or Marcus), living with him at the farm at the time of the census. The elder Perry owned $3,000 worth of land, and nearly four times that in personal property, most of which must have been represented in those seven slaves. When the war came, both sons joined the Eighth Texas Cavalry, the famed Terry’s Rangers. Because neither of the sons – aged 21 and 17 respectively at the time of the census – held formal, legal title to a bondsman, Confederate apologists would claim that they are among the “ninety-eight percent of Texas Confederate soldiers [that] never owned a slave,” and, by implication, therefore had no interest or motivation to protect the “peculiar institution.” Nonetheless, it was slave labor that made their father’s farm (and their inheritance) a going concern. It was slave labor that, in one way or another, provided the food they ate, the shelter over their heads, the money in their pockets, the clothes they wore, and formed the basis of wealth they would inherit someday. And when they went to war, it was slave labor that made it possible for them to bring with them the mounts and sidearms that Texas cavalrymen were expected to provide for themselves. While the Perry boys left no record of their personal thoughts or motivations upon enlisting, the notion that these two young men must have had no interest, no personal stake, in the preservation of slavery as an institution is simply asinine on its face.

You don’t have to talk to a Confederate apologist long before you’ll be told that only a tiny fraction of butternuts owned slaves. (This is usually followed immediately by an assertion that the speaker’s own Confederate ancestors never owned slaves, either.) The number ascribed to Confederate soldiers as a whole varies—two percent, five percent—but the message is always the same, that those men 150 years had nothing to do with the peculiar institution, they had no stake in it, and that it certainly played no role whatever in their personal motivations or in the Confederacy’s goals in the war. But such a blanket disassociation between Confederate soldiers and the “peculiar institution” is simply not true in any meaningful way. Slave labor was as much a part of life in the antebellum South as heat in the summer and hog-killing time in the late fall. Southerners who didn’t own slaves could not but avoid coming in regular, frequent contact with the institution. They hired out others’ slaves for temporary work. They did business with slaveholders, bought from or sold to them. They utilized the products of others’ slaves’ labor. They traveled roads and lived behind levees built by slaves. Southerners across the Confederacy, from Texas to Florida to Virginia, civilian and soldier alike, were awash in the institution of slavery. They were up to their necks in it. They swam in it, and no amount of willful denial can change that.

Coming up: Did non-slaveholding Southerners have a stake in fighting to defend the “peculiar institution?”

_____________________

Images: Top, list of seven slaves belonging to Texas State Representative Aaron Perry of Limestone County, Texas, from the 1860 U.S. Census slave schedules, via Ancestry. Below, central image on the face of a Confederate States of America $100 note,issued at Richmond in 1862, featuring African Americans working in the field, via The Daily Omnivore Blog.

This post is adapted from one originally appearing in The Atlantic online in August 2010.

Nicely done. Case closed. It’s amazing how often that fact is trotted out (that only 10% or whatever of CSA soldiers owned slaves). It serves a political or emotional purpose, out of all context. How disingenuous to say the son of a slaveholder “doesn’t own slaves” just because the property is in the name of the head of the household.

Likewise, people — often the same people — are fond of claiming that the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation did not free a single slave. Huh? In fact it immediately freed 10s or 100s of thousands of them who had fled to Union lines, and encouraged others to do the same.

Thanks. But the core ideas here, that slaveholding families/households are (1) the better metric and (2) easily shown, have been argued many times. So it’s not remotely original to me.

I just thought it needed saying. Again.

Yes, McPherson laid it out in 1988’s “Battle Cry of Freedom” — that between a 1/4 and a 1/3 of households owned slaves — and that was a synthesis of well-used sources. It doesn’t matter to the True Believers.

Do you think Orly Taitz is going to give up her Birther Quest? Not a chance — now she’s more convinced than ever that the fix is in. Likewise, the Brothers Kennedy are not going to be swayed by any of this stuff. They’ve assembled their arguments and are done digging. Their version just “makes sense” to them, and that’s good enough.

