Oh, About that Black Confederate at Arlington. . . .

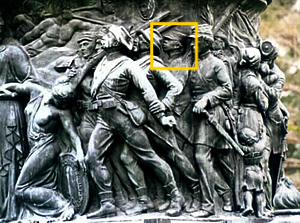

One of the oft-cited elements in discussion of Black Confederates is the inclusion of an African American figure (left) in the frieze encircling the Confederate Monument at Arlington National Cemetery. The monument, funded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and dedicated in 1914, includes around its base a bronze tableau of Confederate soldiers marching off to war, answering their nation’s call. The young black man, wearing a kepi, marches alongside a group of soldiers; the others are armed but the African American carries no visible weapon. Nonetheless, his presence among the soldiers is usually presented as prima facie evidence that African Americans, too, were enlisted as soldiers in the Confederate Army. He’s cited on multiple websites, such as here, here, here, here and here; a web search on the phrases “Black Confederate” and “Arlington” generates several thousand hits. This descripti0n, on the blog of the California Division of the SCV is typical:

One of the oft-cited elements in discussion of Black Confederates is the inclusion of an African American figure (left) in the frieze encircling the Confederate Monument at Arlington National Cemetery. The monument, funded by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and dedicated in 1914, includes around its base a bronze tableau of Confederate soldiers marching off to war, answering their nation’s call. The young black man, wearing a kepi, marches alongside a group of soldiers; the others are armed but the African American carries no visible weapon. Nonetheless, his presence among the soldiers is usually presented as prima facie evidence that African Americans, too, were enlisted as soldiers in the Confederate Army. He’s cited on multiple websites, such as here, here, here, here and here; a web search on the phrases “Black Confederate” and “Arlington” generates several thousand hits. This descripti0n, on the blog of the California Division of the SCV is typical:

Black Confederate soldier depicted marching in rank with white Confederate soldiers. This is taken from the Confederate monument at Arlington National Cemetery. Designed by Moses Ezekiel, a Jewish Confederate, and erected in 1914. Ezekiel depicted the Confederate Army as he himself witnessed. As such, it is perhaps the first monument honoring a black American soldier.

Sounds pretty convincing. Too bad it’s not, you know, true. As James W. Loewen and Edward H. Sebesta point out in their recent anthology, The Confederate and Neo-Confederate Reader, the booklet published by the United Daughters of the Confederacy at the time of the monument’s dedication gives an entirely different identification. Going back to that original text, it is detailed and explicit:

But our sculptor, who is writing history in bronze, also pictures the South in another attitude, the South as she was in 1861-1865. For decades she had been contending for her constitutional rights, before popular assemblies, in Congress, and in the courts. Here in the forefront of the memorial she is depicted as a beautiful woman, sinking down almost helpless, still holding her shield with “The Constitution” written upon it, the full-panoplied Minerva, the Goddess of War and of Wisdom, compassionately upholding her. In the rear, and beyond the mountains, the Spirits of Avar are blowing their trumpets, turning them in every direction to call the sons and daughters of the South to the aid of their struggling mother. The Furies of War also appear in the background, one with the terrific hair of a Gordon, another in funereal drapery upholding a cinerary urn.

Then the sons and daughters of the South are seen coming from every direction. The manner in which they crowd enthusiastically upon each other is one of the most impressive features of this colossal work. There they come, representing every branch of the service, and in proper garb; soldiers, sailors, sappers and miners, all typified. On the right is a faithful negro body-servant following his young master, Mr. Thomas Nelson Page’s realistic “Marse Chan” over again.

The artist had grown up, like Page, in that embattled old Virginia where “Marse Chan” was so often enacted.

And there is another story told here, illustrating the kindly relations that existed all over the South between the master and the slave — a story that can not be too often repeated to generations in which “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” survives and is still manufacturing false ideas as to the South and slavery in the “fifties.” The astonishing fidelity of the slaves everywhere during the war to the wives and children of those who were absent in the army was convincing proof of the kindly relations between master and slave in the old South. One leading purpose of the U. D. C. is to correct history. Ezekiel is here writing it for them, in characters that will tell their story to generation after generation. Still to the right of the young soldier and his body-servant is an officer, kissing his child in the arms of an old negro “mammy.” Another child holds on to the skirts of “mammy” and is crying, perhaps without knowing why.

My emphasis. “Faithful negro [sic.] body servant” is not a soldier under arms. But it is consistent with the “loyal slave” meme — or “astonishing fidelity,” as the monument’s description calls it — so central to the Lost Cause during those years; similar sentiments appeared on monuments throughout the South.