There was a segment tonight on Lawrence O’Donnell’s MSNBC show (Chris Hayes guest-hosting) about the behavioral science of conspiracy theories. It was ostensibly about the Birfers, but it’s applicable elsewhere.

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/21134540/vp/42809364#42809364

“Likewise, people — often the same people — are fond of claiming that the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation did not free a single slave.” Yes. And the same people would claim that the US became an independent country on July 4, 1776. It did not — there were 7 long years before that became a reality. But within 2 1/2 years from the EP, all the slaves were free.

Foner’s Fiery Trial includes an Emancipation Proclamation map that I’d never seen presented before, showing where and how it took effect. The EP did free some slaves in specific areas, in the Florida Keys, along the Atlantic seaboard, and a stretch of the Mississippi. I’ve seen estimates elsewhere of around 50,000 slaves freed immediately upon the EP going into effect. A very tiny part of the whole, to be sure, but certainly not nothing, either.

Here’s the map, just because it’s a great tool; if the copyright SWAT team from W. W. Norton comes and kicks in the door, I’m counting on you guys to bail me out.

Ones father and mother may own a car but untill the child buys one they do not own a car. I simular manor a Southerner’s family may have owned one or multidtudes of of humans but the child did not.

The child may not own the car, but the child uses the car, benefits from the car, rides in the car, eats groceries carried home int he car, gets dropped off at school in the car, almost every day. If the family lost that car, that would have an important and negative impact on that child’s day-to-day life, along with everyone else in the family.

Even non-slaveholders benefited from the “peculiar institution.” Non-slaveholders hired slaves from their owners to work on specific projects. Steamboats hired slaves to work as firemen. Public works of all sorts — roads, levees, public buildings, railroads — were built with slave labor.

My point with this post is to show that the influence and effect of slaveholding extends far beyond the individual who actually held formal, legal title to that slave. This is really not a difficult concept.

all of that may be taken into consideration however the analogy is still valid. As a child I did ride in my parents car, food was brought home in the car, these were things not of my choosing and I had no control over the car or to what uses it was put, in like manor the child of slaveholders had no choice in the use of slaves. According to the U.S. Census of 1860 about 25% or one in every four households, in the South owned slaves and about 7% of Confederate soldiers owned slaves and according to the same U.S. census 2% of free Southern blacks owned slaves in 1860. That slavery was a pervasive institution in the South of the 1860’s is not at question, nor is the question that others in the South may have benefited from that institution. The question was as I understood it that 98% of the Confederate soldiers did not own slaves, I can attest to that at least in part, as my great grandfather on my mothers side was a Confederate soldier and he didn’t own not even one slave, still he enlisted and served in a Georgia regiment fought against Sherman at Atlanta and died of camp fever in Florida…

Thanks for your reply. You wrote:

The point of my post is to show that it’s a misleading question to begin with, one that papers over the central role that slavery held in the states that would form the Confederacy. Simple legal title is the wrong way to understand this.

Interestingly, you don’t have to be a “politically correct revisionist” to make this argument; James DeBow, editor of DeBow’s Review and a staunch apologist for slavery, made it in January 1861 as part of an essay arguing that all (white) Southerners should fight to defend slavery. He pointed out that counting all members of a slaveowning household as slaveowners greatly increased their proportion, and then went on to point out that even non-slaveowners had an interest in slavery, as it gave them someone to feel superior to.

http://gathkinsons.net/sesqui/?p=1940

Good stuff Andy. Really good stuff. This point may not be original to you – but the timeliness of your argument and the elegance of your presentation makes you one of a kind. I’m just so pleased that I was able to find this blog in the cacaphony that represents modern discourse. Thanks.

Top notch work Andy.

I just fiddled around with the UVA data bank for a minute (sadly busy today, and dont have more time to figure it out myself). I’m interested specifically in the slaveholding household breakdown of Maryland at the time.

As you know I recently made my way to Antietam (highly recommended to anyone reading here, btw – great battlefiled preservation), and knowing the lay of the land in MD, VA and WVa, I was struck by the misguided CSA expectations that Marylanders would have welcomed them with open arms in this area. As McPhereson notes in “Antietam, Crossroads of Freedom”, the cold reception they received was the first blow of the CSA’s Maryland campaign. Western MD is not the Eastern Shore of MD (aka the South), and different still from central MD. Driving through the country of western MD it is readily apparent that this is *not* plantation country.