The comparison to “Marse Chan” further reinforces the theme. “Marse Chan” was a short story by Thomas Nelson Page (1853-1922), that first appeared in Century Magazine in 1884. Nominally set in 1872, “Marse Chan” is told in flashback through the eyes of Sam, a young slave in antebellum Virginia who is assigned as body servant to his master’s son, Tom Channing. Tom grows up and, when the war comes, Sam follows his young master into the army, describing his assignment in the dialect-style of writing commonly used by white authors of the period when writing dialogue for black characters: “an’ I went wid Marse Chan an’ clean he boots, an’ look arfter de tent, an’ tek keer o’ him an’ de hosses.” A contemporary classic of Lost Cause fiction, “Marse Chan” was Page’s best-known work. It would have been familiar to those attending the dedication, who would have understood exactly how its protagonist was the literary parallel of the figure in bronze.

The figure on the monument doesn’t represent a soldier, but it wouldn’t matter much as historical documentation if it did; had the sculptor, Moses Ezekiel, depicted the man explicitly as a soldier, it would reveal only that thought it important to include as part of the story he wanted to present — not necessarily that such men were commonplace. Those claiming the figure as “evidence” of African American soldiers in Confederate ranks a half-century prior to the monument’s unveiling make the common era of assuming that the memorial represents history as it actually was. In fact, no memorial does that; rather, they reflect the story and impressions that their sponsors and artisans want to be remembered, and depict the past in a particular way. Some monuments are more objectively accurate than others, but none is without its bias.

The rush to point to the figure on the Arlington memorial is, sadly, typical of the “scholarship” that informs much of the advocacy for Black Confederates. It reflects a sort of grade-school literalism; there’s a black figure in among the soldiers, therefore this man was a soldier, therefore this is proof of African Americans in the ranks of the Confederate Army more generally. The truth, of course, is not quite so obvious, but revealing it requires taking time to go back to the primary sources and giving some consideration to the context of the time of the monument — 1914, that is, not 1861-65 — and the preferred interpretation of the monument’s sponsors, the UDC. Once you understand those things, and not before, you can start looking for meanings and evidence contained within.

_____________

Additional, October 28: Stan Cohen and Keith Gibson’s Moses Ezekiel: Civil War Soldier, Renowned Sculptor reveals no further information about his design process or his own views on the Confederate Monument at Arlington; it simply repeats the description in the official UDC booklet. Ezekiel also completed statues of Thomas Jefferson for the University of Virginia and of Stonewall Jackson on the parade ground at VMI. It’s beautiful little book, highly recommended.

In a sense its fitting that the depiction of the faithful black servant is used as an example of a black confederate soldier, since both are really the same idea; black people were content in their subordinate position.

They loved each other the black slave and the white master, they just had really strange ways of showing it.

Exactlly. Black Confederates are essentially the old “loyal slave” theme, seasoned with a dose of self-empowerment to appeal to a modern audience.

Significantly, almost every site where I saw the (usually word-for-word) description of the figure on the monument as a soldier also goes out of its way to mention that the sculptor, Mose Ezekiel, was Jewish, even though they say almost nothing else about him. After the third of fourth time, it really does begin to have a whiff of, “I can’t be a bigot; why, some of my best friends are _______.”

A very nice piece of research.

Andy,

I second the comment by Brooks…very nice piece of research. Just goes to show what happens when someone does their homework.

Corey and Brooks (and Kevin): Credit where it’s due: the cite to the original monument dedication booklet identifying the figure as a body servant appears in Loewen and Sebesta’s Confederate and Neoconfederate Reader. Starting with that, I tracked down the full text and found it to much more explicit than a passing reference. So that was the critical nugget that was the genesis of the post.

The quote appears to be the writer’s own personal interpretation of the monument.

Most blacks attached to the Confederate armies were servants (+/-90%) so that interpretation can be made…but are you saying there were no black Confederate soldiers and therefore no one is allowed to make that interpretation?

What did Moses Ezekiel have to say about it? Was it his intent to depict a servant or a soldier?

Col. Herbert was Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Arlington Confederate Monument Association, writing for a booklet published by the UDC, the monument’s sponsor, to commemorate the unveiling of the work. The author served as master of ceremonies and as a speaker at that event. It’s pretty implausible that, coming from that perspective, the author is going off on his own here and expressing views that differ significantly from that of the organization she represents.

If you want to argue that he was merely expressing her personal interpretation, as opposed to the intent and symbolism embraced by the UDC, you’re welcome to. But I don’t think you’ll find any contemporary evidence that the UDC endorsed the idea that African Americans served as soldiers in the Confederate army in significant numbers, or that they intended to convey that notion in the monument. One can speculate any number of scenarios, but the contemporary evidence is what it is — that the UDC chose to memorialize the “faithful Negro body-servant” rather than a soldier under arms. If you’ve found any contemporary documentation from the UDC (or UCV) to the contrary, please share it.

Thanks for taking time to comment.

(Minor edits 2/9/11 to correctly represent Herbert)

[…] the subject of “Black Confederates” at this time, and, in the CW blogosphere, I think Andy Hall and Kevin Levin are handling it just fine. I’ve engaged in discussion about the topic in this […]

[…] blog, precisely because of the research findings he shares. Several months ago Andy posted some very interesting information concerning the Confederate monument at Arlington Cemetery, effectively challenging arguments that […]

So there were Black Confederates and the numbers must have been staggering… I’ve heard 85,000 quoted by some…that might be accurate if most slave owners took their slaves into battle with them…

The numbers tossed around — 85,000, 90,000, whatever — are estimates based on guesses based on speculation. They’re really pretty meaningless.

Yes, thousands of African American slaves accompanied their masters (or the master’s sons) into the Confederate service, but they were not enlisted as soldiers, and they served their owners, not the Confederacy or the Confederate cause. There are anecdotes of some actually picking up a weapon when they found themselves in a tight spot, but they were never considered to be soldiers by actual Confederate soldiers themselves.

You might want to spend some time with old issues of the Confederate Veteran magazine (linked under the resources list at right) to see how real Confederates viewed these men. It’s very different from the tales being told today by make-believe Confederates.

I’m sure that you’ve seen this. What’s your thoughts on it???

http://www.npr.org/2011/08/07/138587202/after-years-of-research-confederate-daughter-arises

I remember reading that story at the time. Weary Clyburn’s wartime role has been gone over many times; he was an enslaved person and a body servant. His pension record makes that clear. Modern “black Confederate” advocacy very purposely elides over these distinctions, which were fundamental both during the war and in the decades after.

There’s this passage, which turns up frequently in modern “black Confederate” narratives:

I don’t know what Weary Clyburn’s actual views were at the time, but the he-went-willingly is a common explanation that sidesteps the coercive nature of his position — whether he wanted to go or wanted to stay, he really had no choice in the matter. To ignore that hard reality, and to focus on the “best friends” angle, makes one feel all warm and fuzzy, but it doesn’t move our understanding of history forward at all.

One other thing from the article:

This was by design. It’s not a bug, it’s a feature. The states that established pensions specifically for African Americans did so for personal servants who went to war with their masters, and not for general laborers who were hired out by their owners or conscripted to do that sort of work, even though must have been much more numerous, and (arguably) contributed more directly to the Confederate war effort through their work. (I’ve seen exactly one state pension awarded to an African American man who was conscripted to build fortifications; that was from the State of Texas, which appears never to have formally established a separate program for former slaves, but simply began allowing applications under the existing program around 1921.) If you go back and read the arguments made for awarding pensions to African American men (like this one in the Confederate Veteran Magazine), it’s made explicitly clear that those were intended to recognize service to their masters, rather than to the Confederate nation or military.

The commentary and analysis of the Confederate Memorial at Arlington by Messrs. Loewen and Sebesta would be more meaningful if contrasted with how and when the service of US Colored Troops was finally

recognized nationally. Would such recognition by the US government factually document the pervasive institutional racism the US Colored Troops were subjected to, including segregation, lesser pay and substandard uniforms and equipment, or would such recognition attempt to claim some moral high ground over their Confederate counterparts

Whether Blacks were actual soldiers or Body servants is less relevant than their motivation in supporting the Confederacy. It seems that in the case of Weary Clyburn’s wartime service, it is difficult for some to accept that a black slave could be the best friend of the white son of his master and serve of his own volition. Having met members of the Clyburn family, they are unwavering in their view that Weary followed his friend Frank voluntarily and was immensely proud of his Confederate Service. The terminology used to define his service does not in any way diminish his sacrifice and contribution.

The description of the African American figure on the monument at Arlington is not from Sebesta and Loewen — it’s directly from the official commemorative book, authored by the chairman of the committee that raised the funds and approved the design.

“Whether Blacks were actual soldiers or Body servants is less relevant than their motivation in supporting the Confederacy.”