I’d like to see the county-by-county breakdown in MD to see if the numbers back up my impression. Alas, I’m asking you to post another link to the UVA numbers since I’m forced to do “paying work” today instead. Much appreciated.

Hey, JimmyD. Hope the new practice and the new family member are both well.

Reply to this with your e-mail address and I’ll send you some related material. Comments are moderated, so it won’t be public.

“All for Slavery!” Right?

“Unionists of all descriptions, both those who became Confederates and those who did not, considered the proclamation calling for seventy-five thousand troops ‘disastrous.’ Having consulted personally with Lincoln in March, Congressman Horace Maynard, the unconditional Unionist and future Republican from East Tennessee, felt assured that the administration would pursue a peaceful policy. Soon after April 15, a dismayed Maynard reported that ‘the President’s extraordinary proclamation’ had unleashed ‘a tornado of excitement that seems likely to sweep us all away.’ Men who had ‘heretofore been cool, firm and Union loving’ had become ‘perfectly wild’ and were ‘aroused to a frenzy of passion.’ For what purpose, they asked, could such an army be wanted ‘but to invade, overrun and subjugate the Southern states.’ The growing war spirit in the North further convinced southerners that they would have to ‘fight for our hearthstones and the security of home.’ ”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tennessee_in_the_American_Civil_War

Tennessee vote prior to Fort Sumter and Lincoln’s call for troops to invade the South-

Vote for Convention Delegates (February 1861)

Pro-Secession 22,749 (20%)

Unionist (or “Cooperationist”) 88,803 (80%)

…and they voted against having a convention.

And after-

Referendum on separation from the United States (June 1861)

For 104,913 (69%)

Against 47,238 (31%)

Thanks for commenting, BR. I hope you and yours came through the storms all right.

You wrote: ““All for Slavery!” Right?”

As usual, you caricature what I wrote in the most simplistic way possible, and then argue against that straw man of your own creation.

Individual soldiers were (and are) motivated by many things, and often by things that they themselves cannot fully articulate. There are numerous studies that have explored this question in detail, including McPherson’s For Cause and Comrade and (dealing specifically with slavery) Manning’s What this Cruel War was Over. It’s complicated stuff, but my point here is that the common assertions that rank-in-file Confederate soldiers had no connection to, or interaction with, the institution of slavery, is demonstrably wrong.

I use Aaron Perry as an example, intentionally. He was a slaveholder, a state legislator, and voted to approve the secession convention that ultimately took Texas out of the Union. Two of his sons subsequently served in the Eighth Texas Cavalry, Terry’s Rangers. But because they didn’t hold legal title to slaves in their own names — they were 21 and 17 years old, living on the family farm at the time of the 1860 census — the Southron Heritage folks would argue (as with the Texas Senate resolution) that those two young men had no interest in slavery as an institution (financial or otherwise), and weren’t connected to it. That’s an asinine assertion on its face.

Roughly a quarter of the free families in Tennessee were slaveholders, a bit less than in the Confederacy overall. Here’s a map showing the proportional concentration of slaveholders in that state. How does that compare with the votes for secession?

http://onslowcountyconfederates.wordpress.com/wolf-pitt/

I find it interesting to combine the 1860 census and 1860 slave census. Also, looking at who holds the wealth in land and money. There is no doubt that the cause of the war was slavery, or more accuractely the cause was power and greed. In the south power and wealth was obtained by slavery. The center of commerce and wealth centered on the plantation, there was no escaping that regardless of your views on slavery. When I look at the officiers down to the sgts in my area of interest they are almost always from slaveholding families.

One of my interest is in those men who did not come from slaveholding families. There are whole libraries written about the slave master and his slaves but a significant group of people are left out of the story, and thats not by accident.

I thought alot about why southern men fought as I traveled the mountains of NC and Tennessee this week. There sure are alot of rebel flags flying up in those mountains.