If you can point me to a contemporary primary source describing Weary Clyburns’s, or Louis Nelson’s, or Dick Poplar’s “motivation,” please do so. What’s often attributed to them, and men like them, is usually based on oral tradition passed on through the generations, or modern speculation based on nothing at all.

Finally, if you see Brag Bowling, say hello for me and remind him that he never did send me that video of his and Richard Hines’ press conference that he said he would. It’s been more than two years now, and I’m still waiting to hear from him. If this goes on much longer I shall begin to doubt him.

What about the black veterans at the early confederate reunions? And there were those who did want to serve because they thought their loyalty would result in freedom when the South won. But why can’t we just honor all who served, regardless of side, color or status, and try once again for reconciliation? Why do we have to keep the old wounds open, seeking to say “our side” was right and the other side “wrong” so we can punish the other side. Seems to be the reconciliation so valued in 1898 is not desired by anyone today — it is all about further division, alienation and domination.

Thanks for taking time to comment. You’ll find that I’ve written quite a bit about African American men at Confederate reunions. If you go back and read what was written at the time, you’ll find that there was a real distinction made between the white veterans and the African American men, mostly former cooks and body servants, who participated with them. It’s a much more complicated relationship than a simple skimming of old photographs might suggest. We owe it to the past to be very clear about what was going on there.

http://blackconfederatesoldiers.com/home.html

I’m familiar with that site.

Andy you’re a fool. I’m not sure if its your white guilt or insistence that all white people must be wrong always. My Great grandfather was from Kentucky. He was one of Morgans raiders. I have in his own hand he deplored slavery. He wrote letters to my Great grandmother back and forth and the one thing that is VERY clear is they both thought slavery should be abolished. He fought to protect his land from invaders and died as a result. You and the rest of your Ilk keep shoving lies down our throats. You need to stop. Slavery is wrong, always has been. Free blacks fought for the confederacy. They were allowed to be officers, they were paid on an equal scale with whites, and they were not segregated. I refer to the words of the US Surgeon Generals of the Army of the Potomac and the report he mad post Antietam. “10% of the Army of the Northern Virginia were black.”

Here ya go:

“Wednesday, September 10: At 4 o’clock this morning the Rebel army began to move

from our town, (Fredrick, Md), Jackson’s forces taking the advance. The movement

continued until 8 o’clock pm, occupying 16 hours. The most liberal calculation could not

give them more than 64,000 men. Over 3,000 Negroes must be included in this number.

These were clad in all kinds of uniforms, not only in cast off or captured United States

uniforms, but in coats with Southern buttons, State buttons, etc. These were shabby, but

not shabbier or seedier than those worn by white men in the rebel ranks. Most of the

Negroes had arms, rifles, muskets, sabers, bowie knives, dirks, etc. They were supplied

with knapsacks, haversacks, canteens, etc and they were an integral portion of the

Southern Confederate army. They were seen riding on horses and mules, driving

wagons, riding on caissons, in ambulances, with the staff of generals and promiscuously

mixing it up with all the Rebel horde.” (Union Sanitation Commission Inspector Dr.

Louis Steiner, Sept. 1862.) https://archive.org/stream/reportlewissteiner00steirich/reportlewissteiner00steirich_djvu.txt

Are you going to be intelligent, or the typical liberal idiot and call me a racist?

I don’t know why people make the reason for the civil war so complicated. It was about state rights and the principal state rights at issue had to do with slavery. Slavery was a state right at the time and, by the way, President Lincoln supported the state right of slavery at the start of the war.

The south also had a credible legal and political argument on state rights. For example, the Constitution says nothing about the duration of the union (purposely silent on the issue) and strongly favors state rights. Also, the north’s primary motivation was preservation of the union. Through the horror of the civil war, the cause expanded to include abolition of slavery. One final point, the politicians of the day deserve the strongest possible condemnation for allowing our country to dissolve into civil war with more than 600,000 fatalities. When has there been a greater failure of leadership/politics? I don’t fault Lincoln much for the fact we faced civil war, since he was nothing more than an ambitious and powerless Illinois politician during the events prior to his election. Once elected, he tried to mollify the South and then made the fateful decision to go to war rather than allow the South to secede. One could debate that decision, and it was an extraordinary fateful one, but Lincoln had to decide the issue and he had been elected to preserve the union.

> Are you going to be intelligent, or the typical liberal idiot and call me a racist?

Given that you’ve called me both a fool and an idiot, I really don’t see why you have any expectation that I should be civil to you, Mr. Thompson.