Richard, thanks for commenting. I’m going to be following up with some of what was being said at the time about non-slaveholders’ interests in maintaining the system.

One of the primary reasons that some white Southerners agitated for the reopening of the African slave-trade was that in the 1850s slave prices soared to speculative levels. The advocates worried that with prices so high, non-slave owning whites would lose all hope that they or, even more so, their descendents, could never hope to be able to afford to buy even 1 slave. The advocates feared, because of this, that a schism would develop between slaveowning and non-slaveowning whites. The advocates figured that Africans would be cheaper, more manageable (not speaking the language, etc) than US born slaves. They lost, in no small part because of the absolute opposition of states such as Virginia that were major exporters in the internal trade and who had no intention of having to compete with cheap foreign imports.

I’m working on an upcoming post on what was being said at the time about non-slaveholders’ interests in protecting the institution. While one can argue (as many do) that one’s Confederate great-great-granddaddy had no interest in preserving slavery because he himself owned no slaves, there were plenty of prominent folks in the South in 1860-61 willing to explain why this was not correct.

Here’s a graph that shows the skyrocketing value of slave in the antebellum decades. This shows the aggregate value, so reflects both increases in prices and increase in population. Note the spike in the wake of the Panic of 1837, where the value of slaves increased as the value of the currency dropped.

When I lived in Knoxville, Tenn., the local legend was that East Tennessee was that in order to rig the vote at the convention to join the confederacy, saboteurs blew up rail lines to prevent pro-Union delegates from the eastern counties from traveling to Nashville and keeping Tennessee in the USA.

That’s a local legend and I don’t have a citation to authority for it. It is clear that in the statewide referendum on secession, West Tennessee stayed both pro-slavery and voted for secession, East Tennessee stayed anti-slavery and voted for union, and it was Middle Tennessee that swung. Citizen representatives and elected county officials of twenty-six counties in East Tennessee met in Greeneville and Knoxville after the June referendum and voted to secede from Tennessee and be part of the USA.

Now, clearly the events at Fort Sumter changed the minds of fickle-to-this-day Nashvillians. But the real question here seems to be was the pro-unionism of East Tennessee merely a coincidence of its relatively low economic reliance upon and social integration of slavery? Well, it seems quite harmonious with West Virginia’s secession from Virginia and petition for re-integration into the USA as a separate state — you’ll note the low incidence of slavery in the mountainous counties of West Virginia as compared with the farmlands east of the Appalachians.

It’s remarkable that pretty much wherever there was a lot of slavery, there was a lot of political sentiment for seccession, and where there wasn’t a lot of slavery, there was a lot of political resistance to seccession. Correllation does not necessarily imply causation, I know, but in this case, it seems a fair linkage to make.

Burt, thanks for commenting. You wrote:

There is a linkage, which I’ll deal with (specifically with Texas) in an upcoming post.

The mountains of North Carolina/Tennessee have a rich Civil War history. The story of Russel Gregory and his family in Cades Cove comes to mind. His tombstone reads:

Russell Gregory

1795-1864

Founder of Gregory’s Bald About 1830

Murdered by North Carolina Rebels

or

William Holland Thomas of Cherokee

http://cwmonuments.wordpress.com/2011/04/29/william-holland-thomas/

I linked up with this via “The League,” and boy am I glad I did. Great blog!

Thanks. There’s lots to discuss.

This whole blog has been wonderful. Thank you Andy. However I agree with you completely; we ain’t about to convert these folk by holding out facts; they will come back to the 98% story no matter what. A really good book on both Union and Confederate reasons for fighting (and I don’t know why I have not seen in referenced more often, except that it was written by a woman) is What This Cruel War Was Over by Chandra Manning, Random House, 2007. She went thru f Camp/Regmt Newspapers indexing reasons. I love this quote “The fact that slavery is the sole undeniable cause of this infamous rebellion, that it is a war of, by, and for Slavery, is as plain as the noon-day sun” (p. 3, quoting from the 13th Wisconsin Inf, Feb, 1862)

yes Jeff it is as plain as the noon day sun. All one need do is to read the “Articles od secession” to see that Georgia was as plane as can be in stating that the question of slavery was their reason for leaving the Union the remainder were just as clear. Slavery was at the core of the war

Rastis I am 67 years old , i have never meet a slave and ninety nine and 99/100 % of blacks has never meet a slave . My point is if we don’t get our heads out of our mess kits , and focus on today we all will be slaves .

I suppose that this thread is too old for my input to have any impact at all. However, here goes. One hundred and fifty years from now, a researcher reading manuscripts from FOX network broadcasts would perceive a different reality than another researcher reading manuscripts from CNN or NPR. Reports written on the same day contradict each other in regards to both the facts themselves and interpretations of the facts.

I am 55 years old and grew up in Birmingham Alabama. My great great grandfather owned a sizeable farm in Marion County where he owned a handful of slaves. He, like the majority of people in our area, was opposed to succession. Our pioneer ancestors were Revolutionary War veterans, veterans of the War of 1812, and the Indian Wars. They were reluctant to take up arms against their country. My great great grandfather ran a sort of “underground railway” funneling Alabama Unionists over the Mississippi and Tennessee lines to join the Union army. When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, he gathered his slaves and told them what the President had done. He told them that they were free to leave or that they could stay on and be paid wages like any other free worker.

I had another great great grandfather who was also a Unionist. His two sons were conscripted into the Confederate army. When they became sick up in Tennessee, my great great grandfather went after them. He convinced the officers to grant his boys furloughs to return home and get well. They never returned to the southern army. They did not own slaves. Their father did not own slaves. They did not voluntarily join the confederate army. They did not join the northern army. However, they actively resisted the southern cause.

I had yet another great grandfather who fought under Nathan Bedford Forrest in the cavalry, serving in Tennessee and north Alabama. His three daughters later married three sons of a neighbor who had served in the 1st Alabama Cavalry…USA. He had a young cousin who also served in the 1st Alabama USA. During the war, the youth was captured by the home guard while he had come home to see his wife. He was hung up like pig and skinned alive for his service to the Union.

My wife’s great great grandfather was a native of Winston County. He died of measles in a military hospital in Memphis while serving in the Union army. He had three brothers who also fought for the Union. Three of the four brothers died during the war.

In the years after the war, during the horrors of reconstruction, it became difficult and even dangerous to admit service for the Union. The stories recounted above were almost lost to history. The vast majority of people in Alabama (and throughout the nation) have no idea that much of north Alabama was pro-Union. We tend to paint this state with the broadest of brushes. The search for absolute truth is always elusive. It is well nigh impossible when a war is involved. I do not know what the whole story is, but this is my story. Thanks so much for this forum.

Thank you Mr. Tucker.

Although I can’t say that my family history held any loyalty to the Union during this horrible conflict, I do thank you for providing a glimpse into the contradictory experiences of those Southerner’s such as my ancestors from the “hill country” in the Deep South and those of the Deltas and Lowlands of the Deep South.

As all too few know or are willing to acknowledge, it was a vastly different experience. One not filled with generational farming wealth and land ownership but with wood cutting and sharecropping all of their own. A great historical and cultural disservice has been done to these men and women and their descendants who were not recipients of the benefits of the popularized Antebellum Southern Gentry.

That being said, this is very informative and insightful information with a great deal of truth and I greatly appreciate the author’s efforts. I would like to know the socioeconomic background of the author if that is possible.

I didn’t see this post when you originally posted it, great read. The numbers do not lie. BUT, you forgot to mention the other ridiculous counter argument to slave numbers in the South, Andy.

Let’s focus on the United States, and how many families owned slaves in the North. Ya know, because, slavery was legal in the North and therefore not the reason the war was fought.

I kid. Great post!

The folks who claim that some tiny proportion — four percent, six percent, whatever — of white Southerners were slaveholders would have you believe that Scarlett O’Hara, who never saw a day in her life prior to 1864 that she wasn’t being cared for/waited on/provided for by enslaved persons doesn’t count as a slaveholder, and so had no personal interest in preserving the institution. It’s ludicrous on its face.