But no, I won’t call you a racist. I will say that your knowledge of the Steiner account is lacking. (For a start, his first name was Lewis, not Louis.) Steiner was not part of the “US Surgeon Generals of the Army of the Potomac,” but an inspector with the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a private organization founded to support U.S. troops during the war, not unlike the later American Red Cross.

I’ve discussed the limits of the Steiner account elsewhere, but it’s important to remember that Steiner was a civilian whose estimates and evaluation of bodies of troops may be less than fully reliable, at least compared to those of professional soldiers. While I don’t doubt Steiner was reporting what he saw as he understood it (an important caveat, always), his description of African American infantry formations in the Confederate Army isn’t corroborated by C.S. sources.

List those states rights. When you list them, use primary sources and show us how they were threatened by the federal government. If as you say, Lincoln supported the existence of slavery where it was and that the people of a state could decide if a state was to be free or slave, what state right was threatened?

The Constitution says nothing on permanence? The document itself reveals it to be permanent when examined as a whole. It was made open-ended so that it could be amended as needed. The intent of the people who created it and then later the body of the people in ratifying it understood it to be permanent. Go through the ratification conventions and see what was said about it. Even Patrick Henry remarked on its permanence.

It is the same argument that exists when secession gets brought up. Why put in something that was not meant to be? Secession was not contemplated by the Founders. The union of the states was to be permanent. They understood that no nation could survive if a part of it could enter and leave whenever they chose. Once in, always in.

Free blacks as confederate officers? Show some proof please.

@ Mr Hall,

First-Your reading comprehension is clearly lacking, as I did not call you an Idiot I only called you a fool. Therefore it is obvious you don’t understand at least half of what you read. 50% right is an “F-” even to the Yankees.

Second- I did not list my last name in any correspondence. SO, your use of it is clearly meant to intimidate. My rebel foot would be happy to kick your yankee ass.

Third- We all seem to find exactly what we are looking for when it comes to the war of northern aggression. You look for racism and that there could be NO way the war was fought over anything but slavery. I will believe my great great grandfather and not YOU or the people who got the privilege to write the history books.

@Jimmy,

Google it yourself

What you actually wrote was, “Are you going to be intelligent, or the typical liberal idiot and call me a racist?” Close enough.

No, not to intimidate. You don’t seem easily-intimidated, in any case. (Neither am I, by the way.) But I do think it’s important to note that I post under my actual name, while you choose to post insults anonymously. That’s one important distinction between you and me. Standing up for your Confederate heritage — or anything else — is pretty meaningless if you’re hiding behind a pseudonym.

Take a number. There are others in line ahead of you.

No one’s stopping you from writing a history book yourself. You have a choice — complain about the “privilege” of others who actually do the work, or step up and do a better job yourself.

Thanks for stopping by.

Why Google something when you can simply look it up in the primary source documents? Oh, that’s right. The only state’s rights mentioned where in connection with slavery. Take away the element of slavery and there were NO state rights being violated.

So we come right back to my challenge. List the state’s rights. Do not tell me to Google it because that only shows me you cannot list what does not exist.

So show me those state rights. Show me the primary sources explaining those state’s rights. If you cannot do that, then I would say my interpretation stands.

Oh, and use your real name.

Nice rhetorical question, you already know the answer to that, Dick.

The South seceded in large part due to the differences over slavery. However, just because the South seceded did not mean you have to have a war. The Civil War that followed was caused by the North’s desire to force the South back into the Union on its own terms. The North violated the sovereignty of the South by refusing to evacuate its army from Fort Sumpter and by repeatedly attempting hostile action to supply Fort Sumpter.

There is nothing in the constitution that prohibits secession. States entered the Union voluntarily and may exit in the same manner. The war that followed secession was caused by the North’s insistence on quashing state sovereignty and establishing ultimate Federal supremacy, using slavery as a convenient moral fig leaf for the effort, much the way the United States today uses “democracy” and associated “freedom rhetoric” to justify cynical military intervention around the world.

So, to recap, let’s get it straight: Slavery and the controversy surrounding it was a key cause of Southern secession. The decision of the South to exit the Union and start their own political entity caused the North to mobilize for war to force the South back into a Union the South did not wish to be a part of. Slavery caused secession and secession caused war. The destructive war was about SECESSION and STATE’S RIGHTS.

How do we know that the war was not about Slavery and the human rights of African slaves??