Ha ha!. Very true. I’ve got to remember that one for later.

As for slaves in “the north,” next time someone says that, ask them to estimate how many slaves there were in the Union states, excluding the border states of Missouri, Kentucky and Maryland. The correct answer is around 1,800, fewer than the student population of many modern high schools.

I know, I just think it’s a ridiculous deflection. Rather than focus on the ills of the past they blindly defend, these people would rather misdirect you into talking about someone else’s issues.

Lately I had someone trying to claim that most slaves were owned by northerner absentee landlords. He stated that the census proves him right. So I linked the 1860 census up and asked him to point those landlords out. I’m still waiting.

What I don’t understand is how people honestly believe that is a counter argument to begin with. Northern slave ownership prior to the firing on Ft. Sumter does not tell us anything about why the South chose to secede and fight.

It’s just muddled thinking.

Low and behold, George made a comment that I am actually interested in.

What are the number of Officers that fought fought for the North, who owned slaves? I would be interested to know how many of that number are Southerners as well. Granted, I know they believe this is another deflection to “prove” the war was not about slavery, but I think it would be an interesting fact to know nonetheless.

I’m sure that someone has published that. George is always touting his own skill at rooting out relevant “facts” about the war, so perhaps he’ll get right on that. I’m honestly not impressed with folks who demand others answer a question that they themselves are perfectly capable of finding themselves — it shows they’re trying to score argument points, not find the actual answer.

More generally, that’s one thing that I really have no patience with — folks who toss out rhetorical questions or vague claims when the actual answer is discoverable and knowable, with a little effort.

Well yea, but it is still a curious question. I Googled it a few times but nothing yet.

It’s a perfectly legitimate question, although I also believe that if the answer turned out to be more than zero George would swing it like a cudgel as “proof” that the war wasn’t about slavery.

As I say, if he’s serious and there’s not already research out there, George can use Glatthaar’s methodology and find his own answer.

Ha! Very true.

Many thanks Mr. Hall.

Being spaniard I’ve been always amazed how many people here in Spain believes the myths that the confederacy did not fought for slavery , that there were just a few wealthy slaveholders and not the common soldiers, and that the South fought for a “noble cause”. Blogs and works like yours help a lot dispelling these myths and I can point them here when discussing the facts.

Thank you very much.

The more I read about the antebellum South, the more I realize that I cannot possibly imagine what day-to-day life was like in a slave society: the totality of slavery reaching into virtually every aspect of one’s life, whether one owned slaves or not. That society’s values were inculcated into pretty much everyone. On the face of it, then, it seems perfectly reasonable that most young, white, poor (and not so poor), Southern boys at least supported slavery.

Mine is merely an assumption, although borne out by much of the contemporary literature. Your evidence here, Andy, is far more substantive, and goes farther, since it suggests that Southern boys *fought* for slavery. But my main point is that this gets into the “blind spot” all historians face: what was really going on in those people’s heads? What was it like, really, living in a slave society? I would imagine it was horrible–except if I was actually raised in it and knew nothing different, I probably would not think that at all.

Texas is a good place to try to understand the commitment of the slave society. The number of enslaved persons more than TRIPLED between the 1850 and 1860 U.S. censuses, primarily due to settlers relocating from other parts of the South to Texas, where good land was plentiful and cheap. (Perry came from Alabama a little earlier, in 1846, but for much the same reasons.) During that same 1850-60 period, the number of free African Americans actually decreased, to the point of being almost invisible — which was the point, really. Texas has been called “an empire for slavery,” for good reason. Because Texas — unlike the rest of the South — was starting effectively as a blank slate when it came to African slavery in the 1830s, so it developed a particularly raw, no-nonsense variant of the peculiar institution.

The folly of this analysis is mainly due to the omission of the cost of the slave. To say that all income within a household comes from the slave’s labor is as absurd as saying that a nanny today pays for herself and the remainder of household consumption when in fact a nanny requires an outlay of funds.

Other issues are the assumptions that all offspring will own slaves in the future which is false for at least some portion, and no accounting for the mortality rate of the slave owning heads of household which necessarily prevents straight additive incremental slaveholder rates.

But whether you believe the soldier’s ownership rate is 2% or 40%+, still the majority of soldiers did not own slaves. Btw, how do you reconcile the slaveholding border states fighting for the Union?

All this focus on slavery is a smokescreen as slavery pre-dates the Union and was a Constitutional right. The purpose is to hide the war crimes of invading the South at a human cost of 700K. That is the real tragedy given that slavery would have died shortly on it’s own without much or any bloodshed.

How would it have died out? Plus you continually neglect to address the fact that the slave owners chose to secede and start a war to protect slavery. Therefore you cannot say it would have died out. The slave owners refused to let that happen.

You ignore the issue of slavery for your own personal reasons. The facts are clear that slavery was the issue that led to the Civil War. The Northern states were acting within the Constitution while the southern states were not. The slave owners wanted a war and they got one. You may not like its outcome, but that’s history.

I don’t recall seeing any prominent Confederate claiming that chattel bondage was on on its way out, at least prior to 1865. It’s an ex post facto attempt to disassociate secession with the protection of the peculiar institution.

I agree with some of Jimmy’s statements such as powerful slaveholders started secession in order to protect the value of their slave assets. Of course, sister states domino-ed in response to invasion. Regarding the un-sustainability of slavery, we have only to look at the rest of the world to see that other countries which had slavery longer than the US had to acquiesce to abolition. A good discussion of this point is made in professor Robert J. Barro’s book, Getting It Right: Markets and Choices in a Free Society.

And I agree with Andy in that no prominent Confederate argued for slavery’s demise as it would not have been in many of their economic interests; however, we do see Patrick Cleburne and 13 of his officers as well as Lee at the very end attempt to continue their fight for independence by suggesting recruiting blacks as soldiers. Of course, this didn’t fly among the staunchly pro-slavery government.

But I disagree that this is an attempt to disassociate secession with slavery, rather that slavery would have been abolished at some point, most likely before the 20th century if other nations are an indicator. Am I wrong to think that this would have been at least a possibility?

One can make a “what would have happened” scenario about anything. Glenn LaFantasie did one a few years ago in which the Confederacy won its independence and, over the following 150 years, re-joined the United States and brought us all right back (more or less) to where we are today. His point was that you can make anything happen when you play what-if. It isn’t real.

I prefer Harry Turtledove’s multivolume exploration of the concept via alternate history. Since Turtledove has a Ph.D in history (and makes a lot more money writing fiction than he ever would writing actual history) his books are interesting. The key point is that they are complete works of fiction. Take a look at How Few Remain and the whole series.

The key is that to speculate upon what if questions is pointless as we don’t work in a what if universe. History is the story of what did happen in the past, not what might have. Slavery ended in the US as the result of the Civil War. The slave owners made a choice about what to do about slavery. Yes, there were alternatives, but the reality is that they made a choice and that is the history that occurred. Yes, they should have made a better choice, but they acted within their framework of reality, their interests, and their beliefs. It was the ultimate bad decision, but it was the one they made. So that’s what we study and that’s what we explain to students.

“Slavery would have died on its own anyway” is a common trope, but there’s little real evidence to support that. The number of slaves increased in every single census from 1790 to 1860. That’s not a condition on the decline. More than half the population of South Carolina was enslaved. It was a going concern.

I liked his “Lee at the Alamo.” He changed certain facts and characters to improve the story, but it’s well done.

http://www.tor.com/stories/2011/09/lee-at-the-alamo

I think that history can be used as a model to drive future policy. The Barro book stated the fact that over twenty nations abolished slavery, all but two without violence. The important thing for me to take away from the war is that an invasion was responsible for massive casualties.

Actually NPR had a segment this week on the 35 remaining living children of CW veterans. They all said the same thing in that their fathers had reconciled and held a grudge no longer. Perhaps that is the take away.

You may mean Charles Kelly Barrow. Yes, that’s a claim I’ve heard but it’s not correct. Armed conflict is more the norm than otherwise, in this hemisphere. Multiple nations (e.g., Mexico) abolished chattel bondage in the 1810s and 1820s as part of their overthrow of Spanish colonial regimes, and those tended to be very bloody. Those conflicts are not generally thought of as being “about slavery,” but that was nonetheless part of the mix and (more important) the outcome of those wars.