Because a few decades after the South was crushed and forced back into the Union and the true goals of the Civil War realized (the South forced back into the Union and fully subordinate to it), the North abandoned the freed slaves to Jim Crow and effectively a system of discriminatory apartheid and third class citizenship for almost 100 years, that was only mildly better than slavery for most. Things did not change for blacks until they decided to take to the streets and take their rights for themselves.

The Civil War was not fought for slavery. Slavery was a convenient moral excuse to mask a more cynical power struggle between the Southern States and the Federal government.correspondence that took place between Lord Acton and Robert E. Lee after the Civil War.

In that correspondence Lord Acton said,

“I saw in State Rights the only availing check upon the absolutism of the sovereign will, and secession filled me with hope, not as the destruction but as the redemption of Democracy. The institutions of your Republic have not exercised on the old world the salutary and liberating influence which ought to have belonged to them, by reason of those defects and abuses of principle which the Confederate Constitution was expressly and wisely calculated to remedy. I believed that the example of that great Reform would have blessed all the races of mankind by establishing true freedom purged of the native dangers and disorders of Republics. Therefore I deemed that you were fighting the battles of our liberty, our progress, and our civilization; and I mourn for the stake which was lost at Richmond more deeply than I rejoice over that which was saved at Waterloo.”

To which Lee answered,

“I yet believe that the maintenance of the rights and authority reserved to the states and to the people, not only essential to the adjustment and balance of the general system, but the safeguard to the continuance of a free government. I consider it as the chief source of stability to our political system, whereas the consolidation of the states into one vast republic, sure to be aggressive abroad and despotic at home, will be the certain precursor of that ruin which has overwhelmed all those that have preceded it.”

I know that States Rights has been smeared with the broad brush of racism; however, I reject that attempt to restrict the speech of a free people along with all of the strangulating impediments of political correctness.

America was designed to be a federal republic which operates on democratic principles. The continuing attempts to curtail the freedom of actions of the States and to transform the United States into a centrally-planned democracy run counter to our founding documents, our History, and, our nature.

Would you two be disappointed if the war wasn’t about slavery?

Most of your post appears to be copy-and-pasted from other, online sources, without attribution.

Why would the US need to abandon federal territory in the United States? You say the south had sovereignty. That is a joke. You then make a comment about secession that is a lie. States may not enter and leave the US at will. If you want to repeat the lie to feel good about it go right ahead, but you cannot find any evidence to support the lie. Instead, going to the ratification conventions we see plenty of evidence that rejects your lie including statements by Patrick Henry.

It looks like you have not uttered a primary source to support the idea that state’s rights caused the war. We see what you pasted which was uttered AFTER the war, not before it. If you want to see what was said before the war, go look up the secession conventions and what was said. Charles Dew’s Apostles of Disunion covers this as does William Freehling’s two books, Showdown in Virginia and Showdown in Georgia. http://www.amazon.com/Showdown-Virginia-1861-Convention-Union/dp/0813929644/ref=sr_1_9?ie=UTF8&qid=1431387569&sr=8-9&keywords=william+freehling and here http://www.amazon.com/Secession-Debated-Georgias-Showdown-1860/dp/0195079450/ref=sr_1_8?ie=UTF8&qid=1431387639&sr=8-8&keywords=william+freehling and Dew’s http://www.amazon.com/Apostles-Disunion-Southern-Secession-Commissioners/dp/081392104X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1431387676&sr=8-1&keywords=charles+Dew

Since the focus in on primary sources let us examine them like those historians did. What do the secession declarations tell us? That the seceding states were seceding over slavery.

You have not shown a specific state’s right that the federal government was violating.

As for who started the war, look no farther than Jefferson Davis ordering the attack on Ft. Sumter. He made a decision and it was morally and ethically wrong. When words were needed, Davis rejected their use and chose violence. The federal government did not mobilize for war until it was attacked by the forces of the CSA. The CSA mobilized for war prior to the attack on Ft. Sumter. It illegally seized US property. Adherents of the secessionists diverted arms and munitions to the CSA during the secession winter.

Federal armories were seized by the CSA as was the US Mint in New Orleans and its coinage and bullion. Those are all hostile acts which clearly placed the people who made those decisions and took those actions as traitors to the United States of America. You can yammer on all you want and lie until the cows come home, but the facts show the CSA as the instigator of the Civil War.

Ha ha ha I was googling for Dick. He doesn’t seem capable himself

Why Google when you know where the information is? http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/csapage.asp

The conversation here has drifted a little far afield from the monument at Arlington, so I’m going to close the comments for now and reopen them later.