Brazil is sometimes cited as an example of a slaveholding nation that did away with slavery peacefully in 1887, but that ignores a along history of violent slave uprisings in that country, and the fact that by 1887 only about 15% of the population was enslaved. By contrast, over half the persons living in South Carolina and Mississippi in 1860 were slaves. Also re: Brazil, keep in mind that several historians have pointed to the existence of slavery and the presence of cotton cultivation as the reason a large number of southerners (so-called Confederados) relocated to Brazil after the war, as opposed to any of a dozen other countries.

That’s a very important point. That’s also why I have complete and utter disdain for modern-day, make-believe Confederates whose idea of “protecting their heritage” is whipping up anger and resentment in 2014 about events — sometimes real, but often exaggerated or entirely fictional — that happened to people they never knew. It’s both deliberate and phony, and their Confederate ancestors, who by and large learned to reconcile and not live out the rest of their lives in anger, would be embarrassed by the foolishness their descendants are perpetrating today in their names.

Can you you name one country that explicitly legalizes slavery in the 20th century or today? Point is slavery would have vanished and only in the US and Haiti was it done by violence. The human cost of invasion should be the focus of the CW.

Btw have you read Eugene Datell’s book, Cotton in a Global Economy? The value of slavery was driven by the world demand for and technological advances of cotton production. Northern manufacturing knew it, England knew it, but it is strangely absent from detractors of southern commemoration.

“Only in the US and Haiti was it done by violence.”

As has been pointed out previously, this is untrue.

“The human cost of invasion should be the focus of the CW.”

You ignore the human cost of slavery. What is the moral and human measure of one of two more generations of MILLIONS of persons held in chattel bondage, Jack? One or two more generations of slave auctions? Those have a price, too, but you want to stack one side of the scale with nothing on the other.

“Have you read Eugene Datell’s book, Cotton in a Global Economy?”

It’s not a book, it’s an online essay, and the author’s name is Dattel. Get it right if you’re going to cite him. His arguments are not “strangely absent” from others’ discussions. Northern and European industry certainly depended on cotton, but the events of 1861-65 show pretty conclusively that they were not commited to chattel bondage in the way that the South explicitly said it was.

Andy I was thinking of Dattell’s Cotton and Race in the Making of America, not just the essay. Basically, slavery’s fate was entwined with the value of cotton.

Regarding the human cost of slavery, you would have to weigh it against the deaths resulting from the murderous invasion of the South. Most would agree that abolition over time without major loss of blood and property would have been optimal. Otherwise you could quantify the loss of life from slavery and compare, but I haven’t seen that.

And I meant Robert Barro earlier as his book Getting It Right: Markets and Choices in a Free Society clearly states the advantages of not going to war as slavery would have died out shortly.

“Otherwise you could quantify the loss of life from slavery and compare, but I haven’t seen that.”

There is a real moral and human cost to enslavement, beyond counting up actual deaths. You continue to ignore that.

It would be nice if chattel bondage in the United States could have been ended without a bloody war. But in the end, that’s what it took, all the bloodier for the tenacity with which the Confederacy fought to protect it.

If Jack really wants to learn, then he needs to take Foner’s EdX courses on this issue. I don’t hold out much hope for him to do so as it seems most of the neo-confederates have dropped out of the first course and are not in the second one. Foner’s presentations are on the money and the neos just can’t deal with it. Neos aren’t used to being ignored and countered with facts while at the same time having their made up trash called out for what it is: a lie.

Of course they get that treatment on several blogs which makes me think they have a penchant for intellectual suffering.

What is a “neo-Confederate”? You sound really mad as if someone challenged your conceited views.

“The neo-Confederate school of thought. . . is convinced that Northerners are damnyankees, and that they ought to stop ‘meddling’ in Southern affairs.”

— Richmond Times Dispatch, January 27, 1934, p. 8.

Sounds about right